Home » Posts tagged 'judicial review'

Tag Archives: judicial review

Infertility treatment: when poor access-to-medicine to access-to-law come together

It is estimated that infertility affects 1 in 7 heterosexual couples in the UK. Since the original NICE guideline on fertility published in 2004 there has been a small increase in the prevalence of fertility problems, and a greater proportion of people now seeking help for such problems.

In a striking letter published on 18 June 2013 in the BMJ entitled, “NICE promises on infertility and caesarean section are unmet” from Guy’s and St. Thomas’ Hospital, Lawrence Mascarenhas (a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist), Zachary Nash (medical student), and Bassem Nathan (consultant surgeon), describe that NICE ‘promises on infertility and caesarean section are unmet’. Mr Mascharenhas and colleagues argue that “Current underfunding of the NHS means that some National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines are unachievable”. According to Matthew Limb previously, writing in the BMJ, leaders of NHS organisations in England have voiced grave warnings about how the build up of financial pressures is affecting the care of patients (Limb, 2013). Current updated NICE guidelines (CG156) recommend that women under 42 years with unexplained infertility should be offered three cycles of in vitro fertilisation funded by the NHS. Others state that all pregnant women should be able to choose an elective caesarean without obstetric or psychological indications.

The authors of this letter in the BMJ proposed that this,

“results in raised expectations that cannot be met and a flurry of referrals of disappointed women to the private sector.”

The authors specifically report that:

“Our anonymous telephone research involving all London maternity units two months ago showed that commissioners are unwilling to fund caesareans at maternal request. It also showed that women with previous caesareans are being pushed down the road of a trial of vaginal birth because of targets for reducing these operations. This causes great disappointment and anxiety for these women, who are often met with the clinician’s response “operations are more dangerous,”4 which is contrary to NICE guidance.

Furthermore, the postcode lottery for NHS funded in vitro fertilisation is well documented. We believe that these updated NICE guidelines will perpetuate the belief that these guidelines are only implementable for a

select educated few who can successfully argue their case with professionals. Others have called for legal clarity in this respect.”

The area of “judicial review” in civil litigation is the procedure by which the courts examine the decisions of public bodies to ensure that they act lawfully and fairly. On the application of a party with sufficient interest in the case, the court conducts a review of the process by which a public body has reached a decision to assess whether it was validly made. The court’s authority to do this derives from statute, but the principles of judicial review are based on case law which is continually evolving. Judicial review is very much a remedy of last resort. Although the number of judicial review claims has increased in recent years, it can be difficult to bring a successful claim and a court may refuse permission to bring a claim if an alternative remedy has not been exhausted. A claimant should therefore explore all possible alternatives before applying for judicial review.

Judicial review has a number of heads. For example, under the head of “legitimate expectation“, a public body may, by its own statements or conduct, be required to act in a certain way, where there is a legitimate expectation as to the way in which it will act. A legitimate expectation only arises in exceptional cases and there can be no expectation that the public body will act unfairly or beyond its power.

Judicial review, like arguably access to medicine, has been attacked by the current Government. The issue of infertility treatment illustrates, it can be argued, a national disgrace in poor access to both the medicine and the law. In an address to the CBI, David Cameron vowed to cut “time-wasting” caused by the “massive growth industry” in judicial reviews. He apparently wants fewer reviews, specifically for those challenging planning, and he wants to shorten the limitation period for bringing a review. This is all in aid of a new “growth cabinet” – cutting “red tape” and “bureaucratic rubbish” and “trying to speed decision making”.

Martha Gill writing in the New Statesman has argued that,

“At the moment, a judicial review is one of the only ways by which the courts can scrutinise the decisions of public bodies. Legal Aid is available for it – prisoners, for example, can bring judicial reviews against decisions of the parole board. So there are the cons – disempowering people who didn’t have much power in the first place, and increasing opportunities for public bodies to overstep the mark, unchallenged. What of the pros? Cameron argues that the judicial review industry is growing, holding up progress and costing money.”

Because of the “silo effect”, medics will have tended to notice on their watch a decline in universality and comprehensive nature of the NHS, with a focus on section 75 NHS regulations emphasising competitive tendering, but will be largely uncognisant of the battles the legal profession are facing of their own in the annihilation of high street legal aid services and cuts in judicial review. This letter in the BMJ from a leading Consultant’s firm at Guys’ and St.Thomas’ here in London demonstrates what a mess the confluence of these two policies, pretty horrific separately, can lead to.

References

Limb, M. (2013) Current financial pressures are worst ever, say NHS chiefs, BMJ, Jun 3, 346. f3616.

Mascharenas, M., Nash, Z., and Nathan, B. (2013) Letter: NICE promises on infertility and caesarean section are unmet, BMJ, Jun 18, 346.

Time to have a radical rethink of the rôle of the company in UK national life

In 1897, in a remarkable piece of judicial intervention in the economic life of the country, it was considered convenient to permit the company to have its own legal personality [Salomon v. A. Salomon & Co. Ltd [1897] A.C. 22]. The decision of the House of Lords has remained the integrity of the separate personality of the company: the corporate veil will only be lifted in the most extreme of circumstances. The company or corporation, in the U.K., has grown in prominence like it has done in the U.S. Of course, it would be a “cheap shot” simply to rattle off a list of corporate disasters internationally, such as phone hacking or chemical plant explosions. Disasters happen in the public sector too. However, arguably, the unions in England have experienced more than their fair share of criticism, particularly from the Conservatives. Indeed, the donations page on the Conservatives website actually asks for donations to help protect the UK against the unions: “We believe that Labour, along with the Trade Unions who provide 85 per cent of their donations, are standing in the way of improving Education, reforming the Welfare State and reducing the budget deficit. We need your help in standing up to them.” It is no coincidence that deunionised workforces tend to have much lower pay, and less enforceable basic employment rights over redundancy and dismissal. There is no evidence that a more ‘flexible’ workforce would have a significant impact on the profitability of the UK as a whole. ‘Being in it together’ has become a farce with hardly a dent into the profits of leading CEOs in the UK.

And yet the narrative has been one of hostility towards the unions by the Conservatives, and indeed it is significant that none of the anti-Union rhetoric has been appreciably reversed by New Labour. The Conservatives have a big thing about ‘accountability’, yet their major stakeholders have latterly been big corporates who are not elected in the same way that unions are. It is well known that David Cameron’s Tory-led coalition wishes not so much as to ‘reduce the size of the state’, but to have functions of the state outsourced. People did not “vote for” multi-national companies, and yet the Government wishes these companies to take on an increasing workload in the state’s functions. This outsourcing experiment is not cheap. With any organisational change, you have invest much time and money into abolishing structures and forming new ones, but, most significantly, there can be enormous difficulties in cultural change. That is not a reason necessarily, however, why outsourcing should be abandoned.

The main issue about having companies having an increasing rôle in national life, an agenda which neither the Conservatives or the Liberal Democrats were open about prior to the general election of 2010, is: who really runs Britain? The oddity in the argument against trade unions is that, whilst most opponents of trade unions appear to produce loud critical remarks, very few object to a democratic right to a membership of a trade union. Ed Miliband concedes that the company or corporation is part of national life, but his argument is against any section of society having undue influence, in his conceptualisation of ‘responsible capitalism’. In his world, he would prefer corporations to act as good ‘corporate citizens’. However, the production of the company in English law as a separate entity to its shareholders further impedes the democratic process. The case law developed for a reason. The main benefit which flows from the Salomon principle, arguably, is one of efficiency. Whereas previously a business organised as a partnership could only create contracts in a very complicated way – involving each partner becoming a party to that contract – as soon as it is recognised that a company is a distinct, legal person in itself then the company can create contracts in its own name. Consequently, the process of creating contracts with businesses became much simpler. However, the reality, as we approach 2013, is rather different. It is sometimes hard to identify corporate donors of political parties, as corporate donors do not provide donations as themselves. The electoral rules hinge on full disclosure and transparency in the system, but it is perfectly possibly for major shareholders from ‘behind the veil’ to donate to political parties. Therefore, unless you happen to know who the major shareholders are you are unlikely to find much of interest on the Electoral Commission website. Proving a link between donation and subsequent policy will be virtually impossible to establish in all cases, not least because of the temporal relationship, but the “corporate veil” is unlikely to be “pierced” for the rather specific scenario of electoral donations. Revealing ‘conflicts of interest’ is difficult to disentangle from aggressive lawful lobbying, and will not be offensive unless the rules and regulations about proper disclosure and shareholder approval for transactions of a certain nature have been breached.

Traditionally though, the corporate veil is likely to be pierced, in specific scenarios. Piercing the corporate veil or lifting the corporate veil is a legal decision to treat the rights or duties of a corporation as the rights or liabilities of its shareholders. Usually a corporation is treated as a separate legal person, which is solely responsible for the debts it incurs and the sole beneficiary of the credit it is owed. Common law countries usually uphold this principle of separate personhood, but in exceptional situations may “pierce” or “lift” the corporate veil. A simple example would be where a businessman has left his job as a director and has signed a contract to not compete with the company he has just left for a period of time. If he set up a company which competed with his former company, technically it would be the company and not the person competing. Largely through the influence of the great Lord Denning, it is likely a court would say that the new company was just a “sham”, a “fraud” or some other phrase, and would still allow the old company to sue the man for breach of contract. A court would look beyond the “legal fiction” to the reality of the situation. Donating to a political party is not unlawful or illegal, but it is frustrating, when transparency is so pivotal to electoral donations, that many examples of methods of donation exist which can get round the electoral rules:

“Critics of proposals to introduce caps on donations point out that there are various ways in which big donors can evade a cap by splitting up their contributions to political parties. There are grounds to suggest that such practices may already be common. Big donations from specific wealthy individuals sometimes occur alongside equally generous donations made by husbands, wives and other family members. Donations made via corporate entities may also serve to ‘bundle’ donations, or partially obscure their source. For instance, some company directors donate alongside partners at the same business; whilst larger groups of wealthy people have formed unincorporated associations through which to channel political funds.”

There are new ways why the law is being tested in this new outsourcing of public duties landscape. There is an arguable case that private limited companies, performing public functions, should be open to ‘freedom of information’ legislation, particularly if doing such sensitive functions as running prisons or hospitals. Secondly, there is also a feasible case that private limited companies performing public functions, should be open to ‘judicial review’, as for example being involved in NHS procurement. In a way, the Conservatives “started it”. By starting a hate campaign against the Unions, which has seen Margaret Thatcher and successors unite against the workers, there is a case now that there should be a radical rethink of the rôle of the company in UK national life. This is a narrative which could be taken on by the legislature, should they feel ready for the challenge, or, failing this, maybe senior lawyers would like to have a go?

Time to have a radical rethink of the rôle of the company in UK national life

In 1897, in a remarkable piece of judicial intervention in the economic life of the country, it was considered convenient to permit the company to have its own legal personality [Salomon v. A. Salomon & Co. Ltd [1897] A.C. 22]. The decision of the House of Lords has remained the integrity of the separate personality of the company: the corporate veil will only be lifted in the most extreme of circumstances. The company or corporation, in the U.K., has grown in prominence like it has done in the U.S. Of course, it would be a “cheap shot” simply to rattle off a list of corporate disasters internationally, such as phone hacking or chemical plant explosions. Disasters happen in the public sector too. However, arguably, the unions in England have experienced more than their fair share of criticism, particularly from the Conservatives. Indeed, the donations page on the Conservatives website actually asks for donations to help protect the UK against the unions: “We believe that Labour, along with the Trade Unions who provide 85 per cent of their donations, are standing in the way of improving Education, reforming the Welfare State and reducing the budget deficit. We need your help in standing up to them.” It is no coincidence that deunionised workforces tend to have much lower pay, and less enforceable basic employment rights over redundancy and dismissal. There is no evidence that a more ‘flexible’ workforce would have a significant impact on the profitability of the UK as a whole. ‘Being in it together’ has become a farce with hardly a dent into the profits of leading CEOs in the UK.

And yet the narrative has been one of hostility towards the unions by the Conservatives, and indeed it is significant that none of the anti-Union rhetoric has been appreciably reversed by New Labour. The Conservatives have a big thing about ‘accountability’, yet their major stakeholders have latterly been big corporates who are not elected in the same way that unions are. It is well known that David Cameron’s Tory-led coalition wishes not so much as to ‘reduce the size of the state’, but to have functions of the state outsourced. People did not “vote for” multi-national companies, and yet the Government wishes these companies to take on an increasing workload in the state’s functions. This outsourcing experiment is not cheap. With any organisational change, you have invest much time and money into abolishing structures and forming new ones, but, most significantly, there can be enormous difficulties in cultural change. That is not a reason necessarily, however, why outsourcing should be abandoned.

The main issue about having companies having an increasing rôle in national life, an agenda which neither the Conservatives or the Liberal Democrats were open about prior to the general election of 2010, is: who really runs Britain? The oddity in the argument against trade unions is that, whilst most opponents of trade unions appear to produce loud critical remarks, very few object to a democratic right to a membership of a trade union. Ed Miliband concedes that the company or corporation is part of national life, but his argument is against any section of society having undue influence, in his conceptualisation of ‘responsible capitalism’. In his world, he would prefer corporations to act as good ‘corporate citizens’. However, the production of the company in English law as a separate entity to its shareholders further impedes the democratic process. The case law developed for a reason. The main benefit which flows from the Salomon principle, arguably, is one of efficiency. Whereas previously a business organised as a partnership could only create contracts in a very complicated way – involving each partner becoming a party to that contract – as soon as it is recognised that a company is a distinct, legal person in itself then the company can create contracts in its own name. Consequently, the process of creating contracts with businesses became much simpler. However, the reality, as we approach 2013, is rather different. It is sometimes hard to identify corporate donors of political parties, as corporate donors do not provide donations as themselves. The electoral rules hinge on full disclosure and transparency in the system, but it is perfectly possibly for major shareholders from ‘behind the veil’ to donate to political parties. Therefore, unless you happen to know who the major shareholders are you are unlikely to find much of interest on the Electoral Commission website. Proving a link between donation and subsequent policy will be virtually impossible to establish in all cases, not least because of the temporal relationship, but the “corporate veil” is unlikely to be “pierced” for the rather specific scenario of electoral donations. Revealing ‘conflicts of interest’ is difficult to disentangle from aggressive lawful lobbying, and will not be offensive unless the rules and regulations about proper disclosure and shareholder approval for transactions of a certain nature have been breached.

Traditionally though, the corporate veil is likely to be pierced, in specific scenarios. Piercing the corporate veil or lifting the corporate veil is a legal decision to treat the rights or duties of a corporation as the rights or liabilities of its shareholders. Usually a corporation is treated as a separate legal person, which is solely responsible for the debts it incurs and the sole beneficiary of the credit it is owed. Common law countries usually uphold this principle of separate personhood, but in exceptional situations may “pierce” or “lift” the corporate veil. A simple example would be where a businessman has left his job as a director and has signed a contract to not compete with the company he has just left for a period of time. If he set up a company which competed with his former company, technically it would be the company and not the person competing. Largely through the influence of the great Lord Denning, it is likely a court would say that the new company was just a “sham”, a “fraud” or some other phrase, and would still allow the old company to sue the man for breach of contract. A court would look beyond the “legal fiction” to the reality of the situation. Donating to a political party is not unlawful or illegal, but it is frustrating, when transparency is so pivotal to electoral donations, that many examples of methods of donation exist which can get round the electoral rules:

“Critics of proposals to introduce caps on donations point out that there are various ways in which big donors can evade a cap by splitting up their contributions to political parties. There are grounds to suggest that such practices may already be common. Big donations from specific wealthy individuals sometimes occur alongside equally generous donations made by husbands, wives and other family members. Donations made via corporate entities may also serve to ‘bundle’ donations, or partially obscure their source. For instance, some company directors donate alongside partners at the same business; whilst larger groups of wealthy people have formed unincorporated associations through which to channel political funds.”

There are new ways why the law is being tested in this new outsourcing of public duties landscape. There is an arguable case that private limited companies, performing public functions, should be open to ‘freedom of information’ legislation, particularly if doing such sensitive functions as running prisons or hospitals. Secondly, there is also a feasible case that private limited companies performing public functions, should be open to ‘judicial review’, as for example being involved in NHS procurement. In a way, the Conservatives “started it”. By starting a hate campaign against the Unions, which has seen Margaret Thatcher and successors unite against the workers, there is a case now that there should be a radical rethink of the rôle of the company in UK national life. This is a narrative which could be taken on by the legislature, should they feel ready for the challenge, or, failing this, maybe senior lawyers would like to have a go?

Is socialism consistent with judicial review?

The simplest answer to, ‘Is socialism consistent with judicial review?’ might be ‘Yes absolutely – it’s a very useful way to hold authorities to account’.

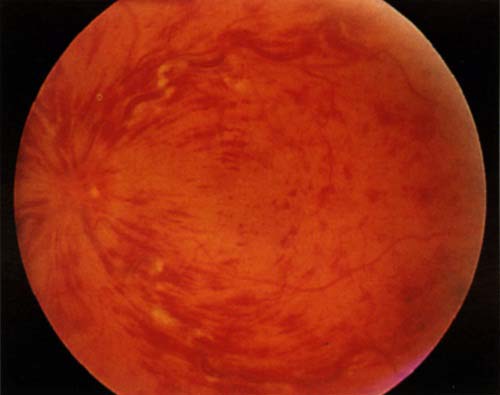

To my knowledge, “central retinal vein occlusion” is still a popular ‘spot diagnosis’ in the clinical examination for the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the UK.

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (“NICE”), as a public body with statutory powers from law, makes decisions about treatments in the NHS, and a number of its decisions have been subject to ‘judicial review’ in the past. Judicial review is a procedure in English law by which the courts in England and Wales can supervise the exercise of public power on the application of an individual. A person who feels that an exercise of such power by a government authority, such as a minister, the local council or a statutory tribunal, is unlawful, perhaps because it has violated his or her rights, may apply to the Administrative Court (a division of the High Court) for judicial review of the decision and have it set aside (quashed) and possibly obtain damages.

NICE concluded in July 2011 that dextramethasone-intravitreal implants implants, that are installed every six months and help prevent sight deterioration, and represented a cost-effective use of NHS resources. The macular is the central part of the retina responsible for colour vision and perception of fine detail. Macular oedema is where fluid collects in the retina at the macular area, which can lead to severe visual impairment. Straight lines may appear wavy, and one may have blurred central vision or sensitivity to light. However, according to a recent article in the Guardian newspaper, a survey of 125 hospital trusts in England with eye health services conducted by the Royal National Institute of Blind People in February found that of the trusts that responded, 45 were providing a full service and 37 were providing either a restricted service or no service. In his article, Sir Michael Rawlins in the Health Services Journal said he had advised the RNIB to make an application to the high court and seek a judicial review.

Socialism and judicial review, however, have not historically been natural ‘soulmates’. In EP Thompson’s “Whigs and Hunters” (1975), it is argued that judicial review (and ‘rule of law’) has been an useful way of exerting influence in capitalist ideologies, particular in the context of ‘abuse of power’. It can be argued that judicial review and ‘the rule of law’ go hand-in-hand in that the ‘rule of law’ fundamentally provides that nobody is above the law, and that the law is supreme. To that extent, everyone has an equal say, and judicial review can therefore represent the needs of underprivileged members of society. To that extent, it might be very reconcilable with socialism; sufferers of dementia might be considered some of the more disadvantaged members of society, and a decision to make cholinesterase inhibitors available for amelioration of cognitive symptoms might be a meritorious one in terms of fairness.

Many criticisms of judicial review have, interestingly, centred around the validity of the process. For example, it can be argued, reasonably effectively, that judges currently in England are not a representative stratum of the population. This is a general issue with the senior members of the legal profession, generally, and is essentially one to do with the politics of the judiciary, as discussed by JAG Griffith (1991). Judges in the High Court are not politically elected, and therefore there are qualms about them entering into questions of public policy; the counter-argument to that is that they are simply examining issues of procedural irregularity, fairness or legitimate expectation, amongst other grounds, of the wishes of parliament, defined originally by parliament. This contention has been most forceful when the politics have been seen as ideologically ‘strong’, such as under Margaret Thatcher. Judges have had a tendency to ignore the social values of society, and indeed many senior judges currently at the Bar in England and Wales emphasise that a robust advantage is conferred by judges not passing moralistic or other judgements based on social mores.

Perhaps the most compelling reason to reject judicial review, for socialists, is if judicial review is seen as a mechanism by capitalist societies to reject socialist values. In theory, any legal mechanism can only be interpreted by the political ideology which underlines it, at one end, but the judiciary and the legislature and executive are entirely separate in structure and function (it is argued, at the other end). However, a way to temper such criticism might be to argue that, even if socialism were not the prevailing ideology, socialism can exert a useful moralistic influence on decision-making which can make a real difference for a minority of patients in the NHS. Anyway, the validity of judicial review is a genuine problem legally, and, while I think instinctively it offers benefits to patients in a socialist NHS, its methodology should not escape from scrutiny altogether. As Prof Mauro Cappelletti indeed says, one page of practical tips is worth many books of abstract theory (or something like that!)

GDL revision sheet on principles of judicial review

You’re likely to consider the general principles of judicial review in England before going to consider in detail one or more of the arms of ‘grounds for judicial review’ such as procedural impropriety or legitimate expectation. You might find this revision sheet (Principles of judicial review) useful, but please be guided by your law school/learning provider for exact details (especially with regard to course materials, cases and texts).

Andy Burnham's letter to David Cameron about BSF (Building Schools for the Future")

Rt Hon David Cameron MP

10 Downing Street

London

SW1A 2AA

14th February 2011

Dear Prime Minister,

High Court ruling on Building Schools for the Future

On Friday, the High Court ruled that the Education Secretary’s decisions on Building Schools for the Future constituted an ‘abuse of power’.

I am sure you will agree that this is an extremely serious charge to be made against a member of your Cabinet.

The Secretary of State’s decisions were found to be ‘unlawful’ in respect of six councils on the Building Schools for the Future programme.

The Judge also ordered that the decisions affecting these councils be reconsidered with “an open mind”.

From his response to the ruling, the councils concerned will find it hard to believe that the Secretary of State’s mind is anything other than firmly made up. At no point has he acknowledged the defectiveness of his original decision-making process. He appears to have pre-judged any review of the decisions by so robustly defending his original actions.

Given that questions also remain over whether he ignored the advice of lawyers and civil servants in pressing ahead without consultation, there are serious doubts over whether the public could have any confidence in a review of the decision by this Secretary of State.

These matters affect the hopes of communities and the life chances of children across the country. To restore the confidence of the six councils in this case that they will receive a fair hearing, I urge you to remove the Secretary of State from any further role in the review process.

Best Wishes

RT HON ANDY BURNHAM MP

Shadow Secretary of State for Education