Home » Posts tagged 'risk'

Tag Archives: risk

You need risk to live well with dementia

“Risk” is one of those entities which bridges the financial world with law and regulation, psychology or neuroscience. The simplicity of the definition of it in the Oxford English Dictionary rather belies its complexity?

It was a pivotal part of my own Ph.D. in the early diagnosis of the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia, awarded by the University of Cambridge in 2001. I was one of the very first researchers in the world to identify that ‘risk seeking behaviour’ is a key part of the presentation of many of these individuals, against a background of quite normal other psychological abilities and investigations including brain neuroimaging scans.

‘You need to break eggs to make an omelette’ is one formulation of the notion that you have to be able to make mistakes to achieve an overall goal. That particular sentence is, for example, used to convey the way in which you might have to put up with ninety nine turkeys before striking gold with one truly innovative idea. ‘Nothing ventured nothing gained’ is another slant of a similar idea. Interestingly, this phrase is often attributed to Benjamin Franklin. Franklin has an established reputation of his own as a ‘conceptual innovator‘.

It’s also a very interesting policy document on risk in dementia from the UK Department of Health, from 10 November 2010, a really useful contribution. This guidance was commissioned on behalf of the Department of Health by Claire Goodchild, National Programme Manager (Implementation), National Dementia Strategy. The guidance was researched and compiled by Professor Jill Manthorpe and Jo Moriarty, of the Social Care Workforce Research Unit, King’s College London.

Prof Alistair Burns, England’s clinical lead for dementia, has written a very focused and relevant Foreword to this piece of work. Here Alistair is, pictured with me earlier this week at the Dementia Action Alliance Annual Conference hosted in Westminster, London (“DAA Conference”). The event was a positive celebration of the #DAACC2A, “Dementia Action Alliance Carers’ Call to Action”, which embodies a movement where, “carers are acknowledged and respected as essential partners in care, and are supported with easy access to the information and the advice they need to assist them in carrying out their role.”

Risk enablement, or as it is sometimes known, positive risk management, in dementia involves making decisions based on different types of knowledge. However, people living with dementia and caregivers, quite often an eldest child or spouse, can handle risk in different ways. I feel that understanding living well with dementia is only possible through understanding the background to a person living with dementia, and his or her interaction with the environment. I’ve indeed written a comprehensive book on it, and I am in the process of writing a second book on it, which brings under the spotlight many of the key stakeholders, I believe, who contribute to “dementia friendly communities”.

Risk enablement is based on the idea that the process of measuring risk involves balancing the positive benefits from taking risks against the negative effects of attempting to avoid risk altogether. For example, the report cites the example of the risk of getting lost if a person with dementia goes out unaccompanied needs to be set against the possible risks of boredom and frustration from remaining inside. There are clearly various components of risk which might affect a person living with dementia. Risk engagement therefore becomes a constructive process of risk mitigation, an idea highly familiar to the law and regulation through the pivotal thrust of ‘doctrine of proportionality‘, that legislation must be both necessary and proportionate.

Risk enablement, it is argued, goes far beyond the physical components of risk, such as the risk of falling over or of getting lost, to consider the psychosocial aspects of risk, such as the effects on wellbeing or self-identity if a person is unable to do something that is important to them, for example, making a cup of tea. Therefore, the report proposes that “risk enablement plans” could be drawn up which summarise the risks and benefits that have been identified, the likelihood that they will occur and their seriousness, or severity, and the actions to be taken by practitioners to promote risk enablement and to deal with adverse events should they occur. These plans need to be shared with the person with dementia and, where appropriate, with his or her carer or caregiver. Thus advancing the policy construct of ‘personalisation’ offering choice and control, risk assessment tools are envisaged by the authors to help support decision making, and should include information about a person with dementia’s strengths and of his or her views and understanding about risk. Risk could apply to making a cup of tea, or going for a walk. We know that people living with dementia handle risks in different ways. For some people, a person living with dementia excessively walking beyond a local jurisdiction might be a known problem. For all the different causes of dementia medically, and for all the different ways in which individuals react to a dementia at different stages of the condition, a person can live with dementia in a sharply distinctive way.

Risk therefore in a hugely meaningful and substantial way has moved away from the “safety first” circles? And it fundamentally will depend on how an unique person living with his or her dementia embraces the environment in reality.

The idea that you need risk to live well with dementia is brought into sharp focus here by Chris Roberts, a friend of mine, speaking at the DAA Conference. I have recently begun to take risks in a highly enjoyable game for my #ipad3, which Chris indeed introduced me to, called, “Real Racing 3″. Here, Chris also talks about the crass way in which he was originally told his diagnosis, and lack of information about his condition given at the time of diagnosis. Therefore, Chris, I feel, brings into sharp focus a number of problem areas, which hopefully Baroness Sally Greengross and colleagues will address in a new five year strategy for England for 2015-20.

Outsourcing has become a policy drug, and they need to kick the habit

If you don’t want to do something, you pay somebody else to do it. Hopefully you pay them peanuts. Doesn’t matter if the actual product or service is a bit shit. Or you could allow somebody else to do it under your identity still. Everyone thinks you’re the author it. But you pay that person a massive mark up so they make a tidy profit. Everyone’s a winner.

For this Government under Frances Maude, Chris Grayling and Jeremy Hunt, “outsourcing” is a drug. They need more of it to get the same kick (an increasing degree of tolerance), and if they don’t outsource something they get nasty withdrawal symptoms. Outsourcing is consider a useful step along the way to privatisation, and of course many less intelligent people have been arguing that the Health and Social Care Act is not privatisation. It is clearly privatisation if you outsource what should be a state-run health service into private hands for profit or surplus, and it is privatisation if you allow up to 50% of income to come from private sources. Both are new developments under this Government. Everyone’s a winner here – especially the hedge funds who are the major institutional shareholders of the private healthcare companies, the private companies who can find through slick procurement bids willing funders, and, of course management consultants, accountants and lawyers who can send a NHS Trust into one of the many detailed insolvency and failure régimes outlined in the Health and Social Care Act (2012). Mind you, there’s not a single clause on ‘safe staffing requirements’ in NHS Trusts, as a necessary and proportionate ‘check and balance’ on overzealous managers inflicting ‘efficiency cuts’ to frontline doctors and nurses. “More for less” is the mantra, and, with the Secretary of State now legally not obligated for the NHS for the first time (but responsible for ‘special measures’ presumably so that he can take control of both lack of patient safety in extreme measures and which private sector advisors can advise), outsourcing is not the next scandal waiting to happen. It is well and truly alive. While the ideological concern has been ‘privatising profits, socialising losses’ a concept coined by Andrew Jackson as far back as 1834 (and maybe the Royal Mail and RSB may be worthy examples to consider here), there is now an added dimension that foreign multinationals can raid the NHS, take over vast bits of it, and their registered offices for tax reasons might be abroad. The line of attack has always been that Doctors and nurses contribute nothing to the ‘wealth’ of this country not being wealth creators (footballers possibly do contribute more in a similar way to “Top Gear” by being potent foreign merchandising exports inter alia). The massive irony is that the tax from profits ends up in foreign jurisdictions, and contribute to the economy of those countries not ours. The resolution of the US-EU Free Trade Agreement, which may or may not include the NHS, will be important here, and there’s still no answer to Debbie Abrahams’ inquiry to my knowledge:

Debbie Abrahams (Oldham East and Saddleworth) (Lab): Will the Prime Minister confirm that the NHS is exempt from the EU-US trade negotiations?

The Prime Minister: I am not aware of a specific exemption for any particular area, but I think that the health service would be treated in the same way in relation to EU-US negotiations as it is in relation to EU rules. If that is in any way inaccurate, I will write to the hon. Lady and put it right.

In an article by Patrick Wintour published recently, Cruddas describes a ‘modern anomie’, a breakdown between an individual and his or her community, and alludes to the challenge of institutions mediating globalisation. Cruddas also describes something which I have heard elsewhere, from Lord Stewart Wood, of a more ‘even’ creation of wealth, whatever this means about the even ‘distribution’ of wealth. One of the lasting legacies of the first global financial crisis is how some people have done extremely well, possibly due to their resilience in economic terms. For example, it has not been unusual for large corporate law firms to maintain a high standard of revenues, while high street law has come close to total implosion in some parts of the country. In a way, this reflects a shift from pooling resources in the State to a neoliberal free market model. The global financial crash did not see a widespread rejection of capitalism, although the Occupy movement did gather some momentum (especially locally here in St. Paul’s Cathedral). It produced glimpses of nostalgia for ‘the spirit of ’45”, but was used effectively by Conservative and libertarian political proponents are causing greater efficiencies. Indeed, Marks and Spencer laid off employees, in its bid to decrease the decrease in its profits, and this corporate restructuring was not unusual. A conservative and a libertarian have several things in common, the most important is the need for people to take care of themselves for the most part. Libertarians want to abolish as much government as they practically can. It is thought that the majority of libertarians are “minarchists” who favour stripping government of most of its accumulated power to meddle, leaving only the police and courts for law enforcement and a sharply reduced military for national defence. A minority are possibly card-carrying anarchists who believe that “limited government” is a delusion, and the free market can provide better law, order, and security than any goverment monopoly.

Essentially a libertarian would fund public services by privatising them. In this ‘brave new world’, insurance companies could use the free market to spread most of the risks we now “socialise” through government, and make a profit doing so. That of course would be the ideal for many in reducing the spend on the NHS, to produce a rock-bottom service with minimal cost for the masses. And to give them credit, the Health and Social Care Act was the biggest Act of parliament, that nobody voted for, to outsource the operations of the NHS to the private sector, which falls under the rubric of privatisation. Outsourcing is an arrangement in which one company provides services for another company that could also be or usually have been provided in-house. Outsourcing is a trend that is becoming more common in information technology and other industries for services that have usually been regarded as intrinsic to managing a business, or indeed the public sector. Many expected the election of the present government to herald a more determined approach to outsourcing public services to the private sector. Initially came the idea of the “big society”, with its emphasis on creating and using more social enterprises to deliver public services, but the backers for this new era of venture philanthropism were not particularly forthcoming. The PR of it, through Steve Hilton and colleagues, was disastrous, and even Lord Wei, one of its chief architects, left. No one in the UK likes the idea of domestic jobs moving overseas. But in recent years, the U.K. has accepted the outsourcing of tens of thousands of jobs, and many prominent corporate executives, politicians, and academics have argued that we have no choice, that with globalisation it is critical to tap the lower costs and unique skills of labour abroad to remain competitive. They argue that Government should stay out of the way and let markets determine where companies hire their employees. But is this debate ever held in public? No, there was always a problem with reconciling the need for cuts with an ideological thirst for cutting the State. Here in the UK, in 2010, the government indicated that it wanted to see new entrants into the outsourcing market, and the prime minister visited Bangalore, the heart of India’s IT and outsourcing industry, for high profile meetings with chief executives of companies such as TCS, Infosys, HCL and Wipro. Nobody ever bothers to ask the public what they think about outsourcing, but if Gillian Duffy’s interaction with Gordon Brown is anything to go by, or Nigel Farage’s baptism in the local elections has proved, the public is still resistant to a concept of ‘British jobs for foreign workers’. However, it is still possible that the general public are somewhat indifferent to screw-ups of outsourcing from corporates, in the same way they learn to cope with excessive salaries of CEOs in the FTSE100. The media have trained us to believe that unemployment rights do not matter, and this indeed has been a successful policy pursued by the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. People do not appear to blame the Government for making outsourcing decisions, for example despite the fact that the ATOS delivery of welfare benefits claims processing has been regarded by many as poor, the previous Labour government does not seem to be blamed much for the current fiasco, and the current fiasco has not become a major electoral issue yet.

And the list of screw-ups is substantial. G4S – the firm behind the Olympic security fiasco – has nowbeen selected to support the Police Service of Northern Ireland at the G8 Summit next month. Despite the company’s botched handling of the Olympics Games contract last summer, G4S has been chosen to supply 450 security staff for the event at Lough Erne, County Fermanagh The leaders of the world’s eight wealthiest countries are expected in Fermanagh on June 17 and 18. Meanwhile, medical assessments of benefit applicants at Atos Healthcare were designed to incorrectly assess claimants as being fit for work, according to an allegation of one of the company’s former senior doctors has claimed. Greg Wood, a GP who worked at the company as a senior adviser on mental health issues, said claimants were not assessed in an “even-handed way”, that evidence for claims was never put forward by the company for doctors to use, and that medical staff were told to change reports if they were too favourable to claimants. Elsewhere, Scotland’s hospitals were banned from contracting out cleaning and catering services to private firms as part of a new drive towards cutting the spread of deadly superbugs in the NHS. There were 6,430 cases of C. difficile infections in Scotland in one year recently, of which 597 proved fatal. The problem was highlighted by an outbreak of the infection earlier this year at the Vale of Leven hospital in Dunbartonshire which affected 55 people. The infection was identified as either the cause of, or a contributory factor in, the death of 18 patients.

Whatever our perception of the public perception, the impact on transparency and strong democracy merit consideration. As we outsource any public service, we appear to risk removing it from the checks and balances of good governance that we expect to have in place. Expensive corporate lawyers can easily outmanoeuvre under-resourced government departments, who often appear to be unaware of the consequences, and this of course is the nightmare scenario of the implementation of the section 75 NHS regulations. Even talking domestically, where contracts privilege commercial sensitivities over public rights, they can be used to exclude the provision of open data or to exempt the outsourcer from freedom of information requests. Talking globally, “competing in the global race” has become the buzzword for allowing UK companies to outsource to countries that do not have laws (or do not enforce laws) for environmental protection, worker safety, and/or child labour. However, all of this is to be expected from a society that we are told wants ‘less for more’, but then again we never have this debate. Are the major political parties afraid to talk to us about outsourcing? Yes, and it could be related to that other ‘elephant in the room’, about whether people would be willing to pay their taxes for a well-run National Health Service, where you would not be worried about your local A&E closing in the name of QUIPP (see this blogpost ). Either way, Jon Cruddas is right, I feel; the ‘modern anomie’ is the schism between the individual and the community, and maybe what Margaret Thatcher in fact meant was ‘There is no such thing as community’. If this means that Tony Blair feels that ‘it doesn’t matter who supplies your NHS services’, and we then get invasion of the corporates into the NHS, you can see where thinking like this ultimately ends up.

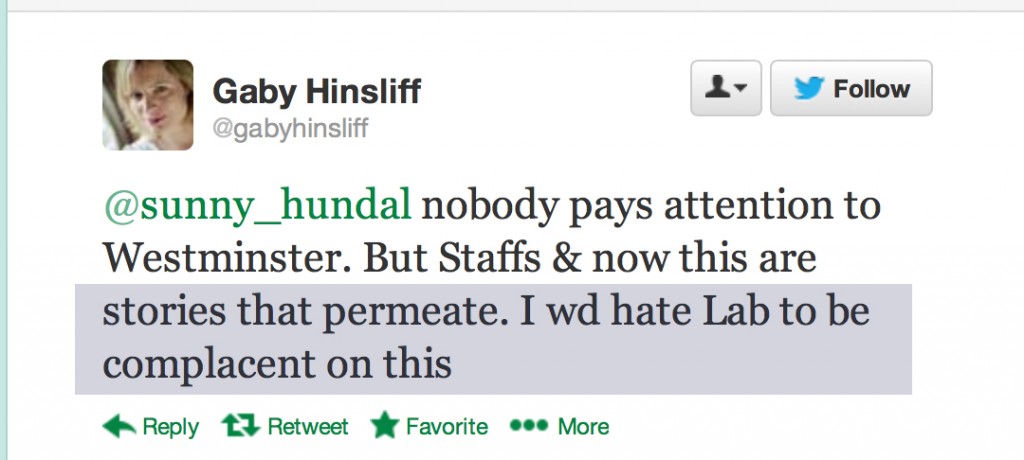

Politically, outsourcing vast amounts of the National Health Service is a big mistake. Take for example the scenario of what happens when something goes wrong. Will you get your money back? The lack of responsibility of the private sector shows how the NHS has to bail out the surgical mistakes of PIP breast implants. The State, evil though it is, does make a habit however of bailing out the private sector, as we all remember from the £860 bailout for the banking industry. It seems like a ‘cost saving’, but it clearly isn’t, in the same way that the private finance initiative has become a ‘cash cow’ for corporates. The essence of NHS policy is not to let the policy lunatics take over, in this case people with clearly vested interests having more impact on policy than professionals in the field. Part of the problem is that there is a lot more in common for Conservative and Labour policies, and indeed this is contributing to a growing sentiment that Labour is becoming complacent on the NHS (tweet by @gabyhinsliff):

Time will tell whether such fears will indeed materialise.

If I could predict the future of my health, would I change my behaviour?

A major issue in economics certainly is how individuals cope with information. Much information is uncertain, so one’s ability to make rational decisions based on irrational information is a fascinating one. Predicting the future may be viewed as best kept as the bastion of astrologers such as Mystic Meg, but the likelihood of future outcomes is clearly of interest in the insurance industry. These decisions are not only helpful for people at an individual basis, but also hopefully useful for planning, rather than predicting, what is best for the population at large in future.

Angelina Jolie did not have cancer, but, in fact, like many women with breast cancer mutations, she had the radical surgery to lower her risk. She, at the age of 37, has described her decision as “My Medical Choice,” in an op-ed in the New York Times. She carries the BRCA1 gene mutation, which gives her an 87% risk of developing breast cancer at some point in her life. The abnormal gene also increases her risk of getting ovarian cancer, a typically aggressive disease, by 50%. To counteract those odds, Jolie wrote that she decided to have both her breasts removed. In 2010, Australian scientists found that women with the BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations who chose to have preventive mastectomies did not develop breast cancer over the three-year follow-up. Since the genetic abnormalities increase the risk of ovarian cancer, women who had their ovaries and fallopian tubes removed also dramatically lowered their risk of developing ovarian or breast cancers. The ability of medicine to predict one day, with relative certainty, the likelihood to develop certain conditions is an intriguing way, and leaves the open the possibility of ‘personalised medicine’ on the basis of your own individual information. If you think the NHS is already overstretched, with A&E closures contributing to the ‘crisis’ in emergency health provision, then footing a bill for personalised medicine might be the ‘straw that breaks the camel’s back’. The idea that one day you can predict the likelihood of a person developing multiple sclerosis or Alzheimer’s Disease still intrigues neurologists.

This furthermore presents formidable challenges for the law. In recent years, governments have been embracing policies that ‘nudge’ citizens into making decisions that are better for their own health and welfare, including our own Government which has decided to ‘mutualise’ its own ‘Nudge Unit’. The European Commission has embraced this ‘libertarian paternalism’ in its review of the Tobacco Products Directive. Various people has recently explained that by introducing measures such as plain packaging and display bans, the European Union may be able to ‘nudge’ people into smoking less, whilst preserving their right to choose. After having relied on the assumption that governments can only change people’s behaviour through rules and regulations, policy makers seem ready to design polices that better reflect how people really behave. Inspired by “libertarian paternalism,” the nudge approach suggests that the goal of public policy should be to steer citizens towards making positive decisions as individuals and for society while preserving individual choice.

It’s likely that a ‘one glove fits all’ policy is not going to work. About a decade ago, I was surrounded in my day job by individuals with hepatic cirrhosis, requiring abdominal paracentesis to tap away fluid from their tummies. And yet being confronted with people yellow due to the build-up of bilirubin did not deter me one jot from being a card-carrying alcohol. I am not over seventy months in recovery from alcohol misuse, so this aspect of how people make decisions before being addicted intrigues me. I think that people genuinely in addiction ‘can’t say stop’, as they don’t have an off-switch; they lack insight, and are in denial, mostly, I feel from personal experience.

It’s also clear that there is a long-list of medical problems that cause someone to present to an A&E department aside from alcohol, such as a sore-throat, faint, dislocated shoulder, and so on. But alcohol is undeniably a big issue, so the question is a sobering one, pardon the pun. To what extent can we ‘nudge’ people out of alcohol-related illness? Commenting on the report out today from the College of Emergency Medicine, that highlights the pressures that Accident and Emergency (A&E) wards are under, Dr John Middleton, Vice President for Policy at the Faculty of Public Health, said:

“We quite rightly have high expectations of doctors and nurses working in emergency medicine, so it’s only fair that they get the support they need to do their jobs safely and well. One way to reduce the burden on Accident and Emergency (A&E) wards would be to tackle the reasons why people are admitted in the first place: in particular, alcohol. Given that drink related violence accounts for over one million A&E visits every year, we urgently need the government to be bold and introduce a minimum price per unit of alcohol. That would reduce the burden on overstretched hospitals and society as a whole.”

Nobody likes assessing risk, especially the consequences of an addict picking up/using again are potentially catastrophic even if in probability terms theoretically infinitesimally low. People who know about Taleb’s “Black Swan” work will know this well. And assessing harm has led others to be blasted in the public arena previously, for example Prof David Nutt who once compared the dangers of horse riding to the dangers presented by the major drugs of abuse. At a time when both the medical and legal professions at least think there should be an open debate about having ‘another look’ at the Misuse of Drugs Act (1971), hopefully a public can welcome a mature debate on this.

Even today, the news reports that introducing a law to force cyclists to wear helmets may not reduce the number of hospital admissions for cycling-related head injuries.Researchers said that while helmets reduce head injuries and should be encouraged, the decrease in hospital admissions in Canada, where the law is in place in some regions, seems to have been “minimal”. The authors examined data concerning all 66,000 cycling-related injuries in Canada between 1994 and 2008 – 30% of which were head injuries. Writing in the British Medical Journal, the authors noted a substantial fall in the rate of hospital admissions among young people, particularly in regions where helmet legislation was in place, but they said that the fall was not found to be statistically significant.

I suppose all political parties desire people with capacity to make decisions about their own lifestyle and healthcare, very much in keeping with the ‘no decision about me without me’ philosophy currently in vogue. If push came to shove, if I could predict the future of my health, would I fundamentally change my behaviour? Probably within reason, but the only thing which I am pretty certain about is having another alcoholic drink may lead to a pattern of behaviour that will ultimately kill me.

If I could predict the future of my health, would I change my behaviour?

A major issue in economics certainly is how individuals cope with information. Much information is uncertain, so one’s ability to make rational decisions based on irrational information is a fascinating one. Predicting the future may be viewed as best kept as the bastion of astrologers such as Mystic Meg, but the likelihood of future outcomes is clearly of interest in the insurance industry. These decisions are not only helpful for people at an individual basis, but also hopefully useful for planning, rather than predicting, what is best for the population at large in future.

Angelina Jolie did not have cancer, but, in fact, like many women with breast cancer mutations, she had the radical surgery to lower her risk. She, at the age of 37, has described her decision as “My Medical Choice,” in an op-ed in the New York Times. She carries the BRCA1 gene mutation, which gives her an 87% risk of developing breast cancer at some point in her life. The abnormal gene also increases her risk of getting ovarian cancer, a typically aggressive disease, by 50%. To counteract those odds, Jolie wrote that she decided to have both her breasts removed. In 2010, Australian scientists found that women with the BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations who chose to have preventive mastectomies did not develop breast cancer over the three-year follow-up. Since the genetic abnormalities increase the risk of ovarian cancer, women who had their ovaries and fallopian tubes removed also dramatically lowered their risk of developing ovarian or breast cancers. The ability of medicine to predict one day, with relative certainty, the likelihood to develop certain conditions is an intriguing way, and leaves the open the possibility of ‘personalised medicine’ on the basis of your own individual information. If you think the NHS is already overstretched, with A&E closures contributing to the ‘crisis’ in emergency health provision, then footing a bill for personalised medicine might be the ‘straw that breaks the camel’s back’. The idea that one day you can predict the likelihood of a person developing multiple sclerosis or Alzheimer’s Disease still intrigues neurologists.

This furthermore presents formidable challenges for the law. In recent years, governments have been embracing policies that ‘nudge’ citizens into making decisions that are better for their own health and welfare, including our own Government which has decided to ‘mutualise’ its own ‘Nudge Unit’. The European Commission has embraced this ‘libertarian paternalism’ in its review of the Tobacco Products Directive. Various people has recently explained that by introducing measures such as plain packaging and display bans, the European Union may be able to ‘nudge’ people into smoking less, whilst preserving their right to choose. After having relied on the assumption that governments can only change people’s behaviour through rules and regulations, policy makers seem ready to design polices that better reflect how people really behave. Inspired by “libertarian paternalism,” the nudge approach suggests that the goal of public policy should be to steer citizens towards making positive decisions as individuals and for society while preserving individual choice.

It’s likely that a ‘one glove fits all’ policy is not going to work. About a decade ago, I was surrounded in my day job by individuals with hepatic cirrhosis, requiring abdominal paracentesis to tap away fluid from their tummies. And yet being confronted with people yellow due to the build-up of bilirubin did not deter me one jot from being a card-carrying alcohol. I am not over seventy months in recovery from alcohol misuse, so this aspect of how people make decisions before being addicted intrigues me. I think that people genuinely in addiction ‘can’t say stop’, as they don’t have an off-switch; they lack insight, and are in denial, mostly, I feel from personal experience.

It’s also clear that there is a long-list of medical problems that cause someone to present to an A&E department aside from alcohol, such as a sore-throat, faint, dislocated shoulder, and so on. But alcohol is undeniably a big issue, so the question is a sobering one, pardon the pun. To what extent can we ‘nudge’ people out of alcohol-related illness? Commenting on the report out today from the College of Emergency Medicine, that highlights the pressures that Accident and Emergency (A&E) wards are under, Dr John Middleton, Vice President for Policy at the Faculty of Public Health, said:

“We quite rightly have high expectations of doctors and nurses working in emergency medicine, so it’s only fair that they get the support they need to do their jobs safely and well. One way to reduce the burden on Accident and Emergency (A&E) wards would be to tackle the reasons why people are admitted in the first place: in particular, alcohol. Given that drink related violence accounts for over one million A&E visits every year, we urgently need the government to be bold and introduce a minimum price per unit of alcohol. That would reduce the burden on overstretched hospitals and society as a whole.”

Nobody likes assessing risk, especially the consequences of an addict picking up/using again are potentially catastrophic even if in probability terms theoretically infinitesimally low. People who know about Taleb’s “Black Swan” work will know this well. And assessing harm has led others to be blasted in the public arena previously, for example Prof David Nutt who once compared the dangers of horse riding to the dangers presented by the major drugs of abuse. At a time when both the medical and legal professions at least think there should be an open debate about having ‘another look’ at the Misuse of Drugs Act (1971), hopefully a public can welcome a mature debate on this.

Even today, the news reports that introducing a law to force cyclists to wear helmets may not reduce the number of hospital admissions for cycling-related head injuries. Researchers said that while helmets reduce head injuries and should be encouraged, the decrease in hospital admissions in Canada, where the law is in place in some regions, seems to have been “minimal”. The authors examined data concerning all 66,000 cycling-related injuries in Canada between 1994 and 2008 – 30% of which were head injuries. Writing in the British Medical Journal, the authors noted a substantial fall in the rate of hospital admissions among young people, particularly in regions where helmet legislation was in place, but they said that the fall was not found to be statistically significant.

I suppose all political parties desire people with capacity to make decisions about their own lifestyle and healthcare, very much in keeping with the ‘no decision about me without me’ philosophy currently in vogue. If push came to shove, if I could predict the future of my health, would I fundamentally change my behaviour? Probably within reason, but the only thing which I am pretty certain about is having another alcoholic drink may lead to a pattern of behaviour that will ultimately kill me.