Home » Posts tagged 'ethics'

Tag Archives: ethics

The ubiquitous failure to 'regulate culture' speaks volumes

It is alleged that a problem with socialists is that, at the end of the day, they all eventually run out of somebody else’s money. Perhaps more validly, it might be proposed that the problem with all politicians is that they all run of other people to blame?

It is almost as if politicians form in their minds a checklist of people they wish to nark off systematically when they get into government: candidates might include lawyers, Doctors, bankers, nurses, disabled citizens, to name but a few.

Politicians are able to use the law as a weapon. That’s because they write it. The law progressively has been reluctant to decide on moral or ethical issues, but altercations have occurred over potentially inflammable issues such as ‘the bedroom tax’. Normative ethics takes on a more practical task, which is to arrive at moral standards that regulate right and wrong conduct.

There has always been a tension between the law and ethics. As an example, to prove an offence in the English criminal law, you have to prove beyond reasonable doubt an intention rather than a motive, for example that a person intended to burn someone’s house down, rather than why he had intended so. Normative ethics involve articulating the good habits that we should acquire, the duties that we should follow, or the consequences of our behaviour on others. The ultimate ‘normative principle’ is that we should do to others what we would want others to do to us.

Parliament is about to get its knickers in a twist once again over the thorny issue of press regulation. However, there is a sense of history repeating itself. A few centuries ago, “Areopagitica” was published on 23 November 1644, at the height of the English Civil War. It is titled after Areopagitikos (Greek: ?????????????), a speech written by the Athenian orator Isocrates in the 5th century BC. (The Areopagus is a hill in Athens, the site of real and legendary tribunals, and was the name of a council whose power Isocrates hoped to restore).

“Areopagitica” was distributed via pamphlet, defying the same publication censorship it argued vehemently against. As a Protestant, Milton had supported the Presbyterians in Parliament, but in this work he argued forcefully against the Licensing Order of 1643, in which Parliament required authors to have a license approved by the government before their work could be published.

Milton then argued that Parliament’s licensing order will fail in its purpose to suppress scandalous, seditious, and libellous books: “This order of licensing conduces nothing to the end for which it was framed.” Milton objects, arguing that the licensing order is too sweeping, because even the Bible itself had been historically limited to readers for containing offensive descriptions of blasphemy and wicked men.

England has for a long time experienced problems with moving goalposts in the law, and indeed the judicial solutions sought have varied with the questions being asked. Lord Justice Leveson acknowledged that the “world wide web” was a medium subject to no central authority and that British websites were competing against foreign news organisations, particularly in America, which were part of no regulatory system.

Leveson once nevertheless proposed that newspapers should still face more regulation than the internet because parents can ‘to some extent’ control what their children see online, while they could not control what they see on a newsagent or supermarket shelf.

‘It is clear that the enforcement of law and regulation online is problematic,’ said Lord Justice Leveson at the end of his year-long inquiry into press ethics.

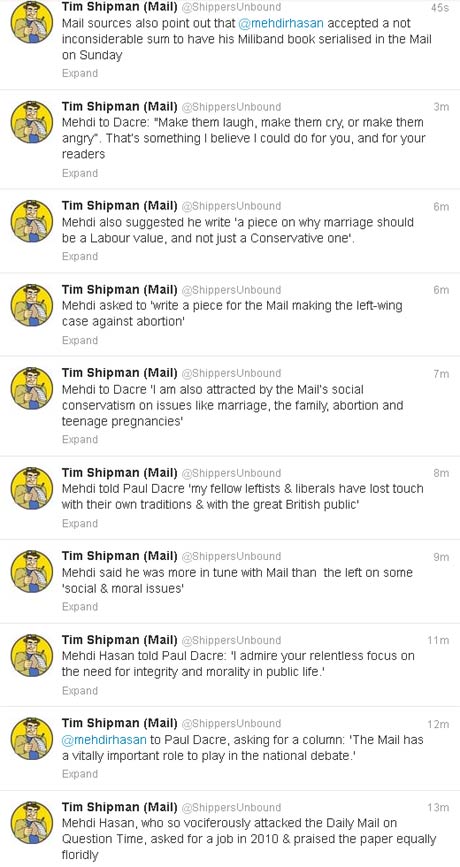

An attempt at ‘regulating culture’ was dismissed in the Leveson Report largely through arguing that the offences were substantially already ‘covered’, such as trespass of the person or phone hacking. And yet it is the case that there are ‘victims of phone hacking’ who feel that we are unlikely to be much further forward than we were before spending millions on an investigation into journalistic practices. In recent discussions this week, eyebrows have been raised at the suggestion that Ed Miliband could write to senior members in the Mail-on-Sunday empire to suggest that the culture in their newspapers is awry, and to ask them to do something about it. It could be argued it is none of Miliband’s business, except that Miliband would probably prefer the Mail to write favourably about him. Such flexibility in judgments might be on a par with Mehdi Hasan changing his writing style and target audience within a few years, as the recent Twitterstorm demonstrates.

The medical and nursing professions have latterly urged for an approach which is not overzealously punitive. There have been very few sanctions for regulatory offences in Mid Staffs or Morecambe Bay, for example.

Robert Francis QC still identified that an institutional culture which put the “business of the system ahead of patients” is to blame for the failings surrounding Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust. Announcing the publication of his three volume report into the Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust public inquiry, Mr Francis described what happened as a “total system failure”.

Francis argued the NHS culture during the 2005-2009 period considered by the inquiry as one that “too often didn’t consider properly the impact on patients of decisions”. However, he said the problems could not “be cured by finding scapegoats or [through] reorganisation” of the NHS but by a “real change in culture”. However, having identified the problem, solutions for cultural ‘failure’ in the NHS have not particularly been forthcoming.

There are promising reports of ‘cultural change’ in the NHS, for example at Mid Staffs and Salford, but some aggrieved relatives of patients still have a feeling that ‘justice has not been done’. There has been no magic bullet from the legislature over concerns about bad practice in the NHS, and it is unlikely that any are immediately forthcoming. There is little doubt, however, that parliament improving the law on safe staffing or how whistleblowers can raise issues in the public interest safely might be constructive steps forward. There therefore exists how the law might conceivably ‘improve’ the culture, and one suspects that this change in culture will have to permeate throughout the entire organisation to be effective. That is, fundamentally, people are not punished for speaking out safely, and, whilst legitimate employers’ interests will have to be protected, the protection for employees will have to be necessary and proportionate equally under such a framework.

Journalism and the NHS are not isolated examples, however, Newly released reports into the failures of management at several major banks – HBOS, Barclays, and JP Morgan among them – show that some of the worst losses had roots deeper than the 2008 credit crisis. It is said that a toxic internal culture and poor management, not the subprime mortgage collapse, caused billion-dollar losses at some of the world’s largest banks

In an argument akin to that used to argue that there is no need to regulate the journalism industry, the banking industry have long maintained that a strong feeling of internal competition can be healthy for profitability, but problems such as abject fraud and misselling of financial products are already illegal.

The situation is therefore a nonsense one. There is a failed culture, ranging across several diverse disciplines, of politicians wishing to use regulation to correct failed cultures. Cultures of an organisation, even with the best will in the world, can only be changed from within, even if the public, vicariously through politicians, wish to impose moral and ethical standards from outside.

Whichever way you wish to frame the argument, it might appear ‘we cannot go on like this.’ It is a pathology which straddles across all the major political parties, and yet all the parties wish to claim that they have identified a poor culture.

Their lack of perception about what to do with these problems is perhaps further evidence that the political class is not fit for the job.

Isn’t it time to admit failure in ‘regulating cultures’?

It is alleged that a problem with socialists is that, at the end of the day, they all eventually run out of somebody else’s money. Perhaps more validly, it might be proposed that the problem with all politicians is that they all run of other people to blame?

It is almost as if politicians form in their minds a checklist of people they wish to nark off systematically when they get into government: candidates might include lawyers, Doctors, bankers, nurses, disabled citizens, to name but a few.

Politicians are able to use the law as a weapon. That’s because they write it. The law progressively has been reluctant to decide on moral or ethical issues, but altercations have occurred over potentially inflammable issues such as ‘the bedroom tax’. Normative ethics takes on a more practical task, which is to arrive at moral standards that regulate right and wrong conduct.

There has always been a tension between the law and ethics. As an example, to prove an offence in the English criminal law, you have to prove beyond reasonable doubt an intention rather than a motive, for example that a person intended to burn someone’s house down, rather than why he had intended so. Normative ethics involve articulating the good habits that we should acquire, the duties that we should follow, or the consequences of our behaviour on others. The ultimate ‘normative principle’ is that we should do to others what we would want others to do to us.

Parliament is about to get its knickers in a twist once again over the thorny issue of press regulation. However, there is a sense of history repeating itself. A few centuries ago, “Areopagitica” was published on 23 November 1644, at the height of the English Civil War. It is titled after Areopagitikos (Greek: ?????????????), a speech written by the Athenian orator Isocrates in the 5th century BC. (The Areopagus is a hill in Athens, the site of real and legendary tribunals, and was the name of a council whose power Isocrates hoped to restore).

“Areopagitica” was distributed via pamphlet, defying the same publication censorship it argued vehemently against. As a Protestant, Milton had supported the Presbyterians in Parliament, but in this work he argued forcefully against the Licensing Order of 1643, in which Parliament required authors to have a license approved by the government before their work could be published.

Milton then argued that Parliament’s licensing order will fail in its purpose to suppress scandalous, seditious, and libellous books: “This order of licensing conduces nothing to the end for which it was framed.” Milton objects, arguing that the licensing order is too sweeping, because even the Bible itself had been historically limited to readers for containing offensive descriptions of blasphemy and wicked men.

England has for a long time experienced problems with moving goalposts in the law, and indeed the judicial solutions sought have varied with the questions being asked. Lord Justice Leveson acknowledged that the “world wide web” was a medium subject to no central authority and that British websites were competing against foreign news organisations, particularly in America, which were part of no regulatory system.

Leveson once nevertheless proposed that newspapers should still face more regulation than the internet because parents can ‘to some extent’ control what their children see online, while they could not control what they see on a newsagent or supermarket shelf.

‘It is clear that the enforcement of law and regulation online is problematic,’ said Lord Justice Leveson at the end of his year-long inquiry into press ethics.

An attempt at ‘regulating culture’ was dismissed in the Leveson Report largely through arguing that the offences were substantially already ‘covered’, such as trespass of the person or phone hacking. And yet it is the case that there are ‘victims of phone hacking’ who feel that we are unlikely to be much further forward than we were before spending millions on an investigation into journalistic practices. In recent discussions this week, eyebrows have been raised at the suggestion that Ed Miliband could write to senior members in the Mail-on-Sunday empire to suggest that the culture in their newspapers is awry, and to ask them to do something about it. It could be argued it is none of Miliband’s business, except that Miliband would probably prefer the Mail to write favourably about him. Such flexibility in judgments might be on a par with Mehdi Hasan changing his writing style and target audience within a few years, as the recent Twitterstorm demonstrates.

The medical and nursing professions have latterly urged for an approach which is not overzealously punitive. There have been very few sanctions for regulatory offences in Mid Staffs or Morecambe Bay, for example.

Robert Francis QC still identified that an institutional culture which put the “business of the system ahead of patients” is to blame for the failings surrounding Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust. Announcing the publication of his three volume report into the Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust public inquiry, Mr Francis described what happened as a “total system failure”.

Francis argued the NHS culture during the 2005-2009 period considered by the inquiry as one that “too often didn’t consider properly the impact on patients of decisions”. However, he said the problems could not “be cured by finding scapegoats or [through] reorganisation” of the NHS but by a “real change in culture”. However, having identified the problem, solutions for cultural ‘failure’ in the NHS have not particularly been forthcoming.

There are promising reports of ‘cultural change’ in the NHS, for example at Mid Staffs and Salford, but some aggrieved relatives of patients still have a feeling that ‘justice has not been done’. There has been no magic bullet from the legislature over concerns about bad practice in the NHS, and it is unlikely that any are immediately forthcoming. There is little doubt, however, that parliament improving the law on safe staffing or how whistleblowers can raise issues in the public interest safely might be constructive steps forward. There therefore exists how the law might conceivably ‘improve’ the culture, and one suspects that this change in culture will have to permeate throughout the entire organisation to be effective. That is, fundamentally, people are not punished for speaking out safely, and, whilst legitimate employers’ interests will have to be protected, the protection for employees will have to be necessary and proportionate equally under such a framework.

Journalism and the NHS are not isolated examples, however, Newly released reports into the failures of management at several major banks – HBOS, Barclays, and JP Morgan among them – show that some of the worst losses had roots deeper than the 2008 credit crisis. It is said that a toxic internal culture and poor management, not the subprime mortgage collapse, caused billion-dollar losses at some of the world’s largest banks

In an argument akin to that used to argue that there is no need to regulate the journalism industry, the banking industry have long maintained that a strong feeling of internal competition can be healthy for profitability, but problems such as abject fraud and misselling of financial products are already illegal.

The situation is therefore a nonsense one. There is a failed culture, ranging across several diverse disciplines, of politicians wishing to use regulation to correct failed cultures. Cultures of an organisation, even with the best will in the world, can only be changed from within, even if the public, vicariously through politicians, wish to impose moral and ethical standards from outside.

Whichever way you wish to frame the argument, it might appear ‘we cannot go on like this.’ It is a pathology which straddles across all the major political parties, and yet all the parties wish to claim that they have identified a poor culture.

Their lack of perception about what to do with these problems is perhaps further evidence that the political class is not fit for the job.

Vince's speech at the LibDem conference: Many themes should be a top priority for us too

Vince’s speech, unlike the misreporting of it mainly from the BBC who patently didn’t understand the business or legal issues involved, made for very interesting reading for me as a Labour member with an interest in both business and commercial law. I would like to discuss various intriguing aspects of it for me.

But to hold our own we need to maintain our party’s identity and our authentic voice.

This is now being an increasingly difficult problem for the Liberal Democrats. There has to be by necessity an alignment of the beliefs and values of the leadership of the Party and its grassroot members. It was interesting to eavesdrop on the discussion that the Party had earlier this week on brand strategy, as it was clear from the floor that there is much confusion about the brand identity and brand equity of the members of the Party. Of course, the position on the rate of cuts which ultimately emerged from Vince Cable and Nick Clegg remains for many quite unfathomable, and certain issues are pretty straightforward by the Liberal Democrats, for example strong Liberal (anti-statist) values in civil liberties. However, certain grey areas see problems for the leadership and activists alike; for example, free schools is an incredibly perplexing area for the Liberal Democrats to embrace in a way so enthusiastically as Michael Gove’s fervour.

We will fight the next general elections as an independent force with our options open. Just like 2010. But coalition is the future of politics. It is good for government and good for Britain. We must make sure it is good for the Lib Dems as well.

Yes, indeed. It is now ‘do-or-die’ for the Liberal Democrats. There won’t be an end of ‘boom-and-bust’ in this context, unfortunately, because if the Liberal Democrats get the economic recovery and cuts wrong, even if the recession ends, they will be unelectable for a decade. However, it is argued that if the Liberal Democrats make a success of their new Coalition policy, the Coalition politics of pluralism could become accepted.

There was, of course, a global financial crisis. But our Labour predecessors left Britain exceptionally vulnerable and damaged: more personal debt than any other major economy; a dangerously inflated property bubble; and a bloated banking sector behaving as masters, not the servants of the people. Their economic model combined the financial lunacies of Ireland and Iceland. They built a house on sand and thought that they were ushering in a new, progressive work of architecture. It has collapsed. They lacked foresight; now they even lack hindsight.

If Cable feels Labour is in denial over the deficit, undeniably he has been slow to come to the conclusion that the crisis was global. I remember him pontificating in the Commons about how it was an academic philosophical issue of where the financial crisis came from, but it was necessary to find a solution for it. Vince Cable’s lack of acceptance that this was a global crisis historically speaks volumes.

We know that if elected Labour planned to raise VAT. They attack this government’s cuts but say not a peep about the £23bn of fiscal tightening Alistair Darling had already introduced. They planned to chop my department’s budget by 20 to 25%, but now they oppose every cut, ranting with synthetic rage, and refuse, point blank, to set out their alternatives. They demand a plan B but don’t have a plan A. The only tough choice they will face is which Miliband.

This statement is totally ridiculous. If Vince Cable is so self-effacing, can he not at least give a suitable explanation for this poster?

But I am not seeking retribution. We have a pressing practical problem: the lack of capital for sound, non property, business. Many firms say they are already being crippled by banks’ charges and restrictions.

This is undoubtedly a sensible line of attack for Vince and George to pursue, as it encompasses the Liberal

Democrats’ values of fairness, and Labour’s lack of engaging with the public about how the bankers, who had largely caused this crisis, were not been punished for their recklessness. If anything, it is perceived that Labour pumped lots of taxpayers’ money in it, whilst the leading CEOs in the investment banks received knighthoods and huge bonuses. Labour’s fundamental error, if there is to be one single one amongst the plethora, is the unforgiveable increase in the rich-poor divide, which will forever be a legacy of Labour. It began in earnest with Thatcher, progressed with Blair, and compounded through Gordon Brown’s long stint as Chancellor. This should be a top priority for Labour too.

And the principle of responsible ownership should apply across the business world. We need successful business. But let me be quite clear. The Government’s agenda is not one of laissez-faire. Markets are often irrational or rigged. So I am shining a harsh light into the murky world of corporate behaviour. Why should good companies be destroyed by short term investors looking for a speculative killing, while their accomplices in the City make fat fees? Why do directors sometimes forget their wider duties when a cheque is waved before them?

This is an incredibly important paragraph in my opinion, as short-termism has been identified by many academics in leadership, including William George at the Harvard Business School, as a major cause of irresponsible leadership in business. This, together with failures in corporate governance and corporate social responsibility in a post-Enron age, remain admirable targets for Vince’s wrath. This should be a top priority for Labour too.

??But the big long term question is: how does the country earn a living in future? Natural resources? The oil money was squandered. Metal bashing? Mostly gone to Asia. Banking? Been there, done that. What is left? Actually quite a lot. People. Skilled and educated people. High tech manufacturing of which we already have a great deal. Creative industries, IT and science based industries and professional services. In my job I meet many outstanding, world class, British based companies. But we need more companies and more jobs in the companies we have. It is my job as Business Secretary to support business growth. And this knowledge based economy requires more high quality people from FE, HE and vocational training. Here, we have a problem. Businesses cannot grow because of a shortage of trained workers while our schools churn out young people regarded by companies as virtually unemployable. The pool of unemployed graduates is growing while there is a chronic shortage of science graduates and especially engineers. There has to be a revolution in post 16 education and training. We are making a start. Despite cuts, my department is funding 50,000 extra high level apprenticeships this year – vital for a manufacturing revival. My Conservative colleague David Willetts and I want to sweep away the artificial barriers between universities and FE; between academic and vocational; between full time, part time and continuing life long learning; between the academic and vocational.

The ‘Yeah, but’ is that Vince Cable is making savage cuts in universities such as Cambridge, currently top in the world, at a time when we should be investing in basic research, translationary research and applied research, with a view to investing in our country’s future. This should be a top priority for Labour too.