Home » Posts tagged 'Tony Blair dictum'

Tag Archives: Tony Blair dictum

Tony Blair’s NHS market and T-shirts in Bangladesh

I am doing a Dan Hodges. But this time it is against his ideological pin-up Tony Blair, who knew the price of everything but the value of nothing. He was the future once, but now is not the time for clichés.

Tony Blair once said, ‘I don’t care who is providing my NHS services, as long as they are the most efficient’. Had his views been alive and relevant today, they might equally have been applied to competitive tendering in the legal services sector. That sector too has also seen an ethos where profit rules; in a weird Darwinian ‘survival of the fitness’, human rights cases of massive social importance such as in housing or asylum are considered the lowest caste, compared to share acquisition of a multinational corporate. This is the attitude of anyone who would rather sell their own grandmother, than to look to a sustainable future.

“I don’t care who makes my T shirt as long as it’s the cheapest.” I would be very surprised if Primark and Matalan suffer a massive loss of trade as a result of public reaction to the collapsing sweatshop in Bangladesh. The similarity with the Texas fertiliser explosion is that there is no such thing as protection for workers by the Unions. Any country which has been trying to water down or to make workers’ rights non-existent, in the name of ‘industrial relations’, should think twice about whether they deserve to be called ‘a civilised country’. In this era of a maximum number of underemployed people with non-existent employment rights, and corporates making a killing weathering the recession, the public have to think: whose side is the government actually on?

ATOS are still achieving millions of profits, even though it is widely reported that administration of welfare benefits has caused immense mental distress as they have been do badly done; hence talk of why people cannot record their own assessment interviews as legal evidence, and the proportion of decisions made by ATOS which are overturned by the law courts on appeal. Add to that the staggering reports of people committing suicide because of their welfare benefits decisions (where it is incredibly difficult to prove causality); nonetheless, there is now a growing case of a link between mental illness and government policies of austerity in many jurisdictions.

Does it matter that the world has no morals but makes money? It does depend on your point-of-view, but will impact upon whether you feel that a leading sugary soft drinks multinational should be advising the current Obama administration on obesity. The building collapsing in Dhaka, and the subsequent fire, has brought out much disgust, which occasionally hits the mainstream media. But it all subsides again – attempts have been made to revisit history, so you will never find a clear account of the Bhopal explosion of the Union Carbide plant.

This issue of ‘corporate social responsibility‘ has been advanced most prominently by Prof Michael Porter at Harvard, and emphasises that corporates living as responsible members of society is not simply a matter of marketing and PR but extremely important for society. Broadly speaking, proponents of corporate social responsibility have used four arguments to make their case: moral obligation, sustainability, license to operate, and reputation. “Reputation” is odd when applied to the current NHS, because, despite efforts by the King’s Fund and the current Tory-led government, attempts at making the NHS ‘consumerist’ have been overwhelmingly unsuccessful. Porter, in Harvard Business Review in October 2006, wrote: “In stigmatized (sic) industries, such as chemicals and energy, a company may instead pursue social responsibility initiatives as a form of insurance, in the hope that its reputation for social consciousness will temper public criticism in the event of a crisis. This rationale once again risks confusing public relations with social and business results.”

Legally, private limited companies have a duty for their directors to promote the ‘success’ of the company, i.e. profitability in the narrowest sense, under the Companies Act (1996). The idea of improved competition driving quality is strangled at birth by the fact that imperfect markets do nothing but encourage collusive behaviour in pricing, little choice in product, and massive profits for the shareholders. The concomitant ‘improvement’ in quality is barely noticeable. This has been the consistent outcome of all the privatisations in England, such as gas, water, electricity, and telecoms, where the consumer has suffered in an overpriced, fragmented service; Royal Mail will be next.

The Bangladeshi Fire is a human tragedy of unfathomable proportions, and is entirely driven by a consumerist culture where people appear do not care how the product arrives on the table, so long as it is there most ‘efficiently’. Of course, employment laws are there to protect the welfare of T-shirt makers, but this is what the Conservative government call ‘unnecessary red tape’ when applied in this country. The fire also poses serious questions about how we do business while Cameron pursues his ‘global race’. If Britain is not careful, it can easily outsource functions to abroad, and make as much of them as cheaply as possible. Diagnosis of dementia could be through an automated innovated server in Thailand, delivered by a multinational, with its head office in one of the Channel Islands to avoid tax maximally, to deliver healthy private equity profits. While it may not be the Unions that hold the country ‘to ransom’ any more, the power behind closed doors of private equity and bankers is not to be underestimated in the pursuit of profit.

Before going down the commodification of healthcare and the “Tony Blair dictum”, spend one moment thinking about exploding fertiliser plants in Texas or buildings collapsing in Bangladesh, as the lessons for business there could be salient for our increasingly privatised National Health Service (achieved entirely undemocratically.)

The “Tony Blair dictum” (revisited)

Labour themselves perhaps wished to “open up” the NHS to more private sector involvement, even if they did not “introduce” the private market approach to the NHS: it is felt by many that was successfully achieved in the 1980s under the previous Thatcher administration. More recently, the details of “independent sector treatment centres”, and criticisms about their relative inefficiency, introduced under the previous Labour administration are well known.

A Future Fair For All?

Indeed, Labour’s 2010 general election manifesto promised:

“We will support an active role for the independent sector working alongside the NHS in the provision of care, particularly where they bring innovation – such as in end-oflife care and cancer services, and increase capacity”

and further promised that:

“patients requiring elective care will have the right, in law, to choose from any provider who meets NHS standards of quality at NHS costs.”

The “Tony Blair Dictum”

The “Tony Blair dictum” essentially is that it doesn’t matter who provides care, so long as it is free to the patient. It approaches the perspective of a ‘reasonable member of the general public’ as somebody who does not particularly care how much his or her own personal healthcare services is costing the taxpayer “or increasing the deficit”. It is therefore quite a Thatcherite view of an individual, rather than a view held by a socialist.

This is an extract from a speech given by Rt Hon Tony Blair MP, The Prime Minister to a meeting of The New Health Network Clinician Forum on Tuesday 18th April 2006:

“…

Therefore thirdly, patients are being given a choice of NHS provider. So if they have to wait too long at one hospital or are dissatisfied with the standard of care, they can go elsewhere. This choice is already available in the private sector. Now it will be available in the NHS.

Fourth, there will be new independent providers encouraged in the NHS, of which the ITC’s are the first wave. Now this is being opened up to diagnostics, where the major bottlenecks often occur. In addition, where GP lists are full and areas are underprovided, new providers will, for the first time ever, be allowed to come in and provide GP services.

As a consequence of these reforms, there is then structural change to Strategic Health Authorities and PCTs, to streamline them so that they fit the purpose of a less centralised system and to focus them on helping the effective commissioning of care

The result of all of this is to try to create an NHS where there is not a market in the sense that consumer choice is based on an individual user’s wealth; but where there is the opportunity, on an equal basis, for users to choose and exercise power over the system that provides the service. It signals the move from a “get what you’re given” service where the patient falls into line with what the service decides; to one that is more a “get what you want” service moulded around the decisions of the patient. It rewards the producers well; but insists in return that it is the user that comes first. It mirrors the change from mass production to a customised service in the private sector.”

Sean Worth only this week at the RSA used this patient choice argument to justify the enactment of new legislation, “putting patients’ voices in control” and “public’s choices driving policies, not politicians in backroom deals.”

The overall intellectual property legislative framework for branding for “independent sector treatment centres” in this regard is very interesting. In English law, branding is protected by registered trademarks, such that goodwill to and the reputation of the organisation is protected. The branding is meant to be “shop window” of an organisation, and represents the “badge of origin”. In the NHS’ case, co-branding private providers’ suppliers brands with the NHS logo sets out a rather confusing message about the exact origin of NHS services which have been made available by private suppliers. It cannot be the case the “ethos” of private suppliers is the same as that of the NHS, in that private limited companies exist in law for the directors to maximise shareholder dividend.

In this particular context, the branding advice is very specific, for instance:

Remember: you cannot use the NHS logo on any materials which are not directly related to the provision of your NHS services. For all marketing materials that are co-branded with the NHS logo, you must use theNHS typefaces and colour palette.Your marketing materials must also support the NHS brand values and communication principles.

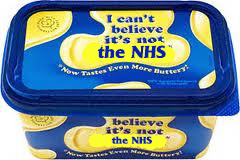

“I can’t believe it’s not the NHS”

Therefore, it seems that, at face value, the Coalition like the previous administration is allowing the patient to ‘shop around’ for the NHS services, and these NHS services are being made available.

THERE ARE MASSIVE ECONOMIC PROBLEMS WITH THE TONY BLAIR DICTUM, RECYCLED BY SEAN WORTH ABOVE.

Fundamental difficulties still arise from this type of scenario, and they’re all to do with information. Tim Kelsey and Paul Nuki might argue that “the more information the better”, but there are still significant policy issues here.

If the information cost of services is made available to the patient, then the accusation will come that patients are ultimately choosing their services on the basis of low cost not high quality; and furthermore the patient will simply get confused in trying to reconcile this with clinical advice from his or her own GP; and thirdly there is potentially a conflict-of-interest anyway between the Doctor and his/her patient about clinical need and cost.

If this information is not made available to the patient, then it is perfectly possible that a single provider can decide to become known for a certain procedure such as day case hernias, which just happens to be “low cost and high volume”. and this is where the problem of “cherry picking” comes in. It is perfectly possible for the private provider then to make a huge profit from such procedures, unknown to the taxpayer who is ultimately paying for these, as long as these private providers are awarded contracts (by submitting slick pitches on the basis of “integrated care” or “best value”). Tthe private provider is of course very happy because it can return a massive shareholder dividend to its investors, and in the long term the costs of running the NHS get much larger.

This is precisely what has happened in all other privatised industries, such as gas, electricity, telecoms, water, leading to a fragmented service, offering homogenous products where there is massive supplier strength in a crowded market (an “oligopoly”), where in fact there is little real competition. The idea of choice, in shopping in a supermarket or even in a patient choosing a NHS standard service, is fine IF the market is not distorted. Instead, an ability of a NHS patient to shop around will then be an artifact of how crowded the market is, and how much a clinical commissioning group will justify clinical decisions with the risk of facing expensive litigation suits in domestic and EU courts of law (which Monitor cannot protect them from, now that the NHS section 75 Regulations have finally been drafted officially.)

There is a huge problem with all of this. The biggest danger still remains about how, if left to its own devices, the market can steer to becoming contracted, which is why it is hardly surprising that the statutory duty of the Secretary of State to provide comprehensive healthcare has been removed, even if what remains strictly speaking remains “free-at-the-point-of-use”. That’s why politicians have become very adept at separating “universal” or “comprehensive”, from the “free-at-the-point-of-use” strands.

Therefore this little tub of “I can’t believe it’s not the NHS” may not be as innocuous as it first appears. The issue is of course the extent to which parliament wishes to throw the NHS to the private sector. However, this Government have made it very clear that their statutory instruments lock the NHS into a private competitive market unless in extreme conditions, paving the way for the destruction of the infrastructure of the NHS, as Oliver Letwin’s alleged remark, “The NHS will not exist any more”, can tragically become true.

Thank you very much for valuable comments on previous drafts of this article.