Home » Posts tagged 'Simon Stevens'

Tag Archives: Simon Stevens

This is not scaremongering or conspiracy. Personal health budgets do promote privatisation.

The question is not whether personal health budgets will promote privatisation. The more interesting question is how they will do so.

I have been concerned that anyone who legitimately raises concerns about the current direction of travel from the main political parties has been dismissed as a ‘quack’. The scope for conspiracy theories hypothesising is of course enormous, but any CEO trying to formulate strategy will wish to think a few steps ahead.

“Personal health budgets” (PHBs) are normally sold under the truncheon of “look at how it’s worked for X’, and of course single case anecdotes of where they have worked for people are good to hear.

I would be the first to accept David Cameron’s approach, that it is not where you have come from it’s where you’re going to. But I cannot accept this in this scenario.

I do not wish to play the man not the ball here. But to ignore his career experiences would be daft, given that his CV would have contributed to get him his job as CEO of NHS England in the first place.

From 1988 to 1997 Stevens worked as healthcare manager in UK and internationally.

In 1997 he was appointed Policy Adviser to two Secretaries of State for Health (Frank Dobson and Alan Milburn) and from 2001-4 was health policy adviser to Tony Blair. He was closely associated with the development of the NHS Plan 2000.

From 2004-6 he was President of UnitedHealth Europe and moved on to be Chief Executive Officer of UnitedHealthcare Medicare & Retirement and then President, Global Health and UnitedHealth Group Executive Vice President of UnitedHealth Group.

He is more than aware of how the private insurance system works.

Let’s get this straight – it is simply untrue that PHBs are ‘great for mental health‘. Take for example a young lady poorly medicated for bipolar affective disorder, really at risk of making impulsive choices. She goes on a spending spree, thus blowing at one go her PHB.

Or take a 52 yr old man with behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia with normal memory. He is also prone to risk taking behaviour as part of his condition. He goes on a spending spree too, thus blowing his budget.

So we can all play the anecdote game.

Clinical Commissioning Groups do not have any requirement to be populated by clinicians, though ideally this would help. They are responsible for working out how to spend NHS money amassed legitimately from the taxpayer. Therefore the NHS is not strictly speaking free, although a founding value has thus far that it is free at the point of need.

They are also interested in the demographics of their population – how ‘risky’ subgroups might contribute in generating a hefty bill for the local population. That’s why there are gizmos such as the ‘dementia prevalence calculator’, for example. To that end, clinical commissioning groups in allocating resources according to risk function exactly like insurance entities. They just happen to be in the state.

The ‘money following the patient’ strap line hasn’t come from nowhere. It would be perfectly feasible for you with your allocated budget to transfer it to a private insurance entity without any obstacles. This is one of the main concerns of ‘competitive markets’.

The idea that PHBs might be best for people with long term conditions not best for people who are fit and healthy is setting up the NHS for a fall, though. Lord Norman Warner talked this week of how he would like the NHS to be serving people to ‘live well’.

But if people with long term conditions are ‘looked after’ in the early stages of the policy, and people who’ve had good experiences can encourage other people to adopt them, and if ‘brokers’ who have something to gain financially from the introduction of this policy can get their message across, they might endorse this plan.

The plan though is dangerous for them as they’re the ones who are left voluntarily in the State’s system, leaving politicians with the right mood music for healthy living people to leave the system, and to seek private insurance. That is the real danger of the way the system is going.

None of the above is far fetched. None of it is inaccurate. It is simply a statement of fact.

Sir David Nicholson has often remarked that private insurance markets would not work for certain complex conditions such as dementia, where it might be possible to ascertain with a high degree of certainty an individual’s risk of developing some family forms of the condition.

And you can see where this is heading can’t you? Certain people with dementia with strong risk factors for dementia genetically will be obliged to disclose this information to private insurers, here or abroad, and face astronomic premiums (sic) as insurance companies will not want to take on the risk.

And not all old people ‘cost’ the NHS – it is the last few months of life which are really expensive for any healthcare system.

Nicholson is right.

Andy Burnham MP, as Shadow Secretary of State for Health, must have as his primary interest, whatever the inglorious past of some policy decisions of Labour, the concerns of the voters.

They have said clearly on numerous occasions that they do not wish for ‘privatisation through the back door’, whatever one’s views on the private v State debate.

If voters do not want privatisation through the back door, the UK Labour Party should be very wary of going further with this policy. An unintended consequence is that, conspiracy or not, this policy might ultimately be setting up the NHS to fail. And it might be a perfectly intended consequence for some.

Innovations in dementia can be driven from the NHS too

It’s not as if the NHS has never thought about innovation.

In 2011, it published a report called “Innovation: health and wealth“.

The barriers to innovation are well known. The report indeed provides a good synthesis of some of the more common barriers.

Simon Stevens, as NHS England’s new CEO, in identifying private healthcare firms as key players is bound to have produced fireworks.

Simon Stevens has highlighted “the innovation value of new providers” in the provision of health services. He said failure to appreciate that value was one of a number of issues the NHS collectively had got wrong.

This to me is a reasonable point, even if articulated somewhat aggressively.

For every good innovative idea, there are thousands of turkeys. For this, you need to take creative risks in a healthy innovative culture.

The NHS really has problems with talking risks particularly in light of the intense ‘zero fault’ memes sent out by Jeremy Hunt, the current Secretary of State for Health.

Also there’s another elephant in the room.

Many junior medics get through medical school without any training in any form of business management, let alone innovation management.

Innovation management is a rewarding field which I studied for my MBA.

It’s not simply doing ‘more for less’ as popularly espoused by self-appointed ‘entrepreneurs’ and ‘innovators’.

Therefore, measuring any beneficial outcomes in the NHS, and rewarding them is intrinsically difficult. For this, the NHS needs to be seen to rewarding and training properly its innovators.

Addressing an audience of 300 health professionals in Newcastle, Stevens said he was “struck by the misplaced consensus that seems to exist within the health service on various issues”.

There is also, though, a powerful consensus amongst some that the NHS “can’t do “innovation.

Drawing on his decade of experience in global healthcare working for the US company UnitedHealth, Stevens said: “Things that are assumed to be inevitable care delivery constraints here often turn out not to be in other countries.”

I don’t particularly know what Stevens’ motives are.

It could be that the present government wishes to promote social enterprises and mutuals, through longer-term investor tools such as social impact funds, so that multinational corporations can go into strategic alliances with social enterprises to compete with the NHS for contracts.

This might be consistent with “the critical role of the third sector, and the innovation value of new providers”.

Certainly, the private sector does an important rôle to play in innovations in dementia, such as assistive technologies and ambient-assisted living.

But the idea of outsourcing innovation to the private sector is one for me which lacks imagination, but will transfer resources from the NHS to multinational corporations and social enterprises.

I actually do not have an ideological objection to this, though many will do.

But I do find sad that Stevens has given a speech which acts as a powerful market signal to his intentions. It’s almost as if Stevens in one foul swoop has intimated that the NHS is incapable of “doing” innovation, and – even more dangerously – has ignored the progress which had been made.

Simon Stevens. Is it not where you’ve come from, but where you’re going to?

The new NHS England Chief Executive is Simon Stevens.

Hailed as a ‘great reformer’, the first accusation for Simon Stevens is that he has been parachuted in to change the culture of the NHS. For all the recognition of patient leaders and home-grown leaders in the NHS Leadership Academy, it is striking that NHS England has made an appointment not only from outside the NHS but also from a huge US corporate. Indeed, Christina McAnea, head of health at the union Unison, told the Today programme on BBC Radio 4: “I am surprised that they haven’t been able to find someone within the NHS.”

A person like Stevens is likely to bring a breadth of managerial experiences, although he has never done a hospital job. He is no expert in land economy either. Despite the drama, the transition of the NHS to a neoliberal one has been on a fairly consistent course, as I explained previously in a now quite famous blogpost. I have also discussed how competition was introduced as a major plank in the Health and Social Care Act (2012) despite the overwhelming evidence against its implementation, known at the time; and how the section 75 and associated regulations would be the mechanism to achieve the ‘final blow’ for liberalising the NHS market. Where possibly English health policy experts have failed, perhaps, in their overestimation of the predeterminism that has taken place in England’s health policy since 1997. Changes of government have brought with it various changes in emphasis, such as the Blairite need to ‘reform public services’, possibly away from a socialist centre of gravity. The changing health policy has also had to take on board changes in politics, economics and legal considerations in the last few decades.

The suggestion that NHS England could have chosen ‘a more socialist CEO’ in itself is fraught with criticisms. Can you ‘a bit’ socialist or ‘half socialist’? Indeed, can you implement a ‘socialist NHS’ without implemented a sharing of resources across various sectors, including education or housing? People who don’t wish to engage with such arguments often end up with extremist Aunt Sally arguments referring to socialism as a state like pregnancy or like a religion, but the ideological question still remains can you have state provision of the NHS on a sliding scale from 0-99% private provision? With the current debate about whether Labour would renationalise the railways, in light of the fact that monies are potentially found out of nowhere for foreign military strikes at the drop of a hat, this discussion has never been more relevant potentially. One of David Cameron’s famous phrases, somewhat ironic given his background at Eton and Oxford, is, apparently: “It’s not where you’ve come from – it’s where you’re going to.” This may apply to not only Stevens but the whole of NHS England, especially if you hold the alternative viewpoint that the NHS could and/or should jettison its ‘founding principles’.

It is all very easy to play the ‘man’ not the ‘ball’, and certainly NHS England already has its strategic goals. Nonetheless, it is critically important for any organisation, particularly the NHS, to think about how much of its strategic aims have to be driven from the very top. Attention has turned to the US company he has spent the last decade with as a senior executive: United HealthCare. There is no point, however, being necessarily alarmist. Pro-NHS campaigners will be mindful of this now largely discredited campaign. Resorting to such emotive messaging may distort the genuine discussion which needs to be had about the future of the NHS in England.

Mr Stevens, 47, was Tony Blair’s health advisor between 2001 and 2004, and before that advisor to then-health secretary Alan Milburn. Simon Stevens’ CV reveals that he was a Trustee from The Kings Fund, London (a health charity) between 2007 – 2011 after being a Councillor for Brixton, south London London Borough of Lambeth 1998 – 2002 (4 years). It has even been alleged that Stevens has been a member of the Socialist Health Association. The NHS budget has been notionally protected – it is rising 0.1% each year at the moment – the settlement still represents the biggest squeeze on its funding in its history. Labour has criticised previously how the Coalition has misrepresented the current state of NHS spending. The currently chief executive of the English NHS, David Nicholson, recently called for politicians to be “completely transparent about the consequences of the financial settlements” for the NHS. Nicholson’s point perhaps was that, although politicians say the NHS has been protected financially, this was only relative to real cuts in other areas of government and, crucially, not in terms of the demands on healthcare.

A clue as to how Mr Stevens will run the NHS could be seen earlier this year when he co-authored a report for UHC arguing that the Obama administration could save $500bn in Medicare and Medicaid funding over the next 10 years by more aggressively coordinating medical care for pensioners and the poor. This pitch will have been very attractive to Sir Malcolm Grant. Mr Stevens said instead of concentrating on either cutting benefits or cuts to doctors and hospitals, the US healthcare debate should focus on a “third way”: cutting costs while improving care. A similar challenge awaits him at the NHS. However, the Keogh mortality report identified that safe staffing was a pivotal reason why NHS Trusts had failed un basic patient safety. Stevens is definitely unlikely to find a “third way” between balancing budgets to provide unsafe clinical staffing levels and adequate patient safety.

Some ministers have repeatedly praised Blair’s attempts to reform services, in the earlier period of their administration. In a speech to the Tory party conference earlier this month, Jeremy Hunt highlighted the efforts of Mr Blair and Mr Milburn to increase the use of the independent sector to reduce waiting times. However, Mr Stevens is also associated with the introduction of NHS targets, and helped create the key plan which brought them in. This NHS “target culture” which have been repeatedly attacked by the Coalition as playing a part in scandals such as that at Mid-Staffordshire, as a root cause of the ‘bully boy’ tactics (allegedly) by some NHS CEOs to achieve Foundation Trust and receive personal bonuses. Particularly important then for Labour is not where it has come from but where it is going to.

Andy Burnham MP, Shadow Secretary of State for Health, has repeatedly stated that a Labour Government will repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2012) in its first Queen’s Speech in 2015. It has also been made clear that Labour will do this, even if Burnham is recruited laterally to a different job. For any corporate strategy, a number of drivers will be essential to remember: for example environment, socio-cultural, technological, legal and economics. With the appointment of Stevens “just in time” for the privateers – quite possibly, it is still remarkable that working out the legal niceties of working out ‘mission creep’ in the special administrator powers of NHS configurations is ‘work in progress’. Only this week, it was reported that the Royal Colleges of Physicians have genuine concerns about whether other amendments to the Care Bill are in the patients’ interest, pursuant to the current high-profile mess in Lewisham. Both Stevens and Grant are fully aware that they will have to deal with the political landscape, whatever that is, on May 8th 2015 and afterwards.

Strategic demands of the NHS

Currently NHS England has a number of powerful strategic demands, which could even appear at first blush inherently contradictory. For example, a purpose of patient safety management will be to minimise risk of harm to patients, whereas successful promotion of innovation can be achieved through encouraging risk taking in idea creation. Whatever Stevens’ ultimate vision – and this is why the implementation of Health and Social Care Act (2012) has been so cack-handed – it is essential that industry-acknowledged frameworks for change management are considered at the least. For example, in Kotler’s model of change management, the leader (Stevens) will not only have to ‘create a powerful vision’ but ‘communicate the vision well’.

Patient safety

There is no doubt that the Mid Staffs scandal was a very low point in the NHS. But there’s nothing like a good scandal for focusing the mind? In a general article in June 2009 by James O’Toole and Warren Bennis in the Harvard Business Review (“HBR”), the authors that no organisation could be honest with the public if it’s not honest with itself. This simple principle has been slow to come into the English law, though it has been introduced as an amendment in the Care Bill (2013). A notion has arisen that members of senior management turn a blind eye to failings deliberately (“wilful blindness“), but interestingly the authors draw on the work on Malcolm Gladwell. In his recent book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell had reviewed data from numerous airline accidents. Gladwell remarks, “The kinds of errors that cause plane crashes are invariably errors of teamwork and communication. One pilot knows something important and somehow doesn’t tell the other pilot.” The question is, necessarily, what a CEO can do about it. The authors propose two solutions inter alia. One is to “reward contrarians”, arguing that an organisation won’t innovate successfully if assumptions aren’t challenged. The authors advise organisations, to promote a ‘duty of candour’, to find colleagues who can help, who can be promoted, and who can be publicly thanked. The authors also advise finding some protection for whistleblowers: this might even include people because they created a culture of candour elsewhere. Initiatives such as the Nursing Times ‘Speak Out Safely’ are likely to be highly influential in catalysing a change, but a lot depends on the legal protection for whistleblowers given the current perceived inadequacies of the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998.

There is a growing realisation of implementation of patient initiatives has to be ‘top down’ as well as ‘bottom up’. For example, for Diane Cecchettini, president and CEO of MultiCare Health System, Tacoma, Washington, the key to patient safety has been achieved through leader engagement. She has developed an over-arching strategic framework for quality and safety that has served as the catalyst for the development of multi-year strategic quality and safety improvement plans throughout the MultiCare Health organisation.

Innovation

Innovation is another thorny subject. Innovation (and integration) is always going to be on a dangerous path if primarily introduced as an essential ‘cost cutting measure’, rather than bringing genuine value to the healthcare pathways. Nonetheless, the issue of financial sustainability of NHS England is a necessary consideration, even if the term ‘sustainability’ is open to abuse as I argued previously.

Innovation means different things to different people. As there is no single authoritative definition for innovation and its underlying concepts, including the management of innovation, any discussion on the topic becomes difficult and even meaningless unless the parties to the discussion agree on some common terminology. Innovation requires breaking away from old habits, developing new approaches, and implementing them successfully. It is an ongoing, collaborative process that needs considerable teamwork and skilled leadership. CEOs’ ability to lead their top management team successfully may provide the guidance and inspiration needed to support others to overcome obstacles and innovate. CEOs must provide effective leadership for top management teams to help organizations innovate.

It has been argued that, “There is no innovation without a supportive organisation”. Reviewed in the “International Journal of Organizational Innovation” by de Waal, Maritz, and Shieh (2010), innovation scholars have proposed numerous factors that, to a greater or lesser degree, have the potential to make organisations more conducive to innovation:

- A culture that encourages creative thinking, innovation, and risk-taking

- A culture that supports and guides intrapreneurial liberty and growing a supportive and interconnected innovation community

- Cross-functional teams that foster close collaboration among engineering, marketing, manufacturing and supply-chain functions

- An organisation structure that breaks down barriers to innovation (flat structure, less bureaucracy, fast decision-making, etc.)

- Managers at all levels that support innovation

- A reward system that reinforces innovative and entrepreneurial behaviour

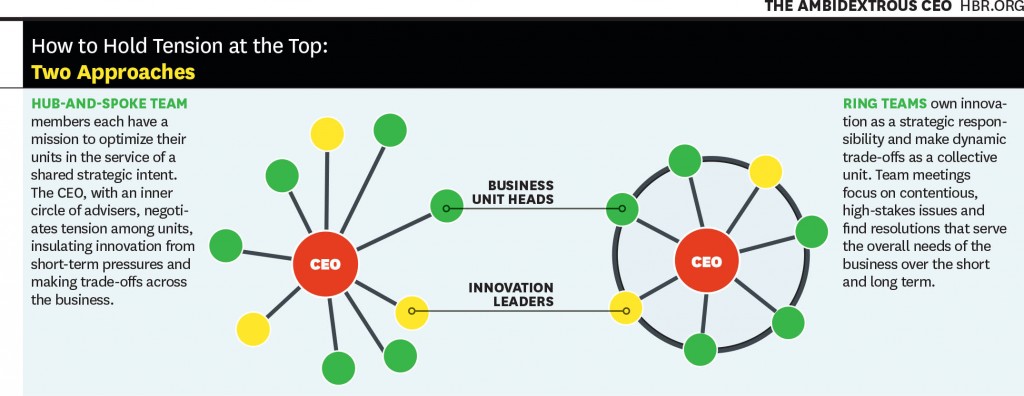

Communicating the vision, as described earlier, is also important for innovation management. This is a potential problem with KPMG’s Mark Britnell’s thesis of how raising the private income cap could promote innovation, as NHS and private wards nearly always co-exist in separate hospitals in ‘NHS Trusts’. It is argued in an interesting article in the Harvard Business Review (2011) entitled, “The ambidextrous CEO”, conflicts in innovation management are best resolved at the very top, and this could be filtered to the rest of the organisation through models such as “hub and spoke”.

It’s probably fair to say that a lot actually rests on the shoulders of CEOs in how innovative they wish their organisation to become. And certainly the ‘high-profile transfer of CEOs’, almost akin to the transfer of footballers, has attracted considerable recent interest, such as Burberry’s Angela Ahrendts joining Apple.

Thomas D. Kuczmarski in a rather sobering paper entitled, “What is innovation? The art of welcoming risk” identifies the CEO even as a potential ‘barrier-to-innovation’ (as far back as in 1996):

If you are like most CEOs, you are in a state of denial. Most CEOs express a fervent belief in new ideas and claim to be committed to innovation, but actions speak louder than words.

The truth is that most CEOs and senior managers are intimidated by innovation. Viewing it as a high-risk, high-cost endeavor, that promises uncertain returns, they are afraid to become advocates for innovation. However, because it clearly represents challenge and opportunity, most CEOs deny their reluctance to embrace innovation. They deny that their new product programs are underfunded or understaffed. They deny that they are closed to new ideas or ways of doing business. They deny that they fail to encourage or reward innovative thinking among their employees. Most of all, they deny that they have created within their organizations a fear of failure that stymies the urge to innovate.

All this denial is not good. It sends mixed messages throughout the organization and sets up the kind of second-guessing and playing politics that can undermine even the best developed business strategies. Unwilling to be measured by their failures, employees are reluctant to take risks that the successful development of new ideas demands and, as a result, even the desire to innovate diminishes.

Stevens (2010) himself has publicly expressed concerns on failure to innovate. For example, in the Harvard Business Review, he discussed how information on new clinical treatments spreads across the world quite fast, and how healthcare systems which fail to be flexible enough on picking up on this are likely to fail. Stevens’ example is striking:

However, the rate at which innovations are being translated into actual improvements is agonizingly slow — a frustrating problem that dates back to the world’s first controlled clinical trial in 1754. It proved that lemons prevented sailors from getting scurvy, but it then took another 41 years for a navy to act on the results. Wind the clock forward to today, and 15 years or so after e-mail became common, it turns out that most patients still can’t communicate with their doctors that way.

Deutsch (1973, 1980) proposed that how individuals consider their goals are related, very much affects their dynamics and outcomes. The basic premise of the theory is that the way goals are structured affects how people interact and the interaction pattern affects outcomes. Goals may be structured so that people promote the success of others, obstruct the success of others, or pursue their interest without regard for the success or failure of others. Deutsch identified these alternatives as cooperation, competition, and independence. In cooperation, people believe that as one person moves toward goal attainment, others move toward reaching their goals. They understand that others’ goal attainment helps them; they can be successful together. In competition, people, believing that one’s successful goal attainment makes others less likely to reach their goals, conclude that they are better off when others act ineffectively. When others are productive, they are less likely to succeed themselves. They pursue their interests at the expense of others. They want to ‘win’ and have the other ‘lose’. With independent goals, people believe that their effective actions have no impact on whether others succeed. Researchers have long debated whether cooperation or competition is more motivating and productive (Johnson, 2003). As regards the thrust of what happens in reality following 2015, therefore, the political landscape does very much happen. If Labour wish to promote collaboration perhaps through integration of health and social care, the entire nature of this dialogue will change. And the new CEO of NHS England will have a pivotal rôle in the organisational learning of the whole of NHS England.

Further implications for Labour in general policy

Some further issues are raised by Stevens (2010) short piece for the HBR. Labour has begun to ‘apologise’ for accelerating progress in the market of the NHS.

Introducing the ‘fair playing field’ of the market – another bogus concept which has gone badly wrong

The policy of ‘independent sector treatment centres’ under Labour has been much discussed elsewhere. PFI, although originally a policy which arose out of David Willett’s pamphlet for the Social Market Foundation (“The opportunities for private funding in the NHS“), and in the Major Conservative administration (see the work of Michael Queen), has seen various reformattings itself during successive Labour (Brown/Blair) and Conservative governments (Osborne/Cameron). The issue is that failing Trusts are not big to fail, unlike banks. Trusts ‘going bust’ are open to asset stripping from the private sector.

The opening up of the market is encapsulated in the document from Monitor, “A fair playing field for NHS patients”. Increasing the number of market providers not only potentially boosts ‘competition’ in the market, but also produces a supply of ‘predators’ in the terminology of Ed Miliband’s much maligned conference speech in Liverpool in 2011. This conference speech nevertheless successfully signposted with hindsight the highly celebrated political notion of ‘responsible capitalism‘. Many on the left now view the concept of ‘a fair playing field’ as being entirely bogus with the onset of decisions being made in the NHS on the basis of competition law not clinical priorities.

To what extent Burnham will wish to make a break from the past is the crux of the issue. Having signalled that he wishes to repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2012) is the beginning of a long journey. At some stage, there will be a debate again about how much of the NHS is actually funded out of taxation, or whether, as anti-privatisation campaigners fear, whether we need to re-consider the explosive issue of co-payments or subsidiary payments. Burnham has signalled that he wishes to implement a NHS ‘preferred provider’ policy, in trying to capture lost ground on the increase in private provision in the NHS. But even here he may run into difficulty if legally the US-EU Free Trade Treaty, with discussions currently underway, make it impossible for him to implement such a policy.

But as it is, injecting ‘competition’ into the system could be in fact be the sort of competition which has dramatically failed in the energy sector. It is noteworthy that Ed Miliband has decided to whip himself up into a frenzy publicly about this in parliament, as part of the #costoflivingcrisis, rather than adopting the technocratic bureaucratic approach of waiting for the Competition Commission to investigate this particular market. It is well known that encouraging new entrants to the healthcare markets, even in the third sector, is fraught with difficulties, with the market occupied by a few well-known private sector brands. Here, the scandal of what are high prices, unlike ‘energy’, may remain a hidden scandal, as the customer is not directly the patient: it is the clinical commissioning group.

What do CCGs actually do?

Andy Burnham, to emphasise that he is not going to embark on yet another costly disorganisation in 2015, has explained that he intends to make the existing structures ‘do different things’. However, there is currently a bit of muddle as to what CCGs actually do.

Stevens states that:

Consolidation among care providers and barriers to entry for new hospitals mean that health-care delivery mostly relies on incumbents doing a bit better, as opposed to step changes in productivity from new entrants. Yet in the rest of the economy, new entrants unleash perhaps 20% to 40% of overall productivity advances.

Of course, with Stevens having leaving the NHS after ‘Blair times’, United Health has been set to become one of the beneficiaries of the advancing liberalisation of the NHS market.

It is now becoming more recognised that CCGs are in fact state aggregators of risk, or state insurance schemes. I had the opportunity recently of asking Sir Malcolm Grant in an exhibition at Olympia whether he had any disappointment that clinicians were not leading in CCGs as much as they could be, and of course he said “yes”. But strictly speaking GPs do not ‘need to’ lead CCGs as they are insurance schemes. The notion of ‘GP-led commissioning’ is widely felt to be a pup which was usefully actioned by the media to sell the controversial recent NHS reforms to a suspicious public.

This may or may not be what Stevens feels, albeit Stevens was speaking from the position of senior management in an aggressive US corporate at the time:

Increasingly, health plans should look to become ‘care system animators’ and not merely risk aggregators and transactional processors. Using their population health data, their information on clinical performance, their technology platforms, and their ability to structure consumer and provider-facing incentives, health plans have enormous potential to help improve health and the quality, appropriateness and efficiency of care. At UnitedHealth Group, our new Diabetes Health Plan, new telemedicine program, new eSync technology, and work on new models of primary care are all examples of what this can mean in practice.

Conclusion

In a perverse way, Stevens has an opportunity now to make the NHS work using knowledge of what the private sector does best and worst, in the same way that he was able to take advantage of his NHS policy knowledge while working for United Health. To what extent he will be concerned about the shareholder dividend of private companies as the NHS buggers on regardless will be more than an academic interest. No doubt the media will follow Stevens’ share interests with meticulous scrutiny.

The extent to which, however, he as the CEO can mould the culture of the NHS is an interesting one, however. If he (and ministers) believe that that it is he who should be leading change, then his default pathway will be one of private sector organisational change, with focus on patient safety and innovation through leadership. He will, however, run into problems if the NHS becomes primarily stakeholder-led. In other words, if patient campaigners continue to advocate that “patients come first“, especially through successful campaigning on patient safety or patient-led commissioning, Stevens might find his task is much harder than being a CEO of an American corporate.

Simon Stevens may seem like a powerful man. But there could be a man who is even more powerful from May 8th 2015, who might have a final say on many areas of policy, ahead of Stevens and Grant.

And that man is @andyburnhammp.

References

Birk, S. (2009) Creating a culture of safety: why CEOs hold the key to improved outcomes. Healthcare Executive (Mar/Apr), pp. 14-22.

de Waal G. A, Maritz P.A, Shieh C.J.(2010) Managing Innovation: A typology of theories and practice-based implications for New Zealand firms, The International Journal of Organizational Innovation 01/2010; 3(2):35-57.

Deutsch, M. (1973). The Resolution of Conflict. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Deutsch, M. (1980). ‘Fifty years of conflict’. In Festinger, L. (Ed.), Retrospections on Social Psychology. NewYork: Oxford University Press, 46–77.

Johnson, D. W. (2003). ‘Social interdependence: interrelationships among theory, research and

practice’. American Psychologist, 58, 934–45.

Kuczmarski, T.D. (1996) What is innovation? The art of welcoming risk, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 13(5), pp. 7-11.

Stevens, S. (2010) How Health Plans Can Accelerate Health Care Innovation, available at:

http://blogs.hbr.org/2010/05/how-health-plans-can-accelerate/

Toole, J.O., Bennis, W. (2009) What’s needed next: a culture of candor, Harvard Business Review, June edition, pp.54-61.

Tushman, M.L., Smith, W.K., Binns, A. (2011) The ambidextrous CEO, June, pp. 74-80.