Home » Posts tagged 'Living well with dementia'

Tag Archives: Living well with dementia

Culture and diversity in living well with dementia

This is a very important chapter to me.

Culture and diversity considerations are hugely pervasive in all of English dementia policy: from the point of timely diagnosis and throughout the course of post diagnostic support.

These are the academic journal references I wish to include in my chapter for my book ‘Living better with dementia: champions for enhanced friendly communities”.

Please do let me know of any initiatives, projects, published papers or reports that you should like me to include in this chapter.

What is listed below is only a start. It does include blogposts, which I intend to include too.

This chapter is of course hugely relevant to global dementia policy.

Aminzadeh F, Byszewski A, Molnar FJ, Eisner M. Emotional impact of dementia diagnosis: exploring persons with dementia and caregivers’ perspectives. Aging Ment Health. 2007 May;11(3):281-90.

Botsford J, Clarke CL, Gibb CE. Dementia and relationships: experiences of partners in minority ethnic communities. J Adv Nurs. 2012 Oct;68(10):2207-17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365 2648.2011.05905.x. Epub 2011 Dec 11.

Bowes A, Wilkinson H. ‘We didn’t know it would get that bad': South Asian experiences of dementia and the service response. Health Soc Care Community. 2003 Sep;11(5):387-96.

Burns A, Mittelman M, Cole C, Morris J, Winter J, Page S, Brodaty H. Transcultural influences in dementia care: observations from a psychosocial intervention study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;30(5):417-23. doi: 10.1159/000314860. Epub 2010 Nov 12.

Chan WC, Ng C, Mok CC, Wong FL, Pang SL, Chiu HF. Lived experience of caregivers of persons with dementia in Hong Kong: a qualitative study. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2010 Dec;20(4):163-8.

Connell CM, Gibson GD. Racial, ethnic, and cultural differences in dementia caregiving: review and analysis. Gerontologist. 1997 Jun;37(3):355-64.

Day A, Francisco A. Social and emotional wellbeing in Indigenous Australians: identifying promising interventions. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2013 Aug;37(4):350-5. doi: 10.1111/1753 6405.12083.

Friedman MR, Stall R, Silvestre AJ, Mustanski B, Shoptaw S, Surkan PJ, Rinaldo CR, Plankey MW. Stuck in the middle: longitudinal HIV-related health disparities among men who have sex with men and women. J Acquire Immune Defic Syndr. 2014 Jun 1;66(2):213-20. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000143.

Johl N, Patterson T, Pearson L. What do we know about the attitudes, experiences and needs of Black and minority ethnic carers of people with dementia in the United Kingdom? A systematic review of empirical research findings. Dementia (London). 2014 May 22. pii: 1471301214534424. [Epub ahead of print]

Khan F, Tadros G. Complexity in cognitive assessment of elderly British minority ethnic groups: Cultural perspective. Dementia (London). 2013 Feb 21;13(4):467-482. [Epub ahead of print]

Kirk LJ Hick R, Laraway A. Assessing dementia in people with learning disabilities: the relationship between two screening measures. J Intellect Disabil. 2006 Dec;10(4):357-64.

La Fontaine J, Ahuja J, Bradbury NM, Phillips S, Oyebode JR. Understanding dementia amongst people in minority ethnic and cultural groups. J Adv Nurs. 2007 Dec;60(6):605-14.

Lim YY, Pietrzak RH, Snyder PJ, Darby D, Maruff P. Preliminary data on the effect of culture on the assessment of Alzheimer’s disease-related verbal memory impairment with the International Shopping List Test. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2012 Mar;27(2):136-47. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acr102. Epub 2011 Dec 23.

Llewellyn, P. The needs of people with learning disabilities who develop dementia: A literature review. Dementia 2011 10: 235-247.

Low LF, Anstey KJ, Lackersteen SM, Camit M, Harrison F, Draper B, Brodaty H. Recognition, attitudes and causal beliefs regarding dementia in Italian, Greek and Chinese Australians. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;30(6):499-508. doi: 10.1159/000321667. Epub 2011 Jan 20.

Manthorpe J, Moriarty J. Examining day centre provision for older people in the UK using the Equality Act 2010: findings of a scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. 2014 Jul;22(4):352-60. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12065. Epub 2013 Aug 17.

McCleary L, Persaud M, Hum S, Pimlott NJ, Cohen CA, Koehn S, Leung KK, Dalziel WB, Kozak J, Emerson VF, Silvius JL, Garcia L, Drummond N. Pathways to dementia diagnosis among South Asian Canadians. Dementia (London). 2013 Nov;12(6):769-89. doi: 10.1177/1471301212444806. Epub 2012 Apr 26.

Morhardt D, Pereyra M, Iris M. Seeking a diagnosis for memory problems: the experiences of caregivers and families in 5 limited English proficiency communities. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010 Jul-Sep;24 Suppl:S42-8. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f14ad5.

Nakanishi M, Nakashima T. Features of the Japanese national dementia strategy in comparison with international dementia policies: How should a national dementia policy interact with the public health- and social-care systems? Alzheimers Dement. 2014 Jul;10(4):468-76.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.06.005. Epub 2013 Aug 15.

Price E. Coming out to care: gay and lesbian carers’ experiences of dementia services. Health Soc Care Community. 2010 Mar;18(2):160-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00884.x. Epub 2009 Aug 25.

Prince M, Acosta D, Chiu H, Scazufca M, Varghese M; 10/66 Dementia Research Group. Dementia diagnosis in developing countries: a cross-cultural validation study. Lancet. 2003 Mar 15;361(9361):909-17.

Regan JL. Ethnic minority, young onset, rare dementia type, depression: A case study of a Muslim male accessing UK dementia health and social care services. Dementia (London). 2014 May 22. pii: 1471301214534423. [Epub ahead of print]

Rovner BW Casten RJ, Harris LF. Cultural diversity and views on Alzheimer disease in older African Americans. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013 Apr-Jun;27(2):133-7. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182654794.

Stokes LA, Combes H, Stokes G. Understanding the dementia diagnosis: the impact on the caregiving experience. Dementia (London). 2014 Jan;13(1):59-78. doi: 10.1177/1471301212447157. Epub 2012 Aug 3.

Sun F, Ong R, Burnette D. The influence of ethnicity and culture on dementia caregiving: a review of empirical studies on Chinese Americans. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2012 Feb;27(1):13-22. doi: 10.1177/1533317512438224.

Werner P, Karnieli-Miller O, Eidelman S. Current knowledge and future directions about the disclosure of dementia: a systematic review of the first decade of the 21st century. Alzheimers Dement. 2013 Mar;9(2):e74-88. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.02.006. Epub 2012 Oct 24.

Wilkinson, H, Kerr, D, Cunningham, C. Equipping staff to support people with an intellectual disability and dementia in care home settings Dementia vol 4(3) 387–400

Journal references for my chapter on living well with dementia and urinary incontinence

I am yet to include influential blogposts, such as this one by Beth Britton (@BethyB1886).

But there is the core of my journal references which I intend to cite in my book chapter on living well with dementia and incontinence.

Please do let me know of any work, in whichever one of the media, you should like me to include. Very many thanks.

Abrams P, Blaivas J, Stanton S, Anderson J. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function.Scand J Urol Nephrol 1988;(Suppl 1)14:5–10.

Afram B, Stephan A, Verbeek H, Bleijlevens MH, Suhonen R, Sutcliffe C, Raamat K, Cabrera E, Soto ME, Hallberg IR, Meyer G, Hamers JP; RightTimePlaceCare Consortium. Reasons for institutionalization of people with dementia: informal caregiver reports from 8 European countries. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014 Feb;15(2):108-16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.09.012. Epub 2013 Nov 12.

Allan L, McKeith I, Ballard C, Kenny RA. The prevalence of autonomic symptoms in dementia and their association with physical activity, activities of daily living and quality of life. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22(3):230-7. Epub 2006 Aug 10.

Allen J, Oyebode JR, Allen J (2009) Having a father with young onset dementia: The impact on well-being of young people. Dementia. 8: 455-480.

Berrios G. Urinary incontinence and the psychopathology of the elderly with cognitive failure. Gerontology 1986;32:119–24.

Boustani MA, Sachs GA, Alder CA, Munger S, Schubert CC, Guerriero Austrom M, Hake AM, Unverzagt FW, Farlow M, Matthews BR, Perkins AJ, Beck RA, Callahan CM. Implementing innovative models of dementia care: The Healthy Aging Brain Center. Aging Ment Health. 2011 Jan;15(1):13-22. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.496445.

Brandeis GH, Baumann MM, Hossain M, Morris JN, Resnick NM. The prevalence of potentially remediable urinary incontinence in frail older people: a study using the Minimum Data Set. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997 Feb;45(2):179-84.

Brocklehurst J, Dillane J. Studies of the female bladder in old age II: cystometrograms in 100 incontinent women. Gerontol Clin 1966;8:306–19.

Campbell A, Reinken J, McCosh L. Incontinence in the elderly: prevalence and prognosis. Age Ageing 1985;14:65–70.

Clarkson, P, Abendstern, M, Sutcliffe, C, Hughes, J, Challis, D. (2012) The identification and detection of dementia and its correlates in a social services setting: Impact of a national policy in England Dementia September 2012 vol. 11 no. 5 617-632

Downs M. Embodiment: the implications for living well with dementia. Dementia (London). 2013 May;12(3):368-74. doi: 10.1177/1471301213487465.

Drennan VM, Norrie C, Cole L, Donovan S. Addressing incontinence for people with dementia living at home: a documentary analysis of local English community nursing service continence policies and clinical guidance. J Clin Nurs. 2013 Feb;22(3-4):339-46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365

2702.2012.04125.x. Epub 2012 Jul 13.

Drennan, VM, Cole, L, Iliffe . A taboo within a stigma? a qualitative study of managing incontinence with people with dementia living at home, BMC Geriatrics 2011, 11:75

Drennan, VM, Greenwood, N, Cole, L, Fader, M, Grant, R, Rait, G, Iliffe, S. Conservative interventions for incontinence in people with dementia or cognitive impairment, living at home: a systematic review BMC Geriatrics 2012, 12:77 doi:10.1186/1471-2318-12-77

Ebly EM, Hogan DB, Rockwood K. Living alone with dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999 Nov-Dec;10(6):541-8.

Eggermont L H, Scherder E J. Physical activity and behaviour in dementia: a review of the literature and implications for psychosocial intervention in primary care. Dementia 2006; 5(3): 4 1-428.

Ekelund P, Rundgren A. Urinary incontinence in the elderly with implications for hospital care consumption and social disability. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1987 Apr;6(1):11-8.

Evans D, Lee E. Impact of dementia on marriage: a qualitative systematic review. Dementia (London). 2014 May;13(3):330-49. doi: 10.1177/1471301212473882. Epub 2013 Jan 25.

Flint A, Skelly J. The management of urinary incontinence in dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1994;9:245–6.

Hägglund D. A systematic literature review of incontinence care for persons with dementia: the research evidence. J Clin Nurs. 2010 Feb;19(3-4):303-12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365 2702.2009.02958.x.

Hasegawa J, Kuzuya M, Iguchi A. Urinary incontinence and behavioral symptoms are independent risk factors for recurrent and injurious falls, respectively, among residents in long term care facilities. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010 Jan-Feb;50(1):77-81. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.02.001. Epub 2009 Mar 17.

Hellström L, Ekelund P, Milsom I, Skoog I. The influence of dementia on the prevalence of urinary and faecal incontinence in 85-year-old men and women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1994 Jul-Aug;19(1):11-20.

Hirasawa, Y, Masuda, Y, Kuzuya, M, Kimata, T, Iguchi, A, Uemura, K. End-o life experience of demented elderly patients at home: findings from DEATH project. Psychogeriatrics, Volume 6, Issue 2, pages 60–67, June 2006

Hirsh D, Fainstein C, Musher D. Do condom catheter collecting systems cause urinary tract infection? JAMA 1979;242:340.

Idiaquez J, Roman GC. Autonomic dysfunction in neurodegenerative dementias. J Neurol Sci. 2011 Jun 15;305(1-2):22-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.02.033. Epub 2011 Mar 25. Review.

Iltanen-Tähkävuori, S. Design and dementia: A case of garments designed to prevent undressing. Dementia January 2012 vol. 11 no. 1 49-59

Jirovec M. Urine control in patients with chronic degenerative brain disease. In: Altman H ed. Alzheimer’s disease problems: prospects and perspectives. New York: Plenium Press, 1986.

Jirovec MM, Wells TJ. Urinary incontinence in nursing home residents with dementia: the mobility-cognition paradigm. Appl Nurs Res. 1990 Aug;3(3):112-7.

Kraemer HC, Taylor JL, Tinklenberg JR, Yesavage JA.The stages of Alzheimer’s disease: a reappraisal. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1998 Nov-Dec;9(6):299-308.

Kraijo, H, Brouwer, W, de Leeuw, R, Schrijvers, G.Coping with caring: Profiles of caregiving by informal carers living with a loved one who has dementia. Dementia November 7, 2011 1471301211421261

Leung FW, Schnelle JF. Urinary and fecal incontinence in nursing home residents. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008 Sep;37(3):697-707, x. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2008.06.005. Review

Lussier M, Renaud M, Chiva-Razavi S, Bherer L, Dumoulin C. Are stress and mixed urinary incontinence associated with impaired executive control in community-dwelling older women? J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2013;35(5):445-54. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2013.789483. Epub 2013 May 8.

Måvall, L, Malmberg, B. Day care for persons with dementia. An alternative for whom? Dementia February 2007 vol. 6 no. 1 27-43

Mo F, Choi BC, Li FC, Merrick J. Using Health Utility Index (HUI) for measuring the impact on health-related quality of Life (HRQL) among individuals with chronic diseases. ScientificWorldJournal. 2004 Aug 27;4:746-57.

O’Donnell BF, Drachman DA, Barnes HJ, Peterson KE, Swearer JM, Lew RA. Incontinence and troublesome behaviors predict institutionalization in dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1992 Jan-Mar;5(1):45-52.

Orrell M, Hancock GA, Liyanage KC, Woods B, Challis D, Hoe J. The needs of people with dementia in care homes: the perspectives of users, staff and family caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008 Oct;20(5):941-51. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208007266. Epub 2008 Apr 17.

Ouslander J, Leach G, Staskin D, Abelson S, Blaustein J, Morishita L, Raz S. Prospective evaluation of an assessment strategy for geriatric urinary incontinence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989 Aug;37(8):715-24.

Rabins P, Mace N, Lucas M. The impact of dementia on the family. JAMA 1982;248:333–5.

Rai, J, Parkinson, R. Urinary incontinence in adults/ Surgery Volume 32, Issue 6, p286–291

Resnick, NM: “Urinary incontinence in the elderly.” Medical Grand Rounds 3:281-290, 1984.

Sakakibara R, Uchiyama T, Yamanishi T, Kishi M. Dementia and lower urinary dysfunction: with a reference to anticholinergic use in elderly population. Int J Urol. 2008 Sep;15(9):778-88. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2008.02109.x. Epub 2008 Jul 14.

Skelly J, Flint A. Urinary incontinence associated with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43:286–94.

Tadros G, Ormerod S, Dobson-Smyth P, Gallon M, Doherty D, Carryer A, Oyebode J, Kingston P. The management of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in residential homes: does Tai Chi have any role for people with dementia? Dementia (London). 2013 Mar;12(2):268-79. doi: 10.1177/1471301211422769. Epub 2011 Nov 20. Review.

Teri L, Borson S, Kiyak HA, Yamagishi M. Behavioral disturbance, cognitive dysfunction, and functional skill. Prevalence and relationship in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989 Feb;37(2):109-16.

Tilvis RS, Hakala SM, Valvanne J, Erkinjuntti T. Urinary incontinence as a predictor of death and institutionalization in a general aged population. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1995 Nov Dec;21(3):307-15.

Toot S, Hoe J, Ledgerd R, Burnell K, Devine M, Orrell M. Causes of crises and appropriate interventions: the views of people with dementia, carers and healthcare professionals. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17(3):328-35. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.732037. Epub 2012 Nov 16.

Ward R, Campbell S. Mixing methods to explore appearance in dementia care. Dementia (London). 2013 May;12(3):337-47. doi: 10.1177/1471301213477412. Epub 2013 Feb 26.

Yap P, Tan D. (2006) Urinary incontinence in dementia – a practical approach, Aust Fam Physician, 35(4), pp. 237-41.

Yokoi T, Okamura H. Why do dementia patients become unable to lead a daily life with decreasing cognitive function? Dementia (London). 2013 Sep;12(5):551-68. doi: 10.1177/1471301211435193. Epub 2012 Mar 16.

The chapter on art, music and creativity for my new book on living better with dementia

The following are the journal references for my chapter on art, music and creativity for my book “Living better with dementia: champions for enhanced friendly communities”. Please do let me know if you wish to have any further academic papers cited. And also please do let me know if you wish local initiatives or innovations to be featured in my chapter, and I will do my best to include them if appropriate.

Very many thanks.

Amaducci L, Grassi E, Boller F. Maurice Ravel and right-hemisphere musical creativity: influence of disease on his last musical works? Eur J Neurol. 2002 Jan;9(1):75-82.

Basaglia-Pappas S, Laterza M, Borg C, Richard-Mornas A, Favre E, Thomas-Antérion C. Exploration of verbal and non-verbal semantic knowledge and autobiographical memories starting from popular songs in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013 May;25(5):785-95. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212002359. Epub 2013 Feb 7.

Beard, R.L. Art therapies and dementia care: A systematic review 2012 11: 633-656.

Bisiani L, Angus J. Doll therapy: a therapeutic means to meet past attachment needs and diminish behaviours of concern in a person living with dementia–a case study approach. Dementia (London). 2013 Jul;12(4):447-62. doi: 10.1177/1471301211431362. Epub 2012 Feb 15.

Blood AJ, Zatorre RJ. Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 Sep 25;98(20):11818-23.

Budrys V, Skullerud K, Petroska D, Lengveniene J, Kaubrys G. Dementia and art: neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease and dissolution of artistic creativity. Eur Neurol. 2007;57(3):137-44. Epub 2007 Jan 10.

Camic PM, Chatterjee HJ. Museums and art galleries as partners for public health interventions. Perspect Public Health. 2013 Jan;133(1):66-71. doi: 10.1177/1757913912468523.

Camic PM, Tischler V, Pearman CH. Viewing and making art together: a multi-session art gallery-based intervention for people with dementia and their carers. Aging Ment Health. 2014 Mar;18(2):161-8. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.818101. Epub 2013 Jul 22.

Camic PM, Williams CM, Meeten F. Does a ‘Singing Together Group’ improve the quality of life of people with a dementia and their carers? A pilot evaluation study. Dementia (London). 2013 Mar;12(2):157-76. doi: 10.1177/1471301211422761. Epub 2011 Oct 31.

Chakravarty A. De novo development of artistic creativity in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2011 Oct;14(4):291-4. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.91953.

Crutch SJ, Isaacs R, Rossor MN. Some workmen can blame their tools: artistic change in an individual with Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2001 Jun 30;357(9274):2129-33.

Eekelaar, C., Camic, P. M., Springham, N. Art galleries, episodic memory and verbal fluency in dementia: An exploratory study. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, Vol 6(3), Aug 2012, 262-272.

Fletcher PD, Clark CN, Warren JD. Music, reward and frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2014 Oct;137(Pt 10):e300. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu145. Epub 2014 Jun 11.

Fletcher PD, Downey LE, Witoonpanich P, Warren JD. The brain basis of musicophilia: evidence from frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Front Psychol. 2013 Jun 21;4:347. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00347. eCollection 2013.

Fornazzari LR. Preserved painting creativity in an artist with Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2005 Jun;12(6):419-24.

Gjengedal E, Lykkeslet E, Sørbø JI, Sæther WH. ‘Brightness in dark places': theatre as an arena for communicating life with dementia. Dementia (London). 2014 Sep;13(5):598-612. doi: 10.1177/1471301213480157. Epub 2013 Mar 13.

Gold K. But does it do any good? Measuring the impact of music therapy on people with advanced dementia: (Innovative practice). Dementia (London). 2014 Mar 1;13(2):258-64. doi: 10.1177/1471301213494512. Epub 2013 Jul 26.

Gordon N. Unexpected development of artistic talents. Postgrad Med J. 2005 Dec;81(962):753-5.

Gross SM, Danilova D, Vandehey MA, Diekhoff GM. Creativity and dementia: Does artistic activity affect well-being beyond the art class? Dementia (London). 2013 May 22. [Epub ahead of print]

Guétin S, Portet F, Picot MC, Pommié C, Messaoudi M, Djabelkir L, Olsen AL, Cano MM, Lecourt E, Touchon J. Effect of music therapy on anxiety and depression in patients with Alzheimer’s type dementia: randomised, controlled study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;28(1):36-46. doi: 10.1159/000229024. Epub 2009 Jul 23.

Hafford-Letchfield T. Funny things happen at the Grange: introducing comedy activities in day services to older people with dementia–innovative practice. Dementia (London). 2013 Nov;12(6):840-52. doi: 10.1177/1471301212454357. Epub 2012 Jul 9.

Holland AC, Kensinger EA. Emotion and autobiographical memory. Phys Life Rev. 2010 Mar;7(1):88-131. doi: 10.1016/j.plrev.2010.01.006. Epub 2010 Jan 11. Review.

Hsieh S, Hornberger M, Piguet O, Hodges JR. Neural basis of music knowledge: evidence from the dementias. Brain. 2011 Sep;134(Pt 9):2523-34. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr190. Epub 2011 Aug 21.

James IA, Mackenzie L, Mukaetova-Ladinska E. Doll use in care homes for people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006 Nov;21(11):1093-8.

Janata P. The neural architecture of music-evoked autobiographical memories. Cereb Cortex. 2009 Nov;19(11):2579-94. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp008. Epub 2009 Feb 24.

LaBar KS, Cabeza R. Cognitive neuroscience of emotional memory. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006 Jan;7(1):54-64. Review.

Lazar A, Thompson H, Demiris G. A systematic review of the use of technology for reminiscence therapy. Health Educ Behav. 2014 Oct;41(1 Suppl):51S-61S. doi: 10.1177/1090198114537067.

Mezirow J. (2000) Learning to think like an adult. In J. Mezirow and Associates, Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in process. (pp. 3-33). San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Miller BL, Boone K, Cummings JL, Read SL, Mishkin F. Functional correlates of musical and visual ability in frontotemporal dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000 May;176:458-63.

Miller BL, Cummings J, Mishkin F, Boone K, Prince F, Ponton M, Cotman C. Emergence of artistic talent in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 1998 Oct;51(4):978-82.

Miller, B.L., Yener, G, Akdal, G. (2005) Artistic patterns in dementia, Journal of Neurological Sciences (Turkish), vol. 22(3), pp. 245-249.

Mitchell G, McCormack B, McCance T. Therapeutic use of dolls for people living with dementia: A critical review of the literature. Dementia August 25, 2014 1471301214548522.

Mitchell G, McCormack B, McCance T. Therapeutic use of dolls for people living with dementia: A critical review of the literature. Dementia (London). 2014 Aug 25. pii: 1471301214548522. [Epub ahead of print]

Mitchell G, Templeton M. Ethical considerations of doll therapy for people with dementia. Nurs Ethics. 2014 Sep;21(6):720-30. doi: 10.1177/0969733013518447. Epub 2014 Feb 3.

Omar R, Hailstone JC, Warren JE, Crutch SJ, Warren JD. The cognitive organization of music knowledge: a clinical analysis. Brain. 2010 Apr;133(Pt 4):1200-13. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp345. Epub 2010 Feb 8.

Pezzati R, Molteni V, Bani M, Settanta C, Di Maggio MG, Villa I, Poletti B, Ardito RB. Can Doll therapy preserve or promote attachment in people with cognitive, behavioral, and emotional problems? A pilot study in institutionalized patients with dementia. Front Psychol. 2014 Apr 21;5:342. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00342. eCollection 2014.

Ramachandran, VS, Hirstein, (1999) The science of art: a neurological theory of aesthetic experience. Journal of Consciousness Studies (6), no.6-7, pp.15-51.

Rankin KP, Liu AA, Howard S, Slama H, Hou CE, Shuster K, Miller BL. A case-controlled study of altered visual art production in Alzheimer’s and FTLD. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2007 Mar;20(1):48 61.

Roe B, McCormick S, Lucas T, Gallagher W, Winn A, Elkin S. Coffee, Cake & Culture: Evaluation of an art for health programme for older people in the community. Dementia (London). 2014 Mar 31. [Epub ahead of print]

Salimpoor VN, Benovoy M, Longo G, Cooperstock JR, Zatorre RJ. The rewarding aspects of music listening are related to degree of emotional arousal. PLoS One. 2009 Oct 16;4(10):e7487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007487.

Seeley WW, Matthews BR, Crawford RK, Gorno-Tempini ML, Foti D, Mackenzie IR, Miller BL. Unravelling Boléro: progressive aphasia, transmodal creativity and the right posterior neocortex. Brain. 2008 Jan;131(Pt 1):39-49. Epub 2007 Dec 5.

Stevens, J 2012, ‘Stand up for dementia: performance, improvisation and stand up comedy as therapy for people with dementia; a qualitative study’, Dementia, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 61-73.

Takahata K, Saito F, Muramatsu T, Yamada M, Shirahase J, Tabuchi H, Suhara T, Mimura M, Kato M. Emergence of realism: Enhanced visual artistry and high accuracy of visual numerosity representation after left prefrontal damage. Neuropsychologia. 2014 May;57:38-49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.02.022. Epub 2014 Mar 11.

Takeda M, Hashimoto R, Kudo T, Okochi M, Tagami S, Morihara T, Sadick G, Tanaka T. Laughter and humor as complementary and alternative medicines for dementia patients. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010 Jun 18;10:28. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-28.

Tanaka, Y, Nogawa, H, Tanaka, H. (2012) Music Therapy with Ethnic Music for Dementia Patients, International Journal of Gerontology Volume 6, Issue 4, December 2012, Pages 247 257.

Topo, P, Mäki,O, Saarikalle, K, Clarke, N, Begley, E, Cahill, S, Arenlind, J, Holthe, T, Morbey, H, Hayes, K, Gilliard, J. Dementia October 2004 Assessment of a Music-Based Multimedia Program for People with Dementia vol. 3 no. 3 331-350

Woods RT, Bruce E, Edwards RT, Elvish R, Hoare Z, Hounsome B, Keady J, Moniz-Cook ED, Orgeta V, Orrell M, Rees J, Russell IT. REMCARE: reminiscence groups for people with dementia and their family caregivers – effectiveness and cost-effectiveness pragmatic multicenter randomised trial. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(48):v-xv, 1-116. doi: 10.3310/hta16480.

Zeilig H. Gaps and spaces: representations of dementia in contemporary British poetry. Dementia (London). 2014 Mar 1;13(2):160-75. doi: 10.1177/1471301212456276. Epub 2012 Aug 17.

A personal budget approach blind to the underlying neuroscience of dementia is doomed to failure

One of the critical messages in recent public health awareness campaigns about dementia is that there is much more to a person living with dementia than his or her actual diagnosis. This focus on personhood, how the person living with dementia understands himself or herself, in the context of his past, present and relationships, and in relation to his or her own environment, is of course critical. It is likely to be embraced in the overall approach of whole person care in this jurisdiction.

Much of the current policy in England in dementia is driven by a scant existence of relevant evidence, for example the mental distress and lack of appropriate management caused by false diagnoses of dementia not confirmed elsewhere in the system. For example, even in the eight years since the seminal paper by Gail Mountain in the journal ‘Dementia’ in 2006, we have had little progress in the literature on the extent to which people at various stages of different types of dementia are able to manage, or want to manage, their own conditions, depending on their cognitive, affective or motivational abilities. This blogpost is about the form of personal budgets where people with dementia are given the money directly to spend, without any broker.

Likewise, the approach of personal budgets in dementia has equal scant regard to an approach necessitated by the cognitive neuroscience. Being able to operate a budget is likely to require a good understanding of mathematics; and it has been known for decades, or if not centuries, that people with disruption of the functioning of a part of the brain known as the parietal cortex can have problems with calculations. This is called ‘dyscalculia’.

Some people with dementia might have real problems in anticipating future outcomes (as shown in the famous Anderson paper) or have problems in making accurate cognitive estimates (as discussed in the famous paper by Shallice and Burgess). The people with dementia for whom these problems are likely to surface are those with disruption of the functioning of a part of the brain known as the frontal lobe.

Also, I showed myself in 1999, published in Brain, that people in early stages of behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia can be prone to make risky decisions. Others have argued it is more of a problem with impulsivity.

Nobody has any intention of turning people living with early stages of dementia into amateur accountants, but even with the basic budgets you need to have an ability to deal with income, expenditure, costing and reasonable forecasting.

So there is clearly an evidence base emerging that, despite full legal capacity, there are some persons living with dementia who are best not served by direct payments so that they can pursue their ‘choice’. But the introduction of this has been surreptitious, couched in language such as “empowering people with dementia to take control of their own risk behaviour.”

Such flowery language is best kept in marketing manuals, I feel. At a time when report after report has demonstrated that there is not a strong evidence base for improvement in clinical outcomes (such as falls for people with dementia), we must be able to ask for whose benefit are these self-directed budgets for people with dementia?

There is report after report of ‘widening the market’, complaining about the lack of quality ‘control’ of market offerings for dementia. And yet we simultaneously have a care regulator complaining regularly about the quality of dementia services in trusts in England. We have a poor evidence base on what level of budget is sufficient to allow a choice; clearly someone who has an insufficient budget cannot find a choice argument at all compelling.

And is the quality of market offerings being properly regulated to prevent fraud? The last few years has witnessed a series of seemingly attractive offerings for living well with dementia, some of which are extremely good (such as assistive technology, better design of wards and the home), and some of which are poor. There is insufficient evidence here too that the regulator is able to cope confidently except in the clearest examples of fraud.

There is much good work being done in social care and medicine, but with a drive for shiny, instant products, we must never lose sight of the fact that care from social care has been cut consistently over a long period of time. Whenever someone explains the case for personal budgets, there is almost certainly a concomitant explanation of an exploding care budget. However, it would be wrong to slash frontline care while touting ‘The Big Society’ in the same way it would be completely wrong to cut in real terms per caput allocations of care or to pursue backdoor rationing in the name of choice.

Is the use of GPS “trackers” for people living with dementia necessary and proportionate?

This is the introduction to “Living better with dementia: how champions can challenge the boundaries”, chapter 12, “Do GPS trackers have a rôle to play in living better with dementia?”

“We live in a ‘surveillance society’. If you happen to log in on Facebook, Facebook can identify your location exactly, and then can offer you a choice of cheap hotels there. The idea that a GPS system (“global positioning system”), as a tracker, can identify you where you are might seem like an invasion of privacy, but not much of an invasion of privacy than Facebook, arguably. And indeed a non-invasive system might be better than a method of physical restraint for certain people with dementia. It would be hard to justify a tracking device in a person who is not a candidate for physical restraint though conceivably?

Tracking for people with dementia raises strong emotions, not helped with some of the discussion acting at the extremes, such as a hypothermic person with dementia found in a ditch due to a GPS tracker. But the conflation of ‘tracking’, with ‘tagging’ as per frequent offenders in the criminal law, is an unfortunate one. At a time when there are international drives towards decreasing stigma in people with dementia, people warn about the mission creep that is offered with tracking: for example, one wonders how long it might be for a GPS tracker to become an implantable micro-chip. The word ‘tracking’ itself, however, is a misnomer, in that these trackers do not actively ‘follow’ people, but can pinpoint someone’s location through the method of ‘trilateral’. Satellite detectors happen to be there, in the same way that public telephone boxes happen to be there. Public telephone boxes take on a different atmosphere if highly illegal activity happen to be taking there, and there is a proportionate need to intervene. But intervene in what? Here we are talking about a criminal activity, rather than intervene in a person at risk of causing harm to himself or herself? The question that someone can consent to doing himself or herself avoiding being at personal harm, exercising too his or her own ethical right to autonomy, and a clear definition of consent depends on a clear definition of capacity. A human right to privacy which is inalienable albeit qualified may transcend capacity, causing further disquiet in legal circles. And, besides, people who do happen to travel beyond their physical zone might not be doing so out of any particular malice: a person with dementia may simply have problems with spatial navigation. Presumption of innocence is pivotal in the law is pivotal, and laying blame on innocent people is unacceptable – even subtlely through terms laced with innuendo such as “wandering”.

One wonders whether the legal definition of capacity across a number of jurisdictions, which depends on an “all-or-nothing” construct, can cope with those dementias where cognitive abilities fluctuate or cognitive demands vary. Is legal capacity to make a sandwich the same as capacity to write a paper on human rights? And who is best to make a decision about fitting a GPS tracker? It must surely cause concern if a caregiver would wish to fit one simply because it makes the monitoring of an individual an easier job, rather than the person with dementia wishes to be more independent. It is therefore clear that there is no right answer to GPS systems in dementia, especially as the term “dementia” itself is a portmantaneau term for lots of different clinical conditions, with different types and ‘severities’. Whether GPS trackers are necessary and proportionate for any one person living with dementia is a rather abstract question, given that there are so many different subtypes of dementia making some more prone to travel beyond their locality than others. With GPS tracking in dementia, we see yet another example where ‘one glove fits all’ approach is a dismal failure.”

“Leadership is the art of mobilizing others to want to struggle for shared aspirations.”

“McLaughlin: Leadership has so many definitions that sometimes that term loses its meaning. How do you define it?

Kouzes: Leadership is the art of mobilizing others to want to struggle for shared aspirations. That part about struggling for shared aspirations may set our definition apart.”

I’ve also been though the motions of detailed study of leadership styles in my own MBA.

But this definition of James Kouzes really struck a chord with me.

This is of course not a particularly impressive ‘leadership style’, one sedentary guy with an iPad mini with a large product placement in shot?

I have fleetingly thought too about who is the exact target audience of my book.

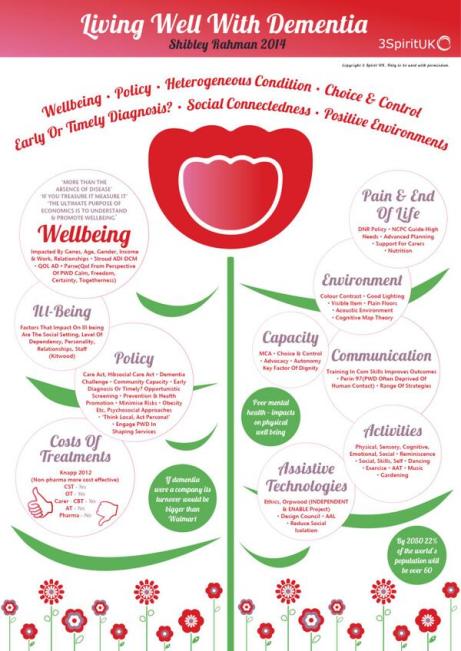

While ‘Living well with dementia’ is not a ‘self help book’, it is a fact that many people living well with dementia have warmly received the book.

In fact, in the front row in my line of vision to the left, two people sat, a son and his mother with dementia.

It turns out the son found my talk ‘inspiring’, and thanked me, in front of his mother, for saying which he perceived as powerful: that it’s more important to concentrate on what people can do in the present, rather than they cannot do.

And what did I conclude was the driving intention of an international policy plank about living well with dementia?

I concluded that a positive wellbeing is about a person being content with himself or herself, and his or her own environment.

This is not an issue of being drugged up with a ‘cure for dementia’. It is though saying something equally positive about dementia, if not more positive.

I do not consider the Alzheimer’s Show an “event with a buzz”. For me, it was like a wedding of a best friend. I was thrilled to meet Chris, Jayne, Suzy, Rachel, Louise, Natasha, Joyce, Nigel, Tracey, Tony, and Tommy, some for the first time.

And what you see is what you get with them.

Chris concluded, “Living better with dementia would’ve been a better title.”

And Tommy agreed.

Chris and Tommy live well with dementia.

I agreed too. In a nutshell, ‘living well with dementia’ runs the danger of imposing your moral judgment or ‘standards’ on what living well with dementia is.

For me, living well in alcoholic recovery means not downing a bottle of neat gin when I get up, like I used to do in late 2006/early 2007 when I hit a rock bottom. (The actual rock bottom was when I had a cardiac arrest and epileptic seizure heralding a six week coma in the summer of 2007, rendering me physically disabled.)

But it’s a big thing for me that people who are living well with dementia are actually interested in – and supportive of – my book.

You see, I concede that I don’t live with a dementia yet to my knowledge – though many London cabbies conclude that I do [nicely], when I tell them the title of my book and they see me struggling get into their cab.

Chris pointed out something at first glance very true today – that I didn’t have many friends living with dementia as friends then, when I was writing my book.

Chris is in fact wrong. “Any” not “many”.

Tommy said something curious recently, that it’s ironic that it took an event such as the Alzheimer’s Show in Manchester to bring us all together.

But he’s right. We’re not there for any other reason than to share experiences.

Suzy commented that ‘I get it’. And I do think do, for all sorts of reasons, many of which were quite unintended.

I am currently writing ‘Living better with dementia: champions challenging the boundaries”. It’s going to be a toughie, but I think I can do it.

If only Kate were there too…

“It’s possible to live well with dementia”: a crucial message in @DementiaFriends

“Dementia Friends” is an initiative from the Alzheimer’s Society and Public Health England. In this series of blogpost, I take an independent look at each of the five core messages of “Dementia Friends” and I try to explain why they are extremely important for raising public awareness of the dementias.

This is the plucky group of persons living with dementia at the Alzheimer’s Disease International meeting in Puerto Rico in 2014.

That’s right. They’re not there as representatives of any organisation, but there on their own as individuals as members of the “Dementia Action Alliance”.

They happen to have received a diagnosis of dementia.

So why is this “it’s possible to live well with dementia” even a statement in “Dementia Friends“, a Public Health England initiative delivered by the Alzheimer’s Society. It should be obvious shouldn’t it?

The answer comes in the ‘icebreaker’ exercise at the beginning of the Dementia Friends session. Attendees are asked to think of the first word that springs to mind when they think of dementia.

“Suffering”

“Horrible”

“Terrible”

And indeed it would be wrong to ignore how distressing a diagnosis of dementia can be for certain individuals with dementia. Take for example people with diffuse Lewy Body disease, typically individuals in the younger age bracket in their 50s, who have complete insight into the condition, realise that memory might be going, and are exasperated at the ‘night terrors’.

‘Living well with dementia’, conversely, is supposed to counteract the negative word associations may people have about dementia. It’s felt that such negative connotations contribute to the stigma individuals with dementia can experience after their diagnosis. This can ultimately lead to discrimination, hence the need for communities which are welcoming to such individuals.

It also happens to be the name of the English dementia strategy, which was introduced by the last Government in 2009. Dementia as a policy plank now in England has full cross party support, and the current ‘Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge’ is due to come to an end next March 2015.

In the panel session above, somebody asks whether a dementia diagnosis should ever be withheld from a person with dementia. Kate Swaffer, living with dementia herself, believes firmly ‘no’, saying that one would never dream of withholding a diagnosis of cancer.

Policy in this jurisdiction and others has given due attention to whether the person receiving the diagnosis of dementia actually benefits – put simply is it ‘disabling’ rather than ‘enabling’.

Does it shut more doors than it opens?

But even if one takes the view that dementia is a disability which one is perfectly entitled to do on reading the case law surrounding the Equality Act (2010), the issue of making reasonable adjustments around this particular disability then becomes not a trivial one.

Richard Taylor elegantly advances this argument. Big Pharma have been impressively unimpressive in the offerings for dementia, although some report some substantial short-term symptomatic benefit for symptoms.

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) have stated clearly that such medications do not slow the progression of the condition.

But they did offer very recently some enormously useful guidance on supporting people to live well with dementia.

And this issue is a push-pull one. Given the relative inefficacy of the medical interventions, one is possibly attracted to the things one might do to promote living well with dementia.

In a world of ‘whole person care’, where there might be care coordinators helping to break down the silos of service provision for people living with dementia, we might arrive at a destination where people with dementia do receive some help.

This might include assistive technologies, other innovations, or access to advocacy services.

And for a person who has received a diagnosis of dementia, Richard Taylor argues that trust is pivotal. This is somewhat related to Kate Swaffer’s views that ‘support groups’ (for carers) might inadvertently encourage division.

Whilst members of the support and care network clearly have substantial ‘needs’, not least in behavioural and psychological considerations, promoting quality of life for people living with dementia is clearly going to be a vital policy plank for the future.

Some inroads have already been made, as I recently discussed here, but there is a lot yet further still to do I feel.

Can you live well with dementia and suffer at the same time?

First, read Kate Swaffer’s poem. “Who’s suffering?”

When the media fires bullets of suffering in their magazines (quite literally), it is not clear who is the suffering by, what they’re suffering, how they’re suffering, when they’re suffering, and why they’re suffering.

Many readers suffer at this lack of clarity.

It’s pretty clear this narrative has got extremely distorted for no clear reason. What do the caring professions or the media have to gain by describing so much suffering?

And are people really suffering as purported?

Are there any randomised placebo-controlled drug trials where the relief of “suffering” in #dementia is a reported outcome?

Kate Swaffer (@KateSwaffer)’s poem conversely is a very helpful contribution, based on a personal experience of living well with a dementia.

“Rhetoric referring to Alzheimer’s disease as ‘the never ending funeral’ or ‘a slow unraveling of the self’ implies that diagnosed individuals and their families alike are victims of a dreaded disease.”

So comment Beard and colleagues.

“The fact that the words Alzheimer’s disease conjure up images of a hideous, debilitating condition demonstrates that an Alzheimer’s diagnosis can be both “a stigmatizing label and a sentence”. When depicted as a ‘living death’, Alzheimer’s can have countless social-psychological consequences for those diagnosed. Within a medical model, the relatives of persons with dementia are ascribed the role of ‘caregiver’ with a focus on the associated stressors or ‘burden’. Subsequently, health promotion efforts have historiiccally positioned family members as the ‘second’ or ‘hidden’ victims.”

Of course, this discussion is not confined to Alzheimer’s disease.

It is not uncommon for people who love people living with advanced dementia to have a miserable time, and suffer from that.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of ‘dementia’, a disease of the brain. It’s not just about memory, although memory problems can be a common feature of Alzheimer’s disease early on in particular.

There is more to the person than the dementia. It’s possible to live well with a dementia. And dementia is not necessarily associated with ageing.

But some critics of ‘living well with dementia’ have attacked the concept saying it is trying to airbrush or sanitise suffering. I hope that this is not a widespread belief, as it is not true.

Across a number of jurisdictions, the word ‘sufferer’, like ‘victim’, is avoided in common parlance and academic papers when referring to people getting on with their own lives.

The term ‘live well with dementia’ is not indeed to enforce a degree of pleasantry on the lives of people. Contentment is not compulsory. But the term conveys a notion which is a pure and simple reaction to people being written off on the receipt of a diagnosis of dementia.

We owe much of the current drive in policy to ‘person centred care’ from the seminal work of the late great Prof Tom Kitwood on personhood. Persons living with dementia have been classified as “empty shells”, a label that may contribute to the development of paternalistic attitudes and behaviors toward care.

Kitwood suggested that people with dementia are often depersonalized and actively disempowered.

Research into the “self” in dementia is important for a number of reasons. It is important to understand how people with dementia experience their sense of self because this has implications for how people cope with the illness, how they relate to others, including friends, family, and health professionals, and what any types of intervention might be appropriate for them.

One person, interviewed by Wendy Hulko, described the experience as “hellish”.

But it turned out that this word was chosen partly out of word finding difficulties.

“Well, having um a difficulty coming out with the right words for example or phrases or um having difficulty with uh numbers and um dates, times, um having difficulty coming up with um, difficulty um, coming up with just a common expression uh, or um even words that are very frequently used by anyone without the disease and um having difficulty coming up with just ordinary expressions…”

Several of the participants dismissed the significance of having dementia, some focusing on the lack of impact it had on their lives. Several of the participants tolerated dementia, noting the inconvenience it caused and downplaying the negativity associated with it.

Despite extremely powerful national advocacy organisations founded over a quarter century ago in the United States and the United Kingdom, the voice of people with all forms of dementia has been surprisingly slow to emerge.

A recent exception to this has been the Dementia Alliance International.

The medical model has unintentionally forced a narrative in the media which does present people living with dementia in the positive light. Such ‘ringfencing’ of the person with dementia positions them as withdrawing from social life rather than considering how their social roles may have been withdrawn from them, which demotes them to ‘patient’ or ‘dementia sufferer’.

Such biomedical reductionism, arguably, can, therefore, create additional obstacles for diagnosed individuals and their families.

People with dementia, like all of us, undoubtedly have “rough spots” along an individualistic path of dementia, but the person is more important than the diagnosis as reflected in strategies for circumventing the rough spots.

There are typically personal, interactional, and environmental factors that caused them difficulties. Strategies included concrete activities, emotional responses, and environmental adaptations.

A number of devices can be used cognitive aids, made various modifications, garnered assistance from others’ engagement, akin to how people like me live with physical disability.

And often the language itself is intensely stigmatising.

Take for example this example by Dupuis and colleagues.

Such current language and discussion around “challenging behaviours” have the effect of blaming persons with dementia for behaviors and labeled persons as violent, aggressive, disruptive, challenging and so forth. This was hurtful and stigmatising and did not reflect the meanings of the actions of persons with dementia.

Conversely, it is quite often – and incredibly politically incorrect to say so – a failure by the care or support network to understand communication by a person with dementia amidst intense frustration.

Sarah Lamb notes at the beginning of this year that the current North American “successful ageing” movement offers a particular normative model of how to age well, one tied to specific notions of individualist personhood emphasising independence, productivity, self-maintenance, and the individual self as project.

However, Lamb concludes that the “successful ageing” narrative “might do well to come to better terms with conditions of human transience and decline, so that not all situations of dependence, debility and even mortality in late life will be viewed and experienced as “failures” in living well.”

This thought is bound to raise eyebrows.

An emerging political approach suggest that individuals with dementia are viewed as having transgressed “core cultural values—productivity, autonomy, self-control, cleanliness—and these failures damage the ‘victim’s’ status as an adult, and indeed, full humanity” (Herskovits, 1995: 153).

In articulating a “political” model of dementia, Susan M. Behuniak suggests that one is inviting very different meanings:

“everything from absolute control over the individual to a total lack of public policy, from an emphasis on individual rights to that of social responsibility, and from laws that draw absolute lines to those that accommodate shades of grey.”

Although dementia is not traditionally viewed as a power question but as a medical condition, power in its most traditional of formulations can be seen when debates arise over who should decide matters involving the individual with dementia.

This is, I feel, also an issue when we talk about a ‘carer’ or ‘support’ for a person with dementia. Whilst not as unsubtle as the word ‘sufferer’, there is an implicit power relationship there for me.

Chris Roberts [@mason4233], one of the @DementiaFriends, himself a card-carrying member of the ‘living well with dementia’ club has often remarked as follows:

So it is possible to suffer and live well with dementia.

But once you’ve met one person with dementia, you’ve met only one person with dementia.

But hold on.

Carly Findlay, like Chris and Kate, also puts it beautifully, this time writing from Melbourne about “ichthyosis“.

In her piece, “I get told I suffer… I don’t suffer.”

Ask others for their opinion if possible, or those closest to them.

It’s very important that no views are simply shouted down, particularly since it will be an important strand of the English dementia strategy (probably from next year.)

Further reading

Herskovits, E. (1995). Struggling over subjectivity: Debates about the ‘self

Social stigma, music and living well with dementia

There are 800,000 people living with dementia in the UK, it is thought.

There is no cure at the moment.

“Attitudes are changing. The old stigma is being replaced by the recognition that people with the disease can be helped.”

Later on, John Humphrys spoke this morning to a number of clinicians involved in managing persons with dementia.

The package begins with an initiative called ‘Singing for the brain’.

Singing for the Brain is a service provided by Alzheimer’s Society which uses singing to bring people together in a friendly and stimulating social environment.

The power of music, especially singing, to unlock memories and kickstart the grey matter is an increasingly key feature of dementia care. It seems to reach parts of the damaged brain in ways other forms of communication cannot.

Organisations such as Music for Life, Lost Chord, Golden Oldies and Live Music have also improved accessibility live musicians, both professional and amateur, most of them trained to deal with the special needs of an elderly, memory-impaired audience.

A nice overview of some of these initiatives is given on the Age UK website.

The way in which the brain might do this is indeed interesting.

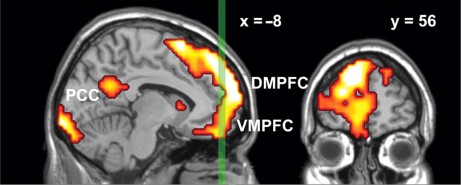

Results from Petra Janata (1999) suggest that the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) associates music and memories when we experience emotionally salient episodic memories that are triggered by familiar songs from our personal past.

MPFC acted in concert with lateral prefrontal and posterior cortices both in terms of tonality tracking and overall responsiveness to familiar and autobiographically salient songs.

The MPFC is right at the front of the brain.

My interpretation using the “bookcase analogy” of “Dementia Friends” is that while the bookcase representing your memories for events is shaking this bookshelf representing memories triggered by music is unaffected.

It’s virtually the same as the bookcase responsible for sporting memories, in my view of things.

I wonder if ability to reactive sporting memories is correlated with ability to reactivate music memories?

This would explain the efficacy of this approach to living well with dementia.

We not only have to face the reality of the scope of people living with dementia in society.

But as Humphrys articulates in his item.

“Part of it is how society is set up to respond to people who look confused… instead of reacting in a fearful way, we are thinking in terms of how to help such people”, so comments Dr Andrew Crombie from South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust.

You can listen to the whole of the presentation by John Humphrys – for one week only from the date of this blogpost – on the BBC iPlayer.

Play from about 1 hr 34 mins in on this page.

Social stigma is the extreme disapproval of (or discontent with) a person or group on socially characteristic grounds that are perceived, and serve to distinguish them, from other members of a society. Stigma may then be affixed to such a person, by the greater society, who differs from their cultural norms.

Social stigma can result from the perception (rightly or wrongly) of mental illness, physical disabilities, diseases such as leprosy (see leprosy stigma), illegitimacy, sexual orientation, gender identity, skin tone, education, nationality, ethnicity, ideology, religion (or lack of religion[3][4]) or criminality. Attributes associated with social stigma often vary depending on the geopolitical and corresponding sociopolitical contexts employed by society, in different parts of the world.

According to Goffman in “Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity”, there are three forms of social stigma:

- Overt or external signs, such as scars

- Deviations in personal traits, including forms of medical conditions

- “Tribal stigmas” are traits, imagined or real, of ethnic group, nationality, or of religion that is deemed to be a deviation from the prevailing normative ethnicity, nationality or religion.

Prof Alistair Burns is the National Clinical Lead for dementia for NHS England, and was interviewed by John Humphrys this morning.

“You have highlighted very well in the discussions today and yesterday .. about something which we hear much more of now, and that is: people can live well with dementia. On the interview yesterday, we heard from Linda who felt she was very supported by her friends yesterday, and you said that when you interviewed Grace she felt normal.”

Humphrys was concerned that this was only representative of people living with dementia in the earliest stages.

Burns said, “There are many things that we can do, whatever the stage of dementia.”

“If we look at person-centred care, that is treating people as individuals we’ve heard from ‘Singing for the brain’ and ‘Life Story Work’ can bring people together.”

And have we been doing this successfully thus far?

“It’s fair to say that there has been pockets of excellent work being done around the country.. And one of the things which we must do is to encourage people to do and to learn from areas which are doing well like the example we saw yesterday, and like the example we saw today.”

Humphrys then went on to probe Burns much more about the stigma.

“We know that, from surveys of people for people above the age of 55, dementia is the most feared disease, much more than, say, stroke, heart disease or cancer.”

“There is something about the stigma. What we have seen is a lessening of the stigma, things like ‘Dementia Friends‘, working with schools, and getting ideas into schools.”

Humphrys proposed that it is necessary was to get rid of the idea that there was something about dementia that is “shaming”.

“What you got yesterday from today and yesterday was that people felt normal and supported. But I hear from my own clinic that, experiences where once people receive a diagnosis of dementia, others cross the street.”

“And trying to wrestle that is important.”