Home » Posts tagged 'dementia' (Page 2)

Tag Archives: dementia

Design in dementia : a blog viewpoint by Dr Shibley Rahman

This week, I attended a superb symposium on design principles in dementia care. Whilst I may have been in the land of the Trustefarians (those borne into trust funds), actually I was in a comfortable room in a community centre in Ladbroke Grove.

My doctoral thesis at Cambridge was in a minute area of neuroscience and academic neurology, relating to dementia. I would never have thought that 11 years later that I would end up interested in something seemingly rather different, the design of environments in dementia.

There are a number of reasons why I believe tackling the environment in dementia is important, but I think ultimately I believe in the best quality-of-life possible for patients with dementia. In a society driven by targets, it has become very untrendy to measure quality-of-life and happiness, yet it is clear to me that well-being and happiness can impact on physical health, in ways that are not yet fully understood. This may be due to discoveries which have not happened yet in neuroimmunology, but just because we may not understand the phenomenon, it doesn’t mean that the phenomenon does not exist. Anecdotes provide that transplanting an advanced patient with dementia to a totally unfamiliar surrounding can be very distressing and detrimental to their physical health; one might wonder why on earth you would do this, but unfortunately thousands of people make this journey everyday from their home to a nursing or care home everyday.

This course, run by senior people at the University of Stirling, such as Prof. Mary Marshall, did not get unreasonably bogged down in the scientific evidence. This put me much at ease, as well as making the designers, architects and artists comfortable that their creativity and common-sense were not jeopardised. We discussed everything from corridors to balconies, but the discussions were open-minded. We considered how patients with dementia perceived their outside environment. For example, I learnt that colour constancy was relatively intact in most stages of Alzheimer’s disease, despite there being many potential ‘lower-level’ visual problems. This phenomenon relates simply to how the human brain perceives the colour of something relative to the background colour. This colour constancy is well known to have been utilised to great effect in the art work of Pier Monde.

The course, and my discussions with several Professors and Readers in the UK, make me convinced that we can see a paradigm shift in the design of better environments for patients with dementia, including better use of assistive technology and planning of houses and built environments. It would be even better, if we could bridge this drive with the cognitive, behavioural and activities-of-daily-living challenges posed by patients in their day-to-day life, but I remain confident that this can happen one day.

Dr Shibley Rahman

QS, BA (1st), MA, MB, BChir, PhD, MRCP(UK), FRSA, LLB(Hons)

A new twist in the amyloid story in Alzheimer's disease

Tracking the history of where research in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has been difficult leads you naturally to the ‘amyloid story’. Many people now believe that an alteration in brain levels of amyloid ?-proteins (A?) plays a major pathogenic role in AD, a devastating neurodegenerative disorder that causes progressive cognitive impairment and memory loss. AD is characterized by abnormal accumulation of A? in the brain, which leads to the formation of protein aggregates that are toxic to neurons. A? peptides are generated when a large protein called amyloid precursor protein (APP) is cut up into smaller pieces. However, it remains a reasonably consistent observation that the earliest symptoms in AD are early memory deficits. Why, if the build-up of amyloid is widespread, is it the memory that is most remarkable?

Recently, there was a fascinating paper from new research which helped to shed light on the events that underlie the “spread” of AD throughout the brain. The research, published by Neuron [Cell Press] in a recent issue of the journal Neuron, follows disease progression from a vulnerable brain region that is affected early in the disease to interconnected brain regions that are affected in later stages. Important for society in the future is that these findings may contribute to design of therapeutic interventions as targeting the brain region where AD originates would be simpler than targeting multiple brain areas.

The entorhinal cortex (EC) is one of the earliest affected, most vulnerable brain regions in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which is associated with amyloid-? (A?) accumulation in many brain areas. Communication between the EC and the hippocampus is critical for memory and disruption of this circuit may play a role in memory impairment in the beginning stages of AD. Neuroscientists in recent years have felt that it is the entorhinal cortex (and the perirhinal cortex of the parahippocampal cortex) that may contribute to the memory deficits of humans more than possibly the hippocampus itself.

It had not been not clear how EC dysfunction contributes to cognitive decline in AD or whether early vulnerability of the EC initiates the spread of dysfunction through interconnected neural networks. The authors of this study produced transgenic mice with spatially restricted overexpression of mutant APP primarily in neurons of the EC. Selective overexpression of mutant amyloid precursor protein (APP) predominantly in layer II/III neurons of the EC caused cognitive and behavioral abnormalities characteristic of mouse models with widespread neuronal APP over-expression, including hyperactivity, disinhibition, and spatial learning and memory deficits. Importantly, these abnormalities are similar to those observed in mouse models of AD with mutant APP expression throughout the brain.

The researchers also observed abnormalities in the hippocampus, including dysfunction of synapses and A? deposits in part of the hippocampus that receive input from the EC.

The authors concluded that this directly supports the hypothesis that AD-related dysfunction is propagated through networks of neurons, with the EC as an important hub region of early vulnerability.

This work is still entirely consistent with the exciting prospect of immunizing against amyloid in human brains one day in early Alzheimer’s disease (and the mouse models), improving function. Watch this space!

References

H. Braak and E. Braak. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. [Review.] Acta neuropathol

Volume 82, Number 4 [1991] 239-259, DOI: 10.1007/BF00308809

Julie A. Harris, Nino Devidze, Laure Verret, Kaitlyn Ho, Brian Halabisky, Myo T. Thwin, Daniel Kim, Patricia Hamto, Iris Lo, Gui-Qiu Yu, Jorge J. Palop, Eliezer Masliah, Lennart Mucke. Transsynaptic Progression of Amyloid-?-Induced Neuronal Dysfunction within the Entorhinal-Hippocampal Network. Neuron, 2010; 68 (3): 428-441

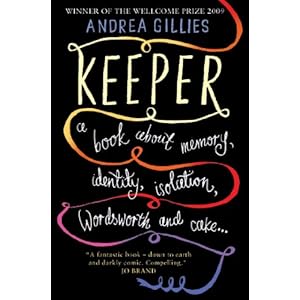

Dr Shibley Rahman : review of "Keeper" by Andrea Gillies

Andrea Gillies argues that dementia is ill-understood and remains so stigmatized that the government fails to treat it with the same urgency as other illnesses such as cancer. The historical lack of prioritization of dementia in the UK is indeed based on substantial fact and is utterly surprising, but it seems that all political parties have now pledged to remedy this despite the necessary age of financial austerity.

In her book ‘Keeper’, Andrea Gillies describes moving but unsentimental terms the day-to-day experience of caring for Nancy, her mother-in-law affected by Alzheimer’s disease. I felt the book was outstanding, explaining how a person is changed because of a real underlying disease. This book is the only one I know of which charts brilliantly a person’s cognition, personality and behaviour extremely accurately, and which is entirely in keeping of decades of research of the progression of the disease in cognitive neuroscience.

The Wellcome Trust and George Orwell prizes – richly deserved

The book has already won two prestigious awards – the Wellcome Prize, in recognition of its dispassionate analysis of the effects the disease has on the brain, and the George Orwell Prize, recognizing the author’s anger at a medical and social care system that is failing to support sufferers and their carers. The Orwell Prize is the pre-eminent British prize for political writing, and previous winners include Raja Shehadeh and Peter Hennessy.I think that the anger should be viewed in terms of improving dementia care, something which I feel passionate about, rather than any criticisms of the system. Confidence will only be undermined unless we address coherently these weaknesses.

On the Orwell panel, English PEN director Jonathan Heawood, writer Francine Stock and Andrew Holgate, literary editor of The Sunday Times, provided that Keeper is a ‘startlingly honest and vivid‘ work which goes beyond being just a memoir to examine issues such as identity and memory. ‘[Gillies] argues powerfully for change in the way we deal with age and senility, a looming political issue for the 21st century,’ the panel also commented.

While some Alzheimer’s books, such as John Bayley’s “Elegy for Iris,” are enmeshed with memories of the person before illness, Andrew Gillies intersperses her narrative with smart, very accessible narratives on the history and science of the Alzheimer’s syndrome.

Overview

At the outset of ‘Keeper’, Nancy wakes “to find that she has aged 50 years overnight, that her parents have disappeared, that she does’t know the woman in the mirror, nor the people who claim to be her husband and children, and has never seen the series of rooms and furnishings that everyone around her claims insistently is her home.”

The transition from full cognition to the cognitive and the neuropsychiatric deficits found in Alzheimer’s disease is likened to stepping through “Alice’s looking glass”.

Andrea Gillies explains that the most distressing period is when you are moving from one side to the other:

“She had one foot through the looking glass and she couldn’t make those two worlds – dementia reality, and normal life – gel at all …It was really quite science fiction in a way. Complete strangers coming into the house and saying ‘How are you today? Shall we go and have a walk?’ Obviously your reaction is going to be ‘What are you talking about? I’ve no idea who you are.’ She would awake in the morning not knowing who the man in the next bed was and she was afraid. Strangers would come into her bedroom and hand her clothes she had never seen before.”

Andrea Gillies and her husband, facing his parents’ declining health, purchased a spacious Victorian home on the Scottish coast large enough for all of them: Andrea Gillies, her husband, their three children and Nancy and her husband, Morris. The property had several acres; they kept dogs, a large garden, chickens and horses. From inside the house, they could see the rocky coast and windblown sea. ??This book is a journal of life in this wild location, in which Andrea Gillies tracks Nancy’s progression through a powerfull disease.

Memory

Early on, Nancy could express herself, but she needed help dressing, a sign of the disease’s grip. In the new house her difficulties increased: her short-term memory was degraded so that she had a hard time recognizing where she was. Indeed, problems in spatial memory is supposed to be a recognized hallmark early symptom of the disease, as the disease is centred around the medial temporal lobe initially (a part of the brain near the ear). The pattern of memory deficit is exactly as described in the seminal work of Ribot (1881), where memory for old events is relevantly preserved, compared to the encoding of new memories which is relatively impaired. “She couldn’t map her new home. Every morning she woke up thinking she had just arrived and she didn’t know where the kettle was or how to get to the bathroom. This made her angry and afraid,” according to Gillies.

In the book, it is also described that doctors initially prescribed Nancy drugs designed to stay the loss of memory, but it is not clear that these had much effect. The evidence has been that the cognitive effects of a popular group of dementia symptom-improving drugs for memory and attention, the cholinesterase inhibitors, have overall been modest, but the effects have been variable amongst recipients (with some patients, and their immediates, noting remarkable improvements).

The environment

Personally, I found the account of the enormous significance of the environment to patients with dementia incredibly powerful. the resemblance of Nancy’s new home to her childhood home provided, instead of comfort, confusion: she sometimes insisted her long-dead father was nearby. It swiftly becomes clear that they cannot look after themselves in their new home, so Gillies and her husband decide to sell up their own family home and buy a big Victorian house on a remote Scottish peninsula, moving their 10-old-year son, Jack, and his two teenage sisters into new schools and creating two separate establishments in one home, connected by a communal kitchen. The role of empowering patients with their environment instead of being unsettling can potentially be utilized to improve the quality-of-life of patients with their dementia, but this work has yet to make the huge advances it is worthy of in my opinion. Amazing progress has already been made, on a positive note.

Personality and behaviour

What makes this book special is that although it is very much an exploration of episodic memory, its loss and the subsequent erosion of personality, it is also a very useful chronicle of the effects that the onset of Alzheimer’s disease can unleashe on the extended family. It is also a chronicle of Gillies’ own unravelling, as the exhausting, realities of a carer’s role overwhelm her. Most powerful, however, is Nancy’s own voice, carefully recorded by Gillies in nightly diary entries, a voice that is at times cantankerous, bewildered, but defiant. Reading these monologues, we get very close to understanding what it feels like to experience this illness.

As the disease progresses through the brain, other areas, controlling personality and behaviour in the frontal lobes, can change a person in dementia. Some patients are mystically described by immediates as ‘changing for the better’, but Gillies is unable to give such a view of Nancy. Nancy deteriorates from a somewhat benignly forgetful doting grandmother to a raging harpy, who slaps her granddaughters, calls her beloved grandson variously a bastard, arsehole and bitch, cannot remember how to use cutlery, prefers not to wash, tucks used bits of loo paper up her sleeve, squats on the floor to pee and hides her own turds behind paperbacks in the bookshelves (“the kind of discovery that’s unexpected late at night when you’re looking for something to read”). For me, the accounts of late Alzheimer’s disease were very reminiscent of what happens, in terms of profound behavioural and personality changes, in early behavioural frontal variant frontotemporal dementia. On one occasion recounted in the book, Nancy surprises Australian guests over breakfast when she marches through the dining room wearing nothing more than a large pair of lilac briefs; they are too polite to complain.) The transformation of her mother-in-law’s personality sets Gillies on an investigation into the way the brain controls personality, concluding that identity is biological. “Selfhood isn’t something separate from your biological self,” she writes. “The brain is where your self is made.”

Reviews

“Andrea Gillies’s account of living with Alzheimer’s is the perfect fusion of narrative with enough memorable science not to choke you. It’s a fantastic book – down to earth and darkly comic in places. The judges found it compelling.” Jo Brand, Chair of the judges of the Wellcome Prize, 2009

“A wonderful book ¬– honest, upsetting, tender, sometimes angry, often funny – which takes us on a journey into dementia and explores what it means to be human.” Deborah Moggach

“Terrific, terrifying, absolutely powerful in every choice of word, every sentence… completely unflinching” Quentin Cooper

“This is one of the most moving and important books that I have read on Alzheimer’s.” John Bayley

“Thoughtful, informative and true… a very good, very necessary book.” Sir Richard Eyre, Patron of the Alzheimer’s Research Trust

“Andrea Gillies is a brilliant prose stylist with a poet’s facility for metaphor and a brave wit born of exasperation and sadness.” Professor Raymond Tallis

You can purchase “Keeper: a book about memory, identity, isolation, Wordsworth and cake…” by Andrea Gillies (www.shortbooks.co.uk) here.

Dr Shibley Rahman trained in cognitive neurology at Cambridge and in London. Although he is not a practising physician, he is an international expert in the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia, and is a freelance researcher in London.

The Alzheimer's Society Conference 2010

The atmosphere here is electric, at the University of Warwick for our Society’s conference this year.

Prof Clive Ballard, Director of Research for the Alzheimer’s Society, introduced a set of superb presentations on the latest research funded by the Society. These included an antibody against plaques in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease, the link between head trauma and Alzheimer’s disease, and the link between spontaneous cerebral emboli and subsequent risk of dementia. The poster presentations were some of the best I’ve ever seen at an academic conference, and I interpreted the address by our new CEO as looking forward to our society playing an important role in the Big Society.

Dr Shibley Rahman

My mention in the new Oxford Textbook of Medicine

My paper from Brain (1999) is cited as a seminal reference in the new Oxford Textbook of Medicine.

Download it Chapter 24.4.2

Oxford Textbook of Medicine, chapter 24.2.2. ed. Warrell, Cox and Firth. Oxford University Press, 2010.