Home » Posts tagged 'patient'

Tag Archives: patient

The World Dementia Council will be much stronger from democratic representation from leaders living with dementia

There is no doubt the ‘World Dementia Council’ (WDC) is a very good thing. It contains some very strong people in global dementia policy, and will be a real ‘force for change’, I feel. But recently the Dementia Alliance International (DAI) have voiced concerns about lack of representation of people with dementia on the WDC itself. You can follow progress of this here. I totally support the DAI over their concerns for the reasons given below.

“Change” can be a very politically sensitive issue. I remember going to a meeting recently where Prof. Terence Stephenson, later to become the Chair of the General Medical Council, urged the audience that it was better to change things from within rather than to try to effect change by hectoring from the outside.

Benjamin Franklin is widely quoted as saying that the only certainties are death and taxes. I am looking forward to seeing ‘The Cherry Orchard” which will run at the Young Vic from 10 October 2014. Of course, I did six months of studying it like all good diligent students for my own MBA.

I really sympathise with the talented leaders on the World Dementia Council, but I strongly feel that global policy in dementia needs to acknowledge people living with dementia as equals. This can be lost even in the well meant phrase ‘dementia friendly communities’.

Change can be intimidating, as it challenges “vested interests”. Both the left and right abhor vested interests, but they also have a strong dislike for abuse of power.

I don’t mean simply ‘involving’ people with dementia in some namby pamby way, say circulating a report from people with dementia, at meetings, or enveloping them in flowery language of them being part of ‘networks’. Incredibly, there is no leader from a group of caregivers in dementia; there are probably about one million unpaid caregivers in dementia in the UK alone, and the current direction of travel for the UK is ultimately to involve caregivers in the development of personalised care plans. It might be mooted that no one person living with dementia can ever be a ‘representative’ of people living with dementia; but none of the people currently on the panel are individually sole representatives either.

I am not accusing the World Dementia Council of abusing their power. Far from it, they have hardly begun to meet yet. And I have high hopes they will help to nurture an innovation culture, which has already started in Europe through various funded initiatives such as the EU Ambient Assisted Living Joint Programmes (“ALLADIN”).

I had the pleasure of working with Prof Roger Orpwood in developing my chapters on innovation in my book “Living well with dementia”. Roger is in fact one of the easiest people I’ve ever worked with. Roger has had a long and distinguished career in medical engineering at the University of Bath, and even appeared before the Baroness Sally Greengross in a House of Lords Select Committee on the subject in 2004. Baroness Greengross is leading the All Party Parliamentary Group on dementia, and is involved with the development of the English dementia strategy to commence next year hopefully.

Roger was keen to emphasise to me that you must listen to the views of people with dementia in developing innovations. He has written at length about the implementation of ‘user groups’ in the development of designs for assistive technologies. Here’s one of his papers.

My Twitter timeline is full of missives about or from ‘patient leaders’. I feel one can split hairs about what a ‘person’ is and what a ‘patient’ is, and ‘person-centred care’ is fundamentally different to ‘patient-centred care’. I am hoping to meet Helga Rohra next week at the Alzheimer’s Europe conference in Glasgow; Helga is someone I’ve respected for ages, not least in her rôle at the Chair of the European Persons with Dementia group.

Kate Swaffer is a friend of mine and colleague. Kate, also an individual living with dementia, is in fact one of the “keynote speakers” at the Alzheimer’s Disease International conference next year in Perth. I am actually on the ‘international advisory board’ for that conference, and I am hoping to trawl through research submissions from next month for the conference.

I really do wish the World Dementia Council well. But, likewise, I strongly feel that not having a leader from the community of people living with dementia or from a large body of caregivers for dementia on that World Dementia Council is a basic failure of democratic representation, sending out a dire signal about inclusivity, equality and diversity; but it is also not in the interests of development of good innovations from either research or commercial application perspectives. And we know, as well, it is a massive PR fail on the part of the people promoting the World Dementia Council.

I have written an open letter to the World Dementia Council which you can view here: Open letter to WDC.

I am hopeful that the World Dementia Council will respond constructively to our concerns in due course. And I strongly recommend you read the recent blogposts on the Dementia Alliance International website here.

Simon Stevens. Is it not where you’ve come from, but where you’re going to?

The new NHS England Chief Executive is Simon Stevens.

Hailed as a ‘great reformer’, the first accusation for Simon Stevens is that he has been parachuted in to change the culture of the NHS. For all the recognition of patient leaders and home-grown leaders in the NHS Leadership Academy, it is striking that NHS England has made an appointment not only from outside the NHS but also from a huge US corporate. Indeed, Christina McAnea, head of health at the union Unison, told the Today programme on BBC Radio 4: “I am surprised that they haven’t been able to find someone within the NHS.”

A person like Stevens is likely to bring a breadth of managerial experiences, although he has never done a hospital job. He is no expert in land economy either. Despite the drama, the transition of the NHS to a neoliberal one has been on a fairly consistent course, as I explained previously in a now quite famous blogpost. I have also discussed how competition was introduced as a major plank in the Health and Social Care Act (2012) despite the overwhelming evidence against its implementation, known at the time; and how the section 75 and associated regulations would be the mechanism to achieve the ‘final blow’ for liberalising the NHS market. Where possibly English health policy experts have failed, perhaps, in their overestimation of the predeterminism that has taken place in England’s health policy since 1997. Changes of government have brought with it various changes in emphasis, such as the Blairite need to ‘reform public services’, possibly away from a socialist centre of gravity. The changing health policy has also had to take on board changes in politics, economics and legal considerations in the last few decades.

The suggestion that NHS England could have chosen ‘a more socialist CEO’ in itself is fraught with criticisms. Can you ‘a bit’ socialist or ‘half socialist’? Indeed, can you implement a ‘socialist NHS’ without implemented a sharing of resources across various sectors, including education or housing? People who don’t wish to engage with such arguments often end up with extremist Aunt Sally arguments referring to socialism as a state like pregnancy or like a religion, but the ideological question still remains can you have state provision of the NHS on a sliding scale from 0-99% private provision? With the current debate about whether Labour would renationalise the railways, in light of the fact that monies are potentially found out of nowhere for foreign military strikes at the drop of a hat, this discussion has never been more relevant potentially. One of David Cameron’s famous phrases, somewhat ironic given his background at Eton and Oxford, is, apparently: “It’s not where you’ve come from – it’s where you’re going to.” This may apply to not only Stevens but the whole of NHS England, especially if you hold the alternative viewpoint that the NHS could and/or should jettison its ‘founding principles’.

It is all very easy to play the ‘man’ not the ‘ball’, and certainly NHS England already has its strategic goals. Nonetheless, it is critically important for any organisation, particularly the NHS, to think about how much of its strategic aims have to be driven from the very top. Attention has turned to the US company he has spent the last decade with as a senior executive: United HealthCare. There is no point, however, being necessarily alarmist. Pro-NHS campaigners will be mindful of this now largely discredited campaign. Resorting to such emotive messaging may distort the genuine discussion which needs to be had about the future of the NHS in England.

Mr Stevens, 47, was Tony Blair’s health advisor between 2001 and 2004, and before that advisor to then-health secretary Alan Milburn. Simon Stevens’ CV reveals that he was a Trustee from The Kings Fund, London (a health charity) between 2007 – 2011 after being a Councillor for Brixton, south London London Borough of Lambeth 1998 – 2002 (4 years). It has even been alleged that Stevens has been a member of the Socialist Health Association. The NHS budget has been notionally protected – it is rising 0.1% each year at the moment – the settlement still represents the biggest squeeze on its funding in its history. Labour has criticised previously how the Coalition has misrepresented the current state of NHS spending. The currently chief executive of the English NHS, David Nicholson, recently called for politicians to be “completely transparent about the consequences of the financial settlements” for the NHS. Nicholson’s point perhaps was that, although politicians say the NHS has been protected financially, this was only relative to real cuts in other areas of government and, crucially, not in terms of the demands on healthcare.

A clue as to how Mr Stevens will run the NHS could be seen earlier this year when he co-authored a report for UHC arguing that the Obama administration could save $500bn in Medicare and Medicaid funding over the next 10 years by more aggressively coordinating medical care for pensioners and the poor. This pitch will have been very attractive to Sir Malcolm Grant. Mr Stevens said instead of concentrating on either cutting benefits or cuts to doctors and hospitals, the US healthcare debate should focus on a “third way”: cutting costs while improving care. A similar challenge awaits him at the NHS. However, the Keogh mortality report identified that safe staffing was a pivotal reason why NHS Trusts had failed un basic patient safety. Stevens is definitely unlikely to find a “third way” between balancing budgets to provide unsafe clinical staffing levels and adequate patient safety.

Some ministers have repeatedly praised Blair’s attempts to reform services, in the earlier period of their administration. In a speech to the Tory party conference earlier this month, Jeremy Hunt highlighted the efforts of Mr Blair and Mr Milburn to increase the use of the independent sector to reduce waiting times. However, Mr Stevens is also associated with the introduction of NHS targets, and helped create the key plan which brought them in. This NHS “target culture” which have been repeatedly attacked by the Coalition as playing a part in scandals such as that at Mid-Staffordshire, as a root cause of the ‘bully boy’ tactics (allegedly) by some NHS CEOs to achieve Foundation Trust and receive personal bonuses. Particularly important then for Labour is not where it has come from but where it is going to.

Andy Burnham MP, Shadow Secretary of State for Health, has repeatedly stated that a Labour Government will repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2012) in its first Queen’s Speech in 2015. It has also been made clear that Labour will do this, even if Burnham is recruited laterally to a different job. For any corporate strategy, a number of drivers will be essential to remember: for example environment, socio-cultural, technological, legal and economics. With the appointment of Stevens “just in time” for the privateers – quite possibly, it is still remarkable that working out the legal niceties of working out ‘mission creep’ in the special administrator powers of NHS configurations is ‘work in progress’. Only this week, it was reported that the Royal Colleges of Physicians have genuine concerns about whether other amendments to the Care Bill are in the patients’ interest, pursuant to the current high-profile mess in Lewisham. Both Stevens and Grant are fully aware that they will have to deal with the political landscape, whatever that is, on May 8th 2015 and afterwards.

Strategic demands of the NHS

Currently NHS England has a number of powerful strategic demands, which could even appear at first blush inherently contradictory. For example, a purpose of patient safety management will be to minimise risk of harm to patients, whereas successful promotion of innovation can be achieved through encouraging risk taking in idea creation. Whatever Stevens’ ultimate vision – and this is why the implementation of Health and Social Care Act (2012) has been so cack-handed – it is essential that industry-acknowledged frameworks for change management are considered at the least. For example, in Kotler’s model of change management, the leader (Stevens) will not only have to ‘create a powerful vision’ but ‘communicate the vision well’.

Patient safety

There is no doubt that the Mid Staffs scandal was a very low point in the NHS. But there’s nothing like a good scandal for focusing the mind? In a general article in June 2009 by James O’Toole and Warren Bennis in the Harvard Business Review (“HBR”), the authors that no organisation could be honest with the public if it’s not honest with itself. This simple principle has been slow to come into the English law, though it has been introduced as an amendment in the Care Bill (2013). A notion has arisen that members of senior management turn a blind eye to failings deliberately (“wilful blindness“), but interestingly the authors draw on the work on Malcolm Gladwell. In his recent book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell had reviewed data from numerous airline accidents. Gladwell remarks, “The kinds of errors that cause plane crashes are invariably errors of teamwork and communication. One pilot knows something important and somehow doesn’t tell the other pilot.” The question is, necessarily, what a CEO can do about it. The authors propose two solutions inter alia. One is to “reward contrarians”, arguing that an organisation won’t innovate successfully if assumptions aren’t challenged. The authors advise organisations, to promote a ‘duty of candour’, to find colleagues who can help, who can be promoted, and who can be publicly thanked. The authors also advise finding some protection for whistleblowers: this might even include people because they created a culture of candour elsewhere. Initiatives such as the Nursing Times ‘Speak Out Safely’ are likely to be highly influential in catalysing a change, but a lot depends on the legal protection for whistleblowers given the current perceived inadequacies of the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998.

There is a growing realisation of implementation of patient initiatives has to be ‘top down’ as well as ‘bottom up’. For example, for Diane Cecchettini, president and CEO of MultiCare Health System, Tacoma, Washington, the key to patient safety has been achieved through leader engagement. She has developed an over-arching strategic framework for quality and safety that has served as the catalyst for the development of multi-year strategic quality and safety improvement plans throughout the MultiCare Health organisation.

Innovation

Innovation is another thorny subject. Innovation (and integration) is always going to be on a dangerous path if primarily introduced as an essential ‘cost cutting measure’, rather than bringing genuine value to the healthcare pathways. Nonetheless, the issue of financial sustainability of NHS England is a necessary consideration, even if the term ‘sustainability’ is open to abuse as I argued previously.

Innovation means different things to different people. As there is no single authoritative definition for innovation and its underlying concepts, including the management of innovation, any discussion on the topic becomes difficult and even meaningless unless the parties to the discussion agree on some common terminology. Innovation requires breaking away from old habits, developing new approaches, and implementing them successfully. It is an ongoing, collaborative process that needs considerable teamwork and skilled leadership. CEOs’ ability to lead their top management team successfully may provide the guidance and inspiration needed to support others to overcome obstacles and innovate. CEOs must provide effective leadership for top management teams to help organizations innovate.

It has been argued that, “There is no innovation without a supportive organisation”. Reviewed in the “International Journal of Organizational Innovation” by de Waal, Maritz, and Shieh (2010), innovation scholars have proposed numerous factors that, to a greater or lesser degree, have the potential to make organisations more conducive to innovation:

- A culture that encourages creative thinking, innovation, and risk-taking

- A culture that supports and guides intrapreneurial liberty and growing a supportive and interconnected innovation community

- Cross-functional teams that foster close collaboration among engineering, marketing, manufacturing and supply-chain functions

- An organisation structure that breaks down barriers to innovation (flat structure, less bureaucracy, fast decision-making, etc.)

- Managers at all levels that support innovation

- A reward system that reinforces innovative and entrepreneurial behaviour

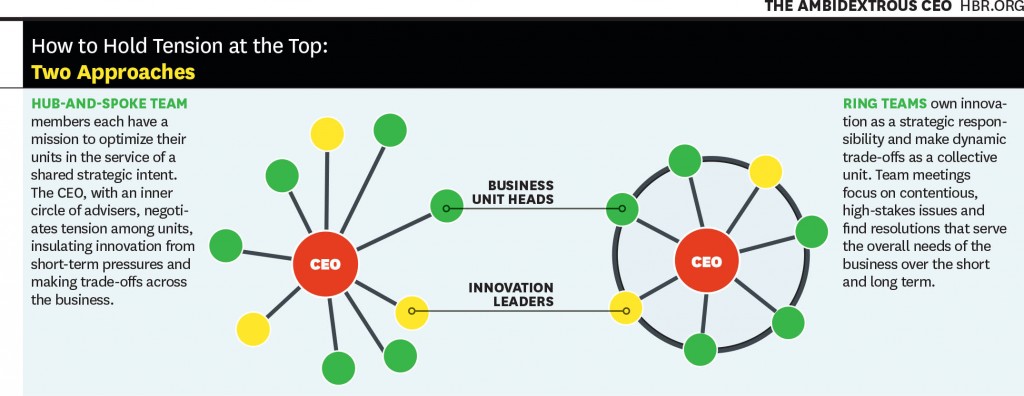

Communicating the vision, as described earlier, is also important for innovation management. This is a potential problem with KPMG’s Mark Britnell’s thesis of how raising the private income cap could promote innovation, as NHS and private wards nearly always co-exist in separate hospitals in ‘NHS Trusts’. It is argued in an interesting article in the Harvard Business Review (2011) entitled, “The ambidextrous CEO”, conflicts in innovation management are best resolved at the very top, and this could be filtered to the rest of the organisation through models such as “hub and spoke”.

It’s probably fair to say that a lot actually rests on the shoulders of CEOs in how innovative they wish their organisation to become. And certainly the ‘high-profile transfer of CEOs’, almost akin to the transfer of footballers, has attracted considerable recent interest, such as Burberry’s Angela Ahrendts joining Apple.

Thomas D. Kuczmarski in a rather sobering paper entitled, “What is innovation? The art of welcoming risk” identifies the CEO even as a potential ‘barrier-to-innovation’ (as far back as in 1996):

If you are like most CEOs, you are in a state of denial. Most CEOs express a fervent belief in new ideas and claim to be committed to innovation, but actions speak louder than words.

The truth is that most CEOs and senior managers are intimidated by innovation. Viewing it as a high-risk, high-cost endeavor, that promises uncertain returns, they are afraid to become advocates for innovation. However, because it clearly represents challenge and opportunity, most CEOs deny their reluctance to embrace innovation. They deny that their new product programs are underfunded or understaffed. They deny that they are closed to new ideas or ways of doing business. They deny that they fail to encourage or reward innovative thinking among their employees. Most of all, they deny that they have created within their organizations a fear of failure that stymies the urge to innovate.

All this denial is not good. It sends mixed messages throughout the organization and sets up the kind of second-guessing and playing politics that can undermine even the best developed business strategies. Unwilling to be measured by their failures, employees are reluctant to take risks that the successful development of new ideas demands and, as a result, even the desire to innovate diminishes.

Stevens (2010) himself has publicly expressed concerns on failure to innovate. For example, in the Harvard Business Review, he discussed how information on new clinical treatments spreads across the world quite fast, and how healthcare systems which fail to be flexible enough on picking up on this are likely to fail. Stevens’ example is striking:

However, the rate at which innovations are being translated into actual improvements is agonizingly slow — a frustrating problem that dates back to the world’s first controlled clinical trial in 1754. It proved that lemons prevented sailors from getting scurvy, but it then took another 41 years for a navy to act on the results. Wind the clock forward to today, and 15 years or so after e-mail became common, it turns out that most patients still can’t communicate with their doctors that way.

Deutsch (1973, 1980) proposed that how individuals consider their goals are related, very much affects their dynamics and outcomes. The basic premise of the theory is that the way goals are structured affects how people interact and the interaction pattern affects outcomes. Goals may be structured so that people promote the success of others, obstruct the success of others, or pursue their interest without regard for the success or failure of others. Deutsch identified these alternatives as cooperation, competition, and independence. In cooperation, people believe that as one person moves toward goal attainment, others move toward reaching their goals. They understand that others’ goal attainment helps them; they can be successful together. In competition, people, believing that one’s successful goal attainment makes others less likely to reach their goals, conclude that they are better off when others act ineffectively. When others are productive, they are less likely to succeed themselves. They pursue their interests at the expense of others. They want to ‘win’ and have the other ‘lose’. With independent goals, people believe that their effective actions have no impact on whether others succeed. Researchers have long debated whether cooperation or competition is more motivating and productive (Johnson, 2003). As regards the thrust of what happens in reality following 2015, therefore, the political landscape does very much happen. If Labour wish to promote collaboration perhaps through integration of health and social care, the entire nature of this dialogue will change. And the new CEO of NHS England will have a pivotal rôle in the organisational learning of the whole of NHS England.

Further implications for Labour in general policy

Some further issues are raised by Stevens (2010) short piece for the HBR. Labour has begun to ‘apologise’ for accelerating progress in the market of the NHS.

Introducing the ‘fair playing field’ of the market – another bogus concept which has gone badly wrong

The policy of ‘independent sector treatment centres’ under Labour has been much discussed elsewhere. PFI, although originally a policy which arose out of David Willett’s pamphlet for the Social Market Foundation (“The opportunities for private funding in the NHS“), and in the Major Conservative administration (see the work of Michael Queen), has seen various reformattings itself during successive Labour (Brown/Blair) and Conservative governments (Osborne/Cameron). The issue is that failing Trusts are not big to fail, unlike banks. Trusts ‘going bust’ are open to asset stripping from the private sector.

The opening up of the market is encapsulated in the document from Monitor, “A fair playing field for NHS patients”. Increasing the number of market providers not only potentially boosts ‘competition’ in the market, but also produces a supply of ‘predators’ in the terminology of Ed Miliband’s much maligned conference speech in Liverpool in 2011. This conference speech nevertheless successfully signposted with hindsight the highly celebrated political notion of ‘responsible capitalism‘. Many on the left now view the concept of ‘a fair playing field’ as being entirely bogus with the onset of decisions being made in the NHS on the basis of competition law not clinical priorities.

To what extent Burnham will wish to make a break from the past is the crux of the issue. Having signalled that he wishes to repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2012) is the beginning of a long journey. At some stage, there will be a debate again about how much of the NHS is actually funded out of taxation, or whether, as anti-privatisation campaigners fear, whether we need to re-consider the explosive issue of co-payments or subsidiary payments. Burnham has signalled that he wishes to implement a NHS ‘preferred provider’ policy, in trying to capture lost ground on the increase in private provision in the NHS. But even here he may run into difficulty if legally the US-EU Free Trade Treaty, with discussions currently underway, make it impossible for him to implement such a policy.

But as it is, injecting ‘competition’ into the system could be in fact be the sort of competition which has dramatically failed in the energy sector. It is noteworthy that Ed Miliband has decided to whip himself up into a frenzy publicly about this in parliament, as part of the #costoflivingcrisis, rather than adopting the technocratic bureaucratic approach of waiting for the Competition Commission to investigate this particular market. It is well known that encouraging new entrants to the healthcare markets, even in the third sector, is fraught with difficulties, with the market occupied by a few well-known private sector brands. Here, the scandal of what are high prices, unlike ‘energy’, may remain a hidden scandal, as the customer is not directly the patient: it is the clinical commissioning group.

What do CCGs actually do?

Andy Burnham, to emphasise that he is not going to embark on yet another costly disorganisation in 2015, has explained that he intends to make the existing structures ‘do different things’. However, there is currently a bit of muddle as to what CCGs actually do.

Stevens states that:

Consolidation among care providers and barriers to entry for new hospitals mean that health-care delivery mostly relies on incumbents doing a bit better, as opposed to step changes in productivity from new entrants. Yet in the rest of the economy, new entrants unleash perhaps 20% to 40% of overall productivity advances.

Of course, with Stevens having leaving the NHS after ‘Blair times’, United Health has been set to become one of the beneficiaries of the advancing liberalisation of the NHS market.

It is now becoming more recognised that CCGs are in fact state aggregators of risk, or state insurance schemes. I had the opportunity recently of asking Sir Malcolm Grant in an exhibition at Olympia whether he had any disappointment that clinicians were not leading in CCGs as much as they could be, and of course he said “yes”. But strictly speaking GPs do not ‘need to’ lead CCGs as they are insurance schemes. The notion of ‘GP-led commissioning’ is widely felt to be a pup which was usefully actioned by the media to sell the controversial recent NHS reforms to a suspicious public.

This may or may not be what Stevens feels, albeit Stevens was speaking from the position of senior management in an aggressive US corporate at the time:

Increasingly, health plans should look to become ‘care system animators’ and not merely risk aggregators and transactional processors. Using their population health data, their information on clinical performance, their technology platforms, and their ability to structure consumer and provider-facing incentives, health plans have enormous potential to help improve health and the quality, appropriateness and efficiency of care. At UnitedHealth Group, our new Diabetes Health Plan, new telemedicine program, new eSync technology, and work on new models of primary care are all examples of what this can mean in practice.

Conclusion

In a perverse way, Stevens has an opportunity now to make the NHS work using knowledge of what the private sector does best and worst, in the same way that he was able to take advantage of his NHS policy knowledge while working for United Health. To what extent he will be concerned about the shareholder dividend of private companies as the NHS buggers on regardless will be more than an academic interest. No doubt the media will follow Stevens’ share interests with meticulous scrutiny.

The extent to which, however, he as the CEO can mould the culture of the NHS is an interesting one, however. If he (and ministers) believe that that it is he who should be leading change, then his default pathway will be one of private sector organisational change, with focus on patient safety and innovation through leadership. He will, however, run into problems if the NHS becomes primarily stakeholder-led. In other words, if patient campaigners continue to advocate that “patients come first“, especially through successful campaigning on patient safety or patient-led commissioning, Stevens might find his task is much harder than being a CEO of an American corporate.

Simon Stevens may seem like a powerful man. But there could be a man who is even more powerful from May 8th 2015, who might have a final say on many areas of policy, ahead of Stevens and Grant.

And that man is @andyburnhammp.

References

Birk, S. (2009) Creating a culture of safety: why CEOs hold the key to improved outcomes. Healthcare Executive (Mar/Apr), pp. 14-22.

de Waal G. A, Maritz P.A, Shieh C.J.(2010) Managing Innovation: A typology of theories and practice-based implications for New Zealand firms, The International Journal of Organizational Innovation 01/2010; 3(2):35-57.

Deutsch, M. (1973). The Resolution of Conflict. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Deutsch, M. (1980). ‘Fifty years of conflict’. In Festinger, L. (Ed.), Retrospections on Social Psychology. NewYork: Oxford University Press, 46–77.

Johnson, D. W. (2003). ‘Social interdependence: interrelationships among theory, research and

practice’. American Psychologist, 58, 934–45.

Kuczmarski, T.D. (1996) What is innovation? The art of welcoming risk, Journal of Consumer Marketing, 13(5), pp. 7-11.

Stevens, S. (2010) How Health Plans Can Accelerate Health Care Innovation, available at:

http://blogs.hbr.org/2010/05/how-health-plans-can-accelerate/

Toole, J.O., Bennis, W. (2009) What’s needed next: a culture of candor, Harvard Business Review, June edition, pp.54-61.

Tushman, M.L., Smith, W.K., Binns, A. (2011) The ambidextrous CEO, June, pp. 74-80.