Home » Posts tagged 'Allyson Pollock'

Tag Archives: Allyson Pollock

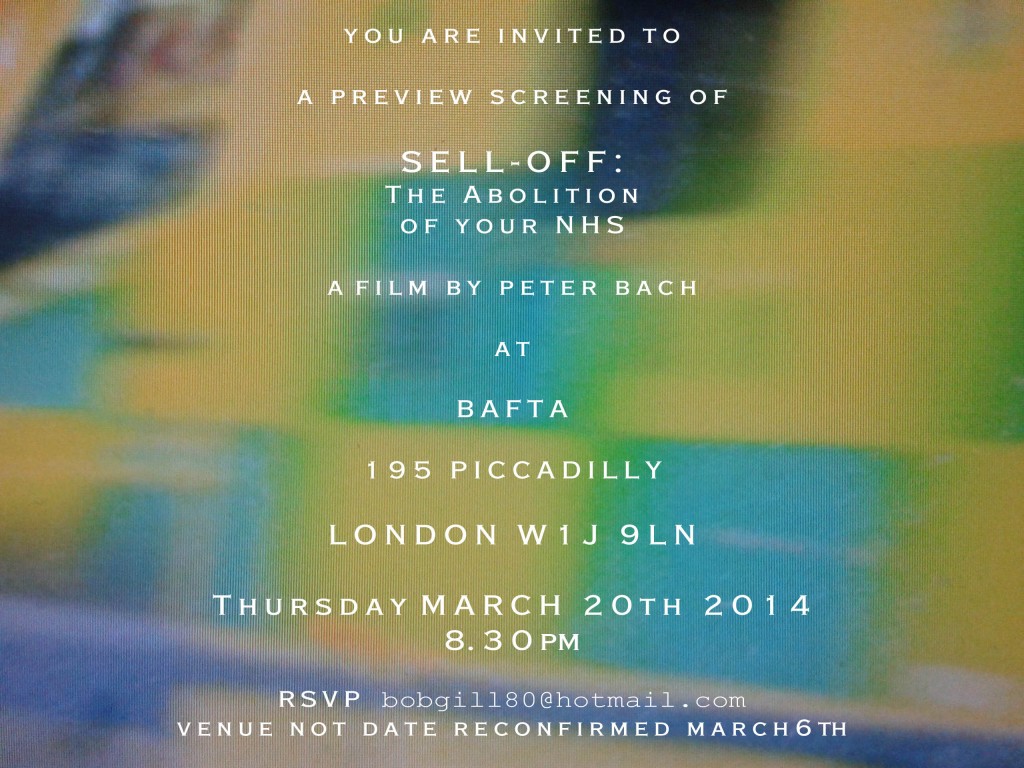

Review: A film by Peter Bach called “Sell off: the abolition of your NHS”

For health reasons, I don’t drink. After a six week coma due to meningitis at the Royal Free, which left me disabled, I have a massively personal reason why I am grateful to the NHS.

This one event taught me that anything can happen at any time. Last night, I went along to a private viewing of “Sell-off: The abolition of your NHS” at the BAFTA in Piccadilly. Not having drunk for alcohol for seven years, I don’t feel any particular urge to drink. In fact, I quite liked the atmosphere of their bar in the complete absence of alcohol. I quite like diet Coke.

The bar made me think of New York in fact in a brief period of escapism from a wet and miserable evening in March in Central London.

While I was sat thinking about how unusual it was for me to go to bars these days, I heard a voice I recognised. Then I suddenly twigged who it was – Tamasin Cave, Director of Spinwatch, was talking with someone about the “Lobbying Tour”. I said as politely as I could to her that the YouTube video of her tour is very famous.

“Famous for a certain group of people perhaps!”, she replied.

Peter Bach’s film, which is currently in an uncut stage, is exquisitely done. It covers all the points you’d expect in a documentary about a piece of legislation which was railroaded in without meaningful discussion. The frames of those people interviewed flow nicely, and the resulting narrative is coherent. I know this particular narrative extremely well, but there were some points for seasoned viewers like me too.

The views on the NHS captured in Bach’s film impressively don’t sound like one spiteful rant, though, which is the really clever aspect of the film. The film is possibly best described as a clear fly-on-the-wall documentary where patients and doctors clearly feel utterly disenfranchised from the NHS. This is of course in total contrast to the humanistic foundations of the NHS in the 1940s.

Peter Bach, the filmmaker, talks about how he went to a basement in Earls Court, to say how “he was bombarded by a litany of complaints” from a group of people concerned about the running of the NHS. Whilst Max Keiser argues in his interview with Peter Bach ‘you can’t put a price tag on the NHS’ (see below), you unfortunately can put a price tag on the costs to make this film. If you’d like to support this very important initiative of public interest, please go to this ‘StartJoin’ website for crowdfunding.

If the film set out to achieve a fascinating overview of the issues engulfing the NHS, it certainly did that. The concern, of course, is that this film ends up ‘preaching to the converted’, and it contains still a mystery why the mainstream media seem reluctant to discuss the running of the NHS. Supporters of NHS privatisation have argued that it doesn’t matter who runs the NHS as long as it’s run well and free at the point of use. Supporters of the NHS privatisation therefore tend to argue that the public do not want to have this debate. Conversely, people who support a NHS which is state-run obviously argue, instead, that this debate does matter; and the film indeed posits very good clear arguments why the market does not work in the NHS. The film clearly states that competition doesn’t work effectively for the NHS; measuring all the activity in the NHS itself wastes resources (going up from about 2% of the budget to 30%). The youthful and inspiring Dr Clive Peedell was spitting bullets at the encroachment of the market – and of course is right.

The film flows effortlessly, for example, from an excellent description bogus nature of running the finances of a hospital, compared to a household budget, by Dr Bob Gill to a mention of indexation in the private finance initiative (PFI) by Prof Allyson Pollock. Pollock is clearly somebody who should have been listened to much earlier. At least Pollock is completely vindicated. Whilst politicians of all shades have argued the beneficial effects of PFI, the concerns are brilliantly enuniciated by Pollock. An on-running theme of this film evidently is that it’s not the case that this is a fait accompli of the corporatisation of the NHS, though time is running out now. Something can be done about PFI contracts (and may require attention due to the repercussions of PFI on freedom of information requests concerning safe staffing). It might be late in the day, but it wouldn’t be too late for a candid repentance. Likewise, the public lawyer states correctly the Health and Social Care Act (2012), which led to the £2.4 million ‘reforms’, can be repealed. And it would take one Bill to restore of the duty of the Secretary of State for Health in running the NHS.

Both Dr Jacky Davis and Dr Louise Irvine speak brilliantly in the film on the issues of the ‘democratic deficit’. Given that the mainstream media have continued to ignore the changes in the NHS traditionally, their opinions are clearly a polite (not desperate) plea for members of the general public to become involved. Meanwhile, in the film itself, Dr Lucy Reynolds, who clearly has many interesting insights about cross-jurisdictional aspects of healthcare systems, describes how she left a U.K. where the N.H.S. was respected to one where the N.H.S. was pilloried on a daily basis. I also had a nice chance to chat with Dr Davis and Dr Irvine before the film, and with Dr Jonathon Tomlinson afterwards.

As I left the theatre and the BAFTA building, I caught sight of Lord Owen. On seeing Owen, I was reminded of an interview by the late Tony Benn. Benn’s remarks about how the SDP had been partly launched as a reaction to the inadequacy of Labour still irritate some. In that particular interview these remarks preceded a diatribe also by Benn about how it wasn’t the Left’s fault that Labour had been unelectable. Bach’s film brilliantly doesn’t shovel the blame at the doorstep of any one political party, though clearly no Government (especially this one) comes out of it particularly well.

Many seasoned commentators have learnt that there is a consistent pattern of unsafe practice, where people have not been empowered to speak out safely. I am very glad that Bach’s film approached this intelligently, in a constructive and altogether non-vindictive manner. Peter Brambleby talks with much dignity about how his concerns well known elsewhere fell on deaf ears. Dr Kim Holt also talks about the well known phenomenon of how whistleblowers are first ostracised before being silenced and finally excluded.

The argument that Foundation Trusts, such as Mid Staffs, allegedly made staff cuts endangering patient safety in the rush to meet financial targets to gain Foundation Trust status is elegantly made. Meanwhile, the 6Cs, and indeed lack of minimum staffing, many believe, do not protect against the basic threat of unsafe staffing on the delivery of NHS care.

In a weird way, the film is as iconic as the best of them such as “Breakfast at Tiffany’s”, despite being in a completely different genre. I think it’s inevitable that this film will connect with people in a way which reflects the subject-matter being more significant than the usual party-politics. If the problem was explaining the complex narrative of the failures of NHS policy in a succinct, understandable manner, Bach has just achieved a First with Distinction. It’s a remarkable piece of work, which, whether you are particularly interested in the NHS or not, deserves to be widely seen; and indeed deserves the highest official praise.

Lord Owen's NHS (amended duties and powers) Bill: an eight-clause Bill to restore a comprehensive NHS accountable to parliament

As of early this morning (Tuesday 29 January 2013), the NHA Party and the UK Labour Party seem set to support Lord Owen’s NHS (amended duties and powers) Bill (“the Bill”), as described by Lord Owen himself here, yesterday.

The Health and Social Care Act (2012) ended the Secretary of State’s duty to secure or provide health services throughout the country, a duty that had been in force since 1948. Furthermore, the Act breaks up the universal system that has been effective over sixty years, and provides the NHS trademark for services outsourced to the private sector to maximise the shareholder dividend of those companies.

A major focus of Lord Owen’s Bill is undoubtedly its emphasis, as Lord Owen provides, to “secure a comprehensive, integrated health service”. The Bill in fact contains references to “comprehensive” in clauses 1,5 and 6. The definition of “comprehensive” in the Oxford English Dictionary is indeed a useful starting point, essentially described as “including or dealing with all or nearly all elements or aspects of something“. “Comprehensive” therefore means for most people “all” or “nearly all”, and it’s a matter of interpretation what “nearly” is. This “nearly” aspect has been a slow-burn in policy, for example: “Labour’s national policy forum will debate a draft document on the NHS which contains references to a “largely” comprehensive and “overwhelmingly” free service.”

In March 2011, the NHS published its NHS Constitution, and a leading guiding principle is:

The NHS provides a comprehensive service, available to all irrespective of gender, race, disability, age, sexual orientation, religion or belief

This non-discriminatory aspect of provision of healthcare therefore emphasises equality.

Colin Leys in the Guardian has previously highlighted the effect of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) in deteriorating the comprehensiveness of the service:

Under the bill the range of what is available for free seems certain to contract further. Commissioning groups will have fixed budgets. The for-profit “support organisations” that are being lined up to do most of the commissioning for them will have a strong incentive to limit costs, and therefore the treatments to be paid for. CCGs also look likely to be free to decide that some treatments recommended by hospital specialists are “unreasonably” expensive, and refuse to pay for them, as health maintenance organisations do in the US.

A core of free NHS services will remain, but they will be of declining quality, because for-profit providers will cherry-pick the most profitable services. NHS hospitals will be left with the more costly work, so staffing levels and standards of care will be forced down and waiting times will get longer. To be sure of getting good healthcare people will increasingly take out private insurance, if they can afford it. At first most people will take out the cheaper insurance plans now on offer that cover just what is no longer free from the NHS, but gradually insurance for most forms of care will become normal. The poor will be left with a limited package of free services of lower quality.

What is available on the NHS should be determined nationally, in a transparent and democratic way, not by unelected local bodies. The bill will allow the secretary of state to deny responsibility when good, comprehensive, free care has become a thing of the past.

There are indications that services are being “scaled back”. For example, there have latterly been reports of impact on hearing services, for example:

NHS hearing services are being scaled back in England, an investigation by campaigners suggests.

Data obtained by Action on Hearing Loss from 128 hospitals found more than 40% had seen cuts in the past 18 months.

In particular, the study found evidence of rises in waiting times and reductions in follow-up care.

The report is the latest in a growing number to have suggested front-line care is being rationed as the health service struggles with finances.

The NHS is in the middle of a £20bn five-year savings drive.

The real question is of course how viable is it to have a totally NHS, which is “comprehensive” and “free-at-the-point-of-use”.

Even in the course of yesterday evening, this tweet of mine received 32 retweets, while most of my thread were (quite rightly) pre-occupied about the BBC Panorama documentary on disabled citizens and employment opportunities.

Prof Allyson Pollock and David Price explain the rationale for this urgent Bill as follows (see QMUL press release):

The Abolition of the democratic and legal basis for the NHS in England

The democratic and legal basis for the NHS in England was abolished by the Health and Social Care Act 2012. The impact of this fundamental change is already being felt, ahead of the shift to the new market system in April 2013.

The Act ended the Secretary of State’s duty to secure or provide health services throughout the country, a duty that had been in force since 1948.

A minister may only be held to account legally for services that he or she is responsible for by law. In future, if we can’t get the health care we need, ministers won’t have to worry about being taken to court on this count, and there will be no Primary Care Trust to put pressure on. This means fewer rights for people in England to get the health care we need – at a time of unprecedented cuts and closures.

The Act breaks up the universal system that has served us for over sixty years, and reduces the NHS to a stream of taxpayer funds and a logo for the use of a range of public and corporate providers of services.

A House of Lords’ bill published this week will reinstate the Secretary of State’s legal duty to provide the NHS in England and the right of all of us in England to comprehensive and integrated health care.

By restoring the legal and democratic basis, the new National Health Service (Amended Duties and Powers) Bill will ensure basic questions about citizens’ rights will continue to be determined democratically, as they should be.

This briefing explains what the government is doing and why an urgent bill to reinstate the NHS in England is required.

What does the government’s Act mean for me?

Cutting free NHS services

When the 2012 Act is implemented, the government will no longer be responsible for providing for our health care needs free of charge. The system of health care which has served all people throughout England for over sixty years is being dismantled and broken up. Instead a range of bodies, including for-profit companies, will decide which services will be freely available and who will receive them.

Currently many NHS services are being transferred to local authorities. They can bring in commercial companies to run them and the 2012 Act provides new charging powers. During the passage of the Health and Social Care Bill last year these services included[1]:

- immunization, cancer and cardiovascular screening

- mental health care

- dental public health

- public health

- sexual health services

- management of drug and alcohol addiction

- emergency planning and health protection service

- child health services.

Concerns were repeatedly raised during the passage of the Bill that some services would no longer required by law to be provided free of charge. These services included: [2]

- Services and facilities for pregnant women, women who are breast-feeding

- Services for both younger and older children

- Services for the prevention of illness

- Care of persons suffering from illness and their after-care

- Ambulance services

- Services for people with mental illness

- Dental public health services

- Sexual health services

Putting commercial companies in control

The Act also promotes more marketisation. More and more NHS services are being put out to tender to for-profit companies and taxpayer funds are being given to commercial corporations whilst publicly run health facilities are closed down.

As the 2012 Act is being implemented, corporations will have more say in determining our entitlement to free health services. In future, no single organisation will be responsible in our area for ensuring all our care. And it will no longer be clear who should be held accountable when things go wrong.

Our relationship with our doctor will change when for-profit companies run more services. As a patient we will no longer necessarily come first: how can we feel confident that our doctor is putting us first when he or she is a for-profit company employee?

Privatisation and marketization has increased in advance of the Act.

Some services, including those for the most vulnerable people in society, were last year contracted out to for-profit companies such as Virgin and Serco, which have little or no experience in delivering care. These include services for children with mental health problems and physical disabilities in Devon[3], and community nursing and health visitor services in Surrey[4] and Suffolk[5].

Many NHS hospitals are owned and operated under the expensive private finance initiative, creating serious financial problems for them and putting neighbouring hospitals and services at risk. For-profit companies and investors now control GP practices and other local health services. According to the Financial Times, Virgin already earns around £200 million a year by running more than 100 NHS services nationwide, including GP surgeries.[6] A private company registered in the Virgin Islands now manages the local hospital in Huntingdon, Hinchingbrooke NHS Trust.

The government is manufacturing a financial crisis in the NHS.

It is clear that the government is manufacturing a crisis, reducing the level of services and their quality, and shaking public confidence in the NHS. We are being encouraged to accept the principle that we will in future have to pay privately for services that were once free.

But claims that we can no longer afford the NHS are untrue.

The NHS is not over budget. Last year the NHS budget was underspent and £2 billion was returned to the Treasury.[7] Headline stories about hospital and other health service deficits only mean that resources are unfairly distributed not that the NHS is unaffordable overall.

Government claims that it is protecting the NHS budget are also untrue.

According to the official watchdog, the Statistics Authority: “expenditure on the NHS in real terms was lower in 2011-12 than it was in 2009-10.”[8]

The NHS is being run as if it is in a financial crisis but this crisis is of the government’s making. Current plans for cutting NHS budgets, hospital beds and sacking thousands of vital NHS staff are based on documents drawn up by management consultancy firms including the US company, McKinsey & Co. The policy will lead to closure and hollowing out of public services and the creation of opportunities for an expanded market for private provision and the introduction of user charges.

The policy is fuelling cuts, closures and mergers on a scale that is unparalleled. There is no evidence to support change on this scale nor the unfair distribution of funds[9].

Cuts and closures

- In North West London the government plans to cut 25% of beds, and throughout London at least 7 accident and emergency departments will close[10], with further departments under threat. Up to 5600 jobs in North West London will be lost by 2015[11]. Barnet and Chase Farm Hospitals NHS Trust is cutting 208 posts.[12]

- In Merseyside, 4000 NHS jobs will go by 2014[13]

- In South Yorkshire, Rotherham Hospital is set to lose 750 staff by 2015[14]

- In West Suffolk, Serco is planning to cut 137 Community Healthcare jobs.[15]

- In Devon and Exeter, the Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust plans to cut 1115 full-time equivalent posts between 2011 and 2014.[16]

- In Greater Manchester, there are plans to downgrade Trafford General Hospital’s A&E to urgent care and cuts to intensive care, acute surgery and children’s services. [17] Maternity services have already closed.[18] Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust plans to cut 750 full-time posts by 2013. [19] Bolton NHS trust is making 500 redundancies.[20]

- In Warwickshire, the George Eliot Hospital NHS Trust plans to cut the equivalent of 257 full-time staff between 2010 and 2014.[21]

- In Cornwall, Royal Hospital Truro proposed to cut 400 jobs in 2011.[22]

- In Portsmouth, Queen Alexandra Hospital cut 700 jobs and shut 3 wards in 2011[23].

- Across England, twenty four out of thirty NHS Direct call centres will close[24]

- 6000 nursing posts have been cut since the coalition came to power in 2010.[25]

Mergers

Hospital mergers reduce services and increase waiting times and travel distances.

- Merger with North Tees was followed by closure of A & E in Hartlepool in August 2011[26]

- Merger of South London trust is followed by recommendation of closure of Lewisham hospital A&E. [27]

- Merger of Queen Mary’s Sidcup NHS Trust (QMS), Queen Elizabeth Hospital NHS Trust (QEH) and Bromley Hospitals NHS Trust (BHT) to create a single hospital on several sites in 2009 was followed by closure of Queen Mary’s A&E and labour unit in 2010.[28]

- Merger of Norfolk and Waveney and Suffolk mental health trusts was followed by cuts in beds for acute mental illness and community mental health teams[29]

- Barnet and Chase Farm Hospitals NHS trust currently plans a merger which is likely to result in closure of A&E, maternity and paediatric services [30].

- Merger resulted in closure of Trafford General Maternity Unit in 2010[31] and A&E is threatened.[32]

- Merger with Blackburn Hyndburn and Ribble Valley (BHRV) NHS Trust in 2003 was followed by closure of Burnley A&E in 2008[33] and the paediatric inpatient ward in 2010[34].

- Merger resulted in closure of Rochdale Infirmary, Greater Manchester A&E in 2011[35].

Why a Bill is needed to reverse the worst aspects of the Act?

The Health and Social Care Act 2012 must be changed because it removes the democratic and legal basis of the NHS at a time when services are being cut and reconfigured on an unprecedented scale.

The NHS was created in 1948 by a law requiring the secretary of state to fund and provide all medical, dental and nursing care to the whole population on an equitable basis throughout the country. This duty has been abolished.

The government has no mandate for this Act. We did not vote for the abolition of our NHS. Neither was it a part of the coalition agreement. Unlike England, citizens of Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland will continue to have a NHS.

The purpose and limitations of the urgent Bill

The proposed legislation restores the legal and democratic basis of the NHS and the citizens’ rights ultimately to hold the Secretary of State to account. It will restore the Secretary of State’s duty to provide the NHS in England and gives him or her ministerial powers of direction and planning in order that the duty can be properly discharged.

Specifically, the Bill will:

- reinstate the secretary of state’s duty to provide health services that was formerly contained within sections 1 and 3 of the NHS Act 2006;

- subject all NHS bodies and bodies providing services for the NHS to ministerial direction;

- repeal the duty of autonomy and restore sufficient ministerial control over provision consistent with the secretary of state’s overarching duty to provide health services to the whole of England; and

- give Monitor an objective, so that its purpose is to help deliver the NHS.

The Bill will not require further reorganization when it is passed.

Allyson M Pollock (Professor of Public health research and policy,

David Price (Senior Research Fellow)

Global health, policy and innovation unit

Centre for Primary Care and Public Health

Queen Mary, University of London

58 Turner St, London E1 2AB and R

[1] Pollock AM, Price, DP, Roderick, P. How the Health and Social care Bill2011 would end entitlement to comprehensive health care in England

January 26, 2012 DOI:10.1016/S0140- 6736(12)60119-6

[2] Pollock AM, Price D, Roderick P. Health an social care Bill 2011: a legal basis for charging and providing fewer health services to people in England. BMJ 2012;344:1729- 82

[4] http://www.telegraph.co.uk/health/healthnews/9176733/NHS-patients-to-be-treated-by-Virgin-Care-in-500m-deal.html

[7] Department of Health: Securing the future financial sustainability of the NHS, Sixteenth Report of Session 2012–13, House of Commons, Committee of Public Accounts http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201213/cmselect/cmpubacc/389/389.pdf

[8] Andrew Dilnot, (Chair of the UK Statistics Authority) Letter to Right Hon Jeremy Hunt MP, dated 4th December 2012, http://www.statisticsauthority.gov.uk

[9] ‘Can governments do it better? Merger mania and hospital outcomes in the English NHS’, M Gaynor, M Laudicella and C Propper, CMPO working paper 12/281 http://www.bristol.ac.uk/cmpo/publications/papers/2012/wp281.pdf

[10] http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2200339/NHS-Cuts–Savage-consequences-revealed-pensioner-waits-6-hours-ambulance.html

[11] http://www.healthemergency.org.uk/breakingnews.php Tuesday 23rd October 2012

[12] http://www.enfield-today.co.uk/News.cfm?id=43000&headline=Alarm%20over%20job%20cuts%20at%20hospital

[13] http://www.liverpooldailypost.co.uk/liverpool-news/regional-news/2012/01/19/exclusive-merseyside-nhs-staff-cuts-to-see-4-001-jobs-go-by-2014-99623-30150190

[15] http://www.nursingtimes.net/nursing-practice/clinical-zones/district-and-community-nursing/serco-plans-to-cut-137-community-posts-in-suffolk/5052039.article

[22] http://www.truropeople.co.uk/groups/trurohealth/400-Jobs-Cut-Truro-Royal-Cornwall-Hospital/story-10908019-detail/story.html

[24] http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-2230584/NHS-Direct-close-24-30-centres-claims-union.html

[25] http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/health-news/fears-for-patient-safety-as-60000-nhs-jobs-face-the-axe-8307270.html

[27] http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/health-news/debtridden-nhs-trust-to-be-scrapped-8231436.html

[28] http://www.hsj.co.uk/acute-care/nhs-london-revives-queen-marys-sidcup-closure-plans-amid-patient-safety-concerns/5019638.article

[30] http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/8756245/Government-to-merge-Chase-Farm-Hospital-which-David-Cameron-vowed-to-save.html

[32] http://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/health/trafford-health-trust-to-merge-with-neighbours-866605

[33] http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2207274/A-E-closures-Secret-report-reveals-lives-risk-sweeping-plans-close-25-casualty-units.html

[34]http://www.lancashiretelegraph.co.uk/news/burnley/9016530.Burnley_s_children_ward_to_stay_in_Blackburn/

[35] http://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/local-news/last-chance-to-save-rochdale-infirmary-679318

Lord Owen’s Bill is proposed as below

National Health Service (Amended Duties and Powers) Bill

A

BILL

TO

Re-establish the Secretary of State’s legal duty as to the National Health Service in England, QUANGOS and related bodies.

BE IT ENACTED by the Queen’s most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present

Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:—

1 Secretary of State’s duties to promote and provide a comprehensive and integrated health service

For section 1 of the National Health Service Act 2006 (Secretary of State’s duty to promote comprehensive health service) substitute:

“1 Secretary of State’s duty as to the health service

(1) It shall be the duty of the Secretary of State to promote in England a comprehensive and integrated health service designed to secure improvement –

(a) in the physical and mental health of the people of England, and

(b) in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of illness,

and for that purpose to provide or secure the effective provision of services in accordance with this Act.

(2) The services so provided must be free of charge except in so far as the making and recovery of charges is expressly provided for by or under any enactment, whenever passed.

(3) The services provided pursuant to this Act and to the Health and Social Care Act 2012, howsoever or by whomsoever provided, secured or arranged, shall be deemed to be provided in furtherance of the duty to provide or secure effective provision of services under subsection (1).”

2 Abolition of the duties of autonomy

Section 1D and section 13F of the National Health Service Act 2006 (duties as to promoting autonomy) are repealed.

3 Concurrent duty of and commissioning by the NHS Commissioning Board

(1) Section 1H(2) of the National Health Service Act 2006 is repealed.

(2) In section 1H(3) of that Act, for “For the purpose of discharging that duty,” substitute “For the purpose of furthering the duty of the Secretary of State under section 1(1),”.

4 Secretary of State’s duty as to provision of certain services

(1) Section 3 of the National Health Service Act 2006 is amended as follows.

(2) Before subsection (1) insert—

“(Z1) The Secretary of State must provide or secure the effective provision

throughout England, to such extent as he considers necessary to meet all reasonable requirements, the accommodation, services and facilities set out in subsection (1)(a)-(f).”

(3) In subsection (1), before “A”, insert “For that purpose,”.

5 Power of directions to QUANGOs and other bodies

(1) The Secretary of State may direct any of the bodies mentioned in subsection (2) to exercise any of his functions relating to the health service which are specified in the directions, and may also give directions to any such body about its exercise of any functions or about its provision of services under arrangements referred to in subsection 2(h).

(2) The bodies are—

(a) the National Health Service Commissioning Board

(b) a clinical commissioning group,

(c) a Special Health Authority,

(d) an NHS trust,

(e) an NHS foundation trust,

(f) the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence,

(g) the Health and Social Care Information Centre, and

(h) any other body or person providing services in pursuance of arrangements made—

(i) by the Secretary of State under section 12,

(ii) by the Board or a clinical commissioning group under section 3, 3A, 3B or 4 or Schedule 1,

(iii) by a local authority for the purpose of the exercise of its functions under or by virtue of section 2B or 6C(1) or Schedule 1, or

(iv) by the Board, a clinical commissioning group or a local authority by virtue of section 7A of the National Health Service Act 2006.

(3) In exercising his power under subsection (1), the Secretary of State must have regard to the desirability, so far as consistent with the interests of the health service and relevant to the exercise of the power in all the circumstances—

(a) of protecting and promoting the health of patients and the public;

(b) of any of the bodies mentioned in subsection (2) being free, in exercising its functions or providing services in accordance with its duties and powers, to do so in the manner that it considers best calculated to promote the comprehensive and integrated service referred to in section 1(1) of the National Health Service Act 2006; and

(c) of ensuring cooperation between the bodies mentioned in subsection (2) in the exercise of their functions or provision of services.

(4) If, in having regard to the desirability of the matters referred to in subsection (3) the Secretary of State considers that there is a conflict between those matters and the discharge of his duties under section 1 of the National Health Service Act 2006, he must give priority to the duties under that section.

6 Monitor

(1) The Health and Social Care Act 2012 is amended as follows.

(2) After section 61 insert—

“61A Monitor’s objective

(1) The objective of Monitor is to contribute to the achievement of a comprehensive and integrated health service in England through the exercise of its functions.

(2) In exercising its main duty and other functions Monitor must act in accordance with that objective and in a manner consistent with the performance by the Secretary of State of his duties contained in sections 1 and 3 of the National Health Service Act 2006.”

(3) Section 62(9) is repealed.”

7 Interpretation

Expressions used in this Act which are also used in the National Health Service Act 2006 and in the Health and Social Care Act 2012 shall have the same meanings as the meanings given to those expressions under those Acts.

8 Short title, commencement and extent

(1) This Act may be cited as the National Health Service (Amended Duties and Powers) Act 2013.

(2) This Act shall come into force on the day on which it is passed.

(3) This Act extends to England.