Home » Dr Shibley Rahman viewpoint (Page 3)

The NHS should not be like a conveyor belt

At first, I thought my criticism was simply because it was called “The Tony Blair Dictum”. For me, one of the most ‘successful’ Labour Prime Ministers in living history, and this is no time for hyperbole, was very good at knowing the price of everything and the value of nothing. This is what I thought was the heart of his failure to understand how modern business works, and the importance of people in the creation of value in the relatively new discipline of corporate social responsibility. But Blair was a lawyer and politician by trade.

The “Tony Blair Dictum” says “I don’t care who provides my NHS services ‘behind the curtain’, as long as it’s of the highest quality.’ Variants of it include the bit ‘as long as I don’t pay for it’, and indeed this bit is often tagged on to help to demonstrate that the reforms are not privatisation. However, if you include that the majority of contracts will be put out for competitive tendering, to avoid conflict, to the private sector – it is privatisation. It is taking away of resources to run a comprehensive, universal state-run service, and using the monies as consideration for entities running services for profit or surplus.

For ages, I thought my objection to this was purely in terms of my own business training. This training had taught me that increasing transactional costs was bound to magnify greatly the amount of wastage and inefficiency in running the system as a whole. Coupled with the loss of ‘economies of scale’, the likelihood of this process would be a fragmented service which costs money, and which is unlikely to be comprehensive. I don’t think my economic argument is incorrect. Nor do I think it’s somewhat disingenious for private contractors to run their services under the NHS logo, while it is well documented that programmed attacks on the NHS ideologically have taken place in parts of the media. Some parts of the media in an astonishing way have not reported on the ‘reforms’, estimated to cost about £2.5 bn so far, at all.

No, it’s not that. I think I find this Dictum potentially difficult, if it can be a different Doctor each time who sees you, and it doesn’t matter where they’ve come from. It suddenly dawned on me thanks to thinking about why Dr Jonathon Tomlinson (@mellojonny) loves general practice so much. My late father was a GP near Brighton for nearly 30 years, and he loved his job. He was a single-handed practitioner with a list of about 2500 with not a blemish on his professional record, and he did all his own on-calls. This means that he knew his patients (and often whole families) backwards – his families loved him as the community Doctor. He never breached medical confidentiality of course, but the continuity of care was of benefit to patients. This meant, like transactional costs, things would not get repeated to different people at different times, and things were not ‘lost in translation’ through Doctors reading the medical notes of other Doctors. My father knew his patients.

However, given that I have nothing to do with the medical profession, I am struck by how a ‘conveyor belt’ atmosphere had begun to emerge in the NHS, even in the brief time when I was a junior physician in busy Trusts in London and Cambridge. This means that the approach was that of a “production line”, what I would later know as ‘lean management’ (where it is very difficult to know the precise cause of clinical error because the system is literally firefighting all-of-the-time). In this production line, Doctors would never see the output of their combined efforts, the “product”, as the Doctor responsible for writing the discharge summary was invariably not the Doctor who had generated a ‘problem list’ when the patient was admitted to the Hospital in the first place.

This situation I feel is not unique to primary care, and certainly this is not meant to be any criticism of Group G.P. practices where Doctors are very keen to know the histories of all patients in their catchment. It is not meant to be a criticism of NHS Direct or the Out-of-Hours service, though the benefits of a patient seeing his or her own Doctor out-of-hours is not simply an issue of nostalgia. I think there is a clear parallel in the commodification of the legal profession. This commodification has seen law as not having a prominent place in one’s community (“There is no such thing as community” is possibly a more accurate phrase than “There is no such thing as society”), with the death of the high street law centre at odds with the flourishing multinational corporate law firms. Ironically, in the United States which has had a longer time to assimilate the effects of multinational corporates on modern life), there is now recognition from big-brand management consultancy firms that there is more value to be had inter-transactions rather than intra-transactions. This means that the approach of one ‘fee earner’ identifying and solving the legal problem, with that fee earner never to be seen again, is being replaced by a lawyer who is interested in the development of your issues over a long period of time.

This indeed had been the approach of the medical profession too. I remember being witness to some amazing physicians, who admittedly had remarkable memories but, who could remember events from the patients 20-30 years’ ago, which might have direct relevance to the symptom with which he or she was presenting today. Possibly, with the introduction of whole person care, this approach might take a comeback, and certainly continuity-of-care had previously been considered important for the conduct of medical professional life. Whether they intended to or not, my late Father and Dr Tomlinson have made me realise why I do actually find ‘The Tony Blair Dictum’, aside from macroeconomics, potentially very difficult.

What more can Labour do?

There’s an old adage that a third of all the people who know you will love you, no matter what you do, a third of people will hate you, no matter what you do, and the rest will simply be indifferent. It’s only one day every few years, but there will be millions on 7 May 2015 (if that’s the actual date of the General Election) who literally won’t be arsed to go down to their local election headquarters, because they feel their vote will not make any difference.

As usual, all of the nation’s woes and triumphs will be distilled into an election campaign, where you can sure that some things will be blown up out of all proportion, and other things won’t be discussed. Because of the short attention span of the media, and possibly even some readers/listeners, many issues will be distilled into soundbites. Remember the ‘tax on jobs’ debate we had last time in 2010 when the economy was actually recovering, prior to any discussion of ‘double dip’ or ‘triple dip’. You can rest assured that there’ll be no debate about A&Es closing, or the GPs’ out-of-hour contracts. Immigration is likely to be a headline though, not least because of Nigel Farage whose party has yet to get a MP elected to Parliament. However, the debate won’t go anywhere near how migrant workers are needed to keep the NHS alive, or the inevitability of globalism.

All Councillors I know are incredibly passionate about their ‘doorstepping’, and the general impression that I get is that the general public is generally more clued in than one might expect. However, because of the nature of politics, it’s going to be as usual pointless voting for certain parties in certain constituencies. Last time saw Nick Clegg being propelled into the limelight, with his famous tuition fees pledge. If there is to be another battle of the personalities, it is likely that Nigel Farage will be invited this time. Some gimmick like the “worm” will be back, and we’ll all be none the wiser until polling day.

So does this mean that politics doesn’t matter? Probably yes, as long as politicians fail to inspire potential voters. Many people on the left wing are just totally uninspired between a choice between Tory and Tory lite, and do not see a Labour leader leading on issues such as disability, a state-run NHS, or an economy which doesn’t take workers for a ride. Is there much Labour can do? Possibly get a move on, as people are totally sick to death of waiting for the climax of this neverending “policy review”, which many suspect will not answer certain fundamental issues, such as the fate of NHS Foundation Trusts. We seem to be waiting an eternity to find out what else will accompany ‘The Living Wage’ as a major manifesto issue, and if Labour didn’t do as well as they had wished for in the local elections it was simply because many voters did not consider them to be offering a valid alternative.

This is dreadful, when you consider quite how disastrously this current parliamentary term has gone for the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. Clearly, ‘One Nation’ is going to run into trouble, if voters in the South of England only feel as if they have a choice between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. If the Greens are becoming increasingly popular, it is because many people believe they deserve it: for example taking a strong stance against the Bedroom Tax. Labour indeed seems to be populated by ‘big personalities’, but there is no coherent strand to their philosophy at the moment. Their narrative appears to be a collection of sparse streams of consciousness, and this does not constitute a useful sense for direction.

It is not too late for Labour to remedy this. The reputation, deserved or not, that Labour is “fiscally incontinent” is going to be difficult to shift. Whether or not Labour was right to increase the deficit through recapitalising the banks as an emergency measure is not going to be a battle to be won now, ever. If anything, the Coalition have already won that battle, as they still cite the deficit for the reason that they are governing ‘in the national interest’. Labour can take the lead on a NHS which is universal and comprehensive. It can decide to push for an economy where workers have some security and long-term prospects in their job. It can also decide to represent the views of disabled citizens, many of whom have felt demonised by this Government.

Or else, despite great Councillors, it can carry on being… well… very bland.

If I could predict the future of my health, would I change my behaviour?

A major issue in economics certainly is how individuals cope with information. Much information is uncertain, so one’s ability to make rational decisions based on irrational information is a fascinating one. Predicting the future may be viewed as best kept as the bastion of astrologers such as Mystic Meg, but the likelihood of future outcomes is clearly of interest in the insurance industry. These decisions are not only helpful for people at an individual basis, but also hopefully useful for planning, rather than predicting, what is best for the population at large in future.

Angelina Jolie did not have cancer, but, in fact, like many women with breast cancer mutations, she had the radical surgery to lower her risk. She, at the age of 37, has described her decision as “My Medical Choice,” in an op-ed in the New York Times. She carries the BRCA1 gene mutation, which gives her an 87% risk of developing breast cancer at some point in her life. The abnormal gene also increases her risk of getting ovarian cancer, a typically aggressive disease, by 50%. To counteract those odds, Jolie wrote that she decided to have both her breasts removed. In 2010, Australian scientists found that women with the BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations who chose to have preventive mastectomies did not develop breast cancer over the three-year follow-up. Since the genetic abnormalities increase the risk of ovarian cancer, women who had their ovaries and fallopian tubes removed also dramatically lowered their risk of developing ovarian or breast cancers. The ability of medicine to predict one day, with relative certainty, the likelihood to develop certain conditions is an intriguing way, and leaves the open the possibility of ‘personalised medicine’ on the basis of your own individual information. If you think the NHS is already overstretched, with A&E closures contributing to the ‘crisis’ in emergency health provision, then footing a bill for personalised medicine might be the ‘straw that breaks the camel’s back’. The idea that one day you can predict the likelihood of a person developing multiple sclerosis or Alzheimer’s Disease still intrigues neurologists.

This furthermore presents formidable challenges for the law. In recent years, governments have been embracing policies that ‘nudge’ citizens into making decisions that are better for their own health and welfare, including our own Government which has decided to ‘mutualise’ its own ‘Nudge Unit’. The European Commission has embraced this ‘libertarian paternalism’ in its review of the Tobacco Products Directive. Various people has recently explained that by introducing measures such as plain packaging and display bans, the European Union may be able to ‘nudge’ people into smoking less, whilst preserving their right to choose. After having relied on the assumption that governments can only change people’s behaviour through rules and regulations, policy makers seem ready to design polices that better reflect how people really behave. Inspired by “libertarian paternalism,” the nudge approach suggests that the goal of public policy should be to steer citizens towards making positive decisions as individuals and for society while preserving individual choice.

It’s likely that a ‘one glove fits all’ policy is not going to work. About a decade ago, I was surrounded in my day job by individuals with hepatic cirrhosis, requiring abdominal paracentesis to tap away fluid from their tummies. And yet being confronted with people yellow due to the build-up of bilirubin did not deter me one jot from being a card-carrying alcohol. I am not over seventy months in recovery from alcohol misuse, so this aspect of how people make decisions before being addicted intrigues me. I think that people genuinely in addiction ‘can’t say stop’, as they don’t have an off-switch; they lack insight, and are in denial, mostly, I feel from personal experience.

It’s also clear that there is a long-list of medical problems that cause someone to present to an A&E department aside from alcohol, such as a sore-throat, faint, dislocated shoulder, and so on. But alcohol is undeniably a big issue, so the question is a sobering one, pardon the pun. To what extent can we ‘nudge’ people out of alcohol-related illness? Commenting on the report out today from the College of Emergency Medicine, that highlights the pressures that Accident and Emergency (A&E) wards are under, Dr John Middleton, Vice President for Policy at the Faculty of Public Health, said:

“We quite rightly have high expectations of doctors and nurses working in emergency medicine, so it’s only fair that they get the support they need to do their jobs safely and well. One way to reduce the burden on Accident and Emergency (A&E) wards would be to tackle the reasons why people are admitted in the first place: in particular, alcohol. Given that drink related violence accounts for over one million A&E visits every year, we urgently need the government to be bold and introduce a minimum price per unit of alcohol. That would reduce the burden on overstretched hospitals and society as a whole.”

Nobody likes assessing risk, especially the consequences of an addict picking up/using again are potentially catastrophic even if in probability terms theoretically infinitesimally low. People who know about Taleb’s “Black Swan” work will know this well. And assessing harm has led others to be blasted in the public arena previously, for example Prof David Nutt who once compared the dangers of horse riding to the dangers presented by the major drugs of abuse. At a time when both the medical and legal professions at least think there should be an open debate about having ‘another look’ at the Misuse of Drugs Act (1971), hopefully a public can welcome a mature debate on this.

Even today, the news reports that introducing a law to force cyclists to wear helmets may not reduce the number of hospital admissions for cycling-related head injuries. Researchers said that while helmets reduce head injuries and should be encouraged, the decrease in hospital admissions in Canada, where the law is in place in some regions, seems to have been “minimal”. The authors examined data concerning all 66,000 cycling-related injuries in Canada between 1994 and 2008 – 30% of which were head injuries. Writing in the British Medical Journal, the authors noted a substantial fall in the rate of hospital admissions among young people, particularly in regions where helmet legislation was in place, but they said that the fall was not found to be statistically significant.

I suppose all political parties desire people with capacity to make decisions about their own lifestyle and healthcare, very much in keeping with the ‘no decision about me without me’ philosophy currently in vogue. If push came to shove, if I could predict the future of my health, would I fundamentally change my behaviour? Probably within reason, but the only thing which I am pretty certain about is having another alcoholic drink may lead to a pattern of behaviour that will ultimately kill me.

So what of social enterprises and the NHS? Corporate social responsibility and marketing revisited.

Milton Friedman’s famous maxim goes as follows:

“there is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.”

The history of social enterprise in fact extends as far back to Victorian England (Dart, 2004; Hines, 2005). The worker cooperative is one of the first examples of a social enterprise. Social enterprises prevail through- out Europe, and are most notable in the form of social cooperatives, particularly in Italy, Spain and increasingly France (Mancino and Thomas, 2005).

More recently, Clare Gerada, the Chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners, yesterday on BBC’s “The Daily Politics”, stated the following:

“Privatisation is the moving of State resources into the for full profit or non-profit sectors. And – the previous debate is that ‘if you don’t pay for therefore it’s not privatisation – it is privatisation. The profit that Specsavers or Harmoni make, they will not go back into the State: they will go straight into the shareholders.”

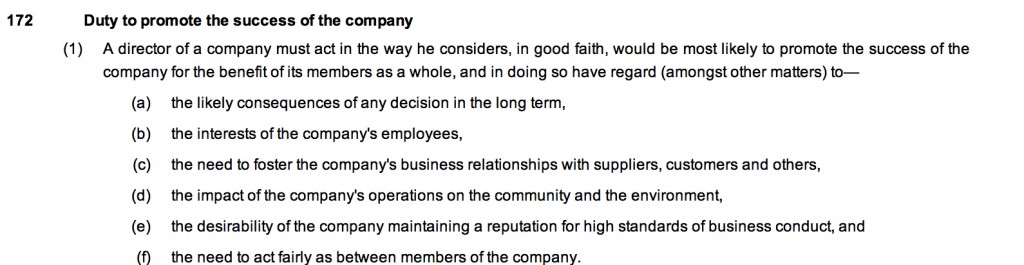

Currently, the position in English law is that the directors of every private limited company in law, whether they are called ‘social enterprises’ or not, have a statutory duty to the environment and stakeholders of their company. This is embodied in s.172 Companies Act (2006):

In an article by Rachel C. Tate, provocatively entitled, “Section 172 Companies Act 2006: the ticket to stakeholder value or simply tokenism?”, Tate argues as follows that stakeholder interests do not trump the interests of the company, i.e. to make profit. Interestingly. s.172 has no corollary in the common law.

“As highlighted, s172(1) formally obliges directors to consider stakeholder interests during the decision-making process. Yet, it is crucial to note that shareholder interests remain paramount. The interests of non-shareholding groups are to be considered only insofar as it is desirable to ‘(…) promote the success of the company for the benefit of its members.’17 A director will not be required to consider these factors beyond the point at which to do so would conflict with the overarching duty to promote company success. Stakeholder interests have no independent value in the consideration of a particular course of action.19 In addition, no separate duty or accountability is owed to the stakeholders included in the section.Thus, the duties of nurturing company success and having regard to the listed interests ‘(…) can be seen in a hierarchal way, with the former being regarded more highly than the latter.’21 Consequently, it would be wrong in principle to view s172 as requiring directors to ‘balance’ shareholders and stakeholder interests.22 These views are supported by industry guidance published on the effects of s172.”

“Social enterprises” are actually very hard to define. According to the United Kingdom (UK) government’s Department of Trade and Industry (2002), in the era of Tony Blair and Patricia Hewitt, a social enterprise is:

“a business with primarily social objectives whose surpluses are principally reinvested for that purpose in the business or in the community, rather than being driven by the need to maximise profit for shareholder and owners’”

Therefore, in theory, social ends and profit motives do not contradict each other, but rather have complementary outcomes, and constitute a ‘double bottom line’.

Nonetheless, the UK Government website contains a list of possible entities which could be described as ‘social enterprises’, namely:

- limited company

- charity, or from 2013, a charitable incorporated organisation (CIO is the new legal structure for charities)

- co-operative

- industrial and provident society

- community interest company (CIC)

- sole trader or business partnership

Note that in one of the vehicles, the limited company, as stated above, the primary duty of the directors is to promote success of the company. And that can be a “social enterprise”. Furthermore any contracts supplied to social enterprises can still still meet the definition of ‘privatisation’ above, not least because social enterprises are considered not to be wholly in the public sector (for example this EU definition, link here, where “Social enterprises are positioned between the traditional private and public sectors.”). Social enterprises do not meet the definition of what is typically in the public sector, by reference to the European System of Accounts 1995, link here. It is striking that the EU concede that one feature of social enterprises is a “significant level of risk”, so one has to question the long-term wisdom of competitive tendering contracts increasingly to social enterprises. Indeed, given that directors of English private limited companies are supposed to have due regard to wider “stakeholder” factors, one has to wonder quite what the point of the Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012 is. “Third Sector” magazine on 9 October 2012 reported that this enactment was not going that well:

“The Public Services (Social Value) Act could end up as a missed opportunity and more work needs to be done to encourage its use by commissioners and procurement professionals, delegates at the Labour Party conference heard. The act became law in March and places a duty on public bodies in England and Wales to consider “economic, social and environmental wellbeine in connection with public service contracts’! But at a fringe event hosted by the local infrastructure body Navca and the think tank ResPublica in Manchester, Hazel Blears, vice-chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Social Enterprise, said she was concerned that many local authorities would not give it the attention it deserved.”The wording is weak,”she said.”If they had to ‘take account of social value, that would have been a harder position.””

There has been concern that in social enterprises, whilst the external environment may be given prominence, the internal environment may suffer (Cornelius et al., 2008):

“Since many social enterprises exist predominantly to address social ends (one key feature of the triple bottom line), it could be argued that the prevalence of their CSR policy and practice require close investigation. Emanuele and Higgins (2000) con- tribute to this agenda by challenging the assumption that non-profit organisations can offer comparatively lower wages, because they are more pleasant places to work. The authors emphasise that employees in this sector are often second income earners, and therefore are less concerned with lower wages and reduced benefits more characteristic of the private sector. They highlight how the voluntary sector is often a job entry point for new employees, who later move on to other sectors offering more fringe benefits, better financial security and healthcare programmes. They conclude with the assertion that ‘‘we must begin to exert the same pressure for ‘corporate responsibility’ among non-profit employers, as we demand in the private sector’’ (Emanuele and Higgins, 2000: 92), implying that the social enterprise sector needs to treat its employees better. Distinguishing between external and internal CSR may be beneficial, with social enterprises clearly focusing upon serving communities and overlooking crucial internal human resource issues.”

Grimsby “Care Plus” has been, in fact, highly commended in the UK Social Enterprise Awards (link here). The national competition, organised by Social Enterprise UK, recognises excellence in Britain’s growing social enterprise sector. And yet it was recently reported that, “More than 800 staff employed by the Care Plus Group – which provides adult health and social care across North East Lincolnshire – are in consultation over cuts to their pay and conditions.” Lance Gardner, the Chief Executive of the organisation, is reported as saying, “There is a lot of goodwill here. Our staff go that extra mile for their patients and have a passion for caring. They would not want to see them suffer. I do not want to take our goodwill for granted.”

The story of what happened between UNISON and Circle Hinchingbrooke is of course well known now (link here):

“Christina McAnea, head of health at Unison, said Circle could “cream off nearly 50% of the hospital’s surpluses” which would make it “virtually impossible to balance the books”.

“This is a disgrace. Any surpluses should be going directly into improving patient care or paying off the hospital’s debt, securing its future for local people – not ploughed into making company profits.

“Instead patients and staff are facing drastic cuts. The hospital was already struggling, but the creep in of the profit motive means cuts will now be even deeper. And it is patients and staff that will pay the price.””

Of course, ‘corporate social responsibility’ (“CSR”), abbreviated to ‘people, planet, profit’ somewhat tritely, has clashed before with marketing, so it is no wonder that businesses should wish to look ‘socially responsible’ to seek competitive advantage. Corporates have long been criticised for using diversity as a marketing ploy, e.g. putting in their promotional literature photos of employees in wheelchairs to demonstrate they are disabled-friendly. Pitches from social enterprises are likely to come with them ‘a feel good factor’ in competitive tendering, and of course any pitch which complies with adding social value in keeping with the new legislation is perfect “rent-seeking” fodder. But at the end of the day they are a range of entities seeking to make money which does not necessarily get fed back into frontline care, but used to generate a surplus aka profit. In an outstanding essay by Anna Kim for the 8th Ashbridge Business School MBA award, the author writes:

“Many critics believe that most of so-called CSR activities are nothing but a deceptive marketing tool, such as greenwashing. Can British American Tobacco be a ‘responsible’ cigarette manufacturer? Is Nestle really moving towards social values, or simply trying to wash its image around the baby milk and other ethical issues by putting a Fairtrade label on its 0.2% of coffee product line? From the green policy of oil giants BP and Shell to the childhood obesity research fund of McDonald’s, the list of controversial CSR examples is not exhaustive.”

So what of social enterprises and the NHS – remember Milton Friedman and Clare Gerada….

References

Cornelius, N., Todres, M., Janjuha-Jivraj, J., Woods, A., and Wallace, J. (2008) Corporate Social Responsibility and the Social Enterprise, Journal of Business Ethics, 81, pp. 355–370.

Dart, R. (2004) The Legitimacy of Social Enterprise’, Nonprofit Management and Leadership ,14(Summer), pp. 411–424.

Department for Trade and Industry (2002) Social Enterprise: A Strategy for Success, available at http://www.seeewiki.co.uk/~wiki/images/5/5a/SE_Strategy_for_success.pdf .

Hines, F. (2005) Viable Social Enterprise – An Evaluation of Business Support to Social Enterprises’, Social Enterprise Journal, 1(1), pp. 13–28.

Mancino, A. and Thomas, A. (2005) An Italian Pattern of Social Enterprise: The Social Cooperative, Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 15(3), pp. 357–369.

We've just had a huge debate about the NHS. It's just a pity that it's been the wrong one.

Think of how much time we’ve just all spent, in thinking about the way in which services will be mostly put out for competitive tendering in the National Health Service. One of the first rules in law is that you fight your battles to the hilt, but, at first, you pick the right battles first. This is precisely what Labour appears not to have done. When Harriet Harman recently said on Question Time that the Conservatives are definitely not ‘to be trusted with the NHS’, Harriet curiously did not refer to the battle and war just won by the Conservatives (and Liberal Democrats) over NHS procurement. And yet the public desperately want Labour to stand up for the NHS. One member even suggested that, if Labour gave its unequivocal backing for restoring the NHS, Labour could even find itself with a massive vote winner.

Labour is clearly going through policy strands with a fine tooth comb, looking at, for example, the way in which multinational companies might employ workers at below the national minimum wage; effectively, controlling immigration through a wage policy. It does not appear to have worked out unequivocally whether it would reduce the rate of VAT, meaning possibly that the state borrowing requirement would temporarily increase. But do you see what they all did there? For days, weeks, or even months, we have been subjected to a relentless debate about EU immigration, when most surveys probably place the issue at number ten on the list of voters’ concerns. Unsurprisingly, the economy remains in ‘pole position’, but the ability of Labour to turn the opinion of the public, particularly in the South of England, away from the idea that Labour is ‘fiscally incontinent’ remains unconvincing. Labour is still considered to be the “tax and spend” party, for example, and Miliband appears painfully aware of that. So, when it comes to policy, there seems to be an odd combination of Labour shooting itself in the foot, or completely picking the wrong battles. And then you add in a complete inability to look at elephants in the room. Labour, to state the obvious, has no ability to implement any of its policies, if it is unable to win a General Election, and the confidence of Labour to win an election on its own is reflected accurately in Lord Adonis promoting his book that ‘if he were to form a new Lib-Lab pact, he wouldn’t start from here.‘

The NHS remains pivotal in Labour’s electoral chances, and Labour has been unable to use the resentment over the section 75 NHS regulations to maximise political capital. Why this should have happened in itself is interesting, as Andy Burnham, MP for Leigh, is a more than capable Shadow Secretary of State for Health. One of the issues is an ability to choose the right battle, possibly. Burnham, with some support from the right-wing media and thinktanks, has been banging on about integrated and whole-person care. Whether through conspiracy or cock-up, there will be short-term interest in how integrated care might be delivered. Think about a justification for State spending in the ‘mission impossible’ of implementing a NHS IT system. Why on earth would a right-wing libertarian government promote something which is national? Why on earth should you abort an ethos of ‘bonfire of the QUANGOs’ to introduce the biggest QUANGO in the country, viz NHS England? Whether you’re into conspiracy or cock-up, the integration of financial and medical information (including mental, physical and social care systems) allows for the perfect infrastructure for an insurance-based system. Insurance works on the basis of misrepresentation or non-disclosure to invalidate claims, so ‘big data’ serve a perfect storm for this. It won’t have escaped anybody’s attention that Labour (as indeed the Conservative Party) has been heading towards an insurance-based system for social care, so it does not require a massive ideological leap to think how this could be extended for all care with time. This does not involve any degree of paranoia, please note.

There is overwhelmingly an intellectual depravity in the bereft notion of producing policy through poll results and focus groups. New Labour clearly loved focus groups, with Philip Gould in ‘The Unfinished Revolution’ having devoted much airspace to developing a product in line with customers’ wishes. Of course, the Conservatives have a special affinity for polling organisations themselves, Nadhim Zadawi, in 2000 he co-founded YouGov and on its flotation became its CEO. YouGov is now one of the world leaders in political and business information gathering, polling and analysis. It employs over 400 staff on three continents and is listed on the London Stock Exchange. Again – it begs the question on why should Labour should wish to outdo the Conservatives on its own ability to use polling data? One of the polls which has become a toxic meme is how a high proportion of all voters would not mind who provides the NHS services, as long as it’s free at the point of use. However, this is intrinsically linked to other questions. Would you be prepared more in national insurance if it meant the NHS were able to provide a more comprehensive (universal) service?

It is indeed correct to state that the costs of renationalising the NHS might be overwhelming, although no accurate costings of this have ever been discussed properly. We do know, however, that the current cost of the NHS reorganisation is in the region of £3bn, but estimates of the actual cost inevitably have to be taken with a pinch of salt, as say the cost of Margaret Thatcher’s funeral. But to use this issue as a wish to stop discussion of this area is lazy, as one of the issues, as indeed as with Thatcher’s funeral, is that is this a sensible use of money compared to how it could be used elsewhere (so called “opportunity cost“)? Some people argue that the marketisation of the NHS has failed, in that any money spent on restoring a state-funded NHS would be money well spent. Restoring a state-funded service would get out of the idea of private companies being driven by maximising their profit margin, and not running a ‘more for less’ approach for delivering a service. Cynics might argue that the cost of restoring a state-run service is peanuts compared to waging a war abroad. Many remain unconvinced about the mantra that economic competition drives up quality, when it is the professional standards of healthcare staff, including doctors, nurses and allied health professionals, which appear to be at the heart of quality. The debate we have just had about the mode of procurement in the NHS was not one any of us as such elected; in other words, it has no mandate. If the Conservatives and the right-wing media appear so pre-occupied about having a referendum next parliament on our membership of the EU, many are (rightly) asking why Ed Miliband cannot ask for a mandate to take sensible decisions about the nature of the NHS. It is a given that there will always be a proportion of services which are outsourced to the private sector, but the question should be ‘how much’. Whilst a full-blown privatisation of the NHS has not happened yet, we have not even had a discussion of how much of the NHS should be outsourced.

And anyway Labour has to ask what really concerns all voters? In Mid Staffs and Cumbria, it is reported that there have been concerns about patient safety, and it may be mere coincidence that Labour failed to convince the voters in both places in the local elections over their offerings. However, there is certainly a ‘debate to be had’, about whether “efficiency savings” in the NHS are justified to produce surpluses in the NHS which get ploughed back into the Treasury (and therefore might be used for international overseas aid rather than frontline care.) Labour equally seems unable to look another ‘white elephant’ in the eye. That is of course the concept of a NHS hospital going bust. Should a NHS Trust which is in financial difficulty be simply allowed to go insolvent after a period of administration, or should the State pump money into it to maintain a local service to people in the community? This requires a fundamental reappraisal of how important “solidarity” and “social democracy” are, in fact, to Labour, and whether it wishes to use its extensive brand loyalty to have a mature, if sobering, discussion of the extent to which it wishes to fund a SOCIALIST National Health Service. Whilst in extremis it can be argued that a nostalgic return to ‘The Spirit of ’45” is not attainable, and is the wrong solution for the wrong times, there is a genuine perception that Labour has lost sight of its founding values. And why has this not been addressed in focus groups? It is well known that, in marketing, if you ask the wrong questions, you ubiquitously get the wrong answers.

Labour needs a mandate to confront these issues. And it should not be afraid to look for a resounding mandate, either. Whilst it might stick its fingers in its ears, and claim it’s nothing to do with them (arguing instead for integrated, “whole person” care), unless these ideological issues are confronted, NHS policy will continue to go down a right-wing path. For example, there is not much further to see GP ‘businesses’ being offered by the private sector, and the NHS pays for them; in this model, GP ‘businesses’ could operate under a standard 5-year contract, using NHS branding, under a ‘franchising’ model like Subway. And “The Tony Blair Dictum” is far from resolved, although currently there are issues more worthy of ‘firefighting’ in service delivery, such as the fiasco over ‘1111’. Labour’s problem is that it does not see the NHS as a ‘vote winner’, in the same way it doesn’t see the plight of disabled citizens experiencing difficulty with their benefits or people feeling genuinely threatened by ‘the bedroom tax’ as a top priority. Whilst Labour is unable to prioritise its issues in a way to align its aspirations with the concerns of the general public, there is no way on Earth it can hope to govern a convincing majority. If Labour wishes to learn a really useful trick from marketing, it could no better than to look at the ‘GAP analysis’ – looking at what the current situation is, and what the expectations of people are, and thinking how to get to a position of what people want. If people actually want a socialist universal, comprehensive NHS, paid for not in a private insurance system, Labour can be expected to work hard for a mandate to deliver this. If it doesn’t, that’s another matter, and it can witter on about whole-person care to its heart’s content.

It was honour to speak to a group of suspended Doctors on the Practitioner Health Programme this morning about recovery

It was a real honour and privilege to be invited to give a talk to a group of medical Doctors who were currently suspended on the GMC Medical Register this morning (in confidence). I gave a talk for about thirty minutes, and took questions afterwards. I have enormous affection for the medical profession in fact, having obtained a First at Cambridge in 1996, and also produced a seminal paper in dementia published in a leading journal as part of my Ph.D. there. I have had nothing to do with the medical profession for several years now, apart from volunteering part-time for two medical charities in London which I no longer do.

I currently think patient safety is paramount, and Doctors with addiction problems often do not realise the effect the negative impact of their addiction on their performance. No regulatory authority can do ‘outreach’, otherwise it would be there forever, in the same way that Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous do not actively go out looking for people with addiction problems. I personally have doubts about the notion of a ‘high functioning addict’, as the addict is virtually oblivious to all the distress and débris caused by their addiction; the impact on others is much worse than on the individual himself, who can lack insight and can be in denial. Insight is something that is best for others to judge.

However, I have now been in recovery for 72 months, with things having come to a head when I was admitted in August 2007 having had an epileptic seizure and asystolic cardiac arrest. Having woken up on the top floor of the Royal Free Hospital in pitch darkness, I had to cope with recovery from alcoholism (I have never been addicted to any other drugs), and newly-acquired physical disability. I in fact could neither walk nor talk. Nonetheless, I am happy as I live with my mum in Primrose Hill, have never had any regular salaried employment since my coma in the summer of 2007, received scholarships to do my MBA and legal training (otherwise my life would have become totally unsustainable financially apart from my disability living allowance which I use for my mobility and living). I am also very proud to have completed my Master of Law with a commendation in January 2011. My greatest achievement of all has been sustaining my recovery, and my talk went very well this morning.

The message I wished to impart that personal health and recovery is much more important than temporary abstinence, ‘getting the certificate’ and carrying on with your career if you have a genuine problem. People in any discipline will often not seek help for addiction, as they worry about their training record. Some will even not enlist with a G.P., in case the GP reports them to a regulatory authority. I discussed how I had a brilliant doctor-patient relationship with my own G.P. and how the support from the Solicitors Regulation Authority (who allowed me unconditionally to do the Legal Practice Course after an extensive due diligence) had been vital, but I also fielded questions on the potential impact of stigma of stigma in the regulatory process as a barrier-to-recovery.

I gave an extensive list of my own ‘support network’, which included my own G.P., psychiatrist, my mum, other family and friends, the Practitioner Health Programme, and ‘After Care’ at my local hospital.

The Practitioner Health Programme, supported by the General Medical Council, describes itself as follows:

The Practitioner Health Programme is a free, confidential service for doctors and dentists living in London who have mental or physical health concerns and/or addiction problems.

Any medical or dental practitioner can use the service, where they have

• A mental health or addiction concern (at any level of severity) and/or

• A physical health concern (where that concern may impact on the practitioner’s performance.)

I was asked which of these had helped me the most, which I thought was a very good question. I said that it was not necessarily the case that a bigger network was necessarily better, but it did need individuals to be open and truthful with you if things began to go wrong. It gave me a chance to outline the fundamental conundrum of recovery; it’s impossible to go into recovery on your own (for many this will mean going to A.A. or other meetings, and discussing recovery with close friends), but likewise the only person who can help you is yourself (no number of expensive ‘rehabs’ will on their own provide you with the ‘cure’.) This is of course a lifelong battle for me, and whilst I am very happy now as things have moved on for me, I hope I may at last help others who need help in a non-professional capacity.

Best wishes, Shibley

My talk [ edited ]

Competitive tendering is no longer the solution; it is very much the problem

As part of the “Big Society”, medics and lawyers have now been offended over competitive tendering. Competitive tendering is no longer the solution; it is very much the problem.

Yesterday, it was the lawyers’ turn. The Bar Standards Board (“BSB”) yesterday extended (10 May 2013) the first registration deadline for the Quality Assurance Scheme for Advocates in the face of a threatened mass boycott by barristers. The Solicitors Regulation Authority is expected to follow. In a statement yesterday, the BSB said the deadline will be extended from 10 January to 9 March 2014 ‘to ensure the criminal bar will have more time to consider the consequences of government changes to legal aid before registering’. The end of the first registration period will now be after the Ministry of Justice publishes its final response to its consultation on price-competitive tendering. The SRA board is expected to approve a similar extension later shortly.

A group of leading academics, including Prof. Richard Moorhead from University College London, indeed wrote yesterday,

“As academics engaged for many years in criminal justice research, we write to express our grave concern about the potentially devastating and irreversible consequences if the government’s plans to cut criminal legal aid and introduce a system of tendering based on price are introduced. Despite the claim by Chris Grayling, the minister of justice, that ‘access to justice should not be determined by your ability to pay’, this is precisely what these planned changes will achieve. This is not about ‘fat cat lawyers’ or the tiny minority of cases that attract very high fees. As we know from the experiences of people like Christopher Jefferies, anyone can find themself arrested for the most serious of crimes. No one is immune from the prospect of arrest and prosecution.”

Previously, it had been the medics’ turn. That did not deter Earl Howe in collaboration with people who clearly did not understand the legislation like Shirley Williams in competition with the medical Royal Colleges, Labour Peers and BMA. The Royal College of Physicians set out their oppositions to competitive tendering articulated their position last month:

Competitive tendering is often considered to promote competition, provide transparency and give all suppliers the opportunity to win business. It may be that price tags are driven down, but most reasonable professionals would actually ask, “At what cost?” Competitive tendering, rather, has a number of well known criticisms.

When making significant purchases, frank and open communication between potential supplier and customer is crucial. Competitive tendering is not conducive to open communication; in fact, it often discourages deep dialogue because in many cases all discussions between a bidder and the purchaser must be made available to all other bidders. Hence, Bidder A may avoid asking certain questions because the questions or answers may help other bidders by revealing Bidder A’s approaches, features, and the like. At the moment, there is a policy drive away from competition towards collaboration, innovation and ‘creating shared value’. Dr. Deming also writing in Out of the Crisis, “There is a bear-trap in the purchase of goods and services on the basis of price tag that people don’t talk about. To run the game of cost plus in industry a supplier offers a bid so low that he is almost sure to get the business. He gets it. The customer discovers that an engineering change is vital. The supplier is extremely obliging, but discovers that this change will double the cost of the items……the vendor comes out ahead.” This is called the cost-plus phenomenon.

Competitive tendering furthermore encourages the use of cheaper resources for delivering products and services. A supplier forced to play the competitive tendering game may come under pressure to keep costs down to ensure he gets a satisfactory profit margin. One way a supplier can lower costs is by using cheaper labour and/or materials. If the cheaper labour and materials are poor quality, the procurer will often end up with inferior, poor quality product or service. However, warranty and other claims may result –raising the price of the true, overall cost. Another area where suppliers may be tempted to lower costs is safety standards. This current administration is particularly keen on outsourcing, and sub-contractors may cut corners and creating safety risks. This is obviously on great concern where patient safety in the NHS has recently been criticised, after the Francis Inquiry over Mid Staffs NHS Foundation Trust. Furthermore, then government agencies, and indeed, private companies use competitive tendering it can take several years to choose a successful bidder, creating a very slow system. The result is the customer can wait incredibly long periods for product or service that may be required quickly. Finally, insufficient profit margin to allow for investment in research and development, new technology or equipment. Already, in the U.S., private “health maintenance organisations” spend as little as possible on national education and training of their workforce.

So the evidence is there. But, as the Queen’s Speech this week demonstrated on minimum alcohol pricing and cigarette packaging, this Government does not believe in evidence-based policy anyway. In the drive for efficiency, with a focus on price and cost in supply chains, the legal and medical professions have had policies imposed on them which totally ignores value. This is not only value in the product, but value in the people making the product. One only needs to refer to the (albeit extreme) example of a worker being retrieved from the rubble of that factory in Bangladesh to realise that working conditions are extremely important. This is all the more hideous since the policies behind the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act (2012) and the Health and Social Care Act (2012) were not in any of the party manifestos (sic) of the U.K. in 2010.

Competitive tendering is no longer the solution; it is very much the problem.

The Tories have never had any ideology, so it's not surprising they've run out of steam

A lot of mileage can be made out of the ‘story’ that the Coalition has “run out of steam”, and this week two commentators, Martin Kettle and Allegra Stratton, branded the Queen’s Speech as ‘the beginning of the end’. There is a story that blank cigarette packaging and minimum alcohol pricing policies have disappeared due to corporate lobbying, and one suspects that we will never get to the truth of this. The narrative has moved onto ‘immigration’, where people are again nervous. This taps into an on-running theme of the Conservatives arguing that people are “getting something for nothing”, but the Conservatives are unable to hold a moral prerogative on this whilst multinational companies within the global race are still able to base their operations using a tax efficient (or avoiding) base. Like it or now, the Conservatives have become known for being in the pockets of the Corporates, but not in the same way that the Conservatives still argue that the Unions held ‘the country to ransom’. Except things have moved on. The modern Conservative Party is said to be more corporatilist than Margaret Thatcher had ever wanted it to be, it is alleged, and this feeds in a different problem over the State narrative. The discussion of the State is no longer about having a smaller, more cost-effective State, but a greater concern that ‘we are selling off our best China’ (as indeed the late Earl of Stockton felt about the Thatcherite policy of privatisation while that was still in its infancy). The public do not actually feel that an outsourced state is preferable to a state with shared responsibility, as the public do not feel in control of liabilities, and this is bound to have public trust in privatisation operations (for example, G4s bidding for the probation service, when operationally it underperformed during the Olympics).

It is possibly this notion of the country selling off its assets, and has been doing so under all administrations in the U.K., that is one particular chicken that is yet to come home to roost. For example, the story that the Coalition had wished to push with the pending privatisation of Royal Mail is that this industry, if loss making, would not ‘show up’ on the UK’s balance sheet. There is of course a big problem here: what if Royal Mail could actually be made to run at a profit under the right managers? Labour in its wish to become elected in 1997 lost sight of its fundamental principles. Whether it is a socialist party or not is effectively an issue which seems to be gathering no momentum, but even under the days of Nye Bevan the aspiration of Labour was to become a paper with real social democratic clout. One of the biggest successes was to engulf Britain in a sense of solidarity and shared responsibility, taking the UK away from the privatised fragmented interests of primary care prior to the introduction of the NHS. The criticism of course is that Bevan could not have predicted this ‘infinite demand’ (either in the ageing population or technological advances), but simply outsource the whole lot as has happened in the Conservative-led Health and Social Act (2012) is an expedient short-term measure which strikes at the heart of poverty of aspiration. It is a fallacy that Labour cannot be relevant to the ‘working man’ any more, as the working man now in 2013 as he did in 1946 stands to benefit from a well-run comprehensive National Health Service. Even Cameron, in introducing his great reforms of the public sector in 2010/1 argued that he thought the idea that the public sector was not ‘wealth creating’ was nonsense, which he rapidly, unfortunately forgot, in the great NHS ‘sell off’.

The Conservatives have an ideology, which is perhaps outsourcing or privatisation, but basically it comes down to making money. The fundamental error in the Conservative philosophy, if there is one, is that the sum of individual aspiration is not the same as the value of collective solidarity and sharing of resources. This strikes to the heart of having a NHS where there are winners and losers, for example where the NHS can run a £2.4 bn surplus but there are still A&E departments shutting in major cities. Or why should we tolerate a system of ‘league tables’ of schools which can all too easily become a ‘race to the bottom’? Individual freedom is as relevant to the voter of Labour as it is to the voter of the Conservative Party, but if there is one party that can uphold this it is not the Conservatives or the Liberal Democrats. No-one on the Left can quite ignore why Baroness Williams chose to ignore the medical Royal Colleges, the RCN, the BMA or the legal advice/38 degrees so adamantly, although it does not take Brains of Britain to work out why certain other Peers voted as they did over the section 75 regulations as amended. But the reason that Labour is unable to lead convincingly on these issues, despite rehearsing well-exhausted mantra such as ‘we are the party of the NHS’, is that the general public received a lot of the same medicine from them as they did from the Conservatives or the Liberal Democrats. Elements of the public feel there is not much to go further; the Labour Party will still be the party of the NHS for some (despite having implemented PFI and NHS Foundation Trusts), and the Conservatives will still be party of fiscal responsibility for some (despite having sent the economy into orbit due to incompetent measures culminating in avoidance of a triple-dip).

It doesn’t seem that Labour is particularly up for discussion about much. It gets easily rumbled on what should be straightforward arms of policy. For example, Martha Kearney should have been doing a fairly uncontroversial set-piece interview with Ed Miliband in the local elections, except Miliband came across as a startled, overcaffeinated rabbit in headlights, and refused doggedly to explain why his policy would not involve more borrowing (even when Ed Balls had said clearly it would.) Miliband is chained to his guilty pleasures of being perceived as the figurehead of a ‘tax and spend’ party, which is why you will never hear of him talking for a rise in corporation tax or taxing excessively millionaires (though he does wish to introduce the 50p rate, which Labour had not done for the majority of its actual period in government). It uses terms such as “predistribution” as a figleaf for not doing what many Labour voters would actually like him to do. Labour is going through the motions of receiving feedback on NHS policy, but the actual grassroots experience is that it is actually incredibly difficult for the Labour Party machine even to acknowledge actually well-meant contributions from specialists. The Labour Party, most worryingly, does not seem to understand its real problem for not standing up for the rights of workers. This should be at the heart of ‘collective responsibility’, and a way of making Unions relevant to both the public and private sector. Whilst it continues to ignore the rights of workers, in an employment court of law over unfair dismissal or otherwise, Labour will have no ‘unique selling proposition’ compared to any of the other parties.

Likewise, Labour, like the Liberal Democrats, seems to be utterly disingenious about what it chooses to support. While it seems to oppose Workfare, it seems perfectly happy to vote with the Government for minimal concessions. It opposes the Bedroom Tax, and says it wants to repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2012), but whether it does actually does so is far from certain; for example, Labour did not reverse marketisation in the NHS post-1997, and conversely accelerated it (admittedly not as fast as post-2012). No-one would be surprised if Ed Miliband goes into ‘copycat’ mode over immigration, and ends up supporting a referendum. This could be that Ed Miliband does not care about setting the agenda for what he wants to do, or simply has no control of it through a highly biased media against Labour.

Essentially part of the reason that the Conservatives have ‘run out of steam’ is that they’ve run out of sectors of the population to alienate (whether that includes legal aid lawyers or GPs), or run out of things to flog off to the private sector (such as Circle, Serco, or Virgin). All this puts Labour in a highly precarious position of having to decide whether it wishes to stop yet more drifting into the private sector, or having to face an unpalatable truth (perhaps) that it is financially impossible to buy back these industries into the public sector (and to make them operate at a profit). However, the status quo is a mess. The railway industry is a fragmented disaster, with inflated prices, stakeholders managing to cherrypick the products they wish to sell to maximise their profit, with no underlying national direction. That is exactly the same mess as we have for privatised electricity, or privatised telecoms. That is exactly same mess as we will have for Royal Mail and the NHS. The whole thing is a catastrophic fiasco, and no mainstream party has the bottle to say so. The Liberal Democrats were the future once, with Nick Clegg promising to undo the culture of ‘broken promises’ before he reneged on his tuition fees pledge. UKIP are the future now, as they wish to get enough votes to have a say; despite the fact they currently do not have any MPs, if they continue to get substantial airtime from all media outlets (in a way that the NHS Action Party can only dream of), the public in their wisdom might force the Conservatives or Labour to go into coalition with UKIP. There is clearly much more to politics than our membership of Europe, and, while the media fails to cover adequately the destruction of legal aid or the privatisation of the NHS, the quality of our debate about national issues will continue to be poor. Ed Miliband must now focus all of his resources into producing a sustainable plan to govern for a decade, the beginning of which will involve an element of ‘crisis management‘ for a stagnant economy at the beginning. The general public have incredibly short memories, and, although it has become very un-politically correct to say so, their short-termism and thirst for quick remedies has led to this mess. Ed Miliband seems to be capable of jumping onto bandwagons, such as over press regulation, but he needs to be cautious about the intricacies of policy, some of which does not require on a precise analysis of the nation’s finances at the time of 7th May 2015. With no end as yet in sight for Jon Cruddas’ in-depth policy review, and for nothing as yet effectively Labour to campaign on solidly, there is no danger of that.

Why the National Health Action Party doesn't need its own 'Country Club Bore'

There is apparently a consensus around Westminster circles that Nigel Farage is ‘the Country Club bore’, a slightly red-faced jovial, charismatic man who doesn’t particularly mind speaking shit.

While such people appear pleasant, often their messages are not entirely trivial. The same criticism has been made of ‘Bungling Bojo’ i.e. Boris Johnson, that behind the buffoonery there is quite an incisive mind who politically astute. The Left, which has been accused previously of lacking a sense of humour by notorious funnyman Jeremy Clarkson, appears not to have its own ‘nice buffoon’. Maybe it’s because buffoons are supposed to have posh accents and smile a lot – though Tony Blair did have a posh accent, and smile a lot.

UKIP policies simply don’t add up. I have previously thought that UKIP could equally appeal to the left, in that Labour also has a proud history of wishing to leave Europe. The recent accusation that ‘UKIP means “racists for posh people” has been violently criticised by UKIP who cite that the last thing that they are are racist (either even having members from ethnic minorities themselves, or having members who are married to people from abroad.) They don’t have a single MP, and yet they are given a huge amount of air time. People often joke on Twitter that tonight it is ‘Nigel Farage Nigel Farage Nigel Farage Nigel Farage Nigel Farage #BBCQT”.

Emulating the secret of Nigel Farage is, though, difficult if you’re a “single issue party”. Nigel Farage is very different to Caroline Lucas, or Natalie Bennett. One suspects you would never get Nigel Farage voting against the section 75 NHS regulations, even though one also suspects that Farage wouldn’t know what these regulations are even if his life depended on them. However, Nigel Farage has been an effective ‘Trojan horse’ for getting his immigration issues a lot of air time. The National Health Action Party would probably love to have the media dominance which has been secured by UKIP, but the last thing the National Health Action Party needs at this time their own equivalent of a ‘Country Club Bore’.

However, the National Health Action Party, I feel, should think carefully about what sort of impression they wish to create. There is a huge amount of goodwill and affection to the NHS from traditional voters of all parties, and Dr Clive Peedell and Dr Richard Taylor could not do much worse than to present themselves as a modern day Alec Douglas-Home. The patrician view of the NHS consultant, who spends most of his time on the golf course (which is of course completely untrue), would go down like a lead balloon with the electorate.

Also, it has a very serious dialogue to have with the electorate, on the future of the NHS, who “owns it”, who it “works for”, and who is deciding policy for it. The enactment of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) was one of the most disastrous steps to increase the democratic deficit ever to take place in England, when it became clear that this current Government is much more interested in having behind-closed-doors conversations with private healthcare providers than members of the medical Royal Colleges or the BMA, for example. Sure, the the National Health Action Party needs to represent faithfully the views of all healthcare professionals including nurses, as well as Doctors, but it also needs to represent ordinary members of the general public. Dressing up in theatre scrubs or donning a medical stethoscope, akin to a low-budget RAG project, may not be the best way to project a serious image, but the election in Eastleigh was a real eye-opener in how the media could completely ignore NHS issues.

Whilst it is tempting to spend a lot of time and energy in wondering why the BBC have steadfastly refused to cover the NHS reforms, to be frank the discussion of the NHS’ journey of late has been scant and pathetic for a very long time. Members of the public are generally aware of the private finance initiative, but seem generally unaware of the major advances in this initiative during Major’s short stay in government. Likewise, people are generally unaware of the impact of NHS Foundation Trusts, what ‘efficiency savings’ are, or what the failure regimes of NHS hospitals means. The social media can do so much, and it is incredibly disheartening to hear Liberal Democrats whining in the House of Lords about how much ‘misinformation’ has emerged from the social media.

The basic issue is that the social media is the only mechanism many people have for discussing the NHS at all, and neutering this device is in nobody’s interest apart from powerful corporates. While the National Health Action Party may not have its equivalent of the “Country Club bore”, I am sure that they are putting maximum effort into thinking which seats they wish to target, what their core message is, what they feel the basic understanding of voters on issues to do with the NHS might be, how they’re going to get their message across, and what they feel their ideal outcome is. I think they should drag themselves away from the philosophy of the ‘focus group’ made popular by New Labour, but lead on what they think is right. This could include populist issues, of massive public policy concern, such as patient safety, which no traditional party has had a moral licence to pursue.

The Bangladeshi fire explains why Tony Blair's view of the NHS market is wrong

I am doing a Dan Hodges. But this time it is against his ideological pin-up Tony Blair, who knew the price of everything but the value of nothing. He was the future once, but now is not the time for clichés.

Tony Blair once said, ‘I don’t care who is providing my NHS services, as long as they are the most efficient’. He would, had his views been alive and relevant today, might equally have been applied to competitive tendering in the legal services sector. That sector too has also seen an ethos where profit rules; in a weird Darwinian ‘survival of the fitness’, human rights cases of massive social importance such as in housing or asylum are considered the lowest caste, compared to share acquisition of a multinational corporate. This is the attitude of anyone who would rather sell their own grandmother, than to look to a sustainable future.

“I don’t care who makes my T shirt as long as it’s the cheapest.” I would be very surprised if Primark and Matalan suffer a massive loss of trade as a result of public reaction to the collapsing sweatshop in Bangladesh. The similarity with the Texas fertiliser explosion is that there is no such thing as protection for workers by the Unions. Any country which has been trying to water down or to make workers’ rights non-existent, in the name of ‘industrial relations’, should think twice about whether they deserve to be called ‘a civilised country’. In this era of a maximum number of underemployed people with non-existent employment rights, and corporates making a killing weathering the recession, the public have to think: whose side is the government actually on?

ATOS are still achieving millions of profits, even though it is widely reported that administration of welfare benefits has caused immense mental distress as they have been do badly done; hence talk of why people cannot record their own assessment interviews as legal evidence, and the proportion of decisions made by ATOS which are overturned by the law courts on appeal. Add to that the staggering reports of people committing suicide because of their welfare benefits decisions (where it is incredibly difficult to prove causality); nonetheless, there is now a growing case of a link between mental illness and government policies of austerity in many jurisdictions.

Does it matter that the world has no morals but makes money? It does depend on your point-of-view, but will impact upon whether you feel that a leading sugary soft drinks multinational should be advising the current Obama administration on obesity. The building collapsing in Dhaka, and the subsequent fire, has brought out much disgust, which occasionally hits the mainstream media. But it all subsides again – attempts have been made to revisit history, so you will never find a clear account of the Bhopal explosion of the Union Carbide plant.

This issue of ‘corporate social responsibility’ has been advanced most prominently by Prof Michael Porter at Harvard, and emphasises that corporates living as responsible members of society is not simply a matter of marketing and PR but extremely important for society. Broadly speaking, proponents of corporate social responsibility have used four arguments to make their case: moral obligation, sustainability, license to operate, and reputation. “Reputation” is odd when applied to the current NHS, because, despite efforts by the King’s Fund and the current Tory-led government, attempts at making the NHS ‘consumerist’ have largely been overwhelmingly unsuccessful. Porter, in Harvard Business Review in October 2006, wrote: “In stigmatized (sic) industries, such as chemicals and energy, a company may instead pursue social responsibility initiatives as a form of insurance, in the hope that its reputation for social consciousness will temper public criticism in the event of a crisis. This rationale once again risks confusing public relations with social and business results.”

Legally, private limited companies have a duty for their directors to promote the ‘success’ of the company, i.e. profitability in the narrowest sense, under the Companies Act (1996). The idea of improved competition driving quality is strangled at birth by the fact that imperfect markets do nothing but encourage collusive behaviour in pricing, little choice in product, and massive profits for the shareholders. The concomitant ‘improvement’ in quality is barely noticeable. This has been the consistent outcome of all the privatisations in England, such as gas, water, electricity, and telecoms, where the consumer has suffered in an overpriced, fragmented service; Royal Mail will be next.

The Bangladeshi Fire is a human tragedy of unfathomable proportions, and is entirely driven by a consumerist culture where people appear do not care how the product arrives on the table, so long as it is there most ‘efficiently’. Of course, employment laws are there to protect the welfare of T-shirt makers, but this is what the Conservative government call ‘unnecessary red tape’ when applied in this country. The fire also poses serious questions about how we do business while Cameron pursues his ‘global race’. If Britain is not careful, it can easily outsource functions to abroad, and make as much of them as cheaply as possible. Diagnosis of dementia could be through an automated innovated server in Thailand, delivered by a multinational, with its head office in one of the Channel Islands to avoid tax maximally, to deliver healthy private equity profits. While it may not be the Unions that hold the country ‘to ransom’ any more, the power behind closed doors of private equity and bankers is not to be underestimated in the pursuit of profit.

Before going down the commodification of healthcare and the “Tony Blair dictum”, spend one moment thinking about exploding fertiliser plants in Texas or buildings collapsing in Bangladesh, as the lessons for business there could be salient for our increasingly privatised National Health Service (achieved entirely undemocratically.)