Home » Posts tagged 'speak out safely'

Tag Archives: speak out safely

Why speaking out safely and safe staffing are important moral issues for the NHS

A culture where staff and patients can speak openly about successes and failures in the NHS, as well as more specifically on safe staffing issues, is essential for the NHS to move forward. Perhaps most intriguingly, the failure of the English law to cherish the need to ‘speak out safely’ in the NHS can be tracked back to four Acts of parliament ranging in the last thirty years uptil the present day.

A culture where staff and patients can speak openly about successes and failures in the NHS, as well as more specifically on safe staffing issues, is essential for the NHS to move forward. Perhaps most intriguingly, the failure of the English law to cherish the need to ‘speak out safely’ in the NHS can be tracked back to four Acts of parliament ranging in the last thirty years uptil the present day.

The focus recently has tended to be about whether things would or would not work, and have either been economic or regulatory in perspective.

The Health and Social Care Act (2012), all 493 pages of it, is fundamentally a statutory instrument which proposes the mechanism for competitive tendering in the NHS (through the now infamous section 75), the financial failure regimes, and the regulatory mechanisms to oversee an emboldened market. It is therefore a gift for the corporate lawyers. It does, though, successfully mandate in law the abolition of the National Patient Safety Agency in s. 281.

There is therefore not a single clause on patient safety in this voluminous document. Patients, and the workforce of the NHS, are however at the heart of the NHS.

The language has been overridden by economic concepts misapplied. “Sustainability” is a very good example. Too often, sustainability has been used as a synonym for ‘maintained’, usually as a precursor for an argument about shutting down NHS services. It quite clearly from the management literature means a future plan of an entity with due regard to its whole environment.

Discussion about regulators can lead to a paralysis of policy.

No sanctions against Doctors have yet been made by the GMC over Mid Staffs, which does rather appear to be a curious paradox given the widespread admissions of undeniably ‘substandard care’. The regulator needs to have the confidence of the public too. One of their rôles is commonly cited to be to ‘protect the public‘, and this is indeed enshrined in law under s.1(1A) Medical Act (1983).

It is of regulatory interest how precisely the GMC ‘protected the public’ over Mid Staffs, whatever the operational justifications of their legal processes in this particular case.

Strictly speaking, promoting the safety of the public might include promoting the ability of clinical staff ‘to speak out safely’, and this could be an important manifestation of a core legal objective of that particular regulator?

On the other hand, confidence in the regulator is never achieved by any regulator on the basis of conducting “show trials“. This can be always be a big danger, as GMC cases on occasions attract wider general media interest. This will, of course, be to the detriment of defendants with complicated mental health issues.

There is little fundamental dispute about the need for clinicians to be open about medical errors in their line of work. Even the Compensation Act (2006), if you need to cite the law, provides that an apology does not mean an admission of liability in section 2.

There can be disputes about upon whom the ‘duty of candour’ should fall, whether this might be the Trust or an individual clinician, and who is going to enforce it.

But just because there are legal issues about the practicality of it, a civilised society must use the law to reflect the society it wishes for.

There is currently, for example, a statutory duty for company directors to maximise shareholder dividend of a company with due regard to the environment (as per s.172 Companies Act (2006)). There is no corresponding duty for hospitals to minimise morbidity or mortality on their watch.

“Whistleblowers” are often accused of raising their complaints too late.

Whistleblowers can find themselves becoming alien for NHS organisations they are devoted to.

Often, there is a ‘clipboard mentality’ where ‘colleagues’ will raise issues to discredit the whistleblowers. Often these ‘colleagues’ are protecting their own back. Regulators should not collude in such initiatives.

And yet it is clear that the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998 fails both patients and whistleblowers.

There are ways to bring about change. Most often regulation is not in fact the answer.

A cultural change is definitely needed, and this appears to go beyond corrective mechanisms through English jurisprudence.

This in the alternative requires staff and patients from within the NHS prioritising speaking out safely.

The information which can be provided by ‘speaking out safely’ should be treated like gold dust – and be used for improvement for patient safety in the NHS, as well as in the performance management of all clinicians involved.

Arguably the precise information is much more useful than an estimate such as the ‘hospital standardised mortality ratio’ which does not operate on a case-by-case basis anyway.

A new-found desire to speak openly might also include a wider policy discussion about safe staffing levels. Regulating a minimum staffing level might shut down important debates about ‘what is safe’, such as the skill mix etc. And yet there are equally important issues about how to prioritise this in the law.

The hypothesis that unsafe staffing levels or poor resources generally lead to poor patient safety in some foci of the NHS has not been rejected yet. It’s essential that managers allow staff to be listened to, if they have genuine concerns. Not everything is vexatious.

Most of all, society has to be seen to reward those people who have been strong in putting the patient first.

Small steps such as Trusts in England supporting the Nursing Times’ “Speak Out Safely” campaign are important.

Critically, such support is vital, whatever political ideology you hail from.

It could well be that the parliamentary draftsmen produce a disruptive innovation in jurisprudence, such that speaking out safely is correctly valued in the English law, and thenceforth in the behaviour of the NHS.

Hopefully, an initial move with the recent drafting of a clause of the “legal duty of candour” in the Care Bill (2013) we will begin to see a fundamental change in approach at last.

On NHS patient safety: the silence of the lambs is coming to an end

Defamatory comments about any of these whistleblowers will from now be on reported to the Police. The Socialist Health Association is keeping a careful record of the IP addresses of these comments which have been made thus far.

Look at what happened in the biggest financial scandal ever to hit the United States. Driven by profit, company directors in ENRON turned a complete blind-eye to criminal fraudulent activity. They had a healthy relationship with the US government, which they wanted to impress. The shock waves from the ENRON scandal are felt still all around the world, and in the end the US had to legislate the Sarbanes-Oxley Act which does indeed contain provisions on ‘whistleblowing’. The NHS situation is quite different, in that there is much wonderful, safe, work done by brilliant clinicians. Not all managers deserve their demonisation by any stretch of the imagination. The report by Prof Don Berwick is the latest in the long line of reports on Mid Staffs, but this one has yet further emphasised the critical need for patient engagement. Berwick’s committee specifically say that this should not simply be seen as a ‘seen-to-be-engaging’ sop for patients – it is real involvement by patients in guiding policy. For those who wish to ‘cure’ the NHS, there is a real sense that patients are not being listened to, and at worst mistakes are being ‘covered up’. I feel there is now emerging a dual duty of the NHS – one of safety for the patient, and one of safety for its staff. I have long urged the NHS to deal with the mental welfare of its workforce, and to acknowledge the soul-destroying effects of making to work in an environment of fewer staff for greater ‘productivity’. But the two are linked. That’s why the “Nursing Times Speak Out Safely” [@NursingTimesSOS] campaign has a very important part to play now.

[They] want:

- The government to introduce a statutory duty of candour compelling health professionals and managers to be open about care failings

- Trusts to add specific protection for staff raising concerns to their whistleblowing policies

- The government to undertake a wholesale review of the Public Interest Disclosure Act, to ensure whistleblowers are fully protected.

It is all too easy to denigrate the entire workforce of the NHS including frontline staff and managers, but, across a number of different sectors, toxic cultures have bred a hostile, pessimistic workforce, driven away top talent and prevented organisations from reaching their full potential. While toxic work cultures are the end result of many factors, poor leadership has a big part to play. The fuel for toxic work environments is typically a combination of conflict, ego, gossip, and career ladder climbing, A banking consultant recently advised that establishing a solid operating culture starts at the very top of the organisation. He advised that, for banks, values need to be integrated with shared beliefs and a powerful business mission into an energising narrative that uniquely positions the bank for growth and profitability. The corollary for the NHS is a culture driven by patient safety not financial profitability (though increasingly many decisions about the NHS are being taken from a financial not clinical perspective.) If any organisational culture is managed incorrectly or (worse) left un-managed, it can become dysfunctional or toxic. In these situations the organisational culture of an organisation can become a liability, not an asset. It can even lead to the outright failure of that organisation.

“Speaking out safely” is a much less dramatic term than “whistleblowing“, but a whistleblower (whistle-blower or whistle blower)] is simply a person who exposes misconduct, alleged dishonest or illegal activity occurring in an organisation. The alleged misconduct may be classified in many ways; for example, a violation of a law, rule, regulation and/or a direct threat to public interest, such as fraud, health and safety violations, and corruption. Whistleblowers may make their allegations internally (for example, to other people within the accused organisation) or externally (to regulators, law enforcement agencies, to the media or to groups concerned with the issues). The term whistle-blower itself comes from the whistle a referee uses to indicate an illegal or foul play. Most whistleblowers are internal whistleblowers, who report misconduct on a fellow employee or superior within their organisation.

There is no doubt that whistleblowers have suffered in the past, and continue to do so, and that’s why the proof of the Berwick pudding is in the eating. The treatment of Dr. David Drew [@NHSWhistleblowr], a respected paediatrician with an unblemished 37-year career in the NHS, who was sacked in December 2010 for “gross misconduct and insubordination”, is shocking. Dr. Drew is a practising Christian, though far from a fundamentalist: indeed, he describes himself as “a Christian with questions” who has “coexisted peacefully with colleagues of all faiths and none for many years”. He told a tribunal that, when he was a senior paediatric consultant at Walsall Manor Hospital, he had emailed a well-known prayer by St. Ignatius Loyola, “To Give and Not to Count the Cost”, as an incentive to his staff. Later, when ordered to “refrain from using religious references in his professional communications, verbal or written”, Dr Drew asked the trust to provide examples of when such behaviour had been problematic: the only solid thing it came up with, he said, was the prayer. Dr. Drew has described the culture of the health service as one of “fear and oppression” that is “driven by the top”.

Gary Walker [@modernleader] has also spoken out against his horrific situation. Lawyers representing the United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust, where he used to be chief executive, had written to him threatening that if he went ahead with the interview, he would be in breach of a compromise agreement and that he might be forced to repay the settlement he had received as well as the Trust’s legal costs. The former head of an NHS trust last week also described the culture of the health service as one of “fear and oppression” that is “driven by the top”. Mr. Walker had been sacked the previous year on grounds of gross professional misconduct, the reason given that he swore in meetings. However, Gary Walker alleges that the reason behind his departure was far more complex – that because he made the decision to ignore government targets for non-emergency operations as there were more urgent cases to attend to, he was cornered into resigning from his post.

Patient safety should be the ever-present concern of every person working working under the NHS’ name. Berwick emphasised that the quality of patient care should come before all other considerations in the leadership and conduct of the NHS, and patient safety is the keystone dimension of quality. Berwick further argued that the most important single change in the NHS in response to this report would be for it to become, more than ever before, a system devoted to continual learning and improvement of patient care, top to bottom and end to end. Collaborative learning through safety and quality improvement networks can be extremely effective and should be encouraged across the NHS. Critical to understanding this approach is that the most effective networks tend to be those which are owned by their members, who determine priorities for their own learning. However, back to reality. According to Roger Kline, one quarter of the staff in the largest employer in Europe report that they were bullied at some point in the previous 12 months. The rate of reported bullying has doubled in just four years. This summer, the British Medical Association annual conference heard how a proper system of regulation needed to be introduced for managers so they could be held to account.

In Summer 2009, psychologists at the Occupational Psychology Centre (OPC) at the Open University undertook a safety culture review of 30 PCTs. Each PCT was questioned about how their NHS trust measured up against nine key building blocks that make up a safe culture. One of those safety culture building blocks was being a learning organisation. The OPC specialise in safety with particular emphasis within the healthcare and transportation sector. Their work has shown that safety critical organisations that embrace and work at being a learning organisation are more likely to have a strong safety culture. A NHS organisation that has a learning culture learns from its mistakes. It has a problem solving approach to safety issues, is responsive to change and adapts to change effectively overtime improving its systems, processes and procedures. It is argued that a learning organisation promotes and lives out a ‘just’ culture. Many frontline clinical staff will readily report the real sense of ‘firefighting’ which they have in any acute shift in the emergency room, and this will be the case even in the most well resourced departments in England. However, it is felt that employees must feel safe to raise safety issues in an open manner including those issues that they are personally responsible for. Their raised issues are then acted upon. This chimes very well with the ‘Nursing Times Speak Out Safely Campaign’.Some of the employees in organisations which have worked with the OPC inform the OPC hat they have a “blame culture” in their organisation. As a result they are reluctant or even worse are afraid to raise safety issues. This can be further toxic to any NHS entity in terms of its safety culture and safety performance. If these safety issues are not dealt with then they can be precursors to more serious safety critical safety incidents and accidents. One often hears of NHS staff saying that, ‘It was an accident waiting to happen. We have raised the issue before but no-one listens’.

Constructive steps can be taken against toxic cultures though.The first step is to identify the major problems by gathering information, This is easier said than done, as perpetuators of toxic environments are less than forthcoming with feedback. This makes it very difficult for managers to discover the root causes of problems and also to deliver solutions to improve the workplace, yet an anonymous employee survey can go a long way to uncovering what people really think about the workplace. However, it’s also really important for the leadership team to identify an ideal culture and values for their business, so that they can use that shared vision as their compass to guide them towards a more positive culture. Asking the question “What does an ideal day look like?” and getting very specific about capturing that ideal culture will be really useful to the leadership team in the coming months (and years) as the organisation begins to change its direction.Once an understanding of the major issues has been formulated, the HR team can develop the action plan. Ultimately, guiding an organisation through cultural change is a long-term strategy, and it takes a “do what it takes” mentality from all stakeholders to really turn a corner. If HR communicates the strategy positively, honestly and continuously many of the team will jump on board very enthusiastically.

According to the Nursing Times, speaking after the publication of Prof. Don Berwick report into NHS patient safety, Ms. Cumming, the Chief Nursing Officer, said it was important trusts had the appropriate staffing level on their wards but called on staff to raise concerns where it was not.She said staffing would be monitored by the Care Quality Commissions new chief hospital inspector Sir Mike Richards. As previously reported by Nursing Times, staffing levels will not be used routinely to trigger inspections but CQC inspectors will check them during visits.She further highlighted the importance of the Speak Out Safely campaign, which is calling for nurses to be able to raise legitimate concerns without fear of reprisal or blame. So, bit-by-bit the pieces of jigsaw are falling into place. There is no doubt that the ‘Public Interest Disclosure Act’ has been a damp squib in terms of protecting whistleblowers’ interests. Likewise, it appears the NHS has gone “power mad” in getting out the cheque books to pay for compromise and confidentiality agreements, rather than listening to the views of the stakeholders.

But the silence of lambs is perhaps coming to an end at last. By this I mean, the lambs are not going to quit bleating. Quite the reverse. Instead, “the quiet man is here to stay, and he’s turning up the volume”, as someone quite famous used to say… Many would, further, add this does just not apply to the whistleblowers and staff who have been ‘silenced'; but the views of some patients have been massively ignored too. And on top of that a complaints system which doesn’t seem to work, and an overly complex regulatory system which appears to be struggling. A briefest look at all the NHS reconfiguration consultations with Trust special administrators might confirm problems with the ‘patient engagement’ process, but hopefully the NHS will move ‘excelsior’ before the law intervenes.

Is the answer to abject failure of medical regulation yet more regulation?

There are parallels with the discussion of whether the financial sector was too lightly regulated in the events in the global financial crash. This also happened under Labour’s watch. And Labour got a fair bit of blame for that, despite the Conservatives appearer to wish the regulation in that sector to be even “lighter”. Despite uncertainties about the number of people who actually died at Mid Staffs, for statistical reasons, there is a consensus there are clear examples of care which fell below the standard of the duty-of-care. Such breach caused damage, within an accept time period of remoteness, causing different forms of damage. The problem in this chain of the tort of regulation is that there appears to have been little in the way of damages. It is clear that the regulatory bodies have found it difficult to process their cases in a timely fashion in such a way that even some members of the medical profession and the public have found distressing and unproductive. The medical regulators are, however, fiercely concerned about their reputation, which is why any rumour that you have beeen involved in a cover up, ahead of patient safety, is potentially deadly.

There is a mild sense of panic amongst government ranks, with the introduction of a ‘Chief Inspector of Hospitals’, conducting OFSTED type assessments, and a “legal duty of candour”. It is proposed that this new legal duty might apply to institutions rather than individuals, unless Don Berwick, currently running for Governor of Massachussetts, has any better ideas in the interim. Here is the first problem; the GMC and other clinical councils take a punitive retributive approach (if not restorative), rather than rehabilitative, and Sir Robert Francis QC has emphasised that this is a wider culture malaise where it is difficult to find ‘scapegoats’. Organisations such as Cure however point to the fact that nobody appears to have taken responsibility, and are reported to have a shortlist of people who they’d like to see be in the firing line over Mid Staffs. The GMC is not in the business of blaming organisations, only individuals. In fact, its code (GMC’s “Duty of a Doctor”) is set up so that Doctors can report other Doctors to the GMC, and even report Managers to the GMC.

There is a possibility that NHS managers are not even aware of the professional code of the Doctors who comprise a key part of the workforce, but paragraph 56 of the GMC’s “Duties of a Doctor” is pivotal in demanding Doctors see their patients on the basis of clinical need. This is this clause which provides the tension with the A&E “four hour wait target”, but it is perhaps rather too late for medics to flex their professional muscles over this years after its introduction.

56. You must give priority to patients on the basis of their clinical need if these decisions are within your power. If inadequate resources, policies or systems prevent you from doing this, and patient safety, dignity or comfort may be seriously compromised, you must follow the guidance in paragraph 25b.

Paragraph 25b provides the trigger where Doctors have a duty in their Code to let their NHS manager know:

25. You must take prompt action if you think that patient safety, dignity or comfort is or may be seriously compromised. (b) If patients are at risk because of inadequate premises, equipment*or other resources, policies or systems, you should put the matter right if that is possible. You must raise your concern in line with our guidance11 and your workplace policy. You should also make a record of the steps you have taken.

And indeed following the legal trail, according to the CPS, a person holding “public office” can have committed the offence of “misconduct in a public office” if he or she does not act on such concerns, according to current guidance:

Misconduct in public office is an offence at common law triable only on indictment. It carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. It is an offence confined to those who are public office holders and is committed when the office holder acts (or fails to act) in a way that constitutes a breach of the duties of that office. The Court of Appeal has made it clear that the offence should be strictly confined. It can raise complex and sometimes sensitive issues. Prosecutors should therefore consider seeking the advice of the Principal Legal Advisor to resolve any uncertainty as to whether it would be appropriate to bring a prosecution for such an offence.

(current CPS guidance)

It is a legal point whether a NHS CEO meets the definition of a person holding “public office”. However, few will see little point in a Doctor, however Junior or Consultant, reporting a hospital manager to the GMC for lack of resources. The GMC indeed have a confidential helpline where Doctors can voice concerns about patient safety, even other colleagues, but this itself is fraught with practical considerations, such as when data are disclosed beyond confidentiality and consent, or a duty for the GMC not to encourage an avalanche of vexatious and time-consuming complaints either.

Indeed, the whole whistleblower affair has blown up because whistleblowers feel they have to make a disclosure for the purpose of patient safety in an unsupporting environment, often directly to the media, because nobody listens to them at best, or they get subject to detrimental behaviour (humiliation or bullying, for example) at worst. Clinical staff will not wish to get involved in lengthy GMC investigations about their hospital, and it would be interesting to see how many the actual number which have resulting in any form of sanction actually is. This is even amidst the backdrop that more than half of nurses believe their NHS ward or unit is dangerously understaffed, according to a recent survey, reported in February 2013. The Nursing Times conducted an online poll of nearly 600 of its readers on issues such as staffing, patient safety and NHS culture. Three-quarters had witnessed what they considered “poor” care over the past 12 months, the survey found. Understaffing in clinical wards has been identified as a cause of nurses working at a pace beyond what they are comfortable with, and the subsequent effects on patient safety are succinctly explained by Jenni Middleton (@NursingTimesEd) and colleagues in their video for the “Nursing Times Speak Out Safely” campaign.

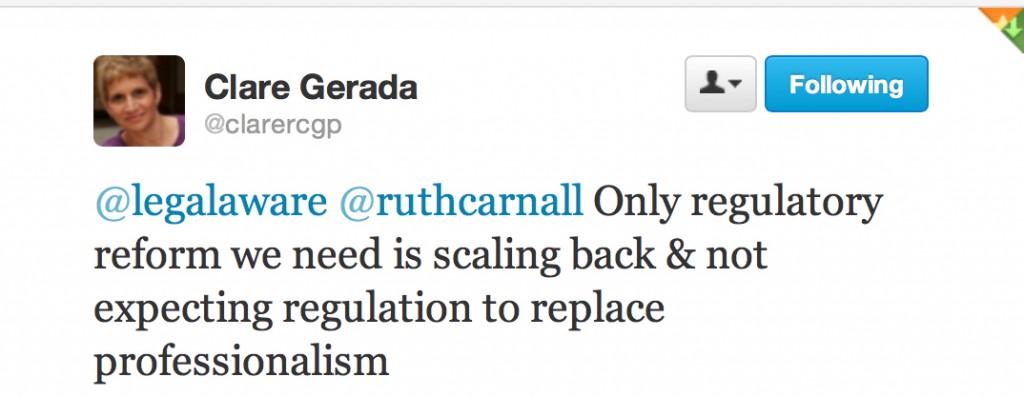

In the same way, the cure for recession may not be more spending (this is a moot point), the answer to a failure of medical regulation may not be yet further regulation. The temptation is to add an extra layer of regulation, such as an OFHOSP body which goes round investigating hospitals, but we have already introduced a ‘Chief Inspector of Hospitals’. At worst, further regulation encourages a culture of intimidation and secrecy, and Prof Clare Gerada clearly does not believe the NHS being caught up in yet further regulation is practicable or advisable:

And yet most would agree, following Mid Staffs and the revelations over CQC at the weekend that ‘doing nothing is NOT an option’ (while conceding that a “moral panic” response cannot be appropriate either.) The fundamental problem is that this policy gives all the impression of being designed in response to a crisis, how acute medics work in ‘firefighting’. Likening patient safety to the economy, it might be more fruitful to focus attentions to the other end of the system. This is the patient safety equivalent of turning attention from redistributive (or even punitive) taxation to predistribution measures such as the living wage. Some advocates call for a greater emphasis on compassion, and reducing the number of admissions seen in the Medical Admissions Unit or A&E, but in a sense we are coming full-circle again in the underlying argument of an under-resourced ward being an unsafe one. Transplant on this a political mantra that the main parties have had divergent views about whether NHS spending is adequate now or has been adequate before, in apparent contradiction to the nearly £3bn savings which were not ploughed back into patient care. or the £2bn suddenly found for the complex implementation of the Health and Social Care Act (2012). The existing regulatory mechanism for complaints to be made about under-resourcing affecting patient safety is there, but the intensity of the incentive for professionals using this mechanism appears to be low. Professionals will argue that they have a professional duty to maintain patient safety regardless of yet further regulation, but professionals have reported the mission creep of deprofessionalism in the NHS for some time now. Here, the medical professions have a mechanism of holding the NHS to account, and, if adverse reports were investigated quickly and acted upon, it is possible that NHS CEOs are not overly rewarded for failure. But if this mechanism is considered unfeasible, along with a “new improved” performance management system incentivising somehow ‘whistleblowing’, it’s back to the drawing board yet again.