Home » Posts tagged 'data sharing'

Tag Archives: data sharing

On international collaborative data sharing and dementia. Surely “it’s good to talk”?

Plans to harvest private data from patients’ NHS files are causing a ‘crisis of public confidence’, the Royal College of GPs said this week. The professional body said it was ‘very worried’ that the public had not been properly informed about the scheme, which is due to begin this spring. Conversely, NHS managers and public health experts say the data will be used for important research and to show up poor care – and that all the data will be made anonymous. But other experts, in information security, say patients will be identifiable from their data – which will be passed on to private companies including insurance firms, and the professional regulatory code for ethics puts valid informed consent as of prime importance. A growing number of GPs oppose the care.data scheme, and say their patients will refuse to give them information for fear it will be harvested.

In the actual Communiqué from the G8 dementia Conference, the drive of sharing of “Big Data” was formally acknowledged. In the actual webinar, there was in fact screening of a session by corporate investors on the need to minimise risk from their investments to have the regulatory framework in place to avoid concerns over international data sharing.

Indeed, BT have taken active interest in dementia.

This eye catching headline is from the BT website: :

:

This report cites that, “the goal of finding a treatment to cure or halt dementia by 2025 is “within our grasp”, Prime Minister David Cameron has said, as he announced a doubling in UK funding for research into the disease.”

“The London conference is expected to agree to a package of measures on international information-sharing and collaboration in research. ”

These concerns include data privacy and security, and curiously do not feature above.

But the report does not even mention BT’s own Paul Litchfield, who presented even in the G8 Summit.

Last year, leaders from MedRed and BT were invited by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy to unveil their new collaboration, the MedRed BT Health Cloud (MBHC), at “Data to Knowledge to Action: Building New Partnerships,” an event held at the Ronald Reagan Building 1300 Pennsylvania Ave NW in Washington, DC, on November 12, 2013.

MBHC is a multiyear, transatlantic effort to make available one of the largest open health data repositories in the world. It has been recognized by the Obama Administration as a high-impact collaboration that supports the Big Data Research and Development Initiative.

Designed to meet the converging needs of the life sciences and healthcare industries, the MedRed BT Health Cloud seeks to enhance integration of U.S. public data sets, such as adverse event reporting data from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and recently released Medicare data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, with data from the UK’s NHS and ‘other healthcare systems’.

Data currently available through the system includes several years of deidentified population health data from England, Scotland and Wales, as well as hundreds of other U.K. and data sources. It features data such as physician encounters, acute care interventions, pharmacy history, and health outcomes data.

It is argued that integration of this data with U.S. data and the addition of advanced analytics hold great potential to help speed the development of products and practices that will advance healthcare and improve the health and well-being of people around the world.

The drive for collaboration in data sharing to find a cure for dementia, most agree, is a worthy policy concern, but so is the current lack of openness in clinical data sharing which has brought about an overwhelming feeling of avoidable mistrust in the public.

The ultimate goal is the use of genomic DNA information for the development of personalised medicine.

A study testing all the DNA in the genome of cancer cells, the first of its kind reported on 7 Februrdy 2014, has identified individuals that may benefit from new treatments currently being tested in clinical trials.

Metastatic cancer – cancer that has spread from the region of the body where it first started, to other areas – is generally regarded as being incurable. In 2013, 39,620 women died from metastatic breast cancer in the US.

Progress in developing effective new chemotherapy or hormonal therapies for metastatic cancer has been slow, though there have been developments in therapies targeting specific genetic mutations in breast cancer.

We’ve all been shown Facebook adverts containing highly focused suggestions for purchases known on our known habits.

McKinseys have high hopes for the future of Big Data, indeed.

“Patients are identified to enroll in clinical trials based on more sources—for example, social media—than doctors’ visits. Furthermore, the criteria for including patients in a trial could take significantly more factors (for instance, genetic information) into account to target specific populations, thereby enabling trials that are smaller, shorter, less expensive, and more powerful.”

Of course, widespread internet access is an essential part of this technological revolution.

As regards BT, data sharing and dementia, surely it’s “good to talk” with the public who are, after all, central stakeholders?

Somebody had better tell Sid.

Should “genetic discrimination” be proposed as an amendment to the Equality Act (2010)?

One of the ways in which a district hospital differs from a large foundation trust in the NHS is that you’re more likely to take part in a drug trial or research in the large foundation trust.

Currently, European law is having to negotiate the ‘data protection’ directive.

Under EU law, personal data can only be gathered legally under strict conditions, for a legitimate purpose.

Furthermore, persons or organisations which collect and manage your personal information must protect it from misuse and must respect certain rights of the data owners which are guaranteed by EU law.

The needs of data sharing, for example by GPs and hospitals in future of the NHS, will be different from the needs of the academic research community, and somehow this will need ultimately to be reflected in our law.

The Equality Act 2010 in England and Wales is currently the key piece of legislation which allows claims of discrimination to be brought.

It bought together a number of existing laws into one place so that it is easier to use. It sets out the personal characteristics that are protected by the law and the behaviour that is unlawful. Under the Act people are not allowed to discriminate, harass or victimise another person because they have any of the protected characteristics.

Everyone in Britain is protected by the Act. The “protected characteristics” under the Act include age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion and belief, sex, and sexual orientation

When US sneezes, England catches a cold, it is alleged.

It is claimed that that many Americans fear that participating in research or undergoing genetic testing will lead to them being discriminated against based on their genetics.

Such fears may dissuade patients from volunteering to participate in the research necessary for the development of new tests, therapies and cures, or refusing genomics-based clinical tests.

To address this specific problem, in 2008 the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (“GINA”) was passed into US law, prohibiting discrimination in the workplace and by health insurance issuers. One wonders whether a genetic phenotype should be considered one day for an amendment in the Equality Act for overseeing such claims under discrimination law.

GINA prohibits issuers of health insurance from discrimination on the basis of the genetic information of enrollees. Specifically, health insurance issuers may not use genetic information to make eligibility, coverage, underwriting or premium-setting decisions.

Furthermore, issuers may not request or require individuals or their family members to undergo genetic testing or to provide genetic information.

As defined in their law, genetic information includes family medical history and information regarding individuals’ and family members’ genetic tests.

But why does this suddenly matter for “Our NHS”? The main reason is that there is a massive ‘data sharing’ drive in the UK.

There are in fact many emerging scenarios, where the empowerment of rights for patients can in fact run alongside potential apparent reasons for detriment.

Tim Kelsey, NHS England’s National Director for Patients and Information, wrote this week for NHS England:

“Transparency saves lives and it is a basic human right yet transparency, unlike heart surgery, is not mainstream in our health and care services. Last year, I took a vision to the EHI Live conference (held this week in Birmingham) to make transparency the operating principle of the new NHS. Data sharing between professionals, patients and citizens is the precondition for a modern, sustainable public service: how can we put patient outcomes at the heart of healthcare, if we cannot measure them? How can we help clinicians maximise the effectiveness of their resources, if they do not know where they are spent? How can we ensure the NHS remains at the cutting edge of statistical and medical science if we do not allow researchers and entrepreneurs safe access to clinical data?”

It is conceivable that ‘integration’ of the NHS and private insurance systems could be a feature of this future, as even this contributor to “Your Britain” observed.

MPs may wish to argue that citizens also need adequate protection, sometimes, from data sharing. This would, for example, be necessary if ever the ill-fated universal credit is integrated with health and social care personal budgets.

Currently, GINA prevents employers from using genetic information in employment decisions such as hiring, firing, promotions, pay, and job assignments.

Furthermore, GINA prohibits employers (for example, employment agencies, labour organisations, and apprenticeship programs) from requiring or requesting genetic information and/or genetic tests as a condition of employment.

It has been argued elsewhere that Beethoven might have been examples of individuals whom, if they had been tested for serious genetic conditions at the start of their careers, may have been denied employment in the fields in which they later came to excel. The jurisprudence for this issue is full of subtleties, which are discussed well in this well known blog on human rights law.

A ‘corporate capture’ of information held in the NHS has already begun, some might say. It is important that the legislature gets on top of this problem before it gets out-of-hand.

The EU Data Protection Regulation: dual challenges for proportionality in primary care and for research

According to today’s Health Services Journal, the new Caldicott Review will recommend a new duty of sharing of medical data where it is in the patients’ best interests:

“The Caldicott review into information governance in health and social care is likely to recommend a new duty to share information between agencies where it is in a patient’s best interests. In an exclusive interview with HSJ Dame Fiona Caldicott, who has been leading the review for the past year, said the six information governance principles she formulated in 1997 were still relevant today. Her previous review led to the introduction of “Caldicott guardians” responsible for data security in each organisation. However, she said her current review would propose two modifications to the rules. “We’ve suggested a new principle which is about the duty to share information in the interests of the patients’ and clients’ care,” Dame Fiona said. The move would balance a tendency towards caution over sensitive information, even where sharing it between health or care providers could lead to better care, she said.”

Sir David Nicholson yesterday conceded that he found it odd that he could be sitting around a board meeting table, and the Chief Nursing Officer of a particular trust would be regulated by his or her regulatory body, the Chief Medical Officer would be regulated likewise by his or her regulatory body, but the manager would not be professionally regulated by any body. However, as a mechanism of last resort perhaps, nobody is above the law. As described here, on 25 January 2012, the Commission published its proposal for a new ‘General Data Protection Regulation’. The proposed Regulation promises greater harmonisation – but at the price of a significantly harsher regime, requiring more action by organisations and with tough penalties of up to 2% of worldwide turnover for the most serious data protection breaches. The draft Regulation is even longer than the current Directive (95/46/EC), running to 118 pages and 139 Recitals. The draft is to be finalised by 2014 and is planned to enter into force a further 2 years after that finalised text is published in the Official Journal. This Regulation is to have powerful effects on domestic policy regarding medical data sharing for research and for medical care. Whilst the legal doctrine of proportionality governs both policy issues, they have the potential to cause unhelpful confusion.

The European doctrine of proportionality means that, ‘an official measure must not have any greater effect on private interests than is necessary for the attainment of its objective’:Konninlijke Scholton-Honig v Hoofproduktchap voor Akkerbouwprodukten [1978] ECR 1991, 2003. Exactly how the courts should approach issues of proportionality was discussed by Lord Steyn in the case of R (Daly) v SSHD [2001] 2 WLR 1622, in which he said at paragraph 27: “The contours of the principle of proportionality are familiar. In de akeitas v Permanent Secretary of Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Lands and Housing [1999] 1 AC 69 the Privy Council adopted a three-stage test. Lord Clyde observed, at p 80, that in determining whether a limitation (by an act, rule or decision) is arbitrary or excessive the court should ask itself: “whether: (i) the legislative objective is sufficiently important to justify limiting a fundamental right; (ii) the measures designed to meet the legislative objective are rationally connected to it; and (iii) the means used to impair the right or freedom are no more than is necessary to accomplish the objective.”

The response by the European Public Health Association to the report by the European Parliament’s Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs report on the proposal for a General DataProtection Regulation (2012/0011(COD)) sets out the formidable nature of this challenge.

“The European Public Health Association, representing 41 national public health associations with over 14,000 members, welcomes the proposal by the European Commission to propose a Data Protection Regulation (2012/0011(COD) that seeks to create a proportionate mechanism for protecting privacy, while enabling health research to continue. In particular, the clarity provided by these proposals will make it possible for high quality research that will benefit their citizens to be undertaken in some Member States where this has not previously been the case. However, we view with the utmost concern the amendments set out by the Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs of the European Parliament in their report dated 16.1.2013. These amendments would mean that:

- Data concerning health could only be processed for research with the specific, informed and explicit consent of the data subject (amendments 27, 327 and 334-336)

- Member States could pass a law permitting the use of pseudonymised data concerning health without consent, but only in cases of “exceptionally high public interest” (amendments 328 and 337)

- Pseudonymised data would be considered within the scope of the Regulation, even where the person or organisation handling the data does not have the key enabling reidentification (amendments 14, 84 and 85)

The consequences of these amendments for health research would be disastrous, a description that we do not use lightly. If implemented, they would prevent a broad range of health research such as that which has contributed to the saving of the lives of very many European citizens in recent decades. We are concerned that these amendments must reflect a misunderstanding of the nature of health research and the central role played by data in undertaking it, and in particular our evolving understanding of the crucial importance of obtaining unbiased and representative data on large populations so as to minimise the risk of reaching incorrect conclusions that could potentially lead to considerable harm to patients.”

And indeed the authors of that letter, Professor Walter Ricciardi (President) and Prof Martin McKee (President-Elect) [at the time of writing of that letter 21 February 2012], concluded:

“We understand the need to strike an appropriate balance between the societal need for research that can promote the health of Europe’s citizens and the mechanisms that ensure the safe and secure use of patient data in health research and the rights and interests of individuals, while noting that they themselves have an interest in being able to benefit from treatment based on research. We believe that the Commission’s proposals achieve this balance but that the proposed amendments do not and, if passed, they would have profoundly damaging implications for the future health of Europe’s citizens.”

This has been followed up with the following, taken from “The ESHG suppports an initiative of the EUPHA: “EU Data Protection Regulation has serious impact on health research” (dated 7 February 2013):

“A number of these have serious implications for health research, based on the rapporteur’s premise that “processing of sensitive data for historical, statistical and scientific research purposes is not as urgent or compelling as public health or social protection.” He gives no indication of how the evidence for urgent action for public health or social protection purposes might be obtained without research. Were the amendments to pass, the major concern is that they would mean that identifiable health data about an individual could never be used without their consent. This would mean that much important epidemiological research could not take place. For example, it would outlaw any registry-based research, such as that using cancer or disease registers. This would also make it virtually impossible to recruit subjects with particular conditions for clinical trials. The amendments would allow Member State to pass a law permitting the use of pseudonymised/key-coded data without consent, but only in cases of “exceptionally high public interest”. (Amendment 27, p24; Amendments 327 and 328, p194-195; Amendments 334-337, p198-200.) this would be an impossibly high bar for all but the most exceptional research, such as that on bioterrorism. In addition, the amendments would bring all pseudonymised/key-coded data within the scope of the Regulation, even where the person or organisation handling the data does not have the key. This would significantly increase the regulatory burden on organisations using pseudonynmised data or sharing these data with collaborators in countries outside the EU. (Amendments 13 and 14, p15-16; Amendments 84 and 85, p63-64). This would have implications not only for the soon to be 28 Member States but also for accession states implementing the acquis communitare and for those in other countries collaborating with EU researchers.”

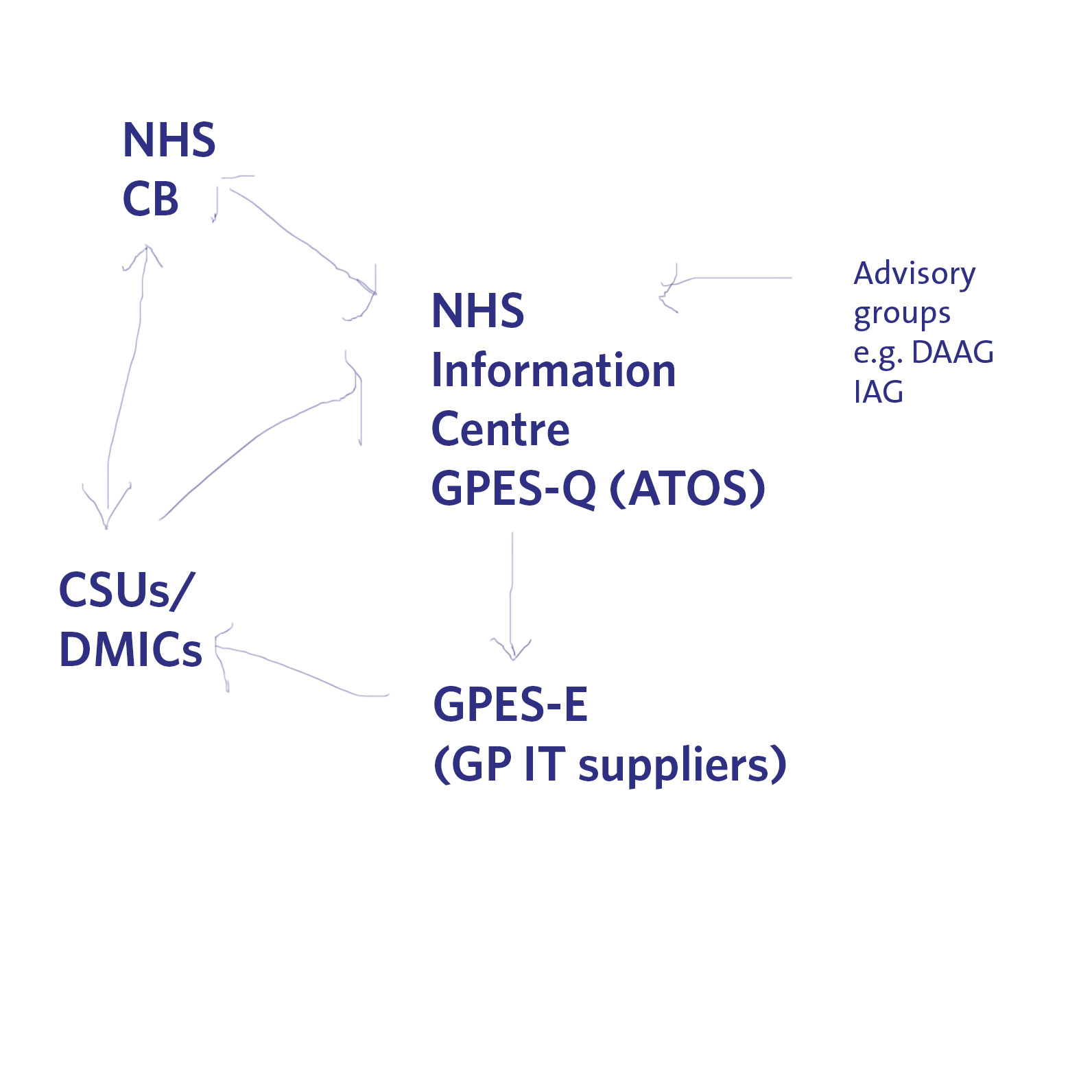

Indeed, there is another big problem looming on the horizon for data sharing of medical information. Currently ATOS is running a service which allows queries to be made of GP data (“GP extraction service”), with the main GP IT “system suppliers” providing the hardware for this to be possible in GP surgeries. The information can then be made available to DMICs (formerly the “CSUs”), and it is currently unclear how the DMIC will be processing this information legally in compliance with the Data Protection Act [1998], and the rôle of the NHS Commissioning Board in “requiring” information from the system. A very basic description of this new scheme is shown pictorially below.

The expectation is, nonetheless, that these medical data have commercial value to industry, pharma, social marketing companies, management consultancies in health, etc. as “big data”. It is argued that the prospect of commercial sale of medical data is part of the justification for government expenditure on GP data and the drive towards “integration”. Already, there is growing recognition for the need for clinical regulators to keep a careful eye on potential drifting of confidential information under the guise of ‘presumed consent’, not genuine informed consent. There is arguably a material risk that any public outcry over commercial sale of patients’ data without consent, or any major mishap in commercial handling of personal health data, may lead to justification for clamours to support the EU proposals and subsequent legislation.

However, the legal doctrine of proportionality might come back to haunt the keeping of these data somewhere in the system. In a famous unanimous judgment, S and Marper v UK (2008), delivered 4 December 2008, the European Court of Human Rights found that the retention of the applicants’ fingerprints, cellular samples and DNA profiles was in violation of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights – the right to respect for private and family life. Again, this case fundamentally rested on the legal doctrine of proportionality (full judgment here); as discussed elsewhere, the Court recognised the state had a legitimate aim in retaining DNA and fingerprints. The Court then examined whether retention was necessary in a democratic society. Certainly, the door is ajar to a test case being taken later down the line whether the GP extraction scheme is unlawful given article 8 considerations, and organisations such as Liberty may then be the most unlikelist of campaigners for patient confidentiality in reality.

These are complicated issues, but the framework for the extraction of GP data and their use, and the use of information for research in public health, appears to be the EU Data Protection Regulation. That is why it is important to get the implementation right in our domestic policy, otherwise there will be test cases brought in front of Europe in due course. Whatever the knee-jerk reaction politically to Europe and the whole issue of human rights, it is most unlikely that we will leave Europe as all three major parties have triangulated themselves into a position of being pro-EU. However, whilst the details of these discussions might be taking place behind closed doors amongst key stakeholders, they will need to be aired one day.