Home » Posts tagged '6 Cs'

Tag Archives: 6 Cs

‘Whole person care’ needs a bit of tinkering and strong leadership

In a now very famous article, “The genius of a tinkerer: the secret of innovation is combining odds and ends”, Steve Johnson describes how innovation must be allowed to succeed in face of regulatory barriers.

“The premise that innovation prospers when ideas can serendipitously connect and recombine with other ideas may seem logical enough, but the strange fact is that a great deal of the past two centuries of legal and folk wisdom about innovation has pursued the exact opposite argument, building walls between ideas”

“Ironically, those walls have been erected with the explicit aim of encouraging innovation. They go by many names: intellectual property, trade secrets, proprietary technology, top-secret R&D labs. But they share a founding assumption: that in the long run, innovation will increase if you put restrictions on the spread of new ideas, because those restrictions will allow the creators to collect large financial rewards from their inventions. And those rewards will then attract other innovators to follow in their path.”

Bundling of goods can offend competition law, so that’s why legislators in a number of jurisdictions are nervous about ‘integrated care’.

In the past, Microsoft has accused of abusing Windows’ dominant status in the desktop operating system market to give Internet Explorer a major advantage in the browser wars.

Microsoft argued bundling Internet Explorer with Windows was just innovation, and it was no longer meaningful to think of Internet Explorer and Windows as separate things, but European authorities disagreed.

There’s no doubt that ultimately ‘whole person care’ will be some form of “person centred care”, where the healthcare needs (as per medical and psychiatric domains currently) are met.

But it is this idea of treating every person as an individual, with a focus on his or her needs in relation to the rest of the community which is the most challenging aspect of whole person care.

Joining up medical and social care with an ‘unified care record’ has never been attempted nationally, but it makes intuitive sense that care information from one institution should be made available to another.

Far too many investigations are needlessly repeated on successive admissions of the same patient, which is exhausting for the person involved. It would make far more sense to have a bank of results of investigations for persons, say who are frail, who are at risk of repeated admissions to acute hospitals in this country.

And this can’t be brought in with the usual haphazard ‘there is no alternative’ and ‘a pause for consultation’ if things go wrong. The introduction of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) and the CareData makes one nervous that lightning will strike a third time.

Labour has had long enough to think about what could go wrong.

Care professions might feel themselves ill-prepared in person-centred care. A range of training needs, from seasoned physicians to seasoned occupational therapists, will have to get themselves oriented towards the notion of a ‘whole person’. This might involve getting to grips with what a person can do as well as what they can’t do.

The BMA will need to be on board, as well as the Royal Colleges. Doctors, nurses, and all allied health professionals will have to double declutch from the view of people as problem lists, and get themselves into a gear about their patients as individuals who happen to be well or ill at the time.

This needs strong leadership, not people proficient at counting beans such that the combined sum total of a PFI loan interest payments and budget for staff doesn’t send a Trust into deficit.

Nor does it mean hitting a 4 hour target, but missing the point as a Trust does many needless admissions as they haven’t in reality fulfilled their basic admissions assessment fully.

For too long, politicians have been stuck in the groove of ‘efficiency savings’, ‘PFI’, ‘four hour waits’, and become totally disinterested in presenting a person-oriented service which looks after people when they are well as well as when they’re ill.

Once ‘whole person care’ finds its feet, with strong leadership and evident peer-support, we can think about how health is dependent on other parts of society working properly, such as housing and transport.

Technology, if this means that a GP could immediately know what a hospital physician has prescribed in real time in an acute admission, could then be worth every penny.

For the last few years, the discussion has centred around alternative ways of paying for healthcare instead of thinking how best to offer professional care to patients and persons.

The fact that this discussion has been led by non-clinicians is patently obvious to any clinician.

Technology also has the ability to predict, say in thirty years, which of the population is most likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease. Do you really want one of your fellow countrymen to have health insurance premiums at sky high because of having been born with this genetic make-up?

A lot of our problems, like the need for compassion, have been as a result of the 6Cs battling head-on with a 7th C – “cuts”. It’s impossible for our workforce to perform well if they haven’t got the correct tools for the job.

Above all, whole person care needs strong leadership, not just management. And if we get it right the NHS will be less focused on what it’s exporting, but more focused on stuff of real importance.

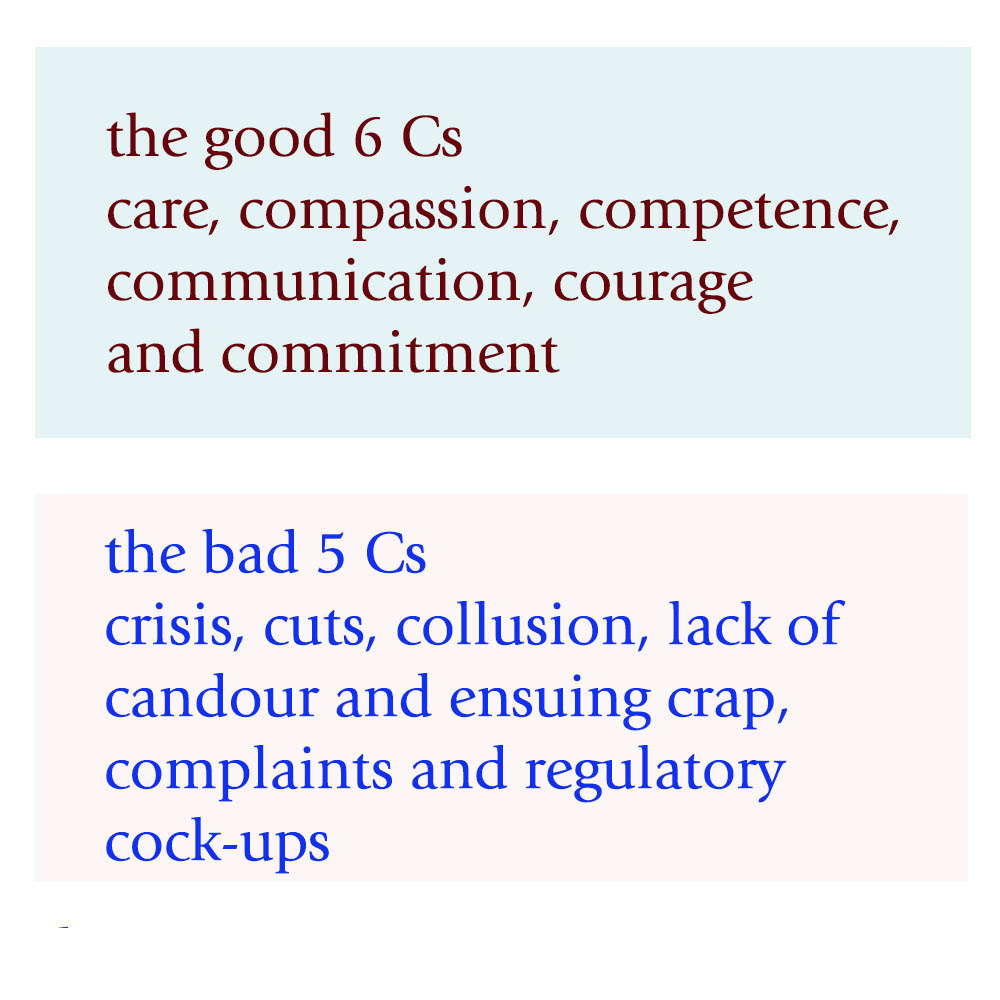

The 11 Cs – can we avoid another Mid Staffs one year after the last Francis Report?

This is the NHS leaflet on the 6Cs here.

Even for the official 6Cs, powerful forces are at play in undermining the acute medical take.

The 6Cs still, though, potentially form the ‘greater good'; that of the ‘ying Cs’.

But it’s how they engage with the 5 other ‘yang Cs’ which will determine whether there’s another Mid Staffs, more than one year on from the last Francis Report.

1. Care

Care is described as a “core business”, perceiving each event with a patient as a transaction which is a potentially billable event.” Caring defines us and our work” indeed is true; as it defines to some extent how people get paid. Unfortunately, the way in which care goes wrong is pretty consistent in the narrative. For example, nurses may be too ‘posh’ to care. In this version, nurses who are too academic are incapable of caring for which there is little published evidence. The other more likely version is that junior nurses are “too rushed to care”. This is understandable, in that if there are ten people still waiting to be clerked in, it can be hard for all professionals to focus on taking a proper history and examination without cutting corners, for examination in completing an accurate neurological examination of the cranial nerves. However, the emergency room often cultivates a feeling of a conveyor belt, with a feeling of “Now serving number 5″. A patient experience is not going to be great if the doctor, nurse or AHP appears rushed in clerking in a patient. The patient feels more like they are in a sheep dip as “continuity of care” between different medical teams suffers.

2. Compassion

“Compassion is how care is given through relationships based on empathy, respect and dignity.” Again there is some irony in the same management consultants outfit recommending compassion by healthcare professionals, when the same professionals have recommended ‘efficiency savings’. Compassion in the NHS can of course be extremely difficult to deliver from the nurses remaining after there have been staff cuts, and the remaining nurses are having to work twice as fast ‘to beat the clock’, or a target such a “four hour target”.

3. Competence

“Competence means all those in caring roles must have the ability to understand an individual’s health and social needs.” This is of course is motherhood and apple pie stuff. The problem comes if the NHS ‘productivity’ is improved with lateral swapping of job rôles: that some functions are downgraded to other staff. Health care assistants might find themselves doing certain tasks which had been reserved for them. If there’s mission creep, the situation results of receptionists triaging a patient, rather a physician’s assistant doing a venflon. Competence of course cannot be delivered by untrained staff delivering an algorithm, as has been alleged for services such as NHS 111.

4. Communication

Communication is central to successful caring relationships and to effective team working. The overall “no decision about me without me” mantra of course has been made a mockery of, with unilateral variation of nursing and medical contracts (with adjustments to terms and conditions, and pay, of staff by NHS managers without any dialogue.) If you don’t communicate any errors in clinical care to the patient (reflected in the ‘lack of candour’ below), the patient and relatives are bound to leave with an unduly glossy version of events of the acute medical assessment. This can of course bias the outcome in the ‘Friends and Family Test’.

5. Courage

“Courage enables us to do the right thing for the people we care for, to speak up when we have concerns.” Take the situation where your Master (senior nurse) is wishing to implement a target, but you’re the one rushed off your feet with missing drug charts, no investigations ordered, no management plan formed as the patient was shunted out of A&E before the 4 hour bell started ringing? Are you therefore going to be able to speak out safely against your Master when your Master is the one who determines your promotion? If you’re made of strong stuff, and completely fastidious about patient safety, you might decide ‘enough is enough’ by whistleblowing. But the evidence is that whistleblowers still ultimately get ‘punished’ in some form or others.

6. Commitment

“A commitment to our patients and populations should be the cornerstone of what we doctors, nurses, and allied healthcare professions do, especially in the “experience of the patients.””. Of course, if you get a situation where junior staff are so demoralised, by media witch hunting, it could be that people are indeed driven out of the NHS for working for other providers, or even other countries. A commitment to the public sector ethos may have little truck if you’ve got more interest in ‘interoperability’, or ‘switching’, which are of course the buzzwords of introducing ‘competition’ into healthcare systems.

There can be some downright ‘yang Cs’ epitomising danger for the acute medical take and hospital.

7. Crisis

When things get out of hand, some of the more hyperbolic allegations might conceivably happen. With people lose the plot, they are capable of anything. And if the system is too lean, and there’s a road traffic accident or other emergency, or there’s an outbreak of rotavirus amongst staff, there may be insufficient slack in the system to cope.

8. Cuts

Whilst patient campaigners have been right to emphasise that it’s more of a case of safe staffing rather than a magical minimum number, there’s clearly a number of trained staff on any shift below which it’s clearly unsafe for the nurses to deliver good nursing care. Cuts in real terms, even if that’s the same budget (just) for an increased numbers in an elderly population, can of course be a great motivator for producing unstable staffing, as the Keogh 14 demonstrated. That might be especially tempting if ‘financially strained’ NHS FTs are trying to balance their budgets in light of PFI loan repayments.

9. Collusion

This can affect a nurse’s ability to communicate problems with courage, if senior nurses are colluding with certain consultants in meeting targets. This means that medical consultants who are recipient of the non-existent drug charts, non-existent management plans, or non-existent investigation orders can probably take one or two weeks to ‘catch up’, but the ‘length of stay’ gets extended. Frontline staff might take the risks. But senior nurses might collude with the management to deliver ‘efficiency savings’ and promote themselves. That’s not fair is it?

10. Lack of Candour and Ensuing Crap

This target-driven culture of the NHS, and excessive marketing of how wonderful things are, must stop. A lack of honest communication with the patient through candour can lead to patients never knowing when things go wrong. This is a cultural issue, and it may be legislated upon at some point in the future. But without this cultural willingness by clinical staff to tell patients when things have unnecessarily got delayed through the missing drug charts etc., they will only get to know of things going badly wrong.

11. Complaints and Regulatory Cock-ups.

If things go badly wrong, they may generate complaints. These complaints may as such not matter if the system completely ignores complaints. For example, there has been only one successful judicial review against the PHSO since 1967. The recent review of the complaints process for NHS England has revealed how faulty the process is. There has been criticism of the clinical regulators in their ability to enforce patient safety too, particularly in light of Mid Staffs.

As you can see, the system is delicately balanced.

If transparency is the best disinfectant, it’s time to reveal the other five Cs for a start?

The most important thing of course may be Culture, the 12th C. If the culture is toxic, as happened in Mid Staffs, it may be hard to analyse the problem in terms of its root causes.