Home » Posts tagged 'Care data'

Tag Archives: Care data

Should you give data altruistically, like you donate blood?

“Alongside what we have already done with the mandatory work programme and our tougher sanctions regime, this marks the end of the something-for-nothing culture,” Duncan Smith said in a conference speech for the Conservative Party last year.

The “something for nothing” meme, reinforced by the concept that “there is no such thing as society” (which Thatcher supporters vigorously claim now was ‘misunderstood’), remains a potent policy narrative.

The anguish which NHS England has experienced may be due to a fundamental problem with trust, as for example demonstrated elsewhere in reaction to GCHQ or NSA. But it could well be due to the “something for nothing” meme coming back to haunt the Government, which narked off public health specialists as the “opt out” has become unhelpfully enmeshed with concerns about commercial profiteering from health data.

“The Blood Donor” is a famous episode from the comedy series “Hancock”, the final BBC series featuring British comedian Tony Hancock. First transmitted on 23 June 1961, Anthony Hancock arrives at his local hospital to give blood. “It was either that or join the Young Conservatives”, he tells the nurse, before getting into an argument with her about whether British blood is superior to other types.

The issue of consent has predictably come to the fore, and it is generally felt that the communications strategy of NHS England over caredata went very badly wrong.

In an almost parallel universe, nothing to do with blood donations, it turns out that Labour is looking at bringing in a US-style system of allowing voters to register on election day amid growing fears that millions of people are about to drop off the official register in a “disaster for democracy”.

In a radical move, Labour is considering allowing same-day registration, which is credited with boosting turn-out from around 59% to 71% in some American states, according to the Demos think-tank. But the point is: mass paperwork involving the population at large is possible.

But now the issue has also become “there is no such thing as altruism”.

The Coalition announced in September 2013 that it had sold Plasma Resources UK to Bain Capital, the private equity firm. Plasma Resources UK (PRUK) turns plasma, the fluid in blood that holds white and red cellsin suspension, into life-saving treatments for immune deficiencies, neurological diseases and haemophilia.

The deal was hugely controversial, beyond typical disagreements over privatisation of national assets, because blood transfusions in the UK are voluntary; if donors think that someone is going to make a profit from their donation, they may well not give blood at all.

Richard M. Titmuss was a professor of social administration at the London School of Economics form 1950 until his death in 1973. He had an international reputation as an uncompromising analyst of contemporary social policy and as an expert on the welfare state.

Richard M. Titmuss’s “The Gift Relationship” (recently edited by Ann Oakley and John Ashton) has long been acknowledged as one of the classic texts on social policy.

A seemingly straightforward comparative study of blood donating in the United States and Britain, the book elegantly raises profound economic, political, and philosophical questions. Titmuss contrasts the British system of reliance on voluntary donors to the American one in which the blood supply is largely in the hands of for-profit enterprises and shows how a nonmarket system based on altruism is more effective than one that treats human blood as another commodity.

His concerns focused especially on issues of social justice. The book was influential and, indeed, resulted in legislation in the United States to regulate the private market in blood.

But shouldn’t you simply donate data ‘for the public good’, in the same way you can choose to donate blood?

The start of a new data sharing scheme involving the pseudonymised medical records of those who do not opt out will be postponed to give patients more time to learn about its benefits and safeguards, NHS England has announced.

Part of the semantics of the legal data involves whether a discussion of the giving of data is ultimately separable from the discussion of the purposes for which these data are ultimately applied.

HSCIC, Health Statistics Collaboration with Insurance Companies, reported on its insurance collaboration intentions last August. Section 2.3.1 of its Information Governance Assessment Addendum stated their intentions very clearly, as Roy Lilley earlier pointed out.

“There is no legal requirement to differentiate between the release of data to NHS commissioners and any other potential data recipient. In the eyes of the law, a government department, a university researcher, a pharmaceutical company, or an insurance company is as entitled to request and receive de-identified data for limited access as a clinical commissioning group, as long as the risk that a person will be re- identified from the data is very low or negligible.”

“Furthermore, all such organisations can make good use of the data. Access to such data can stimulate ground-breaking research, generate employment in the nation’s biotechnology industry, and enable insurance companies to accurately calculate actuarial risk so as to offer fair premiums to its customers.”

The Centre for the Study of Incentives in Health in London is a cluster of academics looking at the pros and cons of whether incentives can influence behaviour.

The issue of paying individuals to change their behaviours in health-enhancing ways, for example by encouraging them to quit smoking or take regular exercise, is a highly topical policy issue, in the UK and internationally. Yet personal financial incentives are potentially riddled with legal ethical issues, with concerns regarding their precise effectiveness, and with further concerns that they may have unintended consequences.

Paying people to undertake particular actions may crowd out their intrinsic motivations for wanting to do those actions, as demonstrated by Richard Titmuss’ classic work on blood donations almost forty years ago

Arguably, a final nail in the coffin came from a report by Randeep Ramesh that drug and insurance companies might be able to, from later this year, buy information on patients – including mental health conditions and diseases such as cancer, as well as smoking and drinking habits – once a single English database of medical data has been created.

However, advocates argued that sharing data will make medical advances easier and ultimately save lives because it will allow researchers to investigate drug side effects or the performance of hospital surgical units by tracking the impact on patients.

Possibly, now is an opportune time to revisit Richard Titmuss’ thesis.

One can only speculate what he would have made of the current furore over ‘caredata’. I suspect though he would care.

Are we actually promoting the NHS ‘choice and control’ with the current caredata arrangements?

In the latest ‘Political Party’ podcast by Matt Forde, an audience member suggests to Stella Creasy MP that wearing a burkha is oppressive and should not be condoned in progressive politics. Stella argued the case that she can see little more progressive than allowing a person to wear what he or she wants.

The motives for why people might wish to ‘opt out’ are varied, but dominant amongst them is a general rejection of commercial companies profiteering about medical data without strict consent. This is not a flippant argument, and even Prof Brian Jarman has indicated to me that he prefers a ‘opt in’ system:

Patients are not fully informed about how their information will be used. For such confidential data they should have to opt in @legalaware

— BrianJarman (@Jarmann) January 28, 2014

If people are properly told the pros and cons they can decide if they want to accept the cons, for the sake of the pros @sib313 @legalaware

— BrianJarman (@Jarmann) January 27, 2014

There are potential benefits, but also risks and if the risks happen they’re irreversible. Hence it’s safer to have opt-in. @legalaware

— BrianJarman (@Jarmann) January 27, 2014

Opting out can be argued as not being overtly political, though – it is protecting your medical confidentiality. People may (also) have political reasons for doing this, but the choice is fundamentally one about your right to a private family life. The government (SoS) has accepted this, and that is why it is your NHS Constitution-al right to opt out – you don’t have to justify it and if you instruct your GP to do it for you, she must.

It’s argued fairly reliably that section 251 of the NHS Act 2006 maps exactly onto Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 2001. Section 60 was implemented the following year under Statutory Instrument 2002/1438 The Health Service (Control of Patient Information) Regulations 2002. It is argued that the Health and Social Care Act 2012 did not modify or repeal those provisions of the HSC Act 2001 or the NHS Act 2006, nor did it modify or repeal any related provision of the Data Protection Act 1998. SI 2002/1438 remains in force. However, noteworthy incidents did occur under this prior legislation, see for example this:

Whatever motive you have for arguing against care.data, whether the whole principle of it, the HSCA removing any requirement for consent, the fact that it is identifiable data being uploaded from GP records (i.e. not anonymised or pseudonymised), or that the data will be made available, under section 251, for both research and non-research purposes, to organisations outside of the NHS, etc, the matter remains that the is no control over your data unless you opt-out.

Proponents of the ‘opt out’ therefore propose their two lines of action: either prevent your identifiable data being uploaded (9Nu0) and so effect a block on the release of linked anonymised or pseudonymised (potentially identifiable) data, which otherwise you cannot prevent or control; or block all section 251 releases (9Nu4), whether or not you apply the 9Nu0 code.

The point is, they argue, that you – the patient – cannot pick and choose, when, to whom, or for what purposes your data will be released. You cannot prohibit your data from being released for purposes other than research, or to organisations out with the NHS. This is completely at odds to the ‘choice and control’ agenda so massively advanced in the rest of the NHS. While it has been argued that the arguments against commercial exploitation of these data should have been made clearer beforehand, it’s possibly a case ‘I know we’re going there, but I wouldn’t start from here.’

Compelling arguments have been presented for the collection of population data. It’s argued wee need population data to do prevention and to monitor equity of access and use. It’s an open secret that the current Government is continuing along the track of privatising the NHS; arguably making it all the more important to have good data so we know what is happening. Having more of this data at all starting in the private sector, under this line of argument, is much less transparent, as it’s hidden from freedom of information from the start.

It’s, however, been argued that “the route to data access” has in fact changed. Under Health and Social Care Act (2012), it was intended that either the Secretary of State (SoS) or NHS England (NHSE) could direct HSCIC to make a new database, and – if directed by SoS or NHSE – HSCIC can require GPs (or other care service providers) to upload the data they hold. care.data represents the single largest grab of GP-held patient data in the history of the NHS; the creation of a centralised repository of patient data that has until now (except in specific circumstances, for specific purposes) been under the data controllership of the people with the most direct and continuous trusted relationship with patients. Their GP.

HSCIC is an Executive Non Departmental Public Body (ENDPB) set up under HSCA 2012 in April 2013. NHS England, the re-named NHS Commissioning Board, was established on 1 October 2012 as an executive non-departmental public body under HSCA 2012. Therefore, to suggest that the government has ‘little control’ over these arm’s-length bodies is being somewhat flimsy in argument – they were both established and mandated to implement government strategy and re-structure the NHS. There are also problems with the “greater good” argument; being paternalistic, the opposition to caredata spread bears similarity to the successful opposition to ID cards. This argument presumes that patients will benefit individually, when – and it ignores the fact that it is neither necessary or proportionate –and may be unlawful under HRA/ECHR – to take a person’s most sensitive and private information without (a) asking their permission first, and (b) telling them what it will be used for, and by who. Nobody is above the law, critically.

The fact is that the data gathered may increment the data available to research but that in its current form, care.data may actually not be that useful – it includes no historical data, for starters. And all this of course ignores the fact that care.data (and the CES that is derived from linking it to HES, etc.) will be used for things other than research, by people and companies other than researchers. That is the linchpin of the criticism. Finally, the Care Bill 2013-14 – just about to leave Committee in the Commons – will amend Section 251, moving responsibility for confidentiality from a Minister (tweets by Ben Goldacre here and here).

Anyway, the implementation of this has been completely chaotic, as I described briefly here on this Socialist Health Association blog. What now happens is anyone’s guess.

The author should like to thank Prof Ross Anderson, Chair of Security Engineering at the Computer Laboratory of the University of Cambridge, Phil Booth and Dr Neil Bhatia for help with this article.

Cameron’s #CostofNHSConfidentialityCrisis

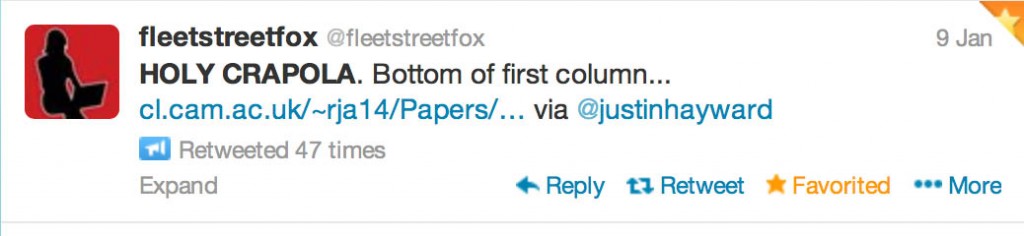

Thanks to @fleetstreetfox for tweeting this last night.

And THIS tweet refers to THAT sentence (see bottom of the first column):

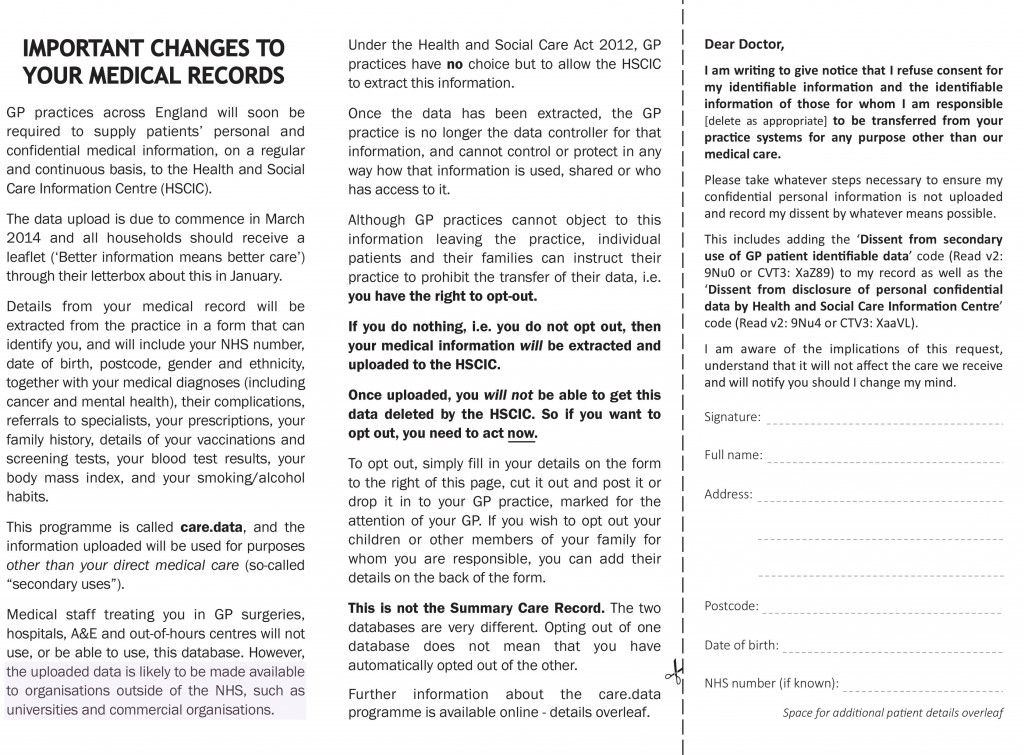

You have just eight weeks to opt out of having your and your family’s confidential medical information uploaded from your GP’s systems, then passed on or sold to others – including private companies.

For more information, see www.medconfidential.org where you can download an opt out form, should you wish to opt out.

And please do pass these links on:

www.medconfidential.org/how-to-opt-out

for a copy of the form and a letter for you to use, if you prefer

www.care-data.info for detailed information on the care.data programme by the GP who wrote the content of the opt out form

for a direct link to a PDF of the form for use on Twitter, etc.

Keep safe.

I would like to propose a SHA committee on the use of GP data in the NHS

The GP-patient consultation is a pivotal part of everyday activity of the NHS. Whilst the reasons that a patient may decide to go to see his or her GP are diverse, it is clear that much information is exchanged in that consultation. Some of that information will be relevant for deciding upon the need for further investigations and examination, and even possible referral to other parts of the NHS. The data might therefore very useful at an individual level. However, the data, taken as a whole for a population, might also produce useful insights which are relevant for further research, and are therefore enormously beneficial for public health.

The GP-patient consultation is a pivotal part of everyday activity of the NHS. Whilst the reasons that a patient may decide to go to see his or her GP are diverse, it is clear that much information is exchanged in that consultation. Some of that information will be relevant for deciding upon the need for further investigations and examination, and even possible referral to other parts of the NHS. The data might therefore very useful at an individual level. However, the data, taken as a whole for a population, might also produce useful insights which are relevant for further research, and are therefore enormously beneficial for public health.

When a patient goes to see his/her own GP, normally the patient has an expectation that the consultation will be confidential. This is at the crux of the doctor-patient relationship.

1. Medical confidential data from an individual perspective

From April 1st 2013 there was a noteworthy change to the way in which the Department of Health collected information about patient health from GP record systems in England. Previously, mainly aggregate health data was collected and patients could sometimes opt out of having identifiable information from their own record uploaded to central systems. From April 1st, the newly-renamed NHS “Health and Social Care Information Centre” (HSCIC) began uploading identifiable patient information, without telling patients how they can opt out of this process – or even that they can. The data uploaded included every patient’s NHS number, date of birth, postcode and ethnicity, together with details of medical conditions, diagnoses and treatments.

That information is held on HSCIC and other NHS systems where it will be used to analyse health trends and demand for services, improve treatment and provide evidence upon which local clinical commissioning groups can base decisions about service provision. The data will also be made available to outside parties such as researchers and for-profit companies, and this is where the concern that “data will be sold to the highest bidder” has emerged from in the recent media (see for example the Guardian, “£140 buys private firms data on NHS patients”, article by Randeep Ramesh @tianran 17 May 2013). The HSCIC say that it will be ‘anonymised’ before release, but the concept of anonymisation is highly controversial and it is unlikely that guarantees can be given about the possible re-identification of the data.

2. Medical confidential data from a population perspective

However, there is also a parallel consideration, which could be seen as a fundamental socialist goal of solidarity. Patient records in general practice surgeries constitute a unique resource that can provide evidence to help medical researchers improve their understanding of disease, develop potential new treatments and improve patient care. But patient information is both sensitive and private, and the security of personal data must be safeguarded. The Wellcome Trust in 2009 argued that Research has shown that the public are generally supportive of research. Two-thirds of people are likely or certain to allow ‘personal health information’ to be allowed for research – however, there is little public understanding of what this actually means in practice.

As such, the Wellcome Trust therefore believed it was imperative to improve engagement and awareness among the general public:

- there should be a national awareness-raising programme highlighting the importance of using patient records for research, describing the difference between identifiable and non-identifiable data, and explaining the safeguards that will be put in place to protect privacy

- information should also be provided locally through general practices, for example as patients register at a practice, and through posters and leaflets.

The Wellcome Trust argued that, “transparency is essential, and it should be clear that patients can opt out of the use of their identifiable information in research if they wish.” For example, there may be times when it might be useful to know how agents of the NHS themselves behave in making decisions, for example to what extent GPs comply with NICE guidance, and to look for any reasonable deviation from ‘best practice’.

There is a plethora of approaches which could be taken to a ‘train of enquiry’ in how information has handled at GP level. The aim of this Committee is not to go on a ‘fishing expedition’ about all the uses of information at a GP level, for example incentives in making clinical decisions or ‘Nudge’.

The aim of this proposed Committee, for which applications from any interested parties are invited, including from General Practice, academics, doctors in other specialties (especially public health), and patients themselves, is to consider primarily whether patients in the NHS are aware of their ‘rights’ about the information they provide into the NHS, and how the needs for patient confidentiality at an individual and population level can be reconciled from the perspectives of the patient, the researcher, and other interested parties.

Members of the Committee ideally would therefore have to keep themselves familiar with recent policy developments which are relevant, including NHS information governance (including NHS England) and the views of the research councils (including the Wellcome Trust), as well as be aware of the approximate direction of travel of the implementation of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) and EU Data Protection Regulation. It would also be useful if members of the Committee are aware of the current activities of campaigning groups such as Medical Confidential or Liberty, who have tried to raise awareness of this issue previously, and continue to work for the pursuit of that goal.

Thanking you in anticipation.

Useful background reading

http://medconfidential.org/briefings/

http://www.wellcome.ac.uk/About-us/policy/Spotlight-issues/personal-information/gp-records/index.htm

£140 buys private firms data on NHS patients: http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2013/may/17/private-firms-data-hospital-patients (Randeep Ramesh, 17 May 2013, Guardian – @tianran)

GP patient data boosts research: http://www.gponline.com/News/article/1014146/GP-patient-data-boost-research/