Home » Posts tagged 'safe staffing'

Tag Archives: safe staffing

Why speaking out safely and safe staffing are important moral issues for the NHS

A culture where staff and patients can speak openly about successes and failures in the NHS, as well as more specifically on safe staffing issues, is essential for the NHS to move forward. Perhaps most intriguingly, the failure of the English law to cherish the need to ‘speak out safely’ in the NHS can be tracked back to four Acts of parliament ranging in the last thirty years uptil the present day.

A culture where staff and patients can speak openly about successes and failures in the NHS, as well as more specifically on safe staffing issues, is essential for the NHS to move forward. Perhaps most intriguingly, the failure of the English law to cherish the need to ‘speak out safely’ in the NHS can be tracked back to four Acts of parliament ranging in the last thirty years uptil the present day.

The focus recently has tended to be about whether things would or would not work, and have either been economic or regulatory in perspective.

The Health and Social Care Act (2012), all 493 pages of it, is fundamentally a statutory instrument which proposes the mechanism for competitive tendering in the NHS (through the now infamous section 75), the financial failure regimes, and the regulatory mechanisms to oversee an emboldened market. It is therefore a gift for the corporate lawyers. It does, though, successfully mandate in law the abolition of the National Patient Safety Agency in s. 281.

There is therefore not a single clause on patient safety in this voluminous document. Patients, and the workforce of the NHS, are however at the heart of the NHS.

The language has been overridden by economic concepts misapplied. “Sustainability” is a very good example. Too often, sustainability has been used as a synonym for ‘maintained’, usually as a precursor for an argument about shutting down NHS services. It quite clearly from the management literature means a future plan of an entity with due regard to its whole environment.

Discussion about regulators can lead to a paralysis of policy.

No sanctions against Doctors have yet been made by the GMC over Mid Staffs, which does rather appear to be a curious paradox given the widespread admissions of undeniably ‘substandard care’. The regulator needs to have the confidence of the public too. One of their rôles is commonly cited to be to ‘protect the public‘, and this is indeed enshrined in law under s.1(1A) Medical Act (1983).

It is of regulatory interest how precisely the GMC ‘protected the public’ over Mid Staffs, whatever the operational justifications of their legal processes in this particular case.

Strictly speaking, promoting the safety of the public might include promoting the ability of clinical staff ‘to speak out safely’, and this could be an important manifestation of a core legal objective of that particular regulator?

On the other hand, confidence in the regulator is never achieved by any regulator on the basis of conducting “show trials“. This can be always be a big danger, as GMC cases on occasions attract wider general media interest. This will, of course, be to the detriment of defendants with complicated mental health issues.

There is little fundamental dispute about the need for clinicians to be open about medical errors in their line of work. Even the Compensation Act (2006), if you need to cite the law, provides that an apology does not mean an admission of liability in section 2.

There can be disputes about upon whom the ‘duty of candour’ should fall, whether this might be the Trust or an individual clinician, and who is going to enforce it.

But just because there are legal issues about the practicality of it, a civilised society must use the law to reflect the society it wishes for.

There is currently, for example, a statutory duty for company directors to maximise shareholder dividend of a company with due regard to the environment (as per s.172 Companies Act (2006)). There is no corresponding duty for hospitals to minimise morbidity or mortality on their watch.

“Whistleblowers” are often accused of raising their complaints too late.

Whistleblowers can find themselves becoming alien for NHS organisations they are devoted to.

Often, there is a ‘clipboard mentality’ where ‘colleagues’ will raise issues to discredit the whistleblowers. Often these ‘colleagues’ are protecting their own back. Regulators should not collude in such initiatives.

And yet it is clear that the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998 fails both patients and whistleblowers.

There are ways to bring about change. Most often regulation is not in fact the answer.

A cultural change is definitely needed, and this appears to go beyond corrective mechanisms through English jurisprudence.

This in the alternative requires staff and patients from within the NHS prioritising speaking out safely.

The information which can be provided by ‘speaking out safely’ should be treated like gold dust – and be used for improvement for patient safety in the NHS, as well as in the performance management of all clinicians involved.

Arguably the precise information is much more useful than an estimate such as the ‘hospital standardised mortality ratio’ which does not operate on a case-by-case basis anyway.

A new-found desire to speak openly might also include a wider policy discussion about safe staffing levels. Regulating a minimum staffing level might shut down important debates about ‘what is safe’, such as the skill mix etc. And yet there are equally important issues about how to prioritise this in the law.

The hypothesis that unsafe staffing levels or poor resources generally lead to poor patient safety in some foci of the NHS has not been rejected yet. It’s essential that managers allow staff to be listened to, if they have genuine concerns. Not everything is vexatious.

Most of all, society has to be seen to reward those people who have been strong in putting the patient first.

Small steps such as Trusts in England supporting the Nursing Times’ “Speak Out Safely” campaign are important.

Critically, such support is vital, whatever political ideology you hail from.

It could well be that the parliamentary draftsmen produce a disruptive innovation in jurisprudence, such that speaking out safely is correctly valued in the English law, and thenceforth in the behaviour of the NHS.

Hopefully, an initial move with the recent drafting of a clause of the “legal duty of candour” in the Care Bill (2013) we will begin to see a fundamental change in approach at last.

NHS 247 – don’t mention the Staffing!

According to a recent newspaper article, the latest workforce statistics obtained by Nursing Standard magazine from the Health and Social Care Information Centre reveal that there are 348,311 nurses, midwives, school nurses and health visitors working either full-time or part-time in England. That is 2,991 fewer full-time posts than when the coalition government came to power. United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust, Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Burton Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust are “plugging gaps” by hiring nurses from abroad. Basildon and Thurrock is looking to recruit 200 nurses from the Philippines and Spain. The international campaigns launched by the trusts reflect a growing trend to search beyond the UK for staff.

According to a recent newspaper article, the latest workforce statistics obtained by Nursing Standard magazine from the Health and Social Care Information Centre reveal that there are 348,311 nurses, midwives, school nurses and health visitors working either full-time or part-time in England. That is 2,991 fewer full-time posts than when the coalition government came to power. United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust, Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Burton Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust are “plugging gaps” by hiring nurses from abroad. Basildon and Thurrock is looking to recruit 200 nurses from the Philippines and Spain. The international campaigns launched by the trusts reflect a growing trend to search beyond the UK for staff.

According to reports from Whiston, management staff have defended their recruitment policy after it transpired that Whiston Hospital’s A&E was understaffed by around eight per cent. An investigation by the BBC found that 11 of the 131 positions at the hospital’s casualty department remained unfilled. It is believed the shortfall is regularly made up by employing bank and agency staff, in line with other reports from around the country. The revelations about staffing levels, made following a Freedom of Information Act request, have unsurprisingly prompted nursing leaders to criticise current staffing levels. Meanwhile, according to reports from Croydon, a staffing crisis at Croydon University Hospital A&E has left it with the second largest shortfall of permanent employees in the country. That ward has a third fewer permanent workers than its NHS trust believes it needs, with the biggest gap in the supply of nurses. Croydon Health Services NHS Trust employs 151 permanent A&E staff, a shortfall of 48. Only Barking, Havering and Redbridge University Hospitals NHS Trust had a bigger deficit of staff, according to official statistics obtained through Freedom of Information requests. The trust stressed holes were plugged with temporary and agency staff, although these typically cost more than full-time employees. It claimed employing temporary staff did not impact on standards of care, unsurprisingly.

Last week, the Royal College of Physicians published its “Future Hospital Commission” report (“Report”). Generalist and specialist care in the future hospital came under some scrutiny in this report, but not in a way which addresses where there can possibly be more Doctors ‘on the ground’. Generalist care includes acute medicine, internal medicine, enhanced care and intensive care. Specialist components of care will be delivered by a specialist team who may also contribute to generalist care. A critical question is, in the average DGH, which of the ‘specialists’ are going to chip in with the acute general medical take. Currently, it is not uncommon for respiratory, gastroenterology and endocrinology physician consultants to run the acute general medical take, but (generally) neurologists and cardiologists do not take part.

“Patients should receive a single initial assessment and ongoing care by a single team. In order to achieve this, care will be organised so that patients are reviewed by a senior doctor as soon as possible after arriving at hospital. Specialist medical teams will work together with emergency and acute medicine consultants to diagnosis patients swiftly, allow them to leave hospital if they do not need to be admitted, and plan the most appropriate care pathway if they do.”

The “24/7″ aspect of ‘Future Hospitals’ is emphasised in various places in the report, for example:

“Acutely ill medical patients in hospital should have the same access to medical care on the weekend as on a week day. Services should be organised so that clinical staff and diagnostic and support services are readily available on a 7-day basis. The level of care available in hospitals must reflect a patient’s severity of illness. In order to meet the increasingly complex needs of patients – including those who have dementia or are frail – there will be more beds with access to higher intensity care, including nursing numbers that match patient requirements. There will be a consultant presence on wards over 7 days, with ward care prioritised in doctors’ job plans. Where possible, patients will spend their time in hospital under the care of a single consultant-led team. Rotas for staff will be designed on a 7-day basis, and coordinated so that medical teams work together as a team from one day to the next.”

Against this is the backdrop of the Nicholson “efficiency savings”, as reported (for example) here in the Guardian:

“The prime minister, David Cameron, his health secretary, Andrew Lansley, and the NHS’s most senior figures have all stressed that the government’s drive to make £20bn of efficiency savings in England by 2015 should not prompt hospitals and primary care trusts to cut services provided to patients. Instead, they say, the money should be saved through reducing bureaucracy, ending waste, adopting innovative ways of working and restructuring services.

Yet the growing evidence from the NHS is that its frontline is being cut, and that NHS organisations are doing what they were told not to do – interpreting efficiency savings as budget and service cuts. While restricting treatments of limited clinical value – such as operations to remove unsightly skin – is uncontroversial, reducing patients’ access to drugs, district nurses, health visitors or forms of surgery they need to end their pain arouses huge concern.”

Shaun Lintern, in a typically excellent article in the Health Services Journal, threw some light on this in relation to the report by Professor Sir Bruce Keogh, in July 2013:

“The NHS has little idea whether staffing levels at English hospitals are safe, Keogh review panel members have admitted. The report by NHS England medical director Sir Bruce Keogh said data for eight of the 14 hospital trusts examined by the review suggested there was no problem with nursing levels on wards.But when the review teams carried out their inspections they found “frequent examples of inadequate numbers of nursing staff in some ward areas”. In his report Sir Bruce said: “The reported data did not provide a true picture of the numbers of staff actually working on the wards.” The review suggests high level data on workforce levels may present an unrealistic impression of staff available on hospital wards on any given shift. This could lead to NHS trusts drawing false assurances from workforce data while their wards go understaffed. At several of the trusts examined the review team found staff feeling unable to voice their concerns to senior managers.”

Julie Bailey and #CuretheNHS, as well as a number of prominent patient groups such as #PatientsFirstUK, as well as certain regulatory authorities such as the #CQC, have all emphasised the need for ‘safe staffing’ for the NHS to succeed. Prof Sir Brian Jarman has time-and-time-again emphasised the pivotal impact of safe staffing on the hospital standard mortality ratio, as for example in this seminal article from the BMJ in 1999, on page 1517:

“In model A higher hospital standardised mortalityratios were associated with higher percentages of emergency admissions, lower numbers of hospital doctors per hospital bed, and lower numbers of general practitioners per head of population. The numbers ofhospital doctors of different grades were also considered as explanatory variables, but total doctors per bed was found to be the best predictor.”

A symptom of a poorly staffed NHS (in certain autonomous units) would be the system completely falling apart from the strain of increased numbers during the Winter period. A ‘solution’ proposed by NHS England has been some of £2.4 billion surplus will be plugged into a ‘quick fix’ of the situation, and/or hospitals can employ temporary bank staff. This may in the short term attempt to mitigate against a dangerous situation. According to the GMC(UK)’s “Good medical practice” (at point 56):

“56. You must give priority to patients on the basis of their clinical need if these decisions are within your power. If inadequate resources, policies or systems prevent you from doing this, and patient safety, dignity or comfort may be seriously compromised, you must follow the guidance in paragraph 25b.”

Many senior consultants do not wish to speak out safely currently against poor resources. This is reflected in this tweet/comment by Dr Kim Holt:

This further emphasises the need for (all) staff to speak out safely against dangerous clinical care (hence the critical importance of the “Nursing Times Speak Out Safely” campaign.) From the consultant physician front, with the ‘input’ from operations and flow managers, there are currenltly reports of insufficient doctors and nurses being able to see patients in A&E in a timely fashion. It seems that the response to this, while NHS managers have remained consistently immune from materially significant blame for poor clinical care, has been for medical consultants to shunt patients, including vulnerable frail patients, out of A&E into MAU (or even, at worst, medical outlier wards), without patients having ever been clerked. That would be therefore direct evidence of a ‘gaming’ managerial culture directly impacting on how NHS consultants on the ‘shop floor’ have to react in the face of cuts and pressures from clinical demand. Whilst it might be sexy for all politicians and the Royal College of Physicians of London to talk about 24/7, no government minister has gone public to say how they will literally achieve ‘more for less’. Where will the extra money come from? Presumably existing staff will have to do more work for the same pay, and still have to comply with the law governing working (i.e. the Working Time Regulations passporting the European Time Directive).

This further emphasises the need for (all) staff to speak out safely against dangerous clinical care (hence the critical importance of the “Nursing Times Speak Out Safely” campaign.) From the consultant physician front, with the ‘input’ from operations and flow managers, there are currenltly reports of insufficient doctors and nurses being able to see patients in A&E in a timely fashion. It seems that the response to this, while NHS managers have remained consistently immune from materially significant blame for poor clinical care, has been for medical consultants to shunt patients, including vulnerable frail patients, out of A&E into MAU (or even, at worst, medical outlier wards), without patients having ever been clerked. That would be therefore direct evidence of a ‘gaming’ managerial culture directly impacting on how NHS consultants on the ‘shop floor’ have to react in the face of cuts and pressures from clinical demand. Whilst it might be sexy for all politicians and the Royal College of Physicians of London to talk about 24/7, no government minister has gone public to say how they will literally achieve ‘more for less’. Where will the extra money come from? Presumably existing staff will have to do more work for the same pay, and still have to comply with the law governing working (i.e. the Working Time Regulations passporting the European Time Directive).

Whilst their Report is to be welcomed, the Royal College of Physicians have effectively delivered a ‘motherhood and apple pie’ document for Government. It sounds nice and does not even address issues relating to the home patch? One of them will be for the Council of the College to consider whether it wishes for ‘specialist’ Consultants to ‘chip in’ with the acute medical take 24/7. They have after all at some stage passed the Diploma of the Royal Colleges of Physicians (UK)?

Meanwhile, for all the methodological criticisms of Jarman’s work, it can only be assumed that he genuinely wishes to improve the quality of care of NHS hospitals in England, and that he sincerely wishes to prevent the staggering distress of those foci of poor care where evidenced previously in the NHS. His words, on @RoyLilley’s “NHSmanagers.network” blog, could not have been clearer.

Safe staffing, Keogh and the Nursing Times “Speak out safely” campaign

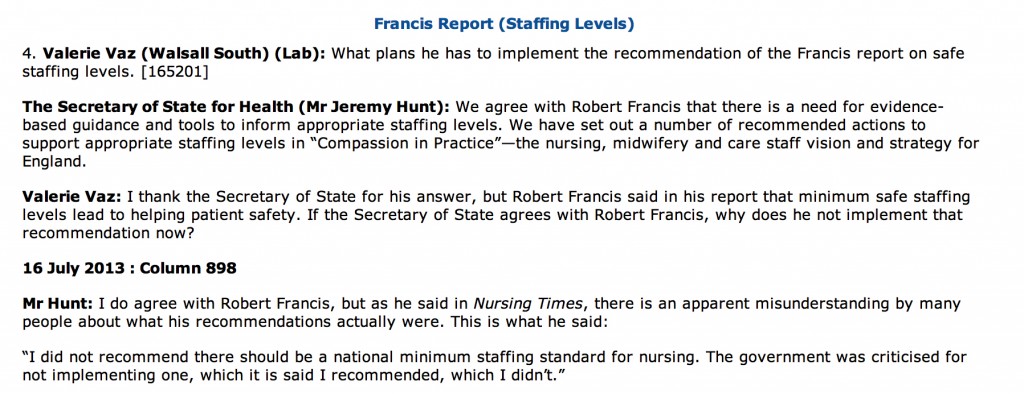

Despite clear differences in opinion about what has happened in the past, patient groups, Andy Burnham, Jeremy Hunt, the Unions, bloggers, experts, other patients, whistleblowers, and relatives at face value appear to want the same thing: a safe NHS where you do not go into hospital as a risky event in itself. The issue of safe staffing in nursing has become the totemic pervasive core issue of secondary care safety, and no amount of parliamentary time one suspects will ever do proper justice to it. In reply to a question from Valerie Vaz, who is herself on the Health Select Committee, Jeremy Hunt immediately quoted the Nursing Times and the Francis Report (from Tuesday 16 July 2013):

The aim of the Nursing Times’ Speak Out Safely (SOS) campaign is to help bring about an NHS that is not only honest and transparent but also actively encourages staff to raise the alarm and protects them when they do so.

They want:

- The government to introduce a statutory duty of candour compelling health professionals and managers to be open about care failings

- Trusts to add specific protection for staff raising concerns to their whistleblowing policies

- The government to undertake a wholesale review of the Public Interest Disclosure Act, to ensure whistleblowers are fully protected.

A very impressive gamut of organisations have supported the “Nursing Times Speak Out Safely” campaign, including Cure the NHS, the Florence Nightingale Foundation, the Foundation of Nursing Studies, Mencap Whistleblowing Hotline, Patients First, Public Concern at Work, Queen’s Nursing Institute, Royal College of Nursing, Unite (including the Community Practitioners and Health Visitors Association and Mental Health Nurses Association), and WeNurses. Also, for example, according to the Royal College of Midwives, maternity staff must be able to publicly raise concerns about the safety of mother and babies without fear of reprisal from their employers, according to the Royal College of Midwives. This college has been the latest organisation to support the Speak Out Safely campaign. They are calling for the creation of an open and transparent NHS, where staff can raise concerns knowing they will be handled appropriately and without fear of bullying.

The pledge of the Speak Out Safely campaign of Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust is a pretty typical example of the way in which this campaign has successfully reached out to all people who have the focused aspiration of patient safety.

“This trust supports the Nursing Times Speak Out Safely campaign. This means we encourage any staff member who has a genuine patient safety concern to raise this within the organisation at the earliest opportunity.

Patient safety is our prime concern and our staff are often best placed to identify where care may be falling below the standard our patients deserve. In order to ensure our high standards continue to be met, we want every member of our staff to feel able to raise concerns with their line manager, or another member of the management team. We want everyone in the organisation to feel able to highlight wrongdoing or poor practice when they see it and confident that their concerns will be addressed in a constructive way.

We promise that where staff identify a genuine patient safety concern, we shall not treat them with prejudice and they will not suffer any detriment to their career. Instead, we will support them, fully investigate and, if appropriate, act on their concern. We will also give them feedback about how we have responded to the issue they have raised, as soon as possible.

It is not disloyal to colleagues to raise concerns; it is a duty to our patients. Misconduct or malpractice should never be tolerated, while mistakes and poor practice may reveal a colleague needs more training or support, or that we need to change systems or processes. Your concerns will be dealt with in an open and supportive manner because we rely on you to ensure we deliver a safe service and ensure patient safety is not put at risk. We also want this organisation to have the confidence to admit to mistakes and to use them as learning opportunities.

Whether you are a permanent employee, an agency or temporary staff member, or a volunteer, please speak up when you feel something is wrong. We want you to be able to Speak Out Safely.”

The Keogh report is in its entirety is an apolitical report, and is very constructive. It identifies problems which Keogh’s team (which currently consists of some brilliantly talented Clinical Fellows) have a realistic chance of tackling. Despite criticisms that Hunt has turned up the ‘political heat’ on this issue, there is a feeling that Labour and Andy Burnham MP should either ‘put up or shut up’. If you park aside the mudslinging over the 13,000 ‘needless deaths’ from irresponsible journalism from parts of the media, the current Department of Health has surely begrudgingly have to be given some credit for instigating appropriate responses such as the Keogh review, and a Chief Inspector of Hospitals. There has been a real effort to clear up the methodology of estimating mortality figures, and while methodology issues will persist, an approach which fully involves and acknowledges the views of patients, whatever their political affiliations, is the only way forward.

As an immediate response to the terms of reference to protect patients from harm, Keogh thrust high up the importance of instigating changes to staffing levels and deployment; and dealing with backlogs of complaints from patients. Keogh identified a basic deficiency in effective performance management in the 14 NHS Trusts under investigation, and these basic performance management techniques are now commonplace in successful corporates. These constitute understanding issues around the trust’s workforce and its strategy to deal with issues within the workforce (for instance staffing ratios, sickness rates, use of agency staff, appraisal rates and current vacancies) as well as listening to the views of staff; Keogh laid down a number of “ambitions”. In ambition 6, Keogh argued that nurse staffing levels and skill mix should appropriately reflect the caseload and the severity of illness of the patients they are caring for and be transparently reported by trust boards.

The review teams especially found a recurrent theme of inadequate numbers of nursing staff in a number of ward areas, particularly out of hours – at night and at the weekend. This was compounded by an over-reliance on unregistered staff and temporary staff, with restrictions often in place on the clinical tasks temporary staff could undertake. There were particular issues with poor staffing levels on night shifts and at weekends. There were also problems in some hospitals associated with extensive use of locum cover for doctors.This observation is interesting as at the end of day an over-reliance on agency staff in both private and public sector from a performance management perspective will guarantee the NHS not getting the best out of its staff, and will further impede hospital CEOs from meeting their ‘efficiency targets’. As set out in the “Compassion in Practice”, Directors of Nursing in NHS organisations should use evidence-based tools to determine appropriate staffing levels for all clinical areas on a shift-by-shift basis. This means that a statutory minimum may be the inappropriate sledgehammer for an important nut. It is proposed that boards should sign off and publish evidence-based staffing levels at least every six months, providing assurance about the impact on quality of care and patient experience. The National Quality Board will shortly publish a ‘How to’ guide on getting staffing right for nursing. Whilst it is easy to argue against a national minimum number for nurses, as one can easily argue that it might encourage a race-to-the-bottom with managers gaming the system such that they only provide the minimum to run their Trust, most people, irrespective of the strong-held and important views of professionals within the nursing profession, believe that running a service with too few nurses is simply too risk for the remaining nurses. At times of high demand, Trusts need to be adaptable and flexible enough to cope, as anyone who has been involved in acute care in national emergencies has been involved (“critical incidents”).

Staffing was a recurrent pathology in the 14 Trusts under investigation. In Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, it was argued that the Trust needs to review current staffing levels for nursing and medical staff. In Buckinghamshire NHS Trust, the panel had a concern over staffing levels of senior grades, in particular out of hours. In Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust, it was found that staffing in some high risk wards needs urgent review. For the Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust, inadequate qualified nurse staffing levels were identified on some wards, including two large wards which needed to be reviewed in light of concerns raised by the panel. For North Lincolnshire and Goole NHS Foundation Trust, there were concerns over the staffing of key elements of acute care, including recruitment of staff and maintenance of adequate staffing levels and skill mix on the wards. In North Cumbria University Hospital NHS Trust, inadequate staffing levels was identified, as well as an over-reliance on locum cover in some areas of the Trust.

For East Lancashire NHS Trust, the review team considered that staffing levels were low for medical and nursing staff when compared to national standards. Registrar cover and medical staffing in the emergency department was considered poor (this is medical ‘code’ for an overreliance on juniors at Foundation level), and levels of midwifery staff were considered poor too. Certain clinical concerns raised by staff have not been addressed, including known high mortality at the weekends. Whilst some of these actions will take longer to address entirely, assurance in respect of patient flows in A&E and concerns over staffing in the midwifery unit had already been sought by the CQC. For Medway NHS Foundation Trust, a top priority was made of teviewing staffing and skill mix to ensure safe care and improve patient experience, emphasising yet again that there might be false security to be derived from just looking at the overall number. For Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, significant concerns around staffing levels at both King’s Mill Hospital and Newark Hospital and around the nursing skill mix, with trained to untrained nurse ratios considered low, at 50:50 on the general wards. Finally, for United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust, inadequate staffing levels and poor workforce planning particularly out of hours were discovered; concern over the low level of registered nursing staff on shifts in some wards during the unnannounced visit out of hours was escalated to CQC. Further investigation is underway.

This is a matter for all the political parties to get to the bottom of urgently. Party affiliations and tribal politics threaten real substantial progress in this area for all those who work in this area. This is not the time for energised disputes about political leadership in organisations. This is most certainly a time for action. Both the Francis report into the failures of care at Mid Staffs, and The Keogh Review into high hospital mortality rates, highlight how important the right skills mix and sufficient numbers of staff are to providing top quality care. Having the right staff cover is increasingly important out of hours – at evenings and weekends. With all political parties urging a need to work ‘harder and smarter’, or generally under the rubric of working more ‘efficiently’, this is a harsh climate, due to shrinking budgets as the cost of healthcare rises, and because of demands for £20 billion of so-called efficiency savings. Of course, the public are not involved in a genuine public debate at the moment which does not depict the ageing population as a budgetary ‘burden’ on the society, instead pumping in a carefree way billions into the HS2 project with its unclear business case. Billions more have been wasted on a chaotic, unnecessary top down reorganisation of the NHS; the National Audit Office has latterly criticised for the Government for going ‘over-budget’ on these bureaucratic reforms. Frontline staff are obviously rightly angry that this is money that they feel this is money that could and should have gone towards actually caring for patients.

The tragedy is that it really feels as if the NHS has never known, or unlearnt at great speed, basic performance management. One can argue until the cows come home how in this managerial-heavy approach to the NHS such management is extremely poorly done in such a way the CIPD would feel ashamed at possibly. The NHS will deserve to have problems in recruiting the best managers for the NHS so long as the climate of performance management, perhaps affected by an obsession for targets, remains deeply unappealing. It is recognised that good performance management helps everyone in the organisation to know hat the organisation is trying to achieve, their role in helping the business achieve its goals, the skill and competencies they need to fulfil; their role, the standards of performance required, how they can develop their performance and contribute to development of the organisation, how they are doing, and when there are performance problems and what to do about them. The general consensus is that, if employees are engaged in their work they are more likely to be doing their best for the organisation. An engaged employee is someone who:

The actual reality is that currently spending pressures mean that many health workers, sadly, are losing their jobs. Financial pressures are building up in the NHS just as the demand for healthcare and its cost is rising – trusts are being asked to make unconscionable savings. Trusts such as Barts Healthcare are in severe trouble, and the contribution of the failed policy of PFI is a massive scandal in itself. This perfect storm will hit standards of patient care hard, and is the direct consequences of decisions made by various recent governments – not by hardworking NHS staff. The only thing which is set up to work in the Act, apart from outsourcing (section 75) and raising massively the private cap (section 164(1)(2A)) of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 is the legal precision of the various failure or insolvency regimes. In any other sector, this would fall under wrongful or fraudulent trading. Except, it’s the NHS. It does economic activity in a very special way. As the shift in economic and political power shifts from a state well-funded comprehensive healthcare system to a fragmented disorganised piecemeal private integrated system in the next few decades, patient safety must take priority even if not a top priority seemingly in business plans. Initiatives such as the Nursing Times ‘Speak out Safely’ campaign is one of those vital ‘checks and balances’ to ensure that the NHS is working with and for patients and not against them. This means the NHS valuing staff as a top priority, as social capital is the most important thing in any organisation.