Home » Book

Courage and leadership in healthcare: a critical analysis

Rebecca Myers and I have been writing a book together for some time.

It’s called “Courage and leadership in healthcare: a critical analysis”. We are honoured that Sage Publications (Books), highly celebrated in this field, have agreed to publish our book in 2018.

Sage, of course, publish the journal “Dementia: the International Journal of Social Research and Practice.”

We hope that our book will find relevance to all health and social care professionals with a particular interest in management and leadership. We are actively looking for people who wish to volunteer to give a clear account of their experiences (such as – and this list is not exclusive and complete – difficulties in ‘speaking out’ against the system for example clinically in safe staffing or “blowing the whistle”, courage in raising issues about bad policy or conflicts of interest, courage in coping with public failure, courage in facing terrible standards in healthcare directly or as a close relative or friend, courage in scientific research, courage in dealing with personal loss of a loved one, courage in dealing with the illness of someone close).

We anticipate that the book will have a number of important aspects – and we want people who use the health and social care services, as well as people who work for and run services, to tell us what they think is important about what is being done right (and wrong).

Moral courage is the courage to take action for moral reasons despite the risk of adverse consequences.

Courage is required to take action when one has doubts or fears about the consequences. Moral courage therefore involves deliberation or careful thought.

The concept of moral distress is not new. Jameton (1984) offered the first definition of moral distress in the nursing literature. He stated that moral distress is the stress that occurs “when one knows the right thing to do, but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action” (p. 6).

Courage is also critical to people who run the NHS and social services. Lessons can be drawn from the leadership styles of people who have brought about exhibited great courage and brought about change, such as Gandhi or Martin Luther King.

Change is a powerful force in healthcare systems, and essential for healthcare systems to match provision to meet needs of patients and users.

Courage can be extremely personal too. Courage historically has been couched in the language of adversarial combat, and this runs in parallel with media messaging of conditions such as cancer or dementia. We will consider whether it is appropriate to consider cancer or dementia as a ‘fight’ – in that there are some cancers, for example, where complete remission is a possibility.

While anything can happen to anyone at any time, the preparation of death is important, for example, in palliative approaches; and has implications for individual reactions to life-changing illnesses and the lives of close carers.

Professionals and practitioners, and students, working in health and social care can get ill themselves too. Courage is needed to have to deal with multiple demands, such as the threats to health and illness themselves, the regulator, the media, impact on friends and family, and intense stigma and exclusion from peers and colleagues. (I hope to write about this from personal experience.)

The term “blow the whistle” has long been felt to be a strong phraseology for the courage to speak up against cultures which have gone wrong. Problems have still remained pursuant to the Public Interest Disclosure Act (1998) which is supposed to protect public sector employees. And yet speaking up courageously is often needed to promote patient safety, a key duty of all registrants in healthcare.

We will give an account of the individual experiences of people who have spoken out against the system, including misdiagnosis of important conditions, criticising poor clinical care, and speaking out against child abuse. Often people who speak out find themselves emotionally and intellectually ‘burnt out’ too, and the chapter will consider the pivotal need to protect staff wellbeing too.

Our book is a timely look at an important professional strand for all practitioners and professionals, patients and service users, and all other members of the general public. We hope you will help us get the content and style of the book right – and we hope especially you can directly contribute.

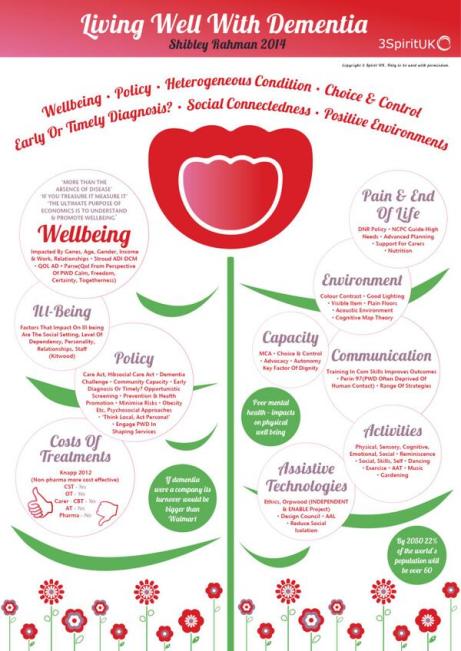

An overview of my book ‘Living better with dementia: champions for enhanced communities”.

I hope you find this overview of my book ‘Living better with dementia: champions for enhanced communities’ useful.

It is written by me.

And the Forewords are Prof Alistair Burns, the England clinical lead for dementia, Kate Swaffer (Alzheimer’s Australia, Dementia Alliance International, and University of Wollongong, Australia), Chris Roberts (Dementia Action Alliance Carers Call to Action, Dementia Alliance International), and Dr Peter Gordon (Consultant Psychiatrist in dementia and cognitive disorders, NHS Scotland).

It will primarily assess where we’ve got to, along with other countries, in improving diagnosis and post-diagnostic care, and assess realistically the work still yet to be done.

My thesis will articulate why the ‘reboot’ of the global “dementia friendly communities” must now take account of various issues to be meaningful. It will argue for a difference in emphasis from competitive ‘nudge’ towards universal legal and enforceable human rights promoting dignity and autonomy.

It will also argue that dementia friendly communities are meaningless unless there is a shift in the use of language away from ‘sufferers’ and ‘victims’, while paying tribute to the successful “Dementia Friends” initiative.

It will, further, argue that dementia friendly communities are best served by a large scale service transformation to ‘whole person care’, and provide the rationale for this. A critical factor for enhancing the quality of life of people living better with dementia will be to tackle meaningfully the social determinants of health, such as housing and education.

The thesis will also argue that dementia friendly communities must also value the behaviours, skills and knowledge of caregivers in wider support networks. This is essential for the development of a proactive service, with clinical specialist nursing input deservedly valued, especially given the enormous co-morbidity of dementia.

This title will be published by Jessica Kingsley Publishers, in early 2015.

Chapters overview

Chapter 1 provided an introduction to current policy in England, including a review of the need for a ‘timely diagnosis’ as well as a right to timely post-diagnostic care. This chapter also provided an overview of the current evidence base of the hugely popular “Dementia Friends” campaign run by the Alzheimer’s Society and Public Health England, to raise awareness about five key ‘facts’ about dementia. It was intended that this campaign should help to mitigate against stigma and discrimination that can be experienced by people living with dementia and their caregivers.

Chapter 2 comprised a preliminary analysis of stigma, citizenship and the notion of ‘living better with dementia’. This chapter explained the urgency of the need to “frame the narrative” properly. This chapter also introduced the “Dementia Alliance International” which has fast become a highly influential campaigning force by people living with dementia for people living with dementia.

Chapter 3 looked at the various issues facing the timely diagnosis and post-diagnostic support of people living with dementia from diverse cultural backgrounds, including people from black, Asian and ethnic minority backgrounds, people who are lesbian, bisexual, gay or transsexual, and people with prior learning difficulties.

Chapter 4 looked at the issue of how different jurisdictions around the world have formulated their national dementia strategies. Examples discussed of countries and continents were Africa, Australia, China, Europe, India, Japan, New Zealand, Puerto Rico and Scotland.

Chapter 5 looked at the intense care vs care debate which has now surfaced in young onset dementia, with a potentially problematic schism between resources being allocated into drugs for today and resources being used to fund adequately contemporary care to promote people living better with dementia. An example was discussed of how the policy of ‘Big Data’ had gathered momentum across a number of jurisdictions, offering personalised medicine as a further potential compontent of person-centred care. This chapter also considered the impact of the diagnosis of younger onset dementia on the partner of the person with dementia as well. A candid description was also given about the possible sequelae of the diagnosis of young onset dementia on employment, caregivers, and in social isolation.

Chapter 6 focused on delirium, or the acute confusional state, and dementia. It considered the NICE guidelines for delirium, and the pitfalls in considering the relationship between delirium and dementia in English policy.

Chapter 7 was the largest chapter in this book, and took as its theme care and support networks. An overview of how patient-centred care is different from person-centred care was given, and how person-centred care differs from relationship-centred care. The literature inevitably has thus far focused on the ‘dyadic relationship’ between the person with dementia and caregiver, but a need to enlarge this to a professional in a ‘triangle of care’ and extended social networks was further elaborated and emphasised. Finally, the importance of clinical specialist nurses in ‘dementia friendly communities’ was argued, as well as the Dementia Action Alliance’s “Carers Call to Action”. Different care settings were described, including care homes, hospitals – including acute hospital care, and intermediate care.

Chapter 8 considered eating for living well with dementia. This chapter considered enforceable standards in care homes, including protection against malnutrition or undernutrition. The main focus of the chapter was how people with dementia might present with alternations in their eating behaviour, and how the mealtime environment must be a vital consideration for living better with dementia.

Chapter 9 looked at a particular comorbidity, incontinence. The emphasis was on conservative approaches for living well with dementia and incontinence. Other issues considered were the impact of incontinence on personhood per se, and the possible impact on the move towards an institutional home.

Chapter 10 argued how the needs for people living better with dementia would be best served by a fully integrated health and social care service. This chapter provided the rationale behind this policy instrument in England. The chapter also considered various aspects of what would be likely to make ‘whole person care’ work, including data sharing, collaborative leadership, care-coordinators, responsible and accountable ‘self care’, and the multi-disciplinary team. This chapter also considered how it was impossible to divorce physical health from mental health and social care, and explained the intention of the longstanding drive towards ‘parity of esteem’ in English policy.

Chapter 11 considered the importance of the social determinants of health. A focus of this chapter was on education, and its impact on a person living with dementia. However, the main focus of this chapter was housing, including ‘dementia friendliness, downsizing, and green or public spaces.

Chapter 12 considered whether ‘wandering’ is the most appropriate term. The main emphasis of this chapter were the legal and ethical considerations in the use of ‘global positioning systems’ in enhancing the quality of life of persons with dementia and their closest ones.

Chapter 13 considered a number of important contemporary issues, with a main emphasis on human rights and “rights based approaches”. While there is no universal right to a budget, the implementation of personal budgets was discussed. The chapter progressed to consider a number of legal issues which are arising, including genetic discrimination in the US jurisdiction, dementia as a disability under the equality legislation in England, and the importance of rights-based approaches for autonomy and dignity. Finally, the issue of engagement was considered.

Chapter 14 was primarily concerned with art and creativity. This chapter took as its focus on how living with dementia could lead to art and creativity, and how the cultural needs of people living with dementia could best be furnished through laughter, poetry and art galleries or museums. This focus also looked at the exciting developments in our understanding of the perception of music in people living with dementia, and how music has the potential to enhance the quality of life for a person living well with dementia.

Chapter 15 looked at the triggering of football sporting memories in people living well with dementia. This chapter considered the cognitive neuroscience of the phenomenon of this triggering, and presented a synthesis of how the phenomenon could be best explained through understanding the role of emotional memory in memory retrieval, how autobiographical memories are represented in the human brain usually, the special relevance of faces or even smells such as “Bovril”.

Chapter 16 looked at the impact of various innovations in English dementia policy, giving as examples including service provision (such as the policy on reducing inappropriate use of antipsychotics or the policy in timely diagnosis) and research. This chapter also contemplated the principal factors affecting how innovations can become known, and what ultimately determines their success.

Chapter 17 looked at how leadership could be promoted by people living with dementia. This chapter considered who might lead the change, where and when, and why this change might be necessary to ‘recalibrate’ the current global debate about dementia. This chapter considered how change might be brought about from the edge, how silos might be avoided, the issue of ‘tempered radicals’ in the context of transformative change to wellbeing as an outcome; and finally how ‘Dementia Champions’ are vital for this change to be effected.

Please note that Beth is not endorsing this book – this image is entirely separate and is taken from the main event for G8 dementia – we’re all proud of Beth’s work meanwhile!

Journal references for my chapter on living well with dementia and urinary incontinence

I am yet to include influential blogposts, such as this one by Beth Britton (@BethyB1886).

But there is the core of my journal references which I intend to cite in my book chapter on living well with dementia and incontinence.

Please do let me know of any work, in whichever one of the media, you should like me to include. Very many thanks.

Abrams P, Blaivas J, Stanton S, Anderson J. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function.Scand J Urol Nephrol 1988;(Suppl 1)14:5–10.

Afram B, Stephan A, Verbeek H, Bleijlevens MH, Suhonen R, Sutcliffe C, Raamat K, Cabrera E, Soto ME, Hallberg IR, Meyer G, Hamers JP; RightTimePlaceCare Consortium. Reasons for institutionalization of people with dementia: informal caregiver reports from 8 European countries. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014 Feb;15(2):108-16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.09.012. Epub 2013 Nov 12.

Allan L, McKeith I, Ballard C, Kenny RA. The prevalence of autonomic symptoms in dementia and their association with physical activity, activities of daily living and quality of life. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22(3):230-7. Epub 2006 Aug 10.

Allen J, Oyebode JR, Allen J (2009) Having a father with young onset dementia: The impact on well-being of young people. Dementia. 8: 455-480.

Berrios G. Urinary incontinence and the psychopathology of the elderly with cognitive failure. Gerontology 1986;32:119–24.

Boustani MA, Sachs GA, Alder CA, Munger S, Schubert CC, Guerriero Austrom M, Hake AM, Unverzagt FW, Farlow M, Matthews BR, Perkins AJ, Beck RA, Callahan CM. Implementing innovative models of dementia care: The Healthy Aging Brain Center. Aging Ment Health. 2011 Jan;15(1):13-22. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2010.496445.

Brandeis GH, Baumann MM, Hossain M, Morris JN, Resnick NM. The prevalence of potentially remediable urinary incontinence in frail older people: a study using the Minimum Data Set. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997 Feb;45(2):179-84.

Brocklehurst J, Dillane J. Studies of the female bladder in old age II: cystometrograms in 100 incontinent women. Gerontol Clin 1966;8:306–19.

Campbell A, Reinken J, McCosh L. Incontinence in the elderly: prevalence and prognosis. Age Ageing 1985;14:65–70.

Clarkson, P, Abendstern, M, Sutcliffe, C, Hughes, J, Challis, D. (2012) The identification and detection of dementia and its correlates in a social services setting: Impact of a national policy in England Dementia September 2012 vol. 11 no. 5 617-632

Downs M. Embodiment: the implications for living well with dementia. Dementia (London). 2013 May;12(3):368-74. doi: 10.1177/1471301213487465.

Drennan VM, Norrie C, Cole L, Donovan S. Addressing incontinence for people with dementia living at home: a documentary analysis of local English community nursing service continence policies and clinical guidance. J Clin Nurs. 2013 Feb;22(3-4):339-46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365

2702.2012.04125.x. Epub 2012 Jul 13.

Drennan, VM, Cole, L, Iliffe . A taboo within a stigma? a qualitative study of managing incontinence with people with dementia living at home, BMC Geriatrics 2011, 11:75

Drennan, VM, Greenwood, N, Cole, L, Fader, M, Grant, R, Rait, G, Iliffe, S. Conservative interventions for incontinence in people with dementia or cognitive impairment, living at home: a systematic review BMC Geriatrics 2012, 12:77 doi:10.1186/1471-2318-12-77

Ebly EM, Hogan DB, Rockwood K. Living alone with dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999 Nov-Dec;10(6):541-8.

Eggermont L H, Scherder E J. Physical activity and behaviour in dementia: a review of the literature and implications for psychosocial intervention in primary care. Dementia 2006; 5(3): 4 1-428.

Ekelund P, Rundgren A. Urinary incontinence in the elderly with implications for hospital care consumption and social disability. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1987 Apr;6(1):11-8.

Evans D, Lee E. Impact of dementia on marriage: a qualitative systematic review. Dementia (London). 2014 May;13(3):330-49. doi: 10.1177/1471301212473882. Epub 2013 Jan 25.

Flint A, Skelly J. The management of urinary incontinence in dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1994;9:245–6.

Hägglund D. A systematic literature review of incontinence care for persons with dementia: the research evidence. J Clin Nurs. 2010 Feb;19(3-4):303-12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365 2702.2009.02958.x.

Hasegawa J, Kuzuya M, Iguchi A. Urinary incontinence and behavioral symptoms are independent risk factors for recurrent and injurious falls, respectively, among residents in long term care facilities. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010 Jan-Feb;50(1):77-81. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2009.02.001. Epub 2009 Mar 17.

Hellström L, Ekelund P, Milsom I, Skoog I. The influence of dementia on the prevalence of urinary and faecal incontinence in 85-year-old men and women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1994 Jul-Aug;19(1):11-20.

Hirasawa, Y, Masuda, Y, Kuzuya, M, Kimata, T, Iguchi, A, Uemura, K. End-o life experience of demented elderly patients at home: findings from DEATH project. Psychogeriatrics, Volume 6, Issue 2, pages 60–67, June 2006

Hirsh D, Fainstein C, Musher D. Do condom catheter collecting systems cause urinary tract infection? JAMA 1979;242:340.

Idiaquez J, Roman GC. Autonomic dysfunction in neurodegenerative dementias. J Neurol Sci. 2011 Jun 15;305(1-2):22-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.02.033. Epub 2011 Mar 25. Review.

Iltanen-Tähkävuori, S. Design and dementia: A case of garments designed to prevent undressing. Dementia January 2012 vol. 11 no. 1 49-59

Jirovec M. Urine control in patients with chronic degenerative brain disease. In: Altman H ed. Alzheimer’s disease problems: prospects and perspectives. New York: Plenium Press, 1986.

Jirovec MM, Wells TJ. Urinary incontinence in nursing home residents with dementia: the mobility-cognition paradigm. Appl Nurs Res. 1990 Aug;3(3):112-7.

Kraemer HC, Taylor JL, Tinklenberg JR, Yesavage JA.The stages of Alzheimer’s disease: a reappraisal. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1998 Nov-Dec;9(6):299-308.

Kraijo, H, Brouwer, W, de Leeuw, R, Schrijvers, G.Coping with caring: Profiles of caregiving by informal carers living with a loved one who has dementia. Dementia November 7, 2011 1471301211421261

Leung FW, Schnelle JF. Urinary and fecal incontinence in nursing home residents. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008 Sep;37(3):697-707, x. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2008.06.005. Review

Lussier M, Renaud M, Chiva-Razavi S, Bherer L, Dumoulin C. Are stress and mixed urinary incontinence associated with impaired executive control in community-dwelling older women? J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2013;35(5):445-54. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2013.789483. Epub 2013 May 8.

Måvall, L, Malmberg, B. Day care for persons with dementia. An alternative for whom? Dementia February 2007 vol. 6 no. 1 27-43

Mo F, Choi BC, Li FC, Merrick J. Using Health Utility Index (HUI) for measuring the impact on health-related quality of Life (HRQL) among individuals with chronic diseases. ScientificWorldJournal. 2004 Aug 27;4:746-57.

O’Donnell BF, Drachman DA, Barnes HJ, Peterson KE, Swearer JM, Lew RA. Incontinence and troublesome behaviors predict institutionalization in dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1992 Jan-Mar;5(1):45-52.

Orrell M, Hancock GA, Liyanage KC, Woods B, Challis D, Hoe J. The needs of people with dementia in care homes: the perspectives of users, staff and family caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr. 2008 Oct;20(5):941-51. doi: 10.1017/S1041610208007266. Epub 2008 Apr 17.

Ouslander J, Leach G, Staskin D, Abelson S, Blaustein J, Morishita L, Raz S. Prospective evaluation of an assessment strategy for geriatric urinary incontinence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989 Aug;37(8):715-24.

Rabins P, Mace N, Lucas M. The impact of dementia on the family. JAMA 1982;248:333–5.

Rai, J, Parkinson, R. Urinary incontinence in adults/ Surgery Volume 32, Issue 6, p286–291

Resnick, NM: “Urinary incontinence in the elderly.” Medical Grand Rounds 3:281-290, 1984.

Sakakibara R, Uchiyama T, Yamanishi T, Kishi M. Dementia and lower urinary dysfunction: with a reference to anticholinergic use in elderly population. Int J Urol. 2008 Sep;15(9):778-88. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2008.02109.x. Epub 2008 Jul 14.

Skelly J, Flint A. Urinary incontinence associated with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 1995;43:286–94.

Tadros G, Ormerod S, Dobson-Smyth P, Gallon M, Doherty D, Carryer A, Oyebode J, Kingston P. The management of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia in residential homes: does Tai Chi have any role for people with dementia? Dementia (London). 2013 Mar;12(2):268-79. doi: 10.1177/1471301211422769. Epub 2011 Nov 20. Review.

Teri L, Borson S, Kiyak HA, Yamagishi M. Behavioral disturbance, cognitive dysfunction, and functional skill. Prevalence and relationship in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989 Feb;37(2):109-16.

Tilvis RS, Hakala SM, Valvanne J, Erkinjuntti T. Urinary incontinence as a predictor of death and institutionalization in a general aged population. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1995 Nov Dec;21(3):307-15.

Toot S, Hoe J, Ledgerd R, Burnell K, Devine M, Orrell M. Causes of crises and appropriate interventions: the views of people with dementia, carers and healthcare professionals. Aging Ment Health. 2013;17(3):328-35. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.732037. Epub 2012 Nov 16.

Ward R, Campbell S. Mixing methods to explore appearance in dementia care. Dementia (London). 2013 May;12(3):337-47. doi: 10.1177/1471301213477412. Epub 2013 Feb 26.

Yap P, Tan D. (2006) Urinary incontinence in dementia – a practical approach, Aust Fam Physician, 35(4), pp. 237-41.

Yokoi T, Okamura H. Why do dementia patients become unable to lead a daily life with decreasing cognitive function? Dementia (London). 2013 Sep;12(5):551-68. doi: 10.1177/1471301211435193. Epub 2012 Mar 16.

The chapter on art, music and creativity for my new book on living better with dementia

The following are the journal references for my chapter on art, music and creativity for my book “Living better with dementia: champions for enhanced friendly communities”. Please do let me know if you wish to have any further academic papers cited. And also please do let me know if you wish local initiatives or innovations to be featured in my chapter, and I will do my best to include them if appropriate.

Very many thanks.

Amaducci L, Grassi E, Boller F. Maurice Ravel and right-hemisphere musical creativity: influence of disease on his last musical works? Eur J Neurol. 2002 Jan;9(1):75-82.

Basaglia-Pappas S, Laterza M, Borg C, Richard-Mornas A, Favre E, Thomas-Antérion C. Exploration of verbal and non-verbal semantic knowledge and autobiographical memories starting from popular songs in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013 May;25(5):785-95. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212002359. Epub 2013 Feb 7.

Beard, R.L. Art therapies and dementia care: A systematic review 2012 11: 633-656.

Bisiani L, Angus J. Doll therapy: a therapeutic means to meet past attachment needs and diminish behaviours of concern in a person living with dementia–a case study approach. Dementia (London). 2013 Jul;12(4):447-62. doi: 10.1177/1471301211431362. Epub 2012 Feb 15.

Blood AJ, Zatorre RJ. Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 Sep 25;98(20):11818-23.

Budrys V, Skullerud K, Petroska D, Lengveniene J, Kaubrys G. Dementia and art: neuronal intermediate filament inclusion disease and dissolution of artistic creativity. Eur Neurol. 2007;57(3):137-44. Epub 2007 Jan 10.

Camic PM, Chatterjee HJ. Museums and art galleries as partners for public health interventions. Perspect Public Health. 2013 Jan;133(1):66-71. doi: 10.1177/1757913912468523.

Camic PM, Tischler V, Pearman CH. Viewing and making art together: a multi-session art gallery-based intervention for people with dementia and their carers. Aging Ment Health. 2014 Mar;18(2):161-8. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.818101. Epub 2013 Jul 22.

Camic PM, Williams CM, Meeten F. Does a ‘Singing Together Group’ improve the quality of life of people with a dementia and their carers? A pilot evaluation study. Dementia (London). 2013 Mar;12(2):157-76. doi: 10.1177/1471301211422761. Epub 2011 Oct 31.

Chakravarty A. De novo development of artistic creativity in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2011 Oct;14(4):291-4. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.91953.

Crutch SJ, Isaacs R, Rossor MN. Some workmen can blame their tools: artistic change in an individual with Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2001 Jun 30;357(9274):2129-33.

Eekelaar, C., Camic, P. M., Springham, N. Art galleries, episodic memory and verbal fluency in dementia: An exploratory study. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, Vol 6(3), Aug 2012, 262-272.

Fletcher PD, Clark CN, Warren JD. Music, reward and frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2014 Oct;137(Pt 10):e300. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu145. Epub 2014 Jun 11.

Fletcher PD, Downey LE, Witoonpanich P, Warren JD. The brain basis of musicophilia: evidence from frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Front Psychol. 2013 Jun 21;4:347. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00347. eCollection 2013.

Fornazzari LR. Preserved painting creativity in an artist with Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2005 Jun;12(6):419-24.

Gjengedal E, Lykkeslet E, Sørbø JI, Sæther WH. ‘Brightness in dark places': theatre as an arena for communicating life with dementia. Dementia (London). 2014 Sep;13(5):598-612. doi: 10.1177/1471301213480157. Epub 2013 Mar 13.

Gold K. But does it do any good? Measuring the impact of music therapy on people with advanced dementia: (Innovative practice). Dementia (London). 2014 Mar 1;13(2):258-64. doi: 10.1177/1471301213494512. Epub 2013 Jul 26.

Gordon N. Unexpected development of artistic talents. Postgrad Med J. 2005 Dec;81(962):753-5.

Gross SM, Danilova D, Vandehey MA, Diekhoff GM. Creativity and dementia: Does artistic activity affect well-being beyond the art class? Dementia (London). 2013 May 22. [Epub ahead of print]

Guétin S, Portet F, Picot MC, Pommié C, Messaoudi M, Djabelkir L, Olsen AL, Cano MM, Lecourt E, Touchon J. Effect of music therapy on anxiety and depression in patients with Alzheimer’s type dementia: randomised, controlled study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;28(1):36-46. doi: 10.1159/000229024. Epub 2009 Jul 23.

Hafford-Letchfield T. Funny things happen at the Grange: introducing comedy activities in day services to older people with dementia–innovative practice. Dementia (London). 2013 Nov;12(6):840-52. doi: 10.1177/1471301212454357. Epub 2012 Jul 9.

Holland AC, Kensinger EA. Emotion and autobiographical memory. Phys Life Rev. 2010 Mar;7(1):88-131. doi: 10.1016/j.plrev.2010.01.006. Epub 2010 Jan 11. Review.

Hsieh S, Hornberger M, Piguet O, Hodges JR. Neural basis of music knowledge: evidence from the dementias. Brain. 2011 Sep;134(Pt 9):2523-34. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr190. Epub 2011 Aug 21.

James IA, Mackenzie L, Mukaetova-Ladinska E. Doll use in care homes for people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006 Nov;21(11):1093-8.

Janata P. The neural architecture of music-evoked autobiographical memories. Cereb Cortex. 2009 Nov;19(11):2579-94. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp008. Epub 2009 Feb 24.

LaBar KS, Cabeza R. Cognitive neuroscience of emotional memory. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006 Jan;7(1):54-64. Review.

Lazar A, Thompson H, Demiris G. A systematic review of the use of technology for reminiscence therapy. Health Educ Behav. 2014 Oct;41(1 Suppl):51S-61S. doi: 10.1177/1090198114537067.

Mezirow J. (2000) Learning to think like an adult. In J. Mezirow and Associates, Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in process. (pp. 3-33). San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Miller BL, Boone K, Cummings JL, Read SL, Mishkin F. Functional correlates of musical and visual ability in frontotemporal dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000 May;176:458-63.

Miller BL, Cummings J, Mishkin F, Boone K, Prince F, Ponton M, Cotman C. Emergence of artistic talent in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 1998 Oct;51(4):978-82.

Miller, B.L., Yener, G, Akdal, G. (2005) Artistic patterns in dementia, Journal of Neurological Sciences (Turkish), vol. 22(3), pp. 245-249.

Mitchell G, McCormack B, McCance T. Therapeutic use of dolls for people living with dementia: A critical review of the literature. Dementia August 25, 2014 1471301214548522.

Mitchell G, McCormack B, McCance T. Therapeutic use of dolls for people living with dementia: A critical review of the literature. Dementia (London). 2014 Aug 25. pii: 1471301214548522. [Epub ahead of print]

Mitchell G, Templeton M. Ethical considerations of doll therapy for people with dementia. Nurs Ethics. 2014 Sep;21(6):720-30. doi: 10.1177/0969733013518447. Epub 2014 Feb 3.

Omar R, Hailstone JC, Warren JE, Crutch SJ, Warren JD. The cognitive organization of music knowledge: a clinical analysis. Brain. 2010 Apr;133(Pt 4):1200-13. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp345. Epub 2010 Feb 8.

Pezzati R, Molteni V, Bani M, Settanta C, Di Maggio MG, Villa I, Poletti B, Ardito RB. Can Doll therapy preserve or promote attachment in people with cognitive, behavioral, and emotional problems? A pilot study in institutionalized patients with dementia. Front Psychol. 2014 Apr 21;5:342. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00342. eCollection 2014.

Ramachandran, VS, Hirstein, (1999) The science of art: a neurological theory of aesthetic experience. Journal of Consciousness Studies (6), no.6-7, pp.15-51.

Rankin KP, Liu AA, Howard S, Slama H, Hou CE, Shuster K, Miller BL. A case-controlled study of altered visual art production in Alzheimer’s and FTLD. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2007 Mar;20(1):48 61.

Roe B, McCormick S, Lucas T, Gallagher W, Winn A, Elkin S. Coffee, Cake & Culture: Evaluation of an art for health programme for older people in the community. Dementia (London). 2014 Mar 31. [Epub ahead of print]

Salimpoor VN, Benovoy M, Longo G, Cooperstock JR, Zatorre RJ. The rewarding aspects of music listening are related to degree of emotional arousal. PLoS One. 2009 Oct 16;4(10):e7487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007487.

Seeley WW, Matthews BR, Crawford RK, Gorno-Tempini ML, Foti D, Mackenzie IR, Miller BL. Unravelling Boléro: progressive aphasia, transmodal creativity and the right posterior neocortex. Brain. 2008 Jan;131(Pt 1):39-49. Epub 2007 Dec 5.

Stevens, J 2012, ‘Stand up for dementia: performance, improvisation and stand up comedy as therapy for people with dementia; a qualitative study’, Dementia, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 61-73.

Takahata K, Saito F, Muramatsu T, Yamada M, Shirahase J, Tabuchi H, Suhara T, Mimura M, Kato M. Emergence of realism: Enhanced visual artistry and high accuracy of visual numerosity representation after left prefrontal damage. Neuropsychologia. 2014 May;57:38-49. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.02.022. Epub 2014 Mar 11.

Takeda M, Hashimoto R, Kudo T, Okochi M, Tagami S, Morihara T, Sadick G, Tanaka T. Laughter and humor as complementary and alternative medicines for dementia patients. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2010 Jun 18;10:28. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-28.

Tanaka, Y, Nogawa, H, Tanaka, H. (2012) Music Therapy with Ethnic Music for Dementia Patients, International Journal of Gerontology Volume 6, Issue 4, December 2012, Pages 247 257.

Topo, P, Mäki,O, Saarikalle, K, Clarke, N, Begley, E, Cahill, S, Arenlind, J, Holthe, T, Morbey, H, Hayes, K, Gilliard, J. Dementia October 2004 Assessment of a Music-Based Multimedia Program for People with Dementia vol. 3 no. 3 331-350

Woods RT, Bruce E, Edwards RT, Elvish R, Hoare Z, Hounsome B, Keady J, Moniz-Cook ED, Orgeta V, Orrell M, Rees J, Russell IT. REMCARE: reminiscence groups for people with dementia and their family caregivers – effectiveness and cost-effectiveness pragmatic multicenter randomised trial. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(48):v-xv, 1-116. doi: 10.3310/hta16480.

Zeilig H. Gaps and spaces: representations of dementia in contemporary British poetry. Dementia (London). 2014 Mar 1;13(2):160-75. doi: 10.1177/1471301212456276. Epub 2012 Aug 17.

Personalised medicine, genetics and Big Data: the “New Jerusalem” for dementia?

The fact that there are real individuals at the heart of a policy strand summarised as ‘young onset dementia’ is all too easily forgotten, especially by people who prefer to construct “policy by spreadsheet”.

It is relatively uncommon for a dementia to be down to a single gene, but it can happen. And certainly, even if there might not be ‘cure’ for today or tomorrow, identification of precise genetic abnormalities might provide scope for genetic counseling. Markus (2012) argues that many monogenic forms of stroke are untreatable, and therefore, specialised genetic counseling is important before mutation testing. This could be particularly important in asymptomatic individuals, or those with mild disease; for example, potential cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) patients who have migraine but have not yet developed stroke or dementia. Mackenzie and colleagues (Mackenzie et al., 2006) published on a group of families with a clinical diagnosis of tau-negative, ubiquitin-immunoreactive neuronal inclusions (NII). The authors discussed how findings across the literature appeared to suggest that, in this particular condition, NII are a highly sensitive pathological marker for progranulin genetic mutations and their demonstration may be a way of identifying cases and families that should undergo genetic screening.

But is this genomics revolution the beginning of a “New Jerusalem” in dementia, beyond the headlines?

“Big data” refers to information that is too large, varied, or high-speed for traditional methods of storage, processing, and analytics. For example, one application of mining large datasets that has been particularly productive in the research community is the search for genome-wide associations (“Genome-Wide Association Studies (“GWAS”)). GWAS rely on analysis of DNA segments across vast patient populations to search for DNA variants associated with a particular disease. To date, GWAS analyses have identified a handful of promising genetic associations with Alzheimer’s disease, including Apo E4.

This is clearly wonderful if “money does grow on trees”, but the concern for initiatives such as these such work is resource-intensive, and diverts resources from frontline improvements in wellbeing of people living with dementia. Investors also have to be mindful of their financial return compared to the risk of such initiatives. One of the biggest complaints of proponents of “Big Data” is that data tend to be pocketed in a fragmented, piecemeal fashion.

As the McKinsey Centre for Business Technology (2012) state in an interesting document called, “Perspectives on digital business”:

“The US health care sector is dotted by many small companies and individual physicians’ practices. Large hospital chains, national insurers, and drug manufactuers, by contrast, stand to gain substantially through the pooling and more effective analysis of data.”

Vast collections of genomic data obviously represent a goldmine for health providers around the world. Meltzer (2013) reviews correctly that personalized medicine been the subject of increased basic and clinical research interest and funding. Meltzer describes that a knowledge of the genetic and molecular basis of clinical heterogeneity should make it possible to more reliably predict the likely outcomes of alternative approaches to treatment for specific individuals and therefore what course of action is likely to be best for any given patient. Knowledge of personal genetic traits might allow accurate prediction of those invididuals who are most likely to experience adverse events through medication (Markus, 2012).

Both ‘Big Data’ and ‘personalised medicine’, in being couched language of bringing value to operational processes in corporate strategy, tend to lose the precise cost-effectiveness arguments at an accounting level. The new CEO of NHS England, Simon Stevens, will have raised eyebrows with the Guardian piece entitled, “New NHS boss: service must become world leader in personalised medicine” from 4 June 2014 in “The Guardian” newspaper (Campbell, 2014) . Whether the National Health Service of the UK can cope with this, with inevitable transfer of funds from the public funds to private funds, with all the talk of ‘sustainability’, is a different matter. It is difficult to predict what the uptake of personalised medicines will be, even if every patient has access to his or her personal genomic sequence in years to come. All jurisdictions have to consider whether they can justify the sharing of information for public interest overcoming concerns about data privacy and security, and ultimately this is a question of legal proportionality.

The pitch from corporate investors tend to minimise biological practicalities too. For example, it is still yet to be determined what the precise interplay between genetic and environmental factors are, particularly for the young onset dementias. And the assumption that all ‘big’ data are ‘good’ data could be a fallacy. There are 1000 billion neurones in the human brain, and it is well known that not all neuronal connections between them are ‘productive’; in fact a sizeable number are redundant. Heterogeneity in genetic sequences might be meaningful, or utterly spurious, and it could be a costly experiment to wait to find out how, when there are more pressing considerations about both care and cure.

But is this genomics revolution the beginning of a “New Jerusalem” in dementia, beyond the headlines?

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) is the second most common cause of dementia in individuals younger than 65 years (Ratnavilli et al., 2002). It is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characteristically defined by behavioural changes, executive dysfunction and language deficits. The behavioural variant of FTLD is characterised in its earliest stages by a progressive, insidious change in behaviour and personality, considered to reflect underlying problems in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (Rahman et al., 1999). FTLD has a strong genetic background, as supported by positive family history in up to 40% of cases, higher than what reported in other neurodegenerative disorders and by the identification of causative genes related to the disease (Seelaar et al., 2011). The notion that genetic background might affect disease outcomes and rate of survival, modulating the onset and the progression of the pathological process when disease is overt (Premi et al., 2012). Given the consolidated role of genetic loading in FTLD, the likely effect of environment has almost been neglected.

Only recently, it has been reported that modifiable factors, i.e. education and occupation, might act as proxies for reserve capacity in FTLD. Patients with a high level of education and occupation can recruit an alternative neural network to cope better with cognitive functions (e.g. Borroni et al., 2009; Spreng et al., 2011). But the search for treatments for particular types of dementia based on their underlying genes and genetic products is arguably not an unreasonable one. A good example is provided by the Horizon Scanning Centre of the National Institute for Health Research of NHS England in September 2013 (NIHR HSC ID: 8239): leuco-methylthioninium, which is a “tau protein aggregation inhibitor”. It acts by preventing the formation and spread of neurofibrillary tangles, which consist of aberrant tau protein clusters that aggregate within neurons causing toxicity and neuronal cell death in the brain of patients with certain forms of dementia. Leuco-methylthioninium is a stabilised, reduced form of charged methylthioninium chloride. The clinical trials for this are under way. The medication at the time of writing may or may not work safely.

No. This genomics revolution the beginning of a “New Jerusalem” in dementia, especially when social care is on its knees.

References

Borroni B, Premi E, Agosti C, Alberici A, Garibotto V, Bellelli G, Paghera B, Lucchini S, Giubbini R, Perani D, Padovani A. (2009) Revisiting brain reserve hypothesis in frontotemporal dementia: evidence from a brain perfusion study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 28, pp. 130–135

Campbell, D. (2014) New NHS boss: service must become world leader in personalised medicine, The Guardian, 4 June. http://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/jun/04/nhs-boss-world-leader-personalised-medicine.

Mackenzie, I.R., Baker, M., Pickering-Brown, S., Hsiung, G.Y., Lindholm, C., Dwosh, E., Gass, J., Cannon, A., Rademakers, R., Hutton, M., Feldman, H.H. (2006) The neuropathology of frontotemporal lobar degeneration caused by mutations in the progranulin gene, Brain, 129(Pt 11), pp. 3081-90.

Mendez, M. (2006) The accurate diagnosis of early-onset dementia. Int J Psychiatry Med, 36(4), pp. 401– 12.

McKinsey Centre for Business Technology (2012) Perspectives on digital business.

Rahman, S., Sahakian, B.J., Hodges, J.R., Rogers, R.D., Robbins, T.W. (1999) Specific cognitive deficits in mild frontal variant frontotemporal dementia, 122 (Pt 8), pp. 1469-93.

Ratnavalli E, Brayne C, Dawson K, Hodges JR. (2002) The prevalence of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology, 58(11), pp. 1615-1621.

Spreng, R.N., Drzezga, A., Diehl-Schmid, J., Kurz, A., Levine, B., Perneczky, R. (2011) Relationship between occupation attributes and brain metabolism in frontotemporal dementia, Neuropsychologia, 49, pp. 3699–3703.

The Dementia Alliance International is not a convenient marketing tool for dementia salesmen

The following is the draft of an extract from my chapter “Stigma, citizenship and living better with dementia” in “Living better with dementia: how champions can break down the barriers”, by Shibley Rahman with Forewords by Prof Alistair Burns, Kate Swaffer and Chris Roberts.

The really important question therefore is: how can people living with dementia lead? A really important steer for this came from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation in a report by Toby Williamson called “A stronger collective voice for people with dementia” (October 2012). The Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project (DEEP) was a project which aimed to explore, support, promote and celebrate groups and projects led by or actively involving people with dementia across the UK that were influencing services and policies, affecting the lives of people with dementia. DEEP was a one year project which finished in Summer 2012. One of their key recommendations was that national and local organisations providing services or working with people with dementia need to develop and implement involvement plans, allocating resources to develop new groups, link groups together and help them share resources. Furthermore, it was recommended that researchers and research networks need to involve groups of people with dementia in helping to identify research topics, advise on research findings and undertake research on topics identified as important by people with dementia. Thankfully, this work has now been extended as part of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation’s work “Dementia Without Walls”, with various stakeholders also involved.

Ruth Bartlett erself found that keeping a diary has the potential to be used much more widely in patients living with dementia. In her opinion, the main advantage of this method is that unlike interviews, the diarist, rather than the researcher, is ultimately in control of how and when data are collected (e.g. Bartlett, 2011). Bartlett argues that diaries encourage participants to record thoughts and feelings as and when they occur and wherever they feel most comfortable; it therefore has the potential to compensate for short-term memory problems associated with dementia, plus it could help to minimise ‘respondent burden’ traditionally associated with interview based studies involving people with dementia (Cottrell and Schulz, 1993, p. 209). Bartlett has further suggested that people living well with dementia are willing, able to campaign, and presenting this at national and international conferences.

Dementia Alliance International (DAI) is the first global group, of, by and for people with dementia, where membership is comprised exclusively of people with dementia. Dementia Advocacy and Support Network International (DASNI) was the first organisation set up in 2001 by people with dementia; however their membership was not exclusive to people with dementia. There subsequently saw a sprinkling of groups at national levels, the Scottish Dementia Working Group (2002), the European Dementia Working Group (2012) and the Australian Dementia Working Committee (2013) were set up with membership of people with dementia, supported by their national Alzheimer’s organisations.

DAI was therefore established in January 2014 to promote education and awareness about dementia, in order to eradicate stigma and discrimination, and to improve the quality of the lives of people with dementia. DAI advocates for the voice and needs of people with dementia, and provides a global forum, aiming to unite all people with dementia around the world to stand up and speak out.

In the last few years, the voices of people with dementia around the world have become stronger, with leaders including Richard Taylor, Janet Pitts and Kate Swaffer. More recently a number of people with dementia have been discussing things globally, finally giving birth to DAI, to ensure issues such as social isolation, discrimination, stigma and exclusion are addressed. Their members wished to build a group consolidating the vast global networks of people with dementia now speaking and collaborating with each other over the Internet through blogs, Twitter, Pinterest, Facebook and other social media. The modern internet now offers incredible opportunities for organising social movements. too large or too difficult for a single person to undertake. In typical crowdsourcing applications, large numbers of people add to the global value of content, measurements, or solutions by individually making small contributions. Such a system can succeed if it attracts a large enough group of motivated participants,such as Wikipedia, Flickr and YouTube. These successful crowdsourcing systems have a broad enough appeal to attract a large community of contributors, giving true credibility to the idea that the whole is more than the sum of its constituent parts. And initial experience of people living well with dementia and the social media has led to interest in a related activity called ‘friendsourcing’. Friendsourcing attempts to synthesise social information in a social context: it is the “use of motivations and incentives over a user’s social network to collect information or produce a desired outcome, using as a guide what members of the network themselves consider to be important” (Bernstein et al., 2010).

But the notion that dementia is a cognitive or behavioural disability puts the debate into an altogether different stratosphere. Instead of aspirational ‘dementia friendly communities’, a title which itself is open to abuse by politicians, other leaders and charities, the narrative then becomes treating persons with dementia for whom policies cannot serve to their detriment. That is unlawful, under indirect discrimination in various legal jurisdictions. That is therefore an enforceable right. But why is there a feeling that things have not improved much despite various global initiatives.

Batsch and Mittleman (2012) in their ADI World Alzheimer Report, “Overcoming the stigma of dementia” remark that:

“Government and non-government organisations in some countries have?been working tirelessly to pass laws aimed at eliminating discriminatory practices such as making people with dementia eligible for disability schemes. Regional organisations within countries have worked with local governments to improve access to services and delay entry to residential care, most of the time by trying to reduce stigma amongst family carers and health and social service professionals through increased education and regulations.”

Beard and colleagues (2009) offer practical suggestions for how a volte face in thinking could come about:

“Study participants reported various ‘rough spots’ along the path of dementia and their strategies for circumventing them. There were personal, interactional, and environmental factors that caused them difficulties. Strategies included concrete activities, emotional responses, and environmental adaptations. Respondents used cognitive aids, made various modifications, garnered assistance from others, and practiced ‘acceptance’ to deal with persistent problems. Barriers resulted from the disease itself as well as personal obstacles and pressures from others. Participants clearly demonstrated that their lives were meaningful and could be further enriched through advocacy, a positive attitude, and physical, mental, and social engagement. These data show persons with dementia performing the emotional work of illness management, incorporating related contingencies into everyday life, and reframing their own biographies. As they creatively adapted and constructed meaning, order, and selves that were valued, respondents demonstrated agency by actively accommodating dementia into their lives rather than allowing it to be imposed upon them by structural forces.”

The highly intriguing aspect now is that even the narrative of ‘involvement’ is being reframed. This was indeed warned about by Beresford (2002) who suggested service user involvement has emerged out of two different rationales for participation – one consumerist, the other democratic. The former claims that greater efficiency, efficacy and effectiveness will result from appropriately-placed service user feedback mechanisms. The latter, democratic approach, often framed in a rights discourse, views user participation as a form of self advocacy. The history of mental health activism can be dated far further back, to 1620, when inmates at the Bedlam asylum petitioned for their rights (Weinstein, 2010). That the DAI finds itself having attracted the attention of large charities, Big Pharma and social enterprises promoting living well with dementia is not altogether surprising therefore, even despite its relatively young existence.

References

Bartlett, R. (November 2011) Realities Toolkit #18: Using diaries in research with people with dementia.

Batsch, N. L., Mittelman, M. S. (2012) World Alzheimer’s report. Overcoming the stigma of dementia. Executive summary. London, UK: Alzheimer’s Disease International.

Beresford, P. (2002) ‘User Involvement in Research and Evaluation: Liberation or Regulation? Social Policy & Society, vol. 1(2), pp. 95-105.

Cottrell, V., Shulz, R. (1993) The perspective of the patient with Alzheimer’s disease: A neglected dimension of dementia research, The Gerontologist, 33 (2), 205-211.

Weinstein, J. (2010) Mental Health, Service User Involvement and Recovery, London: Jessica Kingsley.

Lots of small gains will see our shared vision for living better with dementia shine through

When I asked Charmaine Hardy (@charbhardy) if she would mind if I could dedicate my next book, ‘Living better with dementia’ to her, I was actually petrified.

Obviously, Charmaine had every right to say ‘no’. You see, I met Charmaine through Beth on Twitter, and I saw the three letters ‘PPA’ in Charmaine’s Twitter profile. Charmaine’s Twitter timeline is simply buzzing with activity. It’s hard not to fall in love with Charmaine’s focused devotion everywhere, nor with how much she adores her family. This passion, despite daily Charmaine working extremely hard, itself generates energy. People are attracted to Charmaine, as she never complains however tough times get. She thinks of ways to go forwards, not backwards, even when she had trouble with her roses recently. She basically creates a lot of good energy for all of us. As Charmaine’s Twitter profile clearly states, “I’m a carer to a husband with PPA dementia.”

Things are not right with the external world though. We have millions of family unpaid caregivers rushing around all the time, trying to do their best. Seeing these relationships in action, as indeed Rachel Niblock and Louise Langham must do at the Dementia Carers’ Call to Action (@DAACarers), must be a fascinating experience. There’s a real sense of shared purpose, often sadly against the “system”.

Contrary to popular opinion, perhaps, I have a strong respect for the hierarchy I find myself in. I have asked Prof Alistair Burns (@ABurns1907), a very senior academic in old age psychiatry, to write one of my Forewords. He also happens to be England’s lead for dementia, but I hope to produce my book as a work of balanced scholarship, which does not tread on any policy toes.

But underlying my book is a highly energised social network (@legalaware), based on my 14000 followers on Twitter. My timeline is curation of knowledge in action, in real time as my #tweep community actively share knowledge on a second-by-second basis. There’s a real change of us breaking down the barriers, and changing things for the better. Sure, some things of course don’t go to plan, but with innovation you’re allowed to crack a few eggs to make an omelette. I have enormous pleasure in that in this network people on the whole feel connected and with this power might produce a big change for the better.

My new book is indeed called ‘Living better with dementia: champions challenging the boundaries‘ – and I feel Kate Swaffer (@KateSwaffer) and Chris Roberts (@mason4233) are doing just that. They continually explain, reasonably and pleasantly, how the system could be much improved from their perspectives of living well with dementia, such that we could end up with a ‘level playing field’. And of course the fact we know what each is up to, for example pub quizzes or plane flights, means that we end up being incredibly proud even if we have the smallest of wins.

My proposed contents of this book are as follows: here.

I am not going to write a single-silo book on living better with dementia, however much the medics would like that.

For many of us in the network, dementia is not a ‘day job’. This shared vision is not about creating havoc. It’s simply that we wish the days of the giving the diagnosis of dementia as ‘It’s bad news. it’s dementia. See you in six months’, as outnumbered. That’s as far as the destruction goes. We want to work with people, many of whom I used to know quite well a decade ago, who felt it was ‘job done’ when you diagnosed successfully one of the dementias from seeing the army of test results. I would like the medics and other professionals not to kill themselves over our urge for change, and work with us who believe in what we’re doing too.

Whenever I chat with Kate and Chris, often with a GPS tracker myself in the form of Facebook chat, I am struck by their strong sense of equity, fairness and justice. And I get this from Charmaine too. The issue for us is not wholly and solely focused on how a particular drug might revolutionise someone’s life with dementia. The call for action is to acknowledge friends and families need full help too, and that people living with dementia wish to get the best out of what they can do (rather than what they cannot do) being content with themselves and their environment. We’re looking at different things, but I feel it’s the right time to explain clearly the compelling message we believe in now.

These values of course take us to an emotional place, but one which leads us to want to do something about it. For me, it’s a big project writing a massive book on the various contemporary policy strands, but one where I’ve had much encouragement from various close friends. For me, the National Health Service kept me alive in a six week coma, taught me how to walk and talk again, when I contracted meningitis in 2007. As I am physically disabled, and as my own Ph.D. was discovering an innovative way of diagnosing a type of frontotemporal dementia at Cambridge in the late 1990s, I have a strong sense of wishing to support people living with dementia; especially since, I suspect, many of my friends living well with dementia will have experienced stigma and discrimination at some time in their lives.

I understand why medics of all ranks will find it easier to deal with what they are used to – the prescription pad – in the context of dementia. But I do also know that many professionals, despite some politicians and some of the public press, are excellent at communicating with people, so will want to improve the quality of lives of people who’ve received a diagnosis. We need to listen and understand their needs, and build a new system – including the service and research – around them. I personally ‘wouldn’t start from here’, but this sadly can be said for much for my life. Every tweet on dementia is a small but important gain for me in the meantime. Each and every one of us have to think, ultimately, what we’ve tried to do successfully with our lives.

Suggested reading

Read anything you can by @HelenBevan, the Chief Transformation Officer for the NHS.

Her work will put this blogpost in the context of NHS ‘change’.

Our new white paper is finally out! “The new era of thinking & practice in change & transformation”. Download at http://t.co/83ZFUO1z99

— Helen Bevan (@helenbevan) July 5, 2014

“Leadership is the art of mobilizing others to want to struggle for shared aspirations.”

“McLaughlin: Leadership has so many definitions that sometimes that term loses its meaning. How do you define it?

Kouzes: Leadership is the art of mobilizing others to want to struggle for shared aspirations. That part about struggling for shared aspirations may set our definition apart.”

I’ve also been though the motions of detailed study of leadership styles in my own MBA.

But this definition of James Kouzes really struck a chord with me.

This is of course not a particularly impressive ‘leadership style’, one sedentary guy with an iPad mini with a large product placement in shot?

I have fleetingly thought too about who is the exact target audience of my book.

While ‘Living well with dementia’ is not a ‘self help book’, it is a fact that many people living well with dementia have warmly received the book.

In fact, in the front row in my line of vision to the left, two people sat, a son and his mother with dementia.

It turns out the son found my talk ‘inspiring’, and thanked me, in front of his mother, for saying which he perceived as powerful: that it’s more important to concentrate on what people can do in the present, rather than they cannot do.

And what did I conclude was the driving intention of an international policy plank about living well with dementia?

I concluded that a positive wellbeing is about a person being content with himself or herself, and his or her own environment.

This is not an issue of being drugged up with a ‘cure for dementia’. It is though saying something equally positive about dementia, if not more positive.

I do not consider the Alzheimer’s Show an “event with a buzz”. For me, it was like a wedding of a best friend. I was thrilled to meet Chris, Jayne, Suzy, Rachel, Louise, Natasha, Joyce, Nigel, Tracey, Tony, and Tommy, some for the first time.

And what you see is what you get with them.

Chris concluded, “Living better with dementia would’ve been a better title.”

And Tommy agreed.

Chris and Tommy live well with dementia.

I agreed too. In a nutshell, ‘living well with dementia’ runs the danger of imposing your moral judgment or ‘standards’ on what living well with dementia is.

For me, living well in alcoholic recovery means not downing a bottle of neat gin when I get up, like I used to do in late 2006/early 2007 when I hit a rock bottom. (The actual rock bottom was when I had a cardiac arrest and epileptic seizure heralding a six week coma in the summer of 2007, rendering me physically disabled.)

But it’s a big thing for me that people who are living well with dementia are actually interested in – and supportive of – my book.

You see, I concede that I don’t live with a dementia yet to my knowledge – though many London cabbies conclude that I do [nicely], when I tell them the title of my book and they see me struggling get into their cab.

Chris pointed out something at first glance very true today – that I didn’t have many friends living with dementia as friends then, when I was writing my book.

Chris is in fact wrong. “Any” not “many”.

Tommy said something curious recently, that it’s ironic that it took an event such as the Alzheimer’s Show in Manchester to bring us all together.

But he’s right. We’re not there for any other reason than to share experiences.

Suzy commented that ‘I get it’. And I do think do, for all sorts of reasons, many of which were quite unintended.

I am currently writing ‘Living better with dementia: champions challenging the boundaries”. It’s going to be a toughie, but I think I can do it.

If only Kate were there too…

I am looking forward to my “Meet the Author” session at Manchester @AlzheimersShow on Saturday

I published a book earlier this year on “Living well with dementia”.

Since then, I have genuinely noticed a change in attitude in people in discussing dementia.

This for me is a major triumph. I wrote the book with a pile of research papers from various professorial laboratories from England and Scotland from the last few years, wondering how I could convey the gist of them in a short book.

Harry Potter it is not. It’s not “Fifty Shades of Grey”.

The book (details here) has been warmly received by people in carer and support networks, persons living well with dementia themselves, nursing students, and by members of the public.

I have no idea whether any medical professionals have read it, or commissioners, but they’d be precisely the group of people who could benefit from reading it as well?

I am genuinely really excited about doing my ‘Meet the author’ session on Saturday.

Friday 4th July 9.30am – 5.00pm

Saturday 5th July 9.30am – 4.30pm

MANCHESTER EventCity.

Venue: EventCity, Phoenix Way, Off Barton Dock Road, Urmston, Manchester, M41 7TB

Please do come and find me if attending! I can be easily direct messaged on my Twitter @legalaware 24/7 if you’re following me.

This is what you can do while there! at The Alzheimer’s Show Manchester:

- DISCOVER dementia and care exhibitors including care at home, care homes, living aids, funding, legal advice, respite care, training, telecare, assistive technology, charity, research, education, finance and entertainment

- MEET Admiral Nurses in free, confidential 1-2-1 clinics

- LISTEN TO high profile speakers covering a range of topics in the Alzheimer’s Matters Theatres

- PUT your questions to the experts in the daily ‘Question Time’ panel sessions

- HEAR personal experiences of caring for a person with dementia, join in the ‘Open Mic’ session and listen to a series of practical advice talks in The Alzheimer’s Talks & Topics Theatre

- MAKE USE of Community Integrated Care’s Quiet Area for carers to leave a person in the care of a qualified dementia specialist

- TAKE PART in the free Practical Workshop, sessions include music, singing, Tai Chi, creating dementia friendly environments and assistive technology

- FIND informative product and service talks in The Exhibitor Workshop

- BECOME a Dementia Friend and learn more about Dementia Friendly Communities

[source language="<a"][/source]

My own PhD at Cambridge under Prof John Hodges was in the cognition of the behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia, so I am especially looking forward to Prof Stuart Pickering-Brown’s talk on the genetics of frontotemporal dementia.

Details of what is happening at the Alzheimer’s Show “Alzheimer’s Matter Theatre” are here.