Home » Equality

Some should be very afraid of Thomas Piketty. We may not be all customers of the NHS now.

Let me buy into the ‘Piketty bubble‘ momentarily, in a tenuous discussion of his book ‘Capitalism in the 21st century’ in relation to the National Health Service.

Since the 1980s, a change in terminology began in England.

Patients in the National Health Service became increasingly known as ‘users’, or as ‘customers’. Throw forwards to 2014, and Chuka Umunna in the UK Labour Party proudly boasts ‘we are all capitalists now’.

Cynics might argue that ‘bringing the lowest out of the poverty’ makes everyone into a capitalist, but I probably wouldn’t talk in such strong terms.

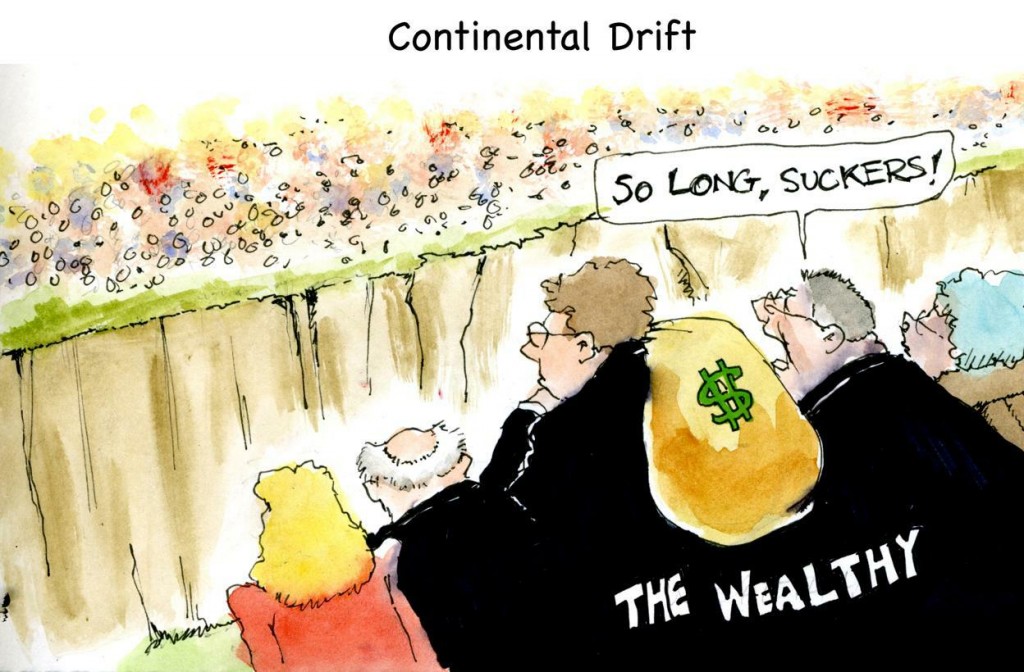

There is a clearly a huge public appetite for a frank discussion on ‘inequality’, on how wealth can be accumulated in the very few and how the super-rich are growing ever distant from those of the bottom of the wealth scale.

Piketty argues that for ‘disruptive’ super events such as the Great Depression or World Wars, inequality would have got far worse.

The most solid part of Piketty’s narrative, as I am sure the author himself would himself concede, is the historical part reviewing what happened in the 19th Century.

And yet, even if the super-élite such as Lord Stewart Wood and Tim Livesey of Ed Miliband’s circle don’t want to buy into it public, a fairer re-distributive taxation system appears not to be on the cards.

Such a fair taxation system is the most parsimonious solution to the ‘funding gap’ presented before the NHS. But to the exasperation of right-wing think tanks the NHS ‘sustainability gap’ has been revealed finally as the Emperor’s New Clothes.

The NHS is a system packed full of brilliant minds but who are collectively underfunded.

And that’s also where the narrative of the right-wing think tanks also runs into problems. Much to the annoyance of the same right-wing think tanks, ‘patients’ have not been successfully rebranded as ‘customers’. We might not be all capitalists now.

In fact, it may be more specific than that. ‘Google’ is the new ‘essential utility company': are we all consumers of multinational corporates now?

And this matter creates a further important ideological discussion, reincarnated for modern times.

It was mooted only yesterday by Prime Minister David Cameron that Labour has resisted all successful transfers of resources into the private sector, such as British Telecom or Royal Mail.

Most members of the Coalition governing parties can bring themselves to mention the ‘P’ word with regards to the NHS, especially with the wealth of a few investors who have benefited handsomely from the initial public offering of the Royal Mail having gone up into the stratosphere.

But the idea of wealth being concentrated in the hands of the few private sector operators goes to the heart of the public displeasure of the outsourcing and privatisation of the NHS through the Health and Social Care Act (2012).

That’s because here it is a matter of life or death. In simple terms, nobody wants to live in a society where a child with a rare genetic disorder, such as juvenile metachromatic leukodystrophy, is denied a potentially life-saving treatment, such as bone marrow transplantation, because of an inability to pay.

This argument also reaches another level, when you consider that all the main political parties are gradually converging on the concept of unified personal budgets for health and social care. While ‘top up payments’ appear to have been ruled out, it is uncertain whether this pretence will be kept up for much longer.

Lord Norman Lamont, not known for his intellectual prowess, claimed last night in his skinny dipping into the Piketty bubble that the only way to achieve ‘equality of opportunity’ would be to abolish inheritance tax. This is clearly as ludicrous as saying that the only way to achieve ‘equality of opportunity’ for alternative qualified (private) providers, or economic parity, would be to abolish the NHS. Oh wait.

The promise that the NHS is free, comprehensive and free at the point of need may be in large part correct, but is clearly not wholly true if very expensive treatments, such as the breast cancer drug Kadcycla, are rationed.

Shareholders and directors of large organisations may have a rather different opinion from those carers on zero-hour contracts who literally don’t know whether they’re coming or going.

There is an economic distinction between the ‘inequality’ arguments and the ‘cost of living’ arguments, but the former may indeed more easily adaptable for Ed Miliband’s new political messaging guru David Axelrod.

In terms of the sheer politics, campaigning on inequalities in health service provision is a big win (or “low hanging fruit”); some other, albeit hugely important, public health topics less so.

Indeed, some should be very afraid of the translated Thomas Piketty narrative, not least certain prominent members of the main political parties.

Piketty has helped to show that economics is not a ‘dismal science’, but is profoundly relevant to our society.

And, for that reason alone, we may not be all customers of the NHS now.

Is prevention of dementia a pipe dream?

Predicting the future on the basis of your past is of course the ultimate goal of the shopping industry.

It also seems to be the goal of healthcare, as consumer behaviour and patient care appear to converge in ever-marketised healthcare.

When you ‘sign up’ for a health subscription somewhere, one day, it’s possible you’ll be offered “packages” most suitable for you. Consider them like targetted adverts on Facebook. Of course, with disease registries compiled on your behalf by public health through data sharing, tomorrow’s world is getting ever closer.

So how much of dementia is in your ‘control’, if you haven’t yet developed it?

Is prevention of dementia a pipe dream? There are, after all, many factors which we’re born with which can have a huge influence. These are known as generic factors.

Amazon, the world’s largest online retailer, is already testing unmanned drones to deliver goods to customers. The drones, called Octocopters, could deliver packages weighing up to 2.3kg to customers within 30 minutes of them placing the order. Amazon has filed a patent that will allow it to ship a package to you before you even know you’ve bought it.

Now back to the past. Back to Black in fact.

The Black report was a 1980 document published by the Department of Health and Social Security (now the Department of Health) in the United Kingdom, which was the report of the expert committee into health inequality chaired by Sir Douglas Black. It was demonstrated that although overall health had improved since the introduction of the welfare state, there were widespread health inequalities.

Full Text of the Black Report, supplied by the Socialist Health Association website.

Surprisingly enough, it’s not all doom and gloom.

Modulating the environment might have some sort of impact on prevention of dementia, even if we don’t yet know how big or small this impact is.

The study of exceptionally long-living individuals can inform us about the determinants of successful aging. There have been few population-based studies of centenarians and near-centenarians internationally. But a recent study involving individuals 95 years and older were recruited from seven electoral districts in Sydney provided evidence that dementia is not “inevitable” at this age and independent living is common.

Low socioeconomic status in early life is well known to affect growth and development, including that of the brain; and it has also been shown to affect the risks of other chronic diseases.

Over a decade ago, a real attempt was made to relate early socioeconomic status to later dementia. We found results consistent with the hypothesis that a healthier socioeconomic environment in childhood and adolescence leads to more “brain reserve” (the brain’s ability to cope with increasing age- and disease-related changes while still functioning) and less risk of late-life dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, later on.

Results from two major cohort studies, led by the University of Cambridge and supported by the Medical Research Council, have reveal that the number of people with dementia in the UK is substantially lower than expected because overall prevalence in the 65 and over age group has dropped.

Three geographical areas in Newcastle, Nottingham and Cambridgeshire from the initial MRC Cognitive Function and Ageing Study (CFAS) examined levels of dementia in the population. The latest figures from the follow up study, CFAS II, show that there is variation in the proportion of people with dementia across differing areas of deprivation, suggesting that health inequalities during life may influence a person’s likelihood of developing dementia.

The prevalence of dementia in the general population might be subject to change. Factors that might increase prevalence include: rising prevalence of risk factors, such as physical inactivity, obesity, and diabetes; increasing numbers of individuals living beyond 80 years with a shift in distribution of age at death; persistent inequalities in health across the lifecourse; and increased survival after stroke and with heart disease.

By contrast, factors that might decrease prevalence include successful primary prevention of heart disease, accounting for half the substantial decrease in vascular mortality, and increased early life education, which is associated with reduced risk of dementia.

The study was led by Professor Carol Brayne from the Cambridge Institute of Public Health at Cambridge University. She opined that whether or not these gains for the current older population will be borne out in later generations might depend on whether further improvements in primary prevention and effective health care for conditions which increase dementia risk can be achieved, including addressing inequalities.

In fact, it has been recently appreciated that cardio-metabolic risk factors have been associated with poor physical and mental health.

An association of low education with an increased risk of dementia including Alzheimer’s Disease, the most common cause of dementia globally, has been reported in numerous cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Education and socioeconomic status are highly correlated, it turns out.

The reserve hypothesis has been proposed to interpret this association such that education could enhance neural and cognitive reserve that may provide compensatory mechanisms to cope with degenerative pathological changes in the brain, and therefore delay onset of the dementia syndrome.

The complexity of people’s occupations also positively influences cognitive vitality, and this relationship becomes increasingly marked with age.

Further evidence from studies suggests that a poor social network or social disengagement is associated with cognitive decline and dementia.

The risk for dementia including Alzheimer’s Disease was also increased in older people with increasing social isolation and less frequent and unsatisfactory contacts with relatives and friends. Rich social networks and high social engagement imply better social support, leading to better access to resources and material goods.

Previous studies have also shown that social determinants not directly involved in the disease process may be implicated in the timing of dementia diagnosis. Possibly the living situation is related to the severity of dementia at diagnosis. If so, primary care providers should have a low threshold for case-finding in older adults who live with family or friends?

Regular physical exercise was reported to be associated with a delay in onset of dementia including Alzheimer’s Disease among cognitively healthy elderly.

In the Kungsholmen Project, the component of physical activity presenting in various leisure activities, rather than sports and any specific physical exercise, was related to a decreased dementia risk. It is generally thought that physical activity is important not only in promoting general and vascular health, but also in promoting some form of brain rewiring.

Various types of mentally demanding activities have been examined in relation to dementia in general, including knitting, gardening, dancing, playing board games and musical instruments, reading, social and cultural activities, and watching specific television programs, which often showed a protective effect.

So it really might not all the doom and gloom, and certainly we are much further forward than we were 33 years ago with the publication of “The Black Report”.

For the record, this Report doesn’t even mention dementia.

Prof Alistair Burns in New Scientist writing “Dementia: A silver lining but no room for complacency” summarised elegantly the situation as follows, on 10 January 2014:

“While it is true that there is no cure, the findings suggest that prevention is at least possible. This must surely explain any reduction in prevalence, so what might be behind it? Improved cardiovascular health, better diet and higher educational achievement are all plausible explanations. This opens up the possibility that people who are able to take control of their lives can reduce their individual risk of dementia.”

Should “genetic discrimination” be proposed as an amendment to the Equality Act (2010)?

One of the ways in which a district hospital differs from a large foundation trust in the NHS is that you’re more likely to take part in a drug trial or research in the large foundation trust.

Currently, European law is having to negotiate the ‘data protection’ directive.

Under EU law, personal data can only be gathered legally under strict conditions, for a legitimate purpose.

Furthermore, persons or organisations which collect and manage your personal information must protect it from misuse and must respect certain rights of the data owners which are guaranteed by EU law.

The needs of data sharing, for example by GPs and hospitals in future of the NHS, will be different from the needs of the academic research community, and somehow this will need ultimately to be reflected in our law.

The Equality Act 2010 in England and Wales is currently the key piece of legislation which allows claims of discrimination to be brought.

It bought together a number of existing laws into one place so that it is easier to use. It sets out the personal characteristics that are protected by the law and the behaviour that is unlawful. Under the Act people are not allowed to discriminate, harass or victimise another person because they have any of the protected characteristics.

Everyone in Britain is protected by the Act. The “protected characteristics” under the Act include age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion and belief, sex, and sexual orientation

When US sneezes, England catches a cold, it is alleged.

It is claimed that that many Americans fear that participating in research or undergoing genetic testing will lead to them being discriminated against based on their genetics.

Such fears may dissuade patients from volunteering to participate in the research necessary for the development of new tests, therapies and cures, or refusing genomics-based clinical tests.

To address this specific problem, in 2008 the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (“GINA”) was passed into US law, prohibiting discrimination in the workplace and by health insurance issuers. One wonders whether a genetic phenotype should be considered one day for an amendment in the Equality Act for overseeing such claims under discrimination law.

GINA prohibits issuers of health insurance from discrimination on the basis of the genetic information of enrollees. Specifically, health insurance issuers may not use genetic information to make eligibility, coverage, underwriting or premium-setting decisions.

Furthermore, issuers may not request or require individuals or their family members to undergo genetic testing or to provide genetic information.

As defined in their law, genetic information includes family medical history and information regarding individuals’ and family members’ genetic tests.

But why does this suddenly matter for “Our NHS”? The main reason is that there is a massive ‘data sharing’ drive in the UK.

There are in fact many emerging scenarios, where the empowerment of rights for patients can in fact run alongside potential apparent reasons for detriment.

Tim Kelsey, NHS England’s National Director for Patients and Information, wrote this week for NHS England:

“Transparency saves lives and it is a basic human right yet transparency, unlike heart surgery, is not mainstream in our health and care services. Last year, I took a vision to the EHI Live conference (held this week in Birmingham) to make transparency the operating principle of the new NHS. Data sharing between professionals, patients and citizens is the precondition for a modern, sustainable public service: how can we put patient outcomes at the heart of healthcare, if we cannot measure them? How can we help clinicians maximise the effectiveness of their resources, if they do not know where they are spent? How can we ensure the NHS remains at the cutting edge of statistical and medical science if we do not allow researchers and entrepreneurs safe access to clinical data?”

It is conceivable that ‘integration’ of the NHS and private insurance systems could be a feature of this future, as even this contributor to “Your Britain” observed.

MPs may wish to argue that citizens also need adequate protection, sometimes, from data sharing. This would, for example, be necessary if ever the ill-fated universal credit is integrated with health and social care personal budgets.

Currently, GINA prevents employers from using genetic information in employment decisions such as hiring, firing, promotions, pay, and job assignments.

Furthermore, GINA prohibits employers (for example, employment agencies, labour organisations, and apprenticeship programs) from requiring or requesting genetic information and/or genetic tests as a condition of employment.

It has been argued elsewhere that Beethoven might have been examples of individuals whom, if they had been tested for serious genetic conditions at the start of their careers, may have been denied employment in the fields in which they later came to excel. The jurisprudence for this issue is full of subtleties, which are discussed well in this well known blog on human rights law.

A ‘corporate capture’ of information held in the NHS has already begun, some might say. It is important that the legislature gets on top of this problem before it gets out-of-hand.

It’s the Equality stupid…

“The Conservatives lead on the economy”

“Labour is ahead on the NHS”

These appear to be the laws of nature of political philosophy in the UK.

And yet Ed Miliband has managed successfully to rearticulate the debate about the economy from the deficit to ‘what’s in it for me?’.

Ed Miliband wants the ‘squeezed middle’ to think that things have got much worse for them, with the cost-of-living far outstripping incomes, while the ‘super rich’ are happy on champagne on caviar.

Joking apart – the next general election, which will be intensively fought – will be dominated by the ‘cost of living crisis’, but the competence of the Conservative Party on the NHS (and their general approach to it) will be a factor.

Most people remember the famous sign in the Clinton campaign war room in 1992 as “It’s the economy stupid!” But what is often forgotten is the second phrase in the famous warning by Carville to Clinton campaigners to keep a sharp focus on the campaign’s message: “And don’t forget health care.” Andy Burnham MP now on numerous occasions has reminded supporters of this, including his fringe meeting for the New Statesman magazine in Manchester in 2012.

It’s obvious that Labour wishes to focus more on equality – or lack thereof.

Equality is more of a defining value in the Labour government than the liberal or social democratic philosophies, many believe. It is often politely derided in a textbook way, as by Michael Gove recently in a discussion of ‘One Nation’, as being rather ludicrous in that the Left appears to want to ‘force’ people to be equal.

Perhaps due to the rejection of “In place of strife” by a previous Labour government, the dying days of the Callaghan Labour administration was crippled by the activities of the Unions. The Conservatives hope that sufficient numbers of people will remember this misery from the 1970s to wish that a Labour government is never returned. That is why the “leveraging inflatable rat” is of such totemic political importance.

David Cameron has therefore vowed to crush Ed Miliband’s ‘1970s-style socialism’ as he put tax cuts, enterprise and opportunity at the heart of an election campaign to reprise the Tories’ defeat of Neil Kinnock. Cameron has condemned Labour’s ‘damaging, nonsensical, twisted economic policy’ and scoffed at what he called ‘Red Ed and his Blue Peter economy’ – saying it would heap ruin on Britain.

He has therefore asked the general public for the Conservatives “to continue the job” – not of continuing to stagnate the recovery, but to allow the UK economy to recover under his watch.

However, as Matthew d’Ancona observed today, the election of Bill de Blasio as New York’s 109th mayor is perhaps far beyond Manhattan and the Bronx. Campaigning against Michael Bloomberg’s 11 years in office as “a tale of two cities”, de Blasio easily won against his Republican rival, Joe Lhota. Since the formation of the moderate Democratic Leadership Council and the election of Bill Clinton, America has led the way in an avowedly centrist approach to progressive politics.

The question of equality in the UK is still hugely important.

When I went to Ed Miliband’s last ever leadership hustings in Haverstock Hill, I mentioned to him that Tony Blair’s autograph called “The Journey” doesn’t even have the word ‘inequality’ in the index. I remember him vividly smiling, and saying, “Oh really?”

One explanation for the rise in inequality under Thatcher, as measured by “the Gini coefficient”, is that the nature of inequality in the UK has changed. A ‘tax and benefit system by lifting incomes at the bottom, and by dragging down incomes at the top. Our top rates of tax remain relatively low by European standards (though certainly high by American ones), which means that redistribution to the poor tends to be paid for ‘by everyone’, not just by the rich.

More of our inequality is instead caused by top incomes ‘racing away’ from everyone else – with incomes at the very top of the distribution growing much faster than those in the middle under Labour. As Peter Mandelson famously said in 1998, “we (Labour) are intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich.” The dynamics of this inequality are particularly even now, and it is hotly debated as to whether inequality got any worse under Blair or Brown.

In an apparent boost for Osborne, the Treasury said it took £11.5 billion in income tax in April 2013 – a 10 per cent increase on the previous year. There had been fears the lower 45p rate could lead to a loss in revenue for the Government, with Labour branding it a “tax cut for millionaires”. However, Osborne had consistently argued that the 50p tax rate brought in by Gordon Brown in April 2010 did not substantially boost income tax receipts for Treasury coffers. The top rate of income tax had not been in existence for most of the 13 years of the Labour government just gone.

It is also argued that the Liberal Democrat policy of lifting more low and middle-income people out of paying tax altogether is resonating strongly with the general public.

Whatever is happening to the Gini coefficient currently, it has begun to unsettle the Right here in Britain that policies on the left now appear to be currying favour at a populist level:

the public is turning its back on the free market economy and reembracing an atavistic version of socialism which, if implemented, would end in tears. On some economic issues, the public is far more left-wing than the Tories realise or that Labour can believe. If you think I’m exaggerating, consider the findings of a fascinating new opinion poll from YouGov for the Centre for Labour and Social Studies.

The answers to two questions in particular made striking reading: “Do you think the government should have the power to control prices of the following things, or should prices be left to those selling the goods or service to decide?”; and “Do you think the following should be nationalised and run in the public sector, or privatised and run by private companies?”.

The results are terrifying: the UK increasingly believes that it is the state’s job to fix the “right” price, not realising that artificially low prices have always caused shortages and a far greater crisis whenever they have been tried. The great lesson of economics is that bucking markets with artificial price controls always fails; far better to address the root causes of the problem – high prices usually imply scarcity, or monopoly, or generalised inflation – or help those who are suffering directly.

The Liberal Democrats’ catchphrase is ‘a strong economy, and a fair society’.

While Clegg and Cameron appear to be quite chummy, it has been argued that their cultural background of affluence prevents them from understanding social justice and fairness properly.

The leadership, from the same public school roots, appears to have quite a lot in common, but there has been alarm at the schism between the grassroots’ feelings of the Liberal Democrats and Nick Clegg.

As symptomatic of an ‘unfair society’, today, five disabled people won their attempt to overturn the government’s abolition of a £300m fund that helps severely disabled people to “live a full life” in the community. The independent living fund helps 18,500 severely disabled people in Britain to hire a carer or personal assistant to provide round-the-clock care and enable them to work and live independent lives. The government proposed that the ILF be scrapped in 2015, and its resources transferred to local authorities. However, today’s Court of Appeal ruling found that the government had breached its equality duty in failing to properly assess what one of the judges called the “very grave impact” of the closure on disabled people.

The ruling, also at the Court of Appeal, in favour of Cait Reilly was also a two fingers salute at the fair society of Nick Clegg.

And bad luck seems to come in threes. At least.

For a Conservative-Liberal Democrat government which prides itself on ‘equality of opportunity’ for private providers competing with the NHS for taxpayers’ money, the NHS reconfiguration is going incredibly badly.

The Court of Appeal ruled last week that Health Secretary, Mr Jeremy Hunt, did not have power to implement cuts at Lewisham Hospital in south-east London. During the summer, Mr Justice Silber in the High Court had decided also that Mr Hunt acted outside his powers when he decided the emergency and maternity units should be cut back.

And equality keeps on rearing its head in the most unlikely (or likely) places. Take for example NHS resource allocation policy.

The most deprived areas will not lose out under the new formula for allocating funds to clinical commissioning groups, according to NHS England’s finance director Paul Baumann. During a Commons health committee hearing, Baumann revealed that the proposed new formula, to be described in detail in December 2013, will adjust for a health economy’s unmet need, where low life expectancy suggests people are not accessing health services.

It may all just be clever political positioning.

Indeed the Socialist Health Association believes in equality (“Equality”) based on equality of opportunity, affirmative action, and progressive taxation.

But, by reframing the question carefully, Miliband might find that it’s actually the Equality stupid…

Do the ‘sunny uplands’ of Labour’s NHS demonstrate ‘the dividend obsession’?

With Andy Burnham MP ‘restored’ as Shadow Secretary of State for Health after the latest Shadow Cabinet reshuffle, one can only assume that ‘responsible capitalism’ has not totally subsumed UK Labour’s health policy. For now, Chuka Umunna remains where he is. And Burnham can remain resisting the latest weekly smear campaigns (usually timed, to clockwork, on Twitter nowadays for Tuesdays).

Burnham himself talked this year at the Labour Party Conference of the need to put ‘people before profit’.

With many significant contracts being awarded under section 75 Health and Social Care Act (2012) to the private sector, and with section 164(1)(2A) of the same Act allowing the non-NHS income cap to be considerably higher than before, it is an important policy issue to revisit the ‘dividend obsession’.

Hardworking nursing union members might like to consider, now, quite how much hardworking taxpayers’ money is being siphoned off into the hands of private equity and venture capital firms through their companies.

Labour’s history with business can best be described as: “it’s complicated.” Goldman Sachs recently boasted on Twitter of their involvement with Chuka Umunna, the Shadow Secretary for Business, Innovation and Skills. And in the past Lord Mandelson has claimed to be ‘intensely relaxed’ about business.

Labour’s ‘track record’ on “inequality” still fuels discussion. Tony Blair’s ‘Journey’, an autobiography possibly as exciting as Morrissey’s, doesn’t mention the word “inequality” once.

British Gas announced yesterday that it is to increase prices for domestic customers, with a dual-fuel bill going up by 9.2% from 23 November. The increase, which will affect nearly eight million households in the UK, includes an 8.4% rise in gas prices and a 10.4% increase in electricity prices.

Energy company bashing has become the new banker bashing (and investment banking is another poorly regulated oligopolistic market). Nevertheless, Labour also wishes to be seen to encourage wealth creation. It perceives any message that it is ‘anti-business’ as dangerous. The political message is reconciled if Labour is able to divorce very large corporates which are perceived to be ‘shirking’, from small businesses which are perceived to be ‘striving’.

There is no doubt, however, that Labour instinctively wishes to be seen to be on the side of the employee/worker too. The evidence is that Labour warns about a growing number of people in part-time employment. They have also held their nose while the current Government have tried to implement the ‘Beecroft’ proposals. For the employer, an ability to sack an employee is seen as ‘flexibility’, so that a business plan can adapt easily to changing circumstances. For the employee, the ‘readiness to fire’ is seen as an indication that employers don’t actually give a stuff about employment rights, and the threat of insecurity for staff.

This is why the Fabian Society, in their analysis of why Gordon Brown became so unpopular, tried to hang their thoughts on the ‘aspiration vs insecurity’ scaffold. Interestingly, Ed Miliband has wished to emulate the ‘aspirational dream’ of Margaret Thatcher. Margaret Thatcher once claimed that, for every socialist who woke up, there had to be a Tory who woke up an hour earlier to work.

Any business these days needs to have due regard to its environment and its workforce. This is called ‘sustainability’, and this comprises the ‘people, profit, planet’ mantra of corporate social responsibility. It is a well established concept, which far precedes the ‘responsible capitalism’ now belatedly “accepted” after Miliband’s famous “high risk” conference speech in Liverpool in 2011.

The Conservatives have thrown everything but the kitchen sink at this attack on energy prices. The problem for Cameron is that this lunge is not only popular but populist. It frames the question ‘whose side is the government on?’ in an unappealing fashion. Error after error has seen the notion of a Conservative-led government being ‘out of touch’ being reinforced. This has perhaps been symbolised ultimately by Tory MPs simply re-tweeting on Twitter press releases from energy companies.

Whilst leadership theories both here in the UK and US are well articulated, the literature on the involvement of stakeholders in business is relatively embryonic. Freeman and Mendelow are generally accepted to be the ‘fathers’ of ‘stakeholder theory’.

But the tension of who runs the company in English law is noteworthy in two particular places. One is section 172 of the Companies Act (2006) which attempts to draft a primacy of shareholder dividend with regard to ‘stakeholder factors’. The second is the relative ‘paralysis of analysis’ which can occur with too many conflicting opinions of stakeholders, in relation to shareholders, in relation to the business plans of social enterprises.

Ed Miliband used the following as symbolic as the war against energy companies, which is perhaps more accurately described as a war against unconscionable profitability of shareholders. Cue his quotation from “SSE dividend information” this week in Prime Minister’s Questions:

The Right continue to argue that the war is a phoney one, given that Ed Miliband introduced these ‘green taxes’ in the Climate Change Act in the first place. A problem with this is that David Cameron voted for these taxes. The Right continue to argue that the market is ‘not rigged’. A problem with this is that David Cameron wishes to encourage the ability of a customer to ‘change tariff’, which presumably would be totally unncessary if the market were not ‘rigged’?

The Right continue to argue that the war is a phoney one, given that Ed Miliband introduced these ‘green taxes’ in the Climate Change Act in the first place. A problem with this is that David Cameron voted for these taxes. The Right continue to argue that the market is ‘not rigged’. A problem with this is that David Cameron wishes to encourage the ability of a customer to ‘change tariff’, which presumably would be totally unncessary if the market were not ‘rigged’?

The unconscionable profits, in economic terms, come about because it is alleged that the competitors, relatively few of them that there are, act in a coordinated way to set prices amongst themselves. It is further alleged that the competition regulators currently are unable to regulate this oligopolistic market effectively. Miliband’s ‘price freeze’ gives the Labour Party also some ‘breathing space’, in which to tackle the OFGEN problem.

Oligopolies are crowded markets with a relatively small number of competitors. This is why pricing can be ‘collusive’ in manner. They are notoriously hard to regulate.

We know about the whopping profit margins of key personnel in some of the markets like energy already, for example the front page of today’s Mirror newspaper. It is certain that exactly the same thing will happen in privatised health too in the UK. It’s no accident that the usual suspects run prisons, probation, workfare, benefits, security, and so on.

Fundamentally, Miliband’s narrative is extremely uncomfortable for the Conservatives. Far from being ‘liberalising’, in Miliband’s World, the markets end up fettering the behaviour of citizens. And this is a problem if citizens in Cameron’s World increasingly become mere consumers. If the market doesn’t work for Cameron’s consumer, the whole ideology collapses.

The Tories superficially may worry that the Hayek’s ‘Road to Serfdom’ has become a ‘Road to Slavery’, but ultimately their success depends on delivering a programme which benefits the big business and the City. Why else would Boris Johnson wish to go to legal war against Europe about banking bonus caps?

The narrative that Ed Miliband wishes to pursue of ‘putting people first’ is theoretically an amicable fusion between social democracy and socialism. While there are still clear faultlines in the approach, for example the maintained marketisation and privatisation of the NHS since 1979 (but which Burnham seems to wish to reverse), this narrative could prove to be even more popular and populist yet. Cameron’s World may just have been disrupted.