Home » Posts tagged 'wilful neglect'

Tag Archives: wilful neglect

What precisely is Jeremy Hunt legislating for in ‘wilful neglect’ which would have prevented a Mid Staffs?

The Leveson Inquiry had to work out why the culture of journalism had gone so badly wrong in places, even with enforceable criminal law, such as the interception of communications or tresspass against the person.

Hunt will be keen to provide enforceable ‘end points’ of the Francis Inquiry. But again, there is an issue here of what went so badly wrong in culture, where there were theoretically enforceable aspects from regulators such as the GMC or NMC.

There has been an intense debate about how many people may have died as a result of poor care over the 50 months between January 2005 and March 2009 at Stafford hospital, a small district general hospital in Staffordshire.

Clearly Hunt feels that there was a ‘culture of cruelty’ in the NHS, as he said yesterday (report in Hansard):

The report published on 6 February 2013 of the public inquiry chaired by Robert Francis QC was the fifth official report into the scandal since 2009, and Francis’s second into the hospital’s failings.

According to s.1(1A) Medical Act 1983, referring to a body corporate known as the “General Medical Council” (GMC)

The main objective of the General Council in exercising their functions is to protect, promote and maintain the health and safety of the public.

The difficulties that the GMC has had in successfully prosecuting Doctors over ‘the Mid Staffs scandal’ are comprehensively discussed elsewhere, and are therefore not the focus of this article.

Similar dead-ends have been experienced by the NMC (for example here), and are not the focus of this article either.

It was reported recently that Doctors and nurses found guilty of “wilful neglect” of patients could face jail as new legislation from the Government.

Wilful neglect will be made a criminal offence in England and Wales under NHS changes as a response to the Mid Staffordshire and other care scandals. The offence is modelled on one punishable by up to five years in prison under the Mental Capacity Act. So how does Jeremy Hunt envisage what this law will do?

Jeremy Paxman presented his interview with Jeremy Hunt, the Secretary of State for Health, last night on “Newsnight”. Paxman asked Hunt directly to give an example. At first, he spoke around the subject, talking about the need for criminal sanctions “for the most extreme cases”.

Hunt finally provided this answer:

Well I think an example might be someone who was responsible for caring for a dementia patient who didn’t give them [sic] food when they needed it and when they knew they needed food. That’s the kind of them I’m thinking about. It’s for people who deliberately neglect people. It’s a very small minority of people and they should feel the full force of the law.

The phrase “when they knew they needed food” is highly significant.

At no point did Hunt specify this was an older patient with dementia.

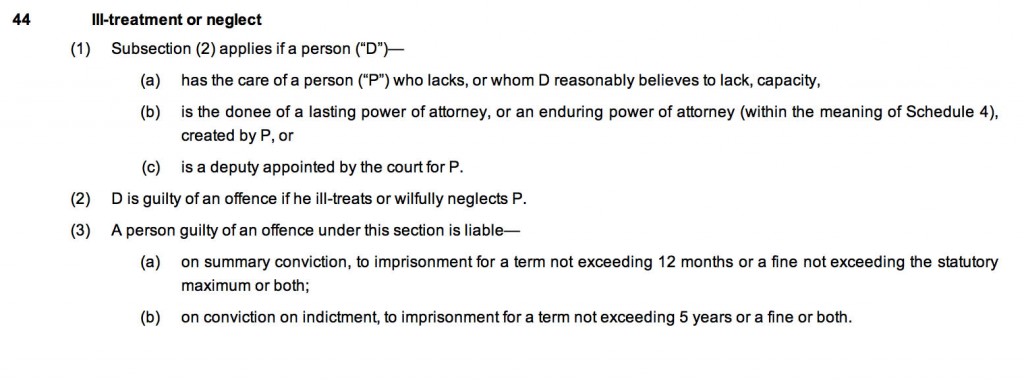

Since 1 April 2007, vulnerable people have been afforded an increased protection by the Mental Capacity Act 2005. The Mental Capacity Act (2005) created the criminal offences of ill-treatment or wilful neglect under Section 44 based on existing principles. This offence could be distinguished from the one contained in section 127 of the Mental Health Act 1983 which creates an offence in relation to staff employed in hospitals or mental nursing homes where there is ill-treatment or wilful neglect.

The offences can be committed by anyone responsible for that person’s care.

As can be clearly seen, the elements of this offence are that the offender:

- has the care of the person in question OR is the donee of a power of attorney OR is a court-appointed deputy;

- reasonably believes the person lacks capacity (or they do lack capacity);

- ill-treats or wilfully neglects the person.

- It can be expected that ill-treatment will require more than trivial ill-treatment, and will cover both deliberate acts of ill-treatment and also those acts reckless as to whether there is ill-treatment.

Wilful neglect can only apply to those who have a duty of care towards people who lack capacity.

Helpfully, part 14.3 of this Code of Practice (Code) accompanying the Mental capacity Provision gives examples of the kind of act that may constitute abuse and ill treatment. Specifically that Code includes “neglect” and “acts of omission”. This, it states, may include ignoring the person’s medical or physical care needs, failing to get healthcare or social care and withholding medication, food or heating. This appears to be alluded to in Jeremy Hunt’s example of a patient with dementia being denied a need – food.

Wilful neglect was supposed to represent a serious departure from the required standards of treatment and usually requires that a person has deliberately failed to carry out an act that they were aware they were under a duty to perform. Neglect or acts of omission could, therefore, include not responding to a person’s basic needs, i.e. assisting with feeding, drinking, toileting or in meeting personal care needs, preventing someone else from responding to those needs, or withholding or preventing access to medical care or treatment.

Back to Jeremy Hunt’s example, the caregiver knew the person with dementia needed food.

This responsibility is important when considering the meaning of the term “wilful” in this context which can be interpreted in two different ways:

- The person understood their responsibilities under the Mental Capacity Act and wilfully disregarded them;

- The person had a duty of care toward the service user and wilfully chose not to learn about it.

This may be reflected in previous cases such as R v Sheppard [1981] AC394 HL (which may be comparable; see discussion).

In consequence, defences could be raised to the effect that the elements of the offence set out in Section 44 are not made out in the following terms:

- there is no section 44 relationship (no care/power of attorney/court-appointed role);

- the person does not lack capacity and/or there was no reasonable belief in such a lack of capacity;

- there was no ill-treatment or wilful neglect.

It is well known that Hunt has been extensive discussions with patient campaigners for Mid Staffs.

But the problem is posed by the choice of Hunt’s example as a patient with dementia. The legitimate question has to be asked that, with the large number of ‘needless deaths’ repeatedly published in media reports, why reports of successful prosecutions under this provision of parliament might have been comparatively few?

From the timeline of the reported cases of neglect, and when this provision was in force, it would appear that this provision was ‘good law’ at the time. Many of the ‘needless deaths’ are widely reported in the media to have involved individuals who lacked capacity.

Why did the “wilful neglect” provision fail to do its stuff over Mid Staffs or Winterbourne, for example? How has Hunt tweaked it so that the law is actually effective for the public good?

It’s worth looking therefore carefully at the current operation of the section 44 provision.

There is no definition of “ill treats” or “neglects” within the Act so every day meanings of the word provide definition. The definition of ill treatment relies upon the definitions of the types of abuse which include physical, emotional, sexual, discrimination, psychological and financial.

Interestingly, neither section 44 of the MCA or section 127 of the MHA provides general protection for older people. Under these provisions they must either lack mental capacity or have a mental illness. In a case where an older person with capacity and no history of mental illness was found to be abused, the abuser would face the standard criminal charges of assault and battery (offences against the person in common law and in statute), and in a very extreme case where the sufferer dies, manslaughter.

So far most cases have involved the prosecution of direct frontline carers, where the evidence is very specific of wrongdoing by an individual. Owners and managers of small care homes have also been successfully prosecuted where there is clear evidence of what might be described as “institutional abuse”. Despite some attempts such charges have not been successfully prosecuted against large scale providers or their senior management, and this is still a longlasting concern of the implementation of the law. There is clear room for such NHS managers, care home managers and their private companies to be prosecuted particularly where they have failed properly to manage the delivery of such policies.

In a criminal context, the change must be proved beyond reasonable doubt, However, it is quite possible that guilt might be determined by magistrates or jurors who are likely to be very unsympathetic to care providers and staff.

One may be justifiably concerned, from the jurisprudence perspective, that the current lack of prosecution is based on a lack of appetite or understanding of care sector standards by prosecutors. A change in this attitude could see many more prosecutions. But again this is another ‘required’ change of culture?

Another problem is that the lawyers and regulators may not understand precisely the nature of what they are regulating against. The argument can be dismissed along the same lines as NHS managers do not ‘need’ to have any knowledge of medicine or nursing.

A prosecution of ‘wilful neglect’ Hunt admitted was so that the defendants could ‘feel the full force of the law’.

This document is typical of one of the many professional concerns of an appetite of being seen to punish hard retributively certain actions. The law must be necessary and proportionate, and one can see in principle how this provision could fulfil a worthy aim of parliament regarding patient safety.

Oncologists frequently perceive the discussion about whether or not to use or continue artificial feeding and/or hydration to be difficult. Successful approaches are not customarily demonstrated during medical training. Food and water are widely held symbols of caring, so withholding of artificial nutrition and hydration may be easily misperceived as neglect by the patient, family, or other professional and volunteer caregivers.

The response to the new ‘wilful neglect’ offence from clinical professionals and patients has been noticeably underwhelming.

There is furthermore a worrying aspect that people within the NHS system will be even more deterred from ‘whistle blowing’ under the Public Interest Disclosure Act [1998] than they were before, for fear of retribution over criminal sanctions.

For the offence of ‘wilful neglect’, the example that Jeremy Hunt gave last night has remarkable similarity to the sorts of offences you might have expected from Mid Staffs or Winterbourne View. The question therefore should be legitimately posed what it is that Hunt himself thinks is to be covered by the new law which was not covered previously. In summary, Jeremy Hunt needs to ask himself what his new law will achieve where section 44 of the Mental Capacity Act had failed.