Home » Posts tagged 'memory'

Tag Archives: memory

Dementia is not just about losing your memory

“Dementia Friends” is an initiative from the Alzheimer’s Society and Public Health England. In this series of blogpost, I take an independent look at each of the five core messages of “Dementia Friends” and I try to explain why they are extremely important for raising public awareness of the dementias.

Dementia is a general term for a number of progressive diseases affecting over 800,000 people living in the UK, it is estimated.

The heart pumps blood around the circulation.

The liver is involved in making things and breaking down things in metabolism.

The functions of the brain are wide ranging.

There are about 100 billion nerve cells called neurones in the brain. Some of the connections between them indeed do nothing. It has been a conundrum of modern neuroscience to work out why so much intense connectivity is devoted to the brain in humans, compared to other animals.

For example, there’s a part of the brain involved in vision, near the back of the head, known as the ‘occipital cortex’. Horace Barlow, now Professor Emeritus in physiology at the University of Cambridge, who indeed supervised Prof Colin Blakemore, Professor Emeritus in physiology at the University of Oxford, in fact asked the very question which exemplifies one of the major problems with understanding our brain.

That is, why does the brain devote so many neurones in the occipital cortex to vision, when the functions such as colour and movement tracking are indeed in the eye of a fly.

The answer Barlow felt, and subsequently agreed to by many eminent people around the world, is that the brain is somehow involved in solving “the binding problem”. For example, when we perceive a bumble bee in front of us, we can somehow combine the colour, movement and shape (for example) of a moving bumble bee, together with it buzzing.

The brain combines these separate attributes into one giant perception, known as ‘gestalt’.

What an individual with dementia notices differently to before, on account of his or her dementia, will depend on the part of the brain which is affected. Indeed, cognitive neurologists are able to identify which part of the brain is likely to be affected from this constellation of symptoms, in much the same way cardiologists can identify the precise defect in the heart from hearing a murmur with a stethoscope.

In a dementia known as ‘posterior cortical atrophy’, the part of the brain involved with higher order visual processing can be affected, leading to real problems in perception. For example, that’s why the well known author has trouble in recognising coins from their shape from touching them in his pocket. This phenomenon is known as ‘agnosia’, meaning literally ‘lack of knowing’.

If a part of the brain which is deeply involved in personality and behaviour, it would not be a big surprise if that function is affected in a dementia which selectively goes for that part of the brain at first. That’s indeed what I showed and published in an international journal in 1999, for behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia, one of the young onset dementias.

If the circuits involved in encoding a new memory or learning, or retrieving short term memories are affected, a person living with dementia might have problems with these functions. That’s indeed what happens in the most common type of dementia in the world, the dementia of the Alzheimer Type. This arises in a part of the brain near the ear.

If the part of the brain in a dementia which is implicated in ‘semantic knowledge’, e.g. knowledge for categories such as animals or plants, you might get a semantic dementia. This also arises from a part of the brain near the ear, but slightly lower and slightly more laterally.

So it would therefore be a major mistake to think a person you encounter, with memory problems, must definitely be living with dementia.

And on top of this memory problems can be caused by ageing. It would be wrong to pathologise normal ageing in this way.

Severe memory problems can be caused by depression, particularly in the elderly.

In summary, dementia is not just about losing your memory.

Meet Norman and Terry: two people living with a dementia in different ways

“Dementia is not just about sitting in a bathroom all day, staring at the walls.”

So speaks Norman McNamara in his recent BBC Devon interview this week.

This may seem like a silly thing to say, but the perception of some of “people living with dementia” can be engulfed with huge assumptions and immense negativity.

The concept of ‘living well with dementia’ has therefore threatened some people’s framing of a person who happens to have one of the hundred or so diagnoses with dementia.

It’s possible memory might not be massively involved for someone who has been diagnosed with a dementia.

Or as “Dementia Friends” put it, “Dementia is not just about memory loss.”

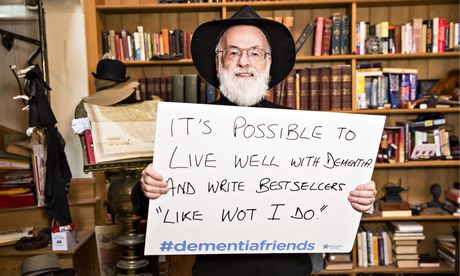

Norman McNamara and Sir Terry Pratchett are people who are testament to this.

“If you made a mistake, would you laugh it off to yourself and say ‘Ha, ha, maybe it’s because I have dementia.””

If somebody else made a mistake, would you laugh at that person and say ‘Ha, ha, maybe it’s because you have dementia.” Definitely not.

There are about a hundred different underlying causes of dementia.

“Dementia” is as helpful a word as “cancer”, embracing a number of different conditions tending to affect different people of different ages, with some similarities in each condition which part of the brain tend to be affected.

These parts of the brain, tending to be affected, means it can be predicted what a person with a medical type of dementia might experience at some stage.

This can be helpful in that the emergence of such symptoms don’t come as much of a shock to the people living with them.

Elaine, his wife, noticed Norman was doing “weird and wonderful things”.

Norman says “my spatial awareness was awful”, and “I was stumbling and falling”.

Norman, furthermore, was putting “red hot tea in the fridge”, and “shower gel, instead of toothpaste, in [my] mouth”.

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a type of dementia that shares symptoms with both Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. It may account for around 10 per cent of all cases of dementia. It is not a rare condition.

It is thought to affect an estimated 1.3 million individuals and their families in the United States.

Problems in recognising 3-D objects, “agnosia”, can happen.

Lewy bodies, named after the doctor who first identified them, are tiny deposits of protein in nerve cells.

See for example this report in this literature.

“Night terrors” have long been recognised in diffuse lewy Body disease.

“The hallucinations are terrific”

The core features tend to be fluctuating levels of ability to think successfully, with pronounced variations in attention and alertness and recurrent complex visual hallucinations, typically well formed and detailed.

See for example this account.

For Norman, it was ‘prevalent in his family’.

Other than age, there are few risk factors (medical, lifestyle or environmental) which are known to increase a person’s chances of developing DLB.

Most people who develop DLB have no clear family history of the disease. A few families do seem to have genetic mutations which are linked to inherited Lewy body disease, but these mutations are very rare.

The patterns of blood flow can help to confirm an underlying diagnosis (see this helpful review).

Also, in this particular ‘type of dementia’, it can be helpful for medical physicians to avoid certain medications (which people with this condition can do very badly with). So therefore while personhood is important here an understanding of medicine is also helpful in avoiding doing harm to a person living with dementia.

However, Norman has been tirelessly campaigning: he, for example, describes how hundreds of businesses in the Torbay-area of Devon have signed up for ‘dementia awareness.”

And, as Norman says, “When you’ve met one person with dementia, you’ve met one person with dementia.”

Sir Terry Pratchett is another person living with dementia.

Sir Terry Pratchett described on Tuesday 13th May 2014 the following phenomenon bhe had noticed:

“That nagging voice in their head willing them to understand the difference between a 5p piece and £1 and yet their brain refusing to help them. Or they might lose patience with friends or family, struggling to follow conversations.”

“Astereognosis” is a feature of ‘posterior cortical atrophy’ (“PCA”).

A good review on the condition of PCA is here.

Sir Terry Pratchett has written a personal reflection on society’s response to dementia and his own experience of Alzheimer’s to launch a new blog for Alzheimer’s Research UK: http://www.dementiablog.org

Sir Terry became a patron of Alzheimer’s Research UK in 2008, shortly after announcing his diagnosis with posterior cortical atrophy, a rare variant of Alzheimer’s disease affecting vision.

He went on to make a personal donation of $1 million to the charity, and has subsequently campaigned for greater research funding, including delivering a major petition to No.10 and countless media appearances.

In his inaugural post for the blog, Sir Terry Pratchett writes: “There isn’t one kind of dementia. There aren’t a dozen kinds. There are hundreds of thousands. Each person who lives with one of these diseases will be affected in uniquely destructive ways. I, for one, am the only person suffering from Terry Pratchett’s posterior cortical atrophy which, for some unknown reason, still leaves me able to write – with the help of my computer and friend – bestselling novels.”

Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) refers to gradual and progressive degeneration of the outer layer of the brain (the cortex) in the part of the brain located in the back of the head (posterior).

The symptoms of PCA can vary from one person to the next and can change as the condition progresses. The most common symptoms are consistent with damage to the posterior cortex of the brain, an area responsible for processing visual information.

Consistent with this neurological damage are slowly developing difficulties with visual tasks such as reading a line of text, judging distances, and distinguishing between moving objects and stationary objects.

Other issues might be an inability to perceive more than one object at a time, disorientation, and difficulty maneuvering, identifying, and using tools or common objects.

Some persons experience difficulty performing mathematical calculations or spelling, and many people with PCA experience anxiety, possibly because they know something is wrong. In the early stages of PCA, most people do not have markedly reduced memory, but memory can be affected in later stages.

Astereognosis (or tactile agnosia if only one hand is affected) is the inability to identify an object by active touch of the hands without other sensory input.

An individual with astereognosis is unable to identify objects by handling them, despite intact sensation. With the absence of vision (i.e. eyes closed), an individual with astereognosis is unable to identify what is placed in their hand. As opposed to agnosia, when the object is observed visually, one should be able to successfully identify the object.

Living well with dementia means different things to different people.

Pratchett further writes:

“For me, living with posterior cortical atrophy began when I noticed the precision of my touch-typing getting progressively worse and my spelling starting to slip. For an author, what could be worse? And so I sought help, and will always be the loud and proud type to speak my mind and admit I’m having trouble. But there are many people with dementia too worried about failing with simple tasks in public to even step out of the house. I believe this is because simple displays of kindness often elude the best of us in these manic modern days of ours.”

As we better understand what dementia is, our response as a society can be more sophisticated. I’ve found one of the most potent factors for encouraging stigma and discrimination is in fact total ignorance.

Both Norman and Terry demonstrate wonderfully: it’s not what a person cannot do, it’s what they CAN DO, that counts.

This is ‘degree level’ “Dementia Friends” stuff, but I hope you found it interesting.

‘Reasons to be cheerful’ part 4. Prof Sube Banerjee’s inaugural lecture in Brighton on living well with dementia.

For me the talk was like a badly needed holiday. I joked with Kay there, a colleague of Lisa, that it felt like a (happy) wedding reception.

@charbhardy hello Chars – not at all the same without you. Thinking of you and G. Very windy on seafront here at Brighton x

— shibley (@legalaware) February 27, 2014

Unknown to me, the title of Prof Banerjee’s talk is an allusion to this famous track from 1979 (when I was five). It’s “Reasons to be cheerful (part 3)” by Ian Drury and the Blockheads.

The Inaugural Lecture – Professor Sube Banerjee (“Professor of Dementia”), ‘Dementia: Reasons to be cheerful’ was held on 26 February, 2014, 6:30 pm – 8:30 pm, at Chowen Lecture Theatre, Brighton and Sussex Medical School, Sussex Campus. BN1 9PX. Details are here on the BSMS website.

I found Prof Banerjee to be a very engaging, ‘natural’ speaker.

I arrived with hours to spare, like how the late Baroness Thatcher was alleged to have done in turning up for funerals.

Brighton are very lucky to have him.

But his lecture was stellar – very humble, yet given with huge gravitas. Banerjee is one of the best lecturers of any academic rank in dementia I have ever seen in person.

Banerjee started off with a suitable ‘icebreaker’ joke – but the audience wasn’t at all nervous, as they all immediately warmed to him very much.

He is ‘quite a catch’. He is able to explain the complicated issues about English dementia policy in a way that is both accurate and engaging. Also, I have every confidence in his ability to attract further research funding for his various teaching and clinical initiatives in dementia for the future.

Most of all, I was particularly pleased as the narrative which he gave of English dementia policy, with regards to wellbeing, was not only accurate, but also achievable yet ambitious.

1979 was of course a big year.

Prof Banerjee felt there were in fact many ‘reasons to be cheerful’, since Ian Drury’s remarkable track of 1979 (above), apparently issued on 20 July of that year.

Banerjee argued that the 1970s which had only given fruit to 209 papers, but things had improved ever since then.

It was the year of course Margaret Thatcher came to power on behalf of the Conservative Party.

In contrast, there have already been thousands of papers in the 2000s so far.

Banerjee also argued that “what we know is more likely to be true” which is possibly also true. However, I immediately reminisced of the famous paper in Science in 1982, “The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction”. This paper, many feel, lay the groundwork for the development of cholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil (“Aricept”, fewer than twenty years later.

It is definitely true that ‘we are better at delineating the different forms of dementia’.

I prefer to talk of the value of people with dementia, but Banerjee presented the usual patter about the economic costs of dementia. Such stats almost invariably make it onto formal grant applications to do with dementia, to set the scene of this particular societal challenge.

I am of course a strong believer in this as my own PhD was in a new way to diagnose the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. In this dementia, affecting mainly people in their 50s at onset, the behavioural and personality change noticed by friends and carers is quite marked. This is in contrast to a relative lack of memory of problems.

Not all dementias present with memory problems, and not all memory problems have a dementia as a root cause. I do happen to believe that this is still a major faultline in English dementia policy, which has repercussions of course for campaigns about ‘dementia awareness’.

A major drive in the national campaigns for England is targeted at destigmating persons with dementia, so that they are not subject to discrimination or prejudice.

The dementia friendship programmes have been particularly successful, and Banerjee correctly explained the global nature of the history of this initiative drive (from its “befriending” routes in Japan). Banerjee also gave an excellent example to do with language of dementia friendship in the elderly, which I had completely missed.

Raising awareness of memory problems in dementia is though phenomenally important, as Alzheimer’s disease is currently thought to be the most prevalent form of dementia worldwide.

The prevalence of dementia may even have been falling in England in the last few decades to the success prevention of cardiovascular disease in primary care.

The interesting epidemiological question is whether this should have happened anyway. Anyway, it is certainly good news for the vascular dementias potentially.

That dementia is more than simply a global public health matter is self-evident.

I’m extremely happy Banerjee made reference to a document WHO/Alzheimers Disease International have given me permission to quote in my own book.

Banerjee presented a slide on the phenomenally successful public awareness campaign about memory.

Nonetheless, Banerjee did speak later passionately about the development of the Croydon memory services model for improving quality of life for persons with mild to moderate dementia.

In developing his narrative about ‘living well with dementia’, Banerjee acknowledged at the outset that the person is what matters at dementia. He specifically said it’s about what a person can do rather than what he cannot do, which is in keeping to my entire philosophy about living well with dementia.

And how do we know if what we’re doing is of any help? Banerjee has been instrumental in producing, with his research teams, acceptable and validated methods for measuring quality of life in dementia.

The DEMQOL work has been extremely helpful here, and I’m happy Banerjee made a point of signposting this interesting area of ongoing practice-oriented research work.

Banerjee of course did refer to “the usual suspects” – i.e. things you would have expected him to have spoken about, such as the National Dementia Strategy (2009) which he was instrumental in designing at the time: this strategy was called “Living well with dementia”.

“I’m showing you this slide BECAUSE I want YOU to realise it IS complicated”, mused Banerjee at the objectives of the current English dementia policy.

I asked Banerjee what he felt the appropriate ‘ingredients’ of the new strategy for dementia might be – how he would reconcile the balance between ‘cure’ and ‘care’ – “and of course, the answer is both”, he said to me wryly.

Banerjee acknowledged, which I was massively pleased about, the current ‘barriers to care’ in this jurisdiction (including the known issues about the “timely diagnosis of dementia”.

Clearly the provision at the acute end of dementia care is going to have to come under greater scrutiny.

I increasingly have felt distinctly underwhelmed by the “medical model”, and in particular the repercussions of this medicalisation of dementia as to how grassroots supporters attempt to raise monies for dementia.

That certain antidepressants can have a lack of effect in dementia – Banerjee’s work – worries me.

That antipsychotics can have a dangerous and destructive effect for persons with dementia – also Banerjee’s work – also clearly worries me.

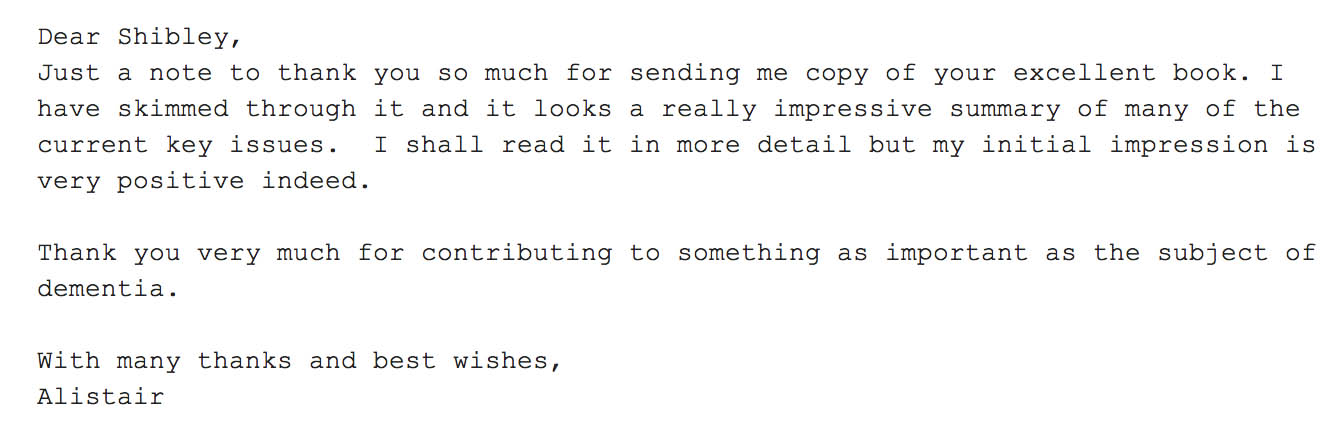

I am of course very proud that Prof Alistair Burns is currently reading my book focused on the interaction between the person and the environment in dementia.

And of course I’m ecstatic that Lisa Rodrigues and Prof Sube Banerjee signed my book : a real honour for me.

I signed Lisa’s book which was most likely not as exciting for her! X

Tour de force #ProfSubeBanerjee inaugural lecture made extra special by presence of @legalaware #reasonstobecheerful pic.twitter.com/qRpWReZOt0

— Lisa Rodrigues (@LisaSaysThis) February 26, 2014

There was a great atmosphere afterwards: the little chocolate brownies were outstanding!

Being an antisocial bastard, I didn’t mingle.

BUT I had a brilliant chat with Lucy Jane Marsters (@lucyjmarsters) who gave me a little bag of ‘Dementia is my business’ badges, very thoughtfully.

We both spoke about Charmaine Hardy. Charmaine was missed (and was at home, devoted to G.)

I’ve always felt that Charmaine is a top member of our community.

@legalaware oh Shibley how did you enjoy it? I wish I could have been there but it’s not possible to leave G anymore. Good being by the sea.

— Charmaine Hardy (@charbhardy) February 27, 2014

This apparently is a ‘Delphinium’.

A reason not to be cheerful was leaving Brighton, for many personal reasons for me.

Not even the Shard was a ‘reason to be cheerful’, particularly.

@legalaware @lucyjmarsters Come back soon, missing you already!!!

— Lisa Rodrigues (@LisaSaysThis) February 27, 2014

But when I came back, I found out that ‘Living well with dementia’ is to be a core part of the new English dementia policy.

Good to see ‘Living well with dementia’ will be a core part of England’s new dementia strategy 14-19 http://t.co/4rknTTzvl9 @nursingtimesed

— Living Well Dementia (@dementia_2014) February 27, 2014

I have, of course, just published a whole book about it.

The photograph of the poppy was of course taken by Charmaine Hardy: I have such great feedback on that one poppy in particular!

And what does the future hold?

Over to Prof Banerjee…

A new way of diagnosing the earliest stages of Alzheimer's Disease?

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia in the UK, characterized by profound memory problems in affected individuals. Currently there is no single test or cure for dementia, a condition that affects over 800,000 people in the UK. The prospect of disease modification has intensified the need to diagnose very early Alzheimer’s Disease with high accuracy. The ultimate goal is possibly to identify and treat asymptomatic individuals with early stages of Alzheimer’s Disease, or those at high risk of developing the disease. By definition, such individuals will be asymptomatic, and disease biomarkers or high-risk traits will be require identification. For pre-symptomatic treatment trials, demonstration of disease modification will ultimately require evidence of delay to symptom-onset or conversion to Alzheimer’s Disease.

In a paper reported recently, UK experts say they may have found a way to check for Alzheimer’s years before symptoms appear. A lumbar puncture test (a test to get spinal fluid from an individual via his back) combined with a brain scan can identify patients with early tell-tale signs of dementia, they believe. Ultimately, doctors could use this to select patients to try out drugs that may slow or halt the disease. Although there are many candidate drugs and vaccines in the pipeline, it is hard for doctors to test how well these work because dementia is usually diagnosed only once the disease is moreadvanced. Researchers at the Institute of Neurology, University College of London, working with the National Hospital for Neurosurgery and Neurosurgery, Queen Square, London, believe they can now detect the most common form of dementia – Alzheimer’s disease – at its earliest stage, many years before symptoms appear.

Their approach checks for two things – shrinkage of the brain and lower than normal levels of a protein, called amyloid, in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that bathes the brain and spinal cord. Experts already know that in Alzheimer’s there is loss of brain volume and an unusual build up of amyloid in the brain, meaning on the whole less amyloid in the CSF. There is, however, rather conflicting evidence for a relationship between measures of amyloid burden and brain volume in healthy controls, The research team reasoned that looking for these changes might offer a way of detecting the condition long before than is currently possible. To confirm this, they recruited 105 healthy volunteers to underwent a series of checks. All subjects were drawn from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), a multi-centre publicly/privately-funded longitudinal study investigating adult subjects with Alzheimer’s Disease, ‘mild cognitive impairment’ of the memory variety, and normal cognition. Participants undergo baseline and periodic clinical and neuropsychometric assessments and serial MRI.

The volunteers had lumbar puncture tests to check their spinal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for levels of amyloid and MRI brain scans to calculate brain shrinkage. The results, published in Annals of Neurology (reference provided below), revealed that the brains of those normal individuals with low CSF levels of amyloid (38% of the group), shrank twice as quickly as the other group. They were also five times more likely to possess the APOE4 cholesterol risk gene and had higher levels of another culprit Alzheimer’s protein, tau. Crucially, the results may allow doctors to pursue avenues to test which drugs might be beneficial in delaying or preventing dementia.

Potential limitations of the study include the relatively high percentage of amyloid-positive normal controls, which may or may not reflect the true population prevalence of individuals with significant amyloid pathology in this age range. There are also a number of issues relating to the reproducibility, reliability, and reporting of biomarker levels in spinal fluid, which need to be standardized to allow for cross-study comparisons.

Notwithstanding that, the scope for further research is enormous. Whether excess rates of brain atrophy in apparently cognitively normal aged patients with CSF profiles suggestive of AD inevitably lead to cognitive impairment, and if so over what time frame, needs to be established. If this proves to be the case, the results we present have significant implications for very early intervention, demonstrating that biomarkers may be used not only to identify Alzheimer’s Disease pathology in asymptomatic individuals, but also to demonstrate and quantify pr-esymptomatic clinical dementia. This suggests that disease-modifying trials in asymptomatic individuals with the aim of preventing progression to cognitive impairment and dementia may be feasible one day.

Reference:

Increased brain atrophy rates in cognitively normal older adults with low cerebrospinal fluid A?1-42. Jonathan M. Schott MD, Jonathan W. Bartlett PhD, Nick C. Fox MD, Josephine Barnes, for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Investigators Article first published online: 22 DEC 2010 DOI: 10.1002/ana.22315

You can view this paper here.

(c) Dr Shibley Rahman 2010

A new twist in the amyloid story in Alzheimer's disease

Tracking the history of where research in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has been difficult leads you naturally to the ‘amyloid story’. Many people now believe that an alteration in brain levels of amyloid ?-proteins (A?) plays a major pathogenic role in AD, a devastating neurodegenerative disorder that causes progressive cognitive impairment and memory loss. AD is characterized by abnormal accumulation of A? in the brain, which leads to the formation of protein aggregates that are toxic to neurons. A? peptides are generated when a large protein called amyloid precursor protein (APP) is cut up into smaller pieces. However, it remains a reasonably consistent observation that the earliest symptoms in AD are early memory deficits. Why, if the build-up of amyloid is widespread, is it the memory that is most remarkable?

Recently, there was a fascinating paper from new research which helped to shed light on the events that underlie the “spread” of AD throughout the brain. The research, published by Neuron [Cell Press] in a recent issue of the journal Neuron, follows disease progression from a vulnerable brain region that is affected early in the disease to interconnected brain regions that are affected in later stages. Important for society in the future is that these findings may contribute to design of therapeutic interventions as targeting the brain region where AD originates would be simpler than targeting multiple brain areas.

The entorhinal cortex (EC) is one of the earliest affected, most vulnerable brain regions in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which is associated with amyloid-? (A?) accumulation in many brain areas. Communication between the EC and the hippocampus is critical for memory and disruption of this circuit may play a role in memory impairment in the beginning stages of AD. Neuroscientists in recent years have felt that it is the entorhinal cortex (and the perirhinal cortex of the parahippocampal cortex) that may contribute to the memory deficits of humans more than possibly the hippocampus itself.

It had not been not clear how EC dysfunction contributes to cognitive decline in AD or whether early vulnerability of the EC initiates the spread of dysfunction through interconnected neural networks. The authors of this study produced transgenic mice with spatially restricted overexpression of mutant APP primarily in neurons of the EC. Selective overexpression of mutant amyloid precursor protein (APP) predominantly in layer II/III neurons of the EC caused cognitive and behavioral abnormalities characteristic of mouse models with widespread neuronal APP over-expression, including hyperactivity, disinhibition, and spatial learning and memory deficits. Importantly, these abnormalities are similar to those observed in mouse models of AD with mutant APP expression throughout the brain.

The researchers also observed abnormalities in the hippocampus, including dysfunction of synapses and A? deposits in part of the hippocampus that receive input from the EC.

The authors concluded that this directly supports the hypothesis that AD-related dysfunction is propagated through networks of neurons, with the EC as an important hub region of early vulnerability.

This work is still entirely consistent with the exciting prospect of immunizing against amyloid in human brains one day in early Alzheimer’s disease (and the mouse models), improving function. Watch this space!

References

H. Braak and E. Braak. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. [Review.] Acta neuropathol

Volume 82, Number 4 [1991] 239-259, DOI: 10.1007/BF00308809

Julie A. Harris, Nino Devidze, Laure Verret, Kaitlyn Ho, Brian Halabisky, Myo T. Thwin, Daniel Kim, Patricia Hamto, Iris Lo, Gui-Qiu Yu, Jorge J. Palop, Eliezer Masliah, Lennart Mucke. Transsynaptic Progression of Amyloid-?-Induced Neuronal Dysfunction within the Entorhinal-Hippocampal Network. Neuron, 2010; 68 (3): 428-441