Home » Dementia (Page 5)

You need risk to live well with dementia

“Risk” is one of those entities which bridges the financial world with law and regulation, psychology or neuroscience. The simplicity of the definition of it in the Oxford English Dictionary rather belies its complexity?

It was a pivotal part of my own Ph.D. in the early diagnosis of the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia, awarded by the University of Cambridge in 2001. I was one of the very first researchers in the world to identify that ‘risk seeking behaviour’ is a key part of the presentation of many of these individuals, against a background of quite normal other psychological abilities and investigations including brain neuroimaging scans.

‘You need to break eggs to make an omelette’ is one formulation of the notion that you have to be able to make mistakes to achieve an overall goal. That particular sentence is, for example, used to convey the way in which you might have to put up with ninety nine turkeys before striking gold with one truly innovative idea. ‘Nothing ventured nothing gained’ is another slant of a similar idea. Interestingly, this phrase is often attributed to Benjamin Franklin. Franklin has an established reputation of his own as a ‘conceptual innovator‘.

It’s also a very interesting policy document on risk in dementia from the UK Department of Health, from 10 November 2010, a really useful contribution. This guidance was commissioned on behalf of the Department of Health by Claire Goodchild, National Programme Manager (Implementation), National Dementia Strategy. The guidance was researched and compiled by Professor Jill Manthorpe and Jo Moriarty, of the Social Care Workforce Research Unit, King’s College London.

Prof Alistair Burns, England’s clinical lead for dementia, has written a very focused and relevant Foreword to this piece of work. Here Alistair is, pictured with me earlier this week at the Dementia Action Alliance Annual Conference hosted in Westminster, London (“DAA Conference”). The event was a positive celebration of the #DAACC2A, “Dementia Action Alliance Carers’ Call to Action”, which embodies a movement where, “carers are acknowledged and respected as essential partners in care, and are supported with easy access to the information and the advice they need to assist them in carrying out their role.”

Risk enablement, or as it is sometimes known, positive risk management, in dementia involves making decisions based on different types of knowledge. However, people living with dementia and caregivers, quite often an eldest child or spouse, can handle risk in different ways. I feel that understanding living well with dementia is only possible through understanding the background to a person living with dementia, and his or her interaction with the environment. I’ve indeed written a comprehensive book on it, and I am in the process of writing a second book on it, which brings under the spotlight many of the key stakeholders, I believe, who contribute to “dementia friendly communities”.

Risk enablement is based on the idea that the process of measuring risk involves balancing the positive benefits from taking risks against the negative effects of attempting to avoid risk altogether. For example, the report cites the example of the risk of getting lost if a person with dementia goes out unaccompanied needs to be set against the possible risks of boredom and frustration from remaining inside. There are clearly various components of risk which might affect a person living with dementia. Risk engagement therefore becomes a constructive process of risk mitigation, an idea highly familiar to the law and regulation through the pivotal thrust of ‘doctrine of proportionality‘, that legislation must be both necessary and proportionate.

Risk enablement, it is argued, goes far beyond the physical components of risk, such as the risk of falling over or of getting lost, to consider the psychosocial aspects of risk, such as the effects on wellbeing or self-identity if a person is unable to do something that is important to them, for example, making a cup of tea. Therefore, the report proposes that “risk enablement plans” could be drawn up which summarise the risks and benefits that have been identified, the likelihood that they will occur and their seriousness, or severity, and the actions to be taken by practitioners to promote risk enablement and to deal with adverse events should they occur. These plans need to be shared with the person with dementia and, where appropriate, with his or her carer or caregiver. Thus advancing the policy construct of ‘personalisation’ offering choice and control, risk assessment tools are envisaged by the authors to help support decision making, and should include information about a person with dementia’s strengths and of his or her views and understanding about risk. Risk could apply to making a cup of tea, or going for a walk. We know that people living with dementia handle risks in different ways. For some people, a person living with dementia excessively walking beyond a local jurisdiction might be a known problem. For all the different causes of dementia medically, and for all the different ways in which individuals react to a dementia at different stages of the condition, a person can live with dementia in a sharply distinctive way.

Risk therefore in a hugely meaningful and substantial way has moved away from the “safety first” circles? And it fundamentally will depend on how an unique person living with his or her dementia embraces the environment in reality.

The idea that you need risk to live well with dementia is brought into sharp focus here by Chris Roberts, a friend of mine, speaking at the DAA Conference. I have recently begun to take risks in a highly enjoyable game for my #ipad3, which Chris indeed introduced me to, called, “Real Racing 3″. Here, Chris also talks about the crass way in which he was originally told his diagnosis, and lack of information about his condition given at the time of diagnosis. Therefore, Chris, I feel, brings into sharp focus a number of problem areas, which hopefully Baroness Sally Greengross and colleagues will address in a new five year strategy for England for 2015-20.

Is there more to influencing English dementia policy than putting up a poster?

Now is the time to influence the new English dementia strategy. It is critically important that the informed opinions of a diverse group of stakeholders are involved in framing this policy.

As with any strategy document, it will be hard to be in full control of all of the facts and evidence, but I feel it’s very important that the views of people living with dementia are taken into account. This is not just a case of ‘involving’ people living with dementia where possible. It’s a case of allowing people living with dementia to lead in framing the narrative. I am not going to suggest what these topics might be. I think, for people with more advanced dementia, it is going to be important to listen to the views of carers, both unpaid and paid. There is currently a huge policy problem that the needs of carers themselves are unaddressed. Carers need to be better supported in a more structured way.

There has also been a problem rumbling on years: that people who’ve received a diagnosis of dementia are not signposted to appropriate services. While the job description of ‘dementia adviser’ was mooted, I don’t feel this goes nearly enough. The ‘Dementia Challengers’ website, through amazing personal efforts from its one-person designer who has personal experience of this field, offers useful leads on support for making informed choices for living well with dementia. There is no escaping the overwhelming desire, also, to see a system of specialist nurses participating in a care system. Also, we are not making use of the substantial expertise of social work professionals. For issues such as advocacy over capacity and liberty, there are certain people with dementia who need to have equitable access to such resources.

I am a card-carrying signatory that each person living with dementia has an unique experience. I’ve even written a book on it. But it might help people with certain types of dementia to be reassured that there are clinicians with expertise in dementias, and can promote certain support groups (such as the excellent PPA Support Group). We need any diagnosis of dementia to be correct. I too often hear of people being given a diagnosis from somewhere, on the basis of a very scanty work-up. I understand the concerns that too many people are being denied of a correct diagnosis, but we must ensure that this part of the system is adequately resourced. It is possible there will be a breakthrough in drug development for the dementias in the near future. I wish the people working on this well. I am sure that they will not wish resources to be diverted disproportionately into this away from current care, or making it appear that the current living well of people with dementia is less of a priority?

The ‘dementia friendly communities’ policy plank is potentially fruitful. However, I think we should address how we hear a lot from corporates, but not much, in this jurisdiction, from professionals and practitioners who could be useful members of that community. Under the current legislative framework, both in domestic and international law, the rules of equality and human rights apply. These are not issues only for the ivory towers. They have direct relevance to the person with younger onset dementia who finds himself in an unfair dismissal situation. They also have relevance to the person in the badly run care home who feels (s) he is subject to “degrading treatment”. Access to the law has been a real setback for the current Government, as has been access to see your GP. These create the perfect storm for a ‘dementia unfriendly community’.

I am the last person to denigrate the efforts of the vast army of people putting up posters, signing petitions, or handing out leaflets, in the name of ‘dementia awareness’. There is a huge danger that these posters, petitions and leaflets send out a message of ‘mission accomplished’, if there is no follow up? But I am likewise a bit burnt that the fact that #G7dementia and “Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge” appeared from nowhere, and had the effect of threatening plurality in the dementia third sector. I am concerned about this, and now is the time to make views known to the Baroness Sally Greengross, Chair of the All Party Parliamentary Group, Prof Alistair Burns, the clinical lead for dementia in England, and Prof Martin Rossor, lead for research for dementia for NIHR.

Why two’s company, and three’s a very good thing, for English dementia policy

There’s an old-fashioned idea that the only relationship which matters is the one between the person living with dementia and the medical Doctor. I completely sympathise with the concern surrounding the idea ‘we are all patients now’, where, for example, people experiencing memory problems as a natural part of ageing get overmedicalised as ‘dementia’, perhaps for the purpose of hitting a national target: that well people are in fact the undiagnosed ones. But, likewise, my own experience as a person living with physical disability is that we are all persons who become patients at the point of becoming ill. I therefore think the term ‘patient leader’ is outdated, unless there is a specific group of people who only consider themselves ill.

I am not a ‘believer’ that I belong in an interconnected world by virtue of the fact that I have a Facebook account, but I do feel part of a wider network of knowledge, behaviours and skills. I feel that I can draw on this talent if I need support in me living independently, or care if I have unaddressed needs. When I could barely speak and move, soon after my meningitis, I was helped by a carer who is in fact to this day is one of my best friends. For too long, carers, I feel, have been airbrushed out of the picture. The clue is in the name ‘Whole Person Care’. Carers matter, and they should be given the prestige and status they so strongly deserve.

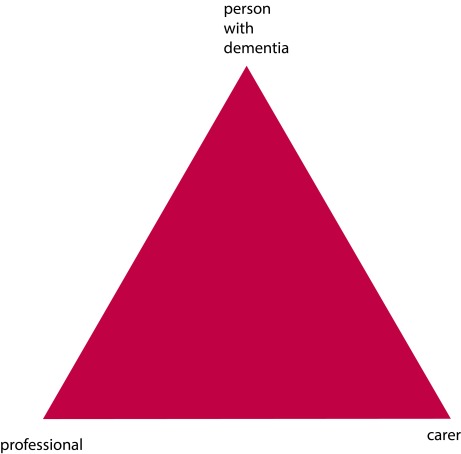

The landscape is though gradually changing, for the better. The “Triangle of Care” describes a therapeutic relationship between the person with dementia (patient), staff member and carer that promotes safety, supports communication and sustains wellbeing (Carers Trust, 2013). Carers often report that their wish to be effective often compromised by failures in communication, possibly because some people are unwilling listen.

At critical points, carers can be excluded by staff, and requests for helpful information, support and advice are not acted upon. Sadly we need to address the fact that medical professionals need specific training in working with carers, not working against them. This needs to include training in communication strategies with people with dementia, thus enabling people with dementia to be engaged for as long as possible.

redrawn from Carers’ Trust [Triangle of Care]

We currently have a dearth of research of this triangular relationship – but plenty on the ‘dyadic’ relationship between professional and carer. Most studies on patient–physician relationships and communication have focused on the dyadic interaction between the parties and the type of exchanges occurring among them. However, up to 60 percent of medical encounters involving elderly persons are threesomes (Adelman, Greene and Charon, 1987). The features of such relationships differ fundamentally from those of a dyad. The very presence of a third person may affect the basic patient–physician relationship (Kealy and Nolan, 2003) negatively by limiting patients’ involvement and assertiveness or actual exclusion from the care discussions (Greene et al., 1994), or positively by enhancing physician–patient communication and consequently superior comprehension and involvement by accompanied rather than unaccompanied patients (for example Clayman et al., 2005).

A person coming into contact with the health and care services currently do so from the point of a possible diagnosis. Results from the study from Zaketa and Carpenter (2010) were also actively seeking evaluation of their cognition and were subsequently diagnosed relatively early in their disease progression appear to suggest that physicians do not utilise patient-centered behavious such as emotional rapport building at first. Only once patients and caregivers are experiencing and demonstrating overt distress associated with more severe symptoms, or as physicians are delivering more dire news regarding the patient’s prognosis and ability to live independently, does a three-way relationship begin to kick in. Hubbard and colleagues (Hubbard et al., 2009) had concluded that carers are involved in treatment decision-making in cancer care and contribute to the involvement of patients through their actions during, before and after consultations with clinicians. Carers can act as funnels for information from patient to clinician and from clinician to patient. They can also act as facilitators during deliberations, helping patients to consider whether to have treatment or not and which treatment.

And English dementia policy can learn usefully not only from cancer. In paediatrics, De Civita and Dobkin (2009) revisited the term “triadic partnership”, in referring to “the therapeutic triangle in medicine that includes the caregiver, child, and medical team in facilitating adherence to treatment”. Optimal health, one may argue, is achieved when patients, caregivers, and health care providers collaborate in designing a manageable treatment program (Rapoff, 1999). This in time may impact on the policy for self-care. According to Strachan and colleagues, a better understanding of the individual factors that influence heart failure self-care is necessary for interventions to be more responsive to the needs and preferences of patients (Strachan et al., 2013). Individual factors known to affect heart failure self-care are thought to include the individual’s ability to manage comorbid conditions, depression or anxiety, sleep disturbances, age/developmental issues, levels of cognitive function, and health literacy (Riegel et al., 2009). But people are increasingly cognisant of the milieu of the effects of other agents.

The purpose of the analysis by Dalton (2002) is to describe the construction and initial testing of the theory of collaborative decision-making in nursing practice for a triad. The inclusion of a third person (family caregiver) in the theory required the addition of concepts about the caregiver, coalition formation, and nurse and caregiver outcomes. And other groups of patients can also helpfully inform on this debate. Patients themselves are increasingly been seen as critical ‘partners in care’. Hirsch and colleagues have outlined reasons why partners-in-care approaches are important idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, including the need to increase social capital, which deals with issues of trust and the value of social networks in linking members of a community (Hirsch et al., 2013).

I feel the answer comes not through dyads or triads, but by considering whole networks of care for the whole person. As observed elsewhere, although each professional group (e.g. nursing, neurology, physiotherapy) makes its own assessment of the needs of the patient, it appears that it is the integration of the assessment and service delivery that is perceived to be the most useful method to address the health-care needs of these patients (McCabe, Roberts and Firth, 2008). And there’s no doubt for me that this involves effective verbal and non-verbal communication all round.

Primary care visits of patients with dementia of the Alzheimer type (DAT) often involve communication among patients, family caregivers, and primary care physicians (PCPs). The objective of the study by Schmidt and colleagues was to understand the nature of each individual’s verbal participation in these triadic interactions (Schmidt, Lingler and Schulz, 2009). Caregivers of DAT patients and PCPs maintain active, coordinated verbal participation in primary care visits while patients participate less.? Interestingly, the caregivers’ verbal participation in triadic interaction was found to be also related to their reports of satisfaction with the primary care visit, specifically their satisfaction with interpersonal treatment of the patient with DAT by the PCPs. The literature is becoming, however, increasingly vigilant of the cautions in observing patient satisfaction as the outcome for a clinical consultation. In a study from Sakai and Carpenter (2011), videotapes of dementia diagnosis disclosure sessions were reviewed to examine linguistic features of 86 physician–patient–companion triads. Verbal dominance and pronoun use were measured as indications of power. Physicians dominated the conversation, speaking 83% of the total time. Evaluating patient expectations and preferences regarding physician communication style may be the most effective way of promoting patient-centered healthcare communication. To explore and gain further insight into the nature of the triadic interaction among patients, companions and physicians in first-time diagnostic disclosure encounters of Alzheimer’s disease in memory-clinic visits were studied by Karnieli and colleagues (Karnieli-Miller et al., 2012). Twenty-five real-time observations of actual triadic encounters by six different physicians were analysed, The authors found that an effective and empathic management of a triadic communication that avoids unnecessary interruptions and frustrations requires specific communication skills (e.g., explaining the rules and order of the conversation).

This is why feel two’s company, and three’s a very good thing, for English dementia policy. But I feel that wider networks at large are going to be proved to be important for whole person care, though some agents may possibly be more significant than others.

References

Adelman, R.D., Greene, M.G., Charon, R. (1987) The physician–elderly patient–companion triad in the medical encounter: the development of a conceptual framework and research agenda, The Gerontologist, 27, pp. 729–34.

Carers Trust (2013) The Triangle of Care, Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice in Mental Health Care in England, Second Edition (812 KB) http://static.carers.org/files/the-triangle-of-care-carers-included-final-6748.pdf

Clayman, M.L., Roter, D., Wissow, L.S., Bandeen-Roche, K. (2005) Autonomy-related behaviors of patient companions and their effect on decision-making activity in geriatric primary care visits, Soc Sci Med, 60, pp. 1583–91.

Dalton, J.M. (2003) Development and testing of the theory of collaborative decision making in nursing practice for triads, J Adv Nurs, Jan, 41(1), pp. 22-33.

De Civita M, Dobkin PL. Pediatric adherence as a multidimensional and dynamic construct, involving a triadic partnership. Pediatr Psychol. 2004 Apr May;29(3):157-69.

Greene, M.G., Majerovitz, S.D., Adelman, R.D., Rizzo, C. (1994) The effects of the presence of a third person on the physician–older patient medical interview, J Am Geriatr Soc, 42, pp. 413–9.

Hirsch, M.A., Sanjak, M., Englert, D., Iyer, S., Quinlan, M.M. (2014) Parkinson patients as partners in care. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014 Jan;20 Suppl 1:S174-9.

Hubbard, G., Illingworth, N., Rowa-Dewar, N., Forbat, L., Kearney, N. (2010) Treatment decision-making in cancer care: the role of the carer. J Clin Nurs. 2010 Jul;19(13 14):2023-31.

Karnieli-Miller, O., Werner, P., Neufeld-Kroszynski, G., Eidelman, S. (2012) Are you talking to me?! An exploration of the triadic physician-patient-companion communication within memory clinics encounters, Patient Educ Couns, Sep, 88(3), pp. 381-90.

Keady, J., Nolan, M. (2003)The dynamics of dementia: working together, working separately, or working alone? In: Nolan MR, Lundh U, Grant G, Keady J, editors. Partnerships in family care: understanding the care-giving career. Buckingham: Open University Press, p. 15–32, 2003.

McCabe, M.P., Roberts, C., Firth, L. (2008) Satisfaction with services among people with progressive neurological illnesses and their carers in Australia, Nurs Health Sci, Sept, 10(3), 209-215.

Rapoff, M. A., Lindsley, C. B., Christophersen, E. R. (1985). Parent perceptions of problems experienced by their children in complying with treatments for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 66, pp. 427–429.

Riegel, B., Moser, D.K., Anker, S.D., Appel, L.J., Dunbar, S.B., Grady, K.L., Gurvitz, M.Z., Havranek, E.P., Lee, C.S., Lindenfeld, J., Peterson, P.N., Pressler, S.J., Schocken, D.D., Whellan, D.J., American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; American Heart Association Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. (2009) State of science: promoting self care in persons with heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, Circulation, 120, pp. 1141e63.

Sakai, E.Y., Carpenter, B.D. (2011) Linguistic features of power dynamics in triadic dementia diagnostic conversations. Patient Educ Couns, Nov, 85(2), pp. 295-8.

Schmidt, K.L., Lingler, J.H., Schulz, R. (2009) Verbal communication among Alzheimer’s disease patients, their caregivers, and primary care physicians during primary care office visits, Patient Educ Couns, Nov, 77(2), pp. 197-201.

Strachan, P.H., Currie, K., Harkness, K., Spaling, M., Clark, A.M. (2014) Context matters in heart failure self-care: a qualitative systematic review, J Card Fail, Jun, 20(6), pp. 448 55.

Zaleta, A.K., Carpenter, B.D. (2010) Patient-centered communication during the disclosure of a dementia diagnosis, Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen, 25(6), pp. 513 20.

Whole person care, not misleading campaigning, will be brilliant for dementia

I believe that whole person care, to be introduced by the next Labour government, will be brilliant for bringing together health and care professionals with persons with dementia, and carers and support workers. But we should also be extremely vigilant of dodgy presentation of evidence being used ‘in the name of’ campaigning for my pet subject, dementia, I feel.

We keep on being told that the ageing population is one reason why we can no longer afford the NHS.

The clinical syndrome of dementia, for which advanced age is a risk factor, has therefore taken on a special significance in this context. Health policy gurus and politicians are seemingly having to find increasingly elaborate ways to force their agendas on an unsuspecting public. “The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism” (2007), penned by the Canadian author Naomi Klein, argues that libertarian free market policies have risen to prominence in some developed countries because of a strategy by some political leaders. These leaders deliberately exploit crises to push through controversial exploitative policies while citizens are too emotionally and physically distracted by these crises to mount an effective resistance. Crises are, though, useful instruments for bringing about change.

Within the timescale of this parliamentary term, the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge (launched in 2012) has seen a torrent of newspaper headlines with sensational memes. They invariably depict some sort of crisis in projected numbers of people with dementia, and have helped Big Pharma with the task of campaigning for increased funds to find ‘a cure for dementia’. The memes have largely had twangs of crises. For example, ‘dementia is the “next time bomb”‘ was an early news story from 7 May 2012. This messaging has continued consistently since, with the latest popular meme being “soaring numbers diagnosed with dementia“. Indeed, only recently with the arrival of the “Dementia UK (second edition) report” presented in a conference in Central London, a press release was published stating “Alzheimer’s Society calls for action as scale and cost of dementia soars”. But this messaging has caused utter confusion and resentment amongst leading academics and practitioners in dementia. The cumulative effect, instead, of such headlines and articles in public health has been to produce a feeling of ‘moral panic‘. As rightly pointed out by Dr Martin Brunet in “Pulse Magazine”, a well respected commentator on dementia policy in English primary care, recent evidence suggests rather that that the prevalence of dementia in over 65s in 2011 is lower than would have been expected. This “CFAS-II study” from Cambridge, which was published last year in the Lancet, is widely quoted, comprehensively peer-reviewed, and is extremely well known amongst people working in this field.

This is all incredibly self-defeating, as the “Prime Minister Dementia Challenge” was intended to bring greater awareness of the dementias amongst the general public not least to tackle the stigma faced by people living with dementia in their everyday lives. But you have to wonder what the intention of this approach is in the long term? The final report from the Commission on the Future of Health and Social Care in England (“Barker Commission”) was published on 4 September 2014. It discusses “the need for a new settlement for health and social care to provide a simpler pathway through the current maze of entitlements”. Labour intends to introduce ‘whole person care’ in the next parliamentary term, and it could be that this “scorched earth” approach for dementia has served a useful function. “Whole person care” is their new “big idea“. The Barker Commission recommends moving to a single, ring-fenced budget for the NHS and social care, with a single commissioner for local services.

On page 9 of their final report, the ‘ultimate star prize’ is described, the personal budget:

“Personal budgets, and care in hospital and out of it, would be provided from a single, ring-fenced budget. There would be one budget and one commissioner for individuals and their families to deal with, in place of health, social care and, in the case of those aged over 65, the Department for Work and Pensions. Commissioners would be freed to acquire care designed around an individual’s need for support and health care, largely dissolving the current definitions of what is a health need and what is a care requirement.”

And this of course is nothing new: it has been in gestation for quite some time. I myself, in fact, wrote about personal budgets for ‘Our NHS’ in my piece ‘Shop til you drop?’ on 4 September 2013. It is said that Andy Burnham MP, Shadow State of Secretary of Health, “welcomes the Barker Commission“, but one wonders whether he wishes openly to support the more unsavoury parts. Labour is desperately keen to introduce its policy changes on integrated care, without them being seen as another “top down reorganisation”. Any public resistance to their flagship policy will be political dynamite. Labour is instead currently campaigning on an anti-marketisation and anti-privatisation slate, and has pledged to repeal the highly toxic Health and Social Care Act (2012) (“the Act”).

One significant part of this repeal will be the abolition of “section 75″ and its associated regulations, which introduced competitive tendering in commissioning as the default option for NHS procurement. Nevertheless significant faultines in policy, described elegantly by Prof Calum Paton in his pamphlet “At what cost? Paying the price for the market in the English NHS” for the Centre for Health and Policy Interest (February 2013), still exist. They also are at danger of persisting, even if Labour triumphantly repeals the Act. There is a danger that unless these other pro-marketisation strands are addressed first, such as the purchaser-provider split, the “whole person care” policy will become engulfed in an intensely neoliberal direction. The counterfoil to this from Labour would presumably be that whole person care does not require a market in the first place. For this, clearly, Labour must not inflict personal budgets. A further big concern of mine is simple: not only will current scientific research into dementia have been completely misrepresented in the popular press, but also the field of dementia will be used to provide the raison d’être for yet another upheaval in service change.

And that upheaval could witness yet another change from the founding principles of the NHS. It could also be one too many.

Presentations by Shibley Rahman at the Alzheimer Europe conference 2014 on autonomy and dignity

This year’s Alzheimer Europe conference is on ‘Autonomy and dignity’ between 20-22 October 2014.

I think it is timely that this conference is taking place at this important stage of the development of English national policy.

The direction of travel is a fully integrated health and care system, where people are signposted to information quickly and can make appropriate decisions.

The person living with dementia must come first; but we are also moving to a situation where a number of different people, such as friends, family, unpaid caregivers, paid carers, social care practitioners or nurses, might help to influence a personal care plan.

Ideally, a person living with dementia will be given in the future good care and support, in accordance to his or her known wishes, from the point at which a correct diagnosis is made.

Autonomy is part of the medical construct for ethical behaviour; beneficence, justice and non-maleficence are critical too.

With the ideal of autonomy, it’s vital that no ‘coercion’ takes place for people with dementia who are able to make autonomous decisions.

There should never be an illusion of people living with dementia where they are able to make decisions, when those decisions are clearly made on their behalf.

Dignity is pivotal to all dementia policy in England, and the law must be robust in safeguarding vulnerable people too.

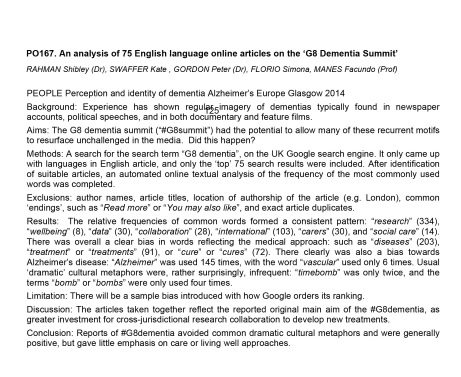

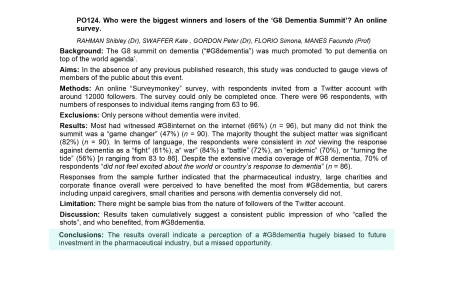

I am looking forward to presenting two posters on language and the perception of #G7 dementia.

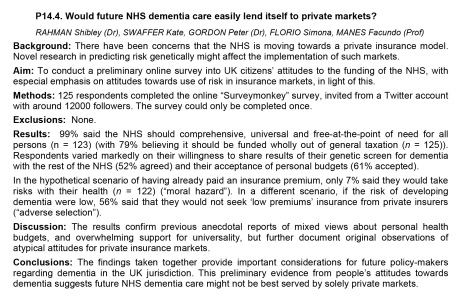

I am also privileged in that I have been chosen to present one of the few oral presentations. I am doing on this on the future of healthcare systems for dementia in England, arguing that policy aims, in particular universality and equity of access, will not be satisfied from a private insurance market.

I will be joined by my close friends Jayne Goodrick and Chris Roberts.

[photo by kind permission of Chris R]

Please feel free to consider the research I’ll be presenting on behalf of myself, Kate Swaffer (living with a dementia and student at the University of Wollongong), Dr Peter Gordon (Consultant Psychiatrist), Simona Florio (Healthy Living Club, Stockwell), and Prof Facundo Manes (Chair of Behavioural Neurology, University of Favorolo, Buenos Aires; Co-Chair for research in dementia and aphasias for the World Federation of Neurology).

Private markets vs universality (oral presentation)

Language used in media presentation of the main #G7dementia event held in London

Perceived functions of #G7dementia

The time is now right to promote specialist nurses in ‘dementia friendly communities’

There was a time when the GP used to be at the heart of a person’s community, as well as ‘delivering care’. For some people, there is no such thing as society, and the community consists of high street brands, banks and services (such as police or fire).

I’ve spent some time thinking about the implementation of the ‘dementia friendly community’ policy in a number of jurisdictions. It really has struck me how, for whatever political reasons, nurses are not perceived to be the heart of dementia friendly communities in England.

This, I feel, is a great tragedy. I don’t deny there are about a hundred different causes of a dementia, people’s social circumstances will differ (it is not uncommon for a female widower to develop a dementia while very lonely), cultural differences exist (for example in the rôle of the family in those of an Asian background), there are different rates of progression, and so on.

On receiving a diagnosis, I think support services in dementia should be much stronger than now. What is all too commonplace is a travesty. People don’t know where to turn to for basic information about clinical aspects, or wider aspects about living in the community.

As the dementia progresses, in the later stages, a focus will be to keep the person out of hospital wherever possible. Clearly, support and care in the community need to be funded properly.

A ‘crisis’ for a person living with dementia is where a ‘stressor’ causes that person no longer to be able to cope with living in his or her usual environment. There could be a number of causes of that, but it’s noteworthy that many of them are in fact medical. I disagree a specialist nurse in dementia is necessarily a job for a community psychiatry nurse (“CPN”), as the workload of such nurses tends to be very big.

But seeing a rôle for a CPN is not a trivial one, as I’m a fully signed up devotee of ‘parity of esteem’ where mental health is not seen as the ugly sister of physical health. For that matter, social work practitioners, who often find themselves at the heart of mental capacity decisions and safeguarding issues, should be on an equal footing too with other professionals.

I said to Chris, a friend of mine living well with dementia recently, “GPs will even be in a good position to coordinate information”.

I was in fact repeating words from a GP.

Chris, “So why don’t they?”

In certain respects, in designing a system you wouldn’t wish to start from here.

Without the focus on ‘budgets’ which do not necessarily deliver the ‘right kind’ of choice for the person with the health and care matters, it’s important that people with dementia have rights to a personal care plan, which is responsive to that person’s needs in real time. Knowing someone’s background is particularly essential in people with Alzheimer’s disease where longer term memories may be more intact. Knowing someone as a person is of course at the heart of personhood, through maybe a ‘life story’.

I don’t think it should be a ‘luxury’ of people with dementia following them after diagnosis through the system. I think, in fact, it should be an essential aspiration. It’s really important that somebody can cross off inappropriate medications, such as perhaps antipsychotics, on a drug chart if the person with dementia might not benefit.

It might help if a dementia specialist companion could spot problems in overmedicated people for blood pressure, for example. These individuals might become at risk of falls (and subsequent bone fractures if living with osteoporosis). Or somebody may be developing constipation or a stinging urine, becoming acutely confused. Dementia is not simply caused by conditions of old age, but frail individuals can do particularly bad when coming into contact with hospitals.

In the scenario that a person with dementia at any stage does need to go into hospital, it would help enormously if there could be continuity of care between the community and hospital. People with all types of dementia can find unfamiliarity, in people and environments, extremely mentally distressing, and this can be detrimental to their physical health (taking a whole person care approach). There are few people better than paid carers, with pay above the national minimum wage, and not on zero hour contracts, and unpaid caregivers including friends and family, to inform on these care plans, but the person living with dementia is the one for whom the plan is being designed.

All staff clearly need to be informed and skilled about dementia, and it is vital that resources are put aside for the adequate training of the workforce. The workforce themselves want this.

It won’t be a surprise to you to learn that I see specialist nurses in prime position to offer a huge deal to the implementation of whole person care for dementia from the next Government?

I think my views are broadly consistent with a number of places. A number of reports across jurisdictions have been important in establishing the direction of travel for acute hospital care: e.g. “Dementia care in the acute hospital setting: issues and strategies: a report for Alzheimer’s Australia” (Alzheimer’s Australia, June 2014), “Spotlight on dementia care: a Health Foundation Improvement Report” (Health Foundation, October 2011), and the Royal College of Nursing’s report “Commitment to the care of people with dementia in hospital settings” (RCN, January 2013).

Examples of appropriate clinical leads, as the RCN themselves recognise, are “Admiral nurses” from the charity @DementiaUK, Alzheimer Scotland dementia specialist nurses, dementia champions in Scotland, and ward champions. Merely having ‘dementia advisors’ will be a case of the bland and ill informed leading the bland, on the other hand.

Like many other ‘once in a lifetime opportunities’, if we get this right the service could be vastly improved. I am confident that, if given the proper funding to make this happen, and strong leadership cascades downwards, the next Government will rise to this challenge.

Trivialising dementia – too much inappropriate rocking of the boat?

When I wrote my highly successful book, “Living well with dementia”, using the phrase deliberately from the 2009 English dementia strategy document for England, I never knew the phrase was being bastardised so much for often very trivial initiatives in dementia.

On the other hand, I had huge delight in seeing its immediate relevance to a carers’ support group I went to last week.

I feel deeply hurt that the serious issues in my book, such as advocacy for mental capacity, the presentation of the cognitive neurology of the dementias, or the use of ambient-assisted technology have not been widely discussed amongst the wider community.

In that, I feel the book has failed.

I welcome proposals for the next Government to maximise money into actual service, and to re-establish health funding in line with other comparator countries.

Commissioning in dementia is now not based on what is best for the person for the person with dementia, but what is best for your Twitter commissioner friends.

I look forward to the Health and Wellbeing Boards playing a pivotal rôle in establishing some sort of normality for what commissioning in living well with dementia might be as a value-based outcome.

The strangehold of “shiny”, “off the shelf” “innovative packages”, in the drive for the current Government to ‘liberalise’ the financial market in dementia has acted for a cover for disturbing, unacceptable cuts in dementia service provision in the last few years.

I remember ‘boat rocking’ the first time around from the elegant work of Prof Debra Meyerson.

I do not wish to promote frontline professionals, many of whom have spent seven years at least at medical school or in their nursing training, to become lambs to the slaughter in the modern NHS and social care.

Keeping it real, we know that real frontline professionals in medicine and social care, even if they are not in a downright toxic environment requiring whistleblowing, can find it dangerous being risk appetitive.

Indeed, being risk appetitive, while great for innovation and leadership, can literally be deadly for patient safety.

The next Government has enough on its hands with enforcing care home standards and sanctioning for offences against the national minimum wage for paid carers as it is.

We have to think for a second for the vast army of paid workers in the NHS, as well as the rather well paid people who like their shiny new boxes, I feel.

The schism between the social media and what is happening at service level I think is most alarming, and perhaps symptomatic about how the health and social care services have begun to work in reality.

All too often, I am having first hand experience of busy frontline nurses being dragged in front of entrepreneurs in their local dementia economy to hear shills beginning, “I don’t have first hand experience of caring in dementia, but…”, before the hard sell.

This is tragically being reflected on the world stage too, though I do anticipate that the G7 legacy event from Japan which is looking carefully at their experience with care and support post diagnosis, next year, will be brilliant.

It is important for leaders in dementia to have authenticity.

I have severe doubts and misgivings about what gives the World Dementia Envoy the appropriate background and training in dementia for him to be in this important post.

It is all too easy for ‘thought leaders’ in corporate-like medical charities to have no formal qualifications or training in medicine, nursing, or social care, and opine nonetheless about weighty issues to do with policy.

I am concerned that the global ‘dementia friendly communities’ policy plank appears to have been straightjacketed through one charity in England, when it is patently obvious that various other charities such as the Joseph Rowntree Foundation have made a powerful contribution.

The media have largely not engaged in a discussion about living well with dementia, but engaged simply with Dementia Friends or a story arising out of that.

I am alarmed about the lack of plurality in the dementia research sector.

I think the All Party Parliamentary Group (“APPG”) for dementia have done some valuable work, but their lack of momentum on specialist nurses including Admiral nurses, spearheaded by the charity Dementia UK, seriously offends me.

I am sick of how the notion of ‘involvement’ of people with dementia has been abused in service provision mostly, although I am encouraged very much by initiatives such as from DEEP and Innovations in Dementia.

I think there have been genuine improvements in engaging people with dementia in research, through a body of work faithfully peer-reviewed in the Dementia Journal looking at heavy issues such as the meaning of real consent.

I am now going to draw the line of tokenistic involvement of people with dementia to front projects without any meaningful inclusion.

And in fairness, this tokenistic involvement is, I am aware, happening in various jurisdictions, not just England.

All too often, “co-production” has become code for ‘exploitation’ rather than ‘active partnership’.

The prevalence of dementia is actually falling in England, it is now thought.

The ‘dementia challenge’ was our challenge to making sure that we adequately safeguarded against people rent seeking from dementia since 2012.

In that, I think we have spectacularly failed.

I am overall very encouraged, however, with the success of the huge amount of work which has been done, including from the highly influential Alzheimer’s Society, and from the communitarian activism of “The Purple Angels”.

All this ‘radicalism’ has taken on a rather ugly, conformist twang.

Now is though time to ‘take stock’, as Baroness Sally Greengross, the current chair of the APPG on dementia, herself advised, as the new England dementia strategy is being drafted ahead of the completion of the current one in March 2015.

Meeting the needs of persons with younger onset dementia and their supporters

There are many different types of dementia. I happen to believe it’s possible to live well with dementia.

That’s why I wished to travel to Robertsbridge from London Charing Cross to see Charmaine and family, and to give her a copy of my book which I had promised her.

“Living well with dementia” is also the name of the current (five year) dementia strategic framework for England, which is about to be renewed.

The ‘behavioural variant’ of frontotemporal dementia is normally a dementia which occurs in younger people (below the age of 65), with quite a subtle progressive change in behaviour and personality noticed by others.

Early on, in this condition, problems in short term memory and new learning are not in fact common, leading many persons with this dementia to score very highly on the MMSE screening test.

Meanwhile, the ‘temporal variant’ of frontotemporal dementia encompasses several different subtypes.

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA), one of these subtypes, is a language disorder that involves changes in the ability to speak, read, write and understand what others are saying. It is usually acknowledged to be properly described by Mesulam.

Problems with memory, reasoning, and judgment are not thought to be usually apparent at first, but can develop over time.

It is associated with a disease process that causes atrophy in the frontal and temporal areas of the brain, and is distinct from aphasia resulting from a stroke.

In 2011, criteria were adopted for the classification of PPA into three clinical subtypes: nonfluent/agrammatic variant PPA, semantic variant PPA and logopenic variant/phonological PPA.

Therefore the frontotemporal dementias are not usually, early on, characterised by problems in memory for events and facts.

PPA can, as it progresses, be accompanied with anxious behaviours manifest as obsessive-compulsions.

The ‘Dementia Research Centre’ (part of University College London, to which the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery and Institute of Neurology are associated or attached) hosts a number of superb support groups.

The PPA Support Group holds a number of support groups at regular time intervals. Their newsletter from August 2014 is here.

The convener is Jill Walton, at jill.walton@ftdsg.org.

I attended yesterday’s meeting.

My close #Twitter pal Charmaine, @charbhardy (Charmaine Hardy), invited me down to Robertsbridge, East Sussex, for Wednesday September 17 2014 from 12 noon to 2pm.

Charmaine describes herself as “I’m a carer to a husband with PPA dementia.”

Of course, Charmaine, her husband and me were in attendance as part of this impressive group of twelve delegates.

Charmaine also claims “Love my garden I post too many pics.” I disagree though on the latter half – Charmaine never posts too many pics of her garden. Here is a photograph I took of a very beautiful flower of hers.

This is in fact the pergola Charmaine’s husband built with Paul.

The meeting was held in one of the venue rooms at The Ostrich Hotel (“The Ostrich”), Station Road, Robertsbridge, East Sussex, T 32 5DJ.

The Ostrich is an outstanding B&B housed in a gorgeous Victorian location, with a spectacular tropical garden.

I had the pleasure of sampling a delicious supper with Charmaine and her husband.

Our couple of hours yesterday was an informal meeting for people affected by a diagnosis of PPA, their family and friends. We all thought the meeting was fantastic.

Jill showed a video for teaching purposes of what the language presentations of dementia, including PPA, are broadly like.

We all participated in an activity where we had to express the meaning of a sentence without using any of the words, e.g. “Part of my leg is hot and painful.” It was difficult!

The meeting was very enjoyable, but we were able to discuss many issues.

We discussed how the diagnosis of dementia could mean a contraction of your friends’ network, leading to loneliness.

We also discussed how greater education of what the dementias are would help to overcome stigma and discrimination against people living with dementia.

Overall, the feeling of the group was each person living with dementia must be treated with dignity as an unique individual with a significant past and present.

We also felt that the ‘one glove fits all’ approach of housing and accommodation doesn’t work, and forcing people with dementia into accommodation solutions they’re not happy with is bound to cause distress.

This can be a particular problem with younger patients with dementia, who wish to lead independent lives as long as possible, not wishing to be forced into an old people’s home.

If a younger person who receives a diagnosis of dementia it can be challenging to deal with your employer; the construct of ‘dementia friendly communities’, which is said to promote inclusivity, cannot adequately protect against unlawful discrimination if people are not aware of their legal rights and have inadequate access to justice.

PPA also has particular resonance in English policy as a noteworthy example of a younger onset dementia. A ‘younger onset dementia’ refers to a dementia which occurs before 65.

This cut-off is completely arbitrary, however (as arbitrary as the “retirement age”).

Younger onset dementia is a distinct group of people living with dementia, because the conditions which cause these dementias tend to be late presentations of “young” conditions or early presentations of “old” conditions.

In theory, the ‘younger onset dementia’ label is inaccurate, in that a dementia might start long before the symptomatic presentation of people with dementia. At one extreme, some people with the very rare genetic presentations of dementia are born with their dementias (or indeed have the genetic make-up in utero.)

It is therefore clear that we need a much greater sophistication in responding to the needs, beliefs, concerns and expectations of people with younger onset dementia.

The unique identity of people with younger onset dementia means that they have distinct research and service provision needs.

This is particularly true as some of the younger onset dementia can be accompanied by obvious movement and psychiatric symptoms, such as forms of prion disease (GSS and CJD) or Huntington’s disease.

A longstanding problem with the organisation of services is that mental illness problems have traditionally played ‘second fiddle’ to medical problems.

This is exacerbated by the drastic cuts in social care which have relentlessly continued in the last few years.

It is hoped that some of these problems in ‘parity of esteem’ might be mitigated against through ‘whole person care’, the expected policy from May 8th 2015 to integrate health and social care properly for the first time.

I had a very nice conversation with Fiona Chaâbane from the University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust.

Fiona’s rôle there is as a clinical nurse specialist in dementia, and as a clinical coordinator for Huntington’s disease and younger onset dementia.

I am hopeful that the ‘care coordinator’ rôle will be properly fleshed out in the next government, which will see a more substantial rôle for specialist and general nurses within networks comprising ‘dementia friendly communities’.

I feel that, in many of these conditions, cognitive or psychiatric features can be prominent early on.

My concern about the misdiagnosis of these dementias which do not have a strong component of a failure of memory is a very substantial one.

A misdiagnosis (e.g. of a dementia -> non-dementia such as anxiety or depression) can not only mean that person not obtaining the proper medical treatment, but can also mean that that person goes down a clinical pathway for which he or she is not appropriate. This can also impact on that person’s life and job in an utterly destructive way, particularly more so if before retirement age.

Thanks to Jill, Charmaine, her husband and the PPA support group for educating me properly about the dementias. It was particularly helpful to me too in confirming my concerns about research and service provision for the younger onset dementias in England, unfortunately. But at least we can now all begin to address them.