Home » Posts tagged 'Alzheimer’s Society'

Tag Archives: Alzheimer’s Society

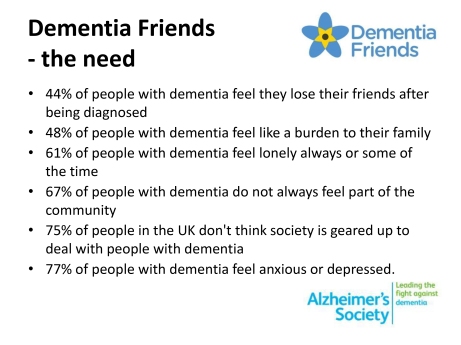

44% of people with dementia feel they lose friends after being diagnosed

Dementia 2012, the first in a series of annual reports from the Alzheimer’s Society, described how well people are living with dementia in 2012 in England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

According to page v of the ‘Executive Summary’. the sample comprised a YouGov poll in December 2011 involving 2070 individuals, but also “drew on existing research and current work”, and polling done by the Society with people in the early stages of dementia in a survey distributed through the Society’s support workers in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. A number for this last group is not stipulated. It is unclear how large the cumulative sample is for each of the key findings, therefore.

This work helps to provide a slide of the key findings underpinning the need for ‘Dementia Friends’, an Alzheimer’s Society and Public Health initiative. For example, one such slide from a presentation available on the internet is:

In detail the findings reported are as follows.

The survey shows that respondents reported losing friends after their diagnosis or being unable to tell them. Nearly half (44%) of respondents said they had either lost most of their friends, some of their friends, or hadn’t been able to tell them.

When asked if they lost friends after their diagnosis of dementia 12% of respondents said yes, most of them, 28% said yes, some of them, and 47% said no.

4% of respondents reported that they haven’t told their friends and 5% didn’t know.

Should we surprised if “44% of people with dementia feel they lose their friends after being diagnosed?”

I remember when I became disabled and went into recovery from severe alcohol dependence syndrome at the same time. Employment was far from my mind. At the time, my friends circle did severely contract, but I should like to think that the friends I am left with are not superficial friends. They are people I suspect would’ve stuck with me through thick and thin anyway.

They are not ‘judgmental’.

Receiving a diagnosis of dementia is not like receiving a criminal conviction. Norman McNamara once joked with me saying he had not been ‘convicted of dementia’ in explaining why he preferred the term ‘GPS trackers’ to ‘GPS tagging’, as a mitigation against wandering.

When I was at the first Alzheimer’s Show in London earlier this year, I met the wife of someone who had received a diagnosis if dementia, and they had not told their friends of their diagnosis for about years.

I suppose that if you have mild memory symptoms as a feature of Alzheimer’s disease, you might not need to tell people that you have a diagnosis, in the same way that you might have an indwelling catheter for multiple sclerosis.

The memory loss may not be immediately obvious.

But this is part of my overall criticism of ‘dementia friendly communities’ – to be ‘friendly’ to people living with dementia, howsoever that is defined, you need to identify such individuals reasonably reliably. I do not buy into this ‘if you see an old biddy have a difficulty, think they might dementia'; particularly since dementia is not confined to older people.

The statistic “44% of people with dementia feel they lose their friends after being diagnosed” becomes even more complicated once you consider various factors which impact upon this finding potentially.

How deep was the friendship in the first place?

And of course what type of dementia? Frontal dementia (behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia) is reasonably common in the younger age group epitomised by progressive behavioural and personality changes.

The thing about this condition, however, is that the person with dementia very often has little or no insight into his change in personality (with the presentation having been noticed by a close friend, or even husband/wife).

Also another feature of conditions affecting the frontal lobes (the part of the brain near the very front of the head) is that such people with problems with the frontal lobe can be extremely bad at making ‘cognitive estimates’.

This was first shown by Prof Tim Shallice and colleagues in the late 1970s: e.g. “how many lamp posts are there on the M1?” “Forty.”

And in the presentation of behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia, it could be obvious to friends that something might be happening as your personality was changing. Therefore, in this scenario, it might be reasonably foreseeable that friends drift away.

Why should people who were friends no longer be bothered? One reason is that ‘they don’t want the hassle’. Maybe staying friends might at later stage involve some sort of requested financial support? Or maybe the former friends don’t want to be involved in ‘uncomfortable discussions’ about dementia?

This is indeed where an initiative to recruit one million ‘Dementia Friends’ through information sessions are useful to dispel the myths and prejudice, as mitigation against stigma and discrimination?

But one of the outcomes which ‘Dementia Friends’ will have to evaluate is whether this project encourages people to ‘befriend’ people with dementia. It is not a mandatory outcome, although people are encouraged to think of this as one of the possible commitments/actions from the information session.

In Japan, befriending has been a successful policy, but the entire care system is much more convincing than our one which has been starved of funds in parallel with Dementia Friends receiving its funding from the Department of Health and Social Care Fund.

But, anyway, would one necessarily expect the friends that one has lost through disclosing a diagnosis of dementia to be matched by friends obtained through ‘Dementia Friends’ in terms of quality? It is of course impossible to answer this question.

This topic is of course closely entwined with the subject of the 2013 report on loneliness. Encouraging participation in wider networks including social networks such as Facebook and Twitter can in the real world help to overcome this.

But with leading politicians continuing to use words such as “horrific”, “evil”, “devastating” in relation to dementia, is it any wonder that, whatever other initiatives, people who have received a diagnosis of dementia are resistant to tell their friends because of the potential reaction?

The statistic “44% of people with dementia feel they lose their friends after being diagnosed” sounds like a typical fundraising slogan, and indeed can be used to justify a national project such as ‘Dementia Friends’.

The proof of the pudding comes in the eating. Will a significantly fewer number feel that they lose friends after being diagnosed (whether they actually lose friends) as a result of “Dementia Friends”? Whilst, as I have explored elsewhere, there is a lot to commend ‘Dementia Friends’, I think it would be wrong to raise this expectation.

And if a significantly fewer number do not feel that they lose friends after being diagnosed, despite “Dementia Friends”, it would be interesting to explore further why. For example, it could be that there are fewer home visits by health professionals, although it is normally argued that ‘anyone who needs a home visit gets one’.

The statistic though acts a useful cover for a quite sinister discussion.

The five core messages of ‘Dementia Friends’ are consistent with the current literature

I first posted this blogpost on my ‘Living well with dementia‘ blog.

“Dementia Friends” is an initiative from the Alzheimer’s Society and Public Health England to raise awareness of the dementias amongst the general public.

Ideally, at the end of a ‘Dementia Friends’ session, each participant will have learned the five key things that everyone should know about dementia, and aspired to turn an understanding into a commitment to action.

In this blogpost, I wish just to discuss a little bit these messages in a way that is interesting. If you’re interested in finding out more about ‘Dementia Friends’, please go to their website. Whatever, I hope you become interested about the dementias, even if you are not already.

I’ve got nothing to do with writing ‘Dementia Friends’, but the following I reckon is a view which would be given by anyone like me who has worked in this academic field for a very long time.

Anyway, I do wish ‘Dementia Friends’ well, and I hope very much you will book yourself into an information session at the first available opportunity.

1. Dementia is not a natural part of aging.

This is an extremely important message.

However, it is known that the greatest known risk factor for dementias overall is increasing age. The majority of people with Alzheimer’s disease, typically manifest as problems in new learning and short term memory are indeed 65 and older.

But Alzheimer’s disease is not just a disease of old age. Up to 5 percent of people with the disease have early onset Alzheimer’s (also known as younger-onset), which often appears when someone is in their 40s or 50s.

[For a further discussion of this statement, please see another blogpost of mine.]

2. It is caused by diseases of the brain.

Prof John Hodges, who did the Foreword to my book, has written the current chapter on dementia in the Oxford Textbook of Medicine. He also supervised my Ph.D. The chapter is here.

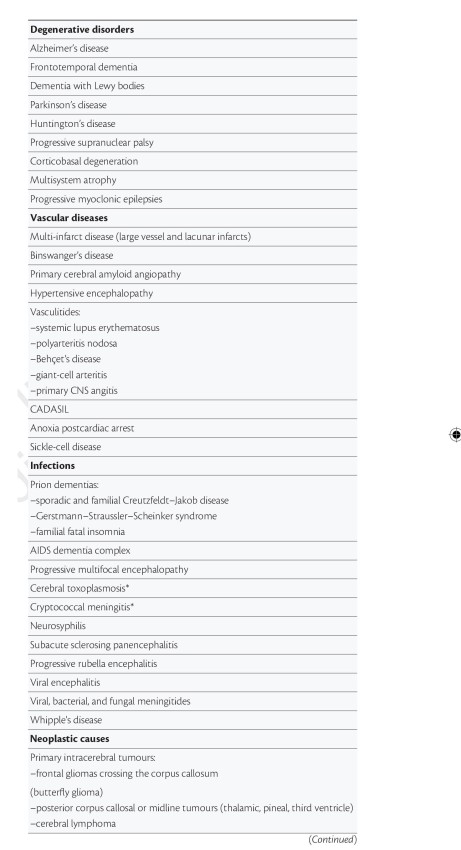

There is a huge number of causes of dementia.

The ‘qualifier’ on this statement is that the diseases affect the brain somehow to produce the problems in thinking. But dementia can occur in the context of conditions which affect the rest of the body too, such as syphilis or systematic lupus erythematosus (“SLE”).

[For a further discussion of this statement, please see another blogpost of mine.]

3. It’s not just about memory loss.

This statement is perhaps ambiguous.

“Not just” might be taken to imply that memory loss should be a part of the presenting symptoms of the dementia.

On the other hand, it might be taken to mean “the presentation can have nothing to do with memory loss”, which is an accurate statement given the current state of play.

John (Hodges) comments:

“The definition of dementia has evolved from one of progressive global intellectual deterioration to a syndrome consisting of progressive impairment in memory and at least one other cognitive deficit (aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, or disturbance in executive function) in the absence of another explanatory central nervous system disorder, depression, or delirium (according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 4th edition (DSM-IV)). Even this recent syndrome concept is becoming inadequate, as researchers and clinicians become more aware of the specific early cognitive profile associated with different dementia syndromes.”

I remember, as part of my own Ph.D. at the University of Cambridge on the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia,virtually all the persons with that specific dementia syndrome, in my study later published in the prestigious journal Brain, had plum-normal memory. In the most up to date global criteria for this syndrome, which should be in the hands of experts, memory is not even part of the six discriminating features of this syndrome as reported.

Exactly the same arguments hold for dementia syndromes which might be picked up through a subtle but robust problem with visual perception (e.g. posterior cortical atrophy) or in language (e.g. semantic dementia or progressive (non-) fluent aphasia, logopenic aphasia.) <- note that this is in the absence of a profound amnestic syndrome (substantial memory problems) as us cognitive neuropsychologists would put it.

[For a further discussion of this statement, please see another blogpost of mine.]

4. It’s possible to live well with dementia.

I of course passionately believe this, or I wouldn’t have written a book on it. It is, apart from all else potentially, the name of the current English dementia strategy.

[For a further discussion of this statement, please see another blogpost of mine.]

5. There is more to the person than the dementia.

This is an extremely important message. I sometimes feel that medics get totally lost in their own clinical diagnoses, backed up by a history, examination and relevant investigations; and they become focused on treating the diagnosis rather than the person with medications. But once you’ve met one person living with dementia, you’ve done exactly that. You’ve met only one person living with dementia. And it is impossible to generalise for what a person with Alzheimer’s disease at a certain age performs like. We need to get round to a more ‘whole person’ concept of the person, in not just recognising physical and mental health but social care and support needs, but realising that a person’s past will influence his present and future; and how he or she interacts with the environment will massively influence that.

[For a further discussion of this statement, please see another blogpost of mine.]

Social stigma, music and living well with dementia

There are 800,000 people living with dementia in the UK, it is thought.

There is no cure at the moment.

“Attitudes are changing. The old stigma is being replaced by the recognition that people with the disease can be helped.”

Later on, John Humphrys spoke this morning to a number of clinicians involved in managing persons with dementia.

The package begins with an initiative called ‘Singing for the brain’.

Singing for the Brain is a service provided by Alzheimer’s Society which uses singing to bring people together in a friendly and stimulating social environment.

The power of music, especially singing, to unlock memories and kickstart the grey matter is an increasingly key feature of dementia care. It seems to reach parts of the damaged brain in ways other forms of communication cannot.

Organisations such as Music for Life, Lost Chord, Golden Oldies and Live Music have also improved accessibility live musicians, both professional and amateur, most of them trained to deal with the special needs of an elderly, memory-impaired audience.

A nice overview of some of these initiatives is given on the Age UK website.

The way in which the brain might do this is indeed interesting.

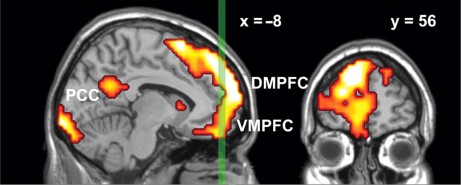

Results from Petra Janata (1999) suggest that the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC) associates music and memories when we experience emotionally salient episodic memories that are triggered by familiar songs from our personal past.

MPFC acted in concert with lateral prefrontal and posterior cortices both in terms of tonality tracking and overall responsiveness to familiar and autobiographically salient songs.

The MPFC is right at the front of the brain.

My interpretation using the “bookcase analogy” of “Dementia Friends” is that while the bookcase representing your memories for events is shaking this bookshelf representing memories triggered by music is unaffected.

It’s virtually the same as the bookcase responsible for sporting memories, in my view of things.

I wonder if ability to reactive sporting memories is correlated with ability to reactivate music memories?

This would explain the efficacy of this approach to living well with dementia.

We not only have to face the reality of the scope of people living with dementia in society.

But as Humphrys articulates in his item.

“Part of it is how society is set up to respond to people who look confused… instead of reacting in a fearful way, we are thinking in terms of how to help such people”, so comments Dr Andrew Crombie from South West London and St George’s Mental Health NHS Trust.

You can listen to the whole of the presentation by John Humphrys – for one week only from the date of this blogpost – on the BBC iPlayer.

Play from about 1 hr 34 mins in on this page.

Social stigma is the extreme disapproval of (or discontent with) a person or group on socially characteristic grounds that are perceived, and serve to distinguish them, from other members of a society. Stigma may then be affixed to such a person, by the greater society, who differs from their cultural norms.

Social stigma can result from the perception (rightly or wrongly) of mental illness, physical disabilities, diseases such as leprosy (see leprosy stigma), illegitimacy, sexual orientation, gender identity, skin tone, education, nationality, ethnicity, ideology, religion (or lack of religion[3][4]) or criminality. Attributes associated with social stigma often vary depending on the geopolitical and corresponding sociopolitical contexts employed by society, in different parts of the world.

According to Goffman in “Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity”, there are three forms of social stigma:

- Overt or external signs, such as scars

- Deviations in personal traits, including forms of medical conditions

- “Tribal stigmas” are traits, imagined or real, of ethnic group, nationality, or of religion that is deemed to be a deviation from the prevailing normative ethnicity, nationality or religion.

Prof Alistair Burns is the National Clinical Lead for dementia for NHS England, and was interviewed by John Humphrys this morning.

“You have highlighted very well in the discussions today and yesterday .. about something which we hear much more of now, and that is: people can live well with dementia. On the interview yesterday, we heard from Linda who felt she was very supported by her friends yesterday, and you said that when you interviewed Grace she felt normal.”

Humphrys was concerned that this was only representative of people living with dementia in the earliest stages.

Burns said, “There are many things that we can do, whatever the stage of dementia.”

“If we look at person-centred care, that is treating people as individuals we’ve heard from ‘Singing for the brain’ and ‘Life Story Work’ can bring people together.”

And have we been doing this successfully thus far?

“It’s fair to say that there has been pockets of excellent work being done around the country.. And one of the things which we must do is to encourage people to do and to learn from areas which are doing well like the example we saw yesterday, and like the example we saw today.”

Humphrys then went on to probe Burns much more about the stigma.

“We know that, from surveys of people for people above the age of 55, dementia is the most feared disease, much more than, say, stroke, heart disease or cancer.”

“There is something about the stigma. What we have seen is a lessening of the stigma, things like ‘Dementia Friends‘, working with schools, and getting ideas into schools.”

Humphrys proposed that it is necessary was to get rid of the idea that there was something about dementia that is “shaming”.

“What you got yesterday from today and yesterday was that people felt normal and supported. But I hear from my own clinic that, experiences where once people receive a diagnosis of dementia, others cross the street.”

“And trying to wrestle that is important.”

My personal experience of an introductory day to ‘Dementia Friends’ Champions

OK it’s not heaven on earth – but Kentish Town London does have some merits I suppose.

To say that I am passionate about the dementia policy in England is an understatement.

Throwing forward, I believe living well with dementia is a crucial policy plank (here’s my article in ‘ETHOS journal’), for which service provision needs a turbo boost through innovation (here’s my article co-written in Health Services Journal).

“Dementia Friends” in reality means rocking up in a venue somewhere near you for about 45 minutes to learn something about the dementias.

Once you sign up on their website, the experience is also backed up by an useful non-public website containing details of training, pre-training materials, and help on how to promote sessions. You can also provide on that website precise details of any ‘Dementia Friends’ information sessions that you run in due course.

I had known of this initiative mainly through Twitter, where I am very active. I find the twitter thread of @DementiaFriends interesting.

Even I’ve been known to get involved in a bit of mass hysteria myself:

I possibly signed up despite of the substantial interest in the media and social media, what psychoanalysts might call an “abreaction”. There’s a large part of me which feels that I do not need 45 minutes on dementia, having studied it for my much of my final undergraduate year at Cambridge, done my Ph.D., written papers such as this (one of which even appears in the current chapter on dementia in the Oxford Textbook of Medicine), written book chapters on it (which as this one which appears in a well known book on younger onset dementia), and even written a book on living well with dementia.

But Prof Alistair Burns is a Dementia Friend – and he’s the clinical lead for dementia in England.

I went out of curiosity to see how Public Health England had joined forces with the Alzheimer’s Society. I must admit that I am intensely loyal to the whole third sector for dementias, including other charities such as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Young Dementia UK, Alzheimer’s BRACE, and Dementia UK.

I have my own particular agendas, such as a proper care system for England, with the provision of specialist nurses such as Admiral Nurses. I think some of the English policy is intensely complicated, best reserved for those who know what they’re talking about – especially people currently living with dementia and all carers including unpaid caregivers.

I personally think the name ‘dementia friendly communities‘ is ill conceived, but the ethos of having inclusive communities, well designed environments and ways of making life easier for people with certain thinking problems (such as memory aids, good signage) highly attractive. It would be unfair in my view for this construct to be engulfed in cynicism, when the fundamental idea is likely to be a meritorious one.

But I don’t think Dementia Friends competes with any of that, and one must be mindful of the gap society had of awareness of dementia.

This gap is still enormous.

And the aim is for people – not just Pharma – to be interested in dementia. These are real people with their own lives, not merely ‘potential subjects for drug trials’ (worthy that the cause of finding an effective symptomatic treatment or even cure might be potentially). But these are people living in the now – take for example the Dementia Alliance International, persons with dementia with beliefs, concerns and expectations of their own like the rest of us.

Only at London Olympia at the “Alzheimer’s Show” [and it is very well I am not a fan of such events which I have previously called "trade shows"], the other week, I presented at London Olympia for my ‘Meet the author session’, arranged on the kind invitation of various people to whom I remain very grateful.

At “The Alzheimer’s Show”, I met within the space of ten minutes a lady newly diagnosed with vascular dementia who did not intend to tell anyone of her diagnosis, and one person married to someone with probable dementia of the Alzheimer type who did not even tell his friends for three years.

It’s a rather badly articulated slogan but the saying ‘no decision made about me without me’ I think is particularly important for dementia.

These are two real (without warning) discussion points from the floor.

“Are people with dementia actually involved with any of the sessions?”

Yes: in fact my pal Chris Roberts (@mason4233) in Wales delivers his Dementia Friends sessions word-perfect for 45 minutes, without telling his audience that he himself lives well with dementia until the very end. Chris tells me this dispels, visibly, preconceived prejudices from his audience members. Chris blogs regularly on his blog, and has written for the ‘Dementia Friends’ blog.

“Why should people with dementia be given special elevated status compared to any other medical condition?”

It’s a difficult one. Some people believe that with dementias people will easily ‘snap out of it’ ‘if they pull themselves together’. This is completely at odds with one of the learning points that dementia is chronic and progressive. And of course people in the real world – viz CCG commissioners – have to decide how much they wish to prioritise dementia ahead of, instead of, etc. other medical conditions such as schizophrenia. But people living with dementia can present with known problems such as forgetting their pin number, and therefore it’s not actually a case about giving people with dementia an ‘elevated status’, but getting them up as individuals to be expected from anyone. Although it’s motherhood and apple pie, it’s very difficult to find, whatever the motive, the intention of dementia friendly high street banking fundamentally objectionable.

Dementia Friends Champions become rehearsed in the programme at one-day sessions across England. What happens is that you watch videos on their website, sign up for a day (where you get to take part in a Dementia Friends session) and then attend the session somewhere close to where you live habitually.

The sessions are run all over England at regular frequency. You sign up for a session, then you get an email quickly afterwards. You go to the meeting.

My meeting started on time. I am physically disabled, so I was grateful for easy access to the venue in Voluntary Action Camden (I could use the lift).

One of the things some of us mean-minded people pick holes in is whether the venue itself might be dementia-friendly. TICK.

I thought so.

The group dynamics worked really well.

My group consisted of interesting people, all ‘realistic’ in their expectations of shifting the Titanic of messaging of negative memes in the media. Many of my group were particularly interested in social equity, fairness and justice, reading between the lines.

I particularly enjoyed speaking with one delegate who is a NHS consultant in psychiatry. We went through pleasant niceties of what he was examined on in his professional membership exams (in his case the difference between schizophrenia and drug-induced psychosis). But he was great to chat to during the day.

I bored him to death with my example of persons with dementia putting numerous teaspoons of sugar in their cups of tea, on rare occasions, due to ‘utilisation behaviour’, a particular predilection for sweet foods since the onset of dementia, or cognitive estimates problem, a very niche area of cognitive neuropsychology for both of us. But this was simply in an activity on making tea where such private chit-chat was irrelevant; the actual session as delivered, on how to make a cup of tea, was far superior than the two hour version I did in a workshop for my MBA in that well known method known to managers: “process mapping“.

The whole day was presented by Hannah Piekarski (@HannahPiekarski), Regional Volunteering Support Officer for the London and South East region for “Dementia Friends.

I’ve sat through more presentations than you’ve had hot dinners, but the standard of the presentation was excellent. Although the presenter clearly had a corpus of statements to make, the presentation was not contrived at all, and the audience had plenty of opportunity to ask questions at points during the day. The presenter evidently knew what she was doing, and was a very good representative of the Dementia Friends programme. She gave her own ‘Dementia Friends’ session which the group of about twenty found faultless.

Hannah even ran a session after the lunch break on what makes a BAD presentation.

Here are my scrappy notes which I took – and please don’t take this to be representative of the actual discussion of what makes a bad presentation which we had in our group.

I SO wish some of my lecturers (including Readers and Professors) had been to Hannah’s session on generic skills in presentations. Whatever you do after ‘Dementia Friends Champions’ day, there’s no doubt that such a session is really useful across various sectors including law and medicine.

You don’t really have to take notes as it’s all fundamentally in their well laid out handbook.

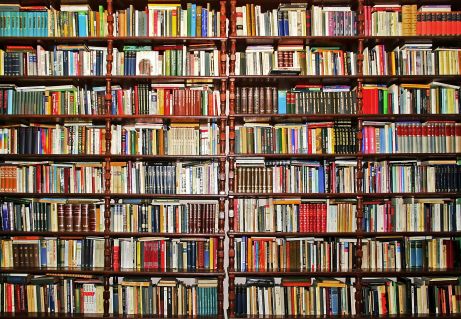

The day was run with the purpose of not giving you tedious crap on how to run a session. But it was furnished with many useful pointers. For example, I learnt of possible venues such as a local library, church halls, and community centres.

Actually, I have in mind to ask Shahban Aziz, CEO of BPP Students, Prof Peter Crisp (Professor of Law at BPP Law School) and Prof Carl Lygo (also Professor of Law at BPP Law School) whether I might run dementia friend sessions at this law school which I attended for my pre-solicitor training. I’ve always had a bit of a discomfort that lawyers are not really given any introduction to dealing with people with dementia, other than professional regulatory considerations or in direct dealings with the law such as mental capacity? I think it’d be great if law students had a basic working knowledge of what dementias are.

It was nice for me to get out of my flat, and meet a range of people. These people ranged from other people in the third sector, for example the Dementia Action Alliance. They bothered to provide free coffee all day, and a free lunch.

And when I tweeted that on my @legalaware Twitter account from my mobile phone in the lunch break (you’re told to turn your mobiles off for the day), I received this smartarse (#lol) remark from one of my 12000 followers immediately.

You’re given a guidebook. You’re not coerced in any way into becoming a Dementia Friend or Dementia Friend Champion. You’re told specifically having done Dementia Friends you can do whatever point of action you wish, even if that includes supporting another charity other than the Alzheimer’s Society.

You are told that the point of the current dementia strategy in England in no way is intended to be political. In support of that claim is that the current strategy has overwhelming cross-party support.

The sessions include information about dementia and how it affects people, as well as the practical things that can be done to help people with dementia live well in their community.

I was given resources to answer people’s questions about dementia and suggest sources of further information and support.

After completing the course Dementia Friends Champions can access resources and tools to help set up and run sessions for people who sign up as Dementia Friends.

These resources include exercises, quiz sheets, bingo sheets, book club ideas and reading suggestions. You’re made very familiar with the content of ‘Dementia Friends’ as they helpfully provide ALL the material on the website when you sign up. They don’t hold any of it back. The point is you go away and run the whole session as ‘Dementia Friends’. Having seen how the 45 minutes works, I have no burning desire to change any of it.

Having said that, there are one or two things I would do differently, hypothetically. The format makes it very clear the presenter is not an expert in dementia or counsellor. I think this actually helps in that an expert possibly could write an hour long essay on each of the five statements for finals, and get truly bogged down in “paralysis by analysis”.

One of the possible features of the ‘Dementia Friends’ session is comparing dementia to a bookcase. This is a well described metaphor, first proposed by Gemma Jones. I have indeed used it to propose a scheme of explaining ‘sporting memories’, an initiative which recently won the Alzheimer’s Society Dementia Friendly Communities national initiatives awards.

Here’s my pal Tony Jameson-Allen picking up his gong.

There’s a bit in the explanation of the bookcase analogy that gets quite technical in fact.

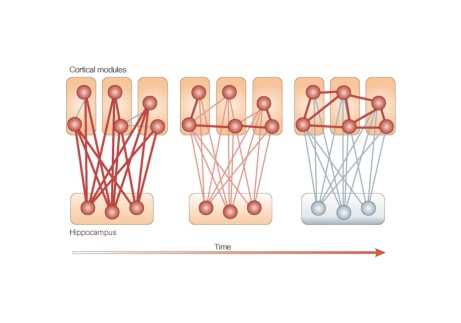

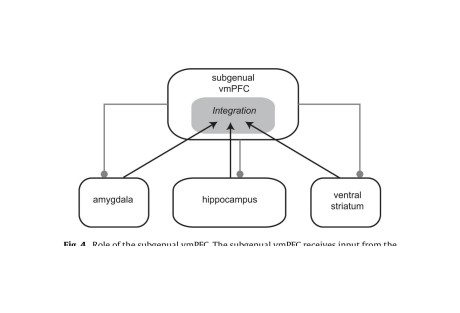

With the presenter of the session having said that he or she is not an expert in dementia or counsellor, it seems counter-intuitive to me that there is an explanation of the organisation of memory using two highly technical locations in the brain, the hippocampus and amygdala. But things like that are not a ‘deal maker’ or ‘deal breaker’ for me. There’s an excellent video of a presentation of the bookcase analogy by Natalie Rodriguez floating around, in fact, but we were all encouraged to be explain the analogy ‘live’ in our sessions, ‘rather than playing the DVD’.

I have absolutely no problem with the material being pre-scripted. I used to supervise neuroscience and experimental psychology for various colleges at Cambridge between 1997 and 2000 inclusive, and, whilst the guidance for teaching that was not as intense, it’s fair for me to mention that supervisors knew exactly what they had to cover for their students to achieve at least an upper second in finals.

Dementia Friends Champions, like me, are then be encouraged to run Dementia Friends sessions at lunch clubs, educational institutions and other community groups, but it could also include ideas such as arranging a meeting to talk with a small group of friends.

I intend to run five sessions to achieve about 100 further dementia friends. I conceptually find targets anywhere quite odious, and see exactly where this ambition has come from (Japan). On the other hand, nobody is a clairvoyant. The fact the number exists at all (aiming for March 2015) is a testament that this programme is being taken seriously. Had the number been set at 400, then we would all have said ‘job done’ some time ago.

I am actually, rather, amazed that somebody somewhere has signed off for a national programme to invite ordinary members of the public to attend free of charge a day on delivering the Dementia Friends programme, with nice company, and of course that free coffee and lunch.

I am also amazed that the actual substrate of the information sessions for ‘Dementia Friends’ is being offered to the member of the public free of charge, and it effectively has been paid for by Government.

The operational delivery of ‘Dementia Friends Champions’ day was totally faultless from start to finish. Even though I have nothing to do with their output, the Alzheimer’s Society here in England have done a brilliant job with it.

And finally I’ve tended to query whether it can be a genuine ‘social movement’ which so much resource allocation.

But people are genuinely interested in the programme, as these tweets to me demonstrate, I feel:

Look.

There are all sorts of things which do irritate me such as the issue that any dementia awareness should observe boundaries. For example, there are also many global ‘Purple Angels’ motivated by the leadership of Norman McNamara (@norrms), himself living with dementia of diffuse Lewy Body Type.

Here’s their brand new website. Norman is a very good friend of mine, so I’m bound to be loyal to him.

In a different jurisdiction – Australia – a close friend of mine, Kate Swaffer (@KateSwaffer), blogs daily on her busy life living with dementia, which includes being an advocate, travelling, cuisine (Kate is very experienced in sophisticated cooking), a background in healthcare, a student at the University of Wollongong, and what’s it like to live with dementia after being given the diagnosis. Her blog is here.

Chris, Norrms and Kate are all quite different – like the rest of the population – getting on with their lives. And as the very famous adage goes, once you’ve met one person living with dementia, you’ve done exactly done. You’ve met only one person with dementia.

And there’s clearly a huge amount to be done. Also at the Alzheimer Show one carer reported a person with dementia being ‘lost to the system’, completely unknown to anyone for care for three years.

I had a huge volume of concerns about this initiative, and I’m no pushover as far as being ‘in with the in-gang’ is concerned. But I strongly recommend you park your misgivings and go there wanting to be a part of a “change”.

I went on the day after the passing away of the incredible Dr Maya Angelou.

As she said, “If you don’t like something, change it. If you can’t change it, change your attitude.”

Living well with corporate capture. What is the future of the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge?

“Citizens have become consumers with status proportional to purchasing power, and former public spaces have been enclosed and transformed into private malls for shopping as recreation or “therapy.” Step by step, private companies, dedicated to enriching their owners, take over the core functions of the state. This process, which has profound implications for health policy, is promoted by politicians proclaiming an “ideology” of shrinking the state to the absolute minimum. These politicians envisage replacing almost all public service provision through outsourcing and other forms of privatisation such as “right to provide” management buyouts. This ambition extends far beyond health and social care, reaching even to policing and the armed forces.”

And so write Jennifer Mindell, Lucy Reynolds and Martin McKee recently about ‘corporate capture’ in the British Medical Journal.

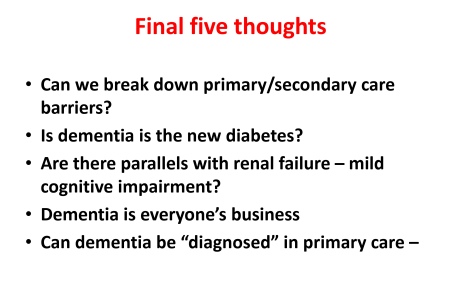

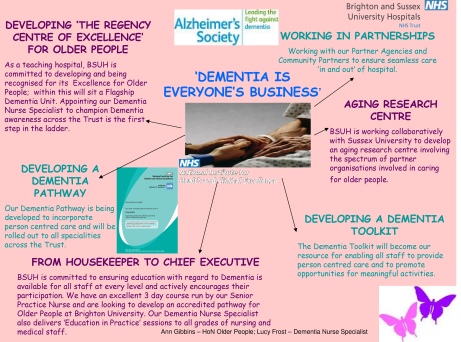

Alistair Burns, England’s clinical lead on dementia, recently concluded a presentation on the clinical network for London with the following slide:

Alistair clearly does not mean ‘Dementia is everyone’s business’ in the “corporate capture” sense. Instead, he is presumably drawing attention to initiatives such as Brighton and Sussex Medical School’s initiative to promote dementia awareness at all levels of an organisation (and society).

The comparison with diabetes is for me interesting in that I think of living well with diabetes, post diagnosis, as conceptually similar to living well with dementia, in the sense that living well with a long term condition is a way of life. And with good control, it’s possible for some people to avoid hospital, becoming patients, when care in the community would be preferred for a number of clinical reasons. Where I feel the comparison falls flat is that I do not think that it is possible to measure outcomes for living well with dementia easily. Sure, I have writen on metrics used to measure living well with dementia, drawing on the work of Sube Banerjee, Alistair’s predecessor. It might be possible to correlate good control with a blood test value such as the HBA1c, and it steers the reward mechanism of the NHS for rewarding clinicians for failure of management (e.g. laser treatment in the eye, foot amputation, renal dialysis), but the comparison needs some clinical expertise to be pulled off properly. The issue of breaking down ‘barriers’ between primary and secondary care is an urgent issue, and ‘whole person care’ or ‘integrated care’ may or may not help to facilitate that. But a future government must not get too enmeshed in sloganising if it means forgetting basic requirements of foot soldiers on the ground, such as specialist dementia nurses including Dementia UK’s ‘Admiral nurses’.

But the question of who gives the correct diagnosis of dementia, or even verifies it, won’t go away.

Having done Dementia Friends myself, a Public Health England the Alzheimer’s Society joint initiative, I feel the initiative is extremely well executed from an operational level. I think it’s pushing it for a member of the public to think that an old and doddering lady crossing the lady might have dementia and requires help, as medicalising ageing into dementia is a dangerous route to take. The £2.4 million programme is funded by the Social Fund and the Department of Health. Public Health England are planning to undertake an evaluation of the Dementia Friends Campaign launched on 7 May 2014, which will include tracking data and prevention message testing.

There are a number of important clinical points here. There are crucial questions as to whether persons themselves with a possible diagnosis, friends and/or families themselves want a diagnosis of dementia. A diagnosis of dementia in anyone’s book is a life-changing event. The concerns of the medical profession have been effectively rehearsed. Notwithstanding, the ambition that, by 2015, two thirds of the estimated number of people with dementia should have a diagnosis, with appropriate post diagnostic support has been agreed with NHS England. To support GPs and other primary care staff, a Dementia Roadmap web-based tool has been commissioned by the Department of Health from the Royal College of General Practitioners. The roadmap has now been officially launched, and will provide a framework that local areas can use to provide local information about dementia from health, social care and the third sector to assist primary care staff to more effectively support patients, families and carers from the time of diagnosis and beyond. Feedback from relevant stakeholders will be most interesting.

People with dementia need to be followed up across a period of time for a diagnosis of dementia to be reliably made, and ‘in the right hands’, i.e. of a specialist dementia service. Whilst NHS England are working with those areas with the longest waits, with the aim of ensuring that anyone with suspected dementia will not have an excessive wait for a timely assessment, there has to be monitoring of who does that timely assessment and whether it produces an accurate result. At an extreme example, clinical diagnoses of rarer dementias, particularly younger onset, can only be done effectively by senior physicians with reference to two clinical histories, two clinical examinations, neuroimaging (e.g. CT, MRI, or even fMRI or SPECT), lumbar puncture/cerebrospinal fluid (if not contraindicated), cognitive psychology, EEG, or even – extremely rarely – a brain biopsy. But this would be to propose an Aunt Sally argument – many possible cases of dementia can be tackled by primary care with appropriate testing perhaps in the future, and certainly adequate resources will need to be put into primary care for training of the workforce. Or else, it is literally a ‘something for nothing’ approach. Some people have ‘mild cognitive impairment’ instead, and will never progress to dementia.There are 149,186 dementia friends currently. This number is rapidly increasing. The goal is one million.Furthermore, there are many people given a diagnosis of dementia while alive who never have it post mortem. And the diagnosis can only be definitively made post mortem. Seth Love’s brilliant research (and he is an ‘Ambassador’ to the Alzheimer’s BRACE charity) is a testament to this. Anyway, NHS England and the Department of Health are working with the Royal College of Psychiatrists to encourage more Memory Services to become accredited.

And when is screening not officially screening? This continues to require definition in England’s policy. The original Wilson and Jungner (1968) principles have appear to have become muffled in translation. The CQUIN has led to over 4,000 referrals a month, but this will only contribute to improving diagnosis rates for dementia if this is not producing a tidal wave of false positives. For quarter 3 2013/14, 83% of admitted patients were initially assessed for potential dementia. Of those assessed and found as potentially having dementia, 89% were further assessed. And of those diagnosed as potentially having dementia, 86% were referred on to specialist services. But we do need the final figure. This policy plank for me will also go back to the issue of whether policy is putting sufficient resources into the diagnostic process and beyond. Stories of people being landed with a diagnosis out of nowhere and given not much further information than an information pack are all too common. A well designed system would have counselling before the diagnosis, during the diagnosis, and after the diagnosis.

Ideally, an appointed advisor would then see to continuity of care, allowing persons with dementia to be able to feel confident about telling their diagnosis to friends and/or family. The advisor would ideally then give impartial advice on social determinants of health, such as housing or education. Policy may be slowly moving in this direction. In April 2014 NHS England published a new Dementia Directed Enhanced Service (DES) for take up by GPs to reward practices for facilitating timely diagnosis and support for people with dementia. Patients who have a diagnosis of dementia will be offered an extended appointment to develop a care plan. The care planning discussion will focus on their physical and mental health and social needs, which will include referral and signposting to local support services. From 10 signatories in March 2012, to date, there are now 173 organisations representing nearly 3,000 care services committed to delivering high quality, personalised care to people with dementia and their carers.

But all this requires money and skill. There is no quick fix.

The areas of action for the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge are: dementia friendly communities, health and care and improving research.

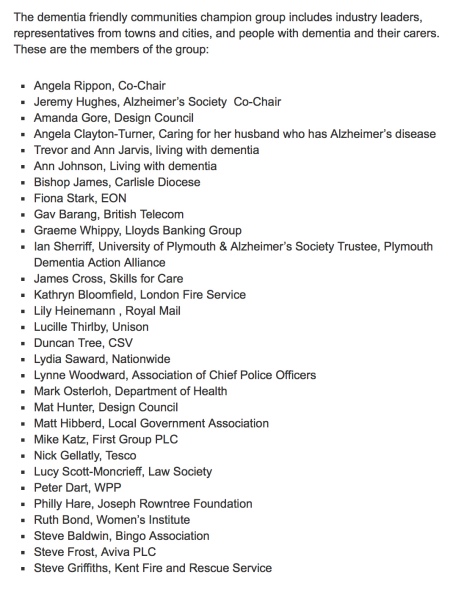

In November 2012, The Secretary of State for Health announced a £50 million dementia-friendly environments capital investment fund to support the NHS and social care to create dementia-friendly environments. The term ‘dementia friendly communities’ is intrinsically difficult, for reasons I have previously tried to introduce. A concern must be the ideology behind the introduction of this policy in this jurisdiction. The emphasis has been very much on making businesses ‘business friendly’, which is of a plausible raison d’être in itself. This, arguably, is reflected in the list of chief stakeholders of the dementia friendly communities champion group.

It happens to fit very nicely with the Big Society and the ‘Nudge’ narrative of the current government. But it sits uneasy with the idea that it is in fact a manifestation of a small state which bears little responsibility apart from overseeing at an arm’s length a free market. The critical test is whether this policy plank might have improved NHS care. 42 NHS and 74 Social Care National pilot schemes were approved in June 2013 as national pilots. Most of the projects have now been completed, and they will be evaluated by a team of researchers at Loughborough University over the coming months. The evaluation will provide knowledge and evidence about those aspects of the physical care environment which can be used to provide improved care provision for people with dementia, their families and carers. But the policy has had some very exciting successes: for example the ‘Sporting Memories Network’, an approach based on the neural re-activation of sporting autobiographical memories, recently scooped top prize for national initiative in the Alzheimer’s Society Dementia Friendly Communities Awards 2014.

And meanwhile, the care system in England is on its knees. Stories of drastic underfunding of the care system are extremely common now. An army of millions of unpaid family carers are left propping up a system which barely works. There appears to be little interest in guiding these people, with psychological, financial and/or legal burdens of their own, to reassure them that all their hard work is delivering an extraordinary level of person-centred care.

But this for me was an inevitable consequence of ‘corporate capture’. The G8 World Dementia Council does not have any representatives of people with dementia or carers.

That is why ‘Living well with dementia’ is an important research strand, and hopefully one which Prof Martin Rossor and colleagues at NIHR for dementia research will give due attention to in due course. But all too readily research into innovations, ambient assisted living, design of the ward, dementia friendly communities, assistive technology, and advocacy play second fiddle to the endless song of Big Pharma, touting how a ‘cure’ for dementia is just around the corner. Yet again.

So what’s the solution?

The answer lies, I feel, in particularly what happens in the next year and beyond.

The Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia was developed as a successor to the National Dementia Strategy, with the challenge of delivering major improvements in dementia care, support and research. It runs until March 2015. Preparatory work to produce a successor to the Challenge from the Department of Health (of England) is now underway in order that all the stakeholders can fully understand progress so far and identify those areas where more needs to be done. The Department of Health have therefore commissioned an independent assessment of progress on dementia since 2009.

There are a number of other important pieces of work that are underway, which will provide information and evidence about progress and gaps. For example, according to the Department of Health, the All Party Parliamentary Group on Dementia chaired by The Baroness Sally Greengross OBE are producing a report focused on the National Dementia Strategy, and the Alzheimer’s Society has commissioned Deloitte to assess progress and in the autumn will be publishing new prevalence data. Indeed the corporate entity known as Deloitte Access Australia (a different set of management consultants in the private sector) produced in September 2011 a report on prevalence of dementia estimates in Australia. Deloitte themselves have an impressive, varied output regarding dementia. But of course they are not interested in dementia solely. “Deloitte” is the brand under which tens of thousands of dedicated professionals in independent firms throughout the world collaborate to provide audit, consulting, financial advisory, risk management, tax, and related services to select clients.

But also it appears that the Alzheimer’s Society, working with NHS England, has commissioned the London School of Economics to undertake a review into the accuracy of dementia prevalence data. The updated data is expected to be published in Autumn 2014. Apparently, once all this work has been concluded a decision will be made on the focus and aims of the successor to the PM’s challenge.

The current Coalition government has been much criticised in parts of the non-mainstream media for the representation of corporate private interests in the Health and Social Care Act (2012).

I believe people who are interested in dementia, including persons with dementia, caseworkers and academics, should make their opinions known to the APPG in a structured articulate way in time. I think not much will be achieved through the pages of the medical newspapers. And only time will tell whether the new dementia strategy will emerge in time before the next general election in England, to be held on May 7th 2015. However, even the most ardent critics will ultimately. The present Government should be congratulated for having made such a massive effort in educating the country about dementia, which is a necessary first step towards overcoming stigma and discrimination. The Alzheimer’s Society has impressively delivered its part of it, it appears, but future policy will benefit from much more ‘aggressive inclusion’ of other larger stakeholders (e.g. the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Dementia UK) and smaller stakeholders.

It could be a case of: all change please. But a huge amount has been done.

An explanation for sporting memories can be found in the “bookcase analogy”, featured in the ‘Dementia Friends’ initiative

One amazing phenomenon is that it’s possible to stimulate memories in people living with dementia by the presentation of football memorabilia, as described by Rachel Doeg here.

The transformation is quite remarkable: “reeling off expert knowledge and sharing collective memories that bring laughter and camaraderie to the group,and a boost to their self-esteem.”

“Bill’s story” is another brilliant example from “Sporting Memories“:

“Sporting memories” was established to explore the stimulation of living well in people with dementia, through conversations and reminiscence.

The Dementia Friends programme supports people who want better to understand all the implications of the condition. Last week saw celebrities and people living with dementia teaming up with the Dementia Friends Campaign to encourage even more of us to sign up. It is hoped that one million will be recruited by 2015.

One of the ‘talking points’ in ‘Dementia Friends’ might “the bookshelf analogy of Alzheimer’s Disease”.

This video taken from the “Dementia Partnerships” website shows Natalie Rodriguez, Dementia Friends Champion, using this analogy to describe how dementia may affect a person.

This simple explanation, orginally devised by Dr Gemma Jones, can be helpful for Dementia Friends Champions to explain dementia to others. A full description of it is given here.

The usual explanation of the early features of Alzheimer’s disease using the ‘bookcase analogy’

In this analogy, the brain has a number of ‘bookcases’ which store a number of memories, such as memory for events about the world, memory for sensory associations, or emotional memory, to name but a few.

Let’s now focus on the memory for events about the world bookcase.

The top shelves contain more recent memories, and, as you go down the bookshelf, more old memories are stored.

When you jog this memory shelf, the books on the top may wiggle a bit, causing minor forgetfulness about recent events, such as where you put your keys.

As you jog it a bit more, the books on the top shelf may fall off altogether, making it impossible to learn new stuff and retain stuff for a short period of time.

The bottom shelves of the short memory bookcase remain unperturbed.

The jogging of this memory for events about the world bookcase is equivalent to what happens in early Alzheimer’s disease, when something goes wrong in the top shelves only.

The top shelves correspond to the hippocampus part of the brain – it’s near the ear, and so called as it looks like a sea-horse. That’s where disease tends to happen first in Alzheimer’s disease.

So you can see what happens overall. In the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, a common cause of dementia, problems in short-term memory for events about the world can be profound, while long-term memories around the world are relatively infact.

As they correspond to different bookcases altogether, sensory and emotional memory are left relatively intact.

How the ‘bookcase analogy’ can be used to explain the phenomenon of “sporting memories”

I haven’t mentioned another bookcase altogether. This is a memory of events about yourself – so-called “autobiographical memory” – and this is held in a part of the brain by the eye (the ventromedial subgenual cortex).

There’s a very good review from a major scientific journal, called “The role of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in memory consolidation” by Ingrid L.C. Nieuwenhuisa and Atsuko Takashima published recently in 2011.

Autobiographical memories, such as sporting matches, are first formed in the hipppocampus, and they then get dispatched to a totally different part of the brain, the ventromedial/subgenual cortex as these memories become “consolidated”.

In other words, books can come from the events around the world bookcase, but while this is wobbling the autobiographical bookshelf is unscathed.

The crazy thing though is that the intact ventromedial prefrontal cortex is also connected with the intact amygdala in early Alzheimer’s disease, which means the autobiographical bookcase can arouse emotional memories in that bookshelf.

Sporting memories and “dementia friendly communities”

It is also a nominee under the category “National Initiative” in the Alzheimer’s Society first Dementia Friendly Awards, sponsored by Lloyds Banking Group and supported by The Telegraph, the winners of which will be announced on May 20. The awards recognise communities, organisations and individuals that have helped to make their area more dementia-friendly.

The awards shortlist is at alzheimers.org.uk/dementiafriendlyawards

2 Qns in #pmqs on dementia, but 2 As on ‘Dementia Friends’ not living well with dementia

Dementia was mentioned twice today in Prime Minister’s Questions.

There was a ‘big announcement’ today from the Alzheimer’s Society which could have been used to convey the meaning of how people living with dementia could be encouraged to live well in productive lives.

As part of this publicity, Terry Pratchett was pictured holding up a placade saying, “It’s possible to live well with dementia and write bestsellers “like what I do””.

An Independent article carries the main thrust of this message:

“Up to £1.6 billion a year is lost to English business every year, as employees take time off or leave work altogether to provide at-home care for elderly relatives, according to the report, compiled by the Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR).”

“On top of those that stop working, another 66,000 are making adjustments to their work arrangements, such as committing to fewer hours or working from home.”

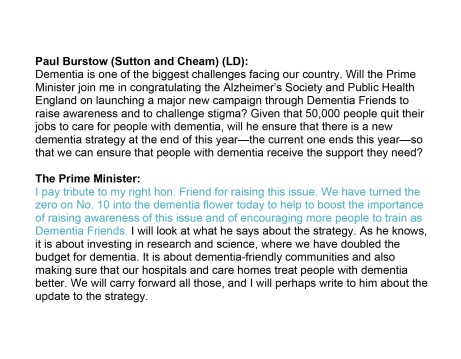

Paul Burstow MP brought up the first question specifically around this initiative.

Here is the Question/Answer exchange as described in Hansard:

The answer fails spectacularly to address the issue of living well with dementia, but is a brilliant marketing shill for ‘Dementia Friends’.

There’s no attempt to include any other charity working in dementia.

It doesn’t mention the C word either – Carers.

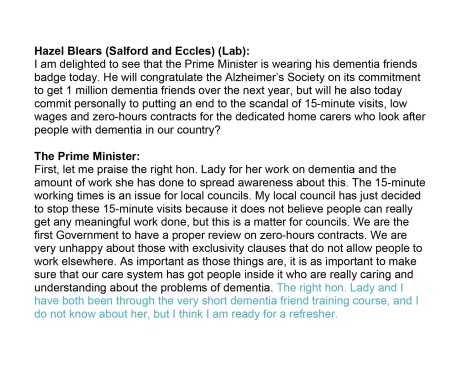

And then it was left up to Hazel Blears MP to provide another question on dementia.

This time it’s a bit different.

There’s no answer on how zero hours contracts cannot specifically in the care system promote living well for either carers (including unpaid careworkers) or persons with dementia.

But it’s exactly the same otherwise.

A brilliant marketing shill for Dementia Friends, and no mention of any other charity working on dementia.

Quite incredibly here, Cameron produces an answer on ‘caring’ in dementia without mentioning carers or careworkers.

With Ed Miliband, Ed Miliband and David Cameron all wearing their ‘Dementia Friends’ badges, is it any wonder you never hear about Dementia UK’s Admiral Nurses any more?

There is undoubtedly a rôle for all players in a plural vibrant community, but this should never have been allowed to become an ‘either’/’or’ situation.

Did the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge park a ‘National Care Service’ for good?

I’m still unclear where and when the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge came about.

The lack of a clear audit trail for the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge

I know that it was launched in March 2012.

“Dementia” is not mentioned in the Conservative Party Manifesto for the general election of 2010. It is however mentioned in the Coalition Agreement, with broadly the same wording as the Liberal Democrat manifesto 2010, but that still doesn’t explain how this became the “Prime Minister’s Challenge”.

In summary, the one line in the Coalition Agreement is drafted as follows:

“We will prioritise dementia research within the health research and development budget”

But still no specific mention of that “Challenge”.

The distortion effect of the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge

The Dementia Challenge prioritises the Alzheimer’s Society, and it is clear that other charities, such as Dementia UK (which is experiencing threats of its own to its superb ‘Admiral nurses’ scheme) trying to plough on regardless.

Indeed, many supported the fundraising for Dementia UK only this morning in the London Marathon too.

There is no official cross-party consensus on the “Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge”, though individual Labour MPs support the activities of “Dementia Friends”.

The market dominance of the Alzheimer’s Society for ‘Dementia Friends’ compared to other charities does not seem to have been arrived at particularly democratically either. There is no conceivable reason why other big players, such as “Dementia UK” or the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, were excluded from this friendship initiative.

Ironically, Japan upon which befriending is modelled is not ashamed of its care service.

It is palpably unacceptable if people are ‘more aware of dementia’ without a concominant investment in specialist memory clinics, or care and support services.

Genuine concerns from stakeholders involved with dementia care

It is clear amongst my followers on Twitter that the nature of this “Challenge” is causing considerable unease.

Agreed “@Ermintrude2: @Cleverestcookie @legalaware exactly. it isn’t dementia thats the challenge. It’s the health and social care system.”

— Liz Wilson (@aphidcatcher) April 13, 2014

Concidentally I was reminded of this this morning:

« Be wary of the man who urges an action in which he himself incurs no risk. » Seneca http://t.co/0PgxlIVbrF — Philosophers quotes (@philo_quotes) April 13, 2014

But there are now some very serious questions about this policy, particularly from the ‘zero sum gain’ effect it has had knock-on in other areas of dementia policy.

@Bexmoxon @Cleverestcookie @Ermintrude2 @legalaware people living dementia, their carers, practitioners etc views taken piecemeal as per

— Mark Barlow (@mark_b33) April 13, 2014

@Ermintrude2 @legalaware @mark_b33 IME they often don’t talk to the right people. Not the people with current links to actually what’s doing — Cathy Cooke (@Cleverestcookie) April 13, 2014

When @Ermintrude2 looked into this at the time, the response was a bit confused.

@mark_b33 @legalaware I think they are looking at the wrong problems. I was told by a DH official that agenda set by talking to..

— Ermintrude (@Ermintrude2) April 13, 2014

@mark_b33 @legalaware “the great and the good” (her words). That is EXACTLY the challenge that needs tackling. Govt talking to same people. — Ermintrude (@Ermintrude2) April 13, 2014

And indeed Ermintrude has penned some thoughts at the time on this high impact blog.

What has happened to social care in the name of ‘improvement’, I agree, is very alarming.

@legalaware The Dementia Challenge – smoke and mirrors. Nice platform for government to make people think they are doing stuff..

— Ermintrude (@Ermintrude2) April 13, 2014

@legalaware seeing how utterly offensive it is for govt to make these ‘improvement’ statements or pretend they care when they are.. — Ermintrude (@Ermintrude2) April 13, 2014

But we do know full-well about the ‘democratic deficit’.

False pledges and threats, and unfulfilled promises

The general public were unaware that a 493 Act of parliament called the ‘Health and Social Care Act’ would be sprung on them, with a £3 bn top-down reorganisation.

But this was Lansley’s “emergency conference” on Labour’s “secret death tax” in February 2010.

A number of views were expressed at the time, including the need for better care from the Alzheimer’s Society at the time under a different CEO.

The full thrust of ‘Dementia Friends’ is a total change of mood music from February 2010’s concerns of the Alzheimer’s Society reported here:

“Care and treatment for sufferers of dementia should be at the heart of the general election campaign, the Alzheimer’s Society charity has said.”

Where has the Society been in campaigning on swingeing cuts in social care?

Also, in February 2010, Gordon Brown’s speech at the King’s Fund was reported, where Brown made a significant pledge.

“Mr Brown also announced that the government’s planned reforms to community and primary care health services also included a commitment to provide dedicated “one-to-one”nursing for all cancer patients in their own homes, over the next five years.”

We do know that the NHS has been persevering with this programme with ‘efficiency savings’.

In October 2012, it was reported that nearly £3bn was indeed returned to the Treasury, and it is unclear how, if it at all, it was returned to front line care.

So it’s possible that Brown’s plan, the subject of a hate campaign at the time from the Tory press, might have worked in fact.

Dilnot

In 2010 Andrew Dilnot had been tasked by the then government to propose a solution to the crisis in social care.

The response was from February 2013, after the top-down reorganisation.

“Mr Dilnot suggested a cap on how much anyone would be required to pay for their care costs over the course of a lifetime, suggesting a ceiling of between £25,000 and £50,000 (in 2010/11 prices). Beyond this point, the state would take on responsibility for the majority of the bill.

The Government today announced that from 2017 it intends to establish a cap of £75,000 in 2017 prices which, according to Mr Dilnot’s calculations, equates to approximately £61,000 in the 2010/11 prices (the basis of his report). If we’re to make a claim about the extent to which the Government has ‘watered down’ Mr Dilnot’s proposal, it’s crucial that we account for this inflationary effect.”

Resurrection of the ‘National Care Service’ by Andy Burnham MP yesterday, Shadow Secretary of State for Health

This issue may have to be revisited at some stage. Andy Burnham MP yesterday in the Bermondsey Village Hall, without much press present, mooted the idea of how a social care service could be established on the founding principles of the NHS, and would be a significant departure from the piecemeal 15-minute slot carers.

Burnham stated that care provided by inexperienced staff on zero-hour contracts was a problem.

An experienced member of the audience highlighted the phenomenal work done by unpaid family caregivers particularly for dementia.

The topic of a compulsory state insurance is interesting.

In his classic article, Kenneth Arrow (1963) argues that, where markets fail, other institutions may arise to mitigate the resulting problems: ‘the failure of the market to insure against uncertainties has created many social institutions in which the usual assumptions of the market are to some extent contradicted’ (p. 967).

Rationale for this method of funding

A great advantage of ‘social insurance’ is, because membership is generally compulsory, it is possible (though not essential) to break the link between premium and individual risk.

There might be other important aspects. For example, both employers and employees pay contributions. Also, there might be Government support for those who are unable to pay goes through the insurance fund.

The philosopher John Rawls (1972) argues that in a just society the rules are made by people who do not know where they will end up in that society, that is, behind what he called the “Veil of Ignorance”.

Insurance can be interpreted as an example of solidarity behind the Veil of Ignorance: a person who joins a risk pool does not know in advance whether or not he will suffer a loss and hence have to make a claim. Insurance thus has moral appeal.

Ultimately there is a problem as to what type of care might be covered.

Does the policy cover only residential care, or also domiciliary care; is a person entitled to residential care on the basis of general infirmity or only if he or she has clearly-defined, specific ailments?

In the Dilnot recommendations, the cap on care payments did not include the “hotel costs” that a care home will charge. In other words, people in residential care will still need to pay (at the Dilnot report’s estimate) between £7,000 and £10,000 per year to fund their accommodation and living expenses.

Furthermore, how will the answers to these questions change with advances over the years with changes in the actual prevalence of dementia, or in the implementation of ever increasingly sophisticated medical technology?

It has been proposed (Lloyd 2008) that long-term care could be financed via social insurance, with the premium paid as a lump sum either at age 65 or out of a person’s estate. The idea behind this proposal is twofol.

Firstly, as a person gets older, the range of uncertainty about the probability of needing long-term care becomes smaller.

Secondly, if a person can buy insurance for a single premium payable out of his or her estate, the cost of long-term care does not impinge on his or her living standard during working life or in retirement, but can frequently be taken from housing wealth.

Development of social health insurance systems have normally been in response to concerns that inadequate resources were mobilised to support access to health services.

The continuing swingeing cuts in social care

And these cuts have continued: this report is from March 12 2014,

“An analysis by Mind found that the number of adults with mental health needs who received social care support has fallen by at least 30,000 since 2005, a drop of 21%. Cuts to local authority social care budgets – the majority of which have hit since 2009 – have left a funding shortfall for care of up to £260 million, the charity said.”

Since there is no simple answer to the question of how much is the appropriate level of support, the issue of adequacy is best thought of as being a level that is considered appropriate in the country given its total resources, preferences and other development priorities.

And where are people from charities campaigning on this issue?

This issue of course was not considered at all in the G8 Dementia Summit, which focused on more monies for personalised medicine, genetic and molecular biology research, in response to concerns from an “ailing industry”.

Conclusion

I am actually truly disgusted at this unholy mess.

References

Arrow, Kenneth F. (1963), ‘Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical Care’, American Economic Review, 53: 941–73; repr. in Cooper and Culyer (1973: 13–48), Diamond and Rothschild (1978: 348–75), and Barr (2001b: Vol. I, 275-307).

Lloyd, James (2008), Funding Long-term Care – The Building Blocks of Reform, London: