Home » Posts tagged 'health policy'

Tag Archives: health policy

Dementia – where now?

The most ‘perfect’ scenario for dementia screening would be to identify dementia in a group of individuals who have absolutely no symptoms might have subtle changes on their volumetric MRI scans, or might have weird protein fragments in their cerebrospinal fluid through an invasive lumbar culture; and then come up with a reliable way to stop it in its tracks The cost, practicality and science behind this prohibit this approach.

There are well defined criteria for screening, such as the “Wilson Jungner criteria“. Prof Carol Brayne from the University of Cambridge has warned against the perils of backdoor screening of dementia, and the need for evidence-based policy, publicly in an article in the British Medical Journal:

“As a group of clinical and applied researchers we urge governments, charities, the academic community and others to be more coordinated in order to put the policy cart after the research horse. Dementia screening should neither be recommended nor routinely implemented unless and until there is robust evidence to support it. The UK can play a unique role in providing the evidence base to inform the ageing world in this area, whilst making a positive difference to the lives of individuals and their families in the future.”

However, a problem has arisen in how aggressively to find new cases of dementia in primary care, and a lack of acknowledgement by some that incentivising dementia diagnosis might possibly have an untoward effect of misdiagnosing (and indeed mislabelling) some individuals, who do not have dementia, with dementia. Unfortunately there are market forces at work here, but the primary consideration must be the professional judgment of clinicians.

Diagnosing dementia

There is no single test for dementia.

A diagnosis of dementia can only be confirmed post mortem, but there are ‘tests’ in vivo which can be strongly indicative of a specific dementia diagnosis (such as brain biopsy for Variant Creutzfeld-Jacob disease or cerebral vasculitis), or specific genetic mutations on a blood test (such as for relatively rare forms of the dementia of the Alzheimer type).

Memory vs non-memory functions in CANTAB

CANTABmobile is a new touchscreen test for identifying memory impairment, being described as a ‘rapid memory test’. The hope is that memory deficits might be spotted quickly in persons attending the National Health Service, and this is indeed a worthy cause potentially. In the rush to try to diagnose dementia quickly (and I have explained above the problem with the term “diagnose dementia”), it is easy to conflate dementia and memory problems. However, I demonstrated myself in a paper in Brain in 1999 using one of the CANTAB tests that patients with behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) were selectively impaired on tests sensitive to prefrontal lobe function involving cognitive flexibility and decision-making. I demonstrated further in a paper in the European Journal of Neuroscience in 2003 that such bvFTD patients were unimpaired on the CANTAB paired associates learning test.

bvFTD is significant as it is a prevalent form of dementia in individuals below the age of 60. The description given by Prof John Hodges in the current Oxford Textbook of Medicine chapter on dementia is here. Indeed, this chapter cites my Brain paper:

“Patients present with insidiously progressive changes in personality and behaviour that refl ect the early locus of pathology in orbital and medial parts of the frontal lobes. There is often impaired judgement, an indifference to domestic and professional responsibilities, and a lack of initiation and apathy. Social skills deteriorate and there can be socially inappropriate behaviour, fatuousness, jocularity, abnormal sexual behaviour with disinhibition, or theft. Many patients are restless with an obsessive–compulsive and ritualized pattern of behaviour, such as pacing or hoarding. Emotional labiality and mood swings are seen, but other psychiatric phenomena such as delusions and hallucinations are rare. Patients become rigid and stereotyped in their daily routines and food choices. A change in food preference towards sweet foods is very characteristic. Of importance is the fact that simple bedside cognitive screening tests such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) are insensitive at detecting frontal abnormalities. More detailed neuropsychological tests of frontal function (such as the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test or the Stroop Test) usually show abnormalities. Speech output can be reduced with a tendency to echolalia (repeating the examiner’s last phrase). Memory is relatively spared in the earl stages, although it does deteriorate as the disease advances. Visuospatial function remains remarkably unaffected. Primary motor and sensory functions remain normal. Primitive refl exes such as snout, pout, and grasp develop during the disease process. Muscle fasciculations or wasting, particularly affecting the bulbar musculature, can develop in the FTD subtype associated with MND.”

Memory tests, mild cognitive impairment and dementia of Alzheimer type

Nobody can deny the undeniable benefits of a prompt diagnosis, when correct, of dementia, but the notion that not all memory deficits mean dementia is a formidable one. Besides, this tweeted by Prof Clare Gerada, Chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners, to me this morning I feel is definitely true,

A political drive, almost in total parallel led by the current UK and US governments, to screen older people for minor memory changes could potentially be leading to unnecessary investigation and potentially harmful treatment for what is arguably an inevitable consequence of ageing. There are no drugs that prevent the progression of dementia according to human studies, or are effective in patients with mild cognitive impairment, raising concerns that once patients are labelled with mild cognitive deficits as a “pre-disease” for dementia, they may try untested therapies and run the risk of adverse effects.

The idea itself of the MCI as a “pre-disease” in the dementia of Alzheimer type is itself erroneous, if one actually bothers to look at the published neuroscientific evidence. A mild cognitive impairment (“MCI”) is a clinical diagnosis in which deficits in cognitive function are evident but not of sufficient severity to warrant a diagnosis of dementia (Nelson and O’Connor, 2008).It is claimed that on the CANTABmobile website that:

However, the evidence of progression of MCI (mild cognitive impairment) to DAT is currently weak. It might be attractive to think that MCI is a preclinical form of dementia of Alzheimer Type, but unfortunately the evidence is not there to back this claim up at present: only approximately 5-10% and most people with MCI will not progress to dementia even after ten years of follow-up (Mitchell and Shiri-Feshki, 2009).

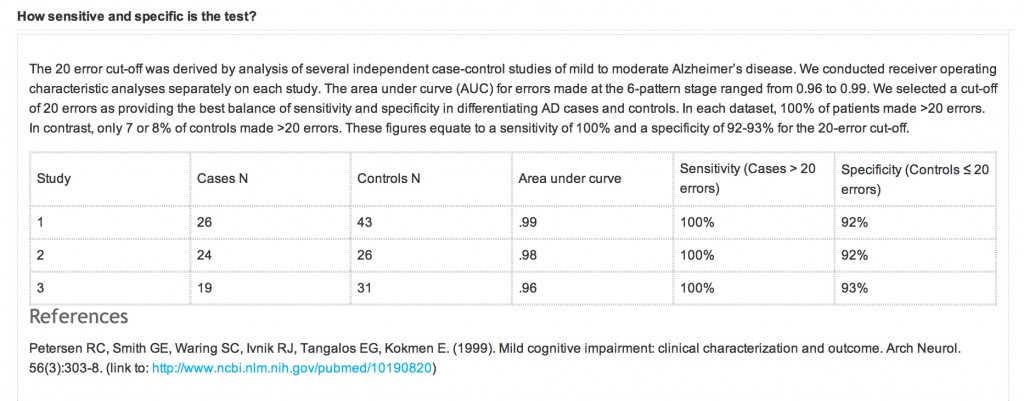

An equally important question is also the specificity and sensitivity of the CANTABmobile PAL test. Quite a long explanation is given on their webpage again:

However, the reference that is given is unrelated to the data presented above. What should have appeared there was a peer-reviewed paper analysing sensitivity and sensitivity of the test, across a number of relevant patient groups, such as ageing ‘normal’ volunteers, patients with geriatric depression, MCI, DAT, and so on. A reference instead is given to a paper in JAMA which does not even mention CANTAB or CANTABmobile.

NICE, QOF and indicator NM72

A description of QOF is on the NICE website:

“Introduced in 2004 as part of the General Medical Services Contract, the QOF is a voluntary incentive scheme for GP practices in the UK, rewarding them for how well they care for patients.

The QOF contains groups of indicators, against which practices score points according to their level of achievement. NICE’s role focuses on the clinical and public health domains in the QOF, which include a number of areas such as coronary heart disease and hypertension.

The QOF gives an indication of the overall achievement of a practice through a points system. Practices aim to deliver high quality care across a range of areas, for which they score points. Put simply, the higher the score, the higher the financial reward for the practice. The final payment is adjusted to take account of the practice list size and prevalence. The results are published annually.”

According to guidance on the NM72 indicator from NICE dated August 2013, this indicator (“NM72″) comprises the percentage of patients with dementia (diagnosed on or after 1 April 2014) with a record of FBC, calcium, glucose, renal and liver function, thyroid function tests, serum vitamin B12 and folate levels recorded up to 12 months before entering on to the register The timeframe for this indicator has been amended to be consistent with a new dementia indicator NM65 (attendance at a memory assessment service).

Strictly speaking then QOF is not about screening as it is for patients with a known diagnosis of dementia. If this battery of tests were done on people with a subclinical amnestic syndrome as a precursor to a full-blown dementia syndrome with an amnestic component, it might conceivably be ‘screening’ depending on how robust the actual diagnosis of the dementia of those individuals participating actually is. As with all these policy moves, it is very easy to have unintended consequences and mission creep.

According to this document,

“There is no universal consensus on the appropriate diagnostic tests to be undertaken in people with suspected dementia. However, a review of 14 guidelines and consensus statements found considerable similarity in recommendations (Beck et al. 2000). The main reason for undertaking investigations in a person with suspected dementia is to exclude a potentially reversible or modifying cause for the dementia and to help exclude other diagnoses (such as delirium). Reversible or modifying causes include metabolic and endocrine abnormalities (for example, vitamin B12 and folate deficiency, hypothyroidism, diabetes and disorders of calcium metabolism).

The NICE clnical guideline on dementia (NICE clinical guideline 42) states that a basic dementia screen should be performed at the time of presentation, usually within primary care. It should include:

- routine haematology

- biochemistry tests (including electrolytes, calcium, glucose, and renal and liver function)

- thyroid function tests

- serum vitamin B12 and folate levels.”

It is vehemently denied that primary care is ‘screening’ for dementia, but here is a QOF indicator which explicitly tries to identify reversible causes of dementia in those with possible dementia.

There are clearly issues of valid consent for the individual presenting in primary care.

Prof Clare Gerada has previously warned to the effect that it is crucial that QOF does not “overplay its hand”, for example:

“QOF is risking driving out caring and compassion from our consultations. We need to control it before it gets more out of control – need concerted effort by GPC and RCGP.”

Conclusion

Never has it been more important than to heed Prof Brayne’s words:

“As a group of clinical and applied researchers we urge governments, charities, the academic community and others to be more coordinated in order to put the policy cart after the research horse.”

In recent years, many glib statements, often made by non-experts in dementia, have been made regarding the cognitive neuroscience of dementia, and these are distorting the public health debate on dementia to its detriment. An issue has been, sadly, a consideration of what people (other than individual patients themselves) have had to gain from the clinical diagnosis of dementia. At the moment, some politicians are considering how they can ‘carve up’ primary care, and some people even want it to act as a referral source for private screening businesses. The “NHS MOT” would be feasible way of the State drumming up business for private enterprises, even if the evidence for mass screening is not robust. The direction of travel indicates that politicians wish to have more ‘private market entrants’ in primary care, so how GPs handle their QOF databases could have implications for the use of ‘Big Data’ tomorrow.

With headlines such as this from as recently as 18 August 2013,

this is definitely ‘one to watch’.

Further references

Beck C, Cody M, Souder E et al. (2000) Dementia diagnostic guidelines: methodologies, results, and implementation costs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 48: 1195–203

Mitchell, A.J., and Shiri-Feshki, M. (2009) Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia -meta-analysis of 41 robust inception cohort studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 119(4), pp. 252-65.

Nelson, A.P., and O’Connor, M.G. (2008) Mild cognitive impairment: a neuropsychological perspective, CNS Spectr, 13(1), pp. 56-64.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2006) Dementia. Supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. NICE clinical guideline 42

Many thanks to @val_hudson for a useful critical comment about an earlier version of this blogpost.

Shibley’s CV is here.

Are the corporates holding the NHS to ransom?

In terms of political campaigning, the message that the NHS ‘reforms’ were unelected or undemocratic, and cost the ‘hard working taxpayer’ billions, is admittedly quite a good one. As political market positioning, however, this puts the #NHS in roughly the same place as an illegal war in Iraq, or a change to the GCSE examination system, or High Speed 2. It has always felt that the motivator of the ‘people being lied to’ is an apt one regarding the “democratic deficit”, and this is after all theoretically and pragmatically why millions do not vote every General Election. However, the disillusionment of voting for any political party is possibly equally divided amongst all political parties, with some more so than others, with Tory voters wondering how and why Mid Staffs and Morecambe Bay could have happened under Labour’s watch, and Labour voters wondering how the Liberal Democrats could have used weak arguments about competition law and ‘integration’ to ramraid section 75 in the House of Lords.

Whichever side of the fence you sit on regarding the ‘corporate capture’ of public health in this jurisdiction, whether you’re talking about standard packaging of cigarettes or minimum alcohol pricing, it is clear that the Health and Social Care Act (2012) has changed the landscape. Like an asteroid from outer space, it’s in a way intriguing how and where the Health and Social Care Act (2012) came from. Indeed, the vast majority of contracts awarded under ‘section 75′ and its equally notorious Regulations to the private sector is a testament to the efficacy of a policy which transfers resources from the public to the private sector. Part of the argument against this has been that the private sector introduces a level of repetition, waste and inefficiency substantially more than the public sector in healthcare, and the conceptualisation that there is a real ‘market’ in the NHS is an academically faulty one. A second part of the argument that this is tinkering with, to an enormous detriment, with an important societal institution of England which is held in much respect. A similar argument has been given for why Oxford and Cambridge should be given so much reverance as institutuions in the education sector and budget, when it might be more fitting that the devotion to them is manifest through the culture and heritage budget. But like Oxbridge daily, a huge number of real ‘transactions’, though perhaps not “millions”, takes place. The NHS might be a ‘sacred cow’ for some, but it is equally a powerful brand. Andy Burnham says rather mischievously that he does not wish the NHS to become, simply. a “blue and white logo”, or words to that effect, but the power of the NHS brand is illustrated that outsourcing of NHS services is done under the powerful NHS brand with massive brand loyalty.

The outsourcing of NHS services, and indeed exporting of NHS services, is part of the phenomenon where successful governments have wished to make ‘the NHS work pay’, i.e. the “hard working” NHS can pay its own way in modern England. Even better, it can ‘pay its bills’ but drawing a little salary of its own. Granted that the income might not be as huge as £20bn of Nicholson/McKinsey savings, but essentially the right wing do not like this fundamental shift of emphasis. The “change of agenda” of the NHS is prone to be dressed up as a ‘conspiracy theory’ by members of the UK Labour Party, but it is a statement of fact that the statutory purpose of directors of companies under English law is to promote the success of the company; success is defined narrowly as generating a shareholder dividend. This lends itself to the idea that private companies fulfilling NHS functions, such as domestic or multinational corporates, might be a ‘good investment’ as part of an investment portfolio, returning good profit for relatively little risk. That logic is, of course, not that daft, given that the privatised NHS market is an oligopoly, to be occupied by the usual suspects. Privatisation is inherently unpopular now with the English voting public, and the current government has put rocket boosters on a privatisation policy which has been advancing under both Labour and the Conservatives. Like energy, or broadband, despite a purported wish to ‘lower barriers to entry’ and to reward ‘value for money’ and ‘innovation’, and the usual rhetoric of Conservative memes, the contracts go to the same people, often with ongoing allegations of fraud, to deliver the same unconscionable profit for directors and shareholders for offering roughly the same ‘goods and services’ in the same crowded markets.

The ‘campaign’ against the Health and Social Care Act (2012) therefore rumbles on, and is likely to do so until the inevitable General Election to be held on May 7th 2015. Ed Miliband has successfully done what many Labour politicians have feared to do previously, and that he is: set himself the agenda, and decide to follow through his arguments. This is of course in total contrast to Lord Mandelson, who was the future once, like Lord Digby Jones, who have been fast to take to the airwaves to rubbish Ed Miliband.

But the res ipsa loquitur – this is a popular, populist policy, which has public backing, based on sound economic and legal arguments, with a clear policy motive (of delivering genuinely good value for the customer rather than high profit for a corporate). nPower has responded yesterday “a sop to Ed”, which arguably assumes that a Miliband government is a vaguely realistic possibility. Another item of evidence that a Miliband government is a realistic possibility has been the effect that this policy has had on the share price of utilities, so much so had leaks of this policy been leaked to the public ahead of the official announcement Team Miliband might have offended in civil law the use of financially sensitive information in our jurisdiction.

The damage of the ‘corporates holding the country to ransom’ narrative could be more damaging than one first expects, and this is for a number of reasons. Firstly, it is widely held, at least in political circles, that the Cameron/Clegg government is much more corporatilist than the previous Thatcher Conservative administrations, and that Cameron/Clegg have gone ‘further and faster’ than would have been possible under the likes of Thatcher, Bottomley or Ken Clarke. Secondly, the question of who drives policy is still a ‘slow burn’ issue, thanks to the successful endeavours of “38 degrees”, “Spinwatch” and “Social Investigations” (inter alia). Whilst the notion of the Unions having ‘beer and sandwiches’ is of historic interest perhaps, and indeed David Cameron would still like to whip people up into hating the unions through mechanisms such as the Lobbying Act, the mud sticking from how hedge funds appear to have called many shots in health policies is not that pleasant. This second issue of stakeholder involvement is a critical one, in that the public, even if they have horrific members of the late 1970s ‘Winter of Discontent’, have a sentiment that public sector nurses ‘do a valuable job’ and that individual membership of a Union is a democratic and laudable right.

Thirdly, the oligopoly of private provider corporates do stand, and have benefited, from the Health and Social Care Act. So this is not a question of idle speculation about privatisation – this is privatisation which is much further advanced than, for obvious reasons, Royal Mail, though the political spectacle of floating the NHS on the London Stock Exchange or AIM market is not one either main political party should currently like to entertain. Fourthly, and possibly most importantly, is the idea that the corporates on this occasion have ‘overplayed their hand’. Angela Knight, whom many people will remember for defending the behaviour of the equally uncompetitive and unpopular bankers, has been sent into battle to talk about ‘blackouts‘ and impending disaster through the short time window in which corporates can, instead, demonstrate to the rest of society that they are indeed good corporate citizens and worthy of public trust and respect. This idea of foreign-owned corporates ‘turning the lights out’ on England has of course gone down like a lead balloon, and will be in the subconscious linked to unions ‘refusing to clear rubbish up’, and so forth. The one big problem here is that Unions represent democratic bodies, but hedge funds do not.

And, finally of course, is the idea of who actually has economic, social and political power in England. Members of unions are indeed the backbone of making the NHS function (take for example UNISON’s campaigning of safe nursing staffing levels), and therefore have a legitimate say in how to ‘performance manage’ the NHS. Where frontline employee-employer relationships has been poor has been to the clear detriment of places within the service, such as the union dispute in Hinchingbrooke. The argument that there is essentially nothing wrong with transferring ‘public’ functions of the NHS to the private sector is undermined by the initial findings that David Nicholson has already had to grapple with hard-nosed issues of where competition law has been to the detriment of patient clinical care, and that any real-time underfunding of the NHS is likely to lead to backdoor rationing of services within the NHS. The ultimate merging of universal credit, ‘whole person care’ and individualised budgets could be the ultimate policy plank for any party to transfer the State duty to provide a comprehensive, free-at-the-point-of-need, universal service to one where the individual/budget holder makes his own mistakes and good budgetary decisions (and takes full responsibility for him- or her-self). As the debates about the East Coast railway and the privatisation of the Royal Mail demonstrated this week in Brighton. the idea of state-run services are popular with Union members if not with the predominantly social-democratic ‘for the public good’ members of the Labour Party leadership.

‘One Nation Labour’ can be sold, and indeed has been sold, as a doctrine where no vested interest takes control, and this is important for the three planks of Ed Miliband’s approach, economy, society and the political process. However, the NHA Party with protagonists Dr Jacky Davis and Dr Clive Peedell might equally wish to argue that the only final way to break free from this political ‘tug of war’ would be to ‘allocate your resources’ in a party focused on sorting out the NHS. They might argue that all the major parties have policy ‘blood on their hands’, e.g. the ‘private finance initiative’ proposed by Tory David Willetts in 1993, elaborated on in a major Tory thinktank in c.1997, wave of PFI contracts from Coopers and Lybrand just before Blair came to power, and further implementation of PFI under Gordon Brown and George Osborne. The concept of ‘corporates holding the country to ransom’, which the BBC and smaller media providers find hard to cope with, is an attractive one for many ‘ordinary’ voters who feel altogether disenfranchised from the political process, especially on the NHS.

If, on top of that, the notion that corporates “holding the NHS to ransom” curries favour with members of the general public ahead of how represented in the main media, Ed Miliband could find himself with the political movement on the NHS he has so long yearned for. You can already see the seeds of these theme being sown by Andy Burnham MP in his main speech to Conference in Brighton in 2013, and in subsequent copy (for example, in the Mirror or the Belfast Telegraph) that the NHS is turning into the failed system of US-style hospitals. For policy wonks, the comparison with US-style hospitals is particularly sensitive, given how Kaiser Permanente has been touted by some powerful and influential as a paradigm to follow, e.g.

Conclusion The NHS can learn from Kaiser’s integrated approach, the focus on chronic diseases and their effective management, the emphasis placed on self care, the role of intermediate care, and the leadership provided by doctors in developing and supporting this model of care.”

This is not just an issue of domestic politics, as at the moment there is no sign that the Conservative government wishes to scrutinise even the US-EU free trade agreement, regarding the ‘status’ of the NHS. The fight goes on.

Shibley’s CV is here.