Home » Posts tagged 'Prof Alistair Burns'

Tag Archives: Prof Alistair Burns

Prof Alistair Burns, National Clinical Lead for Dementia, asks, “Do you have problems with your memory?”

It is widely anticipated that Scotland on Monday 3rd June 2013 will support England in calling for a ‘timely’ diagnosis for dementia, leading to an emphasis of person-centred care. The issue of how that diagnosis is made is therefore alive and well.

A G.P. is of course is incredibly busy. It is possibly the hardest job in medicine. In asking patients in a General Practice whether they are aware of memory problems, it’s like to looking for any horses once they have bolted. In terms of English policy, at least an attempt to find these bolted horses is presumably welcome, given that the general impression is that we are missing many horses bolting under our very eyes.

The question which Prof Burns proposes that Doctors in passing might ask is,

“Do you think you have any problems with your memory?”

For an overview of the complexity of the dementias, I can recommend the excellent chapter 24.2.2 by Prof John Hodges from the current Oxford Textbook of Medicine. You can see it chapter-24-4-21. I am grateful to Prof Hodges for including my paper in his chapter on a diagnosis of a common form of dementia.

G.P.s consistently have warned that they are terrified about their patients being “scared” to see their G.P., in case this question pops up ‘on the sly’ and the possibility of dementia is raised publicly in the “confidential” medical notes. In theory, any of the disease processes can affect any parts of the brain, affecting any number of the cognitive functions of the brain, behaviour and personality according to the precise distributed neuronal networks affected. This means that memory might not be the presenting feature of a dementia at all; it could be visuospatial difficulties or apraxia, behavioural problems, or isolated problems with planning. This question of course assumes that the patient can communicate the answer, and it is possible even that the method in which the answer is executed, even if it is nothing to do with memory, reveals a substantial language impairment (for example, the progressive primary aphasias, e.g. Savage et al., 2013). A patient with early Alzheimer’s disease is very likely to report memory problems, in anterograde memory, and the purpose of a brief question of a GP in a busy clinic is to detect at a unrefined way possible glaring “diagnoses” of Alzheimer’s disease. Loss of cognitive function in the elderly population is a common condition encountered in general medical practice, and fairly precise clinical diagnosis is feasible (e.g. Knopman, Boeve and Petersen, 2003). An unfortunate theoretical problem exists that a patient does indeed have memory problems but the patient is unaware of them. In a seminal paper by Starkstein and colleagues (Starkstein et al., 2006), the authors reported on how unawareness of cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease is related might be related the severity of intellectual impairment, a phenomenon known as ‘anosognosia’.

The ideal is that a patient might report memory problems, when probed, but the question suffers from a lack of specificity. In other words, all sorts of people, even if they don’t have dementia, might at first answer “yes!” This inevitably will include what used to be called “the worried well”. Real memory problems could be caused by a whole manner of other conditions, as well as dementia, such as stroke, depression or an underactive thyroid. It could conceivably a “transient global amnesia”, and the exact aetiology of this is currently considered to be uncertain. A mild cognitive impairment (“MCI”) is a clinical diagnosis in which deficits in cognitive function are evident but not of sufficient severity to warrant a diagnosis of dementia (Nelson and O’Connor, 2008). In addition to presentations featuring memory impairment, symptoms in other cognitive domains (e.g. executive function, language, or visuospatial) have been identified. Indeed, in humans, heterogeneity in the decline of hippocampal-dependent episodic memory is observed during aging, and animal models now exist for this phenomenon (Foster, 2012).

There is also a problem that individuals with a dementia syndrome sometimes do not exhibit any memory problems. Indeed, as reviewed by Hornberger and Piquet (2012), over the last twenty years or so, however, the clinical view has been that episodic memory processing is relatively intact in the frontotemporal dementia syndrome; but it is perhaps also worth noting that these authors also note that recent evidence questions the validity of preserved episodic memory in frontotemporal dementia, particularly in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia, a progressive syndrome characterised in its early stages by changes in personality and behaviour, and which indeed gets confused with common adult psychiatric conditions (Pose et al., 2013). It is of course theoretically possible that individuals may have a subclinical form of dementia, where there are no florid memory symptoms for example, but there is an underlying cause (e.g. Morvan’s syndrome, a rare complex syndrome with antibodies to the potassium-channel gated complex producing a dementia involving cognitive problems (Loukaides et al., 2012)), or a paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis producing a dementia (Gultekin et al., 2010). Indeed, in the paraneoplastic dementias, mild cognitive deficits may present before a florid dementia or before the presentation even of the underlying malignancy, for which a full hunt might later then be instigated.

Full-blown screening on a national scale would fundamentally depend on finding a cheap test for finding individuals at risk of later developing the disease. Any quick question is immediately going to run into problems in that dementia is such a wide diagnostic group. Certainly, the question is not sufficient on its own. For example, in an appropriate patient, it might be sensible to ask if the patient has seen things which are not there (in the hope of identifying visual hallucinations as in diffuse Lewy Body Dementia, e.g. Gaig et al., 2011). Even for the most common type of dementia, there is a very active debate whether there might be a reliable prodromal or preclinical phase of Alzheimer’s disease, when changes are taking place even without overt symptoms. Molineuvo and colleagues (Molinuevo et al., 2012), consistent with previous findings, indeed suggest that the preclinical stage is biologically active and that there may be structural changes when amyloid is starting its deposition, reflected in changes in concentrations of markers in cerebrospinal fluid or cortical thickness.

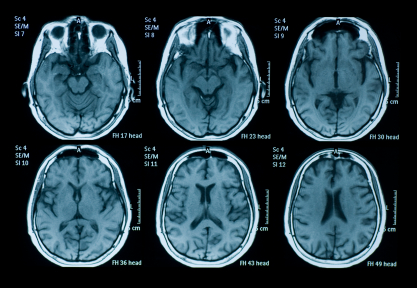

Clearly, investing a lot of time, money and effort in using such techniques currently would be considered impractical in any booming economy (which we do not have), especially given that the cost-impact implications of managing patients with dementia in the community are unclear (Brilleman et al., 2013), and the very modest effects of treatments to improve memory such as the cholinesterase inhibitors have in fact been well known for some considerable time (Holden and Kelly, 2002). It might be attractive to think that MCI is a preclinical form of dementia of Alzheimer Type, but unfortunately the evidence is not there to back this claim up at present: only approximately 5-10% and most people with MCI will not progress to dementia even after ten years of follow-up (Mitchell and Shiri-Feshki, 2009). If one takes the point of view in that the existence of memory symptoms above a certain age might cause ‘alarm bells’ about the need for further investigation, such as specialist opinion about neuroimaging, cognitive psychometry, or even cerebrospinal fluid or brain biopsy (the latter conceivably in the case of cerebral vasculitis or prion disease), such an approach might be worthwhile. However, such a strategy is hugely dependent on the quality of clinicians in primary care and beyond in the NHS, where quality is not a function of economic competition. Quality of dementia care depends on a clinician’s aptitude in taking a targeted history, examination, investigations and management plan.

So, to all intents and purposes, this simple question is dirt cheap, but fails somewhat on specificity and sensitivity. And it all might be pretty innocent enough, if individuals with a genuine diagnosis of dementia are able to access routes enabling them to live well through person-centred care. However, as it is presented, this is potentially a ‘huge ask’ if politicians raise expectations, and do not allocate resources in primary care and specialist dementia and cognitive disorders clinics to match. While the reported underreporting of dementia in the community is not a trivial issue, the demands concerning adequate care of individuals successfully found to be identified with a dementia are likely to be substantial, and for which no convincing impact assessment data have curiously ever been published. Diagnosing lots of dementia might become somebody else’s problem for management if there are inadequate resources; and by that stage this current Government and key personnel might have even moved on, of course.

Please direct comments to Prof @ABurns1907 on Twitter, and not me, if you should like to contribute to this debate. Thank you.

References

Brilleman SL, Purdy S, Salisbury C, Windmeijer F, Gravelle H, and Hollinghurst S. (2013) Implications of comorbidity for primary care costs in the UK: a retrospective observational study, Br J Gen Pract, 63(609), pp. e274-82.

Foster, T.C. (2012) Dissecting the age-related decline on spatial learning and memory tasks in rodent models: N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors and voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in senescent synaptic plasticity, Prog Neurobiol, 96(3), pp. 283 – 303.

Gaig, C., Valldeoriola, F., Gelpi, E., Ezquerra, M., Llufriu, S., Buongiorno, M., Rey, M.J., Martí, M.J., Graus, F., and Tolosa, E. (2011) Rapidly progressive diffuse Lewy body disease, Mov Disord, 26(7), pp. 1316 – 1323.

Gultekin, S.H., Rosenfeld, M.R., Voltz, R., Eichen, J., Posner, J.B., and Dalmau, J. Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis: neurological symptoms, immunological findings and tumour association in 50 patients, Brain, 123 (Pt 7), pp. 1481 – 1494.

Holden, M., and Kelly, C. (2002)) Use of the cholinesterase inhibitors in dementia, Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 8, pp. 89-96.

Hornberger M, and Piguet O. (2012) Episodic memory in frontotemporal dementia: a critical review, Brain, 135 (Pt 3), pp. 678-92.

Knopman, DS, Boeve BF, and Petersen RC. (2003) Essentials of the proper diagnoses of mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and major subtypes of dementia. Mayo Clin Proc, 78(10), pp. 1290-308.

Loukaides, P., Schiza, N., Pettingill, P., Palazis, L., Vounou, E., Vincent, A., aand Kleopa, K.A. (2012) Morvan’s syndrome associated with antibodies to multiple components of the voltage-gated potassium channel complex, J Neurol Sci, 312(1-2), pp. 52-6.

Mitchell, A.J., and Shiri-Feshki, M. (2009) Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia -meta-analysis of 41 robust inception cohort studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 119(4), pp. 252-65.

Molinuevo, J.L., Sánchez-Valle, R., Lladó, A., Fortea, J., Bartrés-Faz, D., Rami, L. (2012) Identifying earlier Alzheimer’s disease: insights from the preclinical and prodromal phases, Neurodegener Dis, 10(1-4), pp. 158-60.

Nelson, A.P., and O’Connor, M.G. (2008) Mild cognitive impairment: a neuropsychological perspective, CNS Spectr, 13(1), pp. 56-64.

Pose, M., Cetkovich, M., Gleichgerrcht, E., Ibáñez, A., Torralva, T., and Manes F. (2013) The overlap of symptomatic dimensions between frontotemporal dementia and several psychiatric disorders that appear in late adulthood, Int Rev Psychiatry, 25(2), pp. 159-167.

Savage, S., Hsieh, S., Leslie, F., Foxe, D., Piguet, O., and Hodges, J.R. (2013) Distinguishing subtypes in primary progressive aphasia: application of the Sydney language battery, Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 35(3-4), pp. 208-18.

The English dementia policy: some personal thoughts

The last few years have seen a much welcome progression, for the better, for dementia policy in England. This has been the result of the previous Government, under which “Living well with dementia: the National Dementia Strategy” was published in 2009, and the current Government, in which the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge in 2012 was introduced.

Dementia is a condition which lends itself to the ‘whole person’, ‘integrated’ approach. It is not an unusual for an individual with dementia to be involved with people from the medical profession, including GPs, neurologists, geriatricians; allied health professionals, including nurses, health care assistants, physiotherapists, speech and language specialists, nutritionists or dieticians, and occupational therapists; and people in other professionals, such as ‘dementia advocates’ and lawyers. I think a lot can be done to help individuals with dementia ‘to live well'; in fact I have just finished a big book on it and you can read drafts of the introduction and conclusion here.

It is obviously critical that clinicians, especially the people likeliest to make the initial provisional diagnosis, should be in the ‘driving seat’, but it is also very important that patients, carers, family members, or other advocates are in that driving seat too. I feel this especially now, given that there is so much information available from people directly involved in with patients (such as @bethyb1886 or @whoseshoes or @dragonmisery) This patient journey is inevitably long, and to call it a ‘rollercoaster ride‘ would be a true understatement. That is why language is remarkably important, and that people with some knowledge of medicine get involved in articulating this debate. Not everyone with power and influence in dementia has a detailed knowledge of it, sadly.

I am very honoured to have my paper on the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia to be included as one of a handful of references in the current Oxford Textbook of Medicine. You can view this chapter, provided you do not use it for commercial gain (!), here.

I should like to direct you to the current draft of a video by Prof Alistair Burns, Chair of Psychiatry at the University of Manchester, who is the current National Clinical Lead for Dementia. You can contact him over any aspects of dementia policy on his Twitter, @ABurns1907. I strongly support Prof Burns, and here is his kind Tweet to me about my work. I agree with Prof Burns that once individuals can be given face-to-face a correct diagnosis of dementia this allows them to plan for the future, and to access appropriate services. The problem obviously comes from how clinicians arrive at that diagnosis.

I am not a clinician, although I studied medicine at Cambridge and did my PhD on dementia there too, but having written a number of reviews, book chapters, original papers, and now a book on dementia, I am deeply involved with the dementia world. I am still invited to international conferences, and I personally do not have any financial vested interests (e.g. funding, I do not work for a charity, hospital, or university, etc.) That is why I hope I can be frank about this. Clinicians will be mindful of the tragedy of telling somebody he or she has dementia or when he or she hasn’t, but needs help for severe anxiety, depression, underactive thyroid, or whatever. But likewise, we are faced with reports of a substantial underdiagnosis of dementia, for which a number of reasons could be postulated. Asking questions such as “How good is your memory?” may be a good basic initial question, but clinicians will be mindful that this test will suffer from poor specificity – there could be a lot of false positives due to other conditions.

At the end of the day, a mechanism such as ‘payment-by-results’ can only work if used responsibly, and does not create an environment for ‘perverse incentives’ where Trusts will be more inclined to claim for people with a ‘label’ of dementia when they actually do not have the condition at all. A double tragedy would be if these individuals had poor access to care which Prof Burns admits is “patchy”. In my own paper, with over 300 citations, on frontal dementia, seven out of eight patients had very good memory, and yet had a reliable diagnosis of early frontal dementia. Prof Burns rightly argues the term ‘timely’ should be used in preference to ‘early’ dementia, but still some influential stakeholders are using the term ‘early’ annoyingly. On the other hand, I wholeheartedly agree that the term ‘timely’ is much more fitting with the “person-centred care” approach, made popular in a widespread way by Tom Kitwood.

I am still really enthused about the substantial progress which has been made in English dementia policy. I enclose Prof Burns’ latest update (draft), and the video I recorded yesterday at my law school, for completion.

Prof Alistair Burns, National Clinical Lead for Dementia

Me (nobody) in reply

Avoiding the rollercoaster: a policy for dementia must be responsible

The last few years have seen a much welcome progression, for the better, for dementia policy in England. This has been the result of the previous Government, under which “Living well with dementia: the National Dementia Strategy” was published in 2009, and the current Government, in which the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge in 2012 was introduced.

Dementia is a condition which lends itself to the ‘whole person’, ‘integrated’ approach. It is not an unusual for an individual with dementia to be involved with people from the medical profession, including GPs, neurologists, geriatricians; allied health professionals, including nurses, health care assistants, physiotherapists, speech and language specialists, nutritionists or dieticians, and occupational therapists; and people in other professionals, such as ‘dementia advocates’ and lawyers. I think a lot can be done to help individuals with dementia ‘to live well'; in fact I have just finished a big book on it and you can read drafts of the introduction and conclusion here.

It is critical obviously that clinicians, especially the people likeliest to make the initial provisional diagnosis, should be in the ‘driving seat’, but it is also very important that patients, carers, family members, or other advocates are in that driving seat too. I feel this especially now, given that there is so much information available from people directly involved in with patients (such as @bethyb1886 or @whoseshoes or @dragonmisery) This patient journey is inevitably long, and to call it a ‘rollercoaster ride‘ would be a true understatement. That is why language is remarkably important, and that people with some knowledge of medicine get involved in articulating this debate. Not everyone with power and influence in dementia has a detailed knowledge of it, sadly.

I am very honoured to have my paper on the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia to be included as one of a handful of references in the current Oxford Textbook of Medicine. You can view this chapter, provided you do not use it for commercial gain (!), here.

I should like to direct you to the current draft of a video by Prof Alistair Burns, Chair of Psychiatry at the University of Manchester, who is the current National Clinical Lead for Dementia. You can contact him over any aspects of dementia policy on his Twitter, @ABurns1907. I strongly support Prof Burns, and here is his kind Tweet to me about my work. I agree with Prof Burns that once individuals can be given face-to-face a correct diagnosis of dementia this allows them to plan for the future, and to access appropriate services. The problem obviously comes from how clinicians arrive at that diagnosis.

I am not a clinician, although I studied medicine at Cambridge and did my PhD on dementia there too, but having written a number of reviews, book chapters, original papers, and now a book on dementia, I am deeply involved with the dementia world. I am still invited to international conferences, and I personally do not have any financial vested interests (e.g. funding, I do not work for a charity, hospital, or university, etc.) That is why I hope I can be frank about this. Clinicians will be mindful of the tragedy of telling somebody he or she has dementia or when he or she hasn’t, but needs help for severe anxiety, depression, underactive thyroid, or whatever. But likewise, we are faced with reports of a substantial underdiagnosis of dementia, for which a number of reasons could be postulated. Asking questions such as “How good is your memory?” may be a good basic initial question, but clinicians will be mindful that this test will suffer from poor specificity – there could be a lot of false positives due to other conditions.

At the end of the day, a mechanism such as ‘payment-by-results’ can only work if used responsibly, and does not create an environment for ‘perverse incentives’ where Trusts will be more inclined to claim for people with a ‘label’ of dementia when they actually do not have the condition at all. A double tragedy would be if these individuals had poor access to care which Prof Burns admits is “patchy”. In my own paper, with over 300 citations, on frontal dementia, seven out of eight patients had very good memory, and yet had a reliable diagnosis of early frontal dementia. Prof Burns rightly argues the term ‘timely’ should be used in preference to ‘early’ dementia, but still some influential stakeholders are using the term ‘early’ annoyingly. On the other hand, I wholeheartedly agree that the term ‘timely’ is much more fitting with the “person-centred care” approach, made popular in a widespread way by Tom Kitwood.

I am still really enthused about the substantial progress which has been made in English dementia policy. I enclose Prof Burns’ latest update (draft), and the video I recorded yesterday at my law school, for completion.

Prof Alistair Burns, National Clinical Lead for Dementia

Me (nobody) in reply