Home » Posts tagged 'carers'

Tag Archives: carers

Carers have to be valued, not treated as an inconvenience

I think before a physician comes to the conclusion that his or her patient has had ‘an acute deterioration of dementia’, he or she should make some effort to get a clear history of the time scale of events.

It amazed me how I was not asked at the Royal Free by any of the admitting physicians what the timescale of my mum’s decline in communication, behaviour or mobility had been. This was not a focal problem in the acute assessment and treatment area, but has been throughout the ten day admission so far.

I genuinely do wonder how useful, if at all, junior doctors are in the daily ward round of my mum with delirium, on a background of dementia. A message to you all – it is not a big success to say that my mum’s chest is clear, and proclaim she is medically fit for discharge, when she has been stuck in bed for the whole admission, her food and drink intake has fallen off a cliff, and she occasionally talks complete mumbo jumbo.

The ward round model is totally unsuited for managing delirium. The junior doctors do not involve the carers in any sort of history, and nor do any of the staff on the ward. There is absolutely no discussion of the management, including calming techniques if your mum happens to be agitated, the avoidance of chemical or physical restraints, orientation in time and place, and sleep hygiene, for example. No discussion at all.

It’s almost as if delirium was never taught at medical school to any of the staff in the hospital. To be honest, I have been totally amazed how my mum, who had suddenly fallen asleep during the middle of the day with hypoactive delirium, would have ‘nothing wrong’ in the eyes of the healthcare assistants.

It’s not enough to give carers passports, although that helps a lot. Carers need to be there to be as far as possible on the ward round, to know what medications have been crossed off without the patients’ or family’s knowledge, to know what the rough plan is, and to be able to ask questions.

It’s often the case that healthcare assistants aren’t able to feed patients with dementia. The reason for this is that it’s not just the actual food which counts, although that’s a big part of it, but also the entire mealtime environment, including how comfortable the patient feels about eating the often dire hospital food. And often the food is dumped miles away from the patient.

And if, like mum, her mobility and independence had relatively suddenly dropped off a cliff, the therapists need to know this. I’ve had absolutely no discussion or goals set by the therapists of what they hope to do with mum. Mum is a frail lady who has experienced a number of shocks, viz change of environment, weight loss, delirium, dementia, infection, dehydration, and there’s been no discussion of her frailty despite this apparently being a priority of the NHS.

There has been no discussion of her management of dementia, with her cholinesterase inhibitor having been crossed off, nor her wider needs beyond discharge. The whole thing is entirely pitiful, as if the two long term conditions my mum has been living with in the community are entirely irrelevant to this hospital admission.

And her meds for osteoporosis have been crossed off. And for her high blood pressure.

I have often thought that doctors don’t want to communicate with carers there, often because they don’t want them interfering with their ill-informed medical plans. This is hugely insulting to those of us who are 24/7 trying our best for our loved ones.

It’s not just about having a dementia friendly clock, or reminiscence room. Carers have to be valued, not treated as an inconvenience.

Money is tight, but the person remains pivotal in dementia care and support

There’s no question that there is a greater number of people who are old needing to be looked after by care and support services in England.

But dementia is not simply a disease of older people, one of the critical messages of “Dementia Friends”.

Indeed, much of the budget goes into the health and care of younger people, as health technologies, say for treating cardiovascular disease through stents, get better.

The reality is there is pressure on service and the workforce simultaneously in dementia, as the Nuffield Trust and Health Foundation have argued in a sophisticated way.

Earlier in this year, in an article for ETHOS Journal “Living well = greater wellbeing”, I argued a joined up approach would now be needed to deliver a better standard of care and support for people living well with dementia.

In 2010, the UK government became among the first countries to officially monitor people’s psychological and environmental wellbeing. Academic research and policy developments have recently converged upon the notion of ‘living well with dementia’, which transcends any political ideology. This means promoting the quality of life of any person with dementia. It views each person as a unique individual and champions his or her involvement in making decisions whenever possible.

England actually leads the way with the ground-breaking ‘first mover’ exploration by academic Tom Kitwood of ‘personhood’ in the late 1980s: “It is a standing or status that is bestowed upon one human being, by others, in the context of relationship and social being. It implies recognition, respect and trust”.

It’s estimated that there are at least 800,000 people currently living with dementia in the UK. These individuals are likely to come into contact with a number of different people and services in an extensive network including carers (paid and unpaid, including family caregivers), care home staff, transport services, social housing, welfare and benefits and the police to name but a few.

I am, indeed, grateful for Paul Burstow MP’s excellent reply to my article.

The current Government in England has made substantial progress with policy in dementia in my opinion.

The current Care Act (2014) could not be clearer.

In the statutory guidance, the importance of wellbeing is signalled extremely strongly.

It is important for commissioners not to lose sight of this, and not to treat ‘living well with dementia’ not as a slogan but as a reality.

Helping people to live well has been a key aim of the current Government, and I hope future governments, perhaps implementing ‘whole person care’, will retain this strong focus.

Enabling people to live well leads to a fairer society. The value of people living with dementia for society cannot be denied either.

But people in power and influence have a rôle to play.

The Alzheimer’s Society has played its part in addressing stigma and discrimination through its successful ‘Dementia Friends’ campaign. I myself am a “Dementia Friends Champion”, and proud to run my sessions.

One of the key messages in this campaign is that ‘there is more to the person to the dementia’.

This message is currently a critical global one, across many jurisdictions. Here is friend and colleague Kate Swaffer with a huge banner in Australia to the same effect.

And dementia and loneliness already occur together all too often.

The wider community is essential. This is about compassion. It is also about the right people showing the right leadership.

But this should not just simply include household names, although the distress caused by lack of inclusion of people with dementia in high street shops cannot be underestimated.

This community must include all caregivers and professionals.

And central to this recognition of the role of the wider community is a new deal for carers.

As the number of people living with chronic conditions grows rapidly, so does the number of carers. There is a huge army in England currently consisting of selfless individuals giving of themselves to support a loved one.

According to Carers UK, family carers currently save the Government £119 billion every year.

Carers themselves need help.

Carers are invaluable as I discuss here.

And we need to make sure in the next Government that all paid caregivers are given a statutory minimum wage, which could also be a living wage.

We are a society which values footballers more than caregivers for people with dementia. This is simply abhorrent.

I thank the current Government for progress made in this direction, but more has to be done whoever holds office and power next year.

We need collectively to support the Dementia Action Alliance Carers Call to Action. By achieving the shared vision, the aim is to have positive impact on people with dementia and carers and improve their quality of life.

In the Dementia Action Alliance “Carers Call to Action”, carers of people with dementia:

- have recognition of their unique experience – ‘given the character of the illness, people with dementia deserve and need special consideration… that meet their and their caregivers needs’ (World

Alzheimer Report 2013 Journey of Caring are recognised as essential partners in care – valuing their knowledge and the support they provide to enable the person with dementia to live well - have access to expertise in dementia care for personalised information, advice, support and co-ordination of care for the person with dementia

- have assessments and support to identify the on-going and changing needs to maintain their own health and well-being

- have confidence that they are able to access good quality care, support and respite services that are flexible, culturally appropriate, timely and provided by skilled staff for both the carer and the person for whom they care

But we do need some sort of standards, whether aspirational or regulatory, for example?

This situation had become known to Norman Lamb by February 2013:

In light of the recent Stafford Hospital Scandal, an independent review was carried out, underlining irregularities in staff training. According to today’s BBC report, as of March 2015, UK care staff and assistants in care homes, hospitals, and private homes are to be required to complete a training certificate within 12 weeks of starting a new position.

The current UK stance is that there is no minimum standard of training. With over 1million care workers in the country, it came as alarming news to Care Minister, Norman Lamb, to discover that these untrained workers were completing skilled tasks normally undertaken by medical professionals such as taking bloods. He confirmed the responsibility for the certificate would “…rest with employers and I think that’s where the training responsibility should lie.”

I expect the next Government will wish to think about a register for paid carers to help the fight against neglectful care which can tragically happen. It can be hard to achieve a successful prosecution of ‘wilful neglect’, but likewise carers need to be able to do their job with dignity and without fear.

The broad consensus has been for some time “that the principles of person-centred care underpin good practice in the field of dementia care”. Their principles assert:

- the human value of people with dementia, regardless of age or cognitive impairment, and those who care for them

- the individuality of people with dementia, with their unique personality and life experiences among the influences on their response to the dementia

- the importance of the perspective of the person with dementia

- the importance of relationships and interactions with others to the person with dementia, and their potential for promoting well-being.

In a presentation called “Developing nursing in dementia care” in May 2014 influential expert Rachel Thompson outlined a “Commitment to the care of people with dementia in hospital settings”, calling for increase in specialist nurse roles –building evidence and supporting leaders.

I believe strongly this need has not gone away. Indeed, it is stronger than ever.

Thompson there mentions the SPACE principles to support good dementia care

Staff who are skilled and have time to care.

Partnership working with carers.

Assessment and early identification of dementia.

Care plans which are person centred and individualised.

Environments that are dementia-friendly.

The financial case for ‘Admiral nurses’, an innovation from Dementia UK, is compelling; see for example the recent report from the University of Southampton Centre for Innovation and Leadership in the Health Sciences.

As is the case from the academic and clinical nursing literature on the importance of proactive case management in avoiding admissions to hospital care.

Claims that nine in ten care homes and hospitals fail to provide the proper treatment are indeed astonishing. That particular Care Quality Commission review found widespread neglect, lack of care, poor training and failings in communication.

In the same way there can be enormous disparity between a ‘bad’ and ‘good’ care home, there can be a subtle difference between a ‘very good’ and a ‘superb’ care home.

We, one day, need to be able to celebrate the ‘outstanding’ in care homes: for example, person-centred activities or environment generally might make all the difference?

The next Government, whoever it is, will need to have the confidence to implement an organic, stakeholder-driven systemic innovation in dementia.

I have long felt that the health and care services need more than a minimum ‘protected funding’. As Roy Lilley, experienced health commentator, remarks, ‘more effort can be put into weighing the pig than actually fattening it’.

This is the danger we run if we do not place adequate resources into service provision and training.

However, even within these domains, I believe that innovation has, potentially, an important and responsible part to play (as indeed I argued in the Health Services Journal this year).

There is no question that money is tight.

But we need also to have a minimum in frontline services to maintain an adequate standard of care, as indeed is supposed to be enforced from the regulation of all clinical professions.

It is easy to jump on a ‘person-centre care’ bandwagon, but all too easily this can turn into selling courses and products for person-centred care.

Putting the person at the heart of how you behave with a person with dementia does not need to cost money. Tom Kitwood articulated it brilliantly.

But, whatever the budget constraints of the health and care and future, I believe personhood should be pivotal for living well with dementia.

This should include the whole person.

If we involve people living with dementia in the design of research and services, I feel, a lot of my concerns will be addressed. The ‘Dementia Without Walls’ project from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, in collaboration with other stakeholders, has truly been outstanding, for example.

I am grateful to the current Government for taking us a long way down the journey. But we’ve only just begun.

A lack of patients’ or carers’ representative on the World Dementia Council is either an oversight or is entirely deliberate

In fairness, there’s nothing ambiguous about the stated intentions of the ‘World Dementia Council‘.

“The creation of a World Dementia Council was one of the main commitments made at the G8 dementia summit in December 2013. The council aims to stimulate innovation, development and commercialisation of life enhancing drugs, treatments and care for people with dementia, or at risk of dementia, within a generation.”

In the UK jurisdiction, there is much deep concern about the extent to which policy should be driven towards a ‘cure’ or ‘care’ for dementia.

Only this week, another story about poor standards in an English care home hit the headlines.

An undercover reporter had filmed a video appearing to show a partially paralysed woman being slapped at The Old Deanery at Bocking, near Braintree. The home’s owners have now sacked a total of seven staff and suspended one other. Essex Police said an investigation of the alleged abuse had been launched after detectives viewed the programme.

The reports of closure of day clubs and small social enterprises losing tenders stream in every week.

Meanwhile, in “Dementia Friends”, which is led by the Alzheimer’s Society, people will be given free awareness sessions to help them understand dementia better and become Dementia Friends.

By 2015, 1 million people will become Dementia Friends. The £2.4 million programme is funded by the Social Fund and the Department of Health. The scheme has been launched in England, and the Alzheimer’s Society is hoping to extend it to the rest of the UK soon.

It could be a genuine belief that industry leaders in economics, Pharma and innovations feel they do not need to listen to the views of persons with dementia or carers.

But I totally reject this hypothesis.

It is a huge kick in the teeth not to have representatives on a body actually called the “World Dementia Council”.

It is impossible for Pharma, whose primary duty is admittedly to their shareholders, to enter the ‘dementia market’ without an understanding of the needs of the market involved.

Furthermore, all innovations need to be adopted.

The work of Prof Roger Orpwood, Emeritus Professor of Medical Engineering at Bristol, is well known to many experts in dementia innovations.

Orpwood recently retired as Director of the Bath Institute of Medical Engineering (BIME) after a career in engineering design and research, initially in Industry, and then in academia and the health service.

His groundbreaking work is cited in my book “Living well with dementia”, not least because his assistive technologies for dementia through his research grants have been amazing.

I also admire the painstaking way in which he tested all his assistive technology adaptations with actual persons with dementia. This is explained in great detail in all Orpwood’s peer-reviewed papers which I have cited in my references.

I have previous reported a straw electronic poll on who were the ‘winners and losers’ of the G8 dementia summit.

96 people took part. The results clearly showed that the vast majority of people thought that large charities, corporate finance and the pharmaceutical industry were clear winners. People with dementia and carers were the clear losers, in perception.

Consistent with this, the #G8dementia summit contained little in the way of patients’ or carers’ representations relative to the needs of corporate finance, Pharma-directed research and Pharma, in the discussion sessions.

The few that appeared were outstanding through, for example Beth Britton asked a focused question on the need for more research into psychological intervention. This feeds in fact into the point there are no patients or carers representatives on the World Dementia Council, making it far less likely for high quality research into living well with dementia – which we desperately need – to be mandated.

On a happier note, Peter Dunlop gave an outstanding speech wihich received a standing ovation.

And Beth’s video was extremely special indeed for many of us.

But an explanation for the lack of patients’ and carers’ representatives on the World Dementia Council can perhaps be found in the original raison d’être of the G8 dementia summit.

Likewise, there were no patients or carers representatives at the G8 dementia summit itself, held last year in December 2012.

The general impression from my survey was that the G8 dementia summit was a ‘great opportunity’, but also a ‘waste’.

In the court of public opinion, and bear in mind that politicians and the pharmaceutical industry get their moral license to practise from their democratic acceptance, this lack of representation on the World Dementia Council has gone down like a ‘lead balloon’.

It’s simply untrue there’s a lack of good candidates of people living with dementia who could have done a brilliant job of representing views of people: Kate Swaffer and Richard Taylor immediately spring to mind.

All these shenanigans from the UK government-led policy are in total contrast to the enormous amount of warmth, goodwill and enthusiasm from the Dementia Alliance International, a stakeholder group led by people with dementia, at the Alzheimer’s Disease International conference currently under way in San Juan as we speak.

Whatever the rationale for the decision, it is incredibly bad PR for the “World Dementia Council”, raising serious questions about accountability, transparency and governance like the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge itself.

@dementia_2014 @JeanGeorgesAE @AlzheimerEurope unbelievable really

— Kate Swaffer (@KateSwaffer) May 2, 2014

@dementia_2014 @JeanGeorgesAE @AlzheimerEurope @KateSwaffer They don’t include also caring organisations. Only research and pharma.

@legalaware @RoyLilley plenty of profiteers represented? Then he will defend it relentlessly! #decisionaboutme?itwillbewithoutme!

— DiscoverThee (@DiscoverThee) May 3, 2014

— Pedro Cano (@pcanod) May 2, 2014

@Aspirantdiva @legalaware @AnnaHepburnDH @RivkahMiar Yet to be convinced. But would be nice to hope.

— Ermintrude (@Ermintrude2) May 3, 2014

@Ermintrude2 @legalaware @AnnaHepburnDH @RivkahMiar Time will tell but hope some things go above party politics, profits & national interest

— Jo Moriarty (@Aspirantdiva) May 3, 2014

@Aspirantdiva @legalaware @AnnaHepburnDH @RivkahMiar don’t like govt claiming credit when they destroy so much. And wait for applause.

— Ermintrude (@Ermintrude2) May 3, 2014

It is essential to make clear all potential conflicts of interests known of these clearly well connected people on the Council.

And if you think I am a lone voice.

I am not.

Here’s JeanGeorges CEO of Alzheimer’s Europe (@JeanGeorgesAE):

A World #Dementia Council http://t.co/iuS9KHYbu0 without people with dementia, carers or #Alzheimer associations. Not the best start!

— Jean Georges (@JeanGeorgesAE) May 2, 2014

Things can only get better. Hopefully.

Appendix

Members appointed include

Sir William Castell, Chairman of the Wellcome Trust

Dame Sally Davies, Chief Medical Officer at theDepartment of Health

Tim Evans, Director for Health, Nutrition and Population at the World Bank

Franz Humer, Chairman of Diageo plc

Dr Yves Joanette, Scientific Director, Canadian Institute of Health Research, Institute of Aging

Professor Martin Knapp, London School of Economics

Dr Kiyoshi Kurokawa, Professor of the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies and Science Advisor to the Cabinet of Japan

Yves Leterme, Deputy Secretary General of theOECD (The Organisation for Economic and Co-operation and Development)

Raj Long, Senior Regulatory Officer – Integrated Development, Global Health at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Professor Pierluigi Nicotera, Scientific Director and Chairman of the Executive Board at the German Centre for Neurodegenerative Diseases (DZNE)

Professor Ronald Petersen, Mayo Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center

Paul Stoffels, Worldwide Chairman, Pharmaceuticals,Johnson & Johnson

George Vradenburg, President and Chairman of theVradenburg Foundation and US Against Alzheimer’s

Awareness about dementia is not just public ignorance: it’s also critical to living with dementia

Often I’m struck about how the ‘awareness’ focus in dementia is making people in general public simply knowledgeable that dementia exists in 800,000 people in the UK.

But awareness about symptoms in persons living with dementia themselves is also a critical component, and cannot be factored out of the debate in current policy drive to identify the missing people undiagnosed dementia.

Policy wonks without a scientific or clinical training in dementia have become very adept at blaming GPs for underdiagnosis of dementia, but people who have some knowledge of this specialist field know that the situation is far more complicated. Other issues include perhaps a reluctance of people to seek a diagnosis because of the life-changing impact that such a diagnosis might make. There may also be nuances between different ethnic or social groups in society which might act as ‘barriers to diagnosis’. Also, some persons with dementia may be genuinely unaware of the extent of their own symptoms.

To be fair, it’s impossible for anyone who doesn’t have a diagnosis of a dementia to understand completely what living with dementia really means. Norman McNamara, who was diagnosed with dementia a few years ago at the age of fifty comments: “What can be worse than having dementia?” “It’s knowing you have dementia – it’s like having two diseases, having it, and knowing you have it.”

This is a helpful description of ‘insight’, that people with dementia can have into their own conditions. In this video, Norman reports symptoms which he knows are getting worse, and which knows are visibly getting worse to his wife, Elaine. Patients with neurological disorders are often partially or completely unaware of the deficits caused by their disease. This impairment is referred to as “anosognosia”, and it is very common in neurodegenerative disease, particularly in frontotemporal dementia.

The mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are generally poorly understood. It’s likely, however, memory for facts and events likely plays an important role. In addition, the frontal lobe systems are important for intact self-awareness, but the most relevant frontal functions have not been identified. Motivation required to engage in self-monitoring and emotional activation marking errors as significant are often-overlooked aspects of performance monitoring that may underlie anosognosia in some patients.

Another common type of dementia is a behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), characterised by a slow change in personality and behaviour, is often unnoticed by the individual himself or herself. Loss of insight is a prominent clinical manifestation of this condition, but its characteristics are poorly understood. Indeed, Mario Mendez and Jill Shapira reported in 2005 some research into what appeared to cause this lack of insight in this particular condition. They found that it is associated with low blood flows in the right hemisphere, particularly the frontal lobe, the part of the brain near the front of the head.

For the most common type of dementia, the dementia of the Alzheimer type, the generally widely-held belief is that persons experience a progressive loss of insight as the severity of dementia increases. People with this type of dementia can get particularly forgetful. Most people aren’t fully aware of their impaired abilities, which doctors describe as a “lack of insight”. This can put them at risk of injury from unsafe actions and also make them less willing to seek and comply with treatment.

However, understanding a person’s level of insight can help doctors and carers better manage their treatment and daily needs, but gauging insight can be difficult. The usual approach is to ask patients questions about their current abilities and compare their answers with those from an ‘informant’, which is usually a family member or someone else close to the patient.

But this method isn’t ideal, as it relies on the informant’s opinion of the patient’s abilities, which can be swayed by factors such as how well they know the patient and how distressing they find their behaviour.

Norman often states that ‘once you’ve met one person with dementia, you’ve met one person with dementia’. This means that for any one person with dementia there’ll be different extents of symptoms of illness, different extents of abilities, different levels of insight, and therefore different perceptions of ‘living well with dementia’. So, it is arguably difficult to compare whether one type of dementia is ‘worse’ than other?

Who were the biggest winners and losers of the G8 dementia summit? My survey of 96 persons without dementia

Background

The G8 summit on dementia was much promoted ‘to put dementia on top of the world agenda’.

It is described in detail on the “Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge” website.

I went only last Monday to Glasgow to the SDCRN conference retrospective on the G8 dementia. It was a sort-of debrief for people in the research community about what we could perhaps come to expect. And what we’d come to expect, just in case any of us had thought we’d dreamt is was the idea of identifying dementia before it had happened or just beginning to happen and stopping it in its tracks then and there with drugs.

This is of course a laudable aim, but an agenda utterly driven by the pharmaceutical industry. My philosophy (not mine uniquely) “Living well in dementia” is called “non-pharmacological interventions” to denote a sense of inferiority under such a construct.

Aim

There has never been a media report on people’s views about the G8 dementia summit.

There has never been an analysis of the messaging of this summit in the scientific press, to my knowledge.

This study was conducted as a preliminary exploratory study into the language used in a random sample of 75 articles in the English language.

Methods

I completed a survey of reactions to the G8 dementia summit held last year in December 2013. I recruited people off my Twitter accounts @legalaware and @dementia_2014, and there were 96 respondents. Responses to individual items varied from 63 to 96.

I used ‘SurveyMonkey’ to carry out this survey. With ‘SurveyMonkey’, you cannot complete the survey more than once.

(I have also already collected 19 detailed questionnaire responses from Clydebank which I intend to write up for the Alzheimer Europe conference later this year, also in Glasgow. And also six people living with dementia also responded; and I’ll analyse these replies separately. I reminded myself by looking at the programme of the summit again what the key topics for discussion were – drugs, drug development and data sharing, with a sop to innovations and provision of high quality of information. It is perhaps staggering that there has been no detailed analysis of who benefited from the G8 dementia, but given the nature of this event, the media reportage and the events of my survey, this retrospectively is not at all surprising to me.)

Exclusions

Persons with dementia were directed to a different link (of the same survey.)

Results

The results encompass a number of issues about media coverage, the relative balance of cure vs care, and who benefited.

Media coverage

Overall, most people had not caught any of the news coverage on the TV (56%) or radio (55%). But most had caught the coverage on the internet, for example Facebook or Twitter (66%). 87% of people said they’d missed the live webinar. It was possible to answer my survey without having caught of any of the G8 seminar, however.

So what did people get out of it and what did they expect? Most people did not think the summit was a “game changer” (53% compared to 16%; with the rest saying ‘don’t know’), although the vast majority thought the subject matter was significant (82%) (n = 90).

Therefore, unsurprisingly, a majority considered the response against dementia to be an opportunity for policy experts to produce a meaningful solution (58%). However, it’s interesting that 24% said they didn’t know (with a n = 90 overall.)

In summary, they had high hopes but few thought it was a good use of a valuable opportunity to talk about dementia.

Many of us in the academic community had been struck in Glasgow at the sheer “terror” in the language used in referring to dementia. A large part of the media seemed to go for a remorseless ‘shock doctrine’ approach. Prof Richard Ashcroft, a medical law and bioethics expert from Queen Mary and Westfield College, University of London, wrote a very elegant piece about this, and his personal reaction, in the Guardian newspaper.

In terms of language, the respondents were consistent in not viewing the response against dementia as a “fight” (61%), a “war” (84%), a “battle” (72%) or an “epidemic” (70%) (n ranging from 83 to 86). 56% of people considered it unreasonable to speak of “turning the tide against dementia”. In terms of personal reactions, 82% considered themselves not to be “shocked” by dementia.

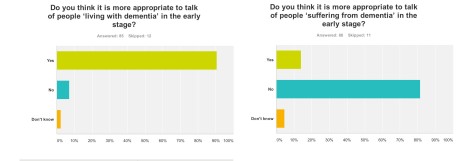

91% of people thought it was appropriate to talk of ‘living with dementia’ in the early stage (n = 85), but 82% of people did not think it was more appropriate to talk of people ‘suffering from dementia’ at this early stage (n = 86). In retrospect, I should’ve asked whether the appropriate phase was ‘living well with dementia’, so I suppose nearly 91% endorsing ‘living with dementia’ at all is not surprising. I have previously written about the use of the word “suffering”, as it is so commonly used in newspaper titles of articles of dementia here, though I readily concede it is a very real and complex issue.

The opportunity presented by the G8 dementia summit: cure vs care

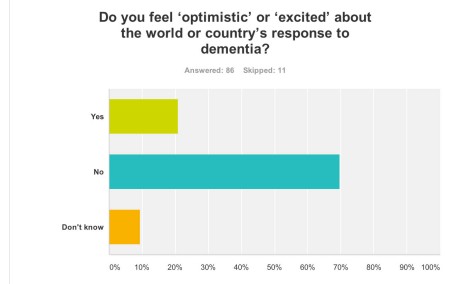

Despite all the media hype and extensive media coverage of the G8 dementia summit, 70% of people “did not feel excited about the world or country’s response to dementia” (n = 86).

But it is possibly hard to see what more could have been done.

The presentation by Pharma and politicians for their dementia agenda was extremely slick. This may be though due to a sense of politicisation of the dementia agenda, a point I will refer to below.

Early on in the meeting, World Health Organization Director-General Magaret Chan reminded the delegates – including politicians, campaigners, scientists and drug industry executives – how much ground there was to cover.

“In terms of a cure, or even a treatment that can modify the disease, we are empty-handed,” Chan said.

“In generations past, the world came together to take on the great killers. We stood against malaria, cancer, HIV and AIDS, and we should be just as resolute today,” Cameron said. “I want December 11, 2013, to go down as the day the global fight-back really started.”

It is therefore been of conceptual interest as to whether dementia can be considered in the same category as other conditions, some of which are obviously communicable. In my survey, people reported that that, before the summit, they would not have considered dementia comparable to HIV/AIDS (88%), cancer (70%), or polio (92%) (n = 86).

This is interesting, as a common meme perpetuated also by certain parliamentarians (who invariably spoke about Dementia Friends too) was that the same sort of crisis level in finding a cure for dementia should accompany what had happened for AIDS decades ago.

Biologically, the comparisons are weak, but it was argued that AIDS, like dementia now, suffered from the same level of stigma. Dementia, however, is an umbrella term encompassing about a hundred different conditions, so the term itself “a cure for dementia” is utterly moronic and meaningless.

Also in my survey, 67% of people reported that they did not feel more excited about the future of social care and support for people living with dementia (n = 85), and virtually the same proportion (66%) reported that they did not feel excited about the possibility of a ‘cure’ for dementia (defined as a medication which could stop or slow progression) (n = 85).

This reflects the reality of those people living in the present, perhaps caring for a close one with a moderate or severe dementia. It had been revealed that budget cuts have seen record numbers of dementia patients arriving in A&E during 2013. Regarding this, it was estimated that around 220,000 patients were treated in hospital as a result of cuts in social care budgets, which left them without the means to get care elsewhere.

It is known that the government has cut £1.8 billion from social care budgets, which is in addition to the pressure being applied to GP surgeries. In 2008 the number of dementia patients arriving in A&E was just over 133,000. The concern is that the Alzheimer’s Society, while working so close to deliver “Dementia Friends”, is not as effective in campaigning on this slaughter in social care as they might have done once upon a time. Currently, we now have the ridiculous spectacle of councils talking about dementia friendly communities while slashing dementia services in their community (as I discussed on the Our NHS platform recently).

Why Big Pharma should have felt the need to breathe life into the corpse of their industry for dementia is interesting, though, in itself. Pharma obviously is ready to fund molecular biology research, and less keen to fund high quality living well with dementia, and there is also concern that this agenda has pervasively extended to dementia charities where “corporate capture” is taking place. A massive theme of the G8 dementia summit was in fact ‘personalised medicine’. For example, there is growing evidence that while two patients may be classified as having the same disease, the genetic or molecular causes of their symptoms may be very different. This means that a treatment that works in one patient will prove ineffective in another. Nevertheless, it is argued the literature, public databases, and private companies have vast amounts of data that could be used to pave the way for a better classification of patients. According to my survey, despite ‘personalised medicine’ being a big theme of the summit, strikingly 66% felt that this was not adequately explained. There’s no doubt also that the Big Pharma have been rattled by their drugs coming ‘off patent’ as time progresses, such as donepezil recently. This has paved the way for generic competitors, though it is worth noting that certain people have only just given up on the myth that cholinesterase inhibitors, a class of anti-dementia drugs, reliably slowed the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in the majority of patients.

Who benefited?

In terms of who ‘benefited’ from the G8 dementia summit, I asked respondents to rate answers from 0 (not at all) to 5 (completely).

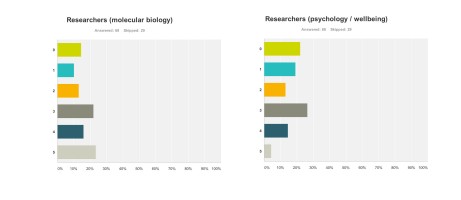

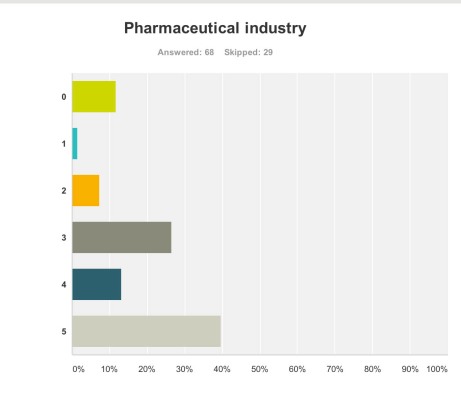

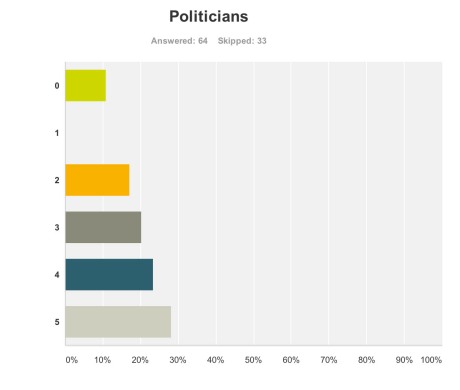

Research First of all, it doesn’t seem researchers themselves are “all in it together”. For example, these are the graphs for researchers (molecular biology) (n = 68) and researchers (wellbeing) (n = 68), with rather different profiles (with the public perceiving that researchers in molecular biology benefited more). This can only be accounted for by the fact there were many biochemical and neuropharmacological researchers in the media coverage, but no researchers in wellbeing.

Pharmaceutical industry But the survey clearly demonstrated that the pharmaceutical industry were perceived to be the big winners of the G8 dementia (n = 68).

Ministers are hoping a government-hosted summit on dementia research will help boost industry’s waning interest in the condition, and to some extent campaigners have only themselves to blame for pinning their hopes on this one summit.

The G8 Summit came amidst fears the push to find better treatments is petering out, and it is still uncertain how effective some drugs currently in Phase III trials might be, given their problems with side effects and finding themselves into the brain once delivered.

And the breakdown is as follows:

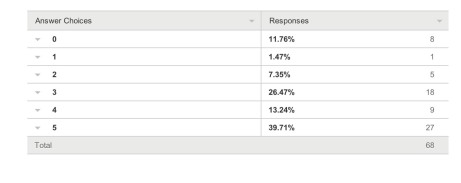

Charities The survey also revealed a troubling faultline in the ‘choice’ of those who wish to support dementia charities, and potential politicalisation of the dementia agenda. It has been particularly noteworthy that this recent initiative in English policy was branded “the Prime Minister Dementia Challenge”, and ubiquitously the Prime Minister was (correctly) given credit for devoting the G8 to this one topic.

A previous press release had read,

“Launched today by Prime Minister David Cameron, the scheme, which is led by the Alzheimer’s Society, people will be given free awareness sessions to help them understand dementia better and become Dementia Friends. The scheme aims to make everyday life better for people with dementia by changing the way people think, talk and act. The Alzheimer’s Society wants the Dementia Friends to have the know-how to make people with dementia feel understood and included in their community.. By 2015, 1 million people will become Dementia Friends. The £2.4 million programme is funded by the Social Fund and the Department of Health. The scheme has been launched in England today and the Alzheimer’s Society is hoping to extend it to the rest of the UK soon. Each Dementia Friend will be awarded a forget-me-not badge, to show that they know about dementia. The same forget-me-not symbol will also be used to recognise organisations and communities that are dementia friendly. The Alzheimer’s Society will release more details in the spring about what communities and organisations will need to do to be able to display it.”

Therefore, the perception had arisen amongst the vast majority of my survey respondents that large charities were big winners from the G8 dementia summit. This is perhaps unfair as there was not much representation from other big charities apart from the Alzheimer’s Society, for example Dementia UK or the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

I feel that this distorted public perception in the charity sector for dementia is extremely dangerous.

And this finding is reflected in the corresponding graph for ‘small charities’. Small charities were not represented at all in any media coverage, save for perhaps ambassadors of smaller charities there in a personal capacity at the Summit.

The numbers sampled for their views on large and small charities were both 67.

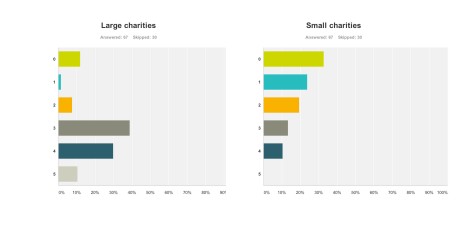

Paid carers and unpaid caregivers

The major elephant in the room, or maybe more aptly put an elephant who wasn’t invited to be in the room at all, was the carers’ community.

Only recently, for example, it’s been reported from Carers UK that half of the UK’s 6.5 million carers juggle work and care – and a rising number of carers are facing the challenge of combining work with supporting a loved one with dementia. The effects of caring for a person with moderate or severe dementia are known to be substantial, encompassing a number of different domains such as personal, financial and legal. It is also known that without the army of millions of unpaid family caregivers the system of care for dementia literally would collapse.

These are the graphs for paid (upper panel) and unpaid (lower panel) carers and caregivers (n = 65 and n = 66 respectively), with the most common response being “not at all benefiting”.

Politicians

But when asked if the politicians benefited, the result was very different.

Admittedly, few politicians were in attendance from the non-Government parties in England, and none from the main opposition party was given an opportunity to give a talk.

Both Jeremy Hunt and David Cameron gave talks. There is clearly not a lack of cross-party consensus on the importance of dementia, evidenced by the fact that the last English dementia strategy ‘Living well with dementia’ was initiated under the last government (Labour) in 2009.

The overall impression from 64 respondents to this question that politicians benefited, and some thought quite a lot.

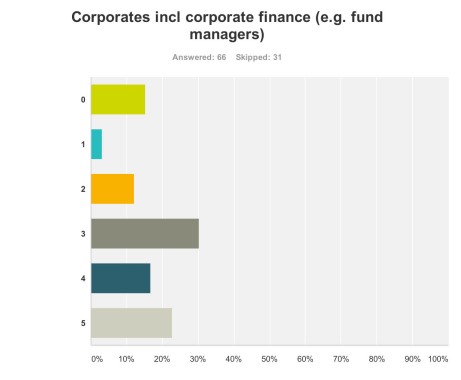

Corporate finance A lot of discussion was about ‘investment’ for ‘innovation’ in drug research. Andrea Ponti is a highly influential man. He has been Global Co-head of Healthcare Investment Banking and Vice Chairman of Investment Banking In Europe of JPMorgan Chase & Co. since 2008. Mr. Ponti joined JPMorgan from Goldman Sachs, where he was a Partner and Co-head of European healthcare, consumer and retail investment banking, having founded the European healthcare team in 1997.

At the G8 dementia summit, Ponti advised that biotechnology and drug research can be a ‘risky’ investment for funders, rebalance of risk/reward needed. Ponti specifically made the point the rewards for investing in drug development had to be counterbalanced by the potential risks in data sharing (which are not insubstantial legally across jurisdictions because of privacy legislation).

Anyway, in summary, it was perhaps no surprise that my survey respondents felt that corporate finance were big winners of the summit (n = 65).

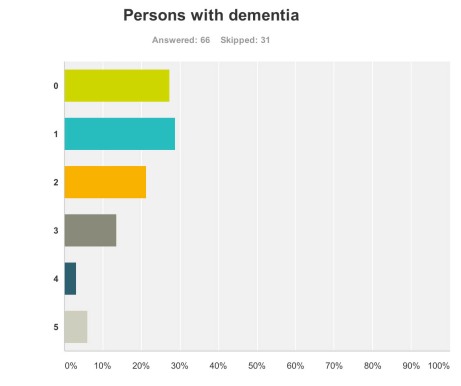

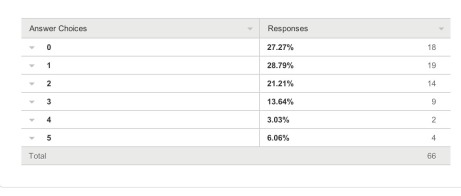

Persons with dementia And also for persons with dementia themselves?

One would have hoped that they would have been big winners according to my survey respondents, but the graph shows a totally different profile (with a minority of respondents rating that they benefited much.)

This is very sad.

66 answered this question.

The overall picture was this.

And the breakdown of results was this.

What will people do next?

Finally, it seemed as if the G8 Dementia Summit produced a ‘damp squib’ response with people in the majority neither more or less likely to donate to dementia charities (69%), donate to dementia care organisations (74%), get involved in befriending initiatives (72%), talk to a neighbour living with dementia or talk to a caregiver of a person living with dementia (58%), or get involved in dementia research (69%) (n varying from 73 to 78).

Limitations

Respondents were all in the UK, but the G8 dementia summit was clearly targeted in a multi-jurisdictional way.

It could be that there is huge bias in my sample, towards people more interested in care rather than Pharma. My follower list does include a significant number of people living with dementia or who have been involved in caring for people with dementia.

Conclusion

It would be interesting to know of any in-house reports from other organisations as to how they perceived they felt benefited from the G8 dementia, for example from patient representative groups, Big Pharma, carers and the medical profession. Pardon the pun, but the results taken cumulatively demonstrate a very unhealthy picture of the public’s perception in the dementia agenda in England, who calls the shots, and who benefits.

Given that this G8 dementia was to a large extent supposed to establish a multinational agenda until 2025, in parallel to the multinational nature of the response of the pharmaceutical industry, for those of us who wish to promote living well with dementia, it is clear some people are actually the problem not the solution.

This is incredibly sad for us to admit, but it’s important that we’re no longer in denial over it.

In “Big Dementia”, who cares about dementia carers?

Without the work of unpaid carers, the formal care system would be likely to collapse. Some feel that the State gets a “very good deal” out of this current system. The ongoing support from unpaid carers will be a particular issue for the care system in the future, as changing demographic patterns, shifts in family composition, labour force participation and increased geographical mobility will affect the availability of the unpaid care workforce. There are also significant issues emerging in care work.

It can be argued that some carers in dementia, whether unpaid carers or paid care workers, are perceived rather unfairly by society, and this is a matter of real national concern. The issue of researching personalised medicines, and pooling clinical drug trial data, across a number of different jurisdictions, is a curiously international phenomena. It feeds into the ‘big is better’ narrative, which is of course a key aspect of why large multinational companies like ‘Big Data’. But converting our response to dementia to a solution for Big Pharma is not solely the answer. The answer is not simply ‘Big Dementia’, much as that might be attractive for the corporates. It is just as crucial to consider who cares about dementia carers. The two are not necessarily mutually exclusive of course. In an ideal world, we should like to offer the best care for people with dementia, as well as effective symptomatic treatment as well as a cure. However, it’d be a disaster if we could hold our hands up, and say that we could in all reality offer neither. As the international economies recover after the global financial crash, caused by the effects of poor global regulation of securitised mortgage products, it might seem fitting that the international landscape can be tweaked to make dementia profitable for Big Pharma. However, it is clear that our own national parliament, in the recent ‘dementia care and services’ debate on 7 January 2014, wishes to have a frank and sincere debate about who cares for the carers. As a society, this is dependent on economics within our control. If people need to talk about about the ‘cost’ of dementia relentlessly, there might be an equal and opposite need to talk about the value of carers; and this needs to be a national debate.

The usual tired mantra from politicians would of course be trotted out, particularly from those of a certain political inclination, that as the economy improves our living standards will improve. But it has been a concern of all main political parties that living standards for the many are not expected to rise as the economy recovers. In this jurisdiction, there’s a particular phenomenon of how the very wealthy seem to have been relatively immune from the global financial crash. This ‘cost of living crisis’ has been partly attributed to big corporates colluding legally to maintain prices to promote shareholder dividend rather than customer value. In England, the Health and Social Care Act (2012) was legislated by the current government to promote a quasi-market in the NHS in England. The aim was to introduce competition, bolster an economic market regulator, and to produce a mechanism for fast managed decline of ‘failing’ NHS Foundation Trusts. Clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) and health and wellbeing boards were also introduced new parts of the NHS in England. CCGs plan and buy local health services, while health and wellbeing boards influence the local decisions that shape health, public health and social care. In this new political and socio-economic landscape, it has been particularly striking, but encouraging, that the shared vision of the “Dementia Action Alliance” is of an England and Wales where the health and wellbeing of carer of a person with dementia are of equal priority to those of the person for whom they care. Ideally, for competition to thrive, it should not be in the hands of a few corporates and corporate-like charities, but all stakeholders should be given a fair slice of the action.

The wellbeing of carers of dementia in England is related to both its national economy and law, and this is something which is not within the powers of the G8 arena. In keeping with previous Conservative governments, George Osborne has warned that “self-defeating” increases to the minimum wage could “cost jobs”, and John Major, the Prime Minister 1990-7 had argued strongly the dangers of the national minimum wage. Many of the same arguments are likely to resurface as the UK Labour Party will undoubtedly raise the importance of the “living wage”, prior to the general election to be held on May 7th 2015. Cabinet ministers including Business Secretary Vince Cable and Work and Pensions Secretary Iain Duncan Smith are reportedly pressing, currently, for an “above-inflation rise” of 50p or more. Mr Osborne said he too wanted to see the £6.31 hourly minimum wage rise, but he said it should be left to the Low Pay Commission to set the appropriate level.

As Norman Lamb said in the parliamentary debate the other day, “We ask carers to do some of the most difficult work that one can ever imagine but the rewards and the training and support they get is minimal.”

An emerging political consensus has promisingly emerged that “we can never get good care on the back of exploiting very low-paid workers”, as Lamb put it. It turns out that carers are currently paid the national minimum wage if they are lucky. That is, of course, a breach of the minimum wage legislation. According to an authoritative study Dr Shereen Hussein, of King’s College London, estimates that there are between 150,000 and 220,000 care workers in this position. And this is using conservative assumptions – the real number could be higher. The flouting of national minimum wage has, however, become alarmingly widespread. There are a variety of employment practices that result in the minimum wage being circumvented, the most common of which is when councils sign contracts with private providers who recruit staff to provide short slivers of care in the home. A quarter of an hour can be all that a care worker gets to wash, change, feed and talk to someone with dementia. Dignity for the client is often the first casualty: a variety of groups representing the vulnerable, as well as some of the more scrupulous employers, fear that rushed care contracted by the minute often means inadequate care. Previous findings suggest almost half of councils still set 15 minutes as their minimum time slot.

Furthermore, many paid care workers are on zero-hours contracts. Unison’s ethical care charter aims to put an end to poor pay and working conditions in home care services. Under the charter, for example, Islington council has agreed to implement the charter’s main principles of getting rid of zero hour contracts, ensuring travel time is counted in employees’ paid hours and implementing the London living wage, as well as setting up occupational sickness schemes. Islington, alongside Southwark council, has been an early adopter of the recommendations put forward by Unison in the their report into home care. Published in 2012, the report found that good carers were being lost to “easier jobs that pay more, like in supermarkets” after finding themselves unable to support their family on an inadequate and unreliable salary.

Many paid care workers also do not get paid for travelling between the appointments they undertake, but clearly care workers must be paid when they are travelling from one home to another. Furthermore it is common for remuneration systems to pay only pay per minute actually spent with clients, not the travel time between them. Dozens of these work-related journeys could be made each week as it’s a core part of the job. Not being paid for this time means those who care don’t get paid for a full day’s work.

It is also important for councils commissioning care work to be absolutely clear with those they contract with that they expect total compliance with the law. If a council is commissioning in a way which almost becomes complicit in a breach of the law, that is completely unacceptable. On the other hand, NHS Wiltshire has commissioned an “outcomes based continuing healthcare service” designed to improve quality, reduce cost and link up with social care – but which completely restricts patient choice. The “Help to Live at Home” service has been commissioned jointly with Wiltshire Council. Contracts for the £23m service. The provider a patient receives will depend on where in the county they live. All health and social care services will be delivered by that provider and payment will depend on achieving a set of agreed outcomes.

There is a big difference between “care workers” and “unpaid carers”. A phenomenon worth keeping an eye on is that of “family caregiving” which has been on an upward trend in various jurisdictions, in part due to the economic recession. Some families lack the financial capabilities to pay professional caregivers. In fact, a huge group of carers comprise the “unsalaried family caregivers”. Family caregivers of people with dementia, often called the “invisible second patients”, are critical for people living with dementia. The effects of being a family caregiver, can be both positive and negative, with high rates of burden and psychological morbidity as well as social isolation, physical ill-health, and financial hardship. Indeed, it is mooted that comprehensive care of a person with dementia can include building a partnership between all health professionals and family caregivers. Many family caregivers of people with dementia might also employed, of whom many have reported that they missed work; a proportion may have even that turned down promotion opportunities or given up work to attend to caregiving responsibilities. There is furthermore no doubt that the benefit system is confusing, and it had been hoped that universal credit would be a method of simplying that. If you care for someone with dementia, you are normally advised to check that you are both getting all the benefits and tax credits you are entitled to. For example, you may be able to claim Personal Independence Payment or Attendance Allowance for the person with dementia, and Carer’s Allowance for the carer. You, or the person you look after, may be entitled to a discount on your council tax. Again, the situation can be complicated, and many people get simply put off from applying for the benefits for which they could be entitled due to sheer complexity and/or lack of guidance.

So, how will we eventually know when carers are being looked after? We will hear that carers of people with dementia are confident that their own health and wellbeing needs and requirements are recognised and supported, so that no carer feels alone, and are given regular breaks. This is in keeping with how local and national guidance for working time should be implemented anyway. Carers of people with dementia are also recognised as essential partners in care, assuming an approach which could be best called “coproduction”. Furthermore, carers of people with dementia would also have access to expertise in dementia care for information, advice, support and co-ordination of care. The “Dementia Action Alliance” has been the coming together of over 800 organisations to deliver the National Dementia Declaration; a common set of seven outcomes informed by people with dementia and their family carers. The Declaration provides an ambitious and achievable vision of how people with dementia and their families can be supported by society to live well with the condition

It would be incredibly valuable to have carers have a voice on CCGs and health and wellbeing boards, especially since commissioners are supposed to be promoting wellbeing pursuant to the Care Bill currently being discussed in the House of Commons and the House of Lords. The demands of caring for someone with dementia are great and many carers say they feel totally unsupported. How to include unpaid care workers in this commissioning debate is undoubtedly a difficult issue, but one which simply cannot be ultimately parked for convenience.

“Big Dementia” may not provide all of the answer, unless care is combined with cure.