Home » Posts tagged 'social enterprises'

Tag Archives: social enterprises

Social enterprises and the NHS: who benefits and what’s at stake?

As social enterprises for care get promoted in England, such that they literally get ‘bigger and bigger’, now’s a sensible time to task who exactly benefits and what’s at stake.

Like personal budgets or PFI, a discussion with the public is unlikely to be forthcoming in the near future. Nonetheless, it’s possible to make some inroads into this complicated narrative. At the beginning of this parliament, the Department of Health declared its vision that the NHS should be the “largest social enterprise sector in the world” through the liberation of foundation trusts, and handing over services to NHS staff. Enhancing the role of social enterprises and mutuals in public service provision was right at the heart of the Coalition Government’s vision of the “Big Society”, and part of the aspiration to move one in six public sector jobs into staff-owned companies.

In a somewhat provocatively titled article in the Health Services Journal, “Norman Lamb: Mid Staffs would never have happened at a mutual”, Health minister Norman Lamb suggests that acute trusts could improve staff engagement by becoming social enterprises and argued that the culture problems seen at Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust would never happen in a mutually-owned company. It is not any surprise to anyone who has worked as a clinician in the last decade in the NHS that understaffed services, perhaps cut back as a result of ‘efficiency savings’ to help address ‘the funding gap’, have been the major threat to patient safety in NHS hospitals and Foundation Trusts.

The Berwick Report discusses safe staffing ratios, and staff engagement is a pervasive theme in the whole analysis. And yet curiously the document “The Care Bill explained: Including a response to consultation and pre-legislative scrutiny on the Draft Care and Support Bill“, which indeed calls Mid Staffs a “watershed moment in care”, does not mention social enterprises or mutuals once.

The famous Norman Lamb/Chris Ham review is due to report imminently.

Meanwhile, the Cabinet Office ‘Mutuals Information Service” has a feeling about it of “Well done on setting up your first mutual!”

“Setting up a mutual is a major achievement… However, the transition from the public sector can bring significant challenges… The biggest challenge that comes with leaving the public sector, though, is having to operate as a business. In the first year, you will be focussed on delivering your service and making your mutual work. However, as you build your experience and look to the future, you should start to think about opportunities for expansion and growth.”

All organisations involved in care have have had a tension between board members acting as representatives for particular membership groups and ‘experts’ charged with driving the performance of the organisation forward.

Social enterprises are non-profit ventures designed to achieve both social and commercial objectives. Although trading for a social purpose is hardly a new phenomenon (Hall, 1987), the growth of social enterprise has been a key feature of economic activity in both developed and developing countries.They are hybrid organisations that have mixed characteristics of philanthropic and commercial organisations (Dees, 1998).

According to Alter (2006), social enterprises are driven by two forces:

“first, the nature of the desired social change often benefits from an innovative, entrepreneurial, or enterprise-based solution. Second, the sustainability of the organisation and its services requires diversification of its funding stream, often including the creation of earned income opportunities (p. 205).”

It’s already known the accountability and transparency (corporate governance) mechanisms of social enterprises aren’t always necessarily “fluffy”: see for example this interesting discussion of “asset locks”. Co-operatives have long held to have three groups of participants, according to Johnston Birchall and Richard Simmons (2004). They are: those “true believers” who can be persuaded to train as potential board members, those who can be formed into a kind of club who believe in the aims of the organisation and will participate through voting, attending annual meetings and social events, and supporting campaigns such as fair trade, and a third group which is quite ambivalent.

Birchall and Simmons review that the best way to encourage active participation amongst membership is to reinforce the values of mutuality, engage widely with the community, and to make accountability central to corporate governance and strategy. And “non-uniform engagement” is a well-documented issue with NHS Foundation Trusts (FTs) too. Nonetheless, managers in FTs have described using members of public to give their governance a sense of legitimacy (Allen et al., 2012):

‘They are seen as a very important strategic weapon . . . the governors and their influence into the community, is really, really key’

Multinational corporations have an interest in working with the community too. The construct of ‘corporate social responsibility is important for such corporations to gain ‘competitive advantage” through “value creation” (Husted and Allen, 2007). The European Commission identifies corporate social responsibility as: “a concept whereby companies integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis” (Commission of the European Communities 2001).

Recent examples of the failure of private providers to deliver NHS services, such as Serco with its contract for older people’s services in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough CCG, have led to a greater desire within the NHS to see commissioning in terms of how a provider can deliver a long-term business model with greater social value, going beyond the cost-effectiveness of their work. That’s where social enterprises come in so handy for multi-national companies, and vice versa. And as you progress down the ‘You too can set up a mutual’ aspirational route, you as a member find yourself less interested in real persons and real patients, but get more bogged down with the “bottom line”. Though the field is young, it’s clear private equity want a slice of the action: the “Socially Responsible Investment” is an investment process that integrates social, environmental, and ethical considerations into investment decision-making (Crifo and Forget, 2013).

From a somewhat corporate perspective, Antony Bugg-Levine, Bruce Kogut, and Nalin Kulatilaka gave a neat description of the “social impact bond” in the Harvard Business Review in 2012:

“Another innovation, the social impact bond, deserves special notice for its ability to help governments fund infrastructure and services, especially as public budgets are cut and municipal bond markets are stressed. Launched in the UK in 2010, this type of bond is sold to private investors who are paid a return only if the public project succeeds—if, say, a rehabilitation program lowers the rate of recidivism among newly released prisoners. It allows private investors to do what they do best: take calculated risks in pursuit of profits. The government, for its part, pays fixed return to investors for verifiable results and keeps any additional savings. Because it shifts the risk of program failure from taxpayers to investors, this mechanism has the potential to transform political discussions about expanding social services.”

However, this approach has already been likened to a ‘private finance initiative’ for social enterprises. The critical issue then becomes “he who pays the piper calls the tune”, and membership engagement becomes even more murky. Any steady income source can have its drawbacks. For example, according to the “crowding-out hypothesis”, an increase in one source of revenue, such as a government grant, can lead to a decrease in revenue from other sources, such as private donations (e.g., Weisbrod 1998).

So in answer to my original question, private investors stand to benefit while public sector budgets get cut (which could be easier to hide anyway through integrated care or ‘whole person care’ in the next parliament), and what’s at stake is that membership engagement gets worse as the social enterprises get bigger and bigger. But would this policy plank, in fact, prevent another Mid Staffs as Norman Lamb would perhaps like us to believe?

Selected readings

Allen, P., Townsend, P., Wright, J., Hutchings, A., Keen, J. (2012) Organizational Form as a Mechanism to Involve Staff, Public and Users in Public Services: A Study of the Governance of NHS Foundation Trusts, Social Policy & Administration, 46(3), June, pp. 239–257.

Alter, S.K. (2006) Social Enterprise Models and Their Mission and Money Relationships. In A. Nicholls (Ed.), Social Entrepreneurship: New Models of Sustainable Social Change: Oxford University Press

Birchall, J, Simmons, R (2004) The Involvement of Members in the Governance of Large-Scale Co-operative and Mutual Businesses: A Formative Evaluation of the Co-operative Group, Review of social economy, LXII, 4.

Bugg-Levine, A., Kogut, B., Kulatilaka, N. (2012) A New Approach to Funding Social Enterprises, January–Harvard Business Review, February, pp. 119-123.

Crifo, P, Forget, V.D. (2013) Think Global, Invest Responsible: Why the Private Equity Industry Goes Green, J Bus Ethics, 116, pp. 21–48.

Dees, J. G. (1998). Enterprising nonprofits, Harvard Business Review, pp. 55-67.

Hall, P.D. (1987) A historical overview of the private nonprofit sector, In The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook. Powell WW (ed.). Yale University Press: New Haven, CT; pp. 142–175.

Husted, B.W., Allen, D.B. (2007) Corporate Social Strategy in Multinational Enterprises: Antecedents and Value Creation, Journal of Business Ethics, 74, pp. 345–361

Piercy, N.F., Lane, N. (2009) Corporate social responsibility: impacts on strategic marketing and customer value, The Marketing Review, 9(4), pp. 335-360.

Weisbrod, B.A. (1998), The Nonprofit Mission and Its Financing: Growing Links Between Nonprofits and the Rest of the Economy, in To Profit or Not to Profit: The Commercial Transformation of the Nonprofit Sector, B. Weisbrod, ed. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–24.

So what of social enterprises and the NHS? Corporate social responsibility and marketing revisited.

Milton Friedman’s famous maxim goes as follows:

“there is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.”

The history of social enterprise in fact extends as far back to Victorian England (Dart, 2004; Hines, 2005). The worker cooperative is one of the first examples of a social enterprise. Social enterprises prevail through- out Europe, and are most notable in the form of social cooperatives, particularly in Italy, Spain and increasingly France (Mancino and Thomas, 2005).

More recently, Clare Gerada, the Chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners, yesterday on BBC’s “The Daily Politics”, stated the following:

“Privatisation is the moving of State resources into the for full profit or non-profit sectors. And – the previous debate is that ‘if you don’t pay for therefore it’s not privatisation – it is privatisation. The profit that Specsavers or Harmoni make, they will not go back into the State: they will go straight into the shareholders.”

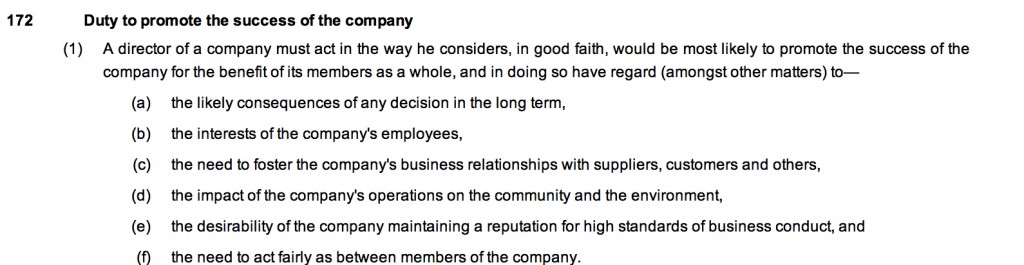

Currently, the position in English law is that the directors of every private limited company in law, whether they are called ‘social enterprises’ or not, have a statutory duty to the environment and stakeholders of their company. This is embodied in s.172 Companies Act (2006):

In an article by Rachel C. Tate, provocatively entitled, “Section 172 Companies Act 2006: the ticket to stakeholder value or simply tokenism?”, Tate argues as follows that stakeholder interests do not trump the interests of the company, i.e. to make profit. Interestingly. s.172 has no corollary in the common law.

“As highlighted, s172(1) formally obliges directors to consider stakeholder interests during the decision-making process. Yet, it is crucial to note that shareholder interests remain paramount. The interests of non-shareholding groups are to be considered only insofar as it is desirable to ‘(…) promote the success of the company for the benefit of its members.’17 A director will not be required to consider these factors beyond the point at which to do so would conflict with the overarching duty to promote company success. Stakeholder interests have no independent value in the consideration of a particular course of action.19 In addition, no separate duty or accountability is owed to the stakeholders included in the section.Thus, the duties of nurturing company success and having regard to the listed interests ‘(…) can be seen in a hierarchal way, with the former being regarded more highly than the latter.’21 Consequently, it would be wrong in principle to view s172 as requiring directors to ‘balance’ shareholders and stakeholder interests.22 These views are supported by industry guidance published on the effects of s172.”

“Social enterprises” are actually very hard to define. According to the United Kingdom (UK) government’s Department of Trade and Industry (2002), in the era of Tony Blair and Patricia Hewitt, a social enterprise is:

“a business with primarily social objectives whose surpluses are principally reinvested for that purpose in the business or in the community, rather than being driven by the need to maximise profit for shareholder and owners’”

Therefore, in theory, social ends and profit motives do not contradict each other, but rather have complementary outcomes, and constitute a ‘double bottom line’.

Nonetheless, the UK Government website contains a list of possible entities which could be described as ‘social enterprises’, namely:

- limited company

- charity, or from 2013, a charitable incorporated organisation (CIO is the new legal structure for charities)

- co-operative

- industrial and provident society

- community interest company (CIC)

- sole trader or business partnership

Note that in one of the vehicles, the limited company, as stated above, the primary duty of the directors is to promote success of the company. And that can be a “social enterprise”. Furthermore any contracts supplied to social enterprises can still still meet the definition of ‘privatisation’ above, not least because social enterprises are considered not to be wholly in the public sector (for example this EU definition, link here, where “Social enterprises are positioned between the traditional private and public sectors.”). Social enterprises do not meet the definition of what is typically in the public sector, by reference to the European System of Accounts 1995, link here. It is striking that the EU concede that one feature of social enterprises is a “significant level of risk”, so one has to question the long-term wisdom of competitive tendering contracts increasingly to social enterprises. Indeed, given that directors of English private limited companies are supposed to have due regard to wider “stakeholder” factors, one has to wonder quite what the point of the Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012 is. “Third Sector” magazine on 9 October 2012 reported that this enactment was not going that well:

“The Public Services (Social Value) Act could end up as a missed opportunity and more work needs to be done to encourage its use by commissioners and procurement professionals, delegates at the Labour Party conference heard. The act became law in March and places a duty on public bodies in England and Wales to consider “economic, social and environmental wellbeine in connection with public service contracts’! But at a fringe event hosted by the local infrastructure body Navca and the think tank ResPublica in Manchester, Hazel Blears, vice-chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Social Enterprise, said she was concerned that many local authorities would not give it the attention it deserved.”The wording is weak,”she said.”If they had to ‘take account of social value, that would have been a harder position.””

There has been concern that in social enterprises, whilst the external environment may be given prominence, the internal environment may suffer (Cornelius et al., 2008):

“Since many social enterprises exist predominantly to address social ends (one key feature of the triple bottom line), it could be argued that the prevalence of their CSR policy and practice require close investigation. Emanuele and Higgins (2000) con- tribute to this agenda by challenging the assumption that non-profit organisations can offer comparatively lower wages, because they are more pleasant places to work. The authors emphasise that employees in this sector are often second income earners, and therefore are less concerned with lower wages and reduced benefits more characteristic of the private sector. They highlight how the voluntary sector is often a job entry point for new employees, who later move on to other sectors offering more fringe benefits, better financial security and healthcare programmes. They conclude with the assertion that ‘‘we must begin to exert the same pressure for ‘corporate responsibility’ among non-profit employers, as we demand in the private sector’’ (Emanuele and Higgins, 2000: 92), implying that the social enterprise sector needs to treat its employees better. Distinguishing between external and internal CSR may be beneficial, with social enterprises clearly focusing upon serving communities and overlooking crucial internal human resource issues.”

Grimsby “Care Plus” has been, in fact, highly commended in the UK Social Enterprise Awards (link here). The national competition, organised by Social Enterprise UK, recognises excellence in Britain’s growing social enterprise sector. And yet it was recently reported that, “More than 800 staff employed by the Care Plus Group – which provides adult health and social care across North East Lincolnshire – are in consultation over cuts to their pay and conditions.” Lance Gardner, the Chief Executive of the organisation, is reported as saying, “There is a lot of goodwill here. Our staff go that extra mile for their patients and have a passion for caring. They would not want to see them suffer. I do not want to take our goodwill for granted.”

The story of what happened between UNISON and Circle Hinchingbrooke is of course well known now (link here):

“Christina McAnea, head of health at Unison, said Circle could “cream off nearly 50% of the hospital’s surpluses” which would make it “virtually impossible to balance the books”.

“This is a disgrace. Any surpluses should be going directly into improving patient care or paying off the hospital’s debt, securing its future for local people – not ploughed into making company profits.

“Instead patients and staff are facing drastic cuts. The hospital was already struggling, but the creep in of the profit motive means cuts will now be even deeper. And it is patients and staff that will pay the price.””

Of course, ‘corporate social responsibility’ (“CSR”), abbreviated to ‘people, planet, profit’ somewhat tritely, has clashed before with marketing, so it is no wonder that businesses should wish to look ‘socially responsible’ to seek competitive advantage. Corporates have long been criticised for using diversity as a marketing ploy, e.g. putting in their promotional literature photos of employees in wheelchairs to demonstrate they are disabled-friendly. Pitches from social enterprises are likely to come with them ‘a feel good factor’ in competitive tendering, and of course any pitch which complies with adding social value in keeping with the new legislation is perfect “rent-seeking” fodder. But at the end of the day they are a range of entities seeking to make money which does not necessarily get fed back into frontline care, but used to generate a surplus aka profit. In an outstanding essay by Anna Kim for the 8th Ashbridge Business School MBA award, the author writes:

“Many critics believe that most of so-called CSR activities are nothing but a deceptive marketing tool, such as greenwashing. Can British American Tobacco be a ‘responsible’ cigarette manufacturer? Is Nestle really moving towards social values, or simply trying to wash its image around the baby milk and other ethical issues by putting a Fairtrade label on its 0.2% of coffee product line? From the green policy of oil giants BP and Shell to the childhood obesity research fund of McDonald’s, the list of controversial CSR examples is not exhaustive.”

So what of social enterprises and the NHS – remember Milton Friedman and Clare Gerada….

References

Cornelius, N., Todres, M., Janjuha-Jivraj, J., Woods, A., and Wallace, J. (2008) Corporate Social Responsibility and the Social Enterprise, Journal of Business Ethics, 81, pp. 355–370.

Dart, R. (2004) The Legitimacy of Social Enterprise’, Nonprofit Management and Leadership ,14(Summer), pp. 411–424.

Department for Trade and Industry (2002) Social Enterprise: A Strategy for Success, available at http://www.seeewiki.co.uk/~wiki/images/5/5a/SE_Strategy_for_success.pdf .

Hines, F. (2005) Viable Social Enterprise – An Evaluation of Business Support to Social Enterprises’, Social Enterprise Journal, 1(1), pp. 13–28.

Mancino, A. and Thomas, A. (2005) An Italian Pattern of Social Enterprise: The Social Cooperative, Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 15(3), pp. 357–369.

The anti-social network

There are many advantages to a firm embracing twitter as part of their corporate strategy, and these have been discussed elsewhere extensively, including by @BrianInkster, @kilroyt, @bhamiltonbruce, @legalbrat, @colmmu, @NewLeafLaw, @LindaCheungUK and @LegalBizzle (= top (legal) commentator). @Miss_TS_Tweets has recently been given the go-ahead to take part in a corporate blogging exercise, and her recent experiences can be seen in her blog post as of yesterday. I am not going to talk about aspects of the ‘lawyers enjoying the tweet taste of success‘ described by Alex Aldridge, in his recent Guardian article. The tweeting community benefits from all contributors, ranging from @charonqc to @AshleyConnick, with differing but complementary perspectives. This all may be a far cry from what Mark Zuckenberg had originally conceived of in development and implementation of his ‘social network‘.

A medium-sized firm might be able to secure generic competitive advantages through their unique relationships in diverse practice areas and sectors (some of which might be extremely community-friendly such as social enterprises), but there always remains the ‘glocal‘ challenge – i.e. how to make such a fundamentally national or international approach work level at an individual basis within a particular town in England, Scotland or Wales, for example. My story here revolves around twitter, but it could equally apply to blogs such as this one. Equally, the strategy could be one focused on imparting knowledge including press releases and relevant publications (see, for example, the excellent @SJ_Weekly account which acts as a handle for the main journal/magazine). A robust synthesis of how to approach twitter in the corporate law was offered by them in a excellent thought-provoking post, “Tweet Forth And Multiply“, earlier this year. Jean-Yves Gilg, the Editor of Solicitors Journal, is well-known to be interested in this emerging area in corporate law.

Such educational initiatives via the social media can be extremely effective, even if the initial communication appears unidirectional but quickly allow prompt recriprocity (see for example the brand new educational initiative for law students, @TSL_Tweets and their rapidly-updated website). For example, Brian Inkster and Linda Cheung of the Institute of Directors, noticeably through @cubesocial, had emphasised the crucial importance of high quality people-relationship building, for example. However even the CubeSocial analysis has recently evolved into something further, with personal conversation management an achievable goal (as explained in Kim’s blog on 7 September 2011). This is essential for the ‘carryover’ effect for profitability of transactions, beyond the corporate billing of a single transaction, arguably.

The blog post of @Miss_TS_Tweets reinforces the view that corporate social media does not involve a network that is entirely “social”: it involves what I feel is an “anti-social network“. In her blogpost, Miss_TS_Tweets provides an example that you wouldn’t be necessarily be expected to wear a name badge at a social event outside work hours, so why should you be so identifiable if doing corporate twitter or acting as a corporate blogger? There are certainly issues about the infrastructure of the firm, its management and leadership, its customers/clients/competitors, its supply chain and network, its quality management, its process and quality management and its resource allocation which will influence the operational efficacy of implementation of a new corporate strategy within an organisation, whether in an incremental or revolutionary way.

It’s probably advisable for the anti-social network to developed, created and implemented according to well-known principles in management and leadership to maximise the chances of success. This is critically dependent on all members of the organisation, but this is dependent on realisation that the employee of the corporate firm cannot necessary be expected to do twitter 24/7 and needs some time to be in anti-social network (anti-social to work but social to ‘real immediates’, i.e. with personal friends and families only. Lawyers, like architects, journalists, physicians or surgeons, need their quality “me-time” too. Resource allocation and funding demonstrate a commitment to any particular innovation in a corporate, but paying somebody to be available 24/7 might unfortunately introduce some contractual obligation to be ‘on-call’ on twitter when the top priority should clearly be the nuts-and-bolts of practising the law like the drafting of contracts. Expecting somebody to tweet on a single merged work/personal account means that tweets become prominently designed to ‘play safe’, diminishing the breadth of substance to the tweets.

However, in the culture of the corporate firm embracing twitter, it is vital that corporate tweeters forge powerful relationships with all other stakeholders, which might include lay members of the general public, marketing and media analysts, lawyers, managers, others, or themselves. For this innovative approach to succeed, everybody’s input could be welcomed but in such a way where diversity is respected – this includes for different physical abilities, or hierarchy (e.g. trainee up to partner). The atmosphere has to be open.

The inherent issue with Twitter is that it is vehemenently innovative, such that participants must be able to feel they can make mistakes, and can take some risks. Corporate tweeters should not be penalised financially or otherwise if they make innocent mistakes, as a lot of damage can be done towards the enormous goodwill for the corporate tweeting to be a success. Giving improper advice would be wholly inadvisable for corporate tweeters, as they do indeed deserve to be disciplined by @sra_solicitors (and correspondingly @barstandards for the ‘other half’) for imparting incorrect advice which undermines the reputation of and confidence within the legal profession as a whole. The code of conduct for the routine operation of lawyers who are solicitors, including confidentiality issues, integrity or conflicts of interest (say), can be immediately applied to Twitter, which is merely just a genre of media. Corporate tweeters will perhaps need the help of senior people or specialists to advise constructively on this, in the same way a trainee would not be able to cough without someone noticing. That’s where a supportive education and training division, under the clever guidance of HR, might kick in to guarantee training (there possibly might be some actual skill to doing twitter effectively?), and robust encouragement is given for social media engagement.

The risk of such risky comments might indeed be mitigated by the corporate tweeter explaining that views are not necessarily thoe of the firm, and the corporate tweeters could be interspersed throughout the firm that an organisational change which is pro-twitter is not threatened by obstructive barriers within the organisation, the so-called “silo effect“. As there is much tacit knowledge potentially to be shared, such as the shared experiences of personal corporate tweeters in their personal accounts, it’s essential that these experiences are freely shared by established corporate tweeters and newcomers.

Risk-taking is a very tricky for those implementing a corporate twitter change to get their head around. If corporate tweeters, it’s pivotal that a ‘blame culture’ does not swoop down on the few member trying to make it work, and there is a balanced assessment of any successes (like @LegalTrainee actually achieving in improving quality and/or quantity of trainee recruitment through measurable analytics). There has to be clear authority, time scape and authority-to-act in the implementation of resources to make such a corporate twitter strategy work.

It might be helpful for ‘corporate twitter leaders‘ to be dispersed within the organisation, to ensure that the embracing of Twitter is a genuine one, and not a cosmetic one for purely marketing purposes (as can go wrong in disability accsss or corporate social responsibility). Individual motivation is clearly important but it is perhaps likely to work best if aligned with the overall goals of the organisation. This might be for example for a firm to have an excellent reputation and license-to-operate in something technologically -related, or prove that the firm can offer something different in traditional areas such as insolvency or company law.

Lawyers may want to take it in turns in covering their corporate tweeting commitments, and will not individually be available 24/7, particularly if they are in their 20-40s with young families; however clients, particularly in this brave new world including alternative business structures, may wish to feel that there is someone there, and Twitter could be powerful in establishing this even if it is actually merely an illusion. The trick would then to be to make a partly anti-social network look wholly social at a superficial glance, at the very least.

So, having taken the plunge to make a law firm succeed in the brave new world of Twitter, as indeed Inksters and Silverman Sherliker (@London_Law_Firm), the firm of Chris Sherliker and Jennie Kreser (@pensionlawyeruk), have proved, it would be tragic to see such an innovative strategy literally implode through lack of direction of management. This is unfortunately where lawyers, including partners, may have to concede that they can’t do everything; in much in the same way social media gurus will go nowhere without the help of their corporate tweeting colleagues.