Home » Posts tagged 'section 75 regulations'

Tag Archives: section 75 regulations

Cutting the NHS cake. Who benefits from NHS competitive tenders?

In game theory and economic theory, a “zero-sum game” is a mathematical representation of a situation in which a participant’s gain (or loss) of utility is exactly balanced by the losses (or gains) of the utility of the other participant(s). If the total gains of the participants are added up, and the total losses are subtracted, they will sum to zero. Consider cutting a cake, where taking a larger piece reduces the amount of cake available for others; it is a zero-sum game if all participants value each unit of cake equally. In contrast, non–zero sum describes a situation in which the interacting parties’ aggregate gains and losses are either less than or more than zero.

As I have consistently maintained with others, although the only reason I know about this at all is due to Dr Lucy Reynolds at the London School of Health and Tropical medicine, the purpose of section 75 Health and Social Care Act (2012) was to ensnare the NHS in a free market. This market would be run according to competition rules, governed by European rules regulating ‘economic activity’, and the big corporates Circle, Virgin and Serco, for example, would have massive competitive advantage through their supplier power, economies of scale, and known expertise in procurement across a number of sectors. The National Health Service, which does not have the resources or expertise in complex procurement yet, would be at disadvantage, and unable to compete effectively.

That the market was not ideal for ‘our National Health Service’, as Prof Sir Bruce Keogh, Medical Director of the NHS, affectionally calls it has been seen in a number of recent instances. One for example is the furore with the privatisation of ‘Plasma Resources UK‘, with concerns about asset-stripping type behaviour of private equity firms for future transactions. The NHS has also not be able to implement ‘patient choice’ in complex rules about mergers, seen entirely through the competition law prism. As such Tony Blair’s dictum that ‘it doesn’t matter who’s providing my services, as long as they’re of the highest quality and I’m not paying for them’ runs into four big problems professionally.

- Firstly, if you have a carousel of different providers in your care, this is a major barrier to continuity-of-care. Continuity-of-care helps for the reason that fewer mistakes are made by clinicians, and also saves on repeating transaction costs for doing the same thing, such as medical investigations, again-and-gain (with no change in results).

- Secondly, outsourced services obtained through price competitive tendering might cost less, but profit becomes more important than value in the return on investment in services run by the private sector on the NHS’ behalf (this is why the legal profession wisely decided to abandon competitive tendering on the basis of lowest price, because of the overwhelming criticism from senior lawyers of ‘a race to the bottom’).

- Thirdly, it is a deception to the public, who feel that their services are being run by the NHS, whereas they are in fact being run by a totally alien entity in NHS uniforms.

- Fourthly, it is not an innocuous ‘zero sum game’. For every gain in the private sector, there is a loss in the NHS both in morale, sustainable business plan and resources. This matters for the future of the NHS in its ability to run a comprehensive, universal service, but this will not matter if the Secretary of State absolves responsibility for running the NHS under law, and this aspiration gets deleted in time from the NHS constitution.

The NHS Support Federation have reported that commercial companies look set to gain £1.5 billion pounds worth of NHS funding from contracts issued within the last three months. This surge in commercial activity follows the government’s new competition rules (section 75 of the Health and Social Care Act (2012), which came into force in April.) Over a hundred opportunities have been advertised according to figures compiled by the NHS Support Federation. The latest contract notice is the biggest so far, to run community services in Cambridgeshire, and is worth £800 million over 5 years. The private sector is easily winning in this competitive market, since April 2013, a sample of clinical services contracts taken from official tenders websites found that only 2 had been awarded to the NHS with 16 going to the independent sector.

The data set used for this research was taken from two procurement websites where NHS competitive tenders notices are advertised in keeping with UK practice and contract law - TED OJEU and supply2health

- NHS clinical contract Notices Apr-Jun: (source: TED OJEU);

- NHS clinical contract Awards from April 2013 (source: TED OJEU);

- Contract Notices: Supply2Health from April 2013).

NHS competitive tenders have risen steeply. Contracts awarded since April 2013 show 16 to the private sector only 2 to the NHS. An estimated £1.5 million worth of contracts have emerged in the first 3 month since the competition regulations were passed by Parliament. Outsourcing is increasing fastest in diagnostics, mental health, domicillary care and pharmacy. The largest appeared on the TED website at the end of the sample period, a contract to provide a wide range of community health services in Cambridgeshire. It is worth £800m over five years. The contract trumps the value of similar arrangements that have been made with Serco and Virgincare to run services in Suffolk (130m) and Surrey (500m). There were around twice the number of NHS competitive tenders for clinical services compared with the same quarter last year advertised on the Official Journal to the European Union – TED. Their sample is made up of 106 clinical contracts, so not those involving the pure supply of goods. Pharmacy contracts are included as a service that involves providing medical advice, but the supply of medical equipment is not. Ambulance contracts listed include those for blue light and patient transport.

It was predicted that the section 75 regulations (that passed through Parliament in April) would result in a sharp increase in the use of NHS competitive tenders as method of purchasing. The government, helped primarily by Lord Clement-Jones and Baroness Williams in the House of Lords, consistently argued that the section 75 regulations would not give primacy to the mechanism of ‘price competitive tendering’. The business problems of price competitive tendering are certainly infamous in other sectors, and, as a result of this ideological drive, outsourcing through price competitive tendering is being thrust upon the NHS (and also resisted) by the judicial system. In the NHS, there has been an increase in tendering activity in the April-June period 2013 compared to the same period last year, where a search through TED archives showed that around half the number contracts for clinical services were advertised compared to 28 contract notices (worth £1,045,668,000) in the Apr-Jun quarter a year later. There were a further 57 notices published on the supply2health website, of which the majority were competitive tenders, although in some cases the purchasing method appears not to have been finalised. There is a wide range of opportunities to run services being advertised, from a £50m group of ambulance services in Exeter, including blue light, to an advert inviting competition to provide a package of care for a single patient in Corby. The range of services is also widening. As mentioned above last year the government asked PCTs to increase competition and patient choice by extending their use of AQP for commissioning. A list of thirty nine treatments and types of care was produced.

There is growing list of care types that are being commissioned through NHS competitive tenders. These contain some of the largest contracts and have attracted interest from large companies like Virgin and Serco. In Devon Virgin recently began a contract to run children’s health services after a legal challenge failed to prevent the contract going forward.Despite well publicised problems with outsourced contracts for GP out of hours in several areas involving Harmoni and Serco, five further contracts have been advertised in five new areas (East Midlands, Hackney, North East, Surrey and Sussex, Sutton). Our local City & Hackney doctors have worked for two years to put together a new not-for-profit social enterprise (City& Hackney Urgent Healthcare Social Enterprise – CHUHSE) , which involves City and Hackney doctors varying their contract in order to provide an Out of Hours service. In February 2013, a GP-led social enterprise in Hackney lost its bid to take responsibility for out-of-hours care from private provider Harmoni, when the company’s contract expires on March 31. The service to be run by GPs had been intended to be be non-profit – i.e. local doctors are prepared to give up their evenings and weekends to ensure local people get the quality and continuity of service they need. However, Harmoni did not perform well elsewhere. In May 2013, it was reported that Care Quality Commission inspectors have found private company Harmoni in offence of running the out-of-hours (OOH) GP service for Hackney with so few doctors they are potentially placing patient’s safety at risk. The Care Quality Commission (CQC) had previously been reviewing staffing levels at Harmoni North Central London.The company admitted there had been no doctors based at Homerton Hospital on the evening of Easter Sunday, despite being contracted to provide a service when GP practices are closed. The CQC report has been published and concluded “there were not enough qualified, skilled and experienced staff to meet people’s needs”.

The way in which Labour had opened up the service, and brought in the “Tony Blair Dictum” is well known. The problem now is that there is an active competitive market, where there is no overall direction. Clinical Commissioning Groups are not GP-led in the majority, but followers of English policy know they were never intended to be. They were simply intended as state insurance schemes in the seminal ‘The Health of the Nations’ from the Adam Smith Institute. Recently, the following observations were made on May 19 2013:

“As only 22% of CCGs have a GP as accountable officer, there are those who believe that CCGs are simply management run organisations supported by a few enthusiastic GPs – PCTs in all but name.

Many of those working in CCGs would refute the suggestion, pointing to the fact that they are a membership organisation, and that the GPs are not supporters but the real engine of the CCG.

According to Wikipedia, ‘CCGs are clinically led groups that include all the GPs in their geographical area. The aim of this is to give GPs and other clinicians the power to influence commissioning decisions for their patients’. But are CCGs really clinically led?

The number of management directors varies according to the size of the CCG. Most (over three quarters) have a manager as Accountable Officer, and all have a Chief Financial Officer. Larger CCGs may also have a management director for quality, for strategy or commissioning, even for contracting. Where there is a director there is generally a management team, and so the risk is that much of the organisation can start to operate outside of the GPs’ control.”

Therefore, there is a good arguable case that “cutting up the NHS cake”, as first introduced by Thatcher and Major through its locking-in of PFI deals aka marketisation approach, regretfully advanced by Labour through continuation of the PFI approach and an addition of ‘independent sector treatment centres’ for good measure, and the Coalition’s continuation through advancing outsourcing with a view to final privatisation, does not necessarily benefit the patient. To provide balance, Andy Burnham has promised to repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2013), drive the competition arrangements into “reverse gear” in Part 3, and to introduce the ‘NHS preferred provider’. The patient ultimately cannot be ethically called a ‘consumer’ as it is a rigged market, and half of the relevant information, at least, is not available. It is clearly not a ‘fair playing field’ as private healthcare providers are able to make profits for shareholders, do not contribute to the training of junior doctors or nurses in the NHS, are immune from judicial review, and are immune from freedom of information requests. “Cutting up the NHS cake” was an unnecessary shot in the foot in English health policy. But if it means that the result is that private providers ‘cherrypicks’ the most profitable services, leaving the NHS with the most expensive and clinically challenging cases, this could see the whole leg requiring amputation. Otherwise, the NHS will die of septic shock, through a toxic combination of the policies of the Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat Parties in the House of Commons and House of Lords over time.

As few as five votes could mean the controversial section 75 NHS instrument get passed by their Lordships

This is by no means a “done deal” by any stretch of the imagination.

I had a pleasant conversation with Suresh Chauhan just now. He has done the research below.

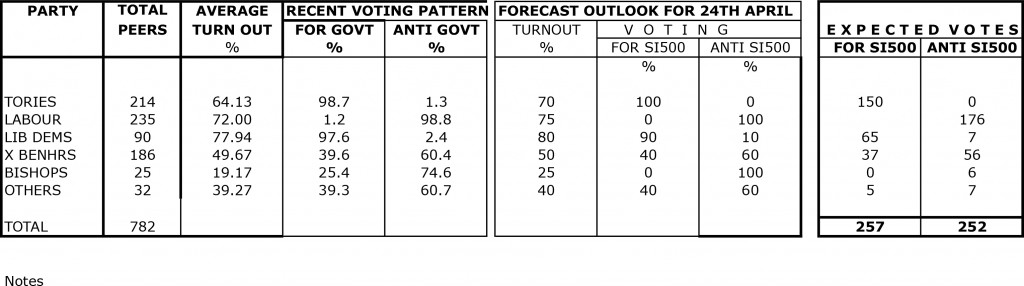

Suresh has tried to forecast the voting outcome on the Lords prayer/debate regarding SI500.

The figures are based on actual turnouts/voting patterns in this parliament.

His assumptions for the forecast are as follows:

- A large number of Conservative peers are alleged to have interests in private healthcare providers. It is noted that it is argued that they have not missed any opportunity to support the Conservative-led government’s NHS main legislation and statutory instruments.

- Many Liberal Democrat peers have been given false reassurances that the new statutory instrument goes no further than existing legislation. This is clearly not true, with the current Government having made the effort of putting onto the statute books such voluminous legislation for the purpose of maximising competitive tendering in the NHS. The Regulation 5 specifically establishes that there should be a competitive process unless for uncommon occasions, so it is utterly irrelevant how bids have been ‘sold’, in terms of ‘best value’, or ‘integrated care’. This is the direct effect of the proposed law, for which there are many reliable authorities who have produced authoritative commentaries, and it is hard to escape this jurisprudence. Furthermore, it is simply not the case that all disputes can be channeled through Monitor. All private providers will have the ability to pursue litigation in the High Court, and it is anticipated that with this legislation (and relative lack of experience and skills in procurement as well as financial resources) CCGs will be coerced into exercising caution. Fear of the bargaining power of suppliers clearly does not promote competition in the patients’ best interests necessarily, and it had been discussed in the parliamentary process that parliament would NOT force stakeholders into a competitive tendering process.

- Behaviour of Crossbenchers is difficult to predict.

- Turnout of Bishops has normally been described as ‘disappointing’.

The key conclusion from this research result is that the vote is likely to be extremely close in reality, and depends on a good turnout from the Labour Lordships.

It is therefore imperative that the Labour peers turn up for this particular vote. Lord Steve Bassam (@stevethequip) is Brighton’s cricketing labour chief whip in the Lords. Lord Bassam is Member of Shadow Cabinet, and very conspicuously an ardent Brighton fan.

I am reliably told that the Labour Lords are though doing their best for the key vote on Wednesday.

It’s going to be extremely challenging for the vote anti-the instrument to be higher than the vote for-the instrument, because of the whipped Liberal Democrat vote.