Home » Public Health

Death might not be inevitable in Ed Miliband’s “leader speech”, but taxes might be?

Tobacco use is expected to kill around 5.4 million people worldwide a year.

It is undeniable that the state of the NHS is directly linked to the overall state of the economy. Austerity has posed a challenge to patient safety, though the official line is that “efficiency savings” have not impacted on safety in England. Nonetheless, it is a fact that unsafe levels of staffing have often been at the root of shortfalls in clinical safety.

The “Keogh review” could not have been a clearer example of this.

The public tend to be most concerned about the NHS if there is an identifiable event, such as Mid Staffs, or breaches of the four hour wait.

It is no big secret that Labour intend to make the NHS THE big issue of the general election campaign of 2015. This is despite the Conservatives’ electoral strategy Lynton Crosby not wishing to discuss the NHS.

But like a Marlboro cigarette, the issue of the link between Lynton Crosby, Philip Morris International Inc. (“Philip Morris”) and smoking policy has been a slow burn in the last year or so.

Labour has always wished to paint the picture that the Conservatives do not come with “clean hands” to the discussion of smoking and health.

There has always been the question: are the public aware of the financial problems facing the NHS? And, despite an universal consensus for low taxes, would they wish something to be done in the specific case of the NHS?

A new dawn for NHS campaigners was the relief that the media, who once a upon a time had been respected, were conflating “unsustainable” and “unaffordable” in their discussions of NHS funding. The NHS is, as they will tell you, should be comprehensive, universal, and free at the point of need. It is hard to know precisely where this confusion had arisen from. I remember vividly complaining about this on this SHA blog in October 2013.

In yesterday’s speech, the Shadow Chancellor Ed Balls made the direct link between income from taxes for the Government and the NHS.

“‘Next year, after just five years of David Cameron – with waiting times rising, fewer nurses and a crisis in A&E – we will have to save the NHS from the Tories once again,’ he said. ‘And we will do what it takes.’”.

Also in October 2013, the Local Government Association published a pamphlet entitled, “Changing behaviours in public health – to nudge or to shove?”.

And there is more than a cigarette paper between the two main political parties here on this ssue.

The current government has made exploring the potential of behavioural change a priority. In fact, the coalition agreement itself made direct reference to the issue, stating that the government would be “harnessing the insights from behavioural economics and social psychology”.

But likewise it has also clear that tools available to government include more draconian approaches as shown by the fact that consultations were carried out on plain packaging for cigarettes (a shove) and minimum pricing for alcohol (a smack). However, neither policy has subsequently been introduced.

I, over a year ago, wrote on this blog on the topic of changing behaviour in relation to smoking.

Ed Miliband has been banging on his “cost of living crisis” drum for some time. And, in fairness to him, it is an issue which resonates with the general public. For socialists, such as Owen Jones, the issue does particularly resonate as an example of how privatised companies with vested interests have protected their profits at the expense of their customers. They are able to do this due to markets, which have not failed from the perspective of the shareholder, but which have clearly failed from the perspective of the end user.

And a noteworthy consideration here is that such providers have been able to rely on robust demand, for example the need to drink water or to make a phone call. Likewise, certain luxury brands have not seen their profit margins dented by the global economic recession.

Indeed, on May 12 2009, it was reported that tobacco use would continue, possibly grow, during recession, according to experts at the time.

Death and taxes may be inevitable according to the famous Benjamin Franklin quote. But Lord Stewart Wood, advisor and friend to Ed Miliband, is known also to be petrified that Labour once again becomes known as THE “tax and spend” party. Whilst Labour might have been flirting with sexier and covert ways of working things to their advantage, such as “predistribution”, an epiphany lightbulb moment came when Labour realised it could get away with taxing entities rather than people, provided that it did not offend the neoliberal virtues of competition and enterprise.

In an economic downturn, products seen as giving comfort in the midst of stress tend to sell very well. In the U.S. and abroad, tobacco is no exception. That’s why taxing a commodity which does not become popular, and which could damage your health, is such an attractive political policy.

Just under a year ago, in October 2013, Ben Page as Chief Executive of Ipsos MORI presented a talk: “Public opinion: What price the NHS?”.

79% of the general public were reported as opining that the NHS should be protected from cuts (as opposed to other areas such as policing, benefits or schools).

88% of people agreed that the NHS “would face a severe funding problem in the future”.

Lack of resources and investment in the NHS is way above (42%) is way above other factors which could be posited to be “the biggest threat” to the NHS (including, for example, not enough doctors or nurses, or too much management).

Fast forward to now, and in a September 2014 report from “The Health Foundation”, entitled “More than money: closing the NHS quality gap”, the authors Richard Taunt, Alecia Lockwood and Natalie Berry considered that the NHS faces a significant financial challenge is well known and much discussed. This ‘financial gap’ has been projected to reach £30bn by 2021. This is due to the disparity between the pressures on the NHS and the projected resources available to it.

In the leader’s speech later today, Ed Miliband is ex[ected to put the nation’s health at the centre of a 10-year plan for Britain’s future on Tuesday, front loading the NHS with funding from a novel windfall tax on the profits of UK tobacco companies and the proceeds of a mansion tax on homes worth more than £2m.

A windfall tax normally has its critics because it’s considered to be a very short term measure that risks really damaging the relationship between government and big businesses.

But here is a windfall tax somewhat like no others – as the demand for cigarettes, despite the threat from e-cigarettes, is largely sustainable, and Labour if it is at any war with business is as at war with big businesses abusing markets.

In his final Labour party conference speech before next year’s general election, Miliband will tell sceptical voters he can bring the country back together and offer six ambitious goals, including changes to the NHS, designed to overcome “the greatest challenges of our age and transform the ethics of how Britain is run” over the next decade.

A mansion tax could raise £1.7bn, and had originally been earmarked by the shadow chancellor, Ed Balls, to fund a 10p starting rate of income tax, but that is now due to be funded by abolishing the marriage tax rate.

The poorest twenty per cent of households in Britain spend an average of £1,286 per year on ‘sin taxes’, including betting taxes, vehicle excise duty, air passenger duty, ‘green taxes’ and duty on tobacco, alcohol and motor fuels. In addition, they also spend £1,165 on VAT.

“Sin taxes” have generally been unwelcome by proponents of the free market, such as the Institute of Economic Affairs (“IEA”). In October 2013, the IEA published a report entitled, “Aggressively Regressive: The ‘sin taxes’ that make the poor poorer”.

In this report, the IEA made their disgust for ‘sin taxes’ clear.

It is said that, despite significantly lower rates of alcohol consumption and car ownership, the poorest income group spends twice as much on sin taxes and VAT than the wealthiest income group as a proportion of their income.

It is possible for the Conservative Party to mount an argument that tax is the single biggest source of expenditure for those who live in poverty, and indeed indirect taxes are a major cause of Britain’s cost of living crisis.

The average smoker from the poorest fifth of households spends between 18 and 22 per cent of their disposable income on cigarettes. The tax on these cigarettes consumes 15 to 17 per cent of their income.

And tobacco remains one of the world’s most profitable industries. Current data suggests that smoking is still a huge part of the global consumer landscape and that the habit is not going to die out anytime soon.

Philip Morris is currently the leading international tobacco company, with seven of the world’s top 15 international brands, including Marlboro, the number one cigarette brand worldwide. PMI’s products are sold in more than 180 markets.

In 2013, the company held an estimated 15.7% share of the total international cigarette market outside of the U.S., or 28.3% excluding the People’s Republic of China and the U.S.

On Sep 14th 2014, it was announced that the Board of Directors of Philip Morris on the NYSE/Euronext Paris PM), increased the company’s regular quarterly dividend by 6.4% to an annualized rate of $4.00 per share.

But cigarettes contain more than 4000 chemical compounds and at least 400 toxic substances.

Cardiovascular disease (disease of the heart or blood vessels) is the main cause of death due to smoking.

Smokers are more likely to get cancer than non-smokers. This is particularly true of lung cancer, throat cancer and mouth cancer, which rarely affect non-smokers. The link between smoking and lung cancer is clear. Ninety percent of lung cancer cases are due to smoking. If no-one smoked, lung cancer would be a rare diagnosis – only 0.5 per cent of people who’ve never touched a cigarette develop lung cancer.

Other types of cancer that are more common in smokers are bladder cancer, cancer of the oesophagus, cancer of the kidneys

cancer of the pancreas, and ervical cancer.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a collective term for a group of conditions that block airflow out of the lungs and make breathing more difficult.

So, in a weird way, smoking may come to be saviour of the NHS due to a perversion of market forces. It might be the latest brand of “left populism”, leaving Ed Miliband to want to have another puff. It is hard for the Conservatives to criticise without appearing to come down heavily on the side of tobacco companies such as Philip Morris, but Philip Morris are unlikely to forget this in a hurry if the Labour Party are responsible for denting their profits.

Public health was never a sexy campaigning issue for the Labour Party, despite the best efforts of some, with popular newspapers coming down heavily on the side of the consumer than the “interfering state”. But the whole concept of the ‘responsible state’ has become tarnished with neoliberal governments increasingly outsourcing state functions to companies embroiled in inefficient practices and allegations of fraud practices. A windfall tax on cigarettes, despite giving off an unattractive odour of Labour “going back to its taxing roots”, may be, however, just what the Doctor ordered at this particular time in the history of the service.

And, as all politicians know, you can’t please all of the people all of the time.

After today, Labour might be feeling like (a) whole (person) again.

Would nudging the corporate be more effective than taxing the individual in public health?

It’s hard to pinpoint how the resurgence of liberalism came about so recently.

It could’ve have been a genuine respect for letting people behave as they want free from barriers, in keeping with the neoliberal philosophy of unfettered markets.

The right wing have tended to try to conflate law with bulky ‘red tape’, though it’s interesting reading Hayek’s views on the law straight from the horse’s mouth.

As we approach steadily the UK election to be held on June 7th 2015, the usual criticism from the Conservatives will be that Labour likes to tax and spend your money.

Ed Miliband, with the able support of Livesey and Wood, though wish to have break from this cycle.

Hopefully their attempts will be more successful than Gordon Brown’s aspiration to release himself from ‘boom and bust’.

There is an alternative to taxing foods in individual consumer choices.

A disruptive way of looking at the issue would be to admit, but not necessary accept, that multinational corporates have a huge influence on customer behaviour.

And rather than taxing the individual the different approach is to ‘nudge’ the corporate. In English law, since the seminal case of Salomon v Salomon seen in the House of Lords, the corporate has been viewed as a ‘person’.

Various crimes can be levelled, to varying levels of success, at corporates, including theft, manslaughter and fraud.

It might therefore be possible to ‘nudge the corporate’, rather than taxing individuals.

The idea of a nudge comes from behavioural economics – a field dedicated to understanding why people and institutions make the decisions they do. It grew in the 1960s as scientific knowledge about the brain played a bigger role in psychology but it bubbled over with the publication of ‘Nudge’.

An American economist called Richard Thaler (already a don in behavioural economics) teamed up with Cass Sunstein, a legal scholar, to explain “choice architecture” – and, to defend its use. They argue that by presenting choices better, people make wiser decisions without losing their freedom of choice.

The last Labour administration was viewed by many as excessively authoritarian, e.g. the debacle over detention without trial. Since overplaying its hand, Labour has had moral difficulty in trying to persuade the public for the rôle of state intervention, though it has had some recent theoretical success over fixing colluded energy prices in oligopoly energy markets.

Thaler and Sunstein cite the example of a school cafeteria.

If the healthier food is placed at eye level and is easier to reach than the junk food, individuals’ behaviour might be altered – they might pick the fruit and veg even though they are still free to pick the chips.

‘Big’ has a lot of influence in the UK grocery markets.

Tesco control 30% of the UK grocery market, and have over 2,000 stores in the UK. In 2010 they made a profit of £3.4bn, yet they manage their corporate tax affairs successfully.

‘Fat taxes’ have taken various incarnations over the years, and the statistics cited seem plausible.

For example, a 20% tax on sugary drinks might possibly reduce the number of obese adults in the UK by 180,000.

The impact would be greatest in the under-30s, according to an Oxford and Reading university study.

But some groups say a tax is misguided and simplistic, and would not have an impact on older age groups who might benefit most from losing weight.

Doctors have called for a soft drinks tax to reduce sugar intake. Sugar-sweetened drinks, when taken regularly, have been shown to increase the risk of obesity, diabetes and tooth decay.

In thinking how to influence behaviour, it might be quite sensible to target efforts on the largest retailers here in the UK.

A report published in April 2011 – Right to Retail: Can Localism Save Britain’s Small Retailers? – argues that government must do more to rebalance the retail economy away from the “big four” supermarkets, which control nearly 80% of the country’s £150bn grocery market.

“Britain every year is less and less a nation of shopkeepers – assets and ownership are concentrating, finance has become the preserve of the City of London and high streets have converged as though by centralised design. The UK’s 8,151 supermarket outlets today account for 97% of total grocery sales, and 76% of groceries are sold by just the four biggest retailers,” the report said.

Rather than finding ways of taxing indirectly individual customers, a more sensible way might be way of finding incentives to encourage large corporates to behave a certain way on behalf of the end customer.

Corporates clearly care about tax.

Starbucks is to move its European head office from Amsterdam to London by the end of the year, following a row over corporate tax avoidance. The relocation will concentrate a “modest number of senior executives” in its London operation. The US coffee giant said its leaders would “better oversee the UK market” from the capital, adding that the UK was its largest European market. Last year, Starbucks paid £5m in corporation tax, its first such tax payment since 2009.

But tax is an explosive issue. Tax is seen as regressive and unfair as it lays the greatest burden on the least well off. Discriminatory taxation has thus far been ineffective in producing public health goals. Tax furthermore is unlikely to increase significantly government revenues.

But there are ways of rigging the tax system to encourage certain behaviours. And it might cause a redistribution of resources, judged as ‘fair’, to fulfil a genuine policy goal.

Supermarkets collect meticulous about their transactions anyway. The original criticism of ‘activity based costing’ (1992) cited in the discussion of the original papers of Cooper and Kaplan, which transpose to the criticism of ‘payment by results’, is that the amount of effort to collect data does not justify its subsequent analysis.

But supermarkets will know exactly how many bottles of full-sugar Coca they have sold. These data are easy to collect, in the same way that an individual has to collect meticulously information about his income tax claim.

A single fibre of asbestos can cause an aggressive cancer of the lung lining called mesothelioma. We all know the lengths which have been taken to ‘suppress’ the information about risks of tobacco for lung cancer. We have been witnessing a similar battle over sugar and obesity.

Unlike a single fibre of asbestos causing mesothelioma, knowing how much a certain lifestyle contributes to morbidity can be difficult. But that’s not to say there is no link. While intuitively people have railed against consumption taxes, or ear-marked taxation, the idea of guess-timating the amount of resources to treat people in the NHS from consumer decisions that they have made elsewhere is not totally ridiculous.

For example, greater obesity might lead to a greater prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cirrhosis.

Greater consumption of alcohol might lead to a greater prevalence of cirrhosis.

We already have a scheme which raises money for the NHS from business in the Road Traffic (NHS Charges) Act 1999. Each time there is an accident, a motor insurer is legally obliged to inform the NHS, which will determine if it is liable for any costs. The scheme is administered by the Compensation Recovery Unit. In 2001 the scheme was raising £100 million a year for the NHS.

You may have to pay Capital Gains Tax if you make a profit or gain when you dispose of all or part a business asset. Disposing of an asset might be selling it, giving it away or exchanging it. ‘Entrepreneurial relief’ is available for you as an individual if you are in business, for example as a sole trader or as a partner in a trading business, or hold shares in your personal trading company.

So an adjustment could be made for tax calculations for supermarket chains, and supermarkets will sell a lot of ‘healthy food’ could be given an appropriate tax relief.

But nudges don’t always work – especially when private companies have an interest in making sure consumer behaviour does not change.

Some claim that nudges can infantilise individuals by taking away their moral maturity. Others have also questioned their desirability, stating there is a fine line between persuasion and coercion.

And who’s to know what is healthy today suddenly doesn’t become unhealthy tomorrow. The relief rates for any tax adjustments could only be made according to evidence at any one time, and this evidence can and does change.

But the outcome of the discussion is not important as such. I’m more interested in how you might be able to ‘nudge the corporate’, increasingly with a lot of social and economic power, if there is a widespread unwillingness to tax an individual for his or her own choices.

Corporates might want to prove their sustainability credentials for all I know. But if the general public are still hugely fond of full sugar Coca Cola, corporates might be willing to sell it despite less tax relief. Market forces and all that.

Should you give data altruistically, like you donate blood?

“Alongside what we have already done with the mandatory work programme and our tougher sanctions regime, this marks the end of the something-for-nothing culture,” Duncan Smith said in a conference speech for the Conservative Party last year.

The “something for nothing” meme, reinforced by the concept that “there is no such thing as society” (which Thatcher supporters vigorously claim now was ‘misunderstood’), remains a potent policy narrative.

The anguish which NHS England has experienced may be due to a fundamental problem with trust, as for example demonstrated elsewhere in reaction to GCHQ or NSA. But it could well be due to the “something for nothing” meme coming back to haunt the Government, which narked off public health specialists as the “opt out” has become unhelpfully enmeshed with concerns about commercial profiteering from health data.

“The Blood Donor” is a famous episode from the comedy series “Hancock”, the final BBC series featuring British comedian Tony Hancock. First transmitted on 23 June 1961, Anthony Hancock arrives at his local hospital to give blood. “It was either that or join the Young Conservatives”, he tells the nurse, before getting into an argument with her about whether British blood is superior to other types.

The issue of consent has predictably come to the fore, and it is generally felt that the communications strategy of NHS England over caredata went very badly wrong.

In an almost parallel universe, nothing to do with blood donations, it turns out that Labour is looking at bringing in a US-style system of allowing voters to register on election day amid growing fears that millions of people are about to drop off the official register in a “disaster for democracy”.

In a radical move, Labour is considering allowing same-day registration, which is credited with boosting turn-out from around 59% to 71% in some American states, according to the Demos think-tank. But the point is: mass paperwork involving the population at large is possible.

But now the issue has also become “there is no such thing as altruism”.

The Coalition announced in September 2013 that it had sold Plasma Resources UK to Bain Capital, the private equity firm. Plasma Resources UK (PRUK) turns plasma, the fluid in blood that holds white and red cellsin suspension, into life-saving treatments for immune deficiencies, neurological diseases and haemophilia.

The deal was hugely controversial, beyond typical disagreements over privatisation of national assets, because blood transfusions in the UK are voluntary; if donors think that someone is going to make a profit from their donation, they may well not give blood at all.

Richard M. Titmuss was a professor of social administration at the London School of Economics form 1950 until his death in 1973. He had an international reputation as an uncompromising analyst of contemporary social policy and as an expert on the welfare state.

Richard M. Titmuss’s “The Gift Relationship” (recently edited by Ann Oakley and John Ashton) has long been acknowledged as one of the classic texts on social policy.

A seemingly straightforward comparative study of blood donating in the United States and Britain, the book elegantly raises profound economic, political, and philosophical questions. Titmuss contrasts the British system of reliance on voluntary donors to the American one in which the blood supply is largely in the hands of for-profit enterprises and shows how a nonmarket system based on altruism is more effective than one that treats human blood as another commodity.

His concerns focused especially on issues of social justice. The book was influential and, indeed, resulted in legislation in the United States to regulate the private market in blood.

But shouldn’t you simply donate data ‘for the public good’, in the same way you can choose to donate blood?

The start of a new data sharing scheme involving the pseudonymised medical records of those who do not opt out will be postponed to give patients more time to learn about its benefits and safeguards, NHS England has announced.

Part of the semantics of the legal data involves whether a discussion of the giving of data is ultimately separable from the discussion of the purposes for which these data are ultimately applied.

HSCIC, Health Statistics Collaboration with Insurance Companies, reported on its insurance collaboration intentions last August. Section 2.3.1 of its Information Governance Assessment Addendum stated their intentions very clearly, as Roy Lilley earlier pointed out.

“There is no legal requirement to differentiate between the release of data to NHS commissioners and any other potential data recipient. In the eyes of the law, a government department, a university researcher, a pharmaceutical company, or an insurance company is as entitled to request and receive de-identified data for limited access as a clinical commissioning group, as long as the risk that a person will be re- identified from the data is very low or negligible.”

“Furthermore, all such organisations can make good use of the data. Access to such data can stimulate ground-breaking research, generate employment in the nation’s biotechnology industry, and enable insurance companies to accurately calculate actuarial risk so as to offer fair premiums to its customers.”

The Centre for the Study of Incentives in Health in London is a cluster of academics looking at the pros and cons of whether incentives can influence behaviour.

The issue of paying individuals to change their behaviours in health-enhancing ways, for example by encouraging them to quit smoking or take regular exercise, is a highly topical policy issue, in the UK and internationally. Yet personal financial incentives are potentially riddled with legal ethical issues, with concerns regarding their precise effectiveness, and with further concerns that they may have unintended consequences.

Paying people to undertake particular actions may crowd out their intrinsic motivations for wanting to do those actions, as demonstrated by Richard Titmuss’ classic work on blood donations almost forty years ago

Arguably, a final nail in the coffin came from a report by Randeep Ramesh that drug and insurance companies might be able to, from later this year, buy information on patients – including mental health conditions and diseases such as cancer, as well as smoking and drinking habits – once a single English database of medical data has been created.

However, advocates argued that sharing data will make medical advances easier and ultimately save lives because it will allow researchers to investigate drug side effects or the performance of hospital surgical units by tracking the impact on patients.

Possibly, now is an opportune time to revisit Richard Titmuss’ thesis.

One can only speculate what he would have made of the current furore over ‘caredata’. I suspect though he would care.

The sting in NHS data sharing is in making insurance contracts void

Even Google gave up on their central database for health information called “Google Health“. Whilst few things are as certain as death and taxes, it is fairly certain that there is big money in big data. Lord Shutt of Greetland, Chair of the Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust Ltd. warned, in a foreword on a recent report on “the database state“, that the problem is huge, and as a society we must face up to formidable challenges. There has always been a tough balance in the law between balancing individual rights of privacy and freedom, with the State’s rights of national policy of health and security, for example. Whatever ideological position the Liberal Democrats eventually settle on, it is striking that a Conservative Prime Minister should actually advocate nationalising something.

It is unsurprising that Big Pharma would have welcomed the move. Andrew Witty, the chief executive of GlaxoSmithKline, stated to the Sunday Telegraph he welcomed the data-sharing initiative: “Any action the government takes to improve the environment in this country for life science across these activities is welcome.” The Autumn Statement (2011) had indeed signposted this. It might seem paradoxical that the Department of Health at this time wishes to embark on an initiative to make the NHS “paperless”, at a time when a reorganisation, estimated at £3bn, is currently underway. Patient data, essential for individual patient security, confidentiality and consent, are “rich pickings” for the private healthcare industry, which have not collectively paid to collect this information nor invest in the IT infrastructure of the NHS, but the ethical concerns are enormous. Personalised medicine, dependent on real-time patient information, is “the next big thing” emergency in the pharmaceutical industry, currently keeping stocks of companies very healthy. However, the professional code for Doctors, from the General Medical Council (“GMC”) is very clear on the regulation of patient confidentiality and privacy: this is contained within “Confidentiality” (2009), and clearly guides doctors on the conflicting balance between confidentiality and disclosure.

There are interesting reasons why the operational roll-out of the National Patient Record failed in 2006-7. It is now reported that all prescriptions, diagnoses, operations and test results will be uploaded on to central computers by the end of next year, and, by 2018, all NHS organisations will be expected to be able to share this information with other hospitals, GPs, ambulances and health trusts. Jeremy Hunt hopes local councils will sign up to similar systems, along with private care homes. As with the overall direction of travel of the NHS towards an insurance system where private companies pay “a greater part”, this blurring of the need for patient consent has been insidious.

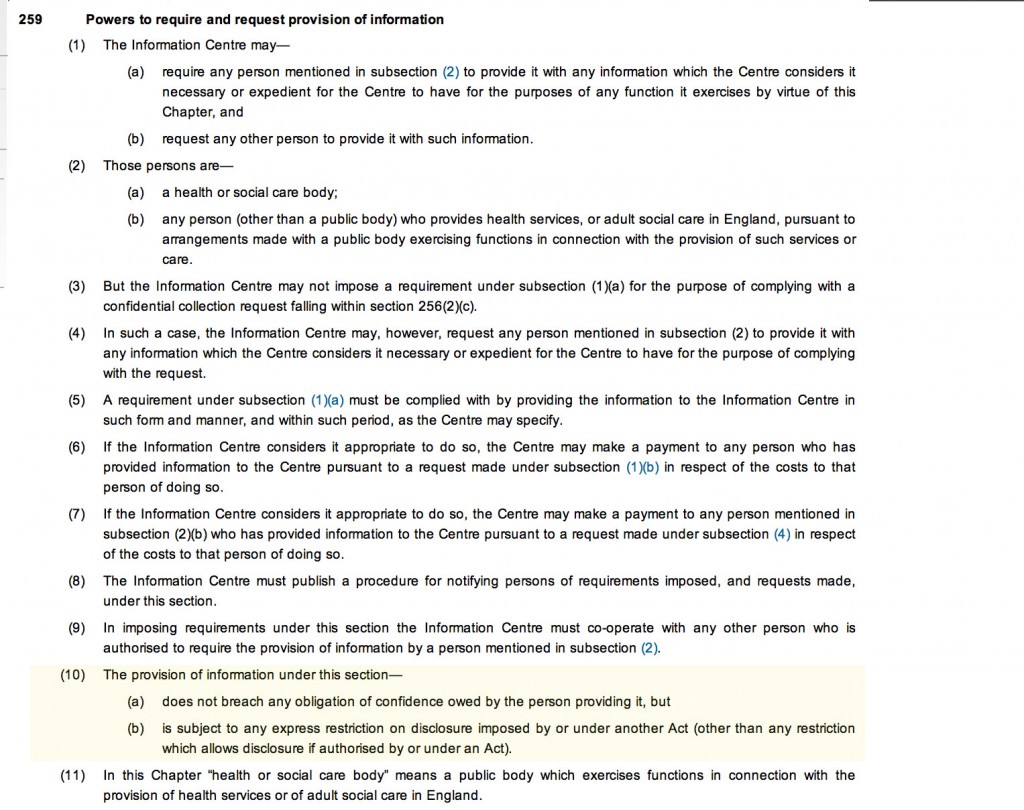

Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006 (originally enacted under Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 2001), allows the common law duty of confidentiality to be set aside in specific circumstances where anonymised information is not sufficient and where patient consent is not practicable. For example a research study may require access to patient identifiable data to allow linkages between different datasets where the cohort is too large for consent. This would require time limited access to identifiable information where gaining consent from a large retrospective cohort would not be feasible and would require more identifiable data than would be necessary for linkage purposes. However, section 10 of the Data Protection Act (1988) currently allows a right for an individual to prevent damage or distress by data processing. This is indeed conveniently “triggered” by section 259(10) of the Health and Social Care Act (2010), i.e. “[the provision] is subject to any express restriction on disclosure imposed by or under another Act (other than any restriction which allows disclosure if authorised by or under an Act”:

The Secondary Uses Service (SUS) Programme supports the NHS and its partners by providing a single source of comprehensive data for planning, commissioning, management, research, audit, public health and “payment-by-results”, a reimbursement mechanism for acute care payments. It is critical to know whether patients maintain a right to opt out of the SUS database. It should not be the case that NHS patients are denied hospital care if they do not agree to my records being sent to SUS. Steve Nowottny in his “Editor’s Blog” for Pulse, a newspaper circulated to GPs, on 8 January 2013 outlined some important very recent developments:

“That year, Pulse ran a ‘Common Sense on IT’ campaign which highlighted a series of concerns over the consent and confidentiality safeguards in the new system.

“GPs wanted patients to have to give explicit rather than merely implied consent before records were created. Plans to use data within the records for research purposes without explicit consent had Catholic and Muslim leaders up in arms, because they feared the research could be purposes contrary to their faiths, such as abortion or stem cell research.

We revealed that celebrities, politicians and other patients whose information is regarded as sensitive would be exempted from the automatic creation of a Summary Care Record, raising questions about the system’s security. And we reported that patients who did not initially choose to opt out of the Summary Care Record would be unable to have their records subsequently deleted.

At the time, it felt as though the stories, while interesting and concerning, were somewhat theoretical. The Summary Care Record’s deployment to date had been patchy and it was far from certain it would continue. In the meantime, fewer than 1% of patients had bothered to opt out. (Now, with nearly 22 million records created and more than 41 million patients contacted, the figure stands at 1.34%).

But the news today that 4,201 patients had Summary Care Records created without them giving even implied consent – and that they will not be able to have them deleted – reignites the whole debate. Suddenly ‘what if’ scenarios have become reality.”

Tim Kelsey is the NCB’s National Director for Patients and Information – his stated aims are to put transparency and public participation at the centre of a transformation of customer service in the NHS. In a recent lecture, he quoted George Soros who said “our social institutions are imperfect, they should be open to improvement [and that] requires transparency and data“. On-line banking and e-ticketing demonstrate the power of open access to personal data in a safe, secure way – for some reason, heath data is deemed more personal that finance and travel arrangements. Data.gov.uk is an example of his vision for the future – the UK has so much medical data, not only about patients but also genomics and other bioinformatics disciplines. The law currently gives the NCB power to mandate more data flows – Kelsey apparently targets April 2014 to get outcomes-based data flows from primary and secondary care – once achieved, next step is to embrace social and specialist care. So, once the data is “freely available”, it can be made available for public participation – he is investing in a course called ‘Code for Health’, a 3 day course to learn how to develop apps. Data are essential from April 2013, there will be push for on-line interaction with GPs, to realise nationally the benefits seen in pilot areas.

So why should commissioners need access to “personal identifiable data”? It is considered that these may be “good reasons”:

- integrated care and monitoring services including outcomes and experience requires linkages across sources

- commissioning the right services for the right people requires the validation that patients belong to CCGs and have received the correct treatments

- aspects of service planning and monitoring on geographic data basis require postcodes for certain type of analysis

- understanding population and monitoring inequalities

- target support for patients and population groups at highest risk requires data from several sources linked together

- specialist commissioning is commissioned outside local areas and can require wider discussions about individual patients and their associated costs

- ensuring appropriate clinical service delivery and process requires access to records

To enable commissioning, ‘personal identifiable data’ including NHS no, DOB, Postcode data needs to flow to “data management integration centres” (“DMICs”). The DMICs need to have similar powers and controls to the Health and Social Care Act information centres to process data It was known that, in order for processing of PID at DMICs to be undertaken legally, a change in legislation would have been required.

David Cameron has stated explicitly his intention for social care to head towards a private insurance system. As stated in the transcript of the interview with Andrew Marr,

“Well the point that was being made earlier on the sofa by Nick Watt, this is a massive problem – that you know more and more people suffering from dementia and other conditions where they go into long-term care and there are catastrophic costs that lead them to have to sell their homes to pay for that care – it’s right to try and put in place a cap which will then open up an enormous insurance market, so people can insure against that sort of catastrophic loss.”

A longrunning conundrum about where there is such intense interest in ‘raising awareness of dementia’. The idea of having GPs and physicians ‘diagnose’ dementia on the basis of a screening test, without it being called ‘screening’ in name, has not been backed up with the appropriate resource allocation for dementia care elsewhere in the system, including adequate training for junior doctors and nurses crucially involved in actual dementia care. Is this and integration of care an entirely virtuous sociological problem? Integration of care at first sight seems to involve primarily avoidance of reduplication of operations, and better ‘coordinated’ care between health and social care and funding. This is not an unworthy ambition at all. It is well known that the endpoint of the Pirie and Butler “Health of Nations” blueprint for NHS privatisation has a greater rôle for the private insurance market as the endpoint, so it makes complete sense to have a fully integrated IT system which private insurers and the Big Pharma can tap into.

Lawyers will, of course, be cognisant about the added beauty of integration of clinical and financial information. One of the biggest banes of insurance markets is information asymmetry, making calculation of risk and potential payouts difficult. Insurers will argue that calculation of risk is only possible with precise information, clinical commissioning groups are merely “statutory insurance schemes”. It is a long-held belief that private insurers refuse to pay off given the slightest lack of compliance in terms and conditions, but private insurers provide that this mechanism needs to exist to protect them making unnecessary payouts. Failure to disclose medical conditions is an excellent way for private insurers to get out of “paying up”, otherwise known as rescission. Of course, this could be taking the “conspiracy theory” far too far, and these concerns about the use of “big data” otherwise than for a “public good” may be totally unfounded.

You can, nonetheless, mount an argument why the current Government wish to progress with this particular approach to private medical data. The private insurance market and Big Pharma stand to benefit massively, and their lobbying is much more sophisticated than lobbying from GPs, physicians or members of the public. The drive towards all nurses having #ipad3s and all TTOs from Foundation Doctors being sent by broadband to nursing homes may seem utterly virtuous, but there are more significant drivers to this agenda beyond reasonable doubt. On the other hand, it’s simply that healthcare policy is in fact improving for the benefit of patients.

Extremely grateful to the work of Prof Ross Anderson, Chair of Computer Security at Cambridge University, and Phil Booth @EinsteinsAttic on Twitter with whom I have had many rewarding and insightful Twitter conversations with @helliewm.

Are we actually promoting the NHS ‘choice and control’ with the current caredata arrangements?

In the latest ‘Political Party’ podcast by Matt Forde, an audience member suggests to Stella Creasy MP that wearing a burkha is oppressive and should not be condoned in progressive politics. Stella argued the case that she can see little more progressive than allowing a person to wear what he or she wants.

The motives for why people might wish to ‘opt out’ are varied, but dominant amongst them is a general rejection of commercial companies profiteering about medical data without strict consent. This is not a flippant argument, and even Prof Brian Jarman has indicated to me that he prefers a ‘opt in’ system:

Patients are not fully informed about how their information will be used. For such confidential data they should have to opt in @legalaware

— BrianJarman (@Jarmann) January 28, 2014

If people are properly told the pros and cons they can decide if they want to accept the cons, for the sake of the pros @sib313 @legalaware

— BrianJarman (@Jarmann) January 27, 2014

There are potential benefits, but also risks and if the risks happen they’re irreversible. Hence it’s safer to have opt-in. @legalaware

— BrianJarman (@Jarmann) January 27, 2014

Opting out can be argued as not being overtly political, though – it is protecting your medical confidentiality. People may (also) have political reasons for doing this, but the choice is fundamentally one about your right to a private family life. The government (SoS) has accepted this, and that is why it is your NHS Constitution-al right to opt out – you don’t have to justify it and if you instruct your GP to do it for you, she must.

It’s argued fairly reliably that section 251 of the NHS Act 2006 maps exactly onto Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 2001. Section 60 was implemented the following year under Statutory Instrument 2002/1438 The Health Service (Control of Patient Information) Regulations 2002. It is argued that the Health and Social Care Act 2012 did not modify or repeal those provisions of the HSC Act 2001 or the NHS Act 2006, nor did it modify or repeal any related provision of the Data Protection Act 1998. SI 2002/1438 remains in force. However, noteworthy incidents did occur under this prior legislation, see for example this:

Whatever motive you have for arguing against care.data, whether the whole principle of it, the HSCA removing any requirement for consent, the fact that it is identifiable data being uploaded from GP records (i.e. not anonymised or pseudonymised), or that the data will be made available, under section 251, for both research and non-research purposes, to organisations outside of the NHS, etc, the matter remains that the is no control over your data unless you opt-out.

Proponents of the ‘opt out’ therefore propose their two lines of action: either prevent your identifiable data being uploaded (9Nu0) and so effect a block on the release of linked anonymised or pseudonymised (potentially identifiable) data, which otherwise you cannot prevent or control; or block all section 251 releases (9Nu4), whether or not you apply the 9Nu0 code.

The point is, they argue, that you – the patient – cannot pick and choose, when, to whom, or for what purposes your data will be released. You cannot prohibit your data from being released for purposes other than research, or to organisations out with the NHS. This is completely at odds to the ‘choice and control’ agenda so massively advanced in the rest of the NHS. While it has been argued that the arguments against commercial exploitation of these data should have been made clearer beforehand, it’s possibly a case ‘I know we’re going there, but I wouldn’t start from here.’

Compelling arguments have been presented for the collection of population data. It’s argued wee need population data to do prevention and to monitor equity of access and use. It’s an open secret that the current Government is continuing along the track of privatising the NHS; arguably making it all the more important to have good data so we know what is happening. Having more of this data at all starting in the private sector, under this line of argument, is much less transparent, as it’s hidden from freedom of information from the start.

It’s, however, been argued that “the route to data access” has in fact changed. Under Health and Social Care Act (2012), it was intended that either the Secretary of State (SoS) or NHS England (NHSE) could direct HSCIC to make a new database, and – if directed by SoS or NHSE – HSCIC can require GPs (or other care service providers) to upload the data they hold. care.data represents the single largest grab of GP-held patient data in the history of the NHS; the creation of a centralised repository of patient data that has until now (except in specific circumstances, for specific purposes) been under the data controllership of the people with the most direct and continuous trusted relationship with patients. Their GP.

HSCIC is an Executive Non Departmental Public Body (ENDPB) set up under HSCA 2012 in April 2013. NHS England, the re-named NHS Commissioning Board, was established on 1 October 2012 as an executive non-departmental public body under HSCA 2012. Therefore, to suggest that the government has ‘little control’ over these arm’s-length bodies is being somewhat flimsy in argument – they were both established and mandated to implement government strategy and re-structure the NHS. There are also problems with the “greater good” argument; being paternalistic, the opposition to caredata spread bears similarity to the successful opposition to ID cards. This argument presumes that patients will benefit individually, when – and it ignores the fact that it is neither necessary or proportionate –and may be unlawful under HRA/ECHR – to take a person’s most sensitive and private information without (a) asking their permission first, and (b) telling them what it will be used for, and by who. Nobody is above the law, critically.

The fact is that the data gathered may increment the data available to research but that in its current form, care.data may actually not be that useful – it includes no historical data, for starters. And all this of course ignores the fact that care.data (and the CES that is derived from linking it to HES, etc.) will be used for things other than research, by people and companies other than researchers. That is the linchpin of the criticism. Finally, the Care Bill 2013-14 – just about to leave Committee in the Commons – will amend Section 251, moving responsibility for confidentiality from a Minister (tweets by Ben Goldacre here and here).

Anyway, the implementation of this has been completely chaotic, as I described briefly here on this Socialist Health Association blog. What now happens is anyone’s guess.

The author should like to thank Prof Ross Anderson, Chair of Security Engineering at the Computer Laboratory of the University of Cambridge, Phil Booth and Dr Neil Bhatia for help with this article.

Sledgehammers and nuts: opt-outs and data sharing concerns for the NHS?

You couldn’t make it up.

“a substantial number of GPs are so uneasy about NHS England’s plans to share patient data that they intend to opt their own records out of the care.data scheme.”

“The survey of nearly 400 GP respondents conducted this week found the profession split over whether to support the care.data scheme, with 41% saying they intend to opt-out, 43% saying they would not opt-out and 16% undecided.”

Simon Enright, Director of Communications for NHS England, tweeted to indicate methodological issues with concluding too much from this ‘snapshot survey':

@legalaware disappointing that Pulse did self-selecting sample with potential question bias in survey.

— simonenright (@simonenright) January 26, 2014

And of course Simon Enright is right. But one has to wonder how much GPs themselves have been informed about the debate about data sharing concerns. GPs are trained to explore, and in fact examined on exploring, the ‘beliefs, concerns and expectations’ of their patients; so it would be unbelievable to assume that no one had had this particular conversation with a patient.

GPs tend to be a very knowledgeable and versatile group of medical professionals, and indeed many have an active interest in public health.

But here there’s been another problem at play? All of the patients who I know, because of the known issues in waiting for an appointment to see their GP for ‘routine matters’, have decided to opt-out by simply dropping in to sign a form with the receptionist. But that sample could even be more unreliable than the Pulse survey.

For all of the huge budget that’s set aside for NHS England’s interminable activities on patient engagement in the social media and beyond, you’d have thought a spend on explaining data sharing would’ve been money well spent?

Views on an individual’s right to ‘opt out’, described in a previous blogpost of mine, vary.

There are many good arguments for proposing the sharing of care data, but the lack of willingness of industry, primary care or public health to discuss openly how data sharing might be necessary and proportionate, under the legal doctrine of proportionality, is utterly bewildering.

What has resulted is an almighty mess.

In as much as there is a ‘root cause’ of this problem, an unwillingness to make the arguments for data sharing with the general public is a good candidate.

Julie Hotchkiss, a public health physician, has for example written to Tim Kelsey about the matter today.

Dear Mr Kelsey

re:Care.data

I think there is so much to be gained by collation of personal health data – for epidemiological observation (prevalence, time trends, variation), allowing data-linkage enjoyed by other countries such as Sweden, to aid commissioning of health services as well as, of course, for direct patient care. For all these reasons I support in principle the care.data initiative. However I have grave concerns about how the data might be used. I am aware that many, many people share these concerns, and many of these have been expressed in the press in recent weeks. Many of my colleagues (long term NHS employees) are saying they will opt out. There are a number of senior voices in the Public Health world who are urging people to opt out.

NHS England is in a unique place to be able to address these concerns – but in many ways the horse has bolted, and I fear we may never get it back in the stable. PLEASE now put your energies and resources into a full and frank consultation, including IT experts, medical colleges, academia and for goodness sake – the general public! The fact that no such awareness raising and consultation has taken place makes people suspicious. They already don’t blindly trust the NHS / government anymore. So if you want to get health professionals and academics behind you in order to have a greater number of voices advocating for care.data please address the following concerns – in a published document- as soon as possible.

- definitive ownership of the data

- responsibility for data quality

- assurance (ideally in legislation) that ownership or data management will remain with a governmental agency and not be out-sourced

- will the HSC IC own the data, and allow access through a form of brokerage (allowing specific views/queries) or access to the full data set)?

- detailed Information Governance arrangements, e.g. requirements for Section 251 approval?

- what Research Governance / Ethical approval arrangements are being put in place?

- what will organisations have to pay,? and if so is this a handling fee or will they get ownership of the data?

- criteria for granting access to data and legally binding restrictions on usage of the data

- exactly to what extent will records be identifiable (for instance the long-established practice at ONS of suppressing cells with fewer than 5 individuals from disclosure)

Although I expect a response, more than this I expect published documents to detail all these issues. I’m sure there are many other details specialists in health research, Information Governance, medico-legal matters and civil libertarians would require in order to be assured that this was something in which they could participate.

Kind regards

Julie Hotchkiss, Fellow of the Faculty of Public Health

Another question for Tim Kelsey may be, potentially, whether the data from care.data will be processed according to the National Statistics Code of Practice.

It is somewhat unclear why the public health community have not had themselves a discussion with the general public, despite some advocates of this community now complaining very loudly about the presentation of ideas leading to the ‘opt out campaign’.

But they will need to confront the stench of public mistrust aimed at various politicians. Examples of events leading to this profound distrust include the NSA/Snowden affair, and relevations at GCHQ.

The corporate capture in some areas of public health is not a topic which public health physicians have wished to talk about. However, these authors somehow managed to sneak an excellent discussion of the phenomenon here in the British Medical Journal.

There have been calls for much tighter regulation of “data brokers”, as corporates wish to rent-seek this plethora of data. What always appeared to have been lacking was an “intelligent debate” with the general public about data sharing. Nonetheless, the social media, for example “Open democracy: our NHS” websites, have for a very long time been publishing relevant articles on this subject.

There was also the small issue of how the £3bn implementation of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) came into being, which led to a turbo-boost of the outsourcing and privatisation of the NHS. Members of the academic public health community were slow on the uptake there too – some would say “completely asleep on the job”, perhaps not as far as their own research interests are concerned, but on the specific issue of potential violation of valid consent for individuals.

And guess what the Health and Social Care Act (2012) also contains a legal ‘booby trap’, which many did not see fit merited discussion with the general public.

Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006 (originally enacted under Section 60 of the Health and Social Care Act 2001), allows the common law duty of confidentiality to be set aside in specific circumstances where anonymised information is not sufficient and where patient consent is not practicable. For example a research study may require access to patient identifiable data to allow linkages between different datasets where the cohort is too large for consent.

This would require time limited access to identifiable information where gaining consent from a large retrospective cohort would not be feasible and would require more identifiable data than would be necessary for linkage purposes. However, section 10 of the Data Protection Act (1988) currently allows a right for an individual to prevent damage or distress by data processing.

This is indeed conveniently “triggered” by section 259(10) of the Health and Social Care Act (2010), i.e. “[the provision] is subject to any express restriction on disclosure imposed by or under another Act (other than any restriction which allows disclosure if authorised by or under an Act”:

The trust is further eroded through the loss of data from government agencies, coherently tabulated on this Wikipedia page.

Proponents of democratic socialism have long argued that citizens often are not able to buy influence through competing with large corporates, but can legitimately exert influence through the ballot box.

There is also no doubt that people are talking at cross-purposes. There is a bona fide case for disease registries and surveillance, for example. However, the problems of an individual’s data being shared with lack of informed valid consent in the name of population presumed consent do need to be addressed ethically at least.

Public health physicians who would like to see the law applied to promote public health and research overall cannot condone profiteering from personal data abuses. Tim Kelsey has always been adamant that the English law is strong enough to cope with such threats. The scenario has mooted before of private insurance companies being able to abort insurance contracts (rescission) from data disclosed to them, on the grounds of misrepresentation or non-disclosure, but the position of the NHS England has always been to present such scenarios as far-fetched.

However, the issues appear to have been intelligently debated at European level. The draft “EU General Data Protection Regulation on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data” (the EU Regulation), was published in 25 January 2012, and has been debated in the European Parliament for most of the time since then.

Under “Albrecht’s proposals“, health data should generally only be able to be processed for the purposes of historical, statistical or scientific research where individuals have consented to such processing. It would be legitimate for processing in the context of research to take place without consent only where: (a) the research would serve an “exceptionally high public interest”; (b) the research involves anonymous data from which individuals could not be re-identified; and (c) the regulators have given their prior approval. Consent, however, is to follow the stricter interpretation, requiring explicit, freely given, specific and informed consent obtained through a statement or “clear affirmative action”. There is, however, legitimate concerns that these proposals might damage the interests of both corporate and public health communities.

It looks very much like chaos has set in since 2010 in running the NHS. Any party can do better than this.

This is of course an almighty mess, and it is hard to know how the whole thing could have been approached better. A plethora of issues have converged seemingly at once, and there is a possibility a ‘big opt out’ would still deliver a result without the matters having been properly discussed. If you think this is bad, consider what would happen in a national discussion of the terms of our membership of the European Union?

by @legalaware

Cameron’s #NHS of #Cons13 is not a ‘land of opportunity’. That is entirely the problem.

Thankfully the “Big Society”, as such, seems to be dead, having been replaced successfully by the “Pig Society”, with the NHS set to turn into a lucrative promised land of ‘wealth creation’ of asset stripping. Many onlookers, who haven’t been following the trials and tribulations of the NHS narrative in recent months, will not have been familiar with the well worn Jeremy Hunt narrative of the NHS presented yesterday. Jeremy Hunt, it seems, is caught in a time warp where he must present Mid Staffs of the past at all times as a ‘death camp’ where present-day inpatients can only be ill at their peril. However, on this last day of this consultation, this toxifies the story in a way parallel to way traders can misuse market-sensitive information to distort the market. At the beginning of last month, for example, the Nursing and Midwifery Council announced that it would establish an ‘unequivocal professional duty’ for registered nurses and midwifes to raise concerns about patient safety, publicly endorsed by former Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust whistleblower Helene Donnelly.

The stale nasty narrative was all too familiar, with ‘Brian Jarman as the eminent expert’ being wheeled out as a familiar pantomime dame in the pantomime of boos and hisses on the NHS. The “pot of gold” at the end of the rainbow for Jeremy Hunt is not just that ‘the Conservative Party is THE party of the NHS’, which Hunt latterly seems to have become so obsessed about that he is prepared to call ‘hardworking’ NHS staff “coasters”. And yet voters largely are sick of Hunt using the NHS as a political football in this way, and not convinced about his exhausting protestations that the NHS is not being ‘privatised’. For the NHS not to satisfy a conventional definition of privatisation used by all economists, the Conservative Party has uniquely have had to adopt a definition of ‘privatised services’ as services where you’re not charged for anything. For everybody else, privatisation is transfer of state services to the private sector, ideologically in fact ‘benefits for the wealthy’ as you’re in effect providing subsidies for private shareholders from the money from ‘hardworking’ tax payers. It’s the well known trick of ‘money for nothing’ so often complained about by Osborne. It’s what Iain Duncan-Smith called yesterday a ‘hand-out not a hand-up’.

For all the fist pumps about patient safety, it is a plain fact that the £2.4 bn reorganisation of the NHS was primarily about installing an insolvency regime for the NHS, and for providing the machinery for outsourcing as many contracts as possible to the private sector. Cameron’s NHS is nothing to do with ‘stronger communities’ either. For all the heat about ‘listening to patients’, the light has been an enduring legacy of not listening patients even having given them a voice. Once denounced as ‘conspiracy theories’, the situation regarding where the procurement contracts have gone to are now a hard-nosed practicality. The ultimate problem is that ‘the free market’ is not an economic construct. There are very few ‘free markets’ in the world apart from, say, Somalia, as it happens that there has to be regulation to avoid monopolies and oligopolies (markets with few players) abusing the market to hog all the customers, and deliver unconscionable profits for their shareholders. It is either the case that the NHS has not been privatised, or suddenly Serco, Care UK, Circle and Virgin Health have become nationalised.

Without regulation, it is impossible for the market to work properly for the benefit of customers. For the NHS, this is necessary when ‘providers’ offer ‘services’ to ‘users’, and so a third prerequisite of the Health and Social Act in addition to the second one of outsourcing services was to provide the regulatory machine to oversee it. The ‘equality of opportunity’ is an ideological dogma where everyone can profit, where Cameron hopes ‘profit is not a dirty word’. However, in oligopolistic markets, such as utilities, bills get out of control as there is no real competition or choice for effectively the same product, so that the market acts as a “cash cow” for directors and shareholders involved in them. Cameron simply doesn’t ‘get it’ about why or how competition isn’t working in the NHS, so it is critical that the Health and Social Care Act (2012), including its competition thrust, is repealed in the first Queen’s Speech of a Labour 2015 government. It is simply an ideological dogma, but actually a remarkably dangerous one. For allowing a ‘free market’, with ‘light touch regulation’, the few players, like all other privatised industries such as telecoms or energy, can hog all the contracts, make all the money, so profit does indeed become a ‘dirty word’. To run a state-run comprehensive NHS is a worthy ideological goal of itself, in contrast. Parliament can wish to legislate for the NHS to be the ‘preferred provider’ to ensure this, and that is indeed one of the first legislative intentions of a Labour 2015 government. If you don’t run a truly comprehensive NHS, where there is a glut of providers cherrypicking the ten billion hernia operations for low cost and high volume, you won’t be able to treat properly your patient with the rare disease, lending a lie to the notion of Cameron’s Britain where ‘nobody is written off’. By awarding virtually all the contracts to the private sector, and some noteworthy ‘big contracts’, it does seem that the NHS provider is not quite in a “land of opportunity” given its relative lack of experience in making skilled commercial pitches.

In all other babies of Thatcher, the privatised energy or telecoms industries, there has been much foreplay about how ‘we must low barriers to entry’ and yet this does not seem to have altered the reality of all the contracts going to the usual suspects in all sectors, whether it’s health, probation, telecoms and media, or whatever. The actual experience of the ‘free market’ means that the Tories have become the party of big business or corporates, as evidenced by their hardworking delegates in Manchester this week. Ideologically, the Labour Party is not against profit or competition per se, but it appears to be against immoral profits from a rigged market with little or no competition. In that rigged market, it’s incredibly difficult for new entrants to get in somehow into the market. There is no land of opportunity. To that extent, profit is indeed ‘elitist’ for the successful oligopolies of this corporatised world. That is the fundamental difference.

Real economists don’t deny that there can be ‘economies of scale’ from running large organisations. The Conservatives have turned the debate into ‘we don’t want it to be public good, private bad’, but the real issue now is to what extent the NHS can deliver a comprehensive service with so many fragmented bits pulling in incoherent directions. That there is no duty of the State to provide a comprehensive service from the date of the enactment of Cameron’s NHS is highly significant. Instead, the furious ideological self-gratification has gone into running a surplus for the country at large. Last year, the NHS was successful in running a surplus of billions in its budget sheet, and yet successfully managed to avoid re-investing this surplus back into frontline care where the money could have been of considerable benefit to trusts such as “the 14 Keogh Trusts”.

Real economists also need to reclaim the debate. The NHS should not have become, fundamentally, about economics but it has done. It is no longer tenable to say ‘keep politics out of the NHS’. Thousands of nurses cumulatively in parts of the country have been made redundant, with some NHS FT CEOs running unsafe staffing levels. Why should union representation become two ‘dirty words’ in Cameron’s dictionary? The answer is most probably that hard-working hedgies hate hard-working unionised workforces, as it makes share acquisitions very much harder. A unionised workforce should not be ‘public enemy no 1‘ where careworkers have enforceable legal rights, instead of being shoved on zero hour contracts for the benefit of their employer. It’s one thing for a party to advocate ‘tax cuts’ in encouraging enterprise, but it is an altogether different thing if you have a NHS health provider with a registered office in a foreign jurisdiction for the purposes of tax avoidance.

When you peel away of the layers of the Cameron onion on his view of the world, you cannot help but be in floods of tears. David Cameron will attempt to give the ‘sunny uplands’ speech of his life today in Manchester, but the only opportunity in David Cameron’s NHS is the “opportunity cost” of where £2.4 bn could have been better spent. According to Wikipedia, “in microeconomic theory, the opportunity cost of a choice is the value of the best alternative forgone, in a situation in which a choice needs to be made between several mutually exclusive alternatives given limited resources. Assuming the best choice is made, it is the “cost” incurred by not enjoying the benefit that would be had by taking the second best choice available.”

Instead of paying external management consultants on their never-ending gravy-train of the great ‘national hospital sell off’, the money would have been better spent on more frontline staff. Indeed, it’s been a bonanza for those management consultants in a golden age of ‘wealth creation’ at the NHS’ expense. The reality is for these new private health providers is that for all the bogus terminology of ‘transparency’ the data on their staffing levels remains hidden because of the Freedom of Information Act. You can hardly argue that a nurse being laid off to improve the surplus of a NHS hospital or to improve the profit of a private provider, to improve its shareholder dividend for hard-working shareholders, is living in a ‘land of opportunity’.

But it’s all semi-skilled hype from wordsmiths who don’t understand what it is like to work in some areas of society, who are paid to write crap so that a party with an average nearing 70 (according to Jeremy Paxman last night on Newsnight) can clap. At the heart of it is a man who fails to take responsibility for his failed policy for the NHS, but who will definitely be booted out at the beginning of May 2015.

Should e-cigarettes be available on the NHS?

Addicts are great customers, they have a huge appetite for your product and they keep coming back.

Addicts are great customers, they have a huge appetite for your product and they keep coming back.

That of course is the market-driven view of public health. A coherent national public health policy should consider the evidential impact of measures on the health of its citizens.

The last few years have indeed seen a public health which appears to have been somewhat determined by the phenomenon of ‘corporate capture’, such as the interests of corporates rather than public health physicians. This is of course partly a reflection of the current government in office, and spans across a growing number of policies including obesity, packaging of cigarettes, and pricing of alcohol.

A buzzword in management circles has been ‘disruption‘. It is felt that early digital cameras suffered from low picture quality and resolution and long shutter lag. Quality and resolution are no longer major issues and shutter lag is much less than it used to be. The convenience and low cost of small memory cards and portable hard drives that hold hundreds or thousands of pictures, as well as the lack of the need to develop these pictures, also contributed to the successful adoption of these disruptive technologies. Digital cameras have a high power consumption (but several lightweight battery packs can provide enough power for thousands of pictures).

According to Wikipedia, a disruptive innovation “is an innovation that helps create a new market and value network, and eventually goes on to disrupt an existing market and value network, displacing an earlier technology”. It is a term used to describe changes that improve a product or service in ways that the market does not expect.

Disruptive technologies have created new industries and new markets. They have also rendered others obsolete and outdated. They provided consumers with something they did not know they wanted. The economist Joseph Schumpeter referred to this process as “creative destruction.” Early investors in these companies certainly took on a lot of risk. There was no way to know whether or not an idea would be profitable. After all, these ideas had no track record.

The American investment banking firm Goldman Sachs earlier this year released a list of eight disruptive themes that have the potential to reshape their categories and command greater investor attention in the near future. Electronic cigarettes were listed as one of these eight markets investors should keep an eye on, for their potential to transform the tobacco industry.

As described in “E Cigarette Forum”,

The little vaping companies that make alternative devices may not make it into the fortune 500 or onto the boards of the NYSE, but they will survive because they have a passionate clientele. They’re like the little mammals that scurried around the massive feet of the dinosaurs at the end of the Jurassic, 65 million years ago, just as the big guys were about to go belly up. Bet on the little guys. They’ll survive.

On October 8th 2013, the European Parliament is to vote on a proposal to regulate the devices as if they were medical products. E-cigarettes (“e-cigs”), which allow users to inhale nicotine-laced vapour instead of tar-clogged smoke, are a growing market, set to top $1bn in the next three years. Smoking is falling in most rich countries, but “vaping” is rising. In Europe, 7m people are thought to be using e-cigs, which vaporise a solution containing nicotine without the toxins from burning tobacco. Sales of e-cigs in America may treble this year, according to figures from Bonnie Herzog of Wells Fargo, a bank. She thinks their consumption could overtake that of ordinary cigarettes in a decade.

An “e-cig” is composed of a mouthpiece, a liquid nicotine cartridge, a heating element and a battery. When the user inhales on the e-cig, the heating element is activated. The liquid nicotine cartridge is heated and creates a vapor. This is what the user inhales. It is odourless. It doesn’t contain any of the other chemicals or tar found in traditional cigarettes.

E-cigs may be far safer than normal cigarettes and at least as good at getting people to quit smoking as nicotine patches and gum, but they too are based on that addictive substance. Manufactured by hundreds of suppliers using materials from China and elsewhere, the quality and labelling of e-cigs on sale are known to be uneven.

E-cigs can be smoked indoors. Once again, there are no noted effects of secondhand vapour. The vapour that is exhaled has little to no odour. Bar and club owners may even be becoming fans of e-cigs. Users who buy them are more likely to stay in the bar and consume more drinks than they otherwise would. This may add to the ‘coolness’ and convenience factor of these disruptive new products. There are a number of possible suggested benefits.

There is a noted reduction in side effects commonly reported by smokers. Some of these side effects are shortness of breath, dry mouth and headaches. Along with reduction of side effects, there is no secondhand smoke. The vapour that the user exhales quickly vanishes and does not appear to cause harm to bystanders.

A ‘quick reference guide’ for ‘smoking cessation services’, from NICE, published in February 2008 gives an overview of what was perceived then could or should be offered on the NHS to help people give up smoking. This evidence-based guidance presents the recommendations made in ‘Smoking cessation services in primary care, pharmacies, local authorities and workplaces, particularly for manual working groups, pregnant women and hard to reach communities’. It provides a rationale for who could provide smoking cessation services (as it predates the £3bn top-down reorganisation, it refers to a critical rôle for PCTs and SHAs), what pharmacotherapies might be prescribed and for whom (and where they should not be prescribed), which patient groups might be beneficially targeted, and how effectively educational and training resources might be allocated.

It is no secret that despite public health efforts the popularity of electronic cigarettes has increased at a rapid pace in recent years. E-cig sales have doubled in the last two years and they are estimated to reach $1billion in retail sales in 2013. According to a Gallup poll, 74% of smokers want to quit, and Goldman Sachs analysts believe the electronic cigarette is “the most credible alternative to conventional cigarettes in the market today”.

This investment giant estimates electronic cigarettes could reach $10 billion in sales over the next few years and account for over 10% of the total tobacco industry volume and 15% of the total profit pool by 2020. In April 2012, one of the big cigarette companies threw its hat in the ring. This was Lorillard, maker of Newport and other cigarette brands. They spent $135 million on the purchase of blu e-cigs. They’ve seen a lot of success with the brand. Sales have grown from $8 million in in the second quarter of 2012 to $57 million in the second quarter 2013. This is a gain of more than 600%. Lorillard claims they hold around 40% of the total e-cig market share. So of course Big Tobacco is eager to get in on the act, and as Hargreaves notes, cigarette manufacturers Lorillard, Reynolds American, Imperial Tobacco, British American Tobacco, and Altria are all bringing out e-cigs, along with newer companies like Vapor and privately-held NJOY.

There are, of course, risks to this growth. One realistic threat is the tightening of the manufacturing and product standards, or bring in a specific set of rules rather like those governing cosmetics. However, any government would have to be motivated to do this, and, following evidence for ‘corporate capture’ in English policy since the election of the UK Coalition government in 2010, e-cigs are likely to experience an ‘easy ride’.

But there are other considerations. Electric smokes compete with cigarettes yet do not in most places face the same restrictions, to say nothing of excise taxes. They compete with smoking-cessation products yet do not usually have to secure prior approval for products or make them to pharmaceutical standards. If they are required to do either, their price will rise, variety will fall and the uptake by consumers, who are overwhelmingly smokers, will be cut.

Furthermore, the World Health Organisation does not encourage them. America’s Food and Drug Administration is expected to propose restrictions in October. In 2009 it claimed that e-cigarettes were unapproved medical products, but a court said they should be regulated as tobacco products instead. Health authorities worldwide are struggling to deal with this new way of getting a nicotine kick. E-cigarettes are sold as leisure products and as such are covered by safety and quality standards wherever these exist and are implemented. But leaving them, like shoes or beds, to such “catch-all rules” makes some regulators uneasy. The most obvious is the involvement of the FDA. E-cig companies are anticipating that the FDA will get more heavily involved in regulating the e-cig market. This is a known risk currently being priced into e-cig dividends.