Home » Posts tagged 'regulation'

Tag Archives: regulation

Who exactly is in denial over the Clive Efford Bill?

The Private Member’s Bill brought forward by backbencher Clive Efford MP passed by 241 votes to 18.

“From crisis to opportunity — putting citizens and companies on the path to prosperity: A better functioning internal market is a key ingredient for European growth” was updated in November 2014.

This publication is part of a series that explains what the EU does in different policy areas, why the EU is involved and what the results are.

It provides that, “The European internal market, also referred to as the single market, allows people and businesses to move and trade freely across the 28-nation group. In practice, it gives individuals the right to earn a living, study or retire in another EU country.”

It further adds that, “It also gives consumers a wider choice of items to buy at competitive prices, allows them to enjoy greater protection when shopping at home, abroad or online and makes it easier and cheaper for companies large and small to do business across borders and to compete globally.”

Not wanting to be part of Europe was of course how the late great Tony Benn used to be in agreement with Enoch Powell, even though they came from totally different political stables.

On 1 January 1973, Britain joined the “Common Market”, the European Economic Community, under a previous Conservative administration.

There has of course been a strident debate as to whether the free movement of capital, so important for capitalism, is inherently compatible with socialism at all.

Being a member of the EU, the UK has to sign up to the rules and regulations of EU law.

The current position of Labour is that the market ideology went too far under previous Labour administrations.

Critics of Labour say that they are still in denial over the “sweetheart deals” to encourage private provision under a previous administration. Labour argues that this private provision was necessary to improve clear a backlog in NHS work which existed at the time, rather than introducing private provision for the sake of it.

Much criticism centres around the “independent sector treatment centres”. John Rentoul unsurprisingly found himself in agreement with the approach Labour took at the time.

Many still within Labour still loathe what happened here. NHS campaigners affiliated to other parties have been critical of Labour in inadvertently contributing to the privatisation of the NHS, and are concerned it will happen again.

Critics point to unconscionable transactions under the private finance initiative, for example.

But historically this strand of policy started under a previous Conservative administration under Lord Major.

Clive Efford MP even referred to his local hospital in Eltham having been set up as the country’s first PFI hospital in last week’s debate on “The Clive Efford Bill”.

Given that we are under treaty obligations, unless there were a radical renegotiation of an unilateral exemption of the market aspect of the EU, we are stuck with a market in some form.

To argue otherwise would be in denial.

None of the front team of Labour have argued for abolition of the market altogether, to my knowledge.

But that is not to say that the ‘purchaser provider split’ might be abolished internally within England, notwithstanding treaty obligations.

The argument is that the market costs billions as it introduces “transaction costs”. The ‘household analogy’ is often used to explain the diversion of resources needed to monitoring the various transactions within a household at microlevel.

The market has become particularly problematic for the NHS, as was widely predicted before the Health and Social Care Act (2012). I myself wrote an article on the impact that section 75 Health and Social Care Act (2012) would have on the Socialist Health Association blog on 7 January 2013.

And the former CEO of NHS England, Sir David Nicholson, himself drew attention to how it had become a magnet for competition lawyers.

This was entirely to be expected as it was this clause which signalled a marked diversion from previous law under the most recent Labour government (viz section 76 sub 7 Health and Social Care Act 2012).

Elsewhere in the legislation it says that you do not have to put contracts out to competitive tender if there is only one sole bidder, which hardly ever happens.

To deny that the current legislation departs from the previous legislation is, arguably, denial.

So the “Clive Efford Bill” was finally debated last week. You can read it here. The official explanatory notes for the Bill are here.

The guidance given to the legislature is useful.

For example, for clause 6, it is provided: “The clause also enables the NHS to take advantage of exemptions to procurement obligations as set out in the European Union Directive 2014/24/EU.”

The Directive provides the ‘codification of the Teckel exemption‘.

The Teckel Exemption has proved important as an exemption from EU competition law when applied to the NHS.

Clause 1 posits that the NHS is a system based on ‘social solidarity’.

Solidarity is another mechanism of providing an exemption from EU competition law. In fact, the lack of solidarity was one of the criticisms of the Health and Social Care Bill made at the time made by ‘Richard Blogger’.

The Poucet and Pistre Case C-159, 160/91 case sheds light not heat on the ‘social solidarity’ exemption of competition law.

A reasonable concern is whether the ‘Clive Efford Bill’ hangs on by its claws to the notion of the NHS being comprised of ‘units of economic activity’ as per s.1 sub (2)(b):

But here it is the “Clive Efford Bill” which may be in denial.

Scrutiny in the Committee stage will have to be given as to whether the term here should be “general economic interest” or “general interest”.

The Government’s own guidance on this implementation of EU law is here.

If the direction of travel for all mainstream governments is genuinely to keep the proportion of private provision low, “general interest”, arguably, would be more suitable if the majority of health provision is not intended for profit.

It has been a consistent mantra from the Labour front bench “to put people before profit”, for example.

There are other issues about the significance of the words ‘deliver’ and ‘promote’ in the duty of the Secretary of State for Health.

The view of David Lock QC is here. The view of “The Campaign for the NHS 2015 Reinstatement Bill” is here.

Would a rose by any other name smell as sweet? It is a deeply entrenched position of the legal profession that lawyers look at the substance not the form.

As a statutory aid to the wording of this legislation, there is this paragraph lurking on the internet from David Lock QC from June 2013 which lends support to the notion that it is most useful if the ‘Clive Efford Bill’ is a statutory instrument best read as a whole.

Assuming that events do not overtake us, in other words we do not get chucked out of Europe imminently or the UK does not get bound in indefinitely over TTIP, we should in theory have some freedom to legislate for what sort of health service we want.

This is provided for in Article 168(7) TFEU.

It is therefore crucial we draft this legislation correctly.

Taking the position that there must be no criticism of the drafting of the Clive Efford Bill, arguing that it will undermine its implementation at Committee Stage, I think is an unreasonable position to adopt.

Likewise, grandstanding over “who is right” is inappropriate as well. There are possibly as many legal opinions as there are lawyers. We will not know with any certainty unless the Clive Efford Bill, if enacted, is put to the test by the judiciary; and even then, it will not be absolutely certain.

I think the Clive Efford Bill clearly positions itself as exempting itself from the overall gambit of EU competition law.

“It says what it does on the tin”. It is an immediate mechanism, if enacted, for getting rid of the toxic section 75 and baggage. It has been a useful campaigning tool.

But, if there is a Labour government of some sort in May 2015, it is already proposed that there will be regulation of health and care professionals as per the recommendations of the English Law Commission. This should have been in the last Queen’s Speech just gone, but the current Government chose to park this issue. Furthermore, quite drastic changes to the law will still be needed to promote integration of health and care to make whole person care work smoothly and legally. I first wrote about that issue here on this blog in June 2013. Decisions, made on clinical grounds, must be clear of competition obstructions, Enmeshing the NHS with the Enterprise Act over mergers has been a disastrous development in national policy, for example witnessed in the Bournemouth and Poole merger.

So it’s pretty likely that “The Efford Win” is the opening salvo in a war for the soul of the NHS. Time will tell whether UKIP are genuinely against privatisation. I’d bet my life on the fact are far from cuddly socialists. Their policy across a number of areas changes very rapidly, so only time will tell. The more parsimonious explanation is that UKIP are acting completely opportunistically, and wish to win seats off disaffected members across all the mainstream parties. A Labour-UKIP coalition would be very difficult to implement, whatever one thinks of Ed Miliband’s ability to negotiate a bacon butty.

Scrapping the Human Rights Act does not get rid of Strasbourg as a portal of action for health and care matters

Like most people who’ve had a legal training, I was baffled why David Cameron is so triumphant about scrapping the Human Rights Act (1998). The legal position is that “British citizens would still be able to take cases to the European court of human rights, and its case law and the principles of the convention would still be in force in UK courts.”

This is stated correctly here.

Leading commentators such as Joshua Rozenberg, Britain’s best known legal commentator, have previously advised that the debate must be conducted in a different light from the political grandstanding (article here).

When Dominic Grieve, the previous Attorney General, was asked at a fringe meeting for his reaction to May’s speech, he insisted he was “completely comfortable” with the idea of replacing the existing legislation with a British bill of rights.”

At the time, it was observed that Ken Clarke QC MP, like Dominic Grieve QC MP, was a keen supporter of human rights.

In 2011, when I was studying my Master of Law, I attended discussion at the Honourable Society of Inner Temple last night. The seminar is jointly hosted by the Constitutional and Administrative Bar Association (ALBA) and the new Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law. The speakers included Lord Justice Laws, Lord Pannick QC and Professor Philip Leach, London Metropolitan author, and author of numerous publications including the book “Taking a case to the European Court of Human Rights”. The session was totally packed out, and the speakers took many questions from leading practising international barristers and academics.

It is perhaps easy to overstate the opposition towards the Human Rights Act, but it was pointed out only two countries are openly questioning the legitimacy of the European Convention of Human Rights – Russia and the United Kingdom.

LJ Laws has long been in favour of developing domestic jurisprudence in the context of the Human Rights Act and common law.

He opined at this event that “the cases were beginning to speak, but the Convention was an useful guidance”, and reaffirmed the influence of a graduated approach to proportionality, an argument which Laws noted had been accepted by Bingham (see for example Regina v. Secretary of State For The Home Department, Ex Parte Daly). Laws reminded the legal audience that we, as a country, have always been in a position to influence Strasbourg, as for example the Pretty v United Kingdom case.

Laws further mooted, however, why should the judges be deciding upon social policy. Considering particularly articles 8-12, Laws provided that often lawyers had to decide where to strike the balance in certain issues between competing interest, but fundamentally lawyers were there to establish the framework and issue – however Laws warned that the nature of this exercise in jurisprudence gives rise ultimately to issue of a philosophical nature. I found this academic exploration by Laws interesting in light of how human rights law might impact on aspects of health and care policy in England.

Lord Pannick charted the history of the reaction to our history right legislation, in relation to Strasbourg. Pannick reminded the audience that criticising the Human Rights Act, in relation to Europe, was not a recent phenomenon.

In relation to the Gilbraltar incident, Michael Heseltine – as far back as 1995 – said, “We shall do nothing. We will pursue our right to fight terrorism to protect innocent people where we have jurisdiction, and we will not be swayed or deterred in any way by the ludicrous decisions of the Court.”

According to Lord Pannick, prisoners’ voting rights and the use of hearsay have also produced conflicting opinions from the UK and Strasbourg, and indeed these legal conflicts appear to be ongoing (see for example the present case of Zainab al-Khawaja, where the original argument was heard by the Court in 2010).

Lord Pannick proposed that this conflict arose from various sources. Firstly, Lord Pannick felt there is a general resentment of European law amongst Conservative “elements”, and many of the population. Secondly, the objection to the European Convention of Human Rights could part of a wider objection to foreign law. Lord Pannick indeed reminded the audience that a Conservative MP, lawyer and judge, David Maxwell-Ffye, was instrumental in drafting the European Convention of Human Rights. Lord Pannick then identified a possible perception from the UK voting public, that judges should not be deciding on social policy: for example, the argument for prisoner voting is not a matter for judges, but should be a matter for parliament.

Lord Pannick did not feel fundamentally that the criticisms of the HRA amounted to much. For example, the HRA expressly recognises that the UK Parliament is not bound by the Convention. If Parliament wishes to exclude voting by prisoners, the Human Rights Act does not prevent this. The judges can decide whether the defendants comply, but, according to Lord Pannick, it is equally important that the last word lies with parliament. Lord Pannick instead felt that a much more difficult issue is the relationship between parliament and the Strasbourg Court.

A future ‘all Conservative’ government, even if it repealed the HRA would still leave the jurisdiction of the Strasbourg Court intact – our own judges have no effect on the jurisprudence.

If the 1998 Act were to be repealed, as parliament is overeign, the number of British cases to Strasbourg would increase according to Lord Pannick. Lord Pannick felt that an useful to look at the relationship between our Supreme Court and Strasbourg would be to look at the ‘control of its docket’ jurisprudence, in other jurisdictions of international law.

Lord Pannick ultimately felt that the power of our parliament to define power Strasbourg as a body is limited. It would be unprecedented for us to withdraw from the European Convention of Human Rights, incompatible with membership of the EU, or Council of Europe. According to Lord Pannick, the concept of European minimum standards is of vital importance to us. There may be be occasions when national or international considerations are that our judges do not originally recognise that human rights are being breached (e.g. gays in the military) It would be difficult for us to expect that other countries such as Russia should comply with the Convention, if we do not. Lord Pannick therefore felt that the situation now required an accommodation on both sides.

The Strasbourg is supposed to overrule a National court only in cases of fundamental significance, where the national supreme court has made an error of principle. If Strasbourg does not follow this principle, it may risk the growth of political opposition. However, likewise, Lord Pannick identified that the Supreme Court should not supinely follow Strasbourg, either. The Government for example accepted the DNA ruling in preference ot the House of Lords. If the Supreme Court were to be asked if the voting rule asked about the prisoners’ voting again, Lord Pannick felt that the Supreme Court would be unlikely to say it is compatible with the European Convention of Human Rights.”

The Human Rights Act (1998) is also relevant to aspects of policy relating to people’s health: there have been concerns whether the ‘welfare reforms’ have offended human rights legislation.

There have also been concerns whether the fitness to practise procedures of the GMC need to be explored with the human rights lens?

There are also further issues, unresolved as yet, about whether the Health and Social Care Act (2012) offends humans rights legislation.

Most of this blogpost was first published on Dr Shibley Rahman’s legal blog here.

Out of sight, out of mind

Please note: This blogpost has been edited since the first publication, due to a factual inaccuracy of mine this morning where I stated the Tavistock Clinic was private.

It is not private. I do sincerely apologise for this mixup. It was an entirely accident error of mine.

I have also changed the word ‘aggressive treatments’ to ‘thorough interventions’ on the advice of two different people.

I am further posting Kate’s very helpful comment below the end of this article.

I am extremely grateful to Kate for her comment.

________________________________________________________________________________________

I have previously written openly about my personal experiences as a sick doctor and beyond (please see here). Thank you if you were one of the 2000 or views of that blogpost on that particular day.

In 2008, the Department of Health under the previous government funded a two year pilot to commission and provide a specialist, confidential, service, the Practitioner Health Programme (PHP).

The service was free to all doctors and dentists in London with:

- mental health or addiction concern (at any level of severity); and,

- physical health concern (where that concern was potentially impacting on the practitioner’ performance).

The PHP complemented existing NHS GP, occupational health and specialist services. It demonstrated the need for the service (over 500 patients have now been treated, many with complex problems) and how savings could be achieved through swift, safe return to work.

The 2009 Boorman review of the health of the NHS workforce reported that:

- the direct costs of ill-health in NHS staff are in the region of £1.7 billion p.a.;

- the agency staff bill for the NHS is around £1.45 billion p.a. (spending closely related to sickness absence and staff turnover); and 2,500 ill-health retirements (some possibly preventable) each year cost the NHS £150m p.a.

The Chief Executive of the General Medical Council, Niall Dickson, commenting on the PHP said:

“We know of the stress and anguish experienced by doctors who become sick and how this can affect their work. There is not enough good support at local level and the PHP programme has shown what can be done.”

It is now pretty widely felt that prevention and early intervention could save the NHS millions of pounds, and employers can achieve huge savings by supporting doctors and ensuring they remain fit to practise, whilst maintaining or improving quality. The potential savings for employers far outweigh the likely cost of establishing a nationwide service (estimated at around £6 million). There is therefore a real economic case, as well as averting tragedies in human lives training in the NHS.

If you’re a sick Doctor, ‘Good medical practice’, the GMC’s code of conduct, is triggered under domain 2 for quality and safety by the following clause.

In my own particular case, it is recorded in two detailed witness statements that I tried to discuss in detail the alcohol problem that was concerning me with two Consultant Physicians in London.

In neither case was I offered a programme of alcohol management. I confided in them personal details.

It is a real pity that I did take up an offer by a Consultant who recommended the Tavistock Clinic, as I erroneously thought it was private not public. Notwithstanding that, no offer of sick leave was made, but that is my fault for not having let the discussion get that far.

But I really don’t wish to play any ‘blame game’ – for example I failed in not being under a General Practitioner at the time, as I was at that stage absolutely petrified that that GP would have reported me to the GMC subjecting me to years of investigation. I had years of investigation anyway, but without the critical help I needed.

Being under a General Practitioner for a medical professional is a requirement of their Code of Conduct according to rule thirty.

I think many aspects of my dire situation reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of the medical profession thinking that if a sick Doctor is ‘aware’ of his problem he has full insight into the distress the problem is causing to friends, family and beyond.

I feel that, had my problem been aggressively dealt with earlier, the subsequent failures in my alcohol management would not have occurred (three years later).

My erasure for me was perceived by me as the ultimate personal failure for having been through a public hearing, treated still in the media as a “show trial”, and a personal failure for not having got clinically better. On a note of wider contrition, however, I have no objection to the issues I was found proven to this day, and I think the GMC ultimately made the correct sanction.

Media reports, despite public humiliation, distressing not just for me but my late father at the time, make no reference to my underlying medical problems. I was sectioned in May 2006 due to alcoholism. It’s as if the establishment wishes purposefully to airbrush doctors being sick.

I was distraught on my erasure, for having no solution to my mental health problems in sight. The regulatory process exacerbated my misery, with psychiatrists not being able to rule out at anxiety and depressive component while I was heavily drinking.

I know I was ‘aware’ of my problem with empty drunk bottles of red wine, but it doesn’t mean that I had the motivation to take time off work then to do something about it.

Likewise, the GMC code (see clause twenty eight above) assumes that the sick Doctor has full insight.

In my case, it had a very unpleasant end.

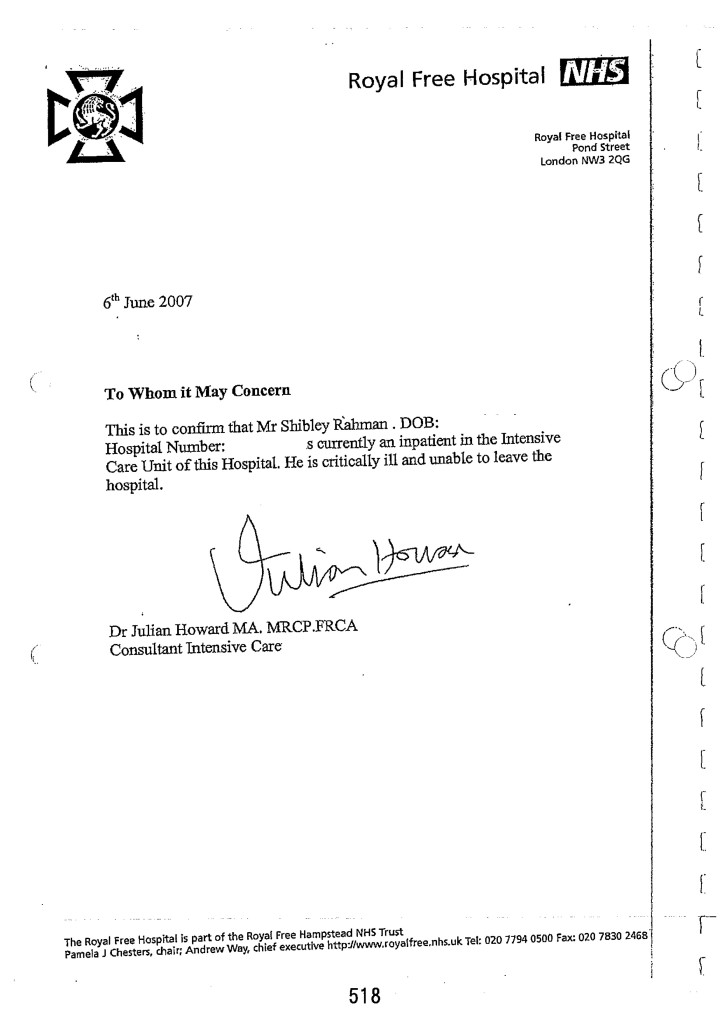

Not just this, days before my 33rd birthday,

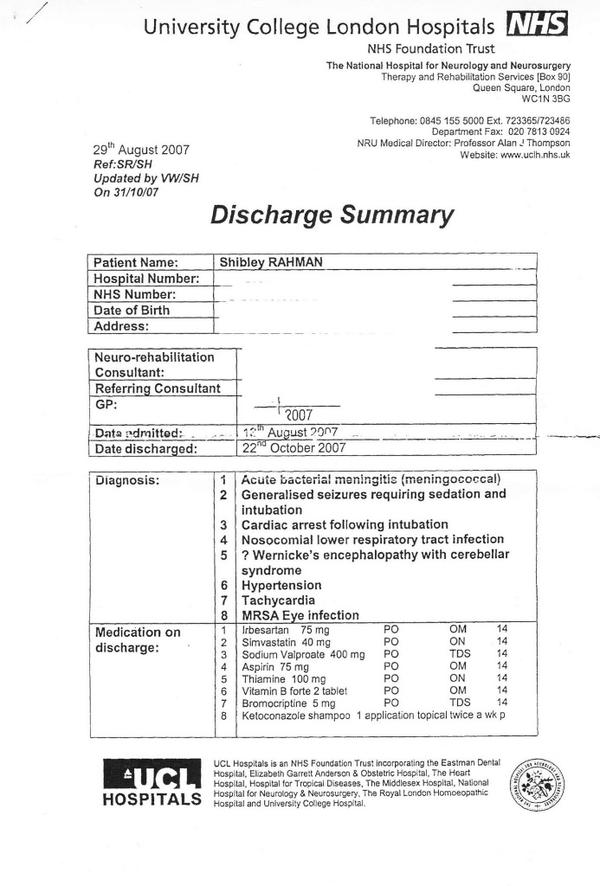

but this six week coma and two month neurorehabilitation (the full discharge diagnosis from a place where I used to be a junior clinical physician once with no health problems.)

I think it is incredibly hard for anyone to understand outside of the system how you get raped of your dignity and integrity by the regulator when you fail to improve from mental illness. And often this mental illness is exacerbated by the regulatory process, as 86 deaths of Doctors awaiting Fitness to Practice during the same period of my investigation might appear to testify.

As I never had a performance assessment or clinical supervisor during my regulatory process, despite four different consultants concluding I had a severe alcohol problem at least between August 2004 and spring 2005, I feel I was put into managed decline long before the final hearing in July 2006.

I think personally the system for sick doctors undergoing the regulatory process from the General Medical Council could be much better, but that might be just be an unfortunate personal experience: ‘there’s nothing to see here’.

But a good first management step for me would be to roll out the Practitioner Health Programme to a jurisdiction wider than London. Lives truly depend on it, and the general public deserve better from seniors in the medical profession. This, for me, is absolutely necessary to maintain trust in the medical profession, domain 4 of the current GMC Code of Conduct. The GMC need to make the dealings open in this regard, fundamentally.

As far as the Consultants who contributed to my 2006 erasure were concerned, I have been out of sight and out of mind. In fact, I haven’t spoken to them for a decade and needless to say they have not wished to contact me.

I may be newly physically disabled following 2007.

I don’t personally wish the GMC any ill will. I believe in rehabilitation being a regulated student member of the law profession now – but do they?

I am back now.

Kate’s really helpful comment:

The Med Net service IS FREE and confidential.

When medical trainees encounter difficulties, college tutors, clinical tutors, programme directors and educational supervisors are encouraged to signpost them to Med Net. It was very positive that the consultant, who was not your educational supervisor, took sufficient pastoral interest in your welfare to give you the Med Net contact details. Ultimately, it is down to junior doctors to contact the service. Had you sought an appointment with your trusts OH team, they’d have given you the same contact details. It would have still been down to you to make contact. (< Indeed. Thanks , noted )

Alcohol-related disorders are outside the Mental Health Act, so it is impossible to compel people to undergo “treatment”. “Treatment” is an unfortunate term, as there is little that therapists can do until an individual wants help or becomes so incapacitated that they cease using. Even then, the notion of “treatment” as something that is done “to” people is inappropriate. This is one of the reasons why addictive disorders are outwith the MHA. Compulsion doesn’t work. “Aggressive treatment” is a particularly unhelpful concept more appropriate for the treatment of leukaemia rather than substance misuse disorders. Intense cycles of chemo-irradiation may induce remission in oncology, but intense input achieves nothing in addiction.

Kate then said it was a pity that I did not take up the offer of that Consultant, which I absolutely agree with.

Now that Maria Miller’s finally left, it’s time to welcome ‘dementia pharma’ to the last chance saloon

In everyday English, a “last chance saloon” means a situation beyond all rational hope.

After decades of working on drugs for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the best the industry can manage is some drugs which have some effect on symptoms for a few months, but for which there’s no evidence they delay the progression in the long term.

Big Pharma have maintained this deception uptil the very last minute, indeed uptil the patents ran out.

They know they’re now drinking at “the last chance saloon”.

David Cameron backed Maria Miller, and that failed.

He backed the Big Society, and that failed.

Now he has backed research into dementia-busting medications.

After a 16-month inquiry, a verdict was reached on Maria Miller.

Commissioner Hudson found that Miller should have designated the Wimbledon property as her main residence, that she should have reduced her claims by two-sevenths to take account of her parents’ presence and that she overclaimed for interest on the mortgage by around £45,000.

Nonetheless, there was no indication Miller had done anything unlawful or illegal in her deception.

On the other hand, the Japanese drugs company Takeda was fined a record £3.6bn ($6bn) by a federal court in the United States on 8 April 2014 following claims that it concealed a possible link between the drug pioglitazone and bladder cancer.

The fine is the largest to be imposed on any pharmaceutical company.

Takeda’s US partner Eli Lilly, who marketed and sold pioglitazone in the United States between 1999 and 2006, also received a £1.79bn ($3bn) fine.

The diabetes drug pioglitazone, marketed as Actos in the US, received marketing authorisation in Europe in 2000. Actos is marketed and sold in the United Kingdom by Takeda UK Ltd.

Today we found out that Tamiflu doesn’t work so well after all. Roche, the drug company behind it, withheld vital information on its clinical trials for half a decade, but the Cochrane Collaboration, a global not-for-profit organisation of 14,000 academics, finally obtained all the information.

Putting the evidence together, it has found that Tamiflu has little or no impact on complications of flu infection, such as pneumonia.

The huge scandal, of course, is that scandal Roche broke no law by withholding vital information on how well its drug works.

Elsewhere, standardised tobacco packaging is intended to reduce the appeal of tobacco products by removing advertising and increasing the prominence of health warnings.

This measure has strong support from health professionals, particularly as rates of child uptake of smoking are still unacceptably high.

Tobacco industry misrepresentation of the evidence in order to try to block public health interventions by manipulating policy making and public opinion is now well documented.

On March 2011, the National Health Service’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) concluded that donepezil hydrochloride (trade name Aricept, Pfizer) could be ‘recommended as (an option) for managing mild as well as moderate AD’.

The conclusion was drawn despite reportedly poor cost efficacy3 and opinions that the use of the drug is a ‘desperate measure’.

The NICE decision was based on two meta-analyses (the second was an update of the first) of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that demonstrated donepezil’s effect on measures of cognition, behaviour, function and global skills.

Of the 19 studies included, 12 were produced by the companies that manufacture and market donepezil. And a recent study has found that the effect size of donepezil on cognition is larger in industry-funded than independent trials and this is not explained by the longer duration of industry-funded trials.

The history of anti-dementia drugs is inglorious. This is significant because every pound spent in flogging this dead horse is a pound denied from current persons living well with dementia.

Tacrine is an oral acetylcholinesterase inhibitor previously used for therapy of Alzheimer disease. Tacrine therapy has been linked to several instances of clinically apparent, acute liver injury.

Because of continuing concerns over safety and availability of other acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, tacrine was withdrawn from use in 2013.

And it is widely reported that current candidate drugs for Alzheimer’s disease are running into problems because of their side effect profile.

Maria Miller may have finally left the ‘last chance saloon’.

But it can’t have escaped Big Pharma, despite ‘the G8 dementia summit’, possibly the largest PR stunt for pharma and research funded by pharma in history, that they are currently drinking there.

The deceptions might be so far be legal.

Maria Miller’s claims might have been hyperbolic; at least she didn’t have a highly staged G8 summit afterwards.

But, as with Maria Miller, the court of public opinion may provide otherwise.

The ubiquitous failure to 'regulate culture' speaks volumes

It is alleged that a problem with socialists is that, at the end of the day, they all eventually run out of somebody else’s money. Perhaps more validly, it might be proposed that the problem with all politicians is that they all run of other people to blame?

It is almost as if politicians form in their minds a checklist of people they wish to nark off systematically when they get into government: candidates might include lawyers, Doctors, bankers, nurses, disabled citizens, to name but a few.

Politicians are able to use the law as a weapon. That’s because they write it. The law progressively has been reluctant to decide on moral or ethical issues, but altercations have occurred over potentially inflammable issues such as ‘the bedroom tax’. Normative ethics takes on a more practical task, which is to arrive at moral standards that regulate right and wrong conduct.

There has always been a tension between the law and ethics. As an example, to prove an offence in the English criminal law, you have to prove beyond reasonable doubt an intention rather than a motive, for example that a person intended to burn someone’s house down, rather than why he had intended so. Normative ethics involve articulating the good habits that we should acquire, the duties that we should follow, or the consequences of our behaviour on others. The ultimate ‘normative principle’ is that we should do to others what we would want others to do to us.

Parliament is about to get its knickers in a twist once again over the thorny issue of press regulation. However, there is a sense of history repeating itself. A few centuries ago, “Areopagitica” was published on 23 November 1644, at the height of the English Civil War. It is titled after Areopagitikos (Greek: ?????????????), a speech written by the Athenian orator Isocrates in the 5th century BC. (The Areopagus is a hill in Athens, the site of real and legendary tribunals, and was the name of a council whose power Isocrates hoped to restore).

“Areopagitica” was distributed via pamphlet, defying the same publication censorship it argued vehemently against. As a Protestant, Milton had supported the Presbyterians in Parliament, but in this work he argued forcefully against the Licensing Order of 1643, in which Parliament required authors to have a license approved by the government before their work could be published.

Milton then argued that Parliament’s licensing order will fail in its purpose to suppress scandalous, seditious, and libellous books: “This order of licensing conduces nothing to the end for which it was framed.” Milton objects, arguing that the licensing order is too sweeping, because even the Bible itself had been historically limited to readers for containing offensive descriptions of blasphemy and wicked men.

England has for a long time experienced problems with moving goalposts in the law, and indeed the judicial solutions sought have varied with the questions being asked. Lord Justice Leveson acknowledged that the “world wide web” was a medium subject to no central authority and that British websites were competing against foreign news organisations, particularly in America, which were part of no regulatory system.

Leveson once nevertheless proposed that newspapers should still face more regulation than the internet because parents can ‘to some extent’ control what their children see online, while they could not control what they see on a newsagent or supermarket shelf.

‘It is clear that the enforcement of law and regulation online is problematic,’ said Lord Justice Leveson at the end of his year-long inquiry into press ethics.

An attempt at ‘regulating culture’ was dismissed in the Leveson Report largely through arguing that the offences were substantially already ‘covered’, such as trespass of the person or phone hacking. And yet it is the case that there are ‘victims of phone hacking’ who feel that we are unlikely to be much further forward than we were before spending millions on an investigation into journalistic practices. In recent discussions this week, eyebrows have been raised at the suggestion that Ed Miliband could write to senior members in the Mail-on-Sunday empire to suggest that the culture in their newspapers is awry, and to ask them to do something about it. It could be argued it is none of Miliband’s business, except that Miliband would probably prefer the Mail to write favourably about him. Such flexibility in judgments might be on a par with Mehdi Hasan changing his writing style and target audience within a few years, as the recent Twitterstorm demonstrates.

The medical and nursing professions have latterly urged for an approach which is not overzealously punitive. There have been very few sanctions for regulatory offences in Mid Staffs or Morecambe Bay, for example.

Robert Francis QC still identified that an institutional culture which put the “business of the system ahead of patients” is to blame for the failings surrounding Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust. Announcing the publication of his three volume report into the Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust public inquiry, Mr Francis described what happened as a “total system failure”.

Francis argued the NHS culture during the 2005-2009 period considered by the inquiry as one that “too often didn’t consider properly the impact on patients of decisions”. However, he said the problems could not “be cured by finding scapegoats or [through] reorganisation” of the NHS but by a “real change in culture”. However, having identified the problem, solutions for cultural ‘failure’ in the NHS have not particularly been forthcoming.

There are promising reports of ‘cultural change’ in the NHS, for example at Mid Staffs and Salford, but some aggrieved relatives of patients still have a feeling that ‘justice has not been done’. There has been no magic bullet from the legislature over concerns about bad practice in the NHS, and it is unlikely that any are immediately forthcoming. There is little doubt, however, that parliament improving the law on safe staffing or how whistleblowers can raise issues in the public interest safely might be constructive steps forward. There therefore exists how the law might conceivably ‘improve’ the culture, and one suspects that this change in culture will have to permeate throughout the entire organisation to be effective. That is, fundamentally, people are not punished for speaking out safely, and, whilst legitimate employers’ interests will have to be protected, the protection for employees will have to be necessary and proportionate equally under such a framework.

Journalism and the NHS are not isolated examples, however, Newly released reports into the failures of management at several major banks – HBOS, Barclays, and JP Morgan among them – show that some of the worst losses had roots deeper than the 2008 credit crisis. It is said that a toxic internal culture and poor management, not the subprime mortgage collapse, caused billion-dollar losses at some of the world’s largest banks

In an argument akin to that used to argue that there is no need to regulate the journalism industry, the banking industry have long maintained that a strong feeling of internal competition can be healthy for profitability, but problems such as abject fraud and misselling of financial products are already illegal.

The situation is therefore a nonsense one. There is a failed culture, ranging across several diverse disciplines, of politicians wishing to use regulation to correct failed cultures. Cultures of an organisation, even with the best will in the world, can only be changed from within, even if the public, vicariously through politicians, wish to impose moral and ethical standards from outside.

Whichever way you wish to frame the argument, it might appear ‘we cannot go on like this.’ It is a pathology which straddles across all the major political parties, and yet all the parties wish to claim that they have identified a poor culture.

Their lack of perception about what to do with these problems is perhaps further evidence that the political class is not fit for the job.

Information imbalances are the heart of many recent disasters

Had certain people at the BBC known about, and acted upon, the information which is alleged about Jimmy Savile, might things have turned out differently? George Entwhistle tried to explain yesterday in the DCMS Select Committee his local audit trail of what exactly had happened with the non-report by Newsnight over these allegations.

‘Information asymmetry’ deals with the study of decisions in transactions where one party has more or better information than the other. This creates an imbalance of power in transactions which can sometimes cause the transactions to go awry, a kind of market failure in the worst case. Information asymmetry causes misinforming and is essential in every communication process. In 2001, the Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to George Akerlof, Michael Spence, and Joseph E. Stiglitz for their “analyses of markets with asymmetric information.” Information asymmetry models assume that at least one party to a transaction has relevant information whereas the other(s) do not. Some asymmetric information models can also be used in situations where at least one party can enforce, or effectively retaliate for breaches of, certain parts of an agreement whereas the other(s) cannot.

In adverse selection models, the ignorant party lacks information while negotiating an agreed understanding of or contract to the transaction, whereas in moral hazard the ignorant party lacks information about performance of the agreed-upon transaction or lacks the ability to retaliate for a breach of the agreement. An example of adverse selection is when people who are high risk are more likely to buy insurance, because the insurance company cannot effectively discriminate against them, usually due to lack of information about the particular individual’s risk but also sometimes by force of law or other constraints. An example of moral hazard is when people are more likely to behave recklessly after becoming insured, either because the insurer cannot observe this behavior or cannot effectively retaliate against it, for example by failing to renew the insurance.

Joseph E. Stiglitz pioneered the theory of screening, and screening is a pivotal theme in both economics and medicine. In this way the underinformed party can induce the other party to reveal their information. They can provide a menu of choices in such a way that the choice depends on the private information of the other party.

Examples of situations where the seller usually has better information than the buyer are numerous but include used-car salespeople, mortgage brokers and loan originators, stockbrokers and real estate agents. Examples of situations where the buyer usually has better information than the seller include estate sales as specified in a last will and testament, life insurance, or sales of old art pieces without prior professional assessment of their value.

This situation was first described by Kenneth J. Arrow in an article on health care in 1963. The asymmetry of information makes the relationship between patients and doctors rather different from the usual relationship between buyers and sellers. We rely upon our doctor to act in our best interests, to act as our agent. This means we are expecting our doctor to divide herself in half – on the one hand to act in our interests as the buyer of health care for us but on the other to act in her own interests as the seller of health care. In a free market situation where the doctor is primarily motivated by the profit motive, the possibility exists for doctors to exploit patients by advising more treatment to be purchased than is necessary – supplier induced demand. Traditionally, doctors’ behaviour has been controlled by a professional code and a system of licensure. In other words people can only work as doctors provided they are licensed and this in turn depends upon their acceptance of a code which makes the obligations of being an agent explicit or as Kenneth Arrow put it “The control that is exercised ordinarily by informed buyers is replaced by internalised values”

In standard civil litigation, disclosure of information takes place between the two parties in standard proceedings, a party must disclose every document of which it has control and which falls within the scope of the court’s order for disclosure. Even if a party discloses a document, the other party is not entitled to inspect the document. Of course, this disclosure procedure might have effects in producing information imbalances, where it is important to see ‘the big picture’. Such a situation is the Leveson Inquiry, ultimately looking at how activities might be better regulated if appropriate (and by whom). The communications with the former News International chief executive and the News of the World editor-turned spin doctor, Andy Coulson, were reportedly kept from the hearings into press standards after the Prime Minister sought legal advice. Labour said that David Cameron, the UK Prime Minister, must make sure that “every single communication” that passed between him and the pair be made available to the inquiry and the public. The cache runs to dozens of emails including messages sent to Mr Coulson while he was still an employee of Rupert Murdoch, according to reports. It was described by sources as containing “embarrassing” exchanges with the potential to cast further light on Mr Cameron’s relationship with two of Mr Murdoch’s most senior executives. However, Downing Street was said to have been advised that it was not “relevant” to the Leveson inquiry as the documents they contained fell outside its remit, according to The Independent.

Information imbalances, for us on a more daily basis, have a direct effect on the consumer-supplier relationship of the econy, We have been told to absurdity on how much of our problems as consumers would be solved if we could simply ‘switch easily’ between energy suppliers. In a sense, either there should be far less competition (i.e. the whole thing merges into one state supplier, reducing absurdities in a few suppliers all providing the same product at a high price, similar to exam boards currently), or there should be far more competition (there is currently an oligopolistic situation in many markets, which would be greatly ameliorated by having many more active participants in the competition market.) In 2009, the four largest banks supplied 67% of the market of mortgages, and, in 2006, the ‘big four’ banks accounted for 47% of the market. According to the “Cruickshank review”, the ‘big four’ banks accounted for 17% of the market. Demutualised building societies held 48%: these are, (a) Lloyds TSB, Halifax and Bank of Scotland; (b) Royal Bank of Scotland, Natwest; (c) HSBC, First Direct; (d) Abbey, Alliance and Leicester, Bradford and Bingley.

The Competition Commission believes that helping customers to easily switch products is paramount to the effective operation of competitive markets: markets do not function without customers who vote with their feet. As Dr Adam Marshall of the British Chambers of Commerce told the Commission: ‘There’s lots of products and services on the market, but the theoretical competition between those products and services is limited by the real world barriers of form filling, hassle, bureaucracy, decisions not being taken, etc…’ The regulator responsible for consumer protection regulation should have both: (a) an explicit mandate to promote effective competition in markets in the financial sector; and (b) the necessary powers to regulate the sector to achieve this, including the ability to apply specific licence conditions to banks and exercise competition and consumer protection legislation. These powers will be concurrent with the competition powers of the OFT, and will enable the regulator to both enforce competition law and make market investigation references to the Competition Commission.

The aim of consumer protection regulation is to promote the conditions under which effective competition can flourish as far as possible, and where not, the regulator will be able to take direct action. In order best to promote the interests of the consumer, the regulator will encourage financial firms to compete: on the merit of the quality and price of their products and services; and to gain a competitive advantage by investment in innovation, technology, operational efficiency, superior products, superior service, due diligence, human capital, and offering better information to customers. Ideally, the regulator would then step in whenever there is a sign of market failure. Market failures include: (a) poor quality information being disclosed to consumers when they are deciding whether to purchase products; (b) information asymmetry between the provider and the consumer; or (c) providers taking advantage of typical consumer behaviour such as the tendency evident in retail customers to select the default option offered, and reluctance to switch products because of inertia. Any sign of market failure indicates that competition is probably not effective, and the regulator should then take action to counteract the failure.

Therefore, it is hard to see how information imbalances are not at the heart of many ‘decisions’ affecting modern life, and can lead to imperfect decisions being made. Ideally, it is up to parties to make a full disclosure about things, whether this includes personal health or corporate misfeasance; if they are not so willing to give up their secrets, they possibly can be ‘nudged’ into doing so. Of course, some parties, particularly those intending to generate a healthy shareholder dividend, may not be very keen at all at spilling the beans, and that is where law and regulation come in. However, even then there can be significant imbalances in the legal process which can be obstructive in the correct solutions being arrived at. Certainly the field has progressed substantially since this Nobel Prize for Economics was first awarded over 30 years ago.

Monitor and the regulation of pricing in the NHS

Monitor is in its infancy, but, pardon the pun, I would like to describe an example of childbirth to explain the mountain of problems that the new privatised NHS is yet to experience. Consider this a steep learning-curve that not many of us voted for at the last election.

“The new NHS provider licence: consultation document” was issued by Monitor on 31 July 2012 with a deadline for responses determined as 23 October 2012. According to section 5.1 of this Document on pricing,

“One of Monitor’s new functions will be to set prices for health care services funded by the NHS.Accurate pricing is essential to ensure that providers are paid appropriately for services they provide to patients. Accurate pricing information helps GPs, commissioners and providers to plan and budget for health care services to meet people’s needs. Pricing can also be used to encourage providers to improve the quality of services for patients, and to increase the efficiency with which services are provided. If providers are not properly reimbursed, this can reduce the quality and efficiency of care they offer and may, in some circumstances, threaten the sustainability of their services.”

Pricing is pivotal in markets, and will obviously therefore be expected to the subject of considerable scrutiny by competition regulatory authorities. In future, Monitor will be responsible, in partnership with the NHS Commissioning Board, for setting prices for NHS services. Indeed, according to a statement produced on 20 June 2012,

“The Health and Social Care Act 2012 makes changes to the way health care is regulated in order to strengthen the way patients’ interests are promoted and protected. Monitor’s role will change significantly as we take on a number of new responsibilities. We will become the sector regulator for health care, which means that we will regulate all providers of NHS-funded services in England, except those that are exempt under secondary legislation.”

Take for example the cost to the taxpayer of a provider delivering a baby – not the antenatal or postnatal packages, but the cost of the actual labour and peri-partum process (“the package”). Like any other “product” in the market, a supplier will have to price its product carefully, to ensure that it offers a competitive price, but especially to ensure it does not price itself out of the market by being too costly. The price of “the package” might be determined through a number of different ways.

- Premium pricing (also called prestige pricing) is the strategy of consistently pricing at, or near, the high end of the possible price range to help attract status-conscious consumers. People might buy a premium priced product because they believe the high price is an indication of good quality.

- Cost-plus pricing is the simplest pricing method. The firm calculates the cost of producing the product and adds on a percentage (profit) to that price to give the selling price. This method although simple has two flaws; it takes no account of demand and there is no way of determining if potential customers will purchase the product at the calculated price. You only need to consider the complexity of doing the calculation for the package”, e.g. will the provider use cheap epipdural needs for the anaesthesia, will a foundation year doctor (who is cheaper) perform most of the medicine compared to a specialist registrar (who is more expensive, but more experienced, especially in dealing with medical emergencies).

- Value-based pricing – a price based on the value the product has for the customer and not on its costs of production or any other factor. The relevant issue is how much would you be prepared to have provider A deliver your baby? This is a subjective issue, not easy to predict.

The problem with premium pricing is that providers can collude lawfully to set their prices as high as possible between them. Price fixing is illegal under Article 101 TFEU of the European Union:

Article 101

(ex Article 81 TEC)

1. The following shall be prohibited as incompatible with the internal market: all agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices which may affect trade between Member States and which have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the internal market, and in particular those which:

(a) directly or indirectly fix purchase or selling prices or any other trading conditions;

(b) limit or control production, markets, technical development, or investment;

(c) share markets or sources of supply;

(d) apply dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions with other trading parties, thereby placing them at a competitive disadvantage;

(e) make the conclusion of contracts subject to acceptance by the other parties of supplementary obligations which, by their nature or according to commercial usage, have no connection with the subject of such contracts.

2. Any agreements or decisions prohibited pursuant to this Article shall be automatically void.

3. The provisions of paragraph 1 may, however, be declared inapplicable in the case of:

– any agreement or category of agreements between undertakings,

– any decision or category of decisions by associations of undertakings,

– any concerted practice or category of concerted practices,

which contributes to improving the production or distribution of goods or to promoting technical or economic progress, while allowing consumers a fair share of the resulting benefit, and which does not:

(a) impose on the undertakings concerned restrictions which are not indispensable to the attainment of these objectives;

(b) afford such undertakings the possibility of eliminating competition in respect of a substantial part of the products in question.

It has been incredibly hard to prove price-fixing, but numerous examples exist.

For example, the Daily Mail recently reported price-fixing at the petrol pumps:

“Motorists are being ripped off by profiteering oil companies and speculators, MPs suggested yesterday.They demanded an inquiry into allegations of price-fixing at the pumps, and called for the Government to replace its planned fuel duty rise with a windfall tax on oil company profits.

And last year they reported on the price-fixing of milk:

“Supermarkets and dairy firms have been fined almost £50million over price rigging on milk and cheese that cost families £270million. The collusion put up the price of milk by 2p a litre – 1.2p a pint – and added 10p to the cost of a 500g block of cheese. The punishment was announced by the Office of Fair Trading, following an investigation triggered by whistle blowers at the Arla dairy company. First revealed by the OFT in 2007, the ‘Great Milk Robbery’ took place in 2002 and 2003. But only now has a fine of £49.51million been handed down.”

For Monitor, regulating this will be a mammoth task. Private health providers have much scope for setting between them the most profitable way of delivering the patient’s baby, and it is a great market to be in: the country will never be short of a need for providers of safe deliveries of babies. Whilst other metrics might be important to the clinician, such as mortality or morbidity (infection rates), it could be that private providers are distinguished most themselves by the least cost to a GP practice. Or, it could be that people are genuinely fickle about not caring about who picks up the tab, but the preferred private provider might provide “extra frills”, like en-suite TV with 80 channels.

The problematic issue is what happens if an unconventional problem comes out-of-the-blue. The mother might experience a rare type of headache, such as trigeminal autonomic neuralgia (“TAN”), and there is effectively no “patient choice” involved, save for the GP having to refer the patient to a specialist unit like Great Ormond Street Hospital (“GOSH”). You will notice here that the quality of patient choice is nothing to do with the innovation of the private health provider (can a private provider suddenly make the five stages of labour turn into a more profitable six?), nor indeed how “competitive” the market of private providers of childbirth is (can we get down the speed of the first one from an average of 48 mins to 44 mins?). It is, however, entirely to do with the skill of the clinician in making a rare diagnosis, and having the astuteness of having a specialist unit such as Great Ormond Street Hospital deal with it safely, whatever the cost. You must note that I give this example of TAN at GOSH completely at random, and any similarity to a real-life scenario is of course completely unintentional.

British Gas and oligopolies – the need for regulation and lessons for the privatised NHS

THIS ARTICLE WAS UPDATED ON 13 APRIL 2013

The “fast-buck society”, epitomised by the quick-to-fire Beecroft proposals of employment which is currently unlawful under both domestic and European law, does not respect people in society – it only respects shareholder dividend. Companies are in it for the short-term; therefore any strategy they have is to generate profit in the short-term, indeed a legal obligation of theirs. Unions protect workers, and we virtually agree that it’s essential that workers in society must have protection. The situation regarding privatised utilities is an excellent example of the failure of the markets, and 20 years later history could be repeating itself with our NHS.

Privatisation only works if there is effective regulation of the market, given that the market is so imperfect. The end-result was the production of a few entities in a crowded marketplace, offering effectively no competition and no choice for the customer. Meanwhile, some people did extremely well out-of-it; these are the same people who have benefited from the top band tax cut by George Osborne’s abysmally executed budget.

British Gas this morning faced criticism over alleged profiteering, amid City predictions that the company will reveal this week that it made £100m in extra profits in the first six months of the year. The parent of British Gas, Centrica, reports first-half figures on Thursday. City analysts are now expecting the residential energy supply arm of Centrica, which trades as British Gas, to unveil first- half profits up 25% at £355m as part of a wider Centrica group profit of £1.4bn. Centrica is thought to defend soaring profits by pointing out it reduced its residential electricity prices earlier this year by 5%. Bain has successfully argued that those least able to pay bills are genuinely confused by complex tariffs, and believed that current attempts by the government and industry regulator Ofgem to tackle these problems are insufficient.

The precise accusation is that such companies have been profiteering which comes at the expense of the poor, vulnerable and elderly. Consumer Focus, the government-backed consumer watchdog, said households were facing historically high energy bills, and had long held suspicions that domestic power pricing was not fair. From a regulatory point of view, this has been nothing short of a disaster from the customer’s perspective. The City is encouraging investors to buy Centrica shares and believes that the chances of Ofgem taking a tougher stance against the ‘Big Six; is increasingly unlikely.

The ‘Big Six’ form an “oligopoly”, a common market form. Oligopolistic competition can give rise to a wide range of different outcomes. In some situations, the firms may employ restrictive trade practices such as collusion to raise prices and restrict production in much the same way as a monopoly. Any formal agreement or concerted practice would be unlawful, and be caught by the Competition Act. Firms often collude in an attempt to stabilise unstable markets, so as to reduce the risks inherent in these markets for investment and product development. There does not have to be a formal agreement for collusion to take place (although for the act to be illegal there must be actual communication between companies) – for example, in some industries there may be an acknowledged market leader which informally sets prices to which other producers respond, known as “price leadership”.

What has not happened in this market, unfortunately for the customer, is a situation of competition between sellers in an oligopoly which can be fierce, with relatively low prices and high production. This could lead to an efficient outcome approaching “perfect competition”. In a normal market, it is supply and demand that mostly affect price. Should a consumer find a similar product offered by another provider at a cheaper price, he will make his purchase from that other provider. Suppliers will not, therefore, over-inflate their prices because they will simply lose customers. In an oligopoly, there is little choice for consumers and this will negate any influence they may have had over price control.

The “Big Six” show all the hallmarks an oligopoly. There is literally a ‘handful’ pf sellers. An oligopoly maximises profits by a number of measures. Oligopolies are price setters rather than price takers Barriers to entry from new competitors, are high The most important barriers are economies of scale, patents, access to expensive and complex technology, and strategic actions by incumbent firms designed to discourage or destroy new firms. Additional sources of barriers to entry often result from government regulation favoring existing firms making it difficult for new firms to enter the market. The sellers are all selling the same thing (e.g. gas, water) – i.e. it’s a heterogeneous undifferentiated market. The distinctive feature of an oligopoly is interdependence. Oligopolies are typically composed of a few large firms. Each firm is so large that its actions affect market conditions. Therefore the competing firms will be aware of a firm’s market actions and will respond appropriately. This means that in contemplating a market action, a firm must take into consideration the possible reactions of all competing firms and their reactions.

Left to its own devices, it is hard to see how end-users (or customers) can benefit from this imperfect competition. That is why the law must step in, and one of the ways in which it can do this is taxation of the utility companies. Due to the dire state of the public finances, made massively worse by this current Government, this might be a reasonable next step.

David Bennett has recently indicated that a “spoonful” of competition will help the NHS. But this is precisely the point – a ‘spoonful’ will produce an oligopoly, where a lot of profit is returned to the shareholder and incumbent directors, but not much value is returned to the customer. If the NHS fails to attract many entrants because the significant risks in a sustainable business and financial strategy, exactly the same situation will result from private providers doing a bulk of NHS work. This will end up costing the NHS substantially more in the long-term, and makes a fragmented, non-universal service much more likely. Even Richard Branson opined on LBC this week, on Margaret Thatcher’s death, that he wishes that he had seen more competition in the airlines industry; this, from the perspective of the end-user, is exactly why.

Sexy regulation and the City

This is an extremely issue. My title belies the fact that I strongly feel that the City builds competitive advantage by not only complying with the law, but also acting strategically to use the law to outperform international competitors. It simply can’t be understood through the psychodrama spectacles of Osborne, Brown or Balls.

There has been a general undercurrent that the City’s “competitive advantage” comes from the unique way in which the City has a ‘light touch on regulation’. Fraud, which has gone unnoticed in Barclays, is still undoubtedly a criminal offence, and it is simply no sympathy for, as far as the English law is concerned, that Bob Diamond was unaware of criminal activity prior to the formal investigations. Financial regulation, which has been enforced latterly in a number of successes for the Financial Services Authority, has had a most unclear place in ascertaining how the Bank of England (and other central banks) have had an effect on LIBOR.

I have no doubt that George Osborne will want to send out a powerful signal (including to corporate investors internationally) that London is competent on regulation. The ideological desire to cut red-tape should not inadvertently be allowed to become a ‘Criminal’s Charter’ in the City of London. Nick Cohen has elegantly referred to it in a brilliant article entitled ‘Crony Capitalism’, thus:

“Today’s hypocrisies cannot last for two reasons. First the gap between what Conservatives say and what they do will soon become an electoral liability. No centre-right party can expect to prosper if it puts the interests of the state-subsidised rich before the interests of the middle class. Second, inertia is destroying what’s left of the City’s reputation. Unless radical reform begins soon, the world will see it as a pirate state which you visit, rob or be robbed but never to conduct honest business.”

On February 23rd 2006, George Osborne wrote about how wonderful the Irish economy was, how we could all learn lessons from it, before it went bust. This is concluding paragraph of that famous article in the Times by George Osborne:

“The new global economy poses real long-term challenges to Britain, but also real opportunities for us to prosper and succeed. In Ireland they understand this. They have freed their markets, developed the skills of their workforce, encouraged enterprise and innovation and created a dynamic economy. They have much to teach us, if only we are willing to learn.“

This is analysed, albeit with a retrospectoscope, as follows in the Financial Times:

“Poor regulation wasn’t a problem identified by Osborne at the time. Indeed, he thought Brown had some lessons to learn from the Irish light touch. He warned that Britain was “falling behind” Ireland: “Poor skill levels, rising taxes, bureaucratic planning controls and chronic overregulation are high on the list of culprits.”

The contribution of this deregulation to the Irish economy ‘bust’ has been well documented. Here’s an extract ironically from their report on the banking crisis:

“It appears clear, however, that bank governance and risk management were weak – in some cases disastrously so. This contributed to the crisis through several channels. Credit risk controls failed to prevent severe concentrations in lending on property – including notably on commercial property – as well as high exposures to individual borrowers and a serious overdependence on wholesale funding. It appears that internal procedures were overridden, sometimes systematically. The systemic impact of the governance issues crystallised dramatically with the Government statements that accompanied the nationalisation of Anglo Irish Bank. Some governance events are already under investigation. There is a need to probe more widely the scope of governance failings in banks, whether they were of a rather general kind or (apparently in far fewer instances) connected with very serious specific lapses, and whether auditors were sufficiently vigilant in some episodes.”

Finally, this is the article here which I am produced for ‘public interest’ given that George Osborne is currently the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Unfortunately, it has been deleted off the Times website which is most unusual given that the Times archive is otherwise complete and reliable; it also has been recorded for posterity here. The existence of this article on February 23rd 2006 is well evidenced in these articles (example 1, example 2,example 3, example 4).

“A generation ago, the very idea that a British politician would go to Ireland to see how to run an economy would have been laughable. The Irish Republic was seen as Britain’s poor and troubled country cousin, a rural backwater on the edge of Europe. Today things are different. Ireland stands as a shining example of the art of the possible in long-term economic policymaking, and that is why I am in Dublin: to listen and to learn.After centuries of lower incomes, Irish average incomes are now 20 per cent higher than in the UK. After being held back for decades, the productivity of Irish companies — the yardstick of economic performance — has grown three times as quickly as ours over the past ten years. Young Irish families once emigrated in their millions to seek a better life overseas; these days it is young people across Europe who come to Ireland to find good jobs. Dublin’s main evening newspaper even carries a Polish-language supplement.

Ireland is no longer on the edge of Europe but is instead an Atlantic bridge. High-tech companies such as Intel, Oracle and Apple have chosen to base their European operations there. I will be asking Google executives today why they set up in Dublin, not London. It is the kind of question I wish the Chancellor of the Exchequer was asking.

What has caused this Irish miracle, and how can we in Britain emulate it?Three lessons stand out. First, Ireland’s education system is world-class. On various different rankings it is placed either third or fourth in the world. By contrast, Britain is ranked 33rd and our poor education performance is repeatedly identified by organisations such as the OECD as our greatest weakness. It is not difficult to see why. Staying ahead in a global economy will mean staying at the cutting edge of technological innovation, and using that to boost our productivity. To do that you need the best-educated workforce possible. It is telling that even limited education reform is proving such a struggle for the Prime Minister.

Secondly, the Irish understand that staying ahead in innovation requires world class research and development. Using the best R&D, businesses can grow and make the most of the huge opportunities that exist in the world. That is why it is shocking that the level of R&D spending actually fell in Britain last year. Ireland’s intellectual property laws give incentives for companies to innovate, and the tax system gives huge incentives to turn R&D into the finished article. No tax is paid on revenue from intellectual property where the underlying R&D work was carried out in Ireland. While the Treasury here fiddles with its complex R&D tax credit system, I want to examine whether we could not adopt elements of Ireland’s simple and effective approach.

Thirdly, in a world where cheap, rapid communication means that investment decisions are made on a global basis, capital will go wherever investment is most attractive. Ireland’s business tax rates are only 12.5 per cent, while Britain’s are becoming among the highest in the developed world.

Economic stability must come before promises of tax cuts. If, over time, you reduce the share of national income taken by the State, then you can share the proceeds of growth between investment in public services and sustainably lower taxes. In Britain, the Left have us stuck debating a false choice. They suggest you have to choose between lower taxes and public services. Yet in Ireland they have doubled spending on public services in the past decade while reducing taxes and shrinking the State’s share of national income. So not only does Ireland now have lower business and income taxes than the UK, there are also twice as many hospital beds per head of population.

World-class education, high rates of innovation and an attractive climate for investment: these are all elements that have helped to raise productivity in Ireland. It is not the only advanced economy to have achieved this uplift. Last week in Washington the new Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, told me about the impact that the sustained increase in productivity growth had made in generating prosperity in the US. By contrast, in Britain productivity growth has fallen in recent years and is far behind the likes of the US and Ireland. Indeed, it is one fifth the rate it was when Gordon Brown walked into the Treasury. Poor skill levels, rising taxes, bureaucratic planning controls and chronic overregulation are high on the list of culprits. Britain is being left behind.

Faced with the extraordinary rise of economies such as China, India and Brazil, many European governments seem to have accepted that long-term decline is inevitable. I detect a similar pessimism here. How on earth, people ask, will we ever compete in such a fiercely competitive world? The Chancellor’s answer is to put up the shutters and stick on a path of ever-higher taxation and an ever-growing State. But you cannot shut out the future.

The new global economy poses real long-term challenges to Britain, but also real opportunities for us to prosper and succeed. In Ireland they understand this. They have freed their markets, developed the skills of their workforce, encouraged enterprise and innovation and created a dynamic economy. They have much to teach us, if only we are willing to learn.”

Even if there is no judicial-led inquiry, we need to learn lessons about the importance of regulation and the City.