Home » Posts tagged 'neoliberalism'

Tag Archives: neoliberalism

Now it is clear that patients must be offered real choice – at the ballot box

What brand of washing powder would Sir like?

Nobody really has a need for a thousand different types of washing powder, unless it happens to be the case that you’re physically allergic to particular brands. And similar arguments can be put forward for gas and water. Or a hernia operation.

Will the patient be aware that he has a particular congenital abnormality in his tummy wall requiring his surgeon to go in a particular route to repair his umbilical hernia?

It is hard to see how this constitutes patient choice. And also, if the market agrees amongst itself, certain providers will do the hernias, and others will do the excision of sebaceous cysts, how much choice will there be if a number of large providers settle on a ‘market price’ for these services? However, the service is essentially the same.

People who support ‘choice’ by and large say that it is not a matter of ideology, but paradoxically then continue to talk about choice as a matter of a human right. But choice must be meaningful. Choice cannot be properly exerted if you are in fact being sold a pup literally. Or it can’t be true choice if the money has run out – money doesn’t grow on trees, remember.

With the main political parties converging on various forms of the market, personal health budgets, the need for ‘efficiency savings’ (even if that leads to dangerous unsafe staffing while PFI loan repayments are made), an assumption of continued unnegotiated PFI contracts, how much choice does the electorate have?

Presumably Labour will continue to campaign on its ‘Only Labour can save the NHS’ meme, and looking around there is some justification of this with the firestorm closure of accident and emergency units here in London.

But whichever party comes into power, the question has to be: will very much change?

Personal health budgets are an extremely good example of this. The main political parties continue to tout this policy plank, with the continued maelstrom of ‘success stories’ as well as severe warnings. And yet nothing much seems to change.

The same providers promote them. The same campaigners oppose them.

Like any proposed European referendum, it is hard to know whether many members of the general public are in charge of the real facts – such as whether there are important safeguarding issues to protect people with certain types of dementia? Or to prevent people going through a manic phase of bipolar affective disorder to go through a phase of reckless manic spending?

I feel that all parties must now accept that many voters do feel severely disenfranchised, and it is hard to know how remedy this information asymmetry without, say, doing a LBC debate presented by Nick Ferrari or a BBC debate presented by David Dimbleby.

But the tragedy remains, that while we keep on being told that ‘choice is good for us’, the scope for real choice, many say being an attribute of neoliberal multinational corporate activity, is a phoney one.

The NHS needs an innovative ‘blockbuster’ now. That is to be brought back under the State.

The term “innovation” must be one of the most misused terms in the media. It simply means a different way of doing things, such as a product or a service, whose popularity and effectiveness ultimately govern its success.

And yet the term has been strikingly bastardised to be used in conjunction with a whole plethora of memes such as “ageing”, “technology” and “unsustainable”. The right wing has been consistently ‘on message’ in this script.

Ed Miliband in Manchester gave last night what was a perfectly plausible speech on the NHS last night. Excerpts of it have indeed been posted on our blog. And there was the usual ‘red meat’, to be accompanied at some later date by how realistic the costings are.

But the legitimate concern of voters, whether hardworking or not, is he who pays the piper calls the tune. It may not be the frontline staff with whom Ed Miliband had photo opportunities earlier this week.

Fifty shades of government, apart from green, have been obsessed with inflicting ‘transformative’ changes, perhaps ‘charismatic’ visions, without ever consulting the wider population. Examples include the private finance initiative, or ratcheting up the NHS into a competitive market.

But Nigel Farage, whether or not he is ‘establishment’, has struck a chord with some voters. I don’t mean with his allegedly racist twangs, but I mean his ‘trust the voter’ skit. He bangs on about the referendum which he knows will never see the light of day.

Labour’s argument for why the NHS needs private companies working for it remains unconvincing with many voters. That’s why the National Health Action Party or the Green Party are watched so keenly by many.

The argument is possibly not as complicated as that justifying our membership of the European Union, but it is one which is best left to the voters to justify.

Labour in pursuing its ‘35% strategy’, where it can squeeze into office on the back of disaffected Liberal Democrat voters, is by definition risk averse. But with taking low risks the return can be very low. Labour’s lack of “blockbuster” is potentially alarming.

And many of the arguments can be discussed under the assumption that GPs work for the NHS. The BMA’s “#YourGPcares” campaign is calling for long-term, sustainable investment in general practice now to attract, retain and expand the number of GP, expand the number of practice staff, and improve premises that GP services are provided from.

The pitch for state ownership is pretty basic. Ed Miliband MP, Leader of the Labour Party, yesterday Labour’s new GP guarantee as part of the next government’s plan to improve services for patients, ease the pressure on hospitals, and restore the right values to the heart of the NHS.

Speaking in Manchester, he underlined his determination to put the health service at the centre of Labour’s campaign over the next year, beginning with these local and European elections.

But it feels as if Ed Miliband is making a meal lacking the key ingredients.

Andy Burnham MP’s ‘NHS preferred provider’ is conspicuous by its absence in the speech.

Only once Ed Miliband has slain this dragon, he can be given to talk about how primary care is best delivered. Labour is aware of its history of “polyclinics” first proposed by Professor the Lord Darzi of Denham in his review of healthcare in London for NHS London “Healthcare for London: A Framework for Action”.

The Labour Government at the time argued that this was a way of providing more services in the community closer to home and at more convenient times (including antenatal and postnatal care, healthy living information, community mental health services, community care, and social care and specialist advice).

Ed Miliband seems to care about ‘privatisation of the NHS’, in that he cared to mention ‘ending’ it.

But this is again at odds with what Simon Stevens has been thinking about.

A “Free School” is a type of Academy, a State-funded school, which is free to attend, but which is not controlled by a Local Authority.

Like other types of academy, Free Schools are governed by non-profit charitable trusts that sign funding agreements with the Secretary of State.

Supporters of Free Schools, such as the Conservative Party, including that they will “create more local competition and drive-up standards” They also feel they will allow parents to have more choice in the type of education their child receives, much like parents who send their children to independent schools do.

But Ed Miliband also talking about ‘ending competition’ which is somewhat against the mood music Simon Stevens was singing in his appearance against the Commons Select Committee.

It’s innovative bringing something back into state control, but could make good ‘business sense’, akin to insourcing a service which had been previously outsourced.

The main arguments for state control and ownership of the NHS are that such a drive would encourage co-operation, collaboration, equity; services could be properly planned not fragmented; and services would not be run for shareholder dividends.

It’s undoubtedly true that there could be operational changes to be made, such that patients could plan their GP appointments without having to ring up as an emergency at 8.30am the same day.

NHS GPs overall say that they are working flat out, and, short of having greater resources, no political gimmick will help them. Instead of lame slogans such as “Hardworking Britain Better Off”, and making do with “35%”, Labour could do something really innovative – and return to a socialist approach.

‘Saving the NHS for the public good’, on the other hand, is not a vacuous gimmick. It’s what many people in Labour also believe, possibly. More importantly, it’s the title of a current party election brodcast by the Green Party. It might be the case that Ed Miliband is left wing than the Labour Party membership. This has been mooted here. If so, “bring it on!”

The Right needs to make up its mind: is society, or the individual, more important?

Socialism has never been clearer.

We not consider the State to be a ‘swear word’. We are proud of our values of solidarity, social justice, equality, equity, co-operation, reciprocity, and so it goes on.

The Right, meanwhile, needs to make up its mind: is “societal benefit” more important, or the individual?

The rhetoric under Margaret Thatcher and beyond, including Tony Blair, was individual choice and control could ‘empower’ individuals. This was more important than the paternalistic state making decisions on your behalf, and indeed Ed Miliband was keen to read from the same script at the Hugo Young lecture 2014 the other week.

Yet, the phrase “societal good” has been used by an increasingly desperate Right, wishing to justify money making opportunities in caredata, or cost saving measures such as NICE medication approvals or hospital reconfigurations, So where has this individual power gone?

Whilst fiercely disputed now, Thatcher’s idea that ‘there is no such thing as society’ potentially produces a sharp dividing line between the rights of the individual and the value of society.

“There is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women, and there are families. And no government can do anything except through people, and people must look after themselves first. It is our duty to look after ourselves and then to look after our neighbour.

was an individualist in the sense that individuals are ultimately accountable for their actions and must behave like it. But I always refused to accept that there was some kind of conflict between this kind of individualism and social responsibility. I was reinforced in this view by the writings of conservative thinkers in the United States on the growth of an `underclass’ and the development of a dependency culture. If irresponsible behaviour does not involve penalty of some kind, irresponsibility will for a large number of people become the norm. More important still, the attitudes may be passed on to their children, setting them off in the wrong direction.”

(M. Thatcher, Woman’s Own, October 31, 1987)

Whilst the Left has been demonised for promoting a lethargic large State, monolithic and unresponsive, there’s been a growing hostility to large monolithic private sector companies carrying out the State’s functions.

It is alleged that some of these companies are not doing a particularly good job, either.

It has recently been alleged that the French firm, ATOS, judged 158,300 benefit claimants were capable of holding down a job – only for the Department of Work and Pensions to reverse the decision. At the end of last year, private security giants G4S and Serco have been stripped of all responsibilities for electronically tagging criminals in the wake of allegations that the firms overcharged taxpayers

So why should the Right be so keen suddenly on arguments based on ‘societal benefit’?

It possibly is a cultural thing.

The idea that “large is inefficient” was never borne out by the doctrine of ‘economies of scale’, which is used to justify the streamlining of operational processes across jurisdictions for multinational companies.

This was a naked inconsistency with the excitement in corporate circles with “Big Data”, that big is best.

Many medical researchers are rightly excited at the prospect of all this data. Analysis of NHS patient records first revealed the dangers of thalidomide and helped track the impact of the smoking ban. This new era of socialised big NHS data could be very powerful indeed. Whilst there were clearly issues with informed consent at an individual level, the argument for pooling of data for public health reasons were always compelling.

The fact that this Government is simply not trusted when it comes to corporate capture has strongly undermined its case. Also, if the individual must put itself first, why should he allow his data to be given up? Critically, this knowledge doesn’t just have a social good, or multiple individual health ones. It has economic value too.

It might simply be that the Right is keen on this policy through now is precisely because such data will offer significant financial benefits, and that any to wellbeing are simply pleasant side-effects. The concern that this policy is actually about boosting the UK life sciences industry, not patient care. This is science policy – where science lies within the technical jurisdiction of the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills – not just health policy.

Is it not reasonable that an individual should have the right to opt out of having his caredata being absorbed?

“Societal good” has been used by the current Government in a different context too.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) will consult next month on an update to its methodology for assessing drugs. It had been asked by the Department of Health to make judgments on the “wider societal benefit” of medicines before recommending them for NHS use. But a board meeting this week has decided it would be wrong to make an assessment that effectively would put a monetary value on the contribution to society of the people likely to be taking the drugs.

It is thought that any assessment of “wider societal benefit” would inevitably end up taking age into account, say papers from the meeting. “Wider societal benefit” could therefore be simply an excuse for excluding more costly older patients.

NICE’s chief executive, Sir Andrew Dillon, has said it is valid to take into account the benefit to society of a new drug, but great care had to be taken in the way it was done, so that an 85-year-old was not regarded as less important than a 25-year-old. One group of patients should never be compared with another.

But an older individual must put his access to medications first surely?

A legal challenge brought by the local authority and the Save Lewisham hospital campaign showed conclusively that the secretary of state did not have the power to include Lewisham in a solution to the problems of SLHT.

As Caroline Molloy explains:

“The hospital closure clause gives Trust Special Administrators greater powers including the power to make changes in neighbouring trusts without consultation. It was added to the Care Bill just as the government was being defeated by Lewisham Hospital campaigners, in an attempt to ensure that campaigners could not challenge such closure plans in the future. But the new Bill could be applied anywhere in the country.”

Clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), the groups of state representatives making local health plans about resource allocations, will still need to be consulted in this process, and the consultation has been extended to 40 days. However, disagreements between CCGs may now be overruled by NHS England. So, the most important local decision makers may have no say in key reconfigurations of their hospitals and care services.

An individual within a locality must surely have the right to put his own interests regarding social provision first?

I believe that part of the reason the Right has got into so much trouble with caredata, access to drugs and clause 118 is that it appears in fact to ride roughshod over people’s individual rights, and in all three cases is only considering the potential economic benefit to the budget as a whole. They are not interested in the power of the individual at all.

And the most useful explanation now is actually that with such overwhelming corporate capture engulfing all the main political parties, that there’s no such thing as “Left” and “Right” any more. It might have been once our duty to look after ourselves, but it is clear that conflicts have emerged between individual autonomy and the needs of the corporates.

The “Right” is not actually working for the needs of the individual at all, nor of society.

The most parsimonious reason is that the Right is not as such a Right at at all. It, under the subterfuge of being “centre-left” or “centre right”, is simply acting for the needs of the corporates, explaining clearly why so many are disenfranchised from politics. From this level of performance, the Right has not only failed to safeguard the interests of the Society, it has failed to uphold the rights of the individual. This is an utter disgrace, but entirely to be expected if the Government governs on behalf of the few.

Of course we knew that this would happen under the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats, but Labour needs to return to democratic socialism urgently.

For flood victims, the State is not a dirty word. So why should it be for patients of the NHS?

Ironically, just as Ed Miliband gave his Hugo Young 2014 lecture on “an unresponsive State”, many people in the SW England saw their sandbags being delivered to a different location.

The floods have revealed what many of us have suspected all along.

The response to the floods has revealed a painful fault line in our narrative of ‘The State’.

There’s no COBRA meeting when fourteen Trusts run into difficulties with patient safety, because of the common thread that they don’t have a safe minimum level of safe staffing.

The acute general medical take for many health professionals is a ‘firefighting experience’, with the aspiration of lean management to mean there’s actually insufficient capacity in the system to cope with increased demand.

It is now being reported that some British insurers are unwilling to take on the risks of certain flood areas, feeling that the market is somehow rigged towards only benefitting “cherrypickers”.

It makes us wonder who the postman will be, now that Royal Mail is privatised benefitting hardworking hedgies.

And yet this is precisely the criticism that anti-privatisation campaigners on the NHS have been saying since initial discussions of the Health and Social Care Bill (2011) commenced.

The market is unable to guarantee complete coverage for all scenarios. In the case of private insurance and health, rarer ‘unprofitable’ diseases will just become out of scope. Like Owen Paterson’s ‘badgers’, the location of the goalposts will be redefined so that some NHS interventions are no longer ‘necessary’.

David Cameron’s response curiously has not been to resuscitate his flagship turkey.

You would have thought, if you believed any of Steve Hilton’s hype, that people would fight them in the dinghies as a “Big Society” response.

Or somehow the market could be “nudged” into action, where the market could be realigned with financial incentives to make us want to give a shit about our fellow man or woman now underwater.

Instead, David Cameron has been trying to fatten up the impoverished State.

If you think that the current debate about the actual fall in NHS spending is going nowhere, that’s clearly small change compared to what may or may not been happening to Lord Smith’s Environmental Agency.

For flood victims, the State is not a dirty word (save for those victims who feel profoundly let down by the lack of response by the State). So why should it be for NHS patients?

It’s well known that the current Government considered implementing an insurance-based system but eventually went against it. The implementation of personal budgets has been progressing over the few years, with rather little discussion.

And yet, personal budgets could become a major plank of Labour’s “whole person care”. Somewhat reminiscent of ‘expert commentators’ who were slow on the uptake when it came to uptake on competition in section 75, they appear equally sleepy on the significance of unified budgets for health and social care.

From one perspective, they ‘empower’ persons, and give them ‘choice’. But from another perspective, they actually disempower persons when the State runs out of money, and you have to top up your budgets from some other means.

It’s this two tier nature which causes the most alarm. Already, there’s been much finger pointing about ‘personal responsibility’ of people building homes knowingly on flood plains. The shift of potential blame as well as shift in personal responsibility is a deliberate change of emphasis in policy, and one which Labour must have an open discussion about if it wishes to retain any vestiges of trust.

The whole basis of trust of the public has for some time taken a knocking, with implementation of the private finance initiatives (PFI) and discussion of caredata.

While budget sheets are in the hock of paying off loan repayments, rather than paying for much needed staff to take the level of staffing beyond ‘skeleton’ or ‘extra lean’, the talk about a ‘more responsive State’ is all fluff.

While the NHS complaints system remains unfit for purpose, it’s all fluff.

It may be the fluff which keeps Alan Milburn and Tony Blair happy, but, despite the three general election victories, it has been a policy issue which Labour must revisit.

Proper levels of funding of the NHS and social care have long been popular and populist policies for Labour, and so has effective State planning.

It remains thus all the more strange that the only State that the Labour Party in fact cares about is the Square Mile.

The NHS and markets – the drugs don’t work

This week, David Cameron MP mocked Ed Miliband MP for sounding like a person who’d rung up a radio show whingeing.

Cameron replied, “And your problem is caller?”

The problem is a complete collapse of ideological position which has lasted decades.

Ed Miliband keeps up the moment today with the market failure of the energy oligopoly (see article by Patrick Wintour in the Guardian.)

It is argued that one of the precursors of Thatcherism was a revival of interest in Britain and worldwide in the work of the Austrian economist and political philosopher, Friedrich Hayek, who won the Nobel Prize for economics in 1974.

Alongside Milton Friedman, who won his Nobel Prize in 1976, Hayek lent great prestige to the cause of economic liberalism, helping to create the sense of a rightward shift in the intellectual climate, complementing the approach of Ronald Reagan across the pond.

These principles of dogma have seen successive Conservative and Labour governments reaching for the drug of privatisation and outsourcing.

But these drugs are not only failing to work. They are having devestating side effects which are killing the patient.

The markets have been outed for being far from liberalising. They create inequality. It is alleged that the austerity-based policies have led to a marked decline in mental health and rates of suicide even.

But it’s not the shocking Gas bill which has delivered the knock-out blow for the Conservatives’ religion.

“Here is the reality. This is not a minor policy adjustment—it is an intellectual collapse of the Government’s position.”

This was Ed Miliband’s verdict in Wednesday’s Prime Minister’s Questions.

Only a day previously, BBC Radio 4’s had played a voxpop of various members of the public speaking about ‘payday loans’ as a prelude to interviewing George Osborne MP.

“I don’t accept it’s a departure from any philosophy. The philosophy is we want markets to for people. People who believe in the markets like myself want the market regulated. The next logical step is to cap the cost of credit. It’s working in other countries. In fixing the banks, we need to fix all parts of the banks and the banking system. It helps all hard-working people.”

During the time of the previous Labour government, the King’s Fund was head-over-heels promoting competition.

It was known that, by shoehorning competition as a policy, private providers would make a killing.

All you had to do was to bring in a £3bn ‘top down reorganisation’, a 500 page Act of parliament containing no clause on patient safety apart from the abolition of the National Patient Safety Agency, and beef up a new consumer regulator (“Monitor”).

But meanwhile back to payday lending, an evidenced case of market failure.

“We’ve always believed in properly regulated free markets, where there’s competition, but where the market is properly regulated. That’s why we created a new consumer regulator.”

Far from being a loveable buffoon Boris Johnson, Johnson has revealed himself to be the toxic political mess he is.

Suzanne Moore, at the risk of being hyperbolic, called out Johnson as ‘sinister’.

Johnson had launched this week a bold bid to claim the mantle of Margaret Thatcher by declaring that inequality is essential to fostering “the spirit of envy” and hailed greed as a “valuable spur to economic activity”.

In an attempt to shore up his support on the Tory right, as he positions himself as the natural successor to David Cameron, the London mayor called for the “Gordon Gekkos of London” to display their greed to promote economic growth.

He qualified his unabashed admiration for the “hedge fund kings” by saying they should do more to help poorer people who have suffered a real fall in income in recent years.

And what’s wrong with greed being good if this improves patient care in the NHS?

The issue always remains ‘zero sum gain’. It’s a problem as it diverts tax-funded resources directly in the coffers of the private sector.

Arguably, it’s not just the failure of the market which is the problem, but ‘the undeserving rich’ who have never ‘seen it so good’ since Tony Blair’s New Labour period of government.

In August 2009, the then leader of the Opposition and Conservative leader, David Cameron, MP defended a shadow health minister for advising a firm which offers customers an alternative to NHS doctors.

Lord McColl was on the advisory board of Endeavour Health, which promised a quick and convenient access to a network of “top” private GPs.

It was claimed then that Endeavour Health is a company set up by two hedge fund advisers which purported to be Britain’s first comprehensive private GP network.

In a video yet to be deleted off You Tube, David Cameron argued that there was nothing ‘improper’.

This was interpreted at the time that the Conservatives “favoured private alternatives”.

Nonetheless, David Cameron claimed that the Conservatives was ‘totally dedicated to the NHS’, but he wished ‘to expand the NHS so that people don’t have to use the private sector’.

What actually happened was the Health and Social Care Act (2012).

In July 2013 in the British Medical Journal, it was reported that the private sector is in line to secure hundreds of millions in NHS funding from services placed out to the open market under the UK government’s latest competition regulations, a study has shown.

Research by the pressure group the NHS Support Federation found that contracts for around 100 NHS clinical services totalling almost £1.5bn (€1.7bn; $2.2bn) have been advertised since 1 April 2013, with commercial companies winning the lion’s share of those awarded to date.

Data from official tenders websites showed that only two of 16 contracts awarded since the government’s section 75 regulations of the Health and Social Care Act came into force have gone to NHS providers, with the remaining 14 going to the private sector.

A few days ago, it was reported tonight that David Cameron is intending to ban branded cigarette cartons, having originally decided last July not to proceed with the plans.

In the summer the Government said it was waiting to see how plain packaging worked in Australia, which introduced the measures a year ago, before making any changes. It has since maintained it is monitoring the situation.

That is the spin. Behind the scenes, it is well known that tobacco corporates have throttled public health policy.

In the third volume of Law, Legislation and Liberty, Hayek argued that there are not two but three kinds of human values: those that are “genetically ordered and therefore innate”; those that are “products of rational thought”; and values that had triumphed in the course of cultural evolution by demonstrating their suitability to the successful organization of social life.

Hayek believed that these values were a cultural inheritance, survivors of a competitive struggle, and essential conditions for the successful evolution of our society.

David Cameron is indeed right to be worried.

There has been a collapse of the ideological position that he and his predecessors, Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair, stood for.

This is in relation to the markets.

This fundamentally changes the terms of reference for a market-based NHS.

Contagion is likely politically.

If payday lending or the energy markets are anything to go by, there could be trouble ahead.

So what’s the issue? The caller’s problem is that “the markets don’t work”, “they only make you feel worse again”.

And now the caller’s finally worried about the NHS.

It’s the Equality stupid…

“The Conservatives lead on the economy”

“Labour is ahead on the NHS”

These appear to be the laws of nature of political philosophy in the UK.

And yet Ed Miliband has managed successfully to rearticulate the debate about the economy from the deficit to ‘what’s in it for me?’.

Ed Miliband wants the ‘squeezed middle’ to think that things have got much worse for them, with the cost-of-living far outstripping incomes, while the ‘super rich’ are happy on champagne on caviar.

Joking apart – the next general election, which will be intensively fought – will be dominated by the ‘cost of living crisis’, but the competence of the Conservative Party on the NHS (and their general approach to it) will be a factor.

Most people remember the famous sign in the Clinton campaign war room in 1992 as “It’s the economy stupid!” But what is often forgotten is the second phrase in the famous warning by Carville to Clinton campaigners to keep a sharp focus on the campaign’s message: “And don’t forget health care.” Andy Burnham MP now on numerous occasions has reminded supporters of this, including his fringe meeting for the New Statesman magazine in Manchester in 2012.

It’s obvious that Labour wishes to focus more on equality – or lack thereof.

Equality is more of a defining value in the Labour government than the liberal or social democratic philosophies, many believe. It is often politely derided in a textbook way, as by Michael Gove recently in a discussion of ‘One Nation’, as being rather ludicrous in that the Left appears to want to ‘force’ people to be equal.

Perhaps due to the rejection of “In place of strife” by a previous Labour government, the dying days of the Callaghan Labour administration was crippled by the activities of the Unions. The Conservatives hope that sufficient numbers of people will remember this misery from the 1970s to wish that a Labour government is never returned. That is why the “leveraging inflatable rat” is of such totemic political importance.

David Cameron has therefore vowed to crush Ed Miliband’s ‘1970s-style socialism’ as he put tax cuts, enterprise and opportunity at the heart of an election campaign to reprise the Tories’ defeat of Neil Kinnock. Cameron has condemned Labour’s ‘damaging, nonsensical, twisted economic policy’ and scoffed at what he called ‘Red Ed and his Blue Peter economy’ – saying it would heap ruin on Britain.

He has therefore asked the general public for the Conservatives “to continue the job” – not of continuing to stagnate the recovery, but to allow the UK economy to recover under his watch.

However, as Matthew d’Ancona observed today, the election of Bill de Blasio as New York’s 109th mayor is perhaps far beyond Manhattan and the Bronx. Campaigning against Michael Bloomberg’s 11 years in office as “a tale of two cities”, de Blasio easily won against his Republican rival, Joe Lhota. Since the formation of the moderate Democratic Leadership Council and the election of Bill Clinton, America has led the way in an avowedly centrist approach to progressive politics.

The question of equality in the UK is still hugely important.

When I went to Ed Miliband’s last ever leadership hustings in Haverstock Hill, I mentioned to him that Tony Blair’s autograph called “The Journey” doesn’t even have the word ‘inequality’ in the index. I remember him vividly smiling, and saying, “Oh really?”

One explanation for the rise in inequality under Thatcher, as measured by “the Gini coefficient”, is that the nature of inequality in the UK has changed. A ‘tax and benefit system by lifting incomes at the bottom, and by dragging down incomes at the top. Our top rates of tax remain relatively low by European standards (though certainly high by American ones), which means that redistribution to the poor tends to be paid for ‘by everyone’, not just by the rich.

More of our inequality is instead caused by top incomes ‘racing away’ from everyone else – with incomes at the very top of the distribution growing much faster than those in the middle under Labour. As Peter Mandelson famously said in 1998, “we (Labour) are intensely relaxed about people getting filthy rich.” The dynamics of this inequality are particularly even now, and it is hotly debated as to whether inequality got any worse under Blair or Brown.

In an apparent boost for Osborne, the Treasury said it took £11.5 billion in income tax in April 2013 – a 10 per cent increase on the previous year. There had been fears the lower 45p rate could lead to a loss in revenue for the Government, with Labour branding it a “tax cut for millionaires”. However, Osborne had consistently argued that the 50p tax rate brought in by Gordon Brown in April 2010 did not substantially boost income tax receipts for Treasury coffers. The top rate of income tax had not been in existence for most of the 13 years of the Labour government just gone.

It is also argued that the Liberal Democrat policy of lifting more low and middle-income people out of paying tax altogether is resonating strongly with the general public.

Whatever is happening to the Gini coefficient currently, it has begun to unsettle the Right here in Britain that policies on the left now appear to be currying favour at a populist level:

the public is turning its back on the free market economy and reembracing an atavistic version of socialism which, if implemented, would end in tears. On some economic issues, the public is far more left-wing than the Tories realise or that Labour can believe. If you think I’m exaggerating, consider the findings of a fascinating new opinion poll from YouGov for the Centre for Labour and Social Studies.

The answers to two questions in particular made striking reading: “Do you think the government should have the power to control prices of the following things, or should prices be left to those selling the goods or service to decide?”; and “Do you think the following should be nationalised and run in the public sector, or privatised and run by private companies?”.

The results are terrifying: the UK increasingly believes that it is the state’s job to fix the “right” price, not realising that artificially low prices have always caused shortages and a far greater crisis whenever they have been tried. The great lesson of economics is that bucking markets with artificial price controls always fails; far better to address the root causes of the problem – high prices usually imply scarcity, or monopoly, or generalised inflation – or help those who are suffering directly.

The Liberal Democrats’ catchphrase is ‘a strong economy, and a fair society’.

While Clegg and Cameron appear to be quite chummy, it has been argued that their cultural background of affluence prevents them from understanding social justice and fairness properly.

The leadership, from the same public school roots, appears to have quite a lot in common, but there has been alarm at the schism between the grassroots’ feelings of the Liberal Democrats and Nick Clegg.

As symptomatic of an ‘unfair society’, today, five disabled people won their attempt to overturn the government’s abolition of a £300m fund that helps severely disabled people to “live a full life” in the community. The independent living fund helps 18,500 severely disabled people in Britain to hire a carer or personal assistant to provide round-the-clock care and enable them to work and live independent lives. The government proposed that the ILF be scrapped in 2015, and its resources transferred to local authorities. However, today’s Court of Appeal ruling found that the government had breached its equality duty in failing to properly assess what one of the judges called the “very grave impact” of the closure on disabled people.

The ruling, also at the Court of Appeal, in favour of Cait Reilly was also a two fingers salute at the fair society of Nick Clegg.

And bad luck seems to come in threes. At least.

For a Conservative-Liberal Democrat government which prides itself on ‘equality of opportunity’ for private providers competing with the NHS for taxpayers’ money, the NHS reconfiguration is going incredibly badly.

The Court of Appeal ruled last week that Health Secretary, Mr Jeremy Hunt, did not have power to implement cuts at Lewisham Hospital in south-east London. During the summer, Mr Justice Silber in the High Court had decided also that Mr Hunt acted outside his powers when he decided the emergency and maternity units should be cut back.

And equality keeps on rearing its head in the most unlikely (or likely) places. Take for example NHS resource allocation policy.

The most deprived areas will not lose out under the new formula for allocating funds to clinical commissioning groups, according to NHS England’s finance director Paul Baumann. During a Commons health committee hearing, Baumann revealed that the proposed new formula, to be described in detail in December 2013, will adjust for a health economy’s unmet need, where low life expectancy suggests people are not accessing health services.

It may all just be clever political positioning.

Indeed the Socialist Health Association believes in equality (“Equality”) based on equality of opportunity, affirmative action, and progressive taxation.

But, by reframing the question carefully, Miliband might find that it’s actually the Equality stupid…

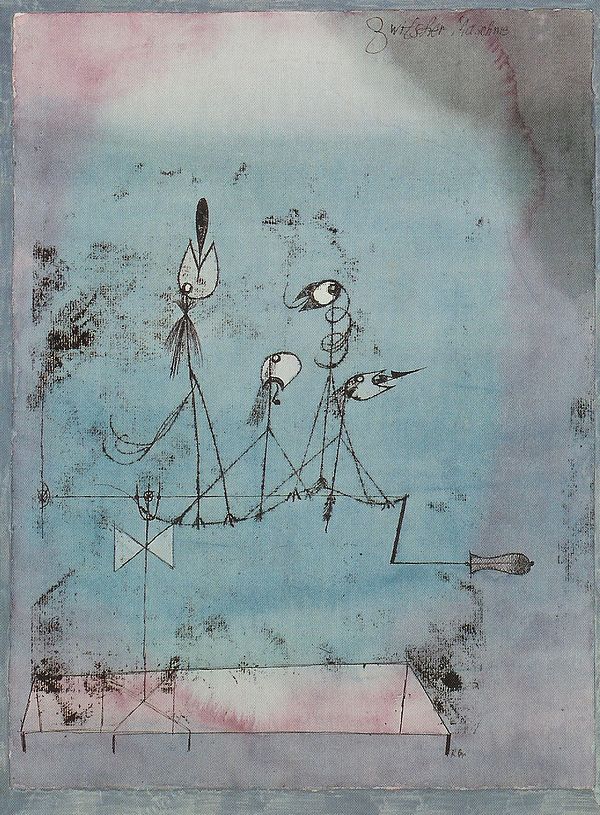

“The twittering machine” – Michael White, the NHS and Paul Klee

Just before I got in a black cab to go to my slot for a viewing of Paul Klee’s amazing paintings at the Tate Modern, I was finishing a Twitter conversation which included Michael White (@MichaelWhite) from the Guardian.

I posted an article on ‘mega dairies‘ on my Facebook. Various approaches to reconfigurations of the NHS had been on my mind. The rôle of the district general hospital had come under scrutiny. Some people think that it might be better to produce “super hospitals”, but my experience from my friends is that they would rather go to a local hospital if they had an acute medical emergency such as acute severe asthma.

This analogy with milk production has no limits for me. I am particularly sick of the ‘we cannot afford the NHS’ argument, although I am very familiar with the ‘funding gap’ arguments from the usual suspects. I think of the ‘more from less’ argument in my analogy as making existing cows produce milk harder. As for the supply of milk? I can buy a carton of milk either from my local corner shop, or I can drive to a huge out-of-town supermarket a few miles away. It’s the same carton of milk.

The moronic economic arguments keep on coming, totally blasting out-of-the-water what the patient or person actually wants. The mantra of ‘no decision about me without me’ has become totally ludicrous when you think that the Lewisham campaign had to take the Secretary of State for Health to court, not only in the High Court but also in the Court of Appeal. If Jeremy Hunt feels the need to appeal the decision at the Court of Appeal in the Supreme Court, I’ll be tempted to emigrate.

I won’t reproduce the entire conversation – but here’s some of it.

You can trace it back to Twitter here.

(Click here to see the thread better.)

And I had an added ‘bonus’ when I turned up at the Tate Modern finally. It dawned on me that, despite the change towards National Socialism that Germany was undergoing for much of Klee’s life, Klee to me looked and sounded like a socialist. I feel socialism is like pornography: you recognise it when you see it. Klee had a close friend called Franz Lotmar, and it turned out that Lotmar introduced Klee to socialism. I was first introduced to socialism by Martin Rathfelder, in contrast. And apparently Oscar Wilde’s “The soul of man under socialism” impressed Klee so much that he gave a detailed summary (and added his thoughts) to another friend called Lily.

The first painting I came to was “The Twittering Machine” (Die Zwitscher-Maschine) – a 1922 watercolour and pen and ink oil transfer on paper. Like other artworks by Klee, it blends biology and machinery, depicting a loosely sketched group of birds on a wire or branch connected to a hand-crank.

Ironically both ‘biology’ (the ageing population) and ‘machinery’ (technology) are being blamed for the demands on the NHS budget in the future, which lead some people to conclude erroneously that the NHS is not sustainable (assuming that you refuse to contemplate methods of funding the NHS properly.) Ed Balls this morning again revisited the narrative of ‘public good, private bad’, advancing as ever Labour’s commitment to “PPPs”, viz public-private partnerships. This of course has been a totemic strand in the NHS policy from both the Conservatives and Labour, examples being the independent sector treatment centres, private finance initiative, and, of course most recently, the Health and Social Care Act (2012). It’s so easy to go with the flow of the associations of the words ‘private’ and ‘public’ that one can loose sight altogether of the actual meanings of the word ‘private’ and ‘public’. For example, thinking about what ‘private’ means, it should be no surprise that private limited companies wish to hide behind the corporate veil in refusing freedom-of-information requests?

In 1941 (the year after Klee died), the celebrated art critic Walter Greenberg called attention to the “privateness” of Klee’s work. It had some reminiscences of a scathing review published in the 1920s in the Dusseldorf Review which likened Klee’s “private work” to “pig Latin” which was ‘unfit for public consumption’. Indeed, walking around the twenty or so rooms of the Klee exhibition, you can really notice the change of style from a ‘completely personal’ style of illustration, more fitting perhaps for the decoration of picture books, to a more public style of display, more fitting perhaps for decoration of whole walls.

One of Klee’s more famous sayings is, “One is always in good company when one has no more money.” Possibly Klee was predicting the political pain of Liam Byrne’s oft-quoted ‘there’s no money left’ note with Labour losing the 2010 general election? However, a narrative in Klee’s art appears to parallel his imputed journey in political philosophy, for example in his attitudes towards ‘collectivism’.

Living with austerity is something which the NHS is trying to do, but it is still very striking how the shift in English health policy is taking place towards value-based outcomes rather than activity per se, mirroring a change in emphasis in US corporate management. Life after the global financial crash in 2o08, not unilaterally caused by Gordon Brown, has also seen a change in emphasis from output as measured by GDP to wellbeing. The concept of a ‘happy peasant’, a peasant who is extremely poor but more contented than an investment banker with a high income, has emerged in recent years in the wellbeing research. Klee’s exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York had as its canvas the Wall Street Crash of October 1929. In the spring of 1930 Klee commented, “What do I prefer? international renown, without a penny; or the well-being of a wealthy local painter?’

Klee once remarked that, instead of taking part in the discussions between competing schools of the Bauhaus, he would sit back and watch both sets of academics fight it out between them. It is tempting for English health policy commentators to sit back and watch the political philosophies of socialism and neoliberalism fight it out for the soul of the NHS.

Unfortunately, this is a fight which there doesn’t seem resolution for in the near future. Even with Andy Burnham’s promise of the ‘NHS preferred provider’, there’s still a market, and there’s still a need for regulation. Possibly Burnham can get rid of the competitive elements with a final thrust towards ‘whole person care’. However, ‘whole person care’ may be a polite way of saying the ‘integrated share model’, and, with prime contractor models lasting at least ten years, Burnham and Miliband’s Labour might find this all remarkably difficult to unwind.

Paul Klee escaped to Switzerland from National Socialism.

Where Labour flees to from section 75 and associated regulations is anyone’s guess. Nonetheless, Burnham and Labour have been emphatic about repealing the Health and Social Care Act (2012).

It’s the necessary start, nonetheless.

“The EY Exhibition: Paul Klee – making visible” runs at the Tate Modern, near Blackfriars, London SE1 between 16 October 2013 and 9 March 2014. For further details, please go here.

Reconfigurations and reconsultations: when is a consultation on the NHS actually legally “fair”?

What this article is not about

Last week, the “Save Lewisham A & E” (@SaveLewishamAE) campaign finally arrived at Court 76 of the Royal Courts of London in the Strand. I should like to give an overview of some of the background issues of this area of law, known as “public law”. To read an account of it, you might like to refer to this brief article on the BBC website.

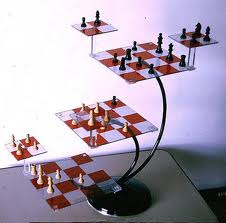

Reconfiguration in the NHS: a need to revisit LeGrand’s chess pieces?

All of this which is the NHS is doing seems to be like one giant 3D game of chess where it is difficult to see all of the pieces. The imposition of the market on the NHS, and the game of chess, is of course a topic more than familiar to Prof Julian LeGrand.

Legrand’s seminal article can be viewed here.

The policy background

Reconfiguration is in fact a highly significant issue in social policy. For example, in a very thought-provoking article entitled, “Publics and markets: What’s wrong with Neoliberalism?”, Clive Barnett from the Faculty of Social Sciences at the Open University writes that:

“Thinking seriously about the political rationalities of liberal governmentality should lead to the recognition of how assumptions about motivation and agency help shape public policy and institutional design. For example, market-reforms in social policy in the UK have been partly driven by fiscal pressures dictated by ‘neoliberal’ macroeconomic policies. However, just as important “was a fundamental shift in policy-makers’ perceptions concerning motivation and agency” (LeGrand 2006). LeGrand suggests a stylized (sic) distinction between two models of motivation and two models of agency.

- If it assumed that people are wholly motivated by self-interest, they are thought of as knaves; if they are thought of as motivated by public-spirited altruism, they are knights.

- If it assumed that people have little or no capacity for independent action, then they are thought of as pawns; if they are treated as active agents, they are thought of as queens.

This distinction helps to throw light upon how institutional reconfigurations of welfare are shaped by changing assumptions about how state agencies function, how officials are motivated, how far people are agents, and in particular how agential capacities of recipients can be mobilised to make public officials more knight-like. LeGrand characterizes the post-1979 period of social policy in the UK as ‘the triumph of the knaves’. It involved two related shifts: towards an empirical assumption about the knavish tendencies of professionals working in public administration; and towards a normative assumption that users should be treated more like queens than pawns. The preference for ‘market’ reforms follows from these two assumptions: “if it is believed that workers are primarily knaves and that consumers ought to be king”, then it follows that “the market is the way in which the pursuit of self- interest by providers can be corralled to serve the interests of consumers” (ibid. 9).”

This suggests that the distinction between Keynsian social democracy and neoliberalism is simply a difference between abstract, substantive principles: egalitarianism (and the state as a vehicle of social justice), versus liberty (and the state as a threat to this). Just as significant is a practical difference between two sets of beliefs about motivation and agency (ibid, 12). ‘Neoliberals’ tend to think of motivation in terms of self-interest and egoism, ‘social democrats’ in terms of knights and altruism. And ‘neoliberals’ tend to presume a capacity for autonomous action, whereas ‘social democrats’ presume this capacity is conditioned and therefore can be justifiably cultivated by state action.

The Handbook of Social Geography, edited by Susan Smith, Sallie Marston, Rachel Pain, and John Paul Jones III. London and New York: Sage

Only time will tell whether this approach is fundamentally flawed.

The English law

Where does any legitimate expectation arise from and do they exist in English law?

Consultation with those likely to be affected by a decision increases the transparency of the process. By allowing engagement in the decision-making process, it may lessen the blow for those affected by the decision that is ultimately taken. Legitimate expectations are very important in the English law. Prior to Coughlan, it was unclear “whether substantive legitimate expectations were recognised within UK law”. In order to understand the issues surrounding legitimate expectations, it is useful to consider the actual details of “Coughlan”, R v. North and East Devon Health Authority ex parte Coughlan (2001) QB 213. The claimant, Miss Coughlan, was a quadriplegic who lived in a hospital for the chronically disabled from 1971-1993 called Newcourt hospital. Newcourt hospital was deemed to be unacceptable for modern care and as a result, she was moved to a new, purpose built facility in 1993 called Mardon House that was specifically designed to accommodate severely disabled patients. Miss Coughlan and other residents in the new facility were given an explicit “promise that they could live there ‘for as long as they chose’ whereby it would be their “home for life”. The evaluation in Coughlan primarily hinged upon the Health authority’s promise in providing a ‘home for life’ to the claimant.

Woolf MR stated (at paragraph 57):

“Where the Court considers that a lawful promise or practice has induced a legitimate expectation of a benefit which is substantive, not simply procedural, authority now establishes that here too the Court will in a proper case decide whether to frustrate the expectation is so unfair that to take a new and different course will amount to an abuse of power. Here, once the legitimacy of the expectation is established, the Court will have the task of weighing the requirements of fairness against any overriding interest relied upon for the change of policy.”

And what about the actual law? R v. Inland Revenue Commissioners ex parte MFK Underwriting Agents Limited (1991) WLR 1545 in which Bingham LJ and Judge J stated that, for a statement to give rise to a legitimate expectation, it must be:

“clear, unambiguous and devoid of relevant qualification” (para. 1570)

The promise has to be made by the decision maker: R (on the application of Bloggs) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2003] EWCA Civ 686, [2003] 1 WLR 2724. Further the promise must be made by someone with actual, or ostensible, authority, otherwise the decision will be ultra vires: South Buckinghamshire DC v Flanaghan [2002] EWCA Civ 690, [2002] 1 WLR 2601. Where a promise is contained in a policy of general application it is not necessary for the applicant to show that he knew of the policy provided he fell within the policy’s general scope, R v Secretary of State for the Home Department ex parte Zeqiri [2002] UKHL 3. Detrimental reliance by the applicant is not an essential prerequisite but it may affect the weight that is to be given to the legitimate expectation.

Is there a need for a consultation at all?

Whether or not there is in law an obligation to consult, where consultation is embarked upon it must be carried out fairly. What is ‘fair’ will obviously depend on the circumstances of the case and the nature of the proposals under consideration: see R (Edwards) v Environment Agency [2006] EWCA Civ 877 per Auld LJ at [90]. This rather open-ended doctrine of fairness means that different judges could reach different views on the lawfulness of the consultation process on the same facts. This raises the possibility that the underlying merits of the decision in question could (even sub-consciously) influence the outcome of any challenge. the decision-maker will usually have a broad discretion as to how a consultation exercise should be carried out (see R (Greenpeace) v. Secretary of State for Trade & Industry [2007] EWHC 311 (Admin) at [62] per Sullivan J); and what should be consulted upon (see The Vale of Glamorgan v. The Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice [2011] EWHC 1532 (Admin) at [25]).

How should the consultation take place?

The decision-maker’s discretion cannot unbounded, however, as it is commonly accepted that certain fundamental propositions must be adhered to. These propositions are known as the Gunning (or Sedley) principles, having been propounded by Mr. Stephen Sedley QC and adopted by Mr. Justice Hodgson in R v. Brent London Borough Council, ex parte Gunning (1985) 84 LGR 168 at 169. They were subsequently approved by Simon Brown LJ in R v. Devon County Council, ex parte Baker [1995] 1 All.E.R. 73 at 91g-j; and by the Court of Appeal in R v. North and East Devon Health Authority, ex parte Coughlan [2001] QB 213 at [108].

The Gunning principles are that:

- the consultation must take place when the proposal is still at a formative stage;

- sufficient reasons must be put forward for the proposal to allow for intelligent consideration and response;

- adequate time must be given for consideration and response; and

- the product of consultation must be conscientiously taken into account.

The English law provides that the actual responses of consultation must be conscientiously considered. This ties in with the first Gunning principle which is really a proxy for whether the decision-maker has made up its mind. If the decision-maker does not properly consider the material produced by the consultation, then it can be accused of having made up its mind; or of failing to take into account a relevant consideration.

Where there are large numbers of individuals who are affected, it may be appropriate to consult with their representatives (e.g. trade unions, or professional bodies). In British Medical Association v. Secretary of State for Health [2008] EWHC 599 (Admin), for instance, a case concerning changes to doctors’ pensions, Mitting J. held that it was sufficient to discharge the consultation obligation for the Minister to have engaged in correspondence with doctors’ leaders. The Court did not say that there needed to be consultation with individual doctors themselves.

Is there ever a need for a re-consultation?

A decision-maker is faced with a conundrum where it has genuinely considered consultation responses and wants to adjust its original proposals, or where circumstances have changed since consultation began. Is the decision-maker required to consult again? This precise issue was discussed by Silber J. in R (on the application of Smith) v East Kent Hospital NHS Trust and another [2002] EWHC 2640 (Admin), [2002] EWHC 2640. Silber J. observed that ‘trivial changes do not require further consideration’ (at [43]). The learned judge was mindful of ‘the dangers and consequence of too readily requiring re-consultation’, noting that in R v. Shropshire Health Authority and Secretary of State ex parte Duffus [1990] 1 Med L R 119, Schiemann J (with whom Lloyd LJ agreed) had stated that:

‘Each consultation process if it produces any changes has the potential to give rise to an expectation in others, that they will be consulted about any changes. If the courts are to be too liberal in the use of their power of judicial review to compel consultation on any change, there is a danger that the process will prevent any change — either in the sense that the authority will be disinclined to make any change because of the repeated consultation process which this might engender, or in the sense that no decision gets taken because consultation never comes to an end. One must not forget there are those with legitimate expectations that decisions will be taken’.

Silber J. concluded that fresh consultation was only required where there was ‘a fundamental difference between the proposals consulted on and those which the consulting party subsequently wishes to adopt’. What then is ‘fundamental’? In R (Elphinstone) v Westminster City Council, [2008] EWHC 1287 (Admin) at [62], Kenneth Parker QC observed that ‘a fundamental change is a change of such a kind that it would be conspicuously unfair for the decision-maker to proceed without having given consultees a further opportunity to make representations about the proposal as so changed.’

Where the Court finds that the consultation process was unfair (or non-existent) it will be in rare cases that the decision-maker will be able to persuade a Court that consultation would have made ‘no difference’. In most cases, a failure to consult fairly will result in the quashing of the underlying decision. In Shoesmith v. Secretary of State for Education [2011] EWCA Civ 852, the Court of Appeal expressed great reluctance to give weight to the ‘no difference’ principle in a case where one might have thought that the decision would inevitably have been the same whatever opportunity to make representations had been provided to the claimant.

In considering the fairness of the consultation, Silber J. held that the council had to comply with the ‘Sedley principles’, and also with the observations of Lord Mustill in R v. Secretary of State, ex parte Doody [1994] 1 AC 531, 550 that ‘Since the person affected cannot make worthwhile representations without knowing what factors may weigh against his interests fairness will very often require that he is informed of the gist of the case which he has to answer’3.

Silber J. held, with respect to the second of the Sedley formulation that:

“It is important that any consultee should be aware of the basis on which a proposal put forward for the basis of consultation has been considered and will thereafter be considered by the decision-maker as otherwise the consultee would be unable to give, in Lord Woolf’s words in Coughlan, either “intelligent consideration” to the proposals or to make an “intelligent response” to it. This requirement means that the person consulted was entitled to be informed or had to be made aware of what criterion would be adopted by the decisionmaker and what factors would be considered decisive or of substantial importance by the decision-maker in making his decision at the end of the consultation process.

I do not think that a consultee would not have been properly consulted if he ought reasonably to have known the criterion, which the decision-maker would adopt or the factors, which would be considered decisive by the decision-maker but that the only reason why the consultee did not know these matters was because, for example, he had turned a blind eye to something of which he ought reasonably to have been aware. Thus, consultation will only be regarded as unfair if the consultee either did not know the criterion to be adopted by the decision-maker or ought not reasonably to have known of this criterion. Of course, what a consultee ought reasonably to have known about the factors, which will be considered decisive by the decision-maker depends on all the relevant circumstances, which may well be different in each case.” [46] – [47]

Conclusion

On the last day of the Lewisham hearing in the High Court, the following was announced, as mentioned on the “Save Lewisham Hospital Campaign: legal challenge” webpage:

“A dramatic back-drop was NHS London’s announcement – strangely coinciding with the final day of our challenge – that they intend to close 9 A&Es from London’s 29 current A&Es over the next 5-6 years.”

The problem about reconfiguration is the “domino effect”, and for all the talk about autonomous units in the NHS, it is clear that this policy is volatile, unstable, and clearly a challenge for people in the community as well as the judiciary. The Lewisham Campaign could just be the tip of the iceberg, as leading QCs and their staff continue to deliberate over whether existant policies imposed by Statute and by the Department of Health are clear and unambigious enough, and whether the Secretary of State is entitled to feel that he has met any tests he has set himself about consultations. From the case law, it will seem that the validity of any consultation will depend on the extent to which the respondents knew about the ambit of the consultation, and it seems that the Court is very keen to hear from those affected by decisions which are made in their name.