Home » Law (Page 3)

I won my disability living allowance appeal and it surprisingly was an incredibly rewarding experience

This is what you would call perhaps a ‘good news story’ about my disability benefits.

Last Monday, I was invited to Fox Court, Gray’s Inn Road, to go in front of a disability benefits tribunal. I had no idea what to expect. If you ‘Google’ what these tribunals are about, you are likely to draw a blank.

I turned up on time, although I was very nearly late. I think it’s worth treating the tribunal appointment like a job interview. Make sure you turn up with time to spare, so you can compose your thoughts. Where it isn’t like a job interview is that I appeared ‘smart casual’. This is because I have real difficulty in doing buttons and tying shoelaces, and I felt it might be appropriate for the tribunal members to see me how I actually am in my day-to-day life.

Actually, they were very nice to me. I had a panel of three, including a disability expert, and a medical expert. They weren’t overly friendly. There was a huge timer between us, so I know that the entire thing was over in 17 minutes flat.

In the end, it was quite a big deal for me. For me, I had put in an application, and then was not awarded any benefit. I had been on the highest rate of mobility allowance before. I took just in case my old medical notes, but did make it crystal clear to them the date of the reports. They found them useful. I asked for my original submissions to be reviewed, and they made an initial award. I discussed this award with a welfare benefits advisor in a law centre whom I know well. He recommended that it was, in fact, the wrong award, and thought I should appeal. The only voluminous paperwork was the original application form, which you must complete to the best of your ability. The point about the appeal notification is just to let them know you wish to appeal, with a clear reason.

I didn’t have to pay for the appeal. Always tell the truth. Also, only answer the question they ask. Don’t pontificate about anything else. They want to know how far you can walk in metres. They also want to know whether you need help with your living, so think carefully about washing, bathing, shaving, cooking, shopping, getting out of bed, showering, etc. If something doesn’t apply to you, e.g. night-time care, don’t shoehorn possible reasons why it might.

Think about what you’re saying. Make sure that what you’re saying is consistent all the way through. This will be a given if you are telling the truth. But if you say you never go out of the house don’t say you’ve just come back from a hill climbing trek in the Himalayas, etc. This is obviously a ridiculous example, but you know what you mean.

I learnt some basics from the advocacy course in my Legal Practice Course which helped. That is, it really helps if you keep eye contact with the people asking you the questions. I acknowedged that I had a weird squint beforehand, as I have a rare double vision problem. I didn’t use any notes, but I would strongly recommend that you don’t immerse your nose in a bulk of notes. Those notes will only confuse you, and slow you down enormously.

So, anyway it was an entirely constructive experience. Whether or not it is typical, I don’t know. However, I learnt how to trust them. I didn’t take in any tape recorders, as indeed some had advised. I won my appeal. I’m glad I put myself through it, though it can be exasperating and time-consuming as it goes along. As it happens, all the people I spoke to in the Department of Work and Pensions were extremely helpful, but this again could be simply “luck of the draw”. Good luck!

Jeremy Hunt says that 'NHS 111' is now "up-and-running", but that targets should not be gamed

The reality is that the vast majority of hospitals in the NHS are currently failing to see 95% of patients within four hours. Jeremy Hunt was interviewed on the BBC ‘The Andrew Marr Show’ this morning in a wideranging interview which also covered membership of the European Union.

Jeremy Hunt first underplayed the severity of the NHS 111 fiasco, but claimed that things are better now. Of course, one tragedy in care is one too many. The NHS says it has experienced seven “potentially serious” incidents in the first few weeks of its 111 urgent care helpline in England. One case involved a patient in the West Midlands who died unexpectedly and there have been reports of calls going unanswered and poor advice being given. All the cases are being reviewed. Other organisations are also running 111 lines for NHS England and have been warned they must deliver good care or face financial or contract penalties.

In 2010, critics had claimed the change from NHS Direct to NHS 1111 would undermine the quality of the service by reducing the number of qualified nurses answering calls, but chief executive of NHS Direct Nick Chapman said that new helpline would be better and more cost effective. Jeremy Hunt, meanwhile, this morning stated, “There are short-term pressures and long-term pressures. We did have teething problems with NHS 111. It is up-and-running now in 90% of the country. We need to have better alternatives in primary care, a better personal relationship between patients and their GPs”.

“Under the last government, we had a culture of ‘hitting targets at any cost’.” Hunt then went onto blame ‘the target culture’ for bringing about the problems which Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust had faced, leading to two inquiries by Sir Robert Francis QC. Hunt further added that, “I would never blame GPs, because they work extremely hard. I have just been in one.” Of course, nobody seriously would take the blindest bit of difference of Hunt comparing his brief time work experiencing in a GP surgery compared to seven years of basic medical training, including pre-registration training, even prior to specialist GP training.

GPs have experienced a number of contractual changes over time (described here), and latterly it has been mooted that the personal income of GPs, following the latest change, has been steadily eroded as funding levels have been frozen, whilst the running costs of surgeries and staff pay have increased. Hunt provided this morning, “That Contract is one of the contributing causes, because after hours and at weekends the service deteriorates. I don’t want to go back to those days where GPs are personally on call at 2 am.”

Hunt added that, “GPs should have responsibility that people on their list have good service.” It is difficult to see what exactly Hunt means by this, as it is hard to separate out the effect of a medical decision taken out-of-hours compared to a decision compared to during ‘conventional hours’, and one assumes that each Doctor is still responsible for his/her own medical actions to the General Medical Council, wherever he or she provides care.

Hunt then gave a response which managed to combine a welcome for targets in improving care, with direct criticism of those managers clearly gaming the system. Regarding the A&E target, Hunt opined, “It is a very important target, and we have never said we do not have to have good targets. We don’t want people to follow targets at any cost.” However, he then described a series of measures how managers would then ‘game’ the system.

“We had beds which hadn’t been cleaned, ambulances circling hospitals before they entered the front door because they didn’t want the clock the start.”

Outsourcing, NHS, and the “modern anomie”

Jon Cruddas recently gave a progress report on how the evolution of ‘One Nation’ policy was going, In an article by Patrick Wintour published yesterday, Cruddas describes a ‘modern anomie’, a breakdown between an individual and his or her community, and alludes to the challenge of institutions mediating globalisation. Cruddas also describes something which I have heard elsewhere, from Lord Stewart Wood, of a more ‘even’ creation of wealth, whatever this means about the even ‘distribution’ of wealth. One of the lasting legacies of the first global financial crisis is how some people have done extremely well, possibly due to their resilience in economic terms. For example, it has not been unusual for large corporate law firms to maintain a high standard of revenues, while high street law has come close to total implosion in some parts of the country. In a way, this reflects a shift from pooling resources in the State to a neoliberal free market model.

The global financial crash did not see a widespread rejection of capitalism, although the Occupy movement did gather some momentum (especially locally here in St. Paul’s Cathedral). It produced glimpses of nostalgia for ‘the spirit of ’45”, but was used effectively by Conservative and libertarian political proponents are causing greater efficiencies. Indeed, Marks and Spencer laid off employees, in its bid to decrease the decrease in its profits, and this corporate restructuring was not unusual. A conservative and a libertarian have several things in common, the most important is the need for people to take care of themselves for the most part. Libertarians want to abolish as much government as they practically can. It is thought that the majority of libertarians are “minarchists” who favour stripping government of most of its accumulated power to meddle, leaving only the police and courts for law enforcement and a sharply reduced military for national defence. A minority are possibly card-carrying anarchists who believe that “limited government” is a delusion, and the free market can provide better law, order, and security than any goverment monopoly.

Essentially a libertarian would fund public services by privatising them. In this ‘brave new world’, insurance companies could use the free market to spread most of the risks we now “socialise” through government, and make a profit doing so. That of course would be the ideal for many in reducing the spend on the NHS, to produce a rock-bottom service with minimal cost for the masses. And to give them credit, the Health and Social Care Act was the biggest Act of parliament, that nobody voted for, to outsource the operations of the NHS to the private sector, which falls under the rubric of privatisation. Outsourcing is an arrangement in which one company provides services for another company that could also be or usually have been provided in-house. Outsourcing is a trend that is becoming more common in information technology and other industries for services that have usually been regarded as intrinsic to managing a business, or indeed the public sector.

Many expected the election of the present government to herald a more determined approach to outsourcing public services to the private sector. Initially came the idea of the “big society”, with its emphasis on creating and using more social enterprises to deliver public services, but the backers for this new era of venture philanthropism were not particularly forthcoming. The PR of it, through Steve Hilton and colleagues, was disastrous, and even Lord Wei, one of its chief architects, left. No one in the UK likes the idea of domestic jobs moving overseas. But in recent years, the U.K. has accepted the outsourcing of tens of thousands of jobs, and many prominent corporate executives, politicians, and academics have argued that we have no choice, that with globalisation it is critical to tap the lower costs and unique skills of labor abroad to remain competitive. They argue that Government should stay out of the way and let markets determine where companies hire their employees. But is this debate ever held in public? No, there was always a problem with reconciling the need for cuts with an ideological thirst for cutting the State. Unfortunately, cutting the State was cognitively dissonant with cutting the ‘safety net’ of welfare, which is why the rhetoric on scroungers had to be ‘upped’ in recent years by the UK media (please see original source in ‘Left Foot Forward’). And so it came to be, the Compassionate era of Conservatism came to pass.

Here in the UK, in 2010, the government indicated that it wanted to see new entrants into the outsourcing market, and the prime minister visited Bangalore, the heart of India’s IT and outsourcing industry, for high profile meetings with chief executives of companies such as TCS, Infosys, HCL and Wipro. Nobody ever bothers to ask the public what they think about outsourcing, but if Gillian Duffy’s interaction with Gordon Brown is anything to go by, or Nigel Farage’s baptism in the local elections has proved, the public is still resistant to a concept of ‘British jobs for foreign workers’. However, it is still possible that the general public are somewhat indifferent to screw-ups of outsourcing from corporates, in the same way they learn to cope with excessive salaries of CEOs in the FTSE100. The media have trained us to believe that unemployment rights do not matter, and this indeed has been a successful policy pursued by the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. People do not appear to blame the Government for making outsourcing decisions, for example despite the fact that the ATOS delivery of welfare benefits claims processing has been regarded by many as poor, the previous Labour government does not seem to be blamed much for the current fiasco, and the current fiasco has not become a major electoral issue yet.

And the list of screw-ups is substantial. G4S – the firm behind the Olympic security fiasco – has nowbeen selected to support the Police Service of Northern Ireland at the G8 Summit next month. Despite the company’s botched handling of the Olympics Games contract last summer, G4S has been chosen to supply 450 security staff for the event at Lough Erne, County Fermanagh The leaders of the world’s eight wealthiest countries are expected in Fermanagh on June 17 and 18. Meanwhile, medical assessments of benefit applicants at Atos Healthcare were designed to incorrectly assess claimants as being fit for work, according to an allegation of one of the company’s former senior doctors has claimed. Greg Wood, a GP who worked at the company as a senior adviser on mental health issues, said claimants were not assessed in an “even-handed way”, that evidence for claims was never put forward by the company for doctors to use, and that medical staff were told to change reports if they were too favourable to claimants. Elsewhere, Scotland’s hospitals were banned from contracting out cleaning and catering services to private firms as part of a new drive towards cutting the spread of deadly superbugs in the NHS. There were 6,430 cases of C. difficile infections in Scotland in one year recently, of which 597 proved fatal. The problem was highlighted by an outbreak of the infection earlier this year at the Vale of Leven hospital in Dunbartonshire which affected 55 people. The infection was identified as either the cause of, or a contributory factor in, the death of 18 patients.

Whatever our perception of the public perception, the impact on transparency and strong democracy merit consideration. As we outsource any public service, we appear to risk removing it from the checks and balances of good governance that we expect to have in place. Expensive corporate lawyers can easily outmanoeuvre under-resourced government departments, who often appear to be unaware of the consequences, and this of course is the nightmare scenario of the implementation of the section 75 NHS regulations. Even talking domestically, Where contracts privilege commercial sensitivities over public rights, they can be used to exclude the provision of open data or to exempt the outsourcer from freedom of information requests. Talking globally, “competing in the global race” has become the buzzword for allowing UK companies to outsource to countries that do not have laws (or do not enforce laws) for environmental protection, worker safety, and/or child labour. However, all of this is to be expected from a society that we are told wants ‘less for more’, but then again we never have this debate. Are the major political parties afraid to talk to us about outsourcing? Yes, and it could be related to that other ‘elephant in the room’, about whether people would be willing to pay their taxes for a well-run National Health Service, where you would not be worried about your local A&E closing in the name of QUIPP (see this blogpost by Dr Éoin Clarke). Either way, Jon Cruddas is right, I feel; the ‘modern anomie’ is the schism between the individual and the community, and maybe what Margaret Thatcher in fact meant was ‘There is no such thing as community’. If this means that Tony Blair feels that ‘it doesn’t matter who supplies your NHS services’, and we then get invasion of the corporates into the NHS, you can see where thinking like this ultimately ends up.

We've just had a huge debate about the NHS. It's just a pity that it's been the wrong one.

Think of how much time we’ve just all spent, in thinking about the way in which services will be mostly put out for competitive tendering in the National Health Service. One of the first rules in law is that you fight your battles to the hilt, but, at first, you pick the right battles first. This is precisely what Labour appears not to have done. When Harriet Harman recently said on Question Time that the Conservatives are definitely not ‘to be trusted with the NHS’, Harriet curiously did not refer to the battle and war just won by the Conservatives (and Liberal Democrats) over NHS procurement. And yet the public desperately want Labour to stand up for the NHS. One member even suggested that, if Labour gave its unequivocal backing for restoring the NHS, Labour could even find itself with a massive vote winner.

Labour is clearly going through policy strands with a fine tooth comb, looking at, for example, the way in which multinational companies might employ workers at below the national minimum wage; effectively, controlling immigration through a wage policy. It does not appear to have worked out unequivocally whether it would reduce the rate of VAT, meaning possibly that the state borrowing requirement would temporarily increase. But do you see what they all did there? For days, weeks, or even months, we have been subjected to a relentless debate about EU immigration, when most surveys probably place the issue at number ten on the list of voters’ concerns. Unsurprisingly, the economy remains in ‘pole position’, but the ability of Labour to turn the opinion of the public, particularly in the South of England, away from the idea that Labour is ‘fiscally incontinent’ remains unconvincing. Labour is still considered to be the “tax and spend” party, for example, and Miliband appears painfully aware of that. So, when it comes to policy, there seems to be an odd combination of Labour shooting itself in the foot, or completely picking the wrong battles. And then you add in a complete inability to look at elephants in the room. Labour, to state the obvious, has no ability to implement any of its policies, if it is unable to win a General Election, and the confidence of Labour to win an election on its own is reflected accurately in Lord Adonis promoting his book that ‘if he were to form a new Lib-Lab pact, he wouldn’t start from here.‘

The NHS remains pivotal in Labour’s electoral chances, and Labour has been unable to use the resentment over the section 75 NHS regulations to maximise political capital. Why this should have happened in itself is interesting, as Andy Burnham, MP for Leigh, is a more than capable Shadow Secretary of State for Health. One of the issues is an ability to choose the right battle, possibly. Burnham, with some support from the right-wing media and thinktanks, has been banging on about integrated and whole-person care. Whether through conspiracy or cock-up, there will be short-term interest in how integrated care might be delivered. Think about a justification for State spending in the ‘mission impossible’ of implementing a NHS IT system. Why on earth would a right-wing libertarian government promote something which is national? Why on earth should you abort an ethos of ‘bonfire of the QUANGOs’ to introduce the biggest QUANGO in the country, viz NHS England? Whether you’re into conspiracy or cock-up, the integration of financial and medical information (including mental, physical and social care systems) allows for the perfect infrastructure for an insurance-based system. Insurance works on the basis of misrepresentation or non-disclosure to invalidate claims, so ‘big data’ serve a perfect storm for this. It won’t have escaped anybody’s attention that Labour (as indeed the Conservative Party) has been heading towards an insurance-based system for social care, so it does not require a massive ideological leap to think how this could be extended for all care with time. This does not involve any degree of paranoia, please note.

There is overwhelmingly an intellectual depravity in the bereft notion of producing policy through poll results and focus groups. New Labour clearly loved focus groups, with Philip Gould in ‘The Unfinished Revolution’ having devoted much airspace to developing a product in line with customers’ wishes. Of course, the Conservatives have a special affinity for polling organisations themselves, Nadhim Zadawi, in 2000 he co-founded YouGov and on its flotation became its CEO. YouGov is now one of the world leaders in political and business information gathering, polling and analysis. It employs over 400 staff on three continents and is listed on the London Stock Exchange. Again – it begs the question on why should Labour should wish to outdo the Conservatives on its own ability to use polling data? One of the polls which has become a toxic meme is how a high proportion of all voters would not mind who provides the NHS services, as long as it’s free at the point of use. However, this is intrinsically linked to other questions. Would you be prepared more in national insurance if it meant the NHS were able to provide a more comprehensive (universal) service?

It is indeed correct to state that the costs of renationalising the NHS might be overwhelming, although no accurate costings of this have ever been discussed properly. We do know, however, that the current cost of the NHS reorganisation is in the region of £3bn, but estimates of the actual cost inevitably have to be taken with a pinch of salt, as say the cost of Margaret Thatcher’s funeral. But to use this issue as a wish to stop discussion of this area is lazy, as one of the issues, as indeed as with Thatcher’s funeral, is that is this a sensible use of money compared to how it could be used elsewhere (so called “opportunity cost“)? Some people argue that the marketisation of the NHS has failed, in that any money spent on restoring a state-funded NHS would be money well spent. Restoring a state-funded service would get out of the idea of private companies being driven by maximising their profit margin, and not running a ‘more for less’ approach for delivering a service. Cynics might argue that the cost of restoring a state-run service is peanuts compared to waging a war abroad. Many remain unconvinced about the mantra that economic competition drives up quality, when it is the professional standards of healthcare staff, including doctors, nurses and allied health professionals, which appear to be at the heart of quality. The debate we have just had about the mode of procurement in the NHS was not one any of us as such elected; in other words, it has no mandate. If the Conservatives and the right-wing media appear so pre-occupied about having a referendum next parliament on our membership of the EU, many are (rightly) asking why Ed Miliband cannot ask for a mandate to take sensible decisions about the nature of the NHS. It is a given that there will always be a proportion of services which are outsourced to the private sector, but the question should be ‘how much’. Whilst a full-blown privatisation of the NHS has not happened yet, we have not even had a discussion of how much of the NHS should be outsourced.

And anyway Labour has to ask what really concerns all voters? In Mid Staffs and Cumbria, it is reported that there have been concerns about patient safety, and it may be mere coincidence that Labour failed to convince the voters in both places in the local elections over their offerings. However, there is certainly a ‘debate to be had’, about whether “efficiency savings” in the NHS are justified to produce surpluses in the NHS which get ploughed back into the Treasury (and therefore might be used for international overseas aid rather than frontline care.) Labour equally seems unable to look another ‘white elephant’ in the eye. That is of course the concept of a NHS hospital going bust. Should a NHS Trust which is in financial difficulty be simply allowed to go insolvent after a period of administration, or should the State pump money into it to maintain a local service to people in the community? This requires a fundamental reappraisal of how important “solidarity” and “social democracy” are, in fact, to Labour, and whether it wishes to use its extensive brand loyalty to have a mature, if sobering, discussion of the extent to which it wishes to fund a SOCIALIST National Health Service. Whilst in extremis it can be argued that a nostalgic return to ‘The Spirit of ’45” is not attainable, and is the wrong solution for the wrong times, there is a genuine perception that Labour has lost sight of its founding values. And why has this not been addressed in focus groups? It is well known that, in marketing, if you ask the wrong questions, you ubiquitously get the wrong answers.

Labour needs a mandate to confront these issues. And it should not be afraid to look for a resounding mandate, either. Whilst it might stick its fingers in its ears, and claim it’s nothing to do with them (arguing instead for integrated, “whole person” care), unless these ideological issues are confronted, NHS policy will continue to go down a right-wing path. For example, there is not much further to see GP ‘businesses’ being offered by the private sector, and the NHS pays for them; in this model, GP ‘businesses’ could operate under a standard 5-year contract, using NHS branding, under a ‘franchising’ model like Subway. And “The Tony Blair Dictum” is far from resolved, although currently there are issues more worthy of ‘firefighting’ in service delivery, such as the fiasco over ‘1111’. Labour’s problem is that it does not see the NHS as a ‘vote winner’, in the same way it doesn’t see the plight of disabled citizens experiencing difficulty with their benefits or people feeling genuinely threatened by ‘the bedroom tax’ as a top priority. Whilst Labour is unable to prioritise its issues in a way to align its aspirations with the concerns of the general public, there is no way on Earth it can hope to govern a convincing majority. If Labour wishes to learn a really useful trick from marketing, it could no better than to look at the ‘GAP analysis’ – looking at what the current situation is, and what the expectations of people are, and thinking how to get to a position of what people want. If people actually want a socialist universal, comprehensive NHS, paid for not in a private insurance system, Labour can be expected to work hard for a mandate to deliver this. If it doesn’t, that’s another matter, and it can witter on about whole-person care to its heart’s content.

Competitive tendering is no longer the solution; it is very much the problem.

As part of the “Big Society”, medics and lawyers have now been offended over competitive tendering. Competitive tendering is no longer the solution; it is very much the problem.

Yesterday, it was the lawyers’ turn. The Bar Standards Board (“BSB”) yesterday extended (10 May 2013) the first registration deadline for the Quality Assurance Scheme for Advocates in the face of a threatened mass boycott by barristers. The Solicitors Regulation Authority is expected to follow. In a statement yesterday, the BSB said the deadline will be extended from 10 January to 9 March 2014 ‘to ensure the criminal bar will have more time to consider the consequences of government changes to legal aid before registering’. The end of the first registration period will now be after the Ministry of Justice publishes its final response to its consultation on price-competitive tendering. The SRA board is expected to approve a similar extension shortly.

A group of leading academics, including Prof. Richard Moorhead from University College London, indeed wrote yesterday,

“As academics engaged for many years in criminal justice research, we write to express our grave concern about the potentially devastating and irreversible consequences if the government’s plans to cut criminal legal aid and introduce a system of tendering based on price are introduced. Despite the claim by Chris Grayling, the minister of justice, that ‘access to justice should not be determined by your ability to pay’, this is precisely what these planned changes will achieve. This is not about ‘fat cat lawyers’ or the tiny minority of cases that attract very high fees. As we know from the experiences of people like Christopher Jefferies, anyone can find themself arrested for the most serious of crimes. No one is immune from the prospect of arrest and prosecution.”

Previously, it had been the medics’ turn. That did not deter Earl Howe in collaboration with people who clearly did not understand the legislation like Shirley Williams in competition with the medical Royal Colleges, Labour Peers and BMA. The Royal College of Physicians set out their oppositions to competitive tendering articulated their position last month:

Competitive tendering is often considered to promote competition, provide transparency and give all suppliers the opportunity to win business. It may be that price tags are driven down, but most reasonable professionals would actually ask, “At what cost?” Competitive tendering, rather, has a number of well known criticisms.

When making significant purchases, frank and open communication between potential supplier and customer is crucial. Competitive tendering is not conducive to open communication; in fact, it often discourages deep dialogue because in many cases all discussions between a bidder and the purchaser must be made available to all other bidders. Hence, Bidder A may avoid asking certain questions because the questions or answers may help other bidders by revealing Bidder A’s approaches, features, and the like. At the moment, there is a policy drive away from competition towards collaboration, innovation and ‘creating shared value’. Dr. Deming also writing in Out of the Crisis, “There is a bear-trap in the purchase of goods and services on the basis of price tag that people don’t talk about. To run the game of cost plus in industry a supplier offers a bid so low that he is almost sure to get the business. He gets it. The customer discovers that an engineering change is vital. The supplier is extremely obliging, but discovers that this change will double the cost of the items……the vendor comes out ahead.” This is called the cost-plus phenomenon.

Competitive tendering furthermore encourages the use of cheaper resources for delivering products and services. A supplier forced to play the competitive tendering game may come under pressure to keep costs down to ensure he gets a satisfactory profit margin. One way a supplier can lower costs is by using cheaper labour and/or materials. If the cheaper labour and materials are poor quality, the procurer will often end up with inferior, poor quality product or service. However, warranty and other claims may result –raising the price of the true, overall cost. Another area where suppliers may be tempted to lower costs is safety standards. This current administration is particularly keen on outsourcing, and sub-contractors may cut corners and creating safety risks. This is obviously on great concern where patient safety in the NHS has recently been criticised, after the Francis Inquiry over Mid Staffs NHS Foundation Trust. Furthermore, then government agencies, and indeed, private companies use competitive tendering it can take several years to choose a successful bidder, creating a very slow system. The result is the customer can wait incredibly long periods for product or service that may be required quickly. Finally, insufficient profit margin to allow for investment in research and development, new technology or equipment. Already, in the U.S., private “health maintenance organisations” spend as little as possible on national education and training of their workforce.

So the evidence is there. But, as the Queen’s Speech this week demonstrated on minimum alcohol pricing and cigarette packaging, this Government does not believe in evidence-based policy anyway. In the drive for efficiency, with a focus on price and cost in supply chains, the legal and medical professions have had policies imposed on them which totally ignores value. This is not only value in the product, but value in the people making the product. One only needs to refer to the (albeit extreme) example of a worker being retrieved from the rubble of that factory in Bangladesh to realise that working conditions are extremely important. This is all the more hideous since the policies behind the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act (2012) and the Health and Social Care Act (2012) were not in any of the party manifestos (sic) of the U.K. in 2010.

Competitive tendering is no longer the solution; it is very much the problem.

They've run out-of-steam, as outsourcing and making lots of money is not an ideology

A lot of mileage can be made out of the ‘story’ that the Coalition has “run out of steam”, and this week two commentators, Martin Kettle and Allegra Stratton, branded the Queen’s Speech as ‘the beginning of the end’. There is a story that blank cigarette packaging and minimum alcohol pricing policies have disappeared due to corporate lobbying, and one suspects that we will never get to the truth of this. The narrative has moved onto ‘immigration’, where people are again nervous. This taps into an on-running theme of the Conservatives arguing that people are “getting something for nothing”, but the Conservatives are unable to hold a moral prerogative on this whilst multinational companies within the global race are still able to base their operations using a tax efficient (or avoiding) base. Like it or now, the Conservatives have become known for being in the pockets of the Corporates, but not in the same way that the Conservatives still argue that the Unions held ‘the country to ransom’. Except things have moved on. The modern Conservative Party is said to be more corporatilist than Margaret Thatcher had ever wanted it to be, it is alleged, and this feeds in a different problem over the State narrative. The discussion of the State is no longer about having a smaller, more cost-effective State, but a greater concern that ‘we are selling off our best China’ (as indeed the late Earl of Stockton felt about the Thatcherite policy of privatisation while that was still in its infancy). The public do not actually feel that an outsourced state is preferable to a state with shared responsibility, as the public do not feel in control of liabilities, and this is bound to have public trust in privatisation operations (for example, G4s bidding for the probation service, when operationally it underperformed during the Olympics).

It is possibly this notion of the country selling off its assets, and has been doing so under all administrations in the U.K., that is one particular chicken that is yet to come home to roost. For example, the story that the Coalition had wished to push with the pending privatisation of Royal Mail is that this industry, if loss making, would not ‘show up’ on the UK’s balance sheet. There is of course a big problem here: what if Royal Mail could actually be made to run at a profit under the right managers? Labour in its wish to become elected in 1997 lost sight of its fundamental principles. Whether it is a socialist party or not is effectively an issue which seems to be gathering no momentum, but even under the days of Nye Bevan the aspiration of Labour was to become a paper with real social democratic clout. One of the biggest successes was to engulf Britain in a sense of solidarity and shared responsibility, taking the UK away from the privatised fragmented interests of primary care prior to the introduction of the NHS. The criticism of course is that Bevan could not have predicted this ‘infinite demand’ (either in the ageing population or technological advances), but simply outsource the whole lot as has happened in the Conservative-led Health and Social Act (2012) is an expedient short-term measure which strikes at the heart of poverty of aspiration. It is a fallacy that Labour cannot be relevant to the ‘working man’ any more, as the working man now in 2013 as he did in 1946 stands to benefit from a well-run comprehensive National Health Service. Even Cameron, in introducing his great reforms of the public sector in 2010/1 argued that he thought the idea that the public sector was not ‘wealth creating’ was nonsense, which he rapidly, unfortunately forgot, in the great NHS ‘sell off’.

The Conservatives have an ideology, which is perhaps outsourcing or privatisation, but basically it comes down to making money. The fundamental error in the Conservative philosophy, if there is one, is that the sum of individual aspiration is not the same as the value of collective solidarity and sharing of resources. This strikes to the heart of having a NHS where there are winners and losers, for example where the NHS can run a £2.4 bn surplus but there are still A&E departments shutting in major cities. Or why should we tolerate a system of ‘league tables’ of schools which can all too easily become a ‘race to the bottom’? Individual freedom is as relevant to the voter of Labour as it is to the voter of the Conservative Party, but if there is one party that can uphold this it is not the Conservatives or the Liberal Democrats. No-one on the Left can quite ignore why Baroness Williams chose to ignore the medical Royal Colleges, the RCN, the BMA or the legal advice/38 degrees so adamantly, although it does not take Brains of Britain to work out why certain other Peers voted as they did over the section 75 regulations as amended. But the reason that Labour is unable to lead convincingly on these issues, despite rehearsing well-exhausted mantra such as ‘we are the party of the NHS’, is that the general public received a lot of the same medicine from them as they did from the Conservatives or the Liberal Democrats. Elements of the public feel there is not much to go further; the Labour Party will still be the party of the NHS for some (despite having implemented PFI and NHS Foundation Trusts), and the Conservatives will still be party of fiscal responsibility for some (despite having sent the economy into orbit due to incompetent measures culminating in avoidance of a triple-dip).

It doesn’t seem that Labour is particularly up for discussion about much. It gets easily rumbled on what should be straightforward arms of policy. For example, Martha Kearney should have been doing a fairly uncontroversial set-piece interview with Ed Miliband in the local elections, except Miliband came across as a startled, overcaffeinated rabbit in headlights, and refused doggedly to explain why his policy would not involve more borrowing (even when Ed Balls had said clearly it would.) Miliband is chained to his guilty pleasures of being perceived as the figurehead of a ‘tax and spend’ party, which is why you will never hear of him talking for a rise in corporation tax or taxing excessively millionaires (though he does wish to introduce the 50p rate, which Labour had not done for the majority of its actual period in government). It uses terms such as “predistribution” as a figleaf for not doing what many Labour voters would actually like him to do. Labour is going through the motions of receiving feedback on NHS policy, but the actual grassroots experience is that it is actually incredibly difficult for the Labour Party machine even to acknowledge actually well-meant contributions from specialists. The Labour Party, most worryingly, does not seem to understand its real problem for not standing up for the rights of workers. This should be at the heart of ‘collective responsibility’, and a way of making Unions relevant to both the public and private sector. Whilst it continues to ignore the rights of workers, in an employment court of law over unfair dismissal or otherwise, Labour will have no ‘unique selling proposition’ compared to any of the other parties.

Likewise, Labour, like the Liberal Democrats, seems to be utterly disingenious about what it chooses to support. While it seems to oppose Workfare, it seems perfectly happy to vote with the Government for minimal concessions. It opposes the Bedroom Tax, and says it wants to repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2012), but whether it does actually does so is far from certain; for example, Labour did not reverse marketisation in the NHS post-1997, and conversely accelerated it (admittedly not as fast as post-2012). No-one would be surprised if Ed Miliband goes into ‘copycat’ mode over immigration, and ends up supporting a referendum. This could be that Ed Miliband does not care about setting the agenda for what he wants to do, or simply has no control of it through a highly biased media against Labour. Essentially part of the reason that the Conservatives have ‘run out of steam’ is that they’ve run out of sectors of the population to alienate (whether that includes legal aid lawyers or GPs), or run out of things to flog off to the private sector (such as Circle, Serco, or Virgin). All this puts Labour in a highly precarious position of having to decide whether it wishes to stop yet more drifting into the private sector, or having to face an unpalatable truth (perhaps) that it is financially impossible to buy back these industries into the public sector (and to make them operate at a profit). However, the status quo is a mess. The railway industry is a fragmented disaster, with inflated prices, stakeholders managing to cherrypick the products they wish to sell to maximise their profit, with no underlying national direction. That is exactly the same mess as we have for privatised electricity, or privatised telecoms. That is exactly same mess as we will have for Royal Mail and the NHS. The whole thing is a catastrophic fiasco, and no mainstream party has the bottle to say so. The Liberal Democrats were the future once, with Nick Clegg promising to undo the culture of ‘broken promises’ before he reneged on his tuition fees pledge. UKIP are the future now, as they wish to get enough votes to have a say; despite the fact they currently do not have any MPs, if they continue to get substantial airtime from all media outlets (in a way that the NHS Action Party can only dream of), the public in their wisdom might force the Conservatives or Labour to go into coalition with UKIP.

There is clearly much more to politics than our membership of Europe, and, while the media fails to cover adequately the destruction of legal aid or the privatisation of the NHS, the quality of our debate about national issues will continue to be poor. Ed Miliband must now focus all of his resources into producing a sustainable plan to govern for a decade, the beginning of which will involve an element of ‘crisis management‘ for a stagnant economy at the beginning. The general public have incredibly short memories, and, although it has become very un-politically correct to say so, their short-termism and thirst for quick remedies has led to this mess. Ed Miliband seems to be capable of jumping onto bandwagons, such as over press regulation, but he needs to be cautious about the intricacies of policy, some of which does not require on a precise analysis of the nation’s finances at the time of 7th May 2015. With no end as yet in sight for Jon Cruddas’ in-depth policy review, and for nothing as yet effectively Labour to campaign on solidly, there is no danger of that.

Is the pilot always to blame if things go wrong in a safety-compliant plane in the NHS?

The “purpose” of an air plane crash investigation is apparently as set out in the tweet below:

It seems appropriate to extend the “lessons from the aviation industry” in approaching the issue of how to approach blame and patient safety in the NHS. Dr Kevin Fong, NHS consultant at UCHL NHS Foundation Trust in anaesthetics amongst many other specialties, highlighted this week in his excellent BBC Horizon programme how an abnormal cognitive reaction to failure can often make management of patient safety issues in real time more difficult. Approaches to management in the real world have long made the distinction between “managers” and “leaders” and it is useful to consider what the rôle of both types of NHS employees might be, particularly given the political drive for ‘better leadership’ in the NHS.

In corporates, reasons for ‘denial about failure’ are well established (e.g. Richard Farson and Ralph Keyes writing in the Harvard Business Review, August 2002):

“While companies are beginning to accept the value of failure in the abstract-at the level of corporate policies, processes, and practices-it’s an entirely different matter at the personal level. Everyone hates to fail. We assume, rationally or not, that we’ll suffer embarrassment and a loss of esteem and stature. And nowhere is the fear of failure more intense and debilitating than in the competitive world of business, where a mistake can mean losing a bonus, a promotion, or even a job.”

Farson and Keyes (2011) identify early-on for potential benefits of “failure-tolerant leaders”:

“Of course, there are failures and there are failures. Some mistakes are lethal-producing and marketing a dysfunctional car tire, for example. At no time can management be casual about issues of health and safety. But encouraging failure doesn’t mean abandoning supervision, quality control, or respect for sound practices, just the opposite. Managing for failure requires executives to be more engaged, not less. Although mistakes are inevitable when launching innovation initiatives, management cannot abdicate its responsibility to assess the nature of the failures. Some are excusable errors; others are simply the result of sloppiness. Those willing to take a close look at what happened and why can usually tell the difference. Failure-tolerant leaders identify excusable mistakes and approach them as outcomes to be examined, understood, and built upon. They often ask simple but illuminating questions when a project falls short of its goals:

- Was the project designed conscientiously, or was it carelessly organized?

- Could the failure have been prevented with more thorough research or consultation?

- Was the project a collaborative process, or did those involved resist useful input from colleagues or fail to inform interested parties of their progress?

- Did the project remain true to its goals, or did it appear to be driven solely by personal interests?

- Were projections of risks, costs, and timing honest or deceptive?

- Were the same mistakes made repeatedly?”

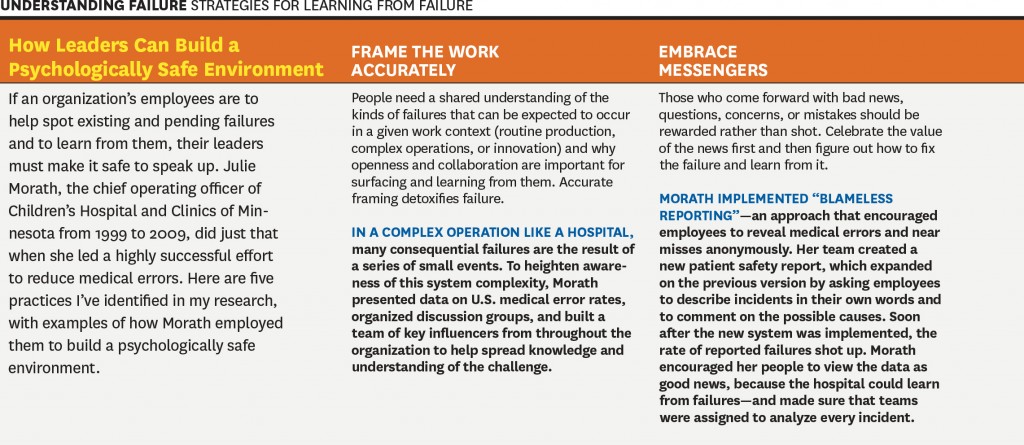

It is incredibly difficult to identify who is ‘accountable’ or ‘responsible’ for potential failures in patient safety in the NHS: is it David Nicholson, as widely discussed, or any of the Secretaries of States for health? There is a mentality in the popular media to try to find someone who is responsible for this policy, and potentially the need to attach blame can be a barrier to learning from failure. For example, Amy C Edmondson also in the Harvard Business Review writes:

“The wisdom of learning from failure is incontrovertible. Yet organizations that do it well are extraordinarily rare. This gap is not due to a lack of commitment to learning. Managers in the vast majority of enterprises that I have studied over the past 20 years—pharmaceutical, financial services, product design, telecommunications, and construction companies, hospitals, and NASA’s space shuttle program, among others—genuinely wanted to help their organizations learn from failures to improve future performance. In some cases they and their teams had devoted many hours to after-action reviews, post mortems, and the like. But time after time I saw that these painstaking efforts led to no real change. The reason: Those managers were thinking about failure the wrong way.”

Learning from failure is of course extremely important in the corporate sectors, and some of the lessons might be productively transposed to the NHS too. This is from the same article:

However, is this is a cultural issue or a leadership issue? Michael Leonard and Allan Frankel in an excellent “thought paper” from the Health Foundation begin to address this issue:

“A robust safety culture is the combination of attitudes and behaviours that best manages the inevitable dangers created when humans, who are inherently fallible, work in extraordinarily complex environments. The combination, epitomised by healthcare, is a lethal brew.

Great leaders know how to wield attitudinal and behavioural norms to best protect against these risks. These include: 1) psychological safety that ensures speaking up is not associated with being perceived as ignorant, incompetent, critical or disruptive (leaders must create an environment where no one is hesitant to voice a concern and caregivers know that they will be treated with respect when they do); 2) organisational fairness, where caregivers know that they are accountable for being capable, conscientious and not engaging in unsafe behaviour, but are not held accountable for system failures; and 3) a learning system where engaged leaders hear patients and front-line caregivers’ concerns regarding defects that interfere with the delivery of safe care, and promote improvement to increase safety and reduce waste. Leaders are the keepers and guardians of these attitudinal norms and the learning system.”

Whatever the debate about which measure accurately describes mortality in the NHS, it is clear that there is potentially an issue in some NHS trusts on a case-by-case issue (see for example this transcript of “File on 4″‘s “Dangerous hospitals”), prompting further investigation through Sir Bruce Keogh’s “hit list“) Whilst headlines stating dramatic statistics are definitely unhelpful, such as “Another nine hospital trusts with suspiciously high death rates are to be investigated, it was revealed today”, there is definitely something to investigate here.

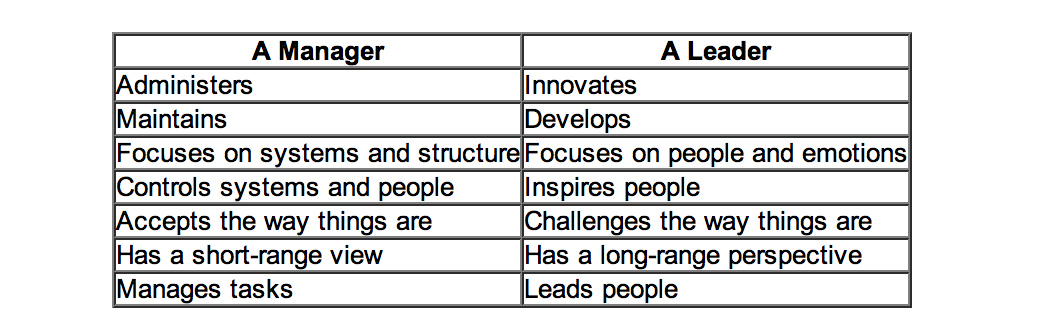

Is this even a leadership or management thing? One of the most famous distinctions between managers and leaders was made by Warren Bennis, a professor at the University of Southern California. Bennis famously believes that, “Managers do things right but leaders do the right things”. It is argued that doing the right thing, however, is a much more philosophical concept and makes us think about the future, about vision and dreams: this is a trait of a leader. Bennis goes on to compare these thoughts in more detail, the table below is based on his work:

Differences between managers and leaders

Indeed, people are currently scrabbling around now for “A new style of leadership for the NHS” as described in this Guardian article here.

Is patient safety predominantly a question of “teamwork”?

Amalberti and colleagues (Amalberti et al., 2005) make some interesting observations about teamwork and professionalism:

“A growing movement toward educating health care professionals in teamwork and strict regulations have reduced the autonomy of health care professionals and thereby improved safety in health care. But the barrier of too much autonomy cannot be overcome completely when teamwork must extend across departments or geographic areas, such as among hospital wards or departments. For example, unforeseen personal or technical circumstances sometimes cause a surgery to start and end well beyond schedule. The operating room may be organized in teams to face such a change in plan, but the ward awaiting the patient’s return is not part of the team and may be unprepared. The surgeon and the anesthesiologist must adopt a much broader representation of the system that includes anticipation of problems for others and moderation of goals, among other factors. Systemic thinking and anticipation of the consequences of processes across depart- ments remain a major challenge.”

Weisner and colleagues (Weisner et al., 2010) have indeed observed that:

“Medical teams are generally autocratic, with even more extreme authority gradient in some developing countries, so there is little opportunity for error catching due to cross-check. A checklist is ‘a formal list used to identify, schedule, compare or verify a group of elements or… used as a visual or oral aid that enables the user to overcome the limitations of short-term human memory’. The use of checklists in health care is increasingly common. One of the first widely publicized checklists was for the insertion of central venous catheters. This checklist, in addition to other team-building exercises, helped significantly decrease the central line infection rate per 1000 catheter days from 2.7 at baseline to zero.”

M. van Beuzekom and colleagues (van Beuzekom et al., 2013) and colleagues, additionally, describe an interesting example from the Netherlands. Teams in healthcare are co-incidentally formed, similar to airline crews. The teams consist of members of several different disciplines that work together for that particular operation or the whole operating day. This task-oriented team model with high levels of specialization has historically focused on technical expertise and performance of members with little emphasis on interpersonal behaviour and teamwork. In this model, communication is informally learned and developed with experience. This places a substantial demand on the non-clinical skills of the team members, especially in high-demand situations like crises.

Bleetman and colleagues (Bleetman et al., 2011) mention that, “whenever aviation is cited as an example of effective team management to the healthcare audience, there is an almost audible sigh.” Debriefing is the final teamwork behaviour that closes the loop and facilitates both teamwork and learning. Sustaining these team behaviours depends on the ability to capture information from front-line caregivers and take action. In aviation, briefings are a ‘must-do’ are not an optional extra. They are performed before every take-off and every landing. They serve to share the plan for what should happen, what could happen, to distribute the workload efficiently and to prevent and manage unexpected problems. So how could we fit briefings into emergency medicine? Even though staff may be reluctant to leave the computer screen in a busy department, it is likely to be worth assembling the team for a few minutes to provide some order and structure to a busy department and plan the shift.

Briefing points apparently could cover:

- The current situation

- Who is present on the team and their experience level

- Who is best suited to which patients and crises so that the most effective deployment of team members occurs rathe than a haphazard arrangement

- The identification of possible traps and hazards such as staff shortages ahead of time

- Shared opinions and concerns.

The authors describe that, “at the end of the shift a short debriefing is useful to thank staff and identify what went well and what did not. Positive outcomes and initiatives can be agreed.”

Is patient safety predominantly a question of “leadership”?

The literature identifies that overall team members are important who have a good sense of “situational awareness” about the patient safety issue evolving around them. However, it is being increasingly recognised that to provide effective clinical leadership in such situations, the “team leader” needs to develop a certain set of non-clinical skills. This situation demands more than currency in advance paediatric life support or advanced trauma life support; it requires the confidence (underpinned by clinical knowledge) to guide, lead and assimilate information from multiple sources to make quick and sound decisions. The team leader is bound to encounter different personalities, seniority, expectations and behaviours from members of the team, each of whom will have their own insecurities, personality, anxieties and ego.

Amalberti and colleagues (Amalberti et al., 2005) begin to develop a complex narrative on the relationship between leadership and management (and the patients whom “they serve”):

“Systems have a definite tendency toward constraint. For example, civil aviation restricts pilots in terms of the type of plane they may fly, limits operations on the basis of traffic and weather conditions, and maintains a list of the minimum equipment required before an aircraft can fly. Line pilots are not allowed to exceed these limits even when they are trained and competent. Hence, the flight (product) offered to the client is safe, but it is also often delayed, rerouted, or cancelled. Would health care and patients be willing to follow this trend and reject a surgical procedure under circumstances in which the risks are outside the boundaries of safety? Physicians already accept individual limits on the scope of their maximum performance in the privileging process; societal demand, workforce strategies, and competing demands on leadership will undermine this goal. A hard-line policy may conflict with ethical guidelines that recommend trying all possible measures to save individual patients.”

Conclusion

Even if one decides to blame the pilot of the plane, one has to wonder the extent to which the CEO of the entire airplane organisation might to be blame. The question for the NHS has become: who exactly is the pilot of plane? Is it the CEO of the NHS Foundation Trust, the CEO of NHS England, or even someone else? And rumbling on in this debate is whether the plane has definitely crashed: some relatives of passengers are overall in absolutely no doubt that the plane has crashed, and they indeed have to live with the wreckage daily. Politicians have then to decide whether the pilot ought to resign (has he done something fundamentally wrong?) or has there been something fundamentally much more distal which has gone wrong with his cockpit crew for example? And, whichever figurehead is identified if at all for any problems in this particular flights, should the figurehead be encouraged to work in a culture where problems in flying his plane have been identified and corrected safely? And finally is this is a lone airplane which has crashed (or not crashed), and are there other reports of plane crashes or near-misses to come?

References

Learning from failure

Farson, R. and Keyes, R. (2002) The Failure Tolerant Leader, Harvard Bus Rev, 80(8):64-71, 148.

Edmondson, A. Strategies for learning from failure, Harvard Bus Rev, ;89(4):48-55, 137.

Patient safety

Amalbert, R., Auroy, Y., Berwick, D., and Barach, P. (2005) Five System Barriers to Achieving Ultrasafe Health Care, Ann Intern Med, 142, pp. 756-764.

Bleetman, A., Sanusi, S., Dale, T., and Brace, S.(2012) Human factors and error prevention in emergency medicine, Emerg Med J, 29, pp. 389e393. d

Federal Aviation Administration, Section 12: Aircraft Checklists for 14 CFR Parts 121/135 iFOFSIMSF.

Pronovost, P., Needham, D., Berenholtz, S., Sinopoli, D., Chu, H., Cosgrove, S., Sexton, B., Hyzy, R., Welsh, R., Roth, G., Bander, J., Kepros, J., and Goeschel, C. (2006) An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU, N Engl J Med, 355, pp. 2725–32.

van Beuzekom, M., Boer, F., Akerboom, S., and Dahan, A. (2013) Perception of patient safety differs by clinical area and discipline, British Journal of Anaesthesia, 110 (1), pp. 107–14.

Weisner, T.G., Haynes, A.B., Lashoher, A., Dziekman, G., Moorman, D.J., Berry, W.R., and Gawande, A.A. (2010) Perspectives in quality: designing the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 22(5), pp. 365–370.

A response to Tony Blair's "advice" this morning

This is a response to “Labour must search for answers and not merely aspire to be a repository for people’s anger”, by Tony Blair, published in the New Statesman on 11 April 2013.

Fundamentally, Blair is right in that Labour cannot merely be a conduit for ‘the protest vote’, but the issues raised by heir to Thatcher are much more than that to me. Blair argues that, “the paradox of the financial crisis is that, despite being widely held to have been caused by under-regulated markets, it has not brought a decisive shift to the left.” I am not so sure about that. Whilst I have always felt the taxonomy of ‘left’ versus ‘right’ largely unhelpful in British politics, I think most people in the country today share views about bankers and the financial services ‘holding the country to ransom’ (like the Union Barons used to be accused of), the failures of privatisation, the failures in financial regulation (PPIs), for example, which might have been seen as ‘on the left’. Tony Blair had a good chance of coming to power in 1997, and ‘the pig with a Labour rosette might have won at the 1997 General Election’ is not an insubstantial one. To ignore that there has been no shift in public opinion is to deny that the political and social landscape has changed to some degree. Whilst ‘South Shields man’ is still living with the remants of the ‘socially divisive’ Thatcherite government, what Michael Meacher MP politely called yesterday “a scorched earth approach”, voters are indeed challenging flagship Thatcherite policies even now.

Some Labour councillors and MPs did indeed embrace the ‘right to buy’ policy, but likewise many MPs of diverse political aetiology warn about the currentcrisis in social housing. Blair is right to argue, “But what might happen is that the left believes such a shift has occurred and behaves accordingly”, in the sense that Ed Miliband does not wish to disenfranchise those voters who did happen to embrace New Labour pursuant to a long stretch of the Conservative sentence, but we have a very strong danger now of disenfranchise the core voters of Labour. They are rightly concerned about workers’ and employees’ rights, a minimum wage (a Blair achievement), and a living wage (possibly a 2015 manifesto pledge by Ed Miliband.) Nobody wants to re-fight the battle of ‘left’ and ‘right’ of those terms, but merely ‘building on’ the purported achievements of Margaret Thatcher has to be handled with care.

Blair further remarks: “The Conservative Party is back clothing itself in the mantle of fiscal responsibility, buttressed by moves against “benefit scroungers”, immigrants squeezing out British workers and – of course – Labour profligacy.” Of course, Blair does not address the growth of the welfare dependency culture under Margaret Thatcher, but this is essential. Blair has also airbrushed the core of the actual welfare debate, about ensuring that disabled citizens have a ‘fair deal’ about their benefits, but to his credit addresses the issue of pensions in his fourth question. However, Blair falls into the trap also of not joining up thinking in various arms of policy, in other words how immigrants have in fact contributed to the economy of the UK, or contributed essential skills to public services such as the National Health Service. This is indeed a disproportionate approach to immigration that was permeating through the language of Labour ministers in immigration towards the end of their period of government. Blair fundamentally wishes to fight this war – indeed battle – on his terms and Thatcher’s terms. This is not on – this debate is fundamentally about the divisive and destructive nature of policy, of pitting the unemployed against the employed, the disabled against the non-disabled, the immigrant versus the non-immigrant, and so on. Part of the reason that Thatcher’s entire hagiography cannot be a bed of roses is that there exists physical evidence today of this ‘divide-and-rule’ approach to leadership.

Blair, rather provocatively at this stage, refers to the ‘getting the house in order’, which is accepting the highly toxic meme of ‘A Conservative government always has to come in to repair the mess of a Labour government spending public money it doesn’t have.’ However, the economy is in a worse state than bequeathed by Labour in 2010, and therein lies the problem that the house that the Tories ‘is getting in order’ is in fact getting worse. Acknowledgement of this simple economic fact by Blair at this juncture would be helpful. Blair’s most potent comment in the whole passage is: “The ease with which it can settle back into its old territory of defending the status quo, allying itself, even anchoring itself, to the interests that will passionately and often justly oppose what the government is doing, is so apparently rewarding, that the exercise of political will lies not in going there, but in resisting the temptation to go there.” Like all good undergraduates, even at Oxford, this depends on what exactly Blair means by the “status quo” – the “status quo” is in Thatcherism, and the “greatest achievement” of Conservatism, “New Labour”, so a return to listening to the views of Union members, ahead of say the handful of wealth creators in the City, is in fact a radical shift back to where we were. In other words, a U-turn after a U-turn gets you back to the same spot.

Blair then has a rather sudden, but important, shift in gear. He writes, “The guiding principle should be that we are the seekers after answers, not the repository for people’s anger.” This is to some extent true from the law, as we know from the views from LJ Laws who has described the challenges of making dispassionate legal decisions even if the issues are of enormous significance in social justice. Blair, consistent with an approach from a senior lawyer remarks, “In the first case, we have to be dispassionate even when the issues arouse great passion.” But then he follows, “In the second case, we are simple fellow-travellers in sympathy; we are not leaders. And in these times, above all, people want leadership.” Bingo. This is what. Whatever Ed Miliband’s ultimate ideology, which appears to be an inclusive form of social democracy encouraging corporate as well as personal citizenship, people ultimately want a very clear roadmap of where he is heading. The infamous articulation of policy under Cruddas will help here, but, as Ed Miliband finds his feet, Miliband will be judged on how he responds to challenges, like Thatcher had to respond to the Falklands’ dispute or the Miners’ Strike.

Blair fundamentally is right to set out the challenges. In as much as the financial crisis has not created the need for change per se, to say that it has not created a need for a financial response is ludicrous. The ultimate failure in Keynesian policy from Blair and Brown is that the UK did not invest adequately in a period of growth, put tritely by the Conservatives as “not mending the roof while the sun was shining”. Mending the roof, to accept this awful image, is best done when the sun is shining. Therefore, Labour producing a policy now is to some extent not the best time to do it. Blair had a great opportunity to formulate a culture in the UK which reflected Labour’s roots in protecting the rights and welfare of workers, but it decided not to do so. Tarred with the ‘unions holding the country to ransom’ tag, it decided to Brown-nose the City quite literally, leading to an exacerbation of the inequality commenced under Thatcher. Blair skirts round the issue of globalisation and technology in a rather trite manner, one assumes for brevity, but the wider debate necessarily includes the effects of globalisation and technology on actual communities in the UK, and the effect of multi-national corporates on life in the UK. Even Thatcher might have balked at the power of the corporates in 2013 in the same way she was critical of the power of the Unions throughout all of her time in government.

Whilst “Labour should be very robust in knocking down the notion that it “created” the crisis”, there is no doubt that Labour has a ‘debate to be had’ about how the Conservatives did not oppose the legislation of the City at the time by New Labour (and even advanced further under-regulation), why George Osborne wished to meet the comprehensive spending review demands of the last Labour government, and how the Conservatives would not have reacted any differently in injecting £1 TN into bank recapitalisation at the time of the crisis. The idea of spending money at the time of a recession has been compared to supporters of FA Hayek as ‘hair of the dog after a big binge’, but unfortunately is directly relevant to Blair’s first question: “What is driving the rise in housing benefit spending, and if it is the absence of housing, how do we build more?” Kickstarting the economy and solving the housing crisis would indeed be a populist measure, but the arguments against such a policy remain thoroughly unconvincing. The second question, “How do we improve the skillset of those who are unemployed when the shortage of skills is the clearest barrier to employment?”, is helpful to some extent, but Blair again shows that he is stuck in a mysterious time-warp; two of the biggest challenges in employment, aside from the onslaught in unfair dismissal, are the excessive salaries of CEOs (necessitating a debate about redistribution, given Labour’s phobia of the ‘tax and spend’ criticism), and how to help the underemployed. The third question is, course, hugely potent: “How do we take the health and education reforms of the last Labour government to a new level, given the huge improvement in results they brought about?” Fair enough, but the immediate problem now is how to slow down this latest advance in the privatisation of the NHS through the Health and Social Care Act (2012), and for Labour to tackle real issues about whether it really wishes to pit hospital versus hospital, school versus school, CCG against CCG, etc. (and to allow certain entities, such as NHS Foundation Trusts, “fail” in what is supposed to be a “comprehensive service”). The other questions which Blair raises are excellent, and indeed I am extremely happy to see that Blair calls for a prioritisation of certain planks of policy, such as how to produce an industrial strategy or a ‘strategy for growth’, and how to deal with a crisis in social justice? There is no doubt that the funding of access-to-justice on the high street, for example in immigration, housing or welfare benefits, has hit a crisis, but Blair is right if he is arguing that operational tactics are not good enough. Sadiq Khan obviously cannot ‘underachieve and overpromise’ about reversing legal aid cuts, but Labour in due course will have to set out an architecture of what it wishes to do about this issue.

Ed Miliband knows that this is a marathon, not a sprint. He has the problem of shooting at a goal, which some days looks like an open goal, other days where the size of the goal appears to have changed, and, on other days, where he looks as if he runs a real risk of scoring an ‘own goal’. It is of course very good to have advice from somebody so senior as Tony Blair, who will be a Lord in the upper chamber in due course, and Miliband does not know yet if he will ‘squeak through’ in the hung parliament, win with a massive landslide, or lose. Labour will clearly not wish to say anything dangerous at the risk of losing, through perhaps offending Basildon Man, and, whilst it is very likely that South Shields Man will remain loyal, nothing can be taken for granted for Ed Miliband unfortunately. Like Baroness Thatcher’s death, Tony Blair’s advice at this stage was likely to rouse huge emotions, and, whilst the dangers of ignoring the advice might not be as costly as Thatcher’s funeral, it would be unwise to ignore his views which, many will argue, has some support within Labour. However, it is clearly the case that some of the faultlines in the Thatcher society and economy have not been healed by the New Labour approach, and Ed Miliband, many hope, will ultimately forge his own successful destiny.

What will a Miliband-Thatcher brand achieve?

Characterising the leadership of Margaret Thatcher is difficult. The problem is that, despite the perceived ‘successes’ of her tenure of government, her administration is generally accepted to have been very socially divisive. For many, she is the complete opposite of ‘inspirational’, and yet listening to current Conservative MPs talk there is a genuine nostalgia and affection for her period of government.

What can Ed Miliband possibly hope to emulate from the leadership style of Margaret Thatcher? Thatcher’s early leadership can definitely be characterised as a ‘crisis’ one, in that full bin liners were not being collected from the streets, there were power blackouts, Britain was going to the IMF to seek a loan, for example. However, the crisis now is one which does not have such visible effects. Miliband can hope to point to falling living standards, or increasing prices due to privatised industries making a profit through collusive pricing, but this is an altogether more subtle argument. A key difference is that people can only blame the business models of the privatised industries, not government directly. Whether this will also be the case as an increasing proportion of NHS gets done by private providers is yet to be seen.

It is perhaps more likely that Thatcher’s leadership, in the early stages at least, migth be described as “charismatic”, involving both charisma and vision. Conger and Karungo famously described five behavioural attributes of charismatic leadership. They are: vision and articulation, sensitivity to the environment, sensitivity to member needs, personal risk taking, and performing unconventional behaviour. In a weird way, Thatcher in her period of government can claim to have provided examples of many of these, but it is the period of social destruction at the time of closure of coal mines which will cause doubt on sensitivity to the environment. While ‘Basildon man’ and ‘Ford mondeo’ man might have been looked after, apparently, ‘Easington man’ was clearly not. A ‘One Nation’ philosophy promoting one economy and one society might not be a trite construct for this, after all. The problem is that ‘Basildon man’ has himself moved on; the ‘right to buy’ is the flagship Tory policy epitomising independence, aspiration and choice for the modern Tory, as resumed by Robert Halfon, but there is ultimately a problem if Basildon man is not able to maintain mortgage payments, or there is a general dearth of social housing.

In a way, looking at the failures of Thatcher’s leadership style is a bit academic now, but still highly relevant in reminding Miliband that his ‘political class’ cannot be aloof from the voters. It is a testament to the huge ‘brand loyalty’ of the Thatcher brand that there are so many eulogies, and one enduring hagimony from the BBC, to Thatcher. Jay Conger provides a way of understanding how charismatic leadership is to be maintained, and the “Poll Tax” is symptomatic of Thatcher’s failure of these aspects. Conger identifies continual assessment of the environment, and an ability to build trust and commitment not through coercion. Miliband likewise needs to be mindful of his immediate environment too: his stance on Workfare disappointed many members of Labour, causing even 41 of his own MPs to rebel against the recent vote, and upset many disabled citizens who are members of Labour. What happens when charismatic leadership goes wrong can be identified clearly in the latter years of the Thatcher administration. These include relatively unchallenged leadership, a tendency to gather “yes men”, and a tendency to narcissism and losing touch with reality. I still remember now (and I am nearly 39), the classic, “We have become a grandmother” and that awful Mansion House spectacle when Mrs Thatcher proclaimed that ‘the batting had been tough of late’ whilst maintaining a quasi-regal ambience.