Home » Information Technology

How did a hardworking nurse, Gerry, become a top social media influencer in the NHS?

Many of us take, of course, Top 10s with a pinch of salt!

Many of us have had chatted with Gerry about the NHS.

Gerry’s Twitter account is @archangelolill.

Gerry’s profile is self explanatory.

As a hardworking frontline nurse, Gerry’s views are very interesting.

One of the onrunning themes in this unique Twitter thread is how unfair it is for hardworking nurses, who don’t even get time to make a cup of tea as a break, get harpooned in the political discourse.

While people who have no clinical training, but have a management background, offer “advice” on compassion – and sell their ‘knowledge’ to the NHS – nurses like Gerry end up picking the pieces.

Gerry has often spoken about being demoralised through well rehearsed NHS scandals, which were very difficult for the nursing profession to cope with.

The hurt is that £20bn ‘efficiency savings’ are currently being delivered across all the main political parties. None of these ‘savings’ have been pumped back into frontline care, it is widely reported.

And many of these savings have been achieved by making draconian staff cuts, while balancing the budgets to negotiate crippling PFI loan repayments.

Now it turns out that Gerry is having the last laugh, in the face of her views about protecting the NHS which many find passionate.

Sometimes Gerry has been difficult to argue with, on grounds of the feelings whipped up, but Gerry freely admits this and means no offence at all it appears.

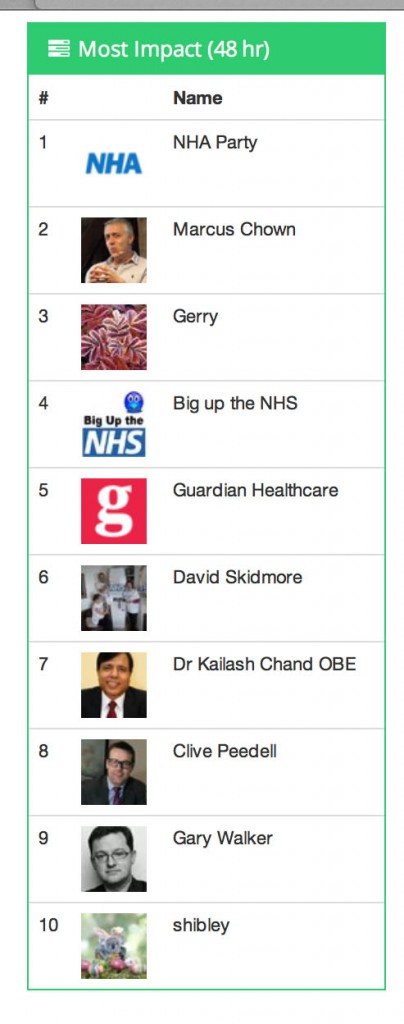

Gerry has recently come very high up in an impact poll published recently.

And guess who came last!

Should you give data altruistically, like you donate blood?

“Alongside what we have already done with the mandatory work programme and our tougher sanctions regime, this marks the end of the something-for-nothing culture,” Duncan Smith said in a conference speech for the Conservative Party last year.

The “something for nothing” meme, reinforced by the concept that “there is no such thing as society” (which Thatcher supporters vigorously claim now was ‘misunderstood’), remains a potent policy narrative.

The anguish which NHS England has experienced may be due to a fundamental problem with trust, as for example demonstrated elsewhere in reaction to GCHQ or NSA. But it could well be due to the “something for nothing” meme coming back to haunt the Government, which narked off public health specialists as the “opt out” has become unhelpfully enmeshed with concerns about commercial profiteering from health data.

“The Blood Donor” is a famous episode from the comedy series “Hancock”, the final BBC series featuring British comedian Tony Hancock. First transmitted on 23 June 1961, Anthony Hancock arrives at his local hospital to give blood. “It was either that or join the Young Conservatives”, he tells the nurse, before getting into an argument with her about whether British blood is superior to other types.

The issue of consent has predictably come to the fore, and it is generally felt that the communications strategy of NHS England over caredata went very badly wrong.

In an almost parallel universe, nothing to do with blood donations, it turns out that Labour is looking at bringing in a US-style system of allowing voters to register on election day amid growing fears that millions of people are about to drop off the official register in a “disaster for democracy”.

In a radical move, Labour is considering allowing same-day registration, which is credited with boosting turn-out from around 59% to 71% in some American states, according to the Demos think-tank. But the point is: mass paperwork involving the population at large is possible.

But now the issue has also become “there is no such thing as altruism”.

The Coalition announced in September 2013 that it had sold Plasma Resources UK to Bain Capital, the private equity firm. Plasma Resources UK (PRUK) turns plasma, the fluid in blood that holds white and red cellsin suspension, into life-saving treatments for immune deficiencies, neurological diseases and haemophilia.

The deal was hugely controversial, beyond typical disagreements over privatisation of national assets, because blood transfusions in the UK are voluntary; if donors think that someone is going to make a profit from their donation, they may well not give blood at all.

Richard M. Titmuss was a professor of social administration at the London School of Economics form 1950 until his death in 1973. He had an international reputation as an uncompromising analyst of contemporary social policy and as an expert on the welfare state.

Richard M. Titmuss’s “The Gift Relationship” (recently edited by Ann Oakley and John Ashton) has long been acknowledged as one of the classic texts on social policy.

A seemingly straightforward comparative study of blood donating in the United States and Britain, the book elegantly raises profound economic, political, and philosophical questions. Titmuss contrasts the British system of reliance on voluntary donors to the American one in which the blood supply is largely in the hands of for-profit enterprises and shows how a nonmarket system based on altruism is more effective than one that treats human blood as another commodity.

His concerns focused especially on issues of social justice. The book was influential and, indeed, resulted in legislation in the United States to regulate the private market in blood.

But shouldn’t you simply donate data ‘for the public good’, in the same way you can choose to donate blood?

The start of a new data sharing scheme involving the pseudonymised medical records of those who do not opt out will be postponed to give patients more time to learn about its benefits and safeguards, NHS England has announced.

Part of the semantics of the legal data involves whether a discussion of the giving of data is ultimately separable from the discussion of the purposes for which these data are ultimately applied.

HSCIC, Health Statistics Collaboration with Insurance Companies, reported on its insurance collaboration intentions last August. Section 2.3.1 of its Information Governance Assessment Addendum stated their intentions very clearly, as Roy Lilley earlier pointed out.

“There is no legal requirement to differentiate between the release of data to NHS commissioners and any other potential data recipient. In the eyes of the law, a government department, a university researcher, a pharmaceutical company, or an insurance company is as entitled to request and receive de-identified data for limited access as a clinical commissioning group, as long as the risk that a person will be re- identified from the data is very low or negligible.”

“Furthermore, all such organisations can make good use of the data. Access to such data can stimulate ground-breaking research, generate employment in the nation’s biotechnology industry, and enable insurance companies to accurately calculate actuarial risk so as to offer fair premiums to its customers.”

The Centre for the Study of Incentives in Health in London is a cluster of academics looking at the pros and cons of whether incentives can influence behaviour.

The issue of paying individuals to change their behaviours in health-enhancing ways, for example by encouraging them to quit smoking or take regular exercise, is a highly topical policy issue, in the UK and internationally. Yet personal financial incentives are potentially riddled with legal ethical issues, with concerns regarding their precise effectiveness, and with further concerns that they may have unintended consequences.

Paying people to undertake particular actions may crowd out their intrinsic motivations for wanting to do those actions, as demonstrated by Richard Titmuss’ classic work on blood donations almost forty years ago

Arguably, a final nail in the coffin came from a report by Randeep Ramesh that drug and insurance companies might be able to, from later this year, buy information on patients – including mental health conditions and diseases such as cancer, as well as smoking and drinking habits – once a single English database of medical data has been created.

However, advocates argued that sharing data will make medical advances easier and ultimately save lives because it will allow researchers to investigate drug side effects or the performance of hospital surgical units by tracking the impact on patients.

Possibly, now is an opportune time to revisit Richard Titmuss’ thesis.

One can only speculate what he would have made of the current furore over ‘caredata’. I suspect though he would care.

The Right needs to make up its mind: is society, or the individual, more important?

Socialism has never been clearer.

We not consider the State to be a ‘swear word’. We are proud of our values of solidarity, social justice, equality, equity, co-operation, reciprocity, and so it goes on.

The Right, meanwhile, needs to make up its mind: is “societal benefit” more important, or the individual?

The rhetoric under Margaret Thatcher and beyond, including Tony Blair, was individual choice and control could ‘empower’ individuals. This was more important than the paternalistic state making decisions on your behalf, and indeed Ed Miliband was keen to read from the same script at the Hugo Young lecture 2014 the other week.

Yet, the phrase “societal good” has been used by an increasingly desperate Right, wishing to justify money making opportunities in caredata, or cost saving measures such as NICE medication approvals or hospital reconfigurations, So where has this individual power gone?

Whilst fiercely disputed now, Thatcher’s idea that ‘there is no such thing as society’ potentially produces a sharp dividing line between the rights of the individual and the value of society.

“There is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women, and there are families. And no government can do anything except through people, and people must look after themselves first. It is our duty to look after ourselves and then to look after our neighbour.

was an individualist in the sense that individuals are ultimately accountable for their actions and must behave like it. But I always refused to accept that there was some kind of conflict between this kind of individualism and social responsibility. I was reinforced in this view by the writings of conservative thinkers in the United States on the growth of an `underclass’ and the development of a dependency culture. If irresponsible behaviour does not involve penalty of some kind, irresponsibility will for a large number of people become the norm. More important still, the attitudes may be passed on to their children, setting them off in the wrong direction.”

(M. Thatcher, Woman’s Own, October 31, 1987)

Whilst the Left has been demonised for promoting a lethargic large State, monolithic and unresponsive, there’s been a growing hostility to large monolithic private sector companies carrying out the State’s functions.

It is alleged that some of these companies are not doing a particularly good job, either.

It has recently been alleged that the French firm, ATOS, judged 158,300 benefit claimants were capable of holding down a job – only for the Department of Work and Pensions to reverse the decision. At the end of last year, private security giants G4S and Serco have been stripped of all responsibilities for electronically tagging criminals in the wake of allegations that the firms overcharged taxpayers

So why should the Right be so keen suddenly on arguments based on ‘societal benefit’?

It possibly is a cultural thing.

The idea that “large is inefficient” was never borne out by the doctrine of ‘economies of scale’, which is used to justify the streamlining of operational processes across jurisdictions for multinational companies.

This was a naked inconsistency with the excitement in corporate circles with “Big Data”, that big is best.

Many medical researchers are rightly excited at the prospect of all this data. Analysis of NHS patient records first revealed the dangers of thalidomide and helped track the impact of the smoking ban. This new era of socialised big NHS data could be very powerful indeed. Whilst there were clearly issues with informed consent at an individual level, the argument for pooling of data for public health reasons were always compelling.

The fact that this Government is simply not trusted when it comes to corporate capture has strongly undermined its case. Also, if the individual must put itself first, why should he allow his data to be given up? Critically, this knowledge doesn’t just have a social good, or multiple individual health ones. It has economic value too.

It might simply be that the Right is keen on this policy through now is precisely because such data will offer significant financial benefits, and that any to wellbeing are simply pleasant side-effects. The concern that this policy is actually about boosting the UK life sciences industry, not patient care. This is science policy – where science lies within the technical jurisdiction of the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills – not just health policy.

Is it not reasonable that an individual should have the right to opt out of having his caredata being absorbed?

“Societal good” has been used by the current Government in a different context too.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) will consult next month on an update to its methodology for assessing drugs. It had been asked by the Department of Health to make judgments on the “wider societal benefit” of medicines before recommending them for NHS use. But a board meeting this week has decided it would be wrong to make an assessment that effectively would put a monetary value on the contribution to society of the people likely to be taking the drugs.

It is thought that any assessment of “wider societal benefit” would inevitably end up taking age into account, say papers from the meeting. “Wider societal benefit” could therefore be simply an excuse for excluding more costly older patients.

NICE’s chief executive, Sir Andrew Dillon, has said it is valid to take into account the benefit to society of a new drug, but great care had to be taken in the way it was done, so that an 85-year-old was not regarded as less important than a 25-year-old. One group of patients should never be compared with another.

But an older individual must put his access to medications first surely?

A legal challenge brought by the local authority and the Save Lewisham hospital campaign showed conclusively that the secretary of state did not have the power to include Lewisham in a solution to the problems of SLHT.

As Caroline Molloy explains:

“The hospital closure clause gives Trust Special Administrators greater powers including the power to make changes in neighbouring trusts without consultation. It was added to the Care Bill just as the government was being defeated by Lewisham Hospital campaigners, in an attempt to ensure that campaigners could not challenge such closure plans in the future. But the new Bill could be applied anywhere in the country.”

Clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), the groups of state representatives making local health plans about resource allocations, will still need to be consulted in this process, and the consultation has been extended to 40 days. However, disagreements between CCGs may now be overruled by NHS England. So, the most important local decision makers may have no say in key reconfigurations of their hospitals and care services.

An individual within a locality must surely have the right to put his own interests regarding social provision first?

I believe that part of the reason the Right has got into so much trouble with caredata, access to drugs and clause 118 is that it appears in fact to ride roughshod over people’s individual rights, and in all three cases is only considering the potential economic benefit to the budget as a whole. They are not interested in the power of the individual at all.

And the most useful explanation now is actually that with such overwhelming corporate capture engulfing all the main political parties, that there’s no such thing as “Left” and “Right” any more. It might have been once our duty to look after ourselves, but it is clear that conflicts have emerged between individual autonomy and the needs of the corporates.

The “Right” is not actually working for the needs of the individual at all, nor of society.

The most parsimonious reason is that the Right is not as such a Right at at all. It, under the subterfuge of being “centre-left” or “centre right”, is simply acting for the needs of the corporates, explaining clearly why so many are disenfranchised from politics. From this level of performance, the Right has not only failed to safeguard the interests of the Society, it has failed to uphold the rights of the individual. This is an utter disgrace, but entirely to be expected if the Government governs on behalf of the few.

Of course we knew that this would happen under the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats, but Labour needs to return to democratic socialism urgently.

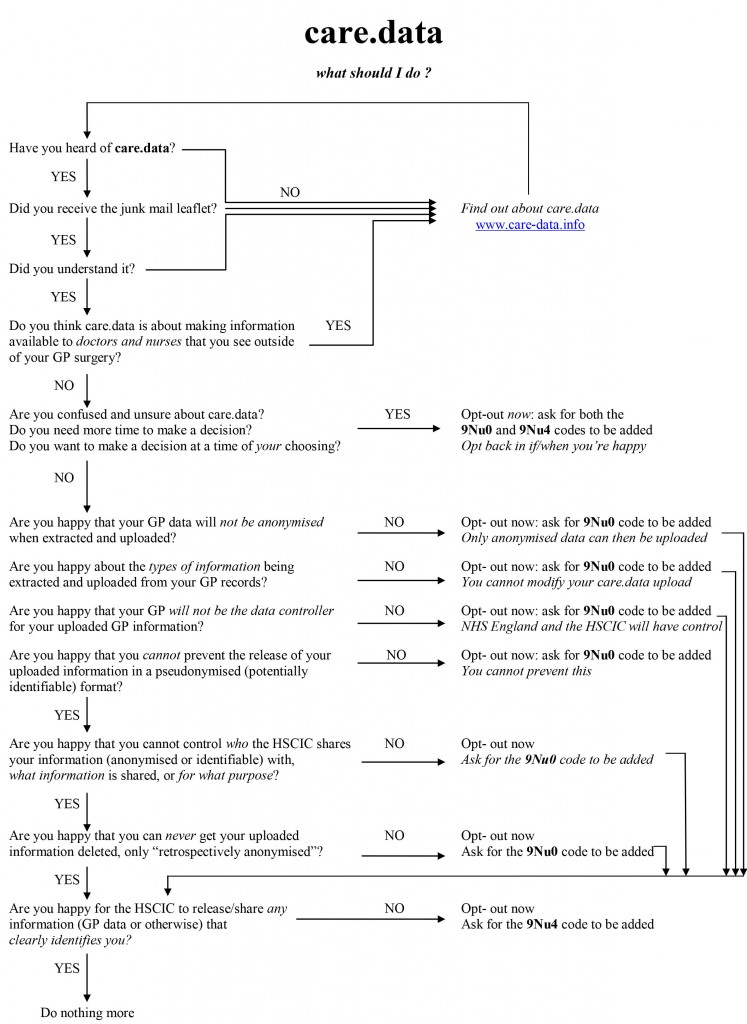

Dr Neil Bhatia’s #CareData flow chart

This is Dr Neil Bhatia on Twitter here, @docneilb.

Feel free to contact him over opting out from #CareData.

Here Phil Booth (@MedConfidential) campaigner battling against erosion of valid consent, so essential plank for the medical profession, and Tim Kelsey (@TKelsey1), a guru in big data for the NHS, battle it out.

Flow chart

The sting in NHS data sharing is in making insurance contracts void

Even Google gave up on their central database for health information called “Google Health“. Whilst few things are as certain as death and taxes, it is fairly certain that there is big money in big data. Lord Shutt of Greetland, Chair of the Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust Ltd. warned, in a foreword on a recent report on “the database state“, that the problem is huge, and as a society we must face up to formidable challenges. There has always been a tough balance in the law between balancing individual rights of privacy and freedom, with the State’s rights of national policy of health and security, for example. Whatever ideological position the Liberal Democrats eventually settle on, it is striking that a Conservative Prime Minister should actually advocate nationalising something.

It is unsurprising that Big Pharma would have welcomed the move. Andrew Witty, the chief executive of GlaxoSmithKline, stated to the Sunday Telegraph he welcomed the data-sharing initiative: “Any action the government takes to improve the environment in this country for life science across these activities is welcome.” The Autumn Statement (2011) had indeed signposted this. It might seem paradoxical that the Department of Health at this time wishes to embark on an initiative to make the NHS “paperless”, at a time when a reorganisation, estimated at £3bn, is currently underway. Patient data, essential for individual patient security, confidentiality and consent, are “rich pickings” for the private healthcare industry, which have not collectively paid to collect this information nor invest in the IT infrastructure of the NHS, but the ethical concerns are enormous. Personalised medicine, dependent on real-time patient information, is “the next big thing” emergency in the pharmaceutical industry, currently keeping stocks of companies very healthy. However, the professional code for Doctors, from the General Medical Council (“GMC”) is very clear on the regulation of patient confidentiality and privacy: this is contained within “Confidentiality” (2009), and clearly guides doctors on the conflicting balance between confidentiality and disclosure.

There are interesting reasons why the operational roll-out of the National Patient Record failed in 2006-7. It is now reported that all prescriptions, diagnoses, operations and test results will be uploaded on to central computers by the end of next year, and, by 2018, all NHS organisations will be expected to be able to share this information with other hospitals, GPs, ambulances and health trusts. Jeremy Hunt hopes local councils will sign up to similar systems, along with private care homes. As with the overall direction of travel of the NHS towards an insurance system where private companies pay “a greater part”, this blurring of the need for patient consent has been insidious.

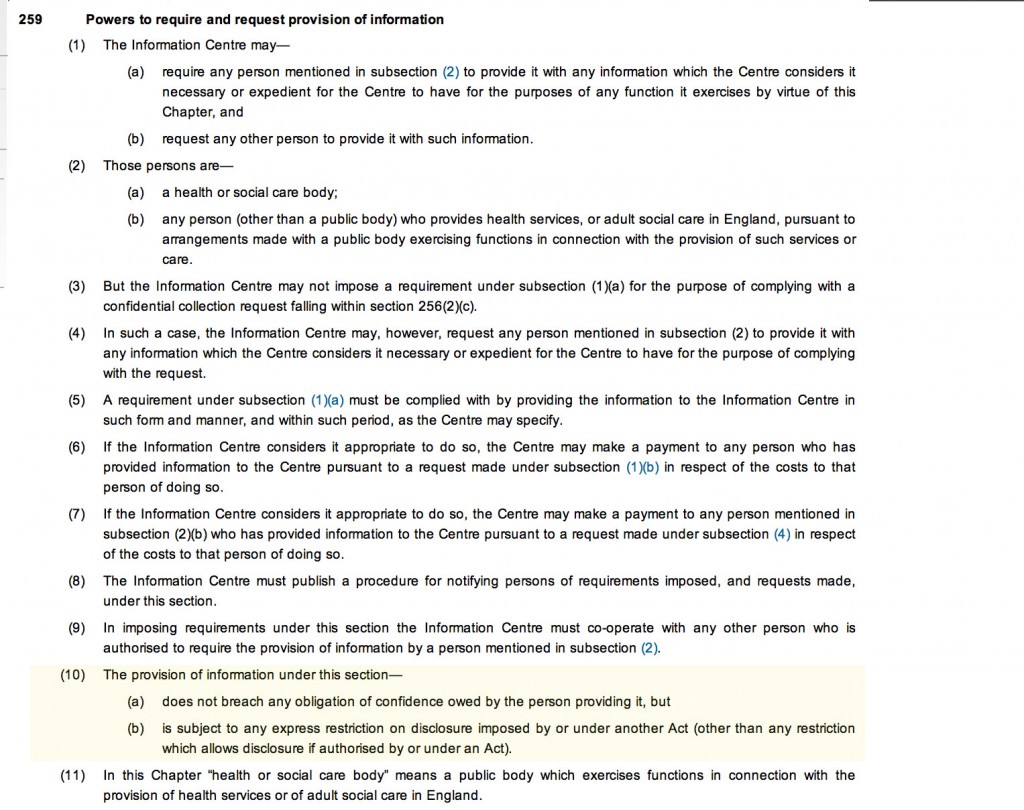

Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006 (originally enacted under Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 2001), allows the common law duty of confidentiality to be set aside in specific circumstances where anonymised information is not sufficient and where patient consent is not practicable. For example a research study may require access to patient identifiable data to allow linkages between different datasets where the cohort is too large for consent. This would require time limited access to identifiable information where gaining consent from a large retrospective cohort would not be feasible and would require more identifiable data than would be necessary for linkage purposes. However, section 10 of the Data Protection Act (1988) currently allows a right for an individual to prevent damage or distress by data processing. This is indeed conveniently “triggered” by section 259(10) of the Health and Social Care Act (2010), i.e. “[the provision] is subject to any express restriction on disclosure imposed by or under another Act (other than any restriction which allows disclosure if authorised by or under an Act”:

The Secondary Uses Service (SUS) Programme supports the NHS and its partners by providing a single source of comprehensive data for planning, commissioning, management, research, audit, public health and “payment-by-results”, a reimbursement mechanism for acute care payments. It is critical to know whether patients maintain a right to opt out of the SUS database. It should not be the case that NHS patients are denied hospital care if they do not agree to my records being sent to SUS. Steve Nowottny in his “Editor’s Blog” for Pulse, a newspaper circulated to GPs, on 8 January 2013 outlined some important very recent developments:

“That year, Pulse ran a ‘Common Sense on IT’ campaign which highlighted a series of concerns over the consent and confidentiality safeguards in the new system.

“GPs wanted patients to have to give explicit rather than merely implied consent before records were created. Plans to use data within the records for research purposes without explicit consent had Catholic and Muslim leaders up in arms, because they feared the research could be purposes contrary to their faiths, such as abortion or stem cell research.

We revealed that celebrities, politicians and other patients whose information is regarded as sensitive would be exempted from the automatic creation of a Summary Care Record, raising questions about the system’s security. And we reported that patients who did not initially choose to opt out of the Summary Care Record would be unable to have their records subsequently deleted.

At the time, it felt as though the stories, while interesting and concerning, were somewhat theoretical. The Summary Care Record’s deployment to date had been patchy and it was far from certain it would continue. In the meantime, fewer than 1% of patients had bothered to opt out. (Now, with nearly 22 million records created and more than 41 million patients contacted, the figure stands at 1.34%).

But the news today that 4,201 patients had Summary Care Records created without them giving even implied consent – and that they will not be able to have them deleted – reignites the whole debate. Suddenly ‘what if’ scenarios have become reality.”

Tim Kelsey is the NCB’s National Director for Patients and Information – his stated aims are to put transparency and public participation at the centre of a transformation of customer service in the NHS. In a recent lecture, he quoted George Soros who said “our social institutions are imperfect, they should be open to improvement [and that] requires transparency and data“. On-line banking and e-ticketing demonstrate the power of open access to personal data in a safe, secure way – for some reason, heath data is deemed more personal that finance and travel arrangements. Data.gov.uk is an example of his vision for the future – the UK has so much medical data, not only about patients but also genomics and other bioinformatics disciplines. The law currently gives the NCB power to mandate more data flows – Kelsey apparently targets April 2014 to get outcomes-based data flows from primary and secondary care – once achieved, next step is to embrace social and specialist care. So, once the data is “freely available”, it can be made available for public participation – he is investing in a course called ‘Code for Health’, a 3 day course to learn how to develop apps. Data are essential from April 2013, there will be push for on-line interaction with GPs, to realise nationally the benefits seen in pilot areas.

So why should commissioners need access to “personal identifiable data”? It is considered that these may be “good reasons”:

- integrated care and monitoring services including outcomes and experience requires linkages across sources

- commissioning the right services for the right people requires the validation that patients belong to CCGs and have received the correct treatments

- aspects of service planning and monitoring on geographic data basis require postcodes for certain type of analysis

- understanding population and monitoring inequalities

- target support for patients and population groups at highest risk requires data from several sources linked together

- specialist commissioning is commissioned outside local areas and can require wider discussions about individual patients and their associated costs

- ensuring appropriate clinical service delivery and process requires access to records

To enable commissioning, ‘personal identifiable data’ including NHS no, DOB, Postcode data needs to flow to “data management integration centres” (“DMICs”). The DMICs need to have similar powers and controls to the Health and Social Care Act information centres to process data It was known that, in order for processing of PID at DMICs to be undertaken legally, a change in legislation would have been required.

David Cameron has stated explicitly his intention for social care to head towards a private insurance system. As stated in the transcript of the interview with Andrew Marr,

“Well the point that was being made earlier on the sofa by Nick Watt, this is a massive problem – that you know more and more people suffering from dementia and other conditions where they go into long-term care and there are catastrophic costs that lead them to have to sell their homes to pay for that care – it’s right to try and put in place a cap which will then open up an enormous insurance market, so people can insure against that sort of catastrophic loss.”

A longrunning conundrum about where there is such intense interest in ‘raising awareness of dementia’. The idea of having GPs and physicians ‘diagnose’ dementia on the basis of a screening test, without it being called ‘screening’ in name, has not been backed up with the appropriate resource allocation for dementia care elsewhere in the system, including adequate training for junior doctors and nurses crucially involved in actual dementia care. Is this and integration of care an entirely virtuous sociological problem? Integration of care at first sight seems to involve primarily avoidance of reduplication of operations, and better ‘coordinated’ care between health and social care and funding. This is not an unworthy ambition at all. It is well known that the endpoint of the Pirie and Butler “Health of Nations” blueprint for NHS privatisation has a greater rôle for the private insurance market as the endpoint, so it makes complete sense to have a fully integrated IT system which private insurers and the Big Pharma can tap into.

Lawyers will, of course, be cognisant about the added beauty of integration of clinical and financial information. One of the biggest banes of insurance markets is information asymmetry, making calculation of risk and potential payouts difficult. Insurers will argue that calculation of risk is only possible with precise information, clinical commissioning groups are merely “statutory insurance schemes”. It is a long-held belief that private insurers refuse to pay off given the slightest lack of compliance in terms and conditions, but private insurers provide that this mechanism needs to exist to protect them making unnecessary payouts. Failure to disclose medical conditions is an excellent way for private insurers to get out of “paying up”, otherwise known as rescission. Of course, this could be taking the “conspiracy theory” far too far, and these concerns about the use of “big data” otherwise than for a “public good” may be totally unfounded.

You can, nonetheless, mount an argument why the current Government wish to progress with this particular approach to private medical data. The private insurance market and Big Pharma stand to benefit massively, and their lobbying is much more sophisticated than lobbying from GPs, physicians or members of the public. The drive towards all nurses having #ipad3s and all TTOs from Foundation Doctors being sent by broadband to nursing homes may seem utterly virtuous, but there are more significant drivers to this agenda beyond reasonable doubt. On the other hand, it’s simply that healthcare policy is in fact improving for the benefit of patients.

Extremely grateful to the work of Prof Ross Anderson, Chair of Computer Security at Cambridge University, and Phil Booth @EinsteinsAttic on Twitter with whom I have had many rewarding and insightful Twitter conversations with @helliewm.

Are we actually promoting the NHS ‘choice and control’ with the current caredata arrangements?

In the latest ‘Political Party’ podcast by Matt Forde, an audience member suggests to Stella Creasy MP that wearing a burkha is oppressive and should not be condoned in progressive politics. Stella argued the case that she can see little more progressive than allowing a person to wear what he or she wants.

The motives for why people might wish to ‘opt out’ are varied, but dominant amongst them is a general rejection of commercial companies profiteering about medical data without strict consent. This is not a flippant argument, and even Prof Brian Jarman has indicated to me that he prefers a ‘opt in’ system:

Patients are not fully informed about how their information will be used. For such confidential data they should have to opt in @legalaware

— BrianJarman (@Jarmann) January 28, 2014

If people are properly told the pros and cons they can decide if they want to accept the cons, for the sake of the pros @sib313 @legalaware

— BrianJarman (@Jarmann) January 27, 2014

There are potential benefits, but also risks and if the risks happen they’re irreversible. Hence it’s safer to have opt-in. @legalaware

— BrianJarman (@Jarmann) January 27, 2014

Opting out can be argued as not being overtly political, though – it is protecting your medical confidentiality. People may (also) have political reasons for doing this, but the choice is fundamentally one about your right to a private family life. The government (SoS) has accepted this, and that is why it is your NHS Constitution-al right to opt out – you don’t have to justify it and if you instruct your GP to do it for you, she must.

It’s argued fairly reliably that section 251 of the NHS Act 2006 maps exactly onto Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 2001. Section 60 was implemented the following year under Statutory Instrument 2002/1438 The Health Service (Control of Patient Information) Regulations 2002. It is argued that the Health and Social Care Act 2012 did not modify or repeal those provisions of the HSC Act 2001 or the NHS Act 2006, nor did it modify or repeal any related provision of the Data Protection Act 1998. SI 2002/1438 remains in force. However, noteworthy incidents did occur under this prior legislation, see for example this:

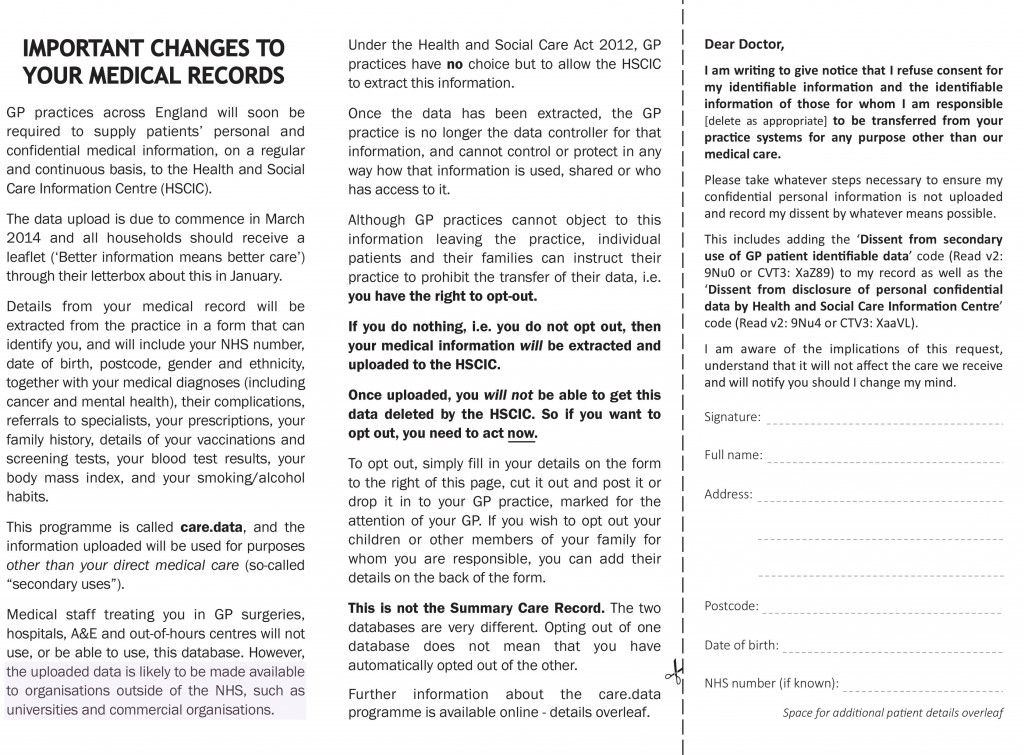

Whatever motive you have for arguing against care.data, whether the whole principle of it, the HSCA removing any requirement for consent, the fact that it is identifiable data being uploaded from GP records (i.e. not anonymised or pseudonymised), or that the data will be made available, under section 251, for both research and non-research purposes, to organisations outside of the NHS, etc, the matter remains that the is no control over your data unless you opt-out.

Proponents of the ‘opt out’ therefore propose their two lines of action: either prevent your identifiable data being uploaded (9Nu0) and so effect a block on the release of linked anonymised or pseudonymised (potentially identifiable) data, which otherwise you cannot prevent or control; or block all section 251 releases (9Nu4), whether or not you apply the 9Nu0 code.

The point is, they argue, that you – the patient – cannot pick and choose, when, to whom, or for what purposes your data will be released. You cannot prohibit your data from being released for purposes other than research, or to organisations out with the NHS. This is completely at odds to the ‘choice and control’ agenda so massively advanced in the rest of the NHS. While it has been argued that the arguments against commercial exploitation of these data should have been made clearer beforehand, it’s possibly a case ‘I know we’re going there, but I wouldn’t start from here.’

Compelling arguments have been presented for the collection of population data. It’s argued wee need population data to do prevention and to monitor equity of access and use. It’s an open secret that the current Government is continuing along the track of privatising the NHS; arguably making it all the more important to have good data so we know what is happening. Having more of this data at all starting in the private sector, under this line of argument, is much less transparent, as it’s hidden from freedom of information from the start.

It’s, however, been argued that “the route to data access” has in fact changed. Under Health and Social Care Act (2012), it was intended that either the Secretary of State (SoS) or NHS England (NHSE) could direct HSCIC to make a new database, and – if directed by SoS or NHSE – HSCIC can require GPs (or other care service providers) to upload the data they hold. care.data represents the single largest grab of GP-held patient data in the history of the NHS; the creation of a centralised repository of patient data that has until now (except in specific circumstances, for specific purposes) been under the data controllership of the people with the most direct and continuous trusted relationship with patients. Their GP.

HSCIC is an Executive Non Departmental Public Body (ENDPB) set up under HSCA 2012 in April 2013. NHS England, the re-named NHS Commissioning Board, was established on 1 October 2012 as an executive non-departmental public body under HSCA 2012. Therefore, to suggest that the government has ‘little control’ over these arm’s-length bodies is being somewhat flimsy in argument – they were both established and mandated to implement government strategy and re-structure the NHS. There are also problems with the “greater good” argument; being paternalistic, the opposition to caredata spread bears similarity to the successful opposition to ID cards. This argument presumes that patients will benefit individually, when – and it ignores the fact that it is neither necessary or proportionate –and may be unlawful under HRA/ECHR – to take a person’s most sensitive and private information without (a) asking their permission first, and (b) telling them what it will be used for, and by who. Nobody is above the law, critically.

The fact is that the data gathered may increment the data available to research but that in its current form, care.data may actually not be that useful – it includes no historical data, for starters. And all this of course ignores the fact that care.data (and the CES that is derived from linking it to HES, etc.) will be used for things other than research, by people and companies other than researchers. That is the linchpin of the criticism. Finally, the Care Bill 2013-14 – just about to leave Committee in the Commons – will amend Section 251, moving responsibility for confidentiality from a Minister (tweets by Ben Goldacre here and here).

Anyway, the implementation of this has been completely chaotic, as I described briefly here on this Socialist Health Association blog. What now happens is anyone’s guess.

The author should like to thank Prof Ross Anderson, Chair of Security Engineering at the Computer Laboratory of the University of Cambridge, Phil Booth and Dr Neil Bhatia for help with this article.

Sledgehammers and nuts: opt-outs and data sharing concerns for the NHS?

You couldn’t make it up.

“a substantial number of GPs are so uneasy about NHS England’s plans to share patient data that they intend to opt their own records out of the care.data scheme.”

“The survey of nearly 400 GP respondents conducted this week found the profession split over whether to support the care.data scheme, with 41% saying they intend to opt-out, 43% saying they would not opt-out and 16% undecided.”

Simon Enright, Director of Communications for NHS England, tweeted to indicate methodological issues with concluding too much from this ‘snapshot survey':

@legalaware disappointing that Pulse did self-selecting sample with potential question bias in survey.

— simonenright (@simonenright) January 26, 2014

And of course Simon Enright is right. But one has to wonder how much GPs themselves have been informed about the debate about data sharing concerns. GPs are trained to explore, and in fact examined on exploring, the ‘beliefs, concerns and expectations’ of their patients; so it would be unbelievable to assume that no one had had this particular conversation with a patient.

GPs tend to be a very knowledgeable and versatile group of medical professionals, and indeed many have an active interest in public health.

But here there’s been another problem at play? All of the patients who I know, because of the known issues in waiting for an appointment to see their GP for ‘routine matters’, have decided to opt-out by simply dropping in to sign a form with the receptionist. But that sample could even be more unreliable than the Pulse survey.

For all of the huge budget that’s set aside for NHS England’s interminable activities on patient engagement in the social media and beyond, you’d have thought a spend on explaining data sharing would’ve been money well spent?

Views on an individual’s right to ‘opt out’, described in a previous blogpost of mine, vary.

There are many good arguments for proposing the sharing of care data, but the lack of willingness of industry, primary care or public health to discuss openly how data sharing might be necessary and proportionate, under the legal doctrine of proportionality, is utterly bewildering.

What has resulted is an almighty mess.

In as much as there is a ‘root cause’ of this problem, an unwillingness to make the arguments for data sharing with the general public is a good candidate.

Julie Hotchkiss, a public health physician, has for example written to Tim Kelsey about the matter today.

Dear Mr Kelsey

re:Care.data

I think there is so much to be gained by collation of personal health data – for epidemiological observation (prevalence, time trends, variation), allowing data-linkage enjoyed by other countries such as Sweden, to aid commissioning of health services as well as, of course, for direct patient care. For all these reasons I support in principle the care.data initiative. However I have grave concerns about how the data might be used. I am aware that many, many people share these concerns, and many of these have been expressed in the press in recent weeks. Many of my colleagues (long term NHS employees) are saying they will opt out. There are a number of senior voices in the Public Health world who are urging people to opt out.

NHS England is in a unique place to be able to address these concerns – but in many ways the horse has bolted, and I fear we may never get it back in the stable. PLEASE now put your energies and resources into a full and frank consultation, including IT experts, medical colleges, academia and for goodness sake – the general public! The fact that no such awareness raising and consultation has taken place makes people suspicious. They already don’t blindly trust the NHS / government anymore. So if you want to get health professionals and academics behind you in order to have a greater number of voices advocating for care.data please address the following concerns – in a published document- as soon as possible.

- definitive ownership of the data

- responsibility for data quality

- assurance (ideally in legislation) that ownership or data management will remain with a governmental agency and not be out-sourced

- will the HSC IC own the data, and allow access through a form of brokerage (allowing specific views/queries) or access to the full data set)?

- detailed Information Governance arrangements, e.g. requirements for Section 251 approval?

- what Research Governance / Ethical approval arrangements are being put in place?

- what will organisations have to pay,? and if so is this a handling fee or will they get ownership of the data?

- criteria for granting access to data and legally binding restrictions on usage of the data

- exactly to what extent will records be identifiable (for instance the long-established practice at ONS of suppressing cells with fewer than 5 individuals from disclosure)

Although I expect a response, more than this I expect published documents to detail all these issues. I’m sure there are many other details specialists in health research, Information Governance, medico-legal matters and civil libertarians would require in order to be assured that this was something in which they could participate.

Kind regards

Julie Hotchkiss, Fellow of the Faculty of Public Health

Another question for Tim Kelsey may be, potentially, whether the data from care.data will be processed according to the National Statistics Code of Practice.

It is somewhat unclear why the public health community have not had themselves a discussion with the general public, despite some advocates of this community now complaining very loudly about the presentation of ideas leading to the ‘opt out campaign’.

But they will need to confront the stench of public mistrust aimed at various politicians. Examples of events leading to this profound distrust include the NSA/Snowden affair, and relevations at GCHQ.

The corporate capture in some areas of public health is not a topic which public health physicians have wished to talk about. However, these authors somehow managed to sneak an excellent discussion of the phenomenon here in the British Medical Journal.

There have been calls for much tighter regulation of “data brokers”, as corporates wish to rent-seek this plethora of data. What always appeared to have been lacking was an “intelligent debate” with the general public about data sharing. Nonetheless, the social media, for example “Open democracy: our NHS” websites, have for a very long time been publishing relevant articles on this subject.

There was also the small issue of how the £3bn implementation of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) came into being, which led to a turbo-boost of the outsourcing and privatisation of the NHS. Members of the academic public health community were slow on the uptake there too – some would say “completely asleep on the job”, perhaps not as far as their own research interests are concerned, but on the specific issue of potential violation of valid consent for individuals.

And guess what the Health and Social Care Act (2012) also contains a legal ‘booby trap’, which many did not see fit merited discussion with the general public.

Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006 (originally enacted under Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 2001), allows the common law duty of confidentiality to be set aside in specific circumstances where anonymised information is not sufficient and where patient consent is not practicable. For example a research study may require access to patient identifiable data to allow linkages between different datasets where the cohort is too large for consent.

This would require time limited access to identifiable information where gaining consent from a large retrospective cohort would not be feasible and would require more identifiable data than would be necessary for linkage purposes. However, section 10 of the Data Protection Act (1988) currently allows a right for an individual to prevent damage or distress by data processing.

This is indeed conveniently “triggered” by section 259(10) of the Health and Social Care Act (2010), i.e. “[the provision] is subject to any express restriction on disclosure imposed by or under another Act (other than any restriction which allows disclosure if authorised by or under an Act”:

The trust is further eroded through the loss of data from government agencies, coherently tabulated on this Wikipedia page.

Proponents of democratic socialism have long argued that citizens often are not able to buy influence through competing with large corporates, but can legitimately exert influence through the ballot box.

There is also no doubt that people are talking at cross-purposes. There is a bona fide case for disease registries and surveillance, for example. However, the problems of an individual’s data being shared with lack of informed valid consent in the name of population presumed consent do need to be addressed ethically at least.

Public health physicians who would like to see the law applied to promote public health and research overall cannot condone profiteering from personal data abuses. Tim Kelsey has always been adamant that the English law is strong enough to cope with such threats. The scenario has mooted before of private insurance companies being able to abort insurance contracts (rescission) from data disclosed to them, on the grounds of misrepresentation or non-disclosure, but the position of the NHS England has always been to present such scenarios as far-fetched.

However, the issues appear to have been intelligently debated at European level. The draft “EU General Data Protection Regulation on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data” (the EU Regulation), was published in 25 January 2012, and has been debated in the European Parliament for most of the time since then.

Under “Albrecht’s proposals“, health data should generally only be able to be processed for the purposes of historical, statistical or scientific research where individuals have consented to such processing. It would be legitimate for processing in the context of research to take place without consent only where: (a) the research would serve an “exceptionally high public interest”; (b) the research involves anonymous data from which individuals could not be re-identified; and (c) the regulators have given their prior approval. Consent, however, is to follow the stricter interpretation, requiring explicit, freely given, specific and informed consent obtained through a statement or “clear affirmative action”. There is, however, legitimate concerns that these proposals might damage the interests of both corporate and public health communities.

It looks very much like chaos has set in since 2010 in running the NHS. Any party can do better than this.

This is of course an almighty mess, and it is hard to know how the whole thing could have been approached better. A plethora of issues have converged seemingly at once, and there is a possibility a ‘big opt out’ would still deliver a result without the matters having been properly discussed. If you think this is bad, consider what would happen in a national discussion of the terms of our membership of the European Union?

by @legalaware

Cameron’s #CostofNHSConfidentialityCrisis

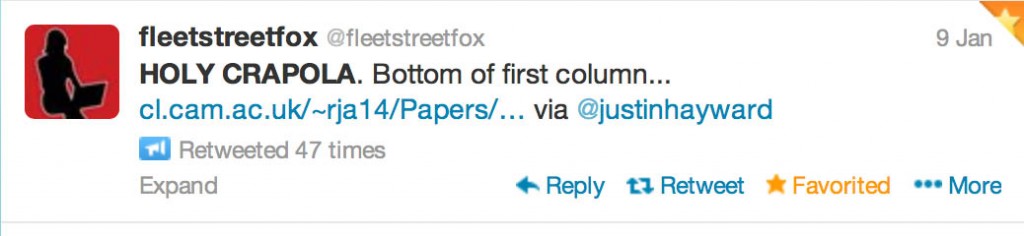

Thanks to @fleetstreetfox for tweeting this last night.

And THIS tweet refers to THAT sentence (see bottom of the first column):

You have just eight weeks to opt out of having your and your family’s confidential medical information uploaded from your GP’s systems, then passed on or sold to others – including private companies.

For more information, see www.medconfidential.org where you can download an opt out form, should you wish to opt out.

And please do pass these links on:

www.medconfidential.org/how-to-opt-out

for a copy of the form and a letter for you to use, if you prefer

www.care-data.info for detailed information on the care.data programme by the GP who wrote the content of the opt out form

for a direct link to a PDF of the form for use on Twitter, etc.

Keep safe.

Is technology a friend of the NHS?

Imagine if you could 3-D print a pink diamond.

Or a £50,000 note.

The world would truly be your oyster.

3-D printing has inevitably received its share of hype. But in this case, the excitement could conceivably be justified. 3-D printing is one of 12 technologies that the McKinsey Global Institute recently identified as having high potential for economically disruptive impact between now and 2025.

Technology can be sexy.

You have to be quite astute, sometimes, to dodge what may seem like manifestations of the latest fat.

Can robots be companions for the elderly?

However, some of the aspects of the NHS are much more mundane; even depressing.

Professor Michael Porter, the world expert in competition, often used to cite in lectures at Harvard how technology itself often doesn’t necessarily mean ‘a competitive advantage’.

This year, it was announced that the costs of the multibillion-pound national health IT programme abandoned by the government are set to continue rising significantly.

The Commons public accounts committee issued the warning as it branded the scheme one of the “worst and most expensive contracting fiascos” in the history of the public sector.

And yet – curiously at the same time – the UK now needs to become world class at developing, testing and rapidly

diffusing the best new technologies and practices.

In June this year, NHS England called on the public, NHS staff and politicians to have an open and honest debate about the future shape of the NHS in order to meet rising demand, introduce new technology and meet the expectations of its patients. This is set against a backdrop of “the funding gap”.

New technology is considered either an opportunity or a threat, depending on how expensive it is.

But a new technology doesn’t necessarily need to be expensive.

A “disruptive innovation” is an innovation that helps create a new market and value network, and eventually goes on to disrupt an existing market and value network (over a few years or decades), displacing an earlier technology.

The term is used in business and technology literature to describe innovations that improve a product or service in ways that the market does not expect, typically first by designing for a different set of consumers in a new market and later by lowering prices in the existing market.

The concern, however, is that the NHS faces tighter financial constraints, a plethora of new private providers will seek new ways of capitalising on the new NHS market. In economic terms, the Health and Social Care Act (2012) has produced the correct ‘rent extraction’ environment for companies seeking to maximise shareholder dividend.

The added concern for some healthcare analysts is that this is diverting resources away from front-line care.

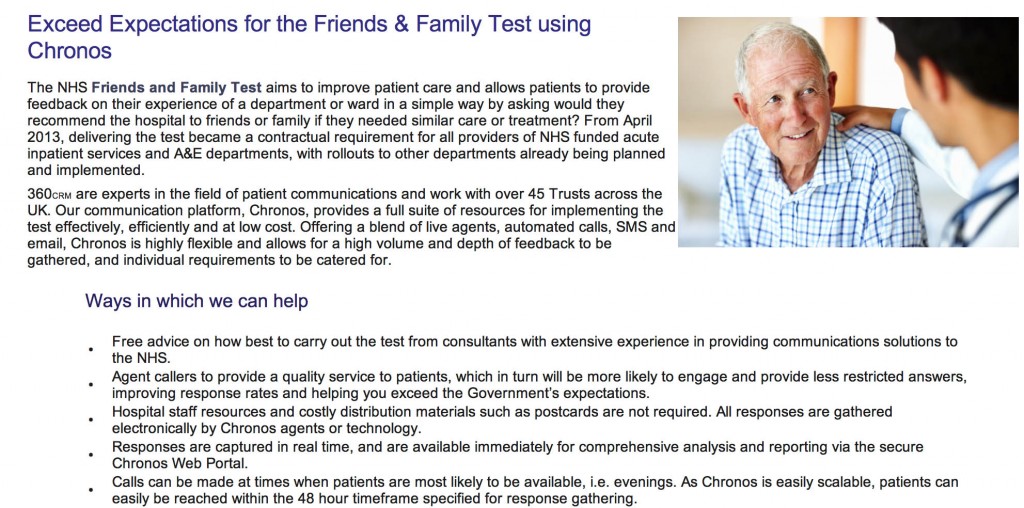

For example, here is a pitch from a provider of “The Friends and Family Test”:

Please click here for a magnified version of this image. You can read from the first paragraph why commissioning this would be so attractive to NHS Trusts, as they all gear up to be Foundation Trusts by the end of 2014.

Publishing has seen innovations which have been ‘revolutionary’. Similar to Gutenberg’s printing technology that replaced handwritten manuscripts, digital technology is replacing printed books. Paper replacing parchment; desktop publishing replaced typesetting, and so on.

Cheaper doesn’t though necessarily mean worse. An ipad to screen for dementia isn’t necessarily better than pen-and-paper.

Some years ago, a group published a paper in the BMJ.

They had sought to evaluate evaluate a brief screening test, the TYM (“test your memory”), in the detection of Alzheimer’s disease. They examined its efficacy in outpatient departments in three hospitals, including a memory clinic.

They involved a large number of people. They included 540 control participants aged 18-95 and 139 patients attending a memory clinic with dementia/amnestic mild cognitive impairment.

They found that the TYM can be completed quickly and accurately by normal controls. They concluded, by comparing the test’s performance to other instruments, that it was a powerful and valid screening test for the detection of Alzheimer’s disease.

Another system of the body provides an equally interesting example.

PCP is an infection of the lungs caused by Pneumocystis jiroveci, which is a common micro-organism in people. It causes disease only in people with weakened immune systems, such as those who have had transplants, chemotherapy, or advanced HIV infection. As the infection progresses, the air spaces in the lungs fill with fluid, making it harder to breathe.

You can apply a ‘pulse oximeter’ to the index finger of an individual to measure non-invasively an oxygen saturation. A ‘tight’ chest and shortness of breath can occur when climbing stairs. This can be evidenced by the pulse oximeter’s change in readings from high to low. This is not a particularly expensive test, say compared to a high-resolution CT scan.

These aren’t of course definitive tests, but simply demonstrations of cheapish equipment can be helpful in medicine without exploding the technology budget.

As a final example, one can think of home pregnancy tests which detect the hormone human chorionic gonadotropin, or hCG. In general, the human body produces detectable levels of this so-called pregnancy hormone only when a blastocyst has implanted into the wall of the uterus. While false positives are rare, there are are several interesting causes of a positive pregnancy test. Very rarely, a positive pregnancy test may be the first indication of a tumour in the ovaries, uterus or endometrium. The amount of hCG secreted by these tumours will vary dramatically depending on the type of tumour. Levels can be sky-high on occasion. Even sophisticated algorithms on computers can get it wrong.

Part of the well-founded anxiety in non-clinicians operating the NHS 111 algorithm is that a call handler might miss a life-threatening meningitis if the correct constellation of symptoms around a headache is missed. The end-point of such calls apparently from the algorithm is ‘go to A&E’ or an ambulance, so hopefully such cases are picked up.

Stephen on the ‘Lex Futurus’ blog (@lexfuturus is PwC’s lead in innovatively transforming legal services) hit the nail-on-the-head for the legal industry, and lessons should be learnt by the medics too.

It’s all about using technology intelligently, stupid.

We now live in a world of email, smart phones, automated document production and Nespresso machines. We have better technology than Roger Moore’s 007 (although there are meetings I would have dearly loved access to his exploding pen) yet, we are working harder and not necessarily smarter.

For in-house lawyers, there should be a “thinking premium” (unless they can negotiate better hours with their CEO) which the technology proffers them, to allow observation, analysis, reflection and strategising – to lift in-housers up from the tyranny of case-by-case reactivity but to think on a proactive basis at an enterprise level.Instead of the “silver bullet” technology promises, in many cases IT would appear to add to the burden of legal teams, requiring them to extract reports, manipulate into excel, collate additional data manually or, in some cases, do and enter everything twice.

..

In truth, we are sold IT as a panacea – the answer to all our many woes. Well choreographed presentations are whizzed through but smart tech-types, demonstrating how their solution is the key to unlocking our efficiency... IT can be game changing – just make sure you know the game your playing and that you’ve got the tactics mapped out.

These are lessons which could be beneficially considered by those in NHS procurement too.

And it’s likely that assistive technology and telecare will impact, for the public good, in the dementia care of the future.

So like all friends, choose your type of technology carefully?

[Disclaimer: Do not rely on any information in this blogpost.]

The war over Jarman’s data

1. Introduction

The fiasco over the HSMR is now of totemic proportions.

In many ways, the battle over the Channel 4 headline story of Wednesday saying “for the first time” that hospital mortality rates in the UK were considerably higher than other jurisdictions has become more totemic than the notorious “War over Jennifer’s Ear“. To give him credit, Prof Brian Jarman (@Jarmann) is always very helpful on Twitter. There can be a temptation to play the man not the ball, but Jarman has a very distinguished professional record as a member of the medical profession as part of the St. Mary’s Hospital/Imperial College centres in London. By his own admission, his first degree was in physics, and his PhD on Fourier analysis of seismic wave propagation. He changed to medicine age 31. There is absolutely no doubt that Prof Brian Jarman is an incredibly bright man. On the basis of presumption of innocence under English law, it is critical to assume that Prof Jarman did not intend to mislead the general public through the reporting of his claims over hospital mortality statistics. This is indeed consistent with the positioning of excellent patient safety campaigning groups who overall feel that a discussion over the statistics is a genuine offense to the misery of relatives (and families) who have suffered. There is perhaps an issue of whether Jarman was particularly reckless in how such data might be presented before a fearful public, and possibly how Jarman’s data are presented in the media, following the Telegraph and similar reports and this week’s Channel 4 presentation, in the future might be the best surrogate guide to Jarman’s true intentions.

The Channel 4 website report, “NHS hospital death rates among worst, new study finds“, is here.

“NHS chief Sir Bruce Keogh says he is taking very seriously figures revealed by Channel 4 News which show that health service patients are 45 per cent more likely to die in hospital than in the US.”

According to this Channel 4 website report:

“The figures prompted Sir Bruce Keogh, medical director of the NHS, to say he will hold top-level discussions in a bid to tackle the problems. I want our NHS to be based on evidence. I don’t want to disregard stuff that might be inconvenient or embarrassing…I want to use this kind of data to help inform how we can improve our NHS,” he told Channel 4 News.I will be the first to bring this data to the attention of clinical leaders in this country to see how we can tackle this problem.”

2. The methodology of the “hospital standardised mortality ratios” (HSMRs)

The methodology of the ‘hospital standardised mortality ratios‘ is well known to Sir Bruce Keogh. The wider criticisms of the HSMR have been extensively discussed in the medical press, see for example “Using hospital mortality rates to judge hospital performance: a bad idea that just won’t go away” (in the BMJ, April 2010).

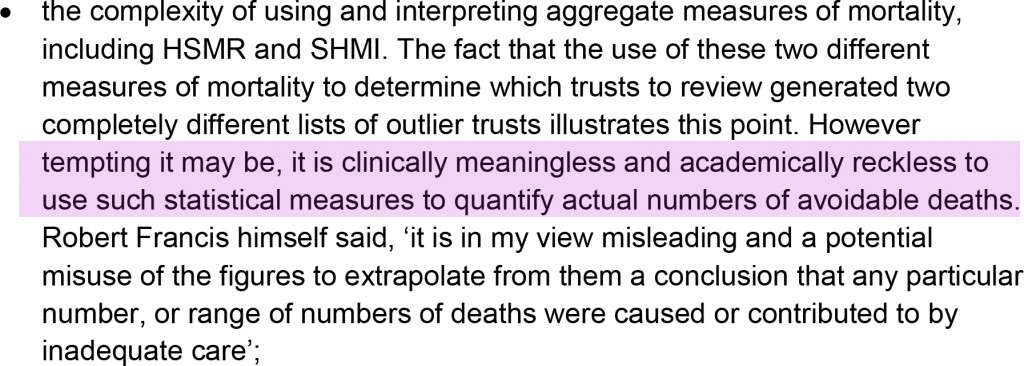

In the widely publicised “Review into the quality of care and treatment provided by 14 hospital trusts in England: overview report” published from earlier this year, it is stated:

Jarman’s ‘discovery’, in a flourish worthy of ‘Gone with the Wind’ perhaps, is described thus:

“What he found so shocked him, he did not release the results. Instead, he searched – in vain – for a flaw in his methodology and he asked other academics to see if they could find where he might have gone wrong. They, too, could not find fault.”

The question remains: what happened in the intervening nine years which prevented any activity culminating in professional peer review?

3. These data were indeed presented as far back as 2004

The Channel 4 reporting was sensational as illustrated in this excerpt from the Channel 4 report by Victoria Macdonald:

“So now he is releasing the findings. And they are shocking. The 2004 figures show that NHS had the worst figures of all seven countries. Once the death rate was adjusted, England was 22 per cent higher than the average of all seven countries and it was 58 per cent higher than the best country.”

The data are even known to the Department of Health as evidenced by Jarman himself here:

A tweet shared by Brian Jarman provides a link to the presentation of the data in 2004.

A tweet shared by Brian Jarman provides a link to the presentation of the data in 2004.

The starting point of the report was to go to the Mayo Clinic:

“Because of confidentiality issues we are not allowed to name the other countries. But America stands out in the data for its lower mortality rates. So we went to find out why. At the Mayo Clinic Hospital in Phoenix, Arizona, they are in the best two per cent in the country. It is an impressive hospital, with piano music playing in the lobby and sunshine streaming into the rooms.”

4. Concerns about the data

Any (reasonable) reviewer of these data, particularly given the bold and significant nature of the claims therein, will be concerned about the ‘quality’ of the data, in much the same way Jarman is concerned about the ‘quality’ of healthcare. This is particularly so if one adopts the approach of ‘treating the data’ rather than ‘treating the clinical patient’, which many clinicians would not advocate anyway in isolation.

This ‘confidentiality issue’ about the manner in which these data were provided is confirmed in a recent tweet by Jarman:

In the absence of clarity of what these confidentiality issues precisely are, it is hard to deduce fully what it is exactly that is so prohibitive for Jarman publishing his data. Many senior academics indeed converge on the notion that the publication of these data would be a useful contribution to the field, provided that the publication were properly refereed from two perspectives. These perspectives are that the statistical techniques used are sound. The second perspective is from a clinician’s perspective that the correct public health policy issues have been identified, and analysed correctly using available global evidence, and the citation of relevant background assumptions and confounding factors. Whilst it is hard to conceive that Governments have been withholding publication of data on public policy grounds (and arguably there is no more important a policy issue than a country’s mortality), it is possible that individual private companies may not wish to disclose fully confidential data. In the private sector even, such lack of disclosure of confidential data has led to accusations of fraud and discussion of mitigation, because of the sensitivity of such data to the markets in the dividend signalling theory. Academics have suggested to Jarman on Twitter that it might be possible to publish these data using the techniques of anonymisation or pseudo-anonymisation, as is prevalent in contemporaneous scientific research, but again no answer has been readily provided.

In the absence of clarity of what these confidentiality issues precisely are, it is hard to deduce fully what it is exactly that is so prohibitive for Jarman publishing his data. Many senior academics indeed converge on the notion that the publication of these data would be a useful contribution to the field, provided that the publication were properly refereed from two perspectives. These perspectives are that the statistical techniques used are sound. The second perspective is from a clinician’s perspective that the correct public health policy issues have been identified, and analysed correctly using available global evidence, and the citation of relevant background assumptions and confounding factors. Whilst it is hard to conceive that Governments have been withholding publication of data on public policy grounds (and arguably there is no more important a policy issue than a country’s mortality), it is possible that individual private companies may not wish to disclose fully confidential data. In the private sector even, such lack of disclosure of confidential data has led to accusations of fraud and discussion of mitigation, because of the sensitivity of such data to the markets in the dividend signalling theory. Academics have suggested to Jarman on Twitter that it might be possible to publish these data using the techniques of anonymisation or pseudo-anonymisation, as is prevalent in contemporaneous scientific research, but again no answer has been readily provided.

5. The utility (and futility) of cross-jurisdictional comparisons

The financial situation of the Mayo Clinic itself is known to be strong, with a colossal amount of income per patient at the Mayo Clinic compared to a patient in the English National Health Service:

“But a copy of the clinic’s consolidated financial report obtained by the Pioneer Press shows total revenue of $8.48 billion in 2011. That was an increase of $533 million, or nearly 7 percent over revenue of $7.94 billion during the previous year. Income from operations increased by 18 percent, growing from $515.3 million in 2010 to $610.2 million last year, according to the financial report. “This is very strong,” said Steve Parente, a professor of finance at the University of Minnesota’s Carlson School of Management. “In terms of pure operations, they’re doing quite well….Their grants and contracts are going up, too,” said Parente, who reviewed the financial report.””

A pertinent issue is whether the hospital episode statistics are themselves reliable. Prof Jarman quoting other reports feels that they are reliable (see tweet). However, this is in contradistinction from other reports sourced at the Royal College of Physicians of London (as described in a previous Guardian article):

“Currently the public can use the NHS Choices website to help them choose a hospital for treatment. NHS Choices, and the information used by Dr Foster, is based on “Hospital Episode Statistics” (HES) data, which the NHS says is “authoritative and essential”. However, NHS insiders say the information, usually collected by administrative staff from patient records, is unreliable.Professor John Williams, director of the health information unit at the Royal College of Physicians, carried out a study into HES data and found a significant number of operations were recorded inaccurately. He has called for a change in the way data is collected, saying flaws in the HES database were exposed as long ago as 1982.”

Hospital death rates, particularly if followed over time, can give useful warning of problems, as Sir Bruce Keogh has stated. Dr Jacky Davis in a subsequent Channel 4 interview (see below) was asked about the ‘smoke detector’ use of HSMRs as being pivotal in warning about problems.

It is, for example, argued that the issues in Mid Staffs would not have been exposed, but for the HSMRs. This argument is relatively convincing, but it is also argued that any reader of the local papers in Mid Staffs would have been aware of the problem long before the official HSMR figures emerged. Dr Jacky Davis in her C4 interview on Thursday, in reply, admitted that this ‘smoke detector argument’ might be true, but explained further ‘if there’s smoke going up you have to make sure – is there a fire there?‘. This is intuitively true, as well as the notion that the mortality rate in any given hospital will depend on the numbers of people who are actually dying ‘on site’. In general of course variation of data in other jurisdictions are likely to relate to regional variation of the care of palliative care patients, for example, and also where the funding for medical care is coming from (for example, the location of death may be an artifact of the conditions of private insurance funding.)

It is, for example, argued that the issues in Mid Staffs would not have been exposed, but for the HSMRs. This argument is relatively convincing, but it is also argued that any reader of the local papers in Mid Staffs would have been aware of the problem long before the official HSMR figures emerged. Dr Jacky Davis in her C4 interview on Thursday, in reply, admitted that this ‘smoke detector argument’ might be true, but explained further ‘if there’s smoke going up you have to make sure – is there a fire there?‘. This is intuitively true, as well as the notion that the mortality rate in any given hospital will depend on the numbers of people who are actually dying ‘on site’. In general of course variation of data in other jurisdictions are likely to relate to regional variation of the care of palliative care patients, for example, and also where the funding for medical care is coming from (for example, the location of death may be an artifact of the conditions of private insurance funding.)

However, arguably reliable comparison of such data internationally is fraught with difficulties, as Prof Walter Holland and colleagues found out when they published the European Atlas of Avoidable Deaths in 1988. Prof Holland is an eminent expert in public health and a visiting Chair at the London School of Economics. Since total mortality rates in the UK are similar, or lower, than in the United States, as a large proportion of the population in both countries die in a hospital such a difference seems unlikely, according to Holland. To compare hospital mortality rates between hospitals, whether in one or more countries, arguably it is necessary to take into account such factors as availability of discharge facilities, e.g. hospices, hospital admission criteria, length of time in hospital, and many other procedural and cultural factors, according to the eminent Holland.

Comparison of outcomes for individual conditions is even more difficult because of differences in diagnostic and coding procedures which have been illustrated many times. In a famous paper “Evidence of methodological bias in hospital standardised mortality ratios: retrospective database study of English hospitals” published in the BMJ in 1999, this coding problem was identified thus:

“Our findings suggest that the current Dr Foster Unit method is prone to bias and that any claims that variations in standardised mortality ratios for hospitals reflect differences in quality of care are less than credible.8 12 Indeed, our study may provide a partial explanation for understanding why the relation between case mix adjusted outcomes and quality of care has been questioned.24 Nevertheless, despite such evidence, assertions that variations in standardised mortality ratios reflect quality of care are widespread,25 resulting, unsurprisingly, in institutional stigma by creating enormous pressure on hospitals with high standardised mortality ratios and provoking regulators such as the Healthcare Commission to react.20“

In our jurisdiction, for example, the proportion of surgery done as elective day cases is reported to be quite high. Unfortunately the data presented by Jarman in his original 2004 presentation and the Wednesday Channel 4 package are inadequate alone for anyone to determine the validity of the conclusions or the methods used. This is a striking media story but unfortunately has not been subjected to proper scrutiny. This will be essential for policy in English health policy, particularly in the critical issue of patient safety, to progress; and progress it must not on the basis of emotion or soundbites.

6. A wider issue

Prof Jarman has consistently stated that he is in favour of a NHS funded by taxation, which is different from the attitude of libertarians and the Mayo Clinic, as shown here:

Critics of Jarman have felt that his criticisms of some foci of the delivery of care undermine the daily work of clinicians across the country, and may even undermine the doctor-patient relationship so pivotal for the work of clinicians in real life (see for example here).

Critics of Jarman have felt that his criticisms of some foci of the delivery of care undermine the daily work of clinicians across the country, and may even undermine the doctor-patient relationship so pivotal for the work of clinicians in real life (see for example here).

Jarman and supporters feel, however, that for ages criticisms of poor quality of care in the NHS have been suppressed, and that there is a professional duty to speak up about such poor care to improve the NHS. However, critics of Jarman feel that such an approach ‘in the wrong hands’ is merely providing ammunition for further marketisation and privatisation of the NHS, and that Jarman is carrying out the ‘handy work’ for politicians to see this ideological goal come into fruition.

Jarman and supporters feel, however, that for ages criticisms of poor quality of care in the NHS have been suppressed, and that there is a professional duty to speak up about such poor care to improve the NHS. However, critics of Jarman feel that such an approach ‘in the wrong hands’ is merely providing ammunition for further marketisation and privatisation of the NHS, and that Jarman is carrying out the ‘handy work’ for politicians to see this ideological goal come into fruition.

This debate is intense with accusation and counter-accusations, but the volume of criticism regarding the NHS article headlining Channel 4 news on Wednesday is a testament to how the public will not accept unqualified comparisons of the NHS with other jurisdictions either. The ensuing analysis has further put the spotlight on Jarman’s data, but this can be no bad thing either. The medical and nursing professions, and their regulatory bodies, will wish for all involved to maintain the reputation, trust in and confidence in their work, but this is only possible if the work is ‘fit for purpose’. Politicians can slag off the NHS to an extent to which clinicians would likely become disciplined for, and it is this contradiction which raises eyebrows.

This debate is intense with accusation and counter-accusations, but the volume of criticism regarding the NHS article headlining Channel 4 news on Wednesday is a testament to how the public will not accept unqualified comparisons of the NHS with other jurisdictions either. The ensuing analysis has further put the spotlight on Jarman’s data, but this can be no bad thing either. The medical and nursing professions, and their regulatory bodies, will wish for all involved to maintain the reputation, trust in and confidence in their work, but this is only possible if the work is ‘fit for purpose’. Politicians can slag off the NHS to an extent to which clinicians would likely become disciplined for, and it is this contradiction which raises eyebrows.

7. Conclusion

Notwithstanding, it is clear that the fundamental mistake is that it was perceived by some that the Channel 4 report represented irresponsible journalism in that the assumptions were not accurately stated, it suffered from bias by omission by lack of explanation about the surrounding issues (not least presenting Keogh as somebody who tacitly endorsed the uncritical issue of the HSMR, which is false), and basically left a very ugly taste in many people’s mouths. It did no favours for the reputation of, trust in, and confidence in Channel 4 news reporting either that night (Wednesday), but in fairness to Channel 4 news they hosted an interview with @DrJackyDavis – Co-Chair of the NHS Consultants Association – the following evening (Thursday).

However, it is impossible to deny the value of the discussion which has ensued after this dreadful report. The policy situation is precarious, aggravated by certain Ministers of the Crown lying blatantly in the whole saga over a period of months in the current Government.