Home » Posts tagged 'GMC'

Tag Archives: GMC

The perfect storm around #BawaGarba was a long time coming

As a result of my erasure in 2006 from the register of medical professionals in the UK, I had a lot of time to reflect on the events leading up to it. I have from time to time also reflected on this following my restoration in 2014. In the meantime, I had re-trained in law, paradoxically inspired by my experience of the judicial process. This was not a brief Masters in medical law, but both my Bachelor and Masters of Law, as well as the pre-solicitor training course. To do the last bit, I had to be approved as a fit and proper person by the legal regulator, the Solicitors Regulation Authority. I enjoyed my study of the English legal system, and reflect that if I had never studied law I would never have met the late Prof Gary Slapper – a formidable academic with an interest in conspiracy theories and corporate manslaughter.

This is all rather awkward, not least because Charlie Massey and Jeremy Hunt get on well, despite having divergent views on the implications of the #BawaGarba judgment. In a way, the General Medical Council (GMC) does not actually do ‘personal’, although ensuing events do rather appear like a hate campaign. It has become traditional to issue a sop to the ‘victim’ of misfeasance of a Doctor, and I do genuinely feel that there can be few things worse than the mental anguish of a grieving relative. The GMC and Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service maintain separation of powers, and, whilst I feel that the GMC can move in mysterious ways, I feel that the GMC believe that they are doing their very best to maintain public safety and confidence in the medical profession. This blogpost is therefore not an easy one to write, and inevitably will mean that I could accidentally cause offence. I am reflecting on issues to the best of my ability, and, if I fall short, I do apologise.

#BawaGarba found herself in a perfect storm. There are various systemic factors arguably out of direct control of the GMC. These are the exact funding of the NHS, including whether there is a sufficient number of doctors on rotas in individual hospitals. Notwithstanding, the GMC has a statutory duty in education and training, and, from what I know, will intervene in cases where NHS Trusts offer a suboptimal training experience. But there are important other systemic factors. It is quite common for non-white British trainees, once a GMC alert has been triggered, to be ‘thrown to the wolves’ from the regulatory process, but whether this achieves statistical significance is worth exploring. The trend has been for, once these Doctors have been reported, for all positive references to be withdrawn, and, often, although the source of the leaks are never identified, for the Doctors to receive a barrage of unfavourable press prior to any hearing. A media presence seems to defy any traditional notion of contempt of court, or right to a fair trial, as Doctors are subject to a total monstering and humiliation in the media. But it is not uncommon for papers in the English media, and their class of readers, also to subject groups of Doctors, such as EU Doctors, to an utter monstering as well, allowing xenophobia and outright racism to flourish. The scope for moral panic is enormous. But to lay these problems at the foot of the GMC, I feel personally, is unfair.

The GMC indeed also has an important statutory duty for patient safety under section 1 of the Medical Act 1983. The “There but the grace of God go I” used alarmingly frequently by white, English doctors on Twitter might reflect the observation that some Doctors are safer from attacks from institutional racism than others. This is particularly problematic if the NHS Trusts continue on its trend to trigger an official regulatory complaint effectively to cover their own backs rather than a genuine attempt to improve the performance, health and wellbeing of their Doctors employed under employment contracts. This has indeed been witnessed in the enforcement of the junior doctors’ contracts, arguably. Also, the “There but” observation is also problematic from the point of view that it seems to signal an admission that registers an admission that registered Doctors go to work knowingly taking risks and making mistakes. Most Doctors will admit to having taken risks and having made a mistake, and the number of mistakes reported daily in the NHS, a mere fraction of the real number, must urge a need for an open and transparent culture where people can learn from mistakes. But the GMC and the higher courts will tend not to tolerate any mistakes, or catalogues of error, whatever the mitigating factors. This might include an unblemished record for 30 years. The issue is that if the performance is way below a standard, there can be no excuse for it. If somebody has died, the threshold for mitigation has to be high, most reasonable persons might argue. And if a court of law has found someone guilty of manslaughter, whatever the process involved for doing so or the people involved, it is hard to leave no sanction on the Doctor, it is argued, whatever the need for organisational learning. Both the GMC and higher courts have consistently argued that public trust and confidence in the medical profession are more important than any individual doctor’s career.

The argument that ‘We go to work and are caught between a rock and a hard place’ merits scrutiny too. This comes down to the nature of how a crime is satisfied in English law – there can be intention to do the crime, and, although there is some finesse about the jurisprudence, there might be recklessness. The law in this is fairly well settled since R v Adomako. It might seem unfair to blame a Doctor having to cover seven bleeps one morning, but the point in law is that the Doctor by carrying those bleeps has assumed a duty of care to his or her patients, and any breach therefore of this duty of care, given the issues of causation and remoteness, is negligence. It might be argued that in tort the Doctor has assumed this responsibility under duress, but in reality most Doctors pick up the bleep from an office in the Hospital without any altercation. And Doctors are entitled to resign if they feel that there has been a fundamental breach of a contract, including a bilateral feeling of trust and confidence, between employer and employee. In reality, Doctors never do, despite the potential risks for patient safety.

Whilst there might be outrage about the lack of due emphasis on organisational learning, this organisational learning nor indeed any individual duty of candour are operational at any meaningful statutory level, meaning they exist in an Act of parliament or statutory instruments. And nobody is above the law. If there had been no sanction on #GawaBarba, a possible interpretation might have been that mistakes, whatever the reason, are excusable because of the ‘state of the NHS’. It might then be argued that the correct course of action might be for corporate manslaughter against the Secretary of State for health and social care, for ‘avoidable deaths’, but this has to be proven beyond reasonable doubt – an incredibly difficult offence to fulfil, as the late Prof Gary Slapper I am certain would testify.

I doubt, if #BawaGarba finds herself back on the GMC Register, she will find it easy to find employment again, especially with at least a five year gap in training. The GMC, even with its statutory duty for education and training, as well as patient safety, seems pretty indifferent to the professional rehabilitation and retraining of Doctors put back onto their Register. But the observation that no Doctor can ever be professional rehabilitated does concern me, even with the strong emotions that the ‘punishment should fit the crime’, and the need for a scalp can be overwhelming. For example, #BawaGarba has found that her subsequent good performance had become somewhat irrelevant as far as the regulator and higher courts were concerned.

As the old trope provides, there are no winners. There are only losers. It’s said that the GMC ‘doesn’t do personal’ in the same way a sanction is delivered in the same way a parking ticket is issued, and the GMC’s purpose isn’t, it is argued, to do ‘show trials’. The GMC’s position is that they are not in the business of ‘punishing Doctors’, but, I feel, it is of concern that unintended consequences, including a culture of fear, could continue to be dominant in the medical profession. The GMC doesn’t likewise, perhaps reflecting their perceived concerns from the general public, want to allow free rein on Doctors ‘free to make mistakes’, and good doctors will argue that they are all trying to do the job to ‘the best of their abiility’. The problem facing the GMC is whether ‘the best of someone’s ability’ is simply good enough. The general approach is that there is no shortage of doctors, and it is a honour to be a registered doctor. Whether there is a sufficient number of doctors for the demand is a concern the GMC can decide to involve itself with, or not. There is a clause in the code of conduct – Good Medical Practice, 2013 – stating that it is the responsibility of doctors to identify any shortfall of resources. I doubt all the senior Consultants or even STs in training taking to Twitter outraged about the #BawaGarba judgment are writing this morning to the GMC to warn about shortage of resources in their own hospitals, despite concerns about patient safety. It is noteworthy that the GMC in their statement on the case mentioned this only yesterday even. But individual Doctors have also been rather effective at protecting their own backs?

The GMC will know what is wrong with their fitness to practice procedures for unwell doctors

The GMC are conducting a review into their ‘fitness to practise’ FTP, procedures.

The independent review into deaths of Doctors who have been on their Register, awaiting FTP, is about to be published soon one hopes.

I have decided to write the GMC a last minute contribution to this consultation.

I am on currently on the Medical Register, having been erased from it in 2006/7. It is beyond reasonable doubt that I was severely ill with an alcohol dependence syndrome.

You’ll get fewer people than me wishing the GMC well, still.

I feel that the support for unwell Doctors in the National Health Service, and any hunger for scalps of Doctors will feed into this.

The question is whether the GMC can fit itself into a wider system of learning from mistakes and also supporting Doctors ‘in trouble’.

I have learnt much from my time, not least becoming into recovery from alcoholism, and being physically disabled for the first time.

But I thought it would be incorrect not for me to make some polite views known. As I say, I wish the GMC well. I am also regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority, so I will expect the GMC to obey a new Act of Clinical Regulation if it comes into law pursuant to the English Commission’s proposals.

General Medical Council

3 Hardman Street

Manchester

M3 3AW

Dear Sir

Re GMC Consultation over fitness to practice procedures

It is with interest I have been following your consultation over fitness to practice (FTP) procedures for the medical profession.

I have thus far tried to keep out of these discussions. I myself was only restored to the medical register earlier this year pursuant to a full Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service (MPTS) panel hearing. I can say with all honesty that being returned to your Medical Register was the happiest moment of my entire life. I consider a massive honour to be there now, and indeed became quite tearful taking about it at the recent BMA Careers Fair held in North London a few weeks ago.

My regulation with the General Medical Council (GMC) has been simultaneously ‘the best of times and the worst of times’. I had resisted of commenting on it, because I can hardly been said to have been detached from the processes. But I have gone through the full regulatory loop.

I also have, since my erasure in 2006, re-trained in law, having even obtained a Masters of Law. I feel that proportionality runs like letters through a stick of rock in all the work the legal profession does. Balancing competing interests is what lawyers do. It is what the GMC has done since 1858, reflected as well in your current tagline.

I have also, as explanation, successfully completed a MBA. I decided to study an area called ‘performance management’. I don’t feel this term is particularly helpful, but the discipline has a lot to offer both the legal and medical profession. I had become regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority back in January 2011, following a full due diligence procedure.

At the outset, I should wish to apologise for this short note. But I was moved by your current Chair, Prof Terence Stephenson, who told an audience of us at the Practitioners Health Programme in Swiss Cottage, London, that change is totally possible; however, it tends to be ineffective through loud criticism from the sidelines.

That is why I wish to address your concerns head on.

I feel personally my erasure was completely correct. In response to the Chairman of my MPTS panel who asked me whether my time had ‘gone badly’, I disagreed; I said “it was a complete disaster”.

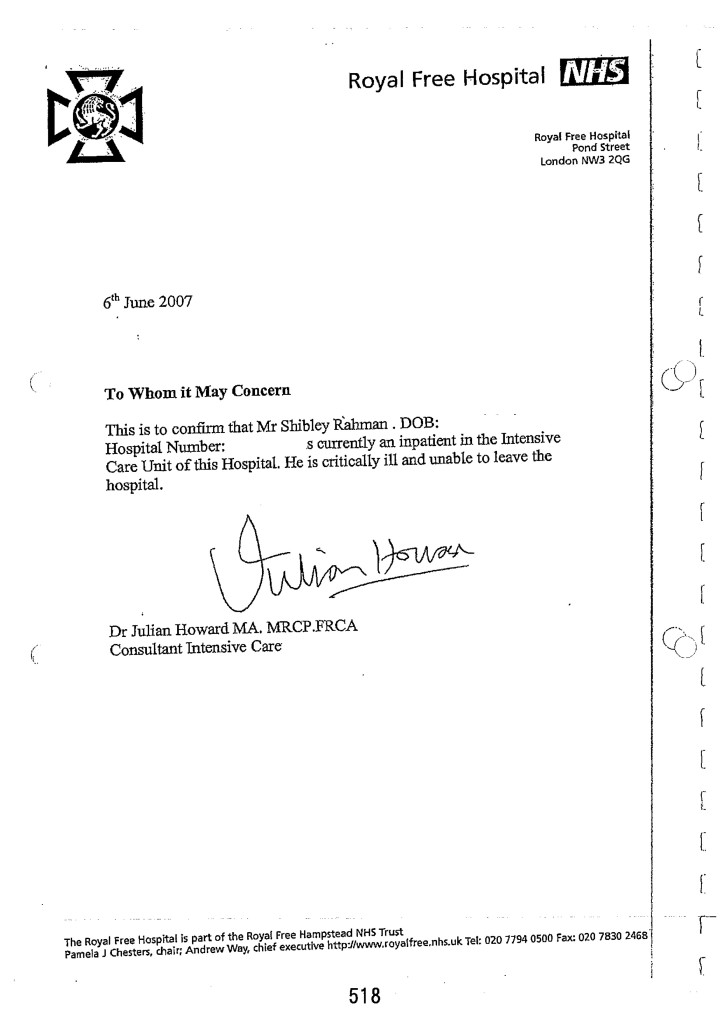

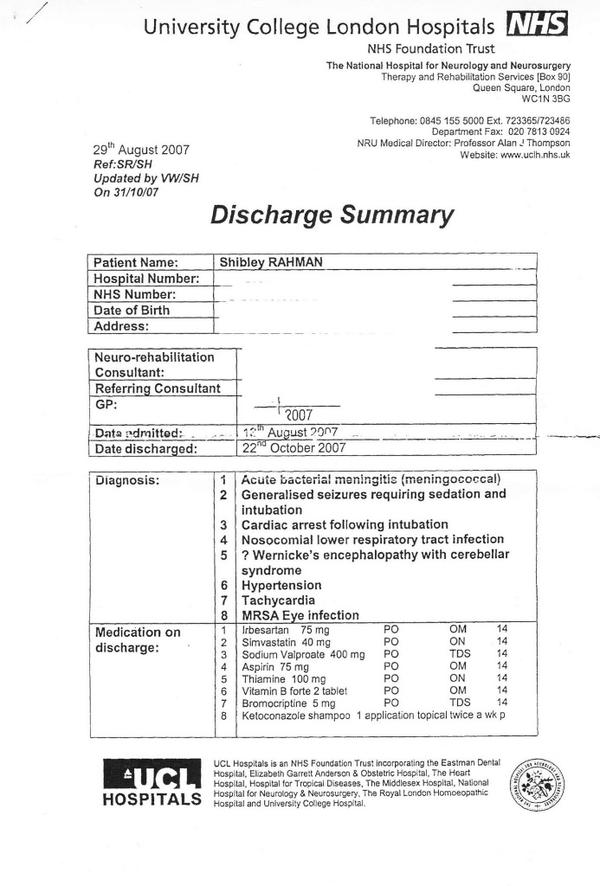

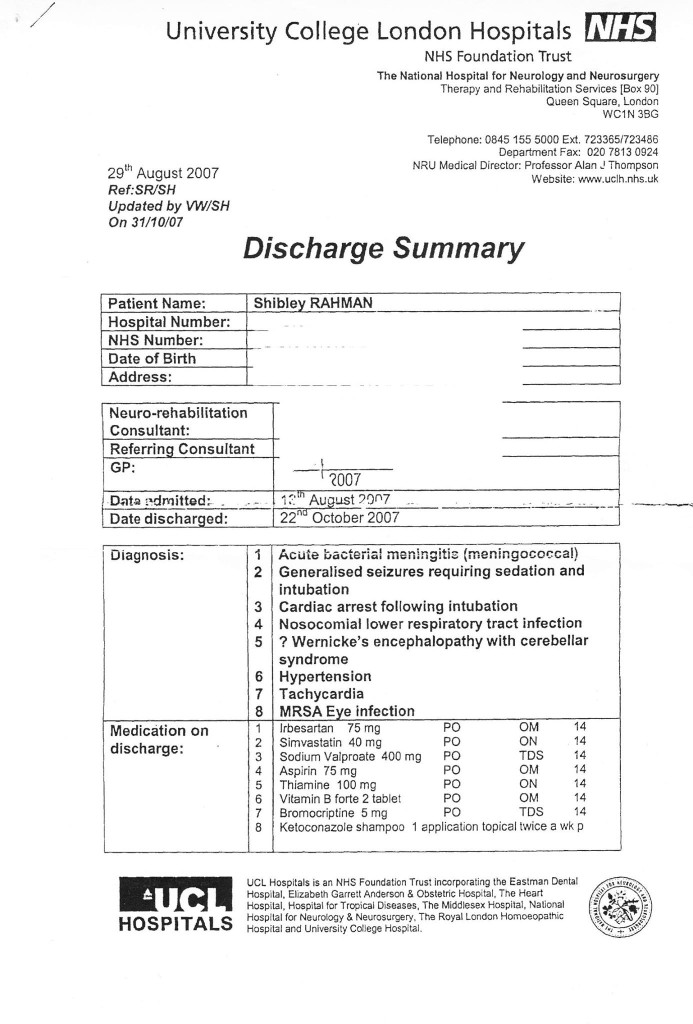

Nearly a year after direction to erasure, in 2007 June I was blue lighted into the Royal Free Hospital. I had a cardiac arrest and epileptic seizure, with a rampant acute bacterial meningitis. I was then kept on life support for six weeks. I became physically disabled. The NHS, though, saved my life.

I have now been in recovery for seven years at least. I do not in any way condone the events which led to my erasure, but in law I believe that ‘but for’ my alcoholism these events would not have happened.

The direction of travel seems pretty clear. Despite a temporary stalling in the response to the English Law Commission, I feel it is likely the proposals for a root and branch reform of clinical regulation will take place shortly. I full support Niall Dickson in this.

Patient safety is paramount. But the balancing of competing interests is not the reputation of Doctors or the reputation of the regulator, but rather the needs of the patients compared to Doctors trying to do their professional work.

It is often forgotten that many Doctors feel mortified if they make a mistake. But the sheer volume of medical mistakes made daily, for example in medication errors, makes it untenable that every doctor who has ever made a mistake should face a tough public sanction.

Furthermore, cracking down too heavily on Doctors in the medical profession is completely countercurrent to the drive to learn from mistakes in the NHS. There should be a learning culture, and in the drive for quality complaints should be acted upon as gold-dust.

I have every confidence that a well respected medical profession will be possible through a well respected GMC. Ensuring high standards in medical profession is not only achieved through regulation. It will only be possible if seniors in the medical profession show leadership as to the skills they wish to see flourish in the health and care sectors.

There is no doubt for me that the investigations process is too long. There are clear ways in which the GMC departs from the standard English law (e.g. regards costs, telling you how long investigations will take, ambiguities in the civil standard of proof of applied). During that time, the mental health of certain Doctors appearing before the GMC will markedly deteriorate due to stress. Low self esteem is a massive problem in people like me who have faced alcoholism or, in the case of others, other substance misuse problems. When you add to this the trial by media which is out of the GMC’s control, the perfect storm can be utterly disastrous.

One of the principal ways in which the GMC departs from the law currently is how there is little emphasis to manage disputes at a local level. Mediation and arbitration is very important under the civil procedure rules of English law, prior to litigation. The GMC approach is adversarial.

I should like enforcement of the current code of conduct, with a view to solving problems rather than publicly sanctioning Doctors as the key priority, to be important. The enforcement of the national minimum wage, for example, has proved problematic, despite it being a very good piece of legislation. Likewise, one can easily argue that requirements for Doctors to express concerns about inadequate resources, or a duty of candour, are already enshrined in the code of conduct, and have been so for many years now.

I mean my short note with complete goodwill. The GMC has an incredibly important function to perform. I am currently under two professional regulators. Since my erasure, I have spent 7 years in recovery, nearly finished five books and graduated in three degrees and one diploma, so rehabilitation is perfectly possible in my view.

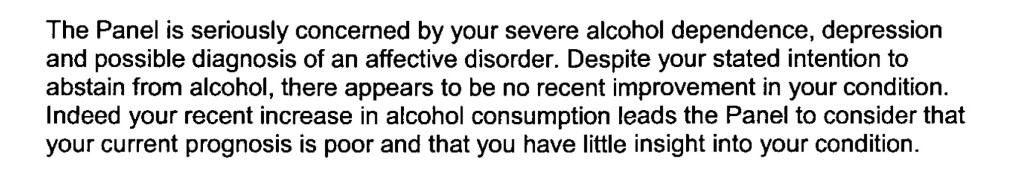

As such it’s going to be impossible for the GMC to ‘do outreach’ as regards the health of Doctors. I openly admitted to your MPTS panel that I failed in not putting myself under a GP. I worry about junior Doctors who are worried to seek help over medical issues, because of concerns about their careers. Patient safety is paramount. During time of a lengthy investigation by the GMC, with mental illness not under control, a Doctor due to be appearing in front of you can go from poor health to catastrophic health. They can become in total denial and lack insight.

Whilst I will note why you may not wish to ask about health issues because of various statutory instruments in the English law, one might consider whether it might be proportionate for there to be a ‘middle man’ overseeing sick Doctors. This is essential for separation of powers between the regulator and the regulated. The Practitioners Health Programme and Doctors Benevolent Fund deserve national resourcing. This is not solely an economic case; it is a moral one, I strongly feel.

I trust the GMC will act impressively in response to these demanding issues in due course. Please do not hesitate to contact me should you need to.

Kind regards.

Yours faithfully,

Dr Shibley Rahman

cc [REDACTED]

The GMC needs to be a good citizen too

The topic of how corporates act as ‘good citizens’ has been significant in recent years, for example the synthesis of work on strategy and society.

Broadly speaking, this work has identified a number of different concepts which are vital to corporate social responsibility.

The first is a ‘moral obligation’.

This must include honesty and integrity, and directly relates to domain 4 of the code of conduct “Good medical practice” for standards in trust and probity from the “General Medical Council” (GMC). Moral behaviour and legal regulation are dissociable. A legal ‘duty of candour’ or ‘wilful neglect’ are enforcement mechanisms for people telling the truth and protecting against deliberate malicious behaviour. But these are undeniable moral imperatives too. If the clinical regulator finds itself in dealing with a case in an unnecessarily protracted length of time which is disproportionate to reasonable standards, the clinical regulator should make an appropriate apology, ideally.

Sustainability is important if the clinical regulator is to be ‘in the long game’ rather than grabbing headlines for being seen to be tough on misfeasance from individuals. This means in reality that the clinical regulator should be sensitive to the environment and ecosystem in which it operates. If it is felt, for example, that politically and economically it is expedient to pursue ‘efficiency savings’, the regulator must have a sustainable plan to ensure that it is able to ensure that such savings do not impact on patient safety. The raison d’être of the GMC is supposed to be promote patient safety. A proportion of the Doctors will be unwell. The legal precedent is that conduct which is so bad cannot be condoned whatever the reason. However, it is also true that ‘but for’ alcoholism, for example, certain problems in misconduct and poor performance would not have occurred. An ill doctor is about as much use economically as somebody out of the service entirely, so it is an economic sustainable argument that the health of doctors should be an imperative for the NHS. A ‘patient group’ within the GMC would go a long way to demonstrate that the GMC is capable of playing its part within a wider ecosystem. I know of no other important entity which does not have one.

Thirdly, there should be a license-to-operate. This cannot be overstated. ‘Mid Staffs’ commanded much momentum in the media which was a problem for both the medical profession and its integrity, and yet there is still an enduring issue whether the GMC were able to regulate this as best they could under the confines of the English law and codes of practice. The GMC are also yet to report on the deaths of Doctors awaiting Fitness to Practise hearings, and the outcome of this will be essential for Doctors to ‘buy in’ literally into wishing to pay their subs.

Last of all is reputation. This goes beyond the popularity on a Twitter stream. At the moment, there is concern that neither the medical profession nor the public feel very satisfied about the performance of the GMC. There is uncertainty what the public perception of the GMC is; many feel that it is a general complaints agency, when it is, in part, to regulate the performance of individual Doctors. There’s no statutory definition of what ‘unacceptable misconduct is’, and hugely relevant to the reputation of the medical profession. This had been addressed in the English Law Commission’s proposals for regulation of clinical professionals, which are yet to see the light of day. Without this definition, the GMC can simply come down heavily on behaviour which it feels is embarrassing with impunity, whatever the potential other contribution of that doctor might be. It is quite unpredictable what the consistent set of standards where members of the public feel wronged might be for this; the GMC is very unwilling to be seen as a ‘light touch’ against members of the public who want tough sanctions.

There are so many aspects how the GMC could demonstrate its willingness to be a good citizen, which could help with the four points above. I feel as a person who has been through the whole cycle of having been regulated, who takes his credentials of being a NHS patient and being a student lawyer regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority rather seriously, there are constructive ways to move forward.

Firstly, I would like to see a ‘user group’ of Doctors who’ve been through the regulatory process, and who have had bad health, who might wish to volunteer on helping the GMC with improving its operational output. Secondly, I understand the temptation to throw ‘red meat’ at the readership of certain newspapers. But likewise, the GMC could make more effective use of local dispute resolution mechanisms, looking at what the Doctor, the Trust and the member(s) of the public would like as a compromise to problems. This could have the aim of having a Doctor where reasonable corrective action has taken place finding himself or herself being able to return to work. The current situation has evolved through history as being adversarial, and this can err towards catastrophising of problems rather than wishing to solve them. Likewise, there is a public perception that some issues are completely ‘shut down’ before any attempt to investigate it. Thirdly, the GMC must be aware, I feel, of the evolving culture and landscape of the medical profession across a number of jurisdictions. This means the GMC, patients and professionals could be, if they wanted to, united in their need to uphold the very highest standards of patient safety. Clinicians work in teams, and techniques such as the ‘root cause analysis’ have as an aim finding out where the performance of a team has produced an inadequate outcome. Furthermore, there is no point in one end of the system urging learning from mistakes and organisational learning with the other end of the system cracking down heavily on individuals, with the effect that some individuals never work again.

Like whole person care in policy, the clinical regulator should be concerned about all the needs of an individual, including health needs, public safety promotion, and the needs of the service as a whole. I have every confidence that the GMC can rise to the challenge. It’s not a question of light touch regulation, but the right touch regulation.

And, as per medicine, sometimes prevention is better than cure.

It is a massive honour to be able to return to the GMC Medical Register. A dream come true.

Yesterday, I went for lunch with my friend and colleague, Prof Facundo Manes. Facundo kindly wrote a Foreword to my book ‘Living well with dementia”, an essay on the importance of personhood and interaction with the environment for persons living with dementia. We were just a stone’s throw from all those bars and pubs in Covent Garden I knew well in a former life.

I spent nine years at medical school, and very few as a junior doctor.

I’ve now been in recovery for just over seven years.

But in that time I do remember doing shifts starting at Friday morning and ending on Monday night. I remember the cardiac arrest bleep in Hammersmith at 4 am, and doing emergency catheters at 3 am in Norfolk.

I had an unusual background. I loved medical research at Cambridge. In fact, my discovery how to diagnose the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia is cited by the major international labs. It is in the current Oxford Textbook of Medicine.

Being ensnared by the General Medical Council in their investigation process devastated my father. He later died in 2010. I remember kissing him goodbye in the Intensive Care Ward of the Royal Free, the same ward which had kept me alive for six weeks in 2007.

I of course am completely overwhelmed by those events widely reported, especially in the one in 2004. The newspapers never report I was blind drunk. The media when they do not mention my alcohol dependence syndrome are missing out a key component of the jigsaw.

Until I die, I will never be safe with one alcoholic drink. I will go on a spiral of drinking, and that one event I am certain would either see me in a police cell or in A&E.

One event did change my life. I was blue lighted in, after a year of heavy drinking after I was erased by the GMC in 2006, having had a life-threatening epileptic fit. The crash team attempted emergency intubation, but I ended up having a cardiac arrest which was successfully resuscitated.

I do not wish to enter any blame games about what happened a decade ago. It turns out that the Trust which reported me as dishevelled and alcoholic, and having poor performance simultaneously, is in the Daily Mail this morning for a running a ‘chaotic’ A&E department.

It also turns out that another Trust in London which reported me as dishevelled and alcoholic, and having poor performance simultaneously, had its A&E department shut down this week.

I have written previously here about my experience as a sick doctor.

I was in denial and had no insight. Hindsight is a wonderful thing, but I needed sick leave and a period of absence and support. But I do not wish to blame anyway for those events I wish had never happened some time ago.

But the GMC referrals were absolutely correct. I had a proper medical plan put in place for me when I awoke from my coma. I followed religiously my own GP’s advice too.

I am now physically disabled, and have had no regular salaried job since 2005. But I am content. I live in a small flat with my mother in Primrose Hill. I regularly go out to cultural events. I maintain my interest in dementia, going to a fourth conference this year for Alzheimer’s Europe in October, where I have been chosen to give one of the research talks. It’s actually on an idea which David Nicholson inspired me over.

I’ve done four books on medicine, including one on living well with dementia. The Fitness to Practice panel in their judgment note my contribution there, which I am pleased about.

The Panel also crucially made the link in their judgment that my poor performance in conduct and competence coincided with my period of illness, the alcohol dependence syndrome, for which I am now under a psychiatrist.

I go to AA sometimes, and the weekly recovery support group at my local hospital. Being in contact with other people who are starting the same process of getting their life back continues to inspire me. I also attend the suspended doctors group for the Practitioner Health Programme, which helps me understand myself too.

I believe that there is no higher law than somebody’s health. I understand the pressures of why trainees preventing them from seeking help in the regulatory process.

But I do have an unusual perspective. First and foremost, I am a patient myself, and proud of it.

Secondly, I am regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority. I can become a trainee solicitor, if I want to be. I had a careful due diligence process in 2010, and I thank the legal profession for rehabilitating me.

Thirdly, I will now be regulated once again by the General Medical Council pending a successful identity check on October 7 2014. Having my application to be restored to the UK medical register is a massive honour for me. I caused a lot of hurt to others during my time with the medical profession last time, and this time I would like things to be different, and be of worth.

This, I hope, will mean a lot to my late father.

I am grateful to all the people at the Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service, and to the GMC prosecutor for presenting a fair case on behalf of the GMC who need to promote patient safety.

I am encouraged that the GMC’s new Chair, Prof Terence Stephenson, “gets” change for the better for the profession, and has an excellent track record as a clinical leader.

I genuinely feel it’s only a matter of time before the giant supertanker which is the medical profession changes its bearings to acknowledge that sick people in their profession exist. Dr Phil Hammond has done a superb article on this.

I love my law school, BPP Law School. They got me through this. I have become a non executive director of their Students Association now. There’s a lot of work to be done there, but I am lucky that there are two colleagues there of mine who are simply the best: Shahban Aziz and Shaun Dias.

I am now about to be regulated by two professions. I could not be happier.

Thanks for your support. I couldn’t have done it without you.

Being restored to the GMC Medical Register has been a massive dream come true

I spent nine years at medical school, and about very few as a junior doctor.

I’ve now been in recovery for just over seven years.

But in that time I do remember doing shifts starting at Friday morning and ending on Monday night. I remember the cardiac arrest bleep in Hammersmith at 4 am, and doing emergency catheters at 3 am in Norfolk.

I had an unusual background. I loved medical research at Cambridge. In fact, my discovery how to diagnose the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia is cited by the major international labs. It is in the current Oxford Textbook of Medicine.

Being ensnared by the General Medical Council in their investigation process devastated my father. He lated died in 2010. I remember kissing him goodbye in the Intensive Care Ward of the Royal Free, the same ward which had kept me alive for six weeks in 2007.

I of course am completely overwhelmed by those events widely reported, especially in the one in 2004. The newspapers never report I was blind drunk. The media when they do not mention my alcohol dependence syndrome are missing out a key component of the jigsaw.

Until I die, I will never be safe with one alcoholic drink. I will go on a spiral of drinking, and that one event I am certain would either see me in a police cell or in A&E.

One event did change my life. I was blue lighted in, after a year of heavy drinking after I was erased by the GMC in 2006, having had a life-threatening epileptic fit. The crash team attempted emergency intubation, but I ended up having a cardiac arrest which was successfully resuscitated.

I do not wish to enter any blame games about what happened a decade ago. It turns out that the Trust which reported me as dishevelled and alcoholic, and having poor performance simultaneously, is in the Daily Mail this morning for a running a ‘chaotic’ A&E department.

It also turns out that another Trust in London which reported me as dishevelled and alcoholic, and having poor performance simultaneously, had its A&E department shut down this week.

I was in denial and had no insight. Hindsight is a wonderful thing, but I needed sick leave and a period of absence and support. But I do not wish to blame anyway for those events I wish had never happened some time ago.

But the GMC referrals were absolutely correct. I had a proper medical plan put in place for me when I awoke from my coma. I followed religiously my own GP’s advice too.

I am now physically disabled, and have had no regular salaried job since 2005. But I am content. I live in a small flat with my mother in Primrose Hill. I regularly go out to cultural events. I maintain my interest in dementia, going to a fourth conference this year for Alzheimer’s Europe in October, where I have been chosen to give one of the research talks. It’s actually on an idea which David Nicholson inspired me over.

I’ve done four books on medicine, including one on living well with dementia. The Fitness to Practice panel in their judgment note my contribution there, which I am pleased about.

The Panel also crucially made the link in their judgment that my poor performance in conduct and competence coincided with my period of illness, the alcohol dependence syndrome, for which I am now under a psychiatrist.

I go to AA sometimes, and the weekly recovery support group at my local hospital. Being in contact with other people who are starting the same process of getting their life back continues to inspire me. I also attend the suspended doctors group for the Practitioner Health Programme, which helps me understand myself too.

I believe that there is no higher law than somebody’s health. I understand the pressures of why trainees preventing them from seeking help in the regulatory process.

But I do have an unusual perspective. First and foremost, I am a patient myself, and proud of it.

Secondly, I am regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority. I can become a trainee solicitor, if I want to be. I had a careful due diligence process in 2010, and I thank the legal profession for rehabilitating me.

Thirdly, I will now be regulated once again by the General Medical Council pending a successful identity check on October 7 2014. Having my application to be restored to the UK medical register is a massive honour for me. I caused a lot of hurt to others during my time with the medical profession last time, and this time I would like things to be different, and be of worth.

This, I hope, will mean a lot to my late father.

I am grateful to all the people at the Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service, and to the GMC prosecutor for presenting a fair case on behalf of the GMC who need to promote patient safety.

I am encouraged that the GMC’s new Chair, Prof Terence Stephenson, “gets” change for the better for the profession, and has an excellent track record as a clinical leader.

I love my law school, BPP Law School. They got me through this. I have become a non executive director of their Students Association now. There’s a lot of work to be done there, but I am lucky that there are two colleagues there of mine who are simply the best: Shahban Aziz and Shaun Dias.

I am now about to be regulated by two professions. I could not be happier.

Thanks for your support. I couldn’t have done it without you.

Out of sight, out of mind

Please note: This blogpost has been edited since the first publication, due to a factual inaccuracy of mine this morning where I stated the Tavistock Clinic was private.

It is not private. I do sincerely apologise for this mixup. It was an entirely accident error of mine.

I have also changed the word ‘aggressive treatments’ to ‘thorough interventions’ on the advice of two different people.

I am further posting Kate’s very helpful comment below the end of this article.

I am extremely grateful to Kate for her comment.

________________________________________________________________________________________

I have previously written openly about my personal experiences as a sick doctor and beyond (please see here). Thank you if you were one of the 2000 or views of that blogpost on that particular day.

In 2008, the Department of Health under the previous government funded a two year pilot to commission and provide a specialist, confidential, service, the Practitioner Health Programme (PHP).

The service was free to all doctors and dentists in London with:

- mental health or addiction concern (at any level of severity); and,

- physical health concern (where that concern was potentially impacting on the practitioner’ performance).

The PHP complemented existing NHS GP, occupational health and specialist services. It demonstrated the need for the service (over 500 patients have now been treated, many with complex problems) and how savings could be achieved through swift, safe return to work.

The 2009 Boorman review of the health of the NHS workforce reported that:

- the direct costs of ill-health in NHS staff are in the region of £1.7 billion p.a.;

- the agency staff bill for the NHS is around £1.45 billion p.a. (spending closely related to sickness absence and staff turnover); and 2,500 ill-health retirements (some possibly preventable) each year cost the NHS £150m p.a.

The Chief Executive of the General Medical Council, Niall Dickson, commenting on the PHP said:

“We know of the stress and anguish experienced by doctors who become sick and how this can affect their work. There is not enough good support at local level and the PHP programme has shown what can be done.”

It is now pretty widely felt that prevention and early intervention could save the NHS millions of pounds, and employers can achieve huge savings by supporting doctors and ensuring they remain fit to practise, whilst maintaining or improving quality. The potential savings for employers far outweigh the likely cost of establishing a nationwide service (estimated at around £6 million). There is therefore a real economic case, as well as averting tragedies in human lives training in the NHS.

If you’re a sick Doctor, ‘Good medical practice’, the GMC’s code of conduct, is triggered under domain 2 for quality and safety by the following clause.

In my own particular case, it is recorded in two detailed witness statements that I tried to discuss in detail the alcohol problem that was concerning me with two Consultant Physicians in London.

In neither case was I offered a programme of alcohol management. I confided in them personal details.

It is a real pity that I did take up an offer by a Consultant who recommended the Tavistock Clinic, as I erroneously thought it was private not public. Notwithstanding that, no offer of sick leave was made, but that is my fault for not having let the discussion get that far.

But I really don’t wish to play any ‘blame game’ – for example I failed in not being under a General Practitioner at the time, as I was at that stage absolutely petrified that that GP would have reported me to the GMC subjecting me to years of investigation. I had years of investigation anyway, but without the critical help I needed.

Being under a General Practitioner for a medical professional is a requirement of their Code of Conduct according to rule thirty.

I think many aspects of my dire situation reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of the medical profession thinking that if a sick Doctor is ‘aware’ of his problem he has full insight into the distress the problem is causing to friends, family and beyond.

I feel that, had my problem been aggressively dealt with earlier, the subsequent failures in my alcohol management would not have occurred (three years later).

My erasure for me was perceived by me as the ultimate personal failure for having been through a public hearing, treated still in the media as a “show trial”, and a personal failure for not having got clinically better. On a note of wider contrition, however, I have no objection to the issues I was found proven to this day, and I think the GMC ultimately made the correct sanction.

Media reports, despite public humiliation, distressing not just for me but my late father at the time, make no reference to my underlying medical problems. I was sectioned in May 2006 due to alcoholism. It’s as if the establishment wishes purposefully to airbrush doctors being sick.

I was distraught on my erasure, for having no solution to my mental health problems in sight. The regulatory process exacerbated my misery, with psychiatrists not being able to rule out at anxiety and depressive component while I was heavily drinking.

I know I was ‘aware’ of my problem with empty drunk bottles of red wine, but it doesn’t mean that I had the motivation to take time off work then to do something about it.

Likewise, the GMC code (see clause twenty eight above) assumes that the sick Doctor has full insight.

In my case, it had a very unpleasant end.

Not just this, days before my 33rd birthday,

but this six week coma and two month neurorehabilitation (the full discharge diagnosis from a place where I used to be a junior clinical physician once with no health problems.)

I think it is incredibly hard for anyone to understand outside of the system how you get raped of your dignity and integrity by the regulator when you fail to improve from mental illness. And often this mental illness is exacerbated by the regulatory process, as 86 deaths of Doctors awaiting Fitness to Practice during the same period of my investigation might appear to testify.

As I never had a performance assessment or clinical supervisor during my regulatory process, despite four different consultants concluding I had a severe alcohol problem at least between August 2004 and spring 2005, I feel I was put into managed decline long before the final hearing in July 2006.

I think personally the system for sick doctors undergoing the regulatory process from the General Medical Council could be much better, but that might be just be an unfortunate personal experience: ‘there’s nothing to see here’.

But a good first management step for me would be to roll out the Practitioner Health Programme to a jurisdiction wider than London. Lives truly depend on it, and the general public deserve better from seniors in the medical profession. This, for me, is absolutely necessary to maintain trust in the medical profession, domain 4 of the current GMC Code of Conduct. The GMC need to make the dealings open in this regard, fundamentally.

As far as the Consultants who contributed to my 2006 erasure were concerned, I have been out of sight and out of mind. In fact, I haven’t spoken to them for a decade and needless to say they have not wished to contact me.

I may be newly physically disabled following 2007.

I don’t personally wish the GMC any ill will. I believe in rehabilitation being a regulated student member of the law profession now – but do they?

I am back now.

Kate’s really helpful comment:

The Med Net service IS FREE and confidential.

When medical trainees encounter difficulties, college tutors, clinical tutors, programme directors and educational supervisors are encouraged to signpost them to Med Net. It was very positive that the consultant, who was not your educational supervisor, took sufficient pastoral interest in your welfare to give you the Med Net contact details. Ultimately, it is down to junior doctors to contact the service. Had you sought an appointment with your trusts OH team, they’d have given you the same contact details. It would have still been down to you to make contact. (< Indeed. Thanks , noted )

Alcohol-related disorders are outside the Mental Health Act, so it is impossible to compel people to undergo “treatment”. “Treatment” is an unfortunate term, as there is little that therapists can do until an individual wants help or becomes so incapacitated that they cease using. Even then, the notion of “treatment” as something that is done “to” people is inappropriate. This is one of the reasons why addictive disorders are outwith the MHA. Compulsion doesn’t work. “Aggressive treatment” is a particularly unhelpful concept more appropriate for the treatment of leukaemia rather than substance misuse disorders. Intense cycles of chemo-irradiation may induce remission in oncology, but intense input achieves nothing in addiction.

Kate then said it was a pity that I did not take up the offer of that Consultant, which I absolutely agree with.

I can see why some Doctors would be driven to suicide. I was mentally ill, and felt the same with the GMC FTP.

At least 96 doctors have died while facing a fitness-to-practise investigation from the General Medical Council since 2004, though it is not clear how many of these cases were suicide.

I can understand exactly how this has happened.

I had a prolonged GMC investigation between 2004 and 2006. At no point during this process was I told when then this mentally arduous process would come to an end.

I think now, seven years into recovery, that there by the grace of God go I.

The media have a remarkably high level of detail of understanding from the perspective of the General Medical Council about forthcoming cases. It is impossible for the Doctor to get his side across in the media.

The GMC claim they don’t do show trials.

But my father was fully humiliated with the media storm.

My father was faced with a Doctor son who was in denial and lacked insight. My father is now dead, but I should like to say he probably died in complete humiliation of his son.

My experience is of a GMC which plays to people’s weaknesses in low self esteem and low confidence, a personality trait shared by many with addiction disorders.

Not one report in the mainstream media reported that I was severely alcoholic. And yet the GMC, prior to their erasure of me, erased me with five independent reports stating clearly that I had at least a severe alcohol problem; and that I needed help.

One of the referrals to the GMC was when I attended the A&E of a hospital with acute intoxication. In addition to the referral to the GMC by the Consultant in A&E, I was not offered any post-event support for alcoholism.

The GMC know how to present themselves in the media, but this is in contradistinction to the experience of those who have experienced the Fitness to Practise process first hand.

Dr Peter Wilmhurst writes in 2006 in a wide-ranging criticism of the GMC as follows:

In wishing to infer ‘bad character’, the General Medical Council must not go beyond its statutory duty of promoting public safety. Otherwise, there is simply mission creep and a torrent of smears into a hate campaign by the regulator or its company.

In 2005, one year before I was eventually due to see the GMC, I was suspended. This was due to an alcoholic bender in Northwick Park. I was crying all day in a pub because I could not cope with the investigation any more.

I had waved goodbye to my late father, and lied to him saying I was going shopping.

I didn’t. I ended up being sectioned by a psychiatric hospital in North London, and my father spent ages talking to the medical staff there.

I was then suspended. It was at that point, I wished to call it a day.

I phoned the Samaritans, and they talked me out of it.

I have never told anyone this story. I feel very strongly about what the General Medical Council did to me, even though it might have been merely a product of their inefficiency.

Nobody appears to wish to want to change the system. I’m pretty sure that there are juniors who wish to hold tight until they are Consultants.

What happened to me is that I had consultants in two Trusts in West and North London who said I was ‘late for work’, ‘smelling of alcohol’ and ‘dishevelled’.

None of this got reported in the main media.

I was erased. To this day, I still have no idea who retrospectively complained in graphic detail about my alcoholism did not offer me sick leave, or help with occupational health.

One of them even had the gall to write in his witness statement for the GMC that he gave me the phone number of a private clinic.

I find this particularly ironic as I was later done for incompetence, when that North London trust had allowed me to finish my medical job there, successfully running cardiac arrests there. I passed my Advanced Life Certificate there. I even have the certificate to prove it.

I feel disgusted by the way that the General Medical Council goes about its business.

Far too many one-sided media reports appear in the media containing detailed accounts, as yet unproven. There’s a sense of being hung before you even go to the gibbet.

I am now in my seventh year in recovery. I have done four books, and my Bachelor of Law, Master of Law and Master of Business Administration.

I even completed my pre-solicitor training, as I am regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority.

My late father died two months before the Solicitors Regulation Authority gave me permission to finish my legal training, after a meticulous consideration of various factors including details of my erasure.

I am now applying to be restored. And so everything gets racheted up again. The dogs will get unleashed.

And so far they’ve dragged me up to the City where I was struck off, without my late father, surrounded by the same bars and clubs and restaurants. I didn’t have a relapse. Care and compassion are simply two words which are not in the GMC’s dictionary.

I am even applying to go to a desk, non “facing job”. I am now following my erasure newly disabled, so I would not wish to do clinical medicine in any form.

I do not want to be in public health with the stigma of having been erased, for a period of life when I was very ill, and the undoubted discrimination that that would entail.

I had one year of sitting in a pub all day after I was eventually erased in 2006.

This was an extremely dangerous part of life. For my father, it was unbelievably distressing. Nonetheless, he came to visit me every day on the ITU when I was in a coma due to this a year later.

I so understand why there have been so many deaths of Doctors waiting GMC FTP. That could easily have been me.

But I am fighting fit now, and looking forward to my hearing very much.

My own medical career may be over, but the GMC must reform their procedures for sick doctors. Lives depend on it.

One of the ways that the General Medical Council will try to pin you down is if you appear blasé in any sense about your own behaviour, or lack insight into its repercussions.

I have a psychiatrist in West London who oversees my recovery. I am a barn door alcoholic now in recovery. One of the wisest things he has ever said to me is that it is impossible to ignore the distress I caused to friends, family and others. I think about this every day of my life in fact. It has left an indelible trace on Google, which I do not wish to forget. That’s why I have never asked for it to be removed.

I get upset that the BBC considers my tragic case of erasure from the Medical Register as ‘entertainment’. Behind this titillating story was someone who was in massive distress, and to some extent continues to be in distress.

I have learnt the General Medical Council (GMC) is only doing its job. Reports, like the latest damning one by Civitas on how the GMC treats sick doctors badly, come and go. And nothing really changes.

But I remember all too well what happened to me. I repeat that I find my behaviour then, as a different person, disgusting and unacceptable. But things came to a head when I was blue-lighted in at the beginning of June 2007 with an asystolic cardiac arrest which I was very lucky to be resuscitated out of. I then spent six weeks in a coma. I was fighting for my life, with drips, a central line, and the full army of Intensive Care machinery. The Consultant at the Royal Free warned people I was not expected to leave the hospital. I was clearly a very sick man.

My late father came to visit every day when I was learning how to walk and talk again at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery. That’s where I had spent six happy months, while healthy, learning about general neurology and dementia. It’s where I developed a lifelong interest in neurodegenerative disease, which pervades through my post-doctoral fellowship at the Institute of Neurology thereafter, my mention in the Oxford Textbook of Medicine, and my own book on wellbeing in dementia.

I am happy now that, having learnt how to walk and talk, I was invited to the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference in Copenhagen last month, and I went to the Alzheimer’s Show in Manchester and London this year. My friends include people living with dementia, and they tell me what’s important in policy now.

I remember though the days of having to hide my name on blogposts or my Twitter account. I remember how I was frightened to show myself in public in the last few years. I remember how my circle of friends completely collapsed, though I am happy with the very small number of very close friends I have now. I still continue to get trolled, like no tomorrow, with words like “Disgusting” and “How do you live with yourself?”

I do also remember how the General Medical Council took years with their investigations. I remember the torrent of newspaper articles explaining how likely it would be I would be struck off. I remember thinking how this was an inglorious end to my ten years training to be a Doctor, a profession which I still feel honoured to have been in once.

But the General Medical Council protracts out their investigations. The GMC never got round to appointing a clinical supervisor (very odd) even though my independent clinical examiners had concluded that I had a severe alcohol problem. So it rumbled on for a few years with my mental health in free fall. Dynamite.

This is extremely risky – dangerous – for the sick doctor. If you lack insight or if you’re in denial you can be finished (as indeed the numbers of people reported to have committed suicide while waiting for their Fitness to Practise sessions show).

I remember how I totally ‘lost it’ in 2005 a year before my final hearing. I had long left a medical job, but I just fell apart while still waiting for my GMC hearing. I went on a massive bender sat alone sobbing into my drink in a pub in Notting Hill very close to Portabello Road, ended up being sectioned, and then was suspended by the GMC.

A year after I was erased, with no job and no family or friends virtually, my life really did take a nosedive. I sat in pubs all day from opening time to closing time. I was done for drunk and disorder offences.

But I woke up after a six week coma, newly disabled, but with a new purpose. I did three books on postgraduate medicine, and I became regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority. I have three degrees, my Bachelor of Law, my Master of Law, and my Master of Business Administration, as well as my pre-solicitor training.

I didn’t get very far when I bothered going up to Manchester for my restoration application. The GMC hadn’t bothered to do a basic conflicts session, so the meeting was adjourned after one day. My friend Martin Rathfelder made it to support me. He like Jos Bell and Kate Swaffer are true friends.

It’s a miracle that I didn’t have a relapse being in the City where I had been with my late father, where I was erased, with plenty of bars and restaurants, with plenty of memories. It’s like you’re being set up to fail by the GMC – or else they are incredibly incompetent when it comes to dealing with people with mental health issues.

But I did get as far as asking the panel if I could hold the hearing in public this time. I want to explain to the whole world why and how alcohol destroyed my life, and caused distress to others.

I think the GMC did the right thing in getting rid of me from the medical profession, but I am still bemused why one consultant in West London asked me to sort it out by giving me a phone number of the Priory, did not refer me to Occupational Health, and did not offer me sick leave. I am bemused why various consultants described me as looking dishevelled and alcoholic, and yet allowed me to finish my medical jobs in London, without referring me to Occupational Health. I even ran a number of cardiac arrests successfully, while being allowed to finish that job where the consultants complained some years later, because I had obtained my Advanced Life Support qualification. The practical thing to do would have been to refer me, give me sick leave, assess me, and get me back to work, if conceivably possibly. The alternative was a vindictive complaint, albeit a correct one, years after the event.

By the time I was erased, the GMC had been given five reports from five independent doctors stating clearly that my primary problem was a severe alcoholic dependence disorder, and that I desperately needed help.

I never received this help until the NHS saved my life a year later.

The GMC will wish to ‘win their case’ and I strictly speaking am not allowed to bring any of this up in case it reaks of bitterness.

The GMC opposed my application to explain all this and my recovery in public. The panel rejected the GMC’s case.

In my view, Clare Gerada’s “Practitioner Health Programme” is a necessary lifeline for those are sick Doctors, and who fall under the London jurisdiction.

Prof Gerada is a true inspirational NHS leader.

Needless to say, I’ve never had an alcoholic drink for more than seven years, since my coma. I’m one of those guys who has no off switch after one drink, such that I’ll either end up in A&E or in a police cell.

My case will now be held in Manchester beginning August 20th 2014. If you want to begin to understand how sick doctors cope, or do not cope, please feel to come along.

Toxic cultures, NHS Trusts and the Francis Report.

Robert Francis has an incredibly difficult task. It is difficult for people who have not qualified in medicine, even managers and leaders of healthcare think tanks, to understand how this situation has arisen. Being a senior lawyer, his approach will necessarily involve “the law is not enough”. The NHS is currently a “political football”, but the overriding objective must be one of patient safety. Whatever your views about managers following financial targets religiously, and regulatory authorities pursuing their own targets sometimes with equal passion, it is hard to escape from the desire for a national framework for patient safety. This is at a time indeed when it is proposed that the National Health and Patient Safety Agency should be abolished, which indeed has oversight of medical devices and equipment. Indeed, one of the findings of the Francis Inquiry is that essential medical equipment was not always available or working. A general problem with the approach of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) has been the abolition of ‘national’ elements, such as abolition of the Health Protection Authority.

That the hospital assumes voluntarily a duty-of-care for its patient once the patient presents himself is a given in English law, but this fact is essential to establish that there has been a breach of duty-of-care legally later down the line. In the increasingly corporate nature of the NHS following the Health and Social Care Act, there is of course a mild irony that there is more than a stench of corporate scandals in the aftermath which is about to explode in English healthcare. Patients’ families feel that they have been failed, and this is a disgrace.

ENRON was a corporate scandal of equally monumental proportions, as explained here:

Mid Staffs NHS Foundation Trust was poor at identifying when things went wrong and managing risk. Some serious errors happened more than once and the trust had high levels of complaints compared with other trusts.

The starting point must be whether the current law is good enough. We have systems in place where complaints can be made against doctors, nurses, midwives and hospitals through the GMC, MWC and CQC respectively, further to local resolution. In fact, it is still noteworthy that many junior and senior doctors are not that cognisant of the local and national complaint mechanisms at all, and the mechanisms used for risk mitigation. There is a sense that the existing regulatory framework is failing patients, and public trust and confidence in medical and nursing, and this might be related to Prof Jarman’s suggestion of an imbalance between clinicians and managers in the NHS.

The Francis Inquiry heard a cornucopia of evidence about a diverse range of clinical patient safety issues, and indeed where early warnings were made but ignored. Prof Brian Jarman incredibly managed to encapsulate many of the single issues in a single tweet this morning:

Any list of failings makes grim reading. There are clear management failures. For example, assessing the priority of care for patients in accident and emergency (A&E) was routinely conducted by unqualified receptionists. There was often no experienced surgeon in the hospital after 9pm, with one recently qualified doctor responsible for covering all surgical patients and admitting up to 20 patients a night. A follower on my own Twitter thread who is in fact him/herself a junior, stated this morning to me that this problem had not gone away:

However, it is unclear what there may be about NHS culture where clinicians do not feel they are able to “whistle blow” about concerns. The “culture of fear” has been described previously, and was alive-and-well on my Twitter this morning:

Experience from other sectors and other jurisdictions is that the law clearly may not be protective towards employees who have genuine concerns which are in the “public interest”, and whose concerns are thereby suppressed in a “culture of bullying“. This breach of freedom of expression is indeed unlawful as a breach of human rights, and toxic leaders in other sectors are able to get away with this, in meeting their targets (in the case of ENRON increased profitability), “project a vision”, and exhibit “actions that “intimidate, demoralize (sic), demean and marginalize (sic)” others. Typically, employees are characterised as being of a vulnerable nature, and you can see how the NHS would be a great place for a toxic culture to thrive, as junior doctors and nurses are concerned about their appraisals and assessments for personal career success. “Projecting a vision” for a toxic hospital manager might mean performing well on efficiency targets, which of course might be the mandate of the government at the time, even if patient safety goes down the pan. Managers simply move onto a different job, and often do not have to deal even with the reputational damage of their decisions. Efficiency savings of course might be secured by “job cuts” (another follower):

Another issue which is clearly that such few patients were given the drug warfarin to help prevent blood clots despite deep vein thrombosis being a major cause of death in patients following surgery. This is a fault in decision-making of doctors and nurses, as the early and late complications of any surgery are pass/fail topics of final professional exams. Another professional failing in regulation of the nurses is that nurses lacked training, including in some cases how to read cardiac monitors, which were sometimes turned off, or how to use intravenous pumps. This meant patients did not always get the correct medication. The extent to which managers ignored this issue is suggestive of wilful blindness. A collusion in failure between management and surgical teams is the finding that delays in operations were commonplace, especially for trauma patients at weekends; surgery might be delayed for four days in a row during which time patients would receive “nil by mouth” for most of the day.

Whether this toxic culture was isolated and unique to Mid Staffs, akin to how corporate failures were rather specialist in ENRON, is a question of importance. What is clear that there has been a fundamental mismatch between the status and perception of healthcare entities where certain individuals have “gamed” the situation. Alarmingly it has also been reported that the University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust have also had a spate of failures in in maternity, A&E and general medical services. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act (2002) was enacted in the US in response to a number of high-profile accounting scandals. In English law, the Financial Markets and Services Act (2010), even during Labour’s “failure of regulation” was drafted to fill a void in financial regulation. There is now a clear drive for someone to take control, in a manner of crisis leadership in response to natural disasters. Any lack of leadership, including an ability to diagnose the crisis at hand and respond in a timely and appropriate fashion, against the backdrop of a £2bn reorganisation of the NHS, are likely to constitute “barriers-to-improvement” in the NHS.

This issue is far too important for the NHS to become a case for privatisation. It is a test of the mettle of politicians to be able to cope with this. They may have to legislate on this issue, but David Cameron has shown that he is resistant to legislate even after equally lengthy reports (such as the Leveson Inquiry). It is likely that a National Patient Safety Act which puts on a statutory footing a statutory duty for all patients treated in the NHS, even if they are seen by private contractors using the NHS logo, may be entitled to a formal statutory footing. The footing could be to avoid “failure” where “failure” is avoiding harm (non-maleficence). Company lawyers will note the irony of this being analogous to s.172 Companies Act (2006) obliging company directors to promote the “success” of a company, where “success” is defined in a limited way in improving shareholder dividend and profitability under existing common law.

The law needs to restore public trust and confidence in the nursing and healthcare professions, and the management upon which they depend. The problem is that the GMC and other regulatory bodies have limited sanctions, and the law has a limited repertoir including clinical negligence and corporate manslaughter with limited scope. At the end of the day, however, this is not a question about politics or the legal and medical professions, it is very much about real people.

The advantage of putting this on the statute books once-and-for-all is that it would send out a powerful signal that actions of clinical and management that meet targets but fail in patient safety have imposable sanctions. After America’s most high-profile corporate fraud trial, Mr Lay, the ENRON former chief executive was found guilty on 25 May on all six fraud and conspiracy charges that he faced. Many relatives and patients feel that what happened at Stafford was much worse as it affected real people rather than £££. However, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act made auditors culpable, and the actions of managers are no less important.

This is not actually about Jeremy Hunt. Warning: this is about to get very messy. That Mid Staffs is not isolated strongly suggests that an ability of managers and leaders in Trusts to game the system while failing significantly in patient safety, and the national policy which produced this merits attention, meaning also that urgent legislation is necessary to stem these foci of toxicity. A possible conclusion, but presumption of innocence is vital in English law, from Robert Francis, and he is indeed an eminent QC in regulatory law, is that certain managers were complicit in clinical negligence at their Trusts to improve managerial ratings, having rock bottom regard for actual clinical safety. This represents a form of wilful blindness (and Francis as an eminent regulatory QC may make that crucial link), and there is an element of denial and lack of insight by the clinical regulatory authorities in dealing with this issue, if at all, promptly to secure trust from relatives in the medical profession. The legal profession has a chance now to remedy that, but only if the legislature enable this. But this will be difficult.

We've been here before. On legislation against toxic culture within the NHS: lessons from ENRON for the Francis Report.

Robert Francis has an incredibly difficult task. It is difficult for people who have not qualified in medicine, even managers and leaders of healthcare think tanks, to understand how this situation has arisen. Being a senior lawyer, his approach will necessarily involve “the law is not enough”. The NHS is currently a “political football”, but the overriding objective must be one of patient safety. Whatever your views about managers following financial targets religiously, and regulatory authorities pursuing their own targets sometimes with equal passion, it is hard to escape from the desire for a national framework for patient safety. This is at a time indeed when it is proposed that the National Health and Patient Safety Agency should be abolished, which indeed has oversight of medical devices and equipment. Indeed, one of the findings of the Francis Inquiry is that essential medical equipment was not always available or working. A general problem with the approach of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) has been the abolition of ‘national’ elements, such as abolition of the Health Protection Authority.

That the hospital assumes voluntarily a duty-of-care for its patient once the patient presents himself is a given in English law, but this fact is essential to establish that there has been a breach of duty-of-care legally later down the line. In the increasingly corporate nature of the NHS following the Health and Social Care Act, there is of course a mild irony that there is more than a stench of corporate scandals in the aftermath which is about to explode in English healthcare. Patients’ families feel that they have been failed, and this is a disgrace.

ENRON was a corporate scandal of equally monumental proportions, as explained here:

Mid Staffs NHS Foundation Trust was poor at identifying when things went wrong and managing risk. Some serious errors happened more than once and the trust had high levels of complaints compared with other trusts.

The starting point must be whether the current law is good enough. We have systems in place where complaints can be made against doctors, nurses, midwives and hospitals through the GMC, MWC and CQC respectively, further to local resolution. In fact, it is still noteworthy that many junior and senior doctors are not that cognisant of the local and national complaint mechanisms at all, and the mechanisms used for risk mitigation. There is a sense that the existing regulatory framework is failing patients, and public trust and confidence in medical and nursing, and this might be related to Prof Jarman’s suggestion of an imbalance between clinicians and managers in the NHS.

The Francis Inquiry heard a cornucopia of evidence about a diverse range of clinical patient safety issues, and indeed where early warnings were made but ignored. Prof Brian Jarman incredibly managed to encapsulate many of the single issues in a single tweet this morning:

Any list of failings makes grim reading. There are clear management failures. For example, assessing the priority of care for patients in accident and emergency (A&E) was routinely conducted by unqualified receptionists. There was often no experienced surgeon in the hospital after 9pm, with one recently qualified doctor responsible for covering all surgical patients and admitting up to 20 patients a night. A follower on my own Twitter thread who is in fact him/herself a junior, stated this morning to me that this problem had not gone away:

However, it is unclear what there may be about NHS culture where clinicians do not feel they are able to “whistle blow” about concerns. The “culture of fear” has been described previously, and was alive-and-well on my Twitter this morning:

Experience from other sectors and other jurisdictions is that the law clearly may not be protective towards employees who have genuine concerns which are in the “public interest”, and whose concerns are thereby suppressed in a “culture of bullying“. This breach of freedom of expression is indeed unlawful as a breach of human rights, and toxic leaders in other sectors are able to get away with this, in meeting their targets (in the case of ENRON increased profitability), “project a vision”, and exhibit “actions that “intimidate, demoralize (sic), demean and marginalize (sic)” others. Typically, employees are characterised as being of a vulnerable nature, and you can see how the NHS would be a great place for a toxic culture to thrive, as junior doctors and nurses are concerned about their appraisals and assessments for personal career success. “Projecting a vision” for a toxic hospital manager might mean performing well on efficiency targets, which of course might be the mandate of the government at the time, even if patient safety goes down the pan. Managers simply move onto a different job, and often do not have to deal even with the reputational damage of their decisions. Efficiency savings of course might be secured by “job cuts” (another follower):

Another issue which is clearly that such few patients were given the drug warfarin to help prevent blood clots despite deep vein thrombosis being a major cause of death in patients following surgery. This is a fault in decision-making of doctors and nurses, as the early and late complications of any surgery are pass/fail topics of final professional exams. Another professional failing in regulation of the nurses is that nurses lacked training, including in some cases how to read cardiac monitors, which were sometimes turned off, or how to use intravenous pumps. This meant patients did not always get the correct medication. The extent to which managers ignored this issue is suggestive of wilful blindness. A collusion in failure between management and surgical teams is the finding that delays in operations were commonplace, especially for trauma patients at weekends; surgery might be delayed for four days in a row during which time patients would receive “nil by mouth” for most of the day.

Whether this toxic culture was isolated and unique to Mid Staffs, akin to how corporate failures were rather specialist in ENRON, is a question of importance. What is clear that there has been a fundamental mismatch between the status and perception of healthcare entities where certain individuals have “gamed” the situation. Alarmingly it has also been reported that the University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust have also had a spate of failures in in maternity, A&E and general medical services. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act (2002) was enacted in the US in response to a number of high-profile accounting scandals. In English law, the Financial Markets and Services Act (2010), even during Labour’s “failure of regulation” was drafted to fill a void in financial regulation. There is now a clear drive for someone to take control, in a manner of crisis leadership in response to natural disasters. Any lack of leadership, including an ability to diagnose the crisis at hand and respond in a timely and appropriate fashion, against the backdrop of a £2bn reorganisation of the NHS, are likely to constitute “barriers-to-improvement” in the NHS.

This issue is far too important for the NHS to become a case for privatisation. It is a test of the mettle of politicians to be able to cope with this. They may have to legislate on this issue, but David Cameron has shown that he is resistant to legislate even after equally lengthy reports (such as the Leveson Inquiry). It is likely that a National Patient Safety Act which puts on a statutory footing a statutory duty for all patients treated in the NHS, even if they are seen by private contractors using the NHS logo, may be entitled to a formal statutory footing. The footing could be to avoid “failure” where “failure” is avoiding harm (non-maleficence). Company lawyers will note the irony of this being analogous to s.172 Companies Act (2006) obliging company directors to promote the “success” of a company, where “success” is defined in a limited way in improving shareholder dividend and profitability under existing common law.

The law needs to restore public trust and confidence in the nursing and healthcare professions, and the management upon which they depend. The problem is that the GMC and other regulatory bodies have limited sanctions, and the law has a limited repertoir including clinical negligence and corporate manslaughter with limited scope. At the end of the day, however, this is not a question about politics or the legal and medical professions, it is very much about real people.

The advantage of putting this on the statute books once-and-for-all is that it would send out a powerful signal that actions of clinical and management that meet targets but fail in patient safety have imposable sanctions. After America’s most high-profile corporate fraud trial, Mr Lay, the ENRON former chief executive was found guilty on 25 May on all six fraud and conspiracy charges that he faced. Many relatives and patients feel that what happened at Stafford was much worse as it affected real people rather than £££. However, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act made auditors culpable, and the actions of managers are no less important.