Home » Posts tagged 'research'

Tag Archives: research

“Stop using stigma to raise money for us”, says a leading advocate living well with dementia

Let me introduce you to Dr Richard Taylor, a member of the Dementia Alliance International living well with dementia, in case you’ve never heard of Richard.

“We shouldn’t be put on ice”, remarks Taylor.

“Or when we shouldn’t be put in a freezer, when we our caregivers go on holiday. We too should take a vacation from our caregivers.. enjoy the company of other people with dementia and enjoy their company.”

Dr Taylor had explained how there is a feeling of camaraderie when people living with dementia meet in the room. This is somewhat different from an approach of people without dementia being ‘friendly’ to people with dementia, assuming of course that you can identify reliably who the people with dementia are.

We are now more than half way though ‘Dementia Awareness Week’, from May 18 – 24 2014. Stigma, why society treats people with dementia as somehow ‘inferior’ and not worth mixing with, was a core part of Dr Taylor’s speech recently at the Alzheimer’s Disease International conference held this year in Puerto Rico.

He has ‘been going around for the last ten years, … talking to people living with dementia, and listening to them.”

That’s a common ‘complaint’ of people living with dementia: other people hear them, but they don’t listen.

“Stigma defines who we are.. not confined to the misinformed media, or the ‘dementia bigots’. Stigma is within all of us. When I heard my diagnosis, I cried for weeks… I’d never heard of dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, but it was the stigma inside me.”

Commenting a new vogue in dementia care, which indeed I have written about in my first book on living well with dementia, Taylor remarks: “We’ve now shifted to ‘person-centred care’. I think that’s a good idea. I always ask the caregiver who that person was centred was on previously. But I do that because I know I can a bit of a smart-arse”

“The stigma is in the very minds of people who treat us.”

“But you actually believe we are fading away… and we are not all there… it is not to our benefit.”

“The use of stigmas to raise awareness must stop right now.”

” Very little attention is paid to humanity of people living with dementia.. The use of stigma to raise awareness and political support must stop. We must stop commercials with old people.. which end with an appeal for funds. That reinforces the stigma. That comes out of focus groups with a bunch of people they want to focus on.”

“What would make you give money to our organisation? An older person or a younger person… We had a contest in the United States of who should represent “dementia”. The lady who won was 87-year old man staring into the abyss with a caregiver with a hand on her shoulder…”

“Telling everybody with dementia that they’re going to die is a half-truth. The other half without dementia are going to die too. Making it sounds as if people are going to die tomorrow scares the life out of people… scares the money out of people.”

But it seems even the facts about dying appear to have got mixed up in this jurisdiction. Take for example one representation of the Alzheimer’s Society successful Dementia Awareness Week ‘1 in 3 campaign’.

This was a tweet.

But the rub is 1 in 3 over 65 don’t develop dementia.

Approximately 1 in 20 over 65 have dementia.

It’s thought that by the age of 80 about one in six are affected, and one in three people in the UK will have dementia by the time they die.

There was a bit of a flurry of interest in this last year.

Neither “Dementia Friends” nor “Dementia Awareness Week” can be accused, by any stretch of the imagination, of ‘capitalising on people’s fears”.

And the discomfort by some felt by speaking with some sectors of the population is a theme worthy of debate by the main charities.

Take this for example contemporaneous campaign by Scope.

But back to Richard Taylor.

“How are you going to spend the rest of your lives? Worrying about how you’re going to die, or dying how you’re going to live?”

“I believe there is an ulterior motive.. to appeal to our fear of dying.”

“Stop using the fear of us dying to motivate people to donate to your organisations. It makes us mad and complicates our lives more than it needs to be.”

“The corruption of words to describe people who live with dementia and who live with us must stop.”

Dr Richard Taylor argues that the charities which have worked out how best to use manipulative language are the dementia charities.

“The very people who should be stopping corruption in language are the very ones involved in… “We’re going to cure dementia” What does that mean? Or will it be a vaccine where none of you get it and we all die, and so there’s no dementia any more?”

Taylor then argues you will not find ‘psychosocial research’, on how to improve the life of people with dementia.

Consistent with Taylor’s claim, this recent report on a ‘new strategy for dementia research’ does not mention even any research into living well with dementia.

“We are heading for more cures.. we’ve set the date for it wthout defining it. If we’re going to cure it by 2025, what will I see in 2018 to know we’re on track? .. It’s corrupt language.. None of the politicians will be around.. But people with dementia will be around to be disappointed.”

Taylor notes that every article rounds off with: “And now with further investigation, there’s a hope this might do this and this might do that.”

Except the politicians and charities have learnt how to play the system. These days, in the mission of raising awareness’, a Public Health and Alzheimer’s Society project, many articles focus on ‘Dementia Friends’, and people can decide at some later date whether they want to support the Alzheimer’s Society.

Articles such as this, or this, or this, or this, or this, or this, or this, or this, or this, or this, or this, or this, for example.

They could as a long shot decide to support Alzheimer’s BRACE, or Dementia UK. Dementia UK have been trying desperately hard to raise awareness of their specialist nursing scheme, called “Admiral Nurses“.

It all begs the question is the focus of the current Government to promote dementia, or to promote the Alzheimer’s Society?

Take this tweeting missive from Jeremy Hunt, the current Secretary of State for Health in the UK:

According to Taylor, “We need to start helping for the present.”

He is certainly not alone in his views. Here’s Janet Pitts, Co-Chair of the Dementia Alliance International, who has been diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia. Janet is also keen on ‘person centred services’, ‘is very proud of the work [we] have been doing since [our] inception in June 2013′, and is an advocate.

“I am an example of where life is taken away, but where life is given back… [I want us to] live well with dementia, advocate for people with dementia, reduce stigma in dementia.”

Who were the biggest winners and losers of the G8 dementia summit? My survey of 96 persons without dementia

Background

The G8 summit on dementia was much promoted ‘to put dementia on top of the world agenda’.

It is described in detail on the “Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge” website.

I went only last Monday to Glasgow to the SDCRN conference retrospective on the G8 dementia. It was a sort-of debrief for people in the research community about what we could perhaps come to expect. And what we’d come to expect, just in case any of us had thought we’d dreamt is was the idea of identifying dementia before it had happened or just beginning to happen and stopping it in its tracks then and there with drugs.

This is of course a laudable aim, but an agenda utterly driven by the pharmaceutical industry. My philosophy (not mine uniquely) “Living well in dementia” is called “non-pharmacological interventions” to denote a sense of inferiority under such a construct.

Aim

There has never been a media report on people’s views about the G8 dementia summit.

There has never been an analysis of the messaging of this summit in the scientific press, to my knowledge.

This study was conducted as a preliminary exploratory study into the language used in a random sample of 75 articles in the English language.

Methods

I completed a survey of reactions to the G8 dementia summit held last year in December 2013. I recruited people off my Twitter accounts @legalaware and @dementia_2014, and there were 96 respondents. Responses to individual items varied from 63 to 96.

I used ‘SurveyMonkey’ to carry out this survey. With ‘SurveyMonkey’, you cannot complete the survey more than once.

(I have also already collected 19 detailed questionnaire responses from Clydebank which I intend to write up for the Alzheimer Europe conference later this year, also in Glasgow. And also six people living with dementia also responded; and I’ll analyse these replies separately. I reminded myself by looking at the programme of the summit again what the key topics for discussion were – drugs, drug development and data sharing, with a sop to innovations and provision of high quality of information. It is perhaps staggering that there has been no detailed analysis of who benefited from the G8 dementia, but given the nature of this event, the media reportage and the events of my survey, this retrospectively is not at all surprising to me.)

Exclusions

Persons with dementia were directed to a different link (of the same survey.)

Results

The results encompass a number of issues about media coverage, the relative balance of cure vs care, and who benefited.

Media coverage

Overall, most people had not caught any of the news coverage on the TV (56%) or radio (55%). But most had caught the coverage on the internet, for example Facebook or Twitter (66%). 87% of people said they’d missed the live webinar. It was possible to answer my survey without having caught of any of the G8 seminar, however.

So what did people get out of it and what did they expect? Most people did not think the summit was a “game changer” (53% compared to 16%; with the rest saying ‘don’t know’), although the vast majority thought the subject matter was significant (82%) (n = 90).

Therefore, unsurprisingly, a majority considered the response against dementia to be an opportunity for policy experts to produce a meaningful solution (58%). However, it’s interesting that 24% said they didn’t know (with a n = 90 overall.)

In summary, they had high hopes but few thought it was a good use of a valuable opportunity to talk about dementia.

Many of us in the academic community had been struck in Glasgow at the sheer “terror” in the language used in referring to dementia. A large part of the media seemed to go for a remorseless ‘shock doctrine’ approach. Prof Richard Ashcroft, a medical law and bioethics expert from Queen Mary and Westfield College, University of London, wrote a very elegant piece about this, and his personal reaction, in the Guardian newspaper.

In terms of language, the respondents were consistent in not viewing the response against dementia as a “fight” (61%), a “war” (84%), a “battle” (72%) or an “epidemic” (70%) (n ranging from 83 to 86). 56% of people considered it unreasonable to speak of “turning the tide against dementia”. In terms of personal reactions, 82% considered themselves not to be “shocked” by dementia.

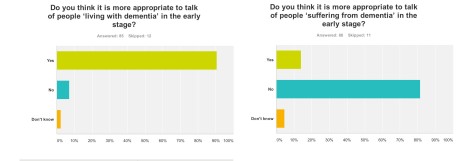

91% of people thought it was appropriate to talk of ‘living with dementia’ in the early stage (n = 85), but 82% of people did not think it was more appropriate to talk of people ‘suffering from dementia’ at this early stage (n = 86). In retrospect, I should’ve asked whether the appropriate phase was ‘living well with dementia’, so I suppose nearly 91% endorsing ‘living with dementia’ at all is not surprising. I have previously written about the use of the word “suffering”, as it is so commonly used in newspaper titles of articles of dementia here, though I readily concede it is a very real and complex issue.

The opportunity presented by the G8 dementia summit: cure vs care

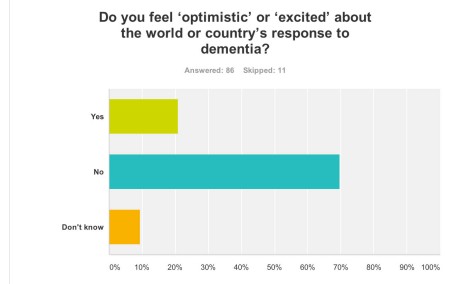

Despite all the media hype and extensive media coverage of the G8 dementia summit, 70% of people “did not feel excited about the world or country’s response to dementia” (n = 86).

But it is possibly hard to see what more could have been done.

The presentation by Pharma and politicians for their dementia agenda was extremely slick. This may be though due to a sense of politicisation of the dementia agenda, a point I will refer to below.

Early on in the meeting, World Health Organization Director-General Magaret Chan reminded the delegates – including politicians, campaigners, scientists and drug industry executives – how much ground there was to cover.

“In terms of a cure, or even a treatment that can modify the disease, we are empty-handed,” Chan said.

“In generations past, the world came together to take on the great killers. We stood against malaria, cancer, HIV and AIDS, and we should be just as resolute today,” Cameron said. “I want December 11, 2013, to go down as the day the global fight-back really started.”

It is therefore been of conceptual interest as to whether dementia can be considered in the same category as other conditions, some of which are obviously communicable. In my survey, people reported that that, before the summit, they would not have considered dementia comparable to HIV/AIDS (88%), cancer (70%), or polio (92%) (n = 86).

This is interesting, as a common meme perpetuated also by certain parliamentarians (who invariably spoke about Dementia Friends too) was that the same sort of crisis level in finding a cure for dementia should accompany what had happened for AIDS decades ago.

Biologically, the comparisons are weak, but it was argued that AIDS, like dementia now, suffered from the same level of stigma. Dementia, however, is an umbrella term encompassing about a hundred different conditions, so the term itself “a cure for dementia” is utterly moronic and meaningless.

Also in my survey, 67% of people reported that they did not feel more excited about the future of social care and support for people living with dementia (n = 85), and virtually the same proportion (66%) reported that they did not feel excited about the possibility of a ‘cure’ for dementia (defined as a medication which could stop or slow progression) (n = 85).

This reflects the reality of those people living in the present, perhaps caring for a close one with a moderate or severe dementia. It had been revealed that budget cuts have seen record numbers of dementia patients arriving in A&E during 2013. Regarding this, it was estimated that around 220,000 patients were treated in hospital as a result of cuts in social care budgets, which left them without the means to get care elsewhere.

It is known that the government has cut £1.8 billion from social care budgets, which is in addition to the pressure being applied to GP surgeries. In 2008 the number of dementia patients arriving in A&E was just over 133,000. The concern is that the Alzheimer’s Society, while working so close to deliver “Dementia Friends”, is not as effective in campaigning on this slaughter in social care as they might have done once upon a time. Currently, we now have the ridiculous spectacle of councils talking about dementia friendly communities while slashing dementia services in their community (as I discussed on the Our NHS platform recently).

Why Big Pharma should have felt the need to breathe life into the corpse of their industry for dementia is interesting, though, in itself. Pharma obviously is ready to fund molecular biology research, and less keen to fund high quality living well with dementia, and there is also concern that this agenda has pervasively extended to dementia charities where “corporate capture” is taking place. A massive theme of the G8 dementia summit was in fact ‘personalised medicine’. For example, there is growing evidence that while two patients may be classified as having the same disease, the genetic or molecular causes of their symptoms may be very different. This means that a treatment that works in one patient will prove ineffective in another. Nevertheless, it is argued the literature, public databases, and private companies have vast amounts of data that could be used to pave the way for a better classification of patients. According to my survey, despite ‘personalised medicine’ being a big theme of the summit, strikingly 66% felt that this was not adequately explained. There’s no doubt also that the Big Pharma have been rattled by their drugs coming ‘off patent’ as time progresses, such as donepezil recently. This has paved the way for generic competitors, though it is worth noting that certain people have only just given up on the myth that cholinesterase inhibitors, a class of anti-dementia drugs, reliably slowed the progression of Alzheimer’s disease in the majority of patients.

Who benefited?

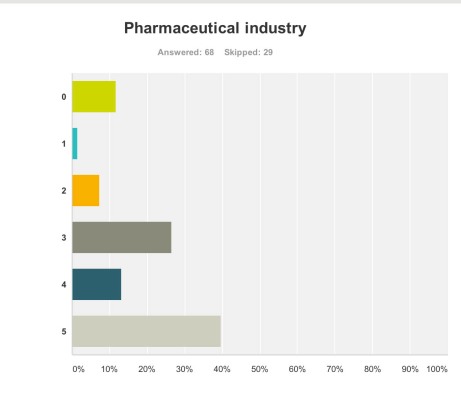

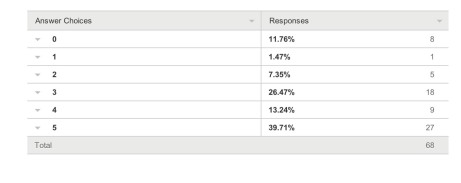

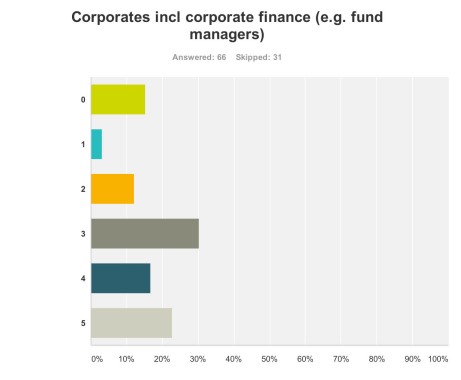

In terms of who ‘benefited’ from the G8 dementia summit, I asked respondents to rate answers from 0 (not at all) to 5 (completely).

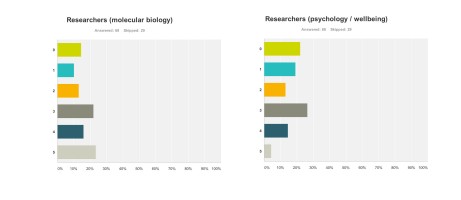

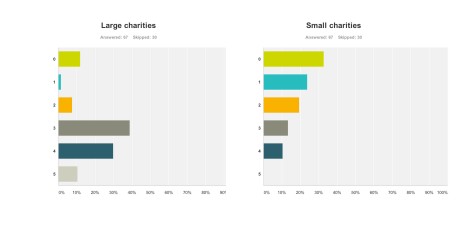

Research First of all, it doesn’t seem researchers themselves are “all in it together”. For example, these are the graphs for researchers (molecular biology) (n = 68) and researchers (wellbeing) (n = 68), with rather different profiles (with the public perceiving that researchers in molecular biology benefited more). This can only be accounted for by the fact there were many biochemical and neuropharmacological researchers in the media coverage, but no researchers in wellbeing.

Pharmaceutical industry But the survey clearly demonstrated that the pharmaceutical industry were perceived to be the big winners of the G8 dementia (n = 68).

Ministers are hoping a government-hosted summit on dementia research will help boost industry’s waning interest in the condition, and to some extent campaigners have only themselves to blame for pinning their hopes on this one summit.

The G8 Summit came amidst fears the push to find better treatments is petering out, and it is still uncertain how effective some drugs currently in Phase III trials might be, given their problems with side effects and finding themselves into the brain once delivered.

And the breakdown is as follows:

Charities The survey also revealed a troubling faultline in the ‘choice’ of those who wish to support dementia charities, and potential politicalisation of the dementia agenda. It has been particularly noteworthy that this recent initiative in English policy was branded “the Prime Minister Dementia Challenge”, and ubiquitously the Prime Minister was (correctly) given credit for devoting the G8 to this one topic.

A previous press release had read,

“Launched today by Prime Minister David Cameron, the scheme, which is led by the Alzheimer’s Society, people will be given free awareness sessions to help them understand dementia better and become Dementia Friends. The scheme aims to make everyday life better for people with dementia by changing the way people think, talk and act. The Alzheimer’s Society wants the Dementia Friends to have the know-how to make people with dementia feel understood and included in their community.. By 2015, 1 million people will become Dementia Friends. The £2.4 million programme is funded by the Social Fund and the Department of Health. The scheme has been launched in England today and the Alzheimer’s Society is hoping to extend it to the rest of the UK soon. Each Dementia Friend will be awarded a forget-me-not badge, to show that they know about dementia. The same forget-me-not symbol will also be used to recognise organisations and communities that are dementia friendly. The Alzheimer’s Society will release more details in the spring about what communities and organisations will need to do to be able to display it.”

Therefore, the perception had arisen amongst the vast majority of my survey respondents that large charities were big winners from the G8 dementia summit. This is perhaps unfair as there was not much representation from other big charities apart from the Alzheimer’s Society, for example Dementia UK or the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

I feel that this distorted public perception in the charity sector for dementia is extremely dangerous.

And this finding is reflected in the corresponding graph for ‘small charities’. Small charities were not represented at all in any media coverage, save for perhaps ambassadors of smaller charities there in a personal capacity at the Summit.

The numbers sampled for their views on large and small charities were both 67.

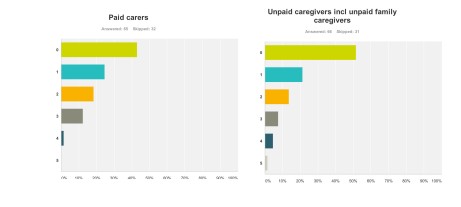

Paid carers and unpaid caregivers

The major elephant in the room, or maybe more aptly put an elephant who wasn’t invited to be in the room at all, was the carers’ community.

Only recently, for example, it’s been reported from Carers UK that half of the UK’s 6.5 million carers juggle work and care – and a rising number of carers are facing the challenge of combining work with supporting a loved one with dementia. The effects of caring for a person with moderate or severe dementia are known to be substantial, encompassing a number of different domains such as personal, financial and legal. It is also known that without the army of millions of unpaid family caregivers the system of care for dementia literally would collapse.

These are the graphs for paid (upper panel) and unpaid (lower panel) carers and caregivers (n = 65 and n = 66 respectively), with the most common response being “not at all benefiting”.

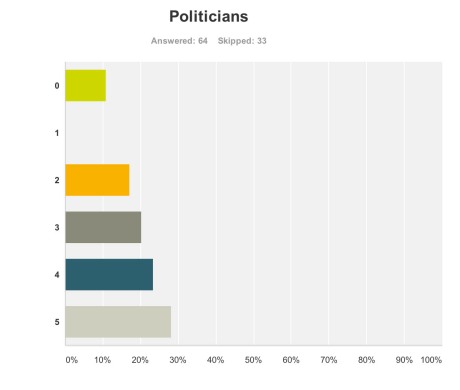

Politicians

But when asked if the politicians benefited, the result was very different.

Admittedly, few politicians were in attendance from the non-Government parties in England, and none from the main opposition party was given an opportunity to give a talk.

Both Jeremy Hunt and David Cameron gave talks. There is clearly not a lack of cross-party consensus on the importance of dementia, evidenced by the fact that the last English dementia strategy ‘Living well with dementia’ was initiated under the last government (Labour) in 2009.

The overall impression from 64 respondents to this question that politicians benefited, and some thought quite a lot.

Corporate finance A lot of discussion was about ‘investment’ for ‘innovation’ in drug research. Andrea Ponti is a highly influential man. He has been Global Co-head of Healthcare Investment Banking and Vice Chairman of Investment Banking In Europe of JPMorgan Chase & Co. since 2008. Mr. Ponti joined JPMorgan from Goldman Sachs, where he was a Partner and Co-head of European healthcare, consumer and retail investment banking, having founded the European healthcare team in 1997.

At the G8 dementia summit, Ponti advised that biotechnology and drug research can be a ‘risky’ investment for funders, rebalance of risk/reward needed. Ponti specifically made the point the rewards for investing in drug development had to be counterbalanced by the potential risks in data sharing (which are not insubstantial legally across jurisdictions because of privacy legislation).

Anyway, in summary, it was perhaps no surprise that my survey respondents felt that corporate finance were big winners of the summit (n = 65).

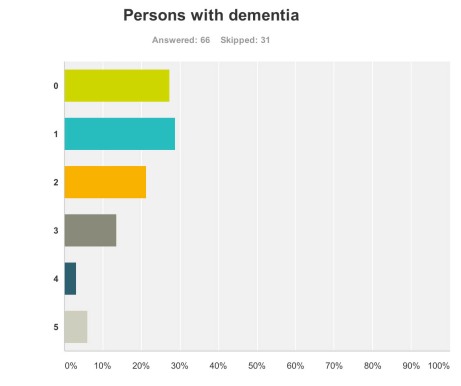

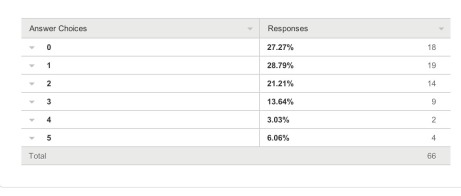

Persons with dementia And also for persons with dementia themselves?

One would have hoped that they would have been big winners according to my survey respondents, but the graph shows a totally different profile (with a minority of respondents rating that they benefited much.)

This is very sad.

66 answered this question.

The overall picture was this.

And the breakdown of results was this.

What will people do next?

Finally, it seemed as if the G8 Dementia Summit produced a ‘damp squib’ response with people in the majority neither more or less likely to donate to dementia charities (69%), donate to dementia care organisations (74%), get involved in befriending initiatives (72%), talk to a neighbour living with dementia or talk to a caregiver of a person living with dementia (58%), or get involved in dementia research (69%) (n varying from 73 to 78).

Limitations

Respondents were all in the UK, but the G8 dementia summit was clearly targeted in a multi-jurisdictional way.

It could be that there is huge bias in my sample, towards people more interested in care rather than Pharma. My follower list does include a significant number of people living with dementia or who have been involved in caring for people with dementia.

Conclusion

It would be interesting to know of any in-house reports from other organisations as to how they perceived they felt benefited from the G8 dementia, for example from patient representative groups, Big Pharma, carers and the medical profession. Pardon the pun, but the results taken cumulatively demonstrate a very unhealthy picture of the public’s perception in the dementia agenda in England, who calls the shots, and who benefits.

Given that this G8 dementia was to a large extent supposed to establish a multinational agenda until 2025, in parallel to the multinational nature of the response of the pharmaceutical industry, for those of us who wish to promote living well with dementia, it is clear some people are actually the problem not the solution.

This is incredibly sad for us to admit, but it’s important that we’re no longer in denial over it.

Public engagement with science must be two-way: that’s why persons with early dementia are so important

I spent some of this afternoon at the Wellcome Trust on Euston Road. Euston Road is of course home of the oldest profession, as well as the General Medical Council too.

I was invited to go there to discuss my plans to bring about a behavioural change in dementia-friendly communities. You see, for people with early dementia, say perhaps people with newly diagnosed dementia and full legal capacity, I feel we should be talking about communities led by people with early dementia.

The last few years for me as a person with two long term conditions, including physical disability, have really given me an urge to speak out on behalf of people who can become too easily trapped by being ‘medicalised’.

I have had endless reports of persons with dementia who have received no details about their dementia from the medical profession on initial diagnosis, and at worst simply given an information pack.

This is not good enough.

How we all make decisions is a fundamental part of life. When a person loses the ability to make decisions, it can be a defining moment – loss of capacity triggers certain legal pathways. Whilst the state of the law on capacity is quite good (through the Mental Capacity Act 2005), it is likely that further welcome refinements in the law on capacity will be seen through the current consultation on the said act.

I have been thinking about applying for a big grant to fund activities in allowing a discussion of decision-making in people with early diagnosis, the science of decisions, and what one might do to influence your decision-making (such as not following the herd).

I’ve also felt that quite substantial amounts of money get pumped into Ivory Tower laboratories on decision-making, but scientists would benefit from learning from people with early dementia regarding what they should research next, as much as informing people with early dementia what the latest findings in decisions neuroscience are.

Also, the medical profession and others are notoriously bad at asking people with dementia what they think about their own decision making. This ‘self reflection’ literature is woefully small, and this gap I feel should be remedied.

I simply don’t think that what scientific funding bodies do has necessarily to interfere with the NHS. I think a motivation to explain and discuss the science of decisions to stimulate a public debate is separable from what the NHS does to encourage people to live well with dementia. This debate can not influence what scientists do, but can influence what lawyers and parliament wish to do about capacity in dementia.

Persons can be encouraged to live well with dementia, and when they become ill they become patients of the NHS. Living well with dementia is for me a philosophy, not a healthcare target. If I can do something to promote my philosophy and help people, I will have achieved where many people in their traditional rôles as medical doctors have gloriously failed as regards dementia.

I intend to promote the need of high quality wellbeing research at the SDCRN 4th Annual Conference on dementia in Glasgow today

This is the programme for today which I’m looking to enormously today.

I will be promoting heavily the cause of living well with dementia, to swing the pendulum away from pumping all the money into clinical trials into drug trials for medications which thus far have had nasty side effects.

In keeping with this, I have been given kind permission to give out my G8 Dementia Summit questionnaire to look at delegates’ perception of what this conference was actually about.

We need also not to lose sight of the current persons with dementia, to ensure that they have good outcomes in the wellbeing.

This can be achieved through proper design of care environments, access to innovations including assistive technology, meaningful communities and networks for people with dementia to be part of and to lead in, and proper access to advocacy support services and information which empower choice and control.

There’s a lot to do here – and we need to have high quality research into all of this arm of research too.

Coming back home to Scotland is like travelling back in time for me.

I was born in Glasgow on June 18th 1974, and my lasting memory of leaving Glasgow for London 37 years ago was how relatively unfriendly Londoners were in comparison.

Of course the train journey through the beautiful England-Scottish border countryside brought it back to me. There’s a lot to be said for getting out of London. It’s an honour to be here back in Scotland.

I had absolutely no idea I would have such a warm welcome here in Scotland. Still feeling incredibly emotional I’m here at all in Glasgow.

— shibley (@legalaware) March 24, 2014

@legalaware @tommyNtour @theRSAorg @PeterDLROW Enjoy the #SDCRN conference tomorrow all. I will be watching for tweets

— SJ (@YeWeeStoater) March 23, 2014

@legalaware @YeWeeStoater @RealTaniceJudge Peters & Lee welcome home you’ve been gone 2 long come in& close the door http://t.co/LHQvVMprcc

— youcanmakedifference (@tommyNtour) March 23, 2014

Burst into tears on arriving home in #Glasgow just now @tommyNtour @YeWeeStoater @realtanicejudge pic.twitter.com/UG64xKc4GK

— shibley (@legalaware) March 23, 2014

@legalaware Lucky you. You will get a warm Scots welcome I’m sure!

— alison eaton (@doctorsnoddy) March 23, 2014

Penultimate stop in Carlisle. In my 40th year returning to #scotland at long last. pic.twitter.com/og6OAGSc66

— shibley (@legalaware) March 23, 2014

@legalaware @BarbaraACannon @Johnrashton47 Glad there are blues skies to greet you Shibley! Have a great conference!

— Dr ShirleyLockeridge (@DrShirleyLock) March 23, 2014

@legalaware welcome up north! Anything exciting?

— #hellomynameis Paul (@pauljebb1) March 23, 2014

At Penrith – nearly back home in Scotland @YeWeeStoater @tommyNtour pic.twitter.com/ZLpchE3YxE

— shibley (@legalaware) March 23, 2014

@DrShirleyLock @BarbaraACannon @Johnrashton47 now waving (not drowning) at Lancaster pic.twitter.com/ubphOxFF4W

— shibley (@legalaware) March 23, 2014

Welcome to Preston! pic.twitter.com/LQ1i67Dgx4

— shibley (@legalaware) March 23, 2014

Warrington still England surely? 3 hrs til Glasgow @BendyGirl pic.twitter.com/XFhyOKw5Ku

— shibley (@legalaware) March 23, 2014

Surprise surprise this Virgin train left on time from Euston at 1228 pm @SocialistHealth

— shibley (@legalaware) March 23, 2014

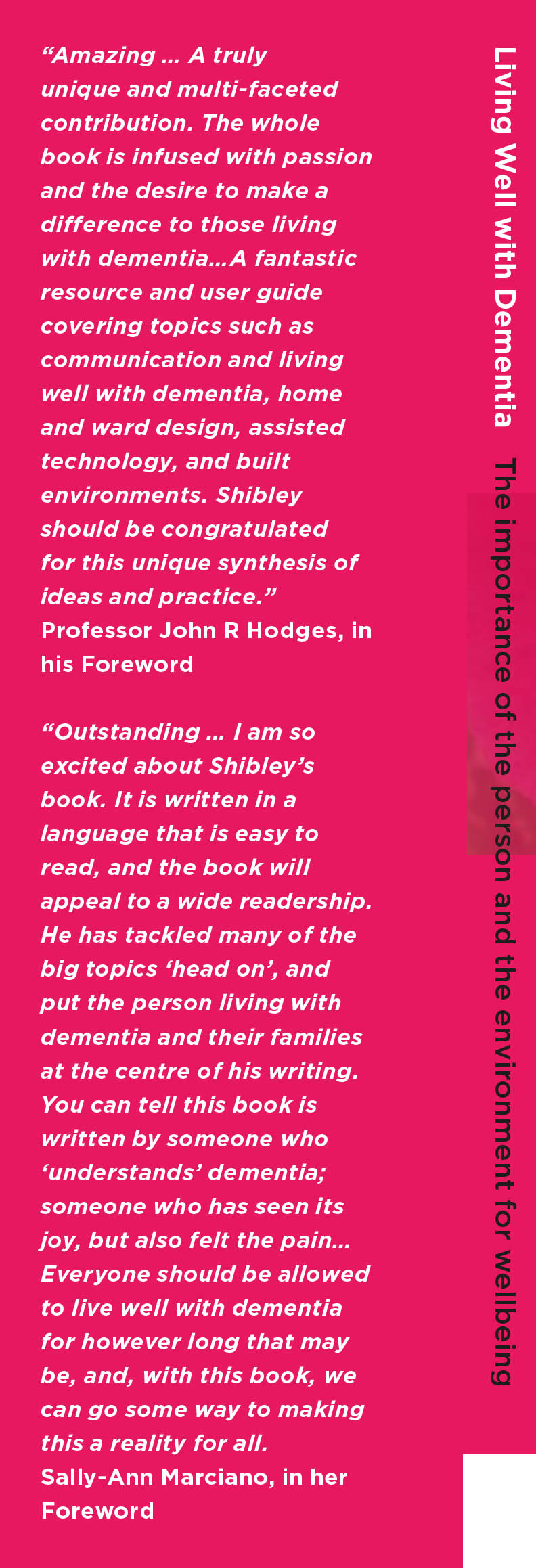

My book ‘Living well with dementia’ is here.

Contents

Dedication • Acknowledgements • Foreword by Professor John Hodges • Foreword by Sally Ann Marciano • Foreword by Professor Facundo Manes • Introduction • What is ‘living well with dementia’? • Measuring living well with dementia • Socio-economic arguments for promoting living well with dementia • A public health perspective on living well in dementia, and the debate over screening • The relevance of the person for living well with dementia • Leisure activities and living well with dementia • Maintaining wellbeing in end-of-life care for living well with dementia • Living well with specific types of dementia: a cognitive neurology perspective • General activities which encourage wellbeing • Decision-making, capacity and advocacy in living well with dementia • Communication and living well with dementia • Home and ward design to promote living well with dementia • Assistive technology and living well with dementia • Ambient-assisted living well with dementia • The importance of built environments for living well with dementia • Dementia-friendly communities and living well with dementia • Conclusion

Reviews

Amazing … A truly unique and multi-faceted contribution. The whole book is infused with passion and the desire to make a difference to those living with dementia…A fantastic resource and user guide covering topics such as communication and living well with dementia, home and ward design, assisted technology, and built environments. Shibley should be congratulated for this unique synthesis of ideas and practice.’

Professor John R Hodges, in his Foreword

‘Outstanding…I am so excited about Shibley’s book. It is written in a language that is easy to read, and the book will appeal to a wide readership. He has tackled many of the big topics ‘head on’, and put the person living with dementia and their families at the centre of his writing. You can tell this book is written by someone who ‘understands’ dementia; someone who has seen its joy, but also felt the pain…Everyone should be allowed to live well with dementia for however long that may be, and, with this book, we can go some way to making this a reality for all.’ –Sally-Ann Marciano, in her Foreword

An analysis of 75 English language web articles on the G8 dementia summit

Background

Experience has suggested that academic scientists can be as ‘guilty’ as the popular press in generating a ‘moral panic’ causing mass anxiety and hysteria. Take for example the media reporting of the new variant Creuztfeld-Jacob disease, a very rare yet important cause of dementia (Fitzpatrick, 1996).

How dementia is represented in the media is a good surrogate market of how the issue can be represented in certain segments of the culture of a society (Zeilig, 2014).

According to George, Whitehouse and Ballenger (2011), the concept of dementia, a term which they attribute to Celsus in the first century A.D. — has long carried “social implications for those so diagnosed and has been associated with reduced civilian and legal competence, as well as with entitlement to support and protection.

A range of emotionally charged metaphors about dementia pervades the popular imagination, and these are found in newspaper accounts, political speeches, and in both documentary and feature films. The ‘G8 dementia’ summit allowed many of these recurrent motifs to resurface unchallenged.

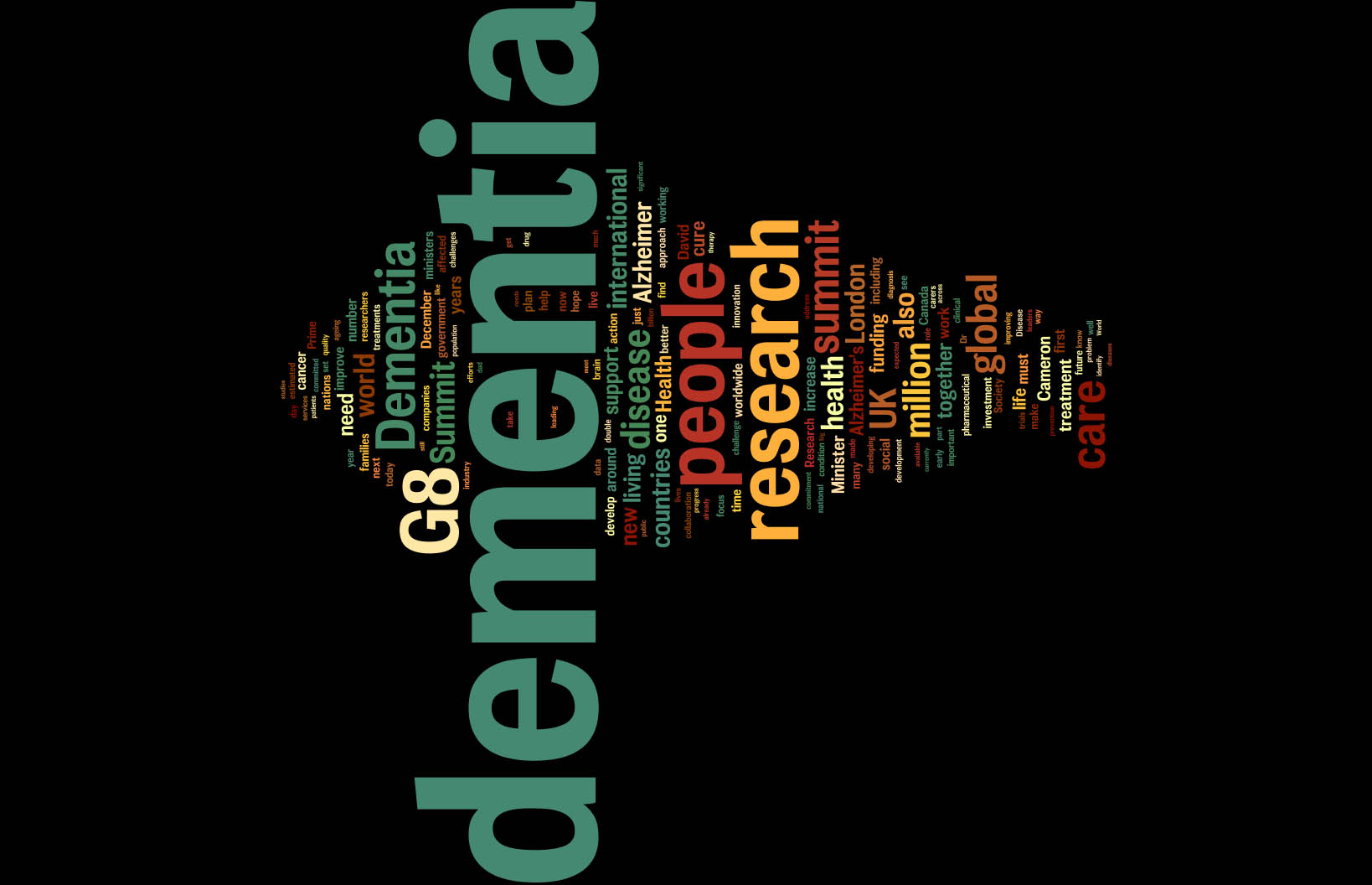

I’ve been intrigued how the G8 Dementia Summit was covered in the English-speaking media on the web. So I did a Google search for “G8 dementia”, on the UK Google site. It only came up with languages in English article, and I included the top 75 search results.

I excluded some search results. I excluded webpages consisting of only videos. Flickr photos or Pinterest boards. I decided to exclude articles less than 100 words long.

Aim

The aim of this piece of work was to complete a preliminary exploration of how the #G8dementia summit was reported on the internet in the English language.

The literature in this field is very small, and no study to my knowledge has ever been undertaken for the actual reporting of the G8 dementia summit which was unprecedented.

Methods

For the text analysis, done online using this tool, I excluded the author names, titles, location of authorship of the article (e.g. London). also excluded the endings, invariably, “Read more” “You may also like”, “You can read more about” and list of other ‘links’ to look at. I excluded duplicates. Finally, one article which was largely a compilation of tweets was excluded.

Results

Unsurprisingly, the word “dementia” featured 955 times, but encouragingly “people” featured 280 times. I found this quite gratifying as I have just published a book on the rôle of the person and the environment for living well with dementia – though the vast majority of articles did not have wellbeing as their main thrust.

I think the problem in English policy is revealed in the finding that “research” appears 334 times, and yet “wellbeing” is there fewer than eight times. The facts that “data” is used thirty times, with “collaboration” 28 times, hint at the overall drive towards data sharing for the development of cross-country trials and personalised medicine.

There seems to be a greater need for “funding” somewhere, a word used 66 times. There’s clearly an “international” focus, a word used 103 times.

The word “carers” was only used thirty times – a bit of a knee in the groin for the caring community?

The term “social care” is used 14 times across the 75 articles, but this is dwarfed by the use of the term “innovation” used 37 times. “Innovation” is of course a key meme of Big Pharma, as demonstrated by this infographic by Eli Lilly, a prominent company in dementia neuropharmacology.

The ideological bias towards the medical model for dementia is reflected in the frequency of the word “disease” or “diseases”, totalling 203; “treatment” or “treatments”, totalling 91; and “cure” or “cures”, totalling 72.

There’s clearly a bias towards Alzheimer’s disease, in that “Alzheimer” was used 145 times, with the word “vascular” used only six times. Strikingly, no other forms of dementia were mentioned. There are probably about a hundred known forms of diagnoses comprising the dementias, including some very common ones such as “frontotemporal” or “diffuse Lewy Body”.

Various authors, including Kate Swaffer who lives with a dementia herself, have often remarked on this bias known in the literature as “Alzheimerisation” (Swaffer, 2012).

“Cameron” is mentioned 60 times, and “Hunt” is mentioned 24 times. “Hughes”, as in Jeremy Hughes, CEO of the Alzheimer’s Society, is only mentioned 5 times.

It’s also interesting to see which other conditions are mentioned alongside dementia in these 75 articles. Only three were, in fact: these are “cancer” (45 times), HIV (25 times) and AIDS (29 times); treating HIV and AIDS as distinct, which is of course is not necessary to do, and there may have been no intention on the part of the journalists to use these words specifically in their narratives.

Thankfully, the usual dramatic terms were not used often.

“Timebomb” was only twice – once by the BBC

“It also called on the World Health Organization to identify dementia as “an increasing threat to global health” and to help countries adapt to the dementia timebomb.

[http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-25318194]

and then by a blog for the “Humanitarian Centre:

“Dementia has been branded a ‘timebomb’, as ageing populations will exacerbate the problems and costs associated with dementia.”

[http://www.humanitariancentre.org/2014/01/tackling-dementia-the-g8-dementia-summit-2]

The terms “bomb” or “bombs” were only used four times, and encouraging one of these was complaining about in a passage complaining about military metaphors.

“To make matters worse people living with dementia were exposed to scaremongering rhetoric. We already know that people living with dementia are directly affected by stereotypes and negative attitudes to dementia. The widespread use of military style metaphors – time bombs, battles, victims and fights in addition to media promotion of the term ‘suffering from dementia’ combine to increase fear of the disease for those living with it. This fear exacerbates the isolation and exclusion that people with dementia often feel following diagnosis.”

[http://www.centreforwelfarereform.org/library/by-date/g8-dementia-summit.html]

The dementia “time bomb” crops up frequently in U.K. broadsheets (Furness, 2012) and tabloids. Time bombs are devices that could go off at any time; their most common use has been in politically motivated terrorism. The association of dementia with terrorist tactics is fascinating, invoking the sense of a threat

The only use of the word “tide” was in a direct quotation from a speech by Jeremy Hunt, current Secretary of State for Health:

“We have turned the global tide in the battle against AIDS. Now we need to do it again. We will bankrupt our healthcare systems if we don’t,” he said.”

[http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/12/11/us-dementia-g-idUSBRE9BA0HE20131211]

The danger of flooding has long been associated with dementia. A 1982 U.K. report was entitled: “The rising tide: Developing services for mental illness in old age” (Arie and Jolley, 1983).

Note Hunt’s ‘wordie’ contains ‘heartache’, ‘threats’, ‘battle’, ‘dreading’, ‘stigma’ and ‘fight’, but also includes ‘diagnosis’, ‘people’ and ‘research’.

It is indeed fascinating the on-running theme of promoting dementia research in the absence of a context of wellbeing.

David Cameron’s ‘Wordie’ is quite tame.

But the consequences for this media messaging are potentially quite profound.

Limitations

There is a sample bias introduced with how Google orders its ranking.

Page ranking is not only calculated on the basis of traffic, but also in terms of degree of linkage with other websites.

It is possible that higher ranking articles, particularly online versions of newspaper articles, have a common root such as the Press Association, leading to a lack of independence amongst authors in their coverage of the Summit.

Conclusion

Whitehouse concludes a recent abstract as follows:

“Creating a more optimistic future will depend less on genetic and reductionist approaches and more on environmental and intergenerative approaches that will aid in recalibrating the study of AD from an almost exclusive focus on biochemical, molecular and genetic aspects to better encompass ‘‘real world’’ ecological and psychosocial models of health.”

Encouragingly though the frequency of words such as ‘timebomb’ and ‘flood’ were not as much as one might have feared, from the (albeit small) literature in this field.

If you assume that the 75 articles form a representative cohort of copy on the G8 dementia summit, the picture presented has a clear emphasis on a magic pharmacological bullet for dementia. The copy represents not a balanced debate, on behalf of all stakeholders, but reads like a business case to invest more in neuropharmacological-based research into dementia.

References

Arie, T., & Jolley, D. (1983). The rising tide. British Medical Journal, 286, 325–326.

Fitzpatrick, M. (1996) Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and bovine spongiform encephalopathy, BMJ, 312, 1037.3.

George, D.R., Whitehouse, P.J., Ballenger, J. (2011) The evolving classification of dementia: placing the DSM-V in a meaningful historical and cultural context and pondering the future of “Alzheimer’s”, Cult Med Psychiatry. 2011 Sep;35(3):417-35.

Furness, H. (2012, March 7). Dementia is ‘next global health time bomb.’ The Telegraph. Retrieved from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/health/healthnews/9127801/Dementia-is-next-global-health-time-bomb.html

Swaffer, K. (2012) Dementia, denial, old age and dying, blogpost here.

Whitehouse, P.J. (2014) The end of Alzheimer’s disease-From biochemical pharmacology to ecopsychosociology: A personal perspective. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014 Apr 15;88(4):677-681. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.11.017.

Zeilig H. (2014) Dementia as a cultural metaphor, Gerontologist, 54(2), pp. 258-67.

Why I wrote ‘Living well with dementia’

“Living well with dementia: the importance of the person and the environment for wellbeing” is my book to be published in the UK on January 14th 2014. I have written it on my own, but I have drawn on the published work a number of Professors working in the field of dementia have sent me. I hope the advantage of having an overview of their research programmes has been to put together with one voice where exactly this approach might be heading using the most contemporary published papers. I am enormously grateful that these busy Professors were able to supply me with their recent papers.

I was asked by my publishers to provide pointers about what a “marketing strategy” for this book might be. I can honestly say that, having given considerable time to thinking about this issue, I have no intention of pursuing a conventional promotion of my book. I don’t intend to do nothing, but I can confidently say that this book will be widely read. I have no intention of flogging it to commissioners, who will have their own understanding of what health or wellbeing is in the modern construct of NHS England’s policy.

I do, however, have every intention of addressing what I think is a major shortfall in the medical profession in their approach to dementia. Their emphasis has been, where done well, the exact diagnosis of dementia through an accurate history and examination of a patient, with appropriate investigations to boot (such as a CT scan, MRI, lumbar puncture, EEG or cognitive psychology). The combined efforts of Big Pharma and medics have produced limited medications for the symptomatic treatment of memory and attention in some dementias, but it would simply be a lie to say that they have a big effect in the majority of patients, or that they reverse the underlying the disease process consistently and robustly.

But that’s the medical model, and certainly the ambition for a ‘cure’ is a laudable one. I found the recent G8 dementia summit inspiring, but a bit of a distraction from providing properly funded solutions for people currently living with one of the hundreds of dementias. Many of us in the academic community have had healthy collaborations for some time; see for example one of the Forewords to my book by Prof Facundo Manes, Chair of Research of the World Federation of Neurology (Dementia and aphasia). To say it was a ‘front’ for Big Pharma would be unnecessarily aggressive, but it has been openly admitted in the media that a purpose of the summit was to assist ‘an ailing industry’.

I think to emphasise what might be done for future patients of dementia would be to fail to maximise the living of people with dementia NOW. By this, I mean a correct and timely diagnosis of an individual, the suggestion of appropriate assistive technologies and innovations, appropriate leisure activities, and the proper design of a positive environment (whether that be a ward, a house or external environment).

My book is strongly footed in current research, but I openly admit that research does not have all the answers. I should like there to be a strong emphasis also in non-pharmacological approaches, such as the benefits of life story and reminiscence, art or dancing. Lack of current research certainly does not make these approaches automatically invalid, particularly when you consider the real reports of people with dementia who have reported benefit.

The main reason is that I do not wish to organise attendance in a series of workshops or conferences about dementia is that I do not wish to be perceived as selling a book. I am more than happy to talk about the work if anyone should so desire. A number of my friends are very well-known newspaper journalists, and I deliberately have not approached any of them as I consider this might be taking advantage of my friendship. I haven’t approached dementia campaigners, or other dementia charities, as I don’t wish to get involved in some sort of competition for other people’s attention. I haven’t sought the ‘celebrity backing’ of some senior practitioners in dementia, although Prof John Hodges (a world expert particularly in the frontotemporal dementias) kindly wrote one of my Forewords. If people wish to discuss the issues in a collaborative manner to take English policy further, I’d be delighted.

At the centre of this book is what an individual with dementia CAN do rather what they cannot do. If you’re looking for a cogent report into the medical deficits of people with dementia, you’ll be sorely disappointed. I spent about 10 years of medical training at undergraduate and postgraduate levels, without having heard of personhood or Tom Kitwood’s work once. I think this a travesty. As a person who is physically disabled himself, the need to understand the whole person is of massive personal significance to me. I think that, beyond doubt, future training of anyone in the caring professions, including medicine, will have to start with understanding the whole person, rather than seeing a patient with a series of problems to be cured or symptomatically addressed.

No academic, practitioner, or charity can have a monopoly of ideas, which is why I hope my book will be sincerely treated with an open mind. People have different motivations for why they get involved in dementia; for example, a corporate wishing to be part of a ‘dementia friendly community’ through a charity might have a different guiding principle to an academic at a University wishing to research from scratch some of the fundamental principles of a dementia friendly community. Despite all the “big players”, nobody can match up to THAT individual who happens to be living with dementia; that person is entitled to the utmost dignity and respect, as brilliantly expressed by Sally Marciano in her powerful Foreword.

I am hoping very much to meet up with some personal friends that I’ve met in the #dementiachallengers community on January 18th 2014, and this is as close as I’ll get to the book launch. But I hope you will find the book readable. I don’t feel that there’s any other book currently available which bridges these two totemic topics (dementia and wellbeing); but I hope there are other good reasons for reading it!

Related articles

- Need for Dementia Caregivers Grows as Boomers Age (abcnews.go.com)

- A cure for dementia could be found within twelve years, David Cameron has said (telegraph.co.uk)

- Simple Steps Could Keep People With Dementia at Home Longer: Study (nackpets.wordpress.com)

Does it matter the public was completely misled about the real motives of the G8 dementia summit?

You can argue that the general public were not in fact misled over anything.

The Department of Health had a live stream for the entire day, and the communique and declaration were made available at the end of the day.

It can be argued that the scale of the issue of prevalence of cases of dementia is significant. The media, however, did such a fantastic job in using words such as ‘time bomb’ in scaring the public across all media outlets that Prof Alistair Burns was put in a difficult position as to why dementia policy had appeared to ‘fail’. Burns explained with immaculate civility that the prevalence of dementia had appeared to be falling in recent years to a quiet adversarial but polite Emily Maitlis.

The spectacle of the G8 dementia was though a deception of the highest order. The emotions you were undoubtedly supposed to feel were that it was your fault that you hadn’t realised that dementia was a significant public policy issue.

One lie led to another unfortunately. There are at least two hundred different types of dementia. Some are completely reversible. Some are easier to treat than others. Therefore it was completely meaningless to talk of a single cure for dementia by 2025. Some senior medic should have stopped these health ministers including Jeremy Hunt making a fool of themselves.

They did not even aspire to promote good care primarily; they did not pledge monies in this direction; they gave a firm commitment to disseminate examples of good care.

There is no doubt that much more can be done in basic research to do with how Alzheimer’s disease comes about, and to examine why after fifteen years there is no consistent narrative about their lack of the slowing of disease progression.

What is though to me still unfathomable is why it has not been reported what this ‘open data’ agenda is about. It is about the sharing of clinical “big data”, including DNA genomics, across jurisdictions for the development of personalised medicine.

Innovations for wellbeing might be profitable, but nothing compared to this new project of Big Pharma. And there isn’t a single thing about it in the media. How did the G8 choreograph with such synchrony such a united response all of a sudden? It’s because it’s known that big data and personalised medicine are “the next big thing” in profitability for Big Data. And crucially the other approaches have failed.

You cannot help but feel physically sick at the outcome of this unique opportunity. It’s not accidental there was hardly a discussion of the caring shortfalls in any jurisdiction. The worst thing about this deception is that the public don’t even know that they have been deceived. As long as they donate money voluntarily for ‘research’ and/or participate in ‘dementia friends’, and so long charities can deliver in return some people contributing to the ‘big data’ sample, everyone’s a winner.

The sheer terror helps.

Everyone’s a winner.

Except the person with dementia.

Dementia: where is the policy cart now?

The most ‘perfect’ scenario for dementia screening would be to identify dementia in a group of individuals who have absolutely no symptoms might have subtle changes on their volumetric MRI scans, or might have weird protein fragments in their cerebrospinal fluid through an invasive lumbar culture; and then come up with a reliable way to stop it in its tracks The cost, practicality and science behind this prohibit this approach.

There are well defined criteria for screening, such as the “Wilson Jungner criteria“. Prof Carol Brayne from the University of Cambridge has warned against the perils of backdoor screening of dementia, and the need for evidence-based policy, publicly in an article in the British Medical Journal:

“As a group of clinical and applied researchers we urge governments, charities, the academic community and others to be more coordinated in order to put the policy cart after the research horse. Dementia screening should neither be recommended nor routinely implemented unless and until there is robust evidence to support it. The UK can play a unique role in providing the evidence base to inform the ageing world in this area, whilst making a positive difference to the lives of individuals and their families in the future.”

However, a problem has arisen in how aggressively to find new cases of dementia in primary care, and a lack of acknowledgement by some that incentivising dementia diagnosis might possibly have an untoward effect of misdiagnosing (and indeed mislabelling) some individuals, who do not have dementia, with dementia. Unfortunately there are market forces at work here, but the primary consideration must be the professional judgment of clinicians.

Diagnosing dementia

There is no single test for dementia.

A diagnosis of dementia can only be confirmed post mortem, but there are ‘tests’ in vivo which can be strongly indicative of a specific dementia diagnosis (such as brain biopsy for Variant Creutzfeld-Jacob disease or cerebral vasculitis), or specific genetic mutations on a blood test (such as for relatively rare forms of the dementia of the Alzheimer type).

Memory vs non-memory functions in CANTAB

CANTABmobile is a new touchscreen test for identifying memory impairment, being described as a ‘rapid memory test’. The hope is that memory deficits might be spotted quickly in persons attending the National Health Service, and this is indeed a worthy cause potentially. In the rush to try to diagnose dementia quickly (and I have explained above the problem with the term “diagnose dementia”), it is easy to conflate dementia and memory problems. However, I demonstrated myself in a paper in Brain in 1999 using one of the CANTAB tests that patients with behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) were selectively impaired on tests sensitive to prefrontal lobe function involving cognitive flexibility and decision-making. I demonstrated further in a paper in the European Journal of Neuroscience in 2003 that such bvFTD patients were unimpaired on the CANTAB paired associates learning test.

bvFTD is significant as it is a prevalent form of dementia in individuals below the age of 60. The description given by Prof John Hodges in the current Oxford Textbook of Medicine chapter on dementia is here. Indeed, this chapter cites my Brain paper:

“Patients present with insidiously progressive changes in personality and behaviour that refl ect the early locus of pathology in orbital and medial parts of the frontal lobes. There is often impaired judgement, an indifference to domestic and professional responsibilities, and a lack of initiation and apathy. Social skills deteriorate and there can be socially inappropriate behaviour, fatuousness, jocularity, abnormal sexual behaviour with disinhibition, or theft. Many patients are restless with an obsessive–compulsive and ritualized pattern of behaviour, such as pacing or hoarding. Emotional labiality and mood swings are seen, but other psychiatric phenomena such as delusions and hallucinations are rare. Patients become rigid and stereotyped in their daily routines and food choices. A change in food preference towards sweet foods is very characteristic. Of importance is the fact that simple bedside cognitive screening tests such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) are insensitive at detecting frontal abnormalities. More detailed neuropsychological tests of frontal function (such as the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test or the Stroop Test) usually show abnormalities. Speech output can be reduced with a tendency to echolalia (repeating the examiner’s last phrase). Memory is relatively spared in the earl stages, although it does deteriorate as the disease advances. Visuospatial function remains remarkably unaffected. Primary motor and sensory functions remain normal. Primitive refl exes such as snout, pout, and grasp develop during the disease process. Muscle fasciculations or wasting, particularly affecting the bulbar musculature, can develop in the FTD subtype associated with MND.”

Memory tests, mild cognitive impairment and dementia of Alzheimer type

Nobody can deny the undeniable benefits of a prompt diagnosis, when correct, of dementia, but the notion that not all memory deficits mean dementia is a formidable one. Besides, this tweeted by Prof Clare Gerada, Chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners, to me this morning I feel is definitely true,

A political drive, almost in total parallel led by the current UK and US governments, to screen older people for minor memory changes could potentially be leading to unnecessary investigation and potentially harmful treatment for what is arguably an inevitable consequence of ageing. There are no drugs that prevent the progression of dementia according to human studies, or are effective in patients with mild cognitive impairment, raising concerns that once patients are labelled with mild cognitive deficits as a “pre-disease” for dementia, they may try untested therapies and run the risk of adverse effects.

The idea itself of the MCI as a “pre-disease” in the dementia of Alzheimer type is itself erroneous, if one actually bothers to look at the published neuroscientific evidence. A mild cognitive impairment (“MCI”) is a clinical diagnosis in which deficits in cognitive function are evident but not of sufficient severity to warrant a diagnosis of dementia (Nelson and O’Connor, 2008).It is claimed that on the CANTABmobile website that:

![]() However, the evidence of progression of MCI (mild cognitive impairment) to DAT is currently weak. It might be attractive to think that MCI is a preclinical form of dementia of Alzheimer Type, but unfortunately the evidence is not there to back this claim up at present: only approximately 5-10% and most people with MCI will not progress to dementia even after ten years of follow-up (Mitchell and Shiri-Feshki, 2009).

However, the evidence of progression of MCI (mild cognitive impairment) to DAT is currently weak. It might be attractive to think that MCI is a preclinical form of dementia of Alzheimer Type, but unfortunately the evidence is not there to back this claim up at present: only approximately 5-10% and most people with MCI will not progress to dementia even after ten years of follow-up (Mitchell and Shiri-Feshki, 2009).

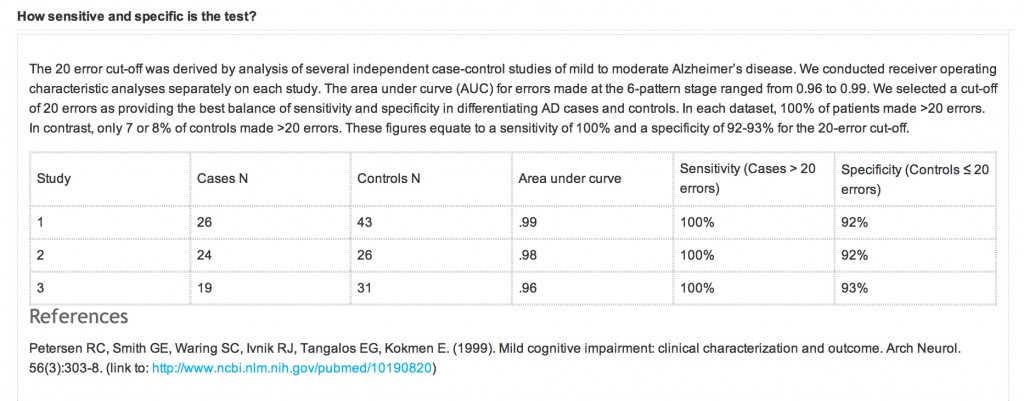

An equally important question is also the specificity and sensitivity of the CANTABmobile PAL test. Quite a long explanation is given on their webpage again:

However, the reference that is given is unrelated to the data presented above. What should have appeared there was a peer-reviewed paper analysing sensitivity and sensitivity of the test, across a number of relevant patient groups, such as ageing ‘normal’ volunteers, patients with geriatric depression, MCI, DAT, and so on. A reference instead is given to a paper in JAMA which does not even mention CANTAB or CANTABmobile.

NICE, QOF and indicator NM72

A description of QOF is on the NICE website:

“Introduced in 2004 as part of the General Medical Services Contract, the QOF is a voluntary incentive scheme for GP practices in the UK, rewarding them for how well they care for patients.

The QOF contains groups of indicators, against which practices score points according to their level of achievement. NICE’s role focuses on the clinical and public health domains in the QOF, which include a number of areas such as coronary heart disease and hypertension.

The QOF gives an indication of the overall achievement of a practice through a points system. Practices aim to deliver high quality care across a range of areas, for which they score points. Put simply, the higher the score, the higher the financial reward for the practice. The final payment is adjusted to take account of the practice list size and prevalence. The results are published annually.”

According to guidance on the NM72 indicator from NICE dated August 2013, this indicator (“NM72″) comprises the percentage of patients with dementia (diagnosed on or after 1 April 2014) with a record of FBC, calcium, glucose, renal and liver function, thyroid function tests, serum vitamin B12 and folate levels recorded up to 12 months before entering on to the register The timeframe for this indicator has been amended to be consistent with a new dementia indicator NM65 (attendance at a memory assessment service).

Strictly speaking then QOF is not about screening as it is for patients with a known diagnosis of dementia. If this battery of tests were done on people with a subclinical amnestic syndrome as a precursor to a full-blown dementia syndrome with an amnestic component, it might conceivably be ‘screening’ depending on how robust the actual diagnosis of the dementia of those individuals participating actually is. As with all these policy moves, it is very easy to have unintended consequences and mission creep.

According to this document,

“There is no universal consensus on the appropriate diagnostic tests to be undertaken in people with suspected dementia. However, a review of 14 guidelines and consensus statements found considerable similarity in recommendations (Beck et al. 2000). The main reason for undertaking investigations in a person with suspected dementia is to exclude a potentially reversible or modifying cause for the dementia and to help exclude other diagnoses (such as delirium). Reversible or modifying causes include metabolic and endocrine abnormalities (for example, vitamin B12 and folate deficiency, hypothyroidism, diabetes and disorders of calcium metabolism).

The NICE clnical guideline on dementia (NICE clinical guideline 42) states that a basic dementia screen should be performed at the time of presentation, usually within primary care. It should include:

- routine haematology

- biochemistry tests (including electrolytes, calcium, glucose, and renal and liver function)

- thyroid function tests

- serum vitamin B12 and folate levels.”

It is vehemently denied that primary care is ‘screening’ for dementia, but here is a QOF indicator which explicitly tries to identify reversible causes of dementia in those with possible dementia.

There are clearly issues of valid consent for the individual presenting in primary care.

Prof Clare Gerada has previously warned to the effect that it is crucial that QOF does not “overplay its hand”, for example:

“QOF is risking driving out caring and compassion from our consultations. We need to control it before it gets more out of control – need concerted effort by GPC and RCGP.”

Conclusion

Never has it been more important than to heed Prof Brayne’s words:

“As a group of clinical and applied researchers we urge governments, charities, the academic community and others to be more coordinated in order to put the policy cart after the research horse.”

In recent years, many glib statements, often made by non-experts in dementia, have been made regarding the cognitive neuroscience of dementia, and these are distorting the public health debate on dementia to its detriment. An issue has been, sadly, a consideration of what people (other than individual patients themselves) have had to gain from the clinical diagnosis of dementia. At the moment, some politicians are considering how they can ‘carve up’ primary care, and some people even want it to act as a referral source for private screening businesses. The “NHS MOT” would be feasible way of the State drumming up business for private enterprises, even if the evidence for mass screening is not robust. The direction of travel indicates that politicians wish to have more ‘private market entrants’ in primary care, so how GPs handle their QOF databases could have implications for the use of ‘Big Data’ tomorrow.

With headlines such as this from as recently as 18 August 2013,

this is definitely ‘one to watch’.

Further references

Beck C, Cody M, Souder E et al. (2000) Dementia diagnostic guidelines: methodologies, results, and implementation costs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 48: 1195–203

Mitchell, A.J., and Shiri-Feshki, M. (2009) Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia -meta-analysis of 41 robust inception cohort studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 119(4), pp. 252-65.

Nelson, A.P., and O’Connor, M.G. (2008) Mild cognitive impairment: a neuropsychological perspective, CNS Spectr, 13(1), pp. 56-64.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2006) Dementia. Supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. NICE clinical guideline 42