Home » Pharma

The Right needs to make up its mind: is society, or the individual, more important?

Socialism has never been clearer.

We not consider the State to be a ‘swear word’. We are proud of our values of solidarity, social justice, equality, equity, co-operation, reciprocity, and so it goes on.

The Right, meanwhile, needs to make up its mind: is “societal benefit” more important, or the individual?

The rhetoric under Margaret Thatcher and beyond, including Tony Blair, was individual choice and control could ‘empower’ individuals. This was more important than the paternalistic state making decisions on your behalf, and indeed Ed Miliband was keen to read from the same script at the Hugo Young lecture 2014 the other week.

Yet, the phrase “societal good” has been used by an increasingly desperate Right, wishing to justify money making opportunities in caredata, or cost saving measures such as NICE medication approvals or hospital reconfigurations, So where has this individual power gone?

Whilst fiercely disputed now, Thatcher’s idea that ‘there is no such thing as society’ potentially produces a sharp dividing line between the rights of the individual and the value of society.

“There is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women, and there are families. And no government can do anything except through people, and people must look after themselves first. It is our duty to look after ourselves and then to look after our neighbour.

was an individualist in the sense that individuals are ultimately accountable for their actions and must behave like it. But I always refused to accept that there was some kind of conflict between this kind of individualism and social responsibility. I was reinforced in this view by the writings of conservative thinkers in the United States on the growth of an `underclass’ and the development of a dependency culture. If irresponsible behaviour does not involve penalty of some kind, irresponsibility will for a large number of people become the norm. More important still, the attitudes may be passed on to their children, setting them off in the wrong direction.”

(M. Thatcher, Woman’s Own, October 31, 1987)

Whilst the Left has been demonised for promoting a lethargic large State, monolithic and unresponsive, there’s been a growing hostility to large monolithic private sector companies carrying out the State’s functions.

It is alleged that some of these companies are not doing a particularly good job, either.

It has recently been alleged that the French firm, ATOS, judged 158,300 benefit claimants were capable of holding down a job – only for the Department of Work and Pensions to reverse the decision. At the end of last year, private security giants G4S and Serco have been stripped of all responsibilities for electronically tagging criminals in the wake of allegations that the firms overcharged taxpayers

So why should the Right be so keen suddenly on arguments based on ‘societal benefit’?

It possibly is a cultural thing.

The idea that “large is inefficient” was never borne out by the doctrine of ‘economies of scale’, which is used to justify the streamlining of operational processes across jurisdictions for multinational companies.

This was a naked inconsistency with the excitement in corporate circles with “Big Data”, that big is best.

Many medical researchers are rightly excited at the prospect of all this data. Analysis of NHS patient records first revealed the dangers of thalidomide and helped track the impact of the smoking ban. This new era of socialised big NHS data could be very powerful indeed. Whilst there were clearly issues with informed consent at an individual level, the argument for pooling of data for public health reasons were always compelling.

The fact that this Government is simply not trusted when it comes to corporate capture has strongly undermined its case. Also, if the individual must put itself first, why should he allow his data to be given up? Critically, this knowledge doesn’t just have a social good, or multiple individual health ones. It has economic value too.

It might simply be that the Right is keen on this policy through now is precisely because such data will offer significant financial benefits, and that any to wellbeing are simply pleasant side-effects. The concern that this policy is actually about boosting the UK life sciences industry, not patient care. This is science policy – where science lies within the technical jurisdiction of the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills – not just health policy.

Is it not reasonable that an individual should have the right to opt out of having his caredata being absorbed?

“Societal good” has been used by the current Government in a different context too.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) will consult next month on an update to its methodology for assessing drugs. It had been asked by the Department of Health to make judgments on the “wider societal benefit” of medicines before recommending them for NHS use. But a board meeting this week has decided it would be wrong to make an assessment that effectively would put a monetary value on the contribution to society of the people likely to be taking the drugs.

It is thought that any assessment of “wider societal benefit” would inevitably end up taking age into account, say papers from the meeting. “Wider societal benefit” could therefore be simply an excuse for excluding more costly older patients.

NICE’s chief executive, Sir Andrew Dillon, has said it is valid to take into account the benefit to society of a new drug, but great care had to be taken in the way it was done, so that an 85-year-old was not regarded as less important than a 25-year-old. One group of patients should never be compared with another.

But an older individual must put his access to medications first surely?

A legal challenge brought by the local authority and the Save Lewisham hospital campaign showed conclusively that the secretary of state did not have the power to include Lewisham in a solution to the problems of SLHT.

As Caroline Molloy explains:

“The hospital closure clause gives Trust Special Administrators greater powers including the power to make changes in neighbouring trusts without consultation. It was added to the Care Bill just as the government was being defeated by Lewisham Hospital campaigners, in an attempt to ensure that campaigners could not challenge such closure plans in the future. But the new Bill could be applied anywhere in the country.”

Clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), the groups of state representatives making local health plans about resource allocations, will still need to be consulted in this process, and the consultation has been extended to 40 days. However, disagreements between CCGs may now be overruled by NHS England. So, the most important local decision makers may have no say in key reconfigurations of their hospitals and care services.

An individual within a locality must surely have the right to put his own interests regarding social provision first?

I believe that part of the reason the Right has got into so much trouble with caredata, access to drugs and clause 118 is that it appears in fact to ride roughshod over people’s individual rights, and in all three cases is only considering the potential economic benefit to the budget as a whole. They are not interested in the power of the individual at all.

And the most useful explanation now is actually that with such overwhelming corporate capture engulfing all the main political parties, that there’s no such thing as “Left” and “Right” any more. It might have been once our duty to look after ourselves, but it is clear that conflicts have emerged between individual autonomy and the needs of the corporates.

The “Right” is not actually working for the needs of the individual at all, nor of society.

The most parsimonious reason is that the Right is not as such a Right at at all. It, under the subterfuge of being “centre-left” or “centre right”, is simply acting for the needs of the corporates, explaining clearly why so many are disenfranchised from politics. From this level of performance, the Right has not only failed to safeguard the interests of the Society, it has failed to uphold the rights of the individual. This is an utter disgrace, but entirely to be expected if the Government governs on behalf of the few.

Of course we knew that this would happen under the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats, but Labour needs to return to democratic socialism urgently.

Don’t you think it’s very odd a Conservative PM should nationalise something? What is the real issue about patient records?

Even Google gave up on their central database for health information called “Google Health”. Whilst few things are as certain as death and taxes, it is fairly certain that there is big money in big data. Lord Shutt of Greetland, Chair of the Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust Ltd. warned, in a foreword on a recent report on “the database state”, that the problem is huge, and as a society we must face up to formidable challenges. There has always been a tough balance in the law between balancing individual rights of privacy and freedom, with the State’s rights of national policy of health and security, for example. Whatever ideological position the Liberal Democrats eventually settle on, it is striking that a Conservative Prime Minister should actually advocate nationalising something.

It is unsurprising that Big Pharma would have welcomed the move. Andrew Witty, the chief executive of GlaxoSmithKline, stated to the Sunday Telegraph he welcomed the data-sharing initiative: “Any action the government takes to improve the environment in this country for life science across these activities is welcome.” The Autumn Statement (2011) had indeed signposted this. It might seem paradoxical that the Department of Health at this time wishes to embark on an initiative to make the NHS “paperless”, at a time when a reorganisation, estimated at £3bn, is currently underway. Patient data, essential for individual patient security, confidentiality and consent, are “rich pickings” for the private healthcare industry, which have not collectively paid to collect this information nor invest in the IT infrastructure of the NHS, but the ethical concerns are enormous. Personalised medicine, dependent on real-time patient information, is “the next big thing” emergency in the pharmaceutical industry, currently keeping stocks of companies very healthy. However, the professional code for Doctors, from the General Medical Council (“GMC”) is very clear on the regulation of patient confidentiality and privacy: this is contained within “Confidentiality” (2009), and clearly guides doctors on the conflicting balance between confidentiality and disclosure.

There are interesting reasons why the operational roll-out of the National Patient Record failed in 2006-7. It is now reported that all prescriptions, diagnoses, operations and test results will be uploaded on to central computers by the end of next year, and, by 2018, all NHS organisations will be expected to be able to share this information with other hospitals, GPs, ambulances and health trusts. Mr Hunt hopes local councils will sign up to similar systems, along with private care homes. As with the overall direction of travel of the NHS towards an insurance system where private companies pay “a greater part”, this blurring of the need for patient consent has been insidious.

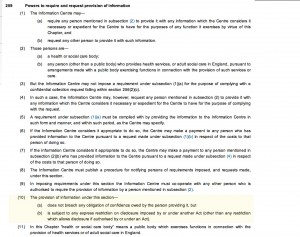

Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006 (originally enacted under Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 2001), allows the common law duty of confidentiality to be set aside in specific circumstances where anonymised information is not sufficient and where patient consent is not practicable. For example a research study may require access to patient identifiable data to allow linkages between different datasets where the cohort is too large for consent. This would require time limited access to identifiable information where gaining consent from a large retrospective cohort would not be feasible and would require more identifiable data than would be necessary for linkage purposes. However, section 10 of the Data Protection Act (1988) currently allows a right for an individual to prevent damage or distress by data processing. This is indeed conveniently “triggered” by section 259(10) of the Health and Social Care Act (2010), i.e. “[the provision] is subject to any express restriction on disclosure imposed by or under another Act (other than any restriction which allows disclosure if authorised by or under an Act”:

The Secondary Uses Service (SUS) Programme supports the NHS and its partners by providing a single source of comprehensive data for planning, commissioning, management, research, audit, public health and “payment-by-results”, a reimbursement mechanism for acute care payments. It is critical to know whether patients their right to opt out of the SUS database. It should not be the case that NHS patients are denied hospital care if they do not agree to my records being sent to SUS. Steve Nowottny in his “Editor’s Blog” for Pulse, a newspaper circulated to GPs, on 8 January 2013 outlined some important very recent developments:

“That year, Pulse ran a ‘Common Sense on IT’ campaign which highlighted a series of concerns over the consent and confidentiality safeguards in the new system.

“GPs wanted patients to have to give explicit rather than merely implied consent before records were created. Plans to use data within the records for research purposes without explicit consent had Catholic and Muslim leaders up in arms, because they feared the research could be purposes contrary to their faiths, such as abortion or stem cell research.

We revealed that celebrities, politicians and other patients whose information is regarded as sensitive would be exempted from the automatic creation of a Summary Care Record, raising questions about the system’s security. And we reported that patients who did not initially choose to opt out of the Summary Care Record would be unable to have their records subsequently deleted.

At the time, it felt as though the stories, while interesting and concerning, were somewhat theoretical. The Summary Care Record’s deployment to date had been patchy and it was far from certain it would continue. In the meantime, fewer than 1% of patients had bothered to opt out. (Now, with nearly 22 million records created and more than 41 million patients contacted, the figure stands at 1.34%).

But the news today that 4,201 patients had Summary Care Records created without them giving even implied consent – and that they will not be able to have them deleted – reignites the whole debate. Suddenly ‘what if’ scenarios have become reality.”

Tim Kelsey is the NCB’s National Director for Patients and Information – his stated aims are to put transparency and public participation at the centre of a transformation of customer service in the NHS. In a recent lecture, he quoted George Soros who said “our social institutions are imperfect, they should be open to improvement [and that] requires transparency and data“. On-line banking and e-ticketing demonstrate the power of open access to personal data in a safe, secure way – for some reason, heath data is deemed more personal that finance and travel arrangements. Data.gov.uk is an example of his vision for the future – the UK has so much medical data, not only about patients but also genomics and other bioinformatics disciplines. The law currently gives the NCB power to mandate more data flows – TK targets April 2014 to get outcomes-based data flows from primary and secondary care – once achieved, next step is to embrace social and specialist care. So, once the data is “freely available”, it can be made available for public participation – he is investing in a course called ‘Code for Health’, a 3 day course to learn how to develop apps. Data is essential from April 2013, there will be push for on-line interaction with GPs, to realise nationally the benefits seen in pilot areas.

So why should commissioners need access to “personal identifiable data”. It is considered that these may be “good reasons”:

- integrated care and monitoring services including outcomes & experience requires linkages across sources

- commissioning the right services for the right people requires the validation that patients belong to CCGs and have received the correct treatments

- aspects of service planning and monitoring on geographic data basis require postcodes for certain type of analysis

- understanding population and monitoring inequalities

- target support for patients and population groups at highest risk requires data from several sources linked together

- specialist commissioning is commissioned outside local areas and can require wider discussions about individual patients and their associated costs

- ensuring appropriate clinical service delivery and process requires access to records

To enable commissioning, ‘personal identifiable data’ including NHS no, DOB, Postcode data needs to flow to “data management integration centres” (“DMICs”). The DMICs need to have similar powers and controls to the Health and Social Care Act information centres to process data In order for processing of PID at DMICs to be undertaken legally, a change in legislation will be required; it is considered that legislative changes can not be achieved by April 2013, and that the new Caldicott is report expected around Jan/Feb 2013. Meanwhile, DMICs need to be operational in April 2013.

David Cameron has stated explicitly his intention for social care to head towards a private insurance system. As stated in the transcript of the interview with Andrew Marr,

“Well the point that was being made earlier on the sofa by Nick Watt, this is a massive problem – that you know more and more people suffering from dementia and other conditions where they go into long-term care and there are catastrophic costs that lead them to have to sell their homes to pay for that care – it’s right to try and put in place a cap which will then open up an enormous insurance market, so people can insure against that sort of catastrophic loss.”

A longrunning conundrum about where there is such intense interest in ‘raising awareness of dementia’. The idea of having GPs and physicians ‘diagnose’ dementia on the basis of a screening test, without it being called ‘screening’ in name, has not been backed up with the appropriate resource allocation for dementia care elsewhere in the system, including adequate training for junior doctors and nurses crucially involved in actual dementia care. Is this and integration of care an entirely virtuous sociological problem? Integration of care at first sight seems to involve primarily avoidance of reduplication of operations, and better ‘coordinated’ care between health and social care and funding. This is not an unworthy ambition at all. It is well known that the endpoint of the Pirie and Butler “Health of Nations” blueprint for NHS privatisation has a greater rôle for the private insurance market as the endpoint, so it makes complete sense to have a fully integrated IT system which private insurers and the Big Pharma can tap into. Lawyers will, of course, be cognisant about the added beauty of integration of clinical and financial information. One of the biggest banes of insurance markets is information asymmetry, making calculation of risk and potential payouts difficult. Insurers will argue that calculation of risk is only possible with precise information, and as I described earlier, clinical commissioning groups are merely “statutory insurance schemes”. It is a long-held belief that private insurers refuse to pay off given the slightest lack of compliance in terms and conditions, but private insurers provide that this mechanism needs to exist to protect them making unnecessary payouts. Failure to disclose medical conditions is an excellent way for private insurers to get out of “paying up”, otherwise known as rescission.

So, given all the above, you can see why the current Government wish to progress with this particular approach to private medical data. The private insurance market and Big Pharma stand to benefit massively, and their lobbying is much more sophisticated than lobbying from GPs, physicians or members of the public. The drive towards all nurses having #ipad3s and all TTOs from Foundation Doctors being sent by broadband to nursing homes may seem utterly virtuous, but there are more significant drivers to this agenda beyond reasonable doubt.