Home » Posts tagged 'markets'

Tag Archives: markets

The NHS needs an innovative ‘blockbuster’ now. That is to be brought back under the State.

The term “innovation” must be one of the most misused terms in the media. It simply means a different way of doing things, such as a product or a service, whose popularity and effectiveness ultimately govern its success.

And yet the term has been strikingly bastardised to be used in conjunction with a whole plethora of memes such as “ageing”, “technology” and “unsustainable”. The right wing has been consistently ‘on message’ in this script.

Ed Miliband in Manchester gave last night what was a perfectly plausible speech on the NHS last night. Excerpts of it have indeed been posted on our blog. And there was the usual ‘red meat’, to be accompanied at some later date by how realistic the costings are.

But the legitimate concern of voters, whether hardworking or not, is he who pays the piper calls the tune. It may not be the frontline staff with whom Ed Miliband had photo opportunities earlier this week.

Fifty shades of government, apart from green, have been obsessed with inflicting ‘transformative’ changes, perhaps ‘charismatic’ visions, without ever consulting the wider population. Examples include the private finance initiative, or ratcheting up the NHS into a competitive market.

But Nigel Farage, whether or not he is ‘establishment’, has struck a chord with some voters. I don’t mean with his allegedly racist twangs, but I mean his ‘trust the voter’ skit. He bangs on about the referendum which he knows will never see the light of day.

Labour’s argument for why the NHS needs private companies working for it remains unconvincing with many voters. That’s why the National Health Action Party or the Green Party are watched so keenly by many.

The argument is possibly not as complicated as that justifying our membership of the European Union, but it is one which is best left to the voters to justify.

Labour in pursuing its ‘35% strategy’, where it can squeeze into office on the back of disaffected Liberal Democrat voters, is by definition risk averse. But with taking low risks the return can be very low. Labour’s lack of “blockbuster” is potentially alarming.

And many of the arguments can be discussed under the assumption that GPs work for the NHS. The BMA’s “#YourGPcares” campaign is calling for long-term, sustainable investment in general practice now to attract, retain and expand the number of GP, expand the number of practice staff, and improve premises that GP services are provided from.

The pitch for state ownership is pretty basic. Ed Miliband MP, Leader of the Labour Party, yesterday Labour’s new GP guarantee as part of the next government’s plan to improve services for patients, ease the pressure on hospitals, and restore the right values to the heart of the NHS.

Speaking in Manchester, he underlined his determination to put the health service at the centre of Labour’s campaign over the next year, beginning with these local and European elections.

But it feels as if Ed Miliband is making a meal lacking the key ingredients.

Andy Burnham MP’s ‘NHS preferred provider’ is conspicuous by its absence in the speech.

Only once Ed Miliband has slain this dragon, he can be given to talk about how primary care is best delivered. Labour is aware of its history of “polyclinics” first proposed by Professor the Lord Darzi of Denham in his review of healthcare in London for NHS London “Healthcare for London: A Framework for Action”.

The Labour Government at the time argued that this was a way of providing more services in the community closer to home and at more convenient times (including antenatal and postnatal care, healthy living information, community mental health services, community care, and social care and specialist advice).

Ed Miliband seems to care about ‘privatisation of the NHS’, in that he cared to mention ‘ending’ it.

But this is again at odds with what Simon Stevens has been thinking about.

A “Free School” is a type of Academy, a State-funded school, which is free to attend, but which is not controlled by a Local Authority.

Like other types of academy, Free Schools are governed by non-profit charitable trusts that sign funding agreements with the Secretary of State.

Supporters of Free Schools, such as the Conservative Party, including that they will “create more local competition and drive-up standards” They also feel they will allow parents to have more choice in the type of education their child receives, much like parents who send their children to independent schools do.

But Ed Miliband also talking about ‘ending competition’ which is somewhat against the mood music Simon Stevens was singing in his appearance against the Commons Select Committee.

It’s innovative bringing something back into state control, but could make good ‘business sense’, akin to insourcing a service which had been previously outsourced.

The main arguments for state control and ownership of the NHS are that such a drive would encourage co-operation, collaboration, equity; services could be properly planned not fragmented; and services would not be run for shareholder dividends.

It’s undoubtedly true that there could be operational changes to be made, such that patients could plan their GP appointments without having to ring up as an emergency at 8.30am the same day.

NHS GPs overall say that they are working flat out, and, short of having greater resources, no political gimmick will help them. Instead of lame slogans such as “Hardworking Britain Better Off”, and making do with “35%”, Labour could do something really innovative – and return to a socialist approach.

‘Saving the NHS for the public good’, on the other hand, is not a vacuous gimmick. It’s what many people in Labour also believe, possibly. More importantly, it’s the title of a current party election brodcast by the Green Party. It might be the case that Ed Miliband is left wing than the Labour Party membership. This has been mooted here. If so, “bring it on!”

Would knowing your genetic risk for dementia change the way you behave with the NHS?

Background

Various funding mechanisms for long-term care for dementia have come under scrutiny, including private insurance, drawing on the experience of various jurisdictions (e.g. Hayashi, 2013).

An insurance contract is a contract whereby, for specified consideration, one party undertakes to compensate the other for a loss relating to a particular subject as a result of the occurrence of designated hazards.

The normal activities of daily life carry the risk of enormous financial loss. Many persons are willing to pay a small amount for protection against certain risks because that protection provides valuable peace of mind.

The term insurance describes any measure taken for protection against risks.

In an insurance contract, one party, the insured, pays a specified amount of money, called a premium, to another party, the insurer. The insurer, in turn, agrees to compensate the insured for specific future losses. The losses covered are listed in the contract, and the contract is called a policy.

You can often have more information than the person with whom you enter into a transaction – or vice versa. This is a potent phenomenon called “information asymmetry”.

Following the seminal work by Arrow (1963), the notion of information asymmetry have by now been recognised as a cornerstone of modern insurance theory.

George Akerlof was the the author of a landmark study on the role of asymmetric information in the market for “lemon” used cars.

His research broke with established economic theory in illustrating how markets malfunction when buyers and sellers — as seen in used car markets — operate under different information.

This seminal work has had far-reaching applications in such diverse areas as health insurance, financial markets and employment contracts. It could now impact on the way the National Health Service acts in the future in implementation of “needs based commissioning“.

Health economists, not least Prof Julian LeGrand of the LSE, in the frenzy of New Labour and subsequent English administrations have been hell bent on introducing a ‘market’ into the NHS. And this introduction of the market or ‘quasi-market’ has had a profound impact on resources and planning, as well as large charities.

According to numerous news reports, a global study involving more than one million people to look at the influence of genetics and lifestyle in Azheimer’s disease will be led by scientists from Cardiff University.

The £6m project will combine the power of multiple studies from around the world to explore the roles of genes and lifestyle choices to produce the most comprehensive understanding of the disease’s risk to-date.

Information gathered by researchers from across the globe will provide scientists with the best evidence yet for creating a fuller picture of why the disease develops and the degrees of risk it poses to different individuals.

This study clearly has implications for the future.

Sir David Nicholson spotted these implications at once.

@legalaware this coupled with data coming from genetics means that whole pop risk pools supported by tax funded systems is the future

— David Nicholson (@DavidNichols0n) April 3, 2014

And in fairness David‘s starting point is fundamentally one of universality.

CCGs, or clinical commissioning groups, do not particularly need to be manned by clinicians, though that it is how the concept has continued to be marketed to the public and GPs. They are simply state-run populations pooling risk, and there has never been any precise guidance on their exact size (in terms of number of people in each catchment).

Aim

With such recent upheavals in health policy in England, with discussion of an insidious ‘privatisation agenda’, this online survey was undertaken with a view to working out whether members of a general public exhibited views with the functioning of private insurance markets.

Methods

I completed a study. Respondents were invited from my Twitter account @legalaware with close to 12000 followers.

I used ‘SurveyMonkey’ to carry out this survey. With ‘SurveyMonkey’, you cannot complete the survey more than once.

There were 125 respondents in total.

The sample is possibly biased, in that I have a predominantly left-wing follower list consisting of about 11000 followers of mainly well-informed people.

Exclusions

None.

Results

However, in fairness, it is worth noting that certain key policy planks have cross-party support, including free-at-the-point-of-need and personal budgets.

A rebuttable assumption of universality

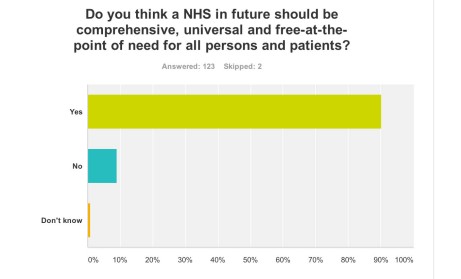

In answer to “Do you think a NHS in future should be comprehensive, universal and free-at-the-point of need for all persons and patients?”, 99% answered yes (n = 123). The problem with this is that opinions about the extent to which the NHS offers a comprehensive service is qualified by some degree of ‘rationing‘ already.

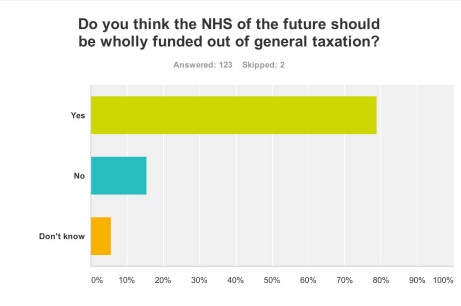

However, I did ask “Do you think the NHS of the future should be wholly funded out of general taxation?”. I used the word ‘wholly’ meaning completely. Despite this high threshold, 79% said ‘yes’ (n = 126).

The NHS provides the majority of healthcare in England, including primary care, in-patient care, and long-term conditions. The National Health Service Act 1946 came into effect on 5 July 1948. Private health care has continued parallel to the NHS, paid for largely by private insurance, but it is used by less than 8% of the population, and generally as a top-up to NHS services.

Attitudes in my survey are interesting in light of extensive media coverage for Lord Warner’s plan for a £10 top-up fee to be paid through council tax. This is further interesting as it shows a desire to avoid a private insurance-based system in the future. But others have argued including Caroline Molloy and Bob Hudson that it’s a “zombie policy”.

A number of various solutions to the NHS “funding gap” continue to be produced – see for example Wilby (2004) here in the Guardian:

Data sharing of genetic risk within the NHS

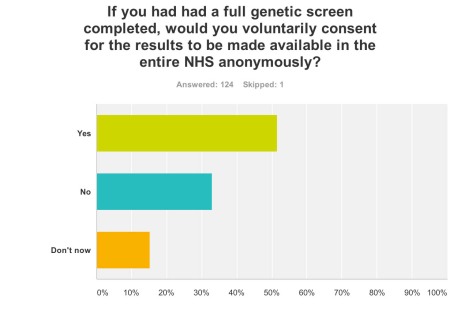

I also asked, “If you had had a full genetic screen completed, would you voluntarily consent for the results to be made available in the entire NHS anonymously?” This produced a very mixed response: yes – 52%, no – 33%, don’t know – 16% (n = 124).

This is interesting in light of the ‘case finding’ approach in England, where a possible diagnosis of dementia might be chased up even if not initiated by the person directly involved, exacerbated perhaps in the drive from politicians and the Alzheimer’s Society for improved diagnosis rates.

Such a policy clearly is problematic in terms of valid consent ethically. Notwithstanding the general issue comes up as to whether an individual should disclose the possible diagnosis of a dementia beyond even the confidential jurisdiction of his or her Doctor, and to share the information with the State. But this is the same problem which led Care Data to run into difficulties.

It could be that the recent furore over care data, through the subject being badly managed by NHS England with the general public, may have impacted on this general lack of willingness of a member of a general public to share details of a genetic screen with the NHS at large.

Single unified budgets

A consistent policy strand of late has been the desire to introduce personal budgets for dementia (and this is across all main political parties).

The concept of a single unified budget has now come up consistently in various arenas: namely, the Fabian Society document on whole person care, the IPPR review of whole person care, and the Barker Commission of the King’s Fund last week.

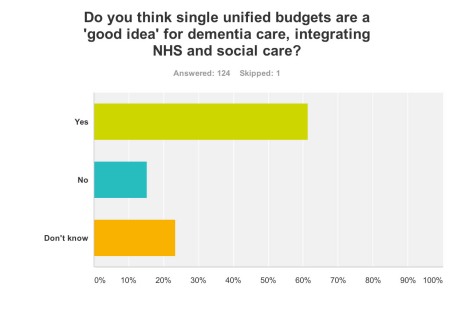

I asked, “Do you think single unified budgets are a ‘good idea’ for dementia care, integrating NHS and social care?”, and it is noteworthy that the majority (61%) said yes, with only 15% saying no. The proportion saying they don’t know (23%) constitutes, though, a sizeable minority (n = 124).

Taken with the above finding with the general popularity of universality, one might infer that people generally don’t want to see single unified budgets as a backdoor mechanism of introducing care for which you have to pay extra.

The uncertainty for this is indeed interesting.

The recent interim report from the King’s Fund “Barker Commission” (2014) on the future of health and social care made the following observation:

“If they become widely adopted, it is difficult to see how anyone could be prevented from topping them up – that is, buying additional health care privately that goes beyond the agreed package.”

Nonetheless the notion of a ‘shared budget’ continues to gain traction. McNeil and Hunter (2014) in their recent IPPR report comment:

“More third-party organisations, such as community groups, faith organisations, mutual support groups and micro-enterprises should be invited to take on responsibility for developing packages of care and support for individuals in this way if they meet certain core criteria.”

And so – therein lies the crunch. The devil lies in the detail?

Information asymmetry and markets

Profiling someone’s risk is exactly how private insurance markets work.

They process your dividend according to your risk. There are concerns that the NHS is heading towards a private insurance system, if only to be integrated fully with one.

Moral hazard

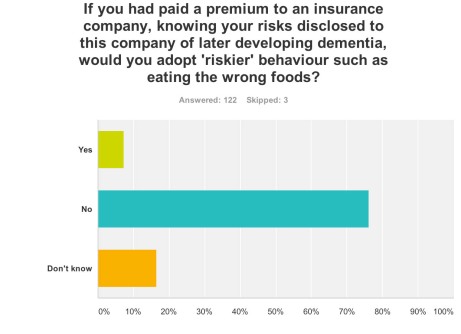

The question “If you had paid a premium to an insurance company, knowing your risks disclosed to this company of later developing dementia, would you adopt ‘riskier’ behaviour such as eating the wrong foods?” produced a very interesting observation.

This is “moral hazard”.

In economic theory, a moral hazard is a situation where a party will have a tendency to take risks because the costs that could result will not be felt by the party taking the risk. In other words, it is a tendency to be more willing to take a risk, knowing that the potential costs or burdens of taking such risk will be borne, in whole or in part, by others. A moral hazard may occur where the actions of one party may change to the detriment of another after a financial transaction has taken place.

7% said yes, but 76% said no (17% said don’t know) (n = 122).

This for me demonstrates that the general population in this scenario does not behave like a typical insurance market for goods, and this could be something to do with a person will not wish to take risks with their personal health irrespective of the scientific evidence.

And in fairness, a genetic risk for dementia might not be nearly as important as environmental factors for someone developing a dementia, and people are reluctant to take risks with that.

Adverse selection

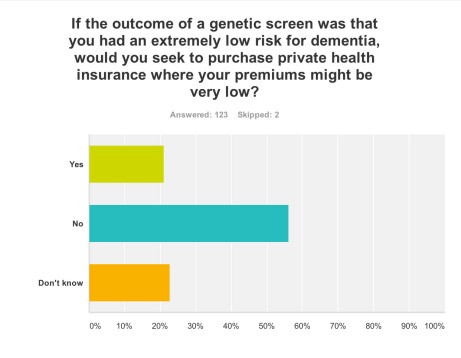

I asked, “If the outcome of a genetic screen was that you had an extremely low risk for dementia, would you seek to purchase private health insurance where your premiums might be very low?” Amazingly, despite 21% of respondents saying yes, 56% said no and 23% said they didn’t know (n = 123).

This is “adverse selection”.

The term adverse selection was originally used in insurance. It describes a situation wherein an individual’s demand for insurance (the propensity to buy insurance and the quantity purchased) is positively correlated with the individual’s risk of loss (higher risks buy more insurance), and the insurer is unable to allow for this correlation in the price of insurance.

Limitations

All respondents were in the UK.

There might have been political bias in the sample, though it is useful to note perhaps that personal health budgets and a comprehensive universal NHS, free at the point of need, have currently cross-party support.

Conclusion

Clearly a much larger sample is going to have to ascertain what these trends are.

There is no doubt that the furore over care data sharing and the policy to improve diagnosis of dementia rates will have a legacy on future dementia policy, and possibly a very negative one.

And finally, evidence from moral hazard and adverse election demonstrate that individuals assessing their risk for dementia may not behave like traditional insurance markets.

Reasons for this might include the facts that adults in fact prioritise their own health and do not wish knowingly to put it to risk, they appreciate the rôle of factors in the environment which could throw havoc for insurers’ calculations, and that they have a deep-felt genuine ‘brand loyalty’ and affection for ‘that national religion’, the NHS.

This is reflected in the following graphic tweeted recently.

The negative publicity surrounding the Health and Social Care Act (2012) as regards privatisation may have played an important rôle here.

This is all very problematic if the ultimate goal for increasing awareness of dementia was to boost the private insurance industry and Big Pharma. It looks as if the NHS might have the last laugh after all.

References

Arrow, Kenneth J. (1963) “Uncertainty and the Welfare Economics of Medical Care”, American Economic Review 53 (5), pp. 941–973

Hayashi, Mayumi (2013) The lessons Japan has for the UK on dementia, The Guardian (link)

McNeil, Clare, Hunter, Jack [for IPPR] (2014) “The generation strain: collective solutions to care in an ageing society”, link here.

Wilby, Peter (2014) The NHS needs a life-saving idea – how about a health tax? The Guardian (link)

Will the catalysmic implosion of the market ideology now move onto the NHS?

This week, David Cameron MP mocked Ed Miliband MP for sounding like a person who’d rung up a radio show whingeing.

Cameron replied, “And your problem is caller?”

The problem is a complete collapse of ideological position which has lasted decades.

Ed Miliband keeps up the moment today with the market failure of the energy oligopoly (see article by Patrick Wintour in the Guardian.)

It is argued that one of the precursors of Thatcherism was a revival of interest in Britain and worldwide in the work of the Austrian economist and political philosopher, Friedrich Hayek, who won the Nobel Prize for economics in 1974.

Alongside Milton Friedman, who won his Nobel Prize in 1976, Hayek lent great prestige to the cause of economic liberalism, helping to create the sense of a rightward shift in the intellectual climate, complementing the approach of Ronald Reagan across the pond.

These principles of dogma have seen successive Conservative and Labour governments reaching for the drug of privatisation and outsourcing.

But these drugs are not only failing to work. They are having devestating side effects which are killing the patient.

The markets have been outed for being far from liberalising. They create inequality. It is alleged that the austerity-based policies have led to a marked decline in mental health and rates of suicide even.

But it’s not the shocking Gas bill which has delivered the knock-out blow for the Conservatives’ religion.

“Here is the reality. This is not a minor policy adjustment—it is an intellectual collapse of the Government’s position.”

This was Ed Miliband’s verdict in Wednesday’s Prime Minister’s Questions.

Only a day previously, BBC Radio 4’s had played a voxpop of various members of the public speaking about ‘payday loans’ as a prelude to interviewing George Osborne MP.

“I don’t accept it’s a departure from any philosophy. The philosophy is we want markets to for people. People who believe in the markets like myself want the market regulated. The next logical step is to cap the cost of credit. It’s working in other countries. In fixing the banks, we need to fix all parts of the banks and the banking system. It helps all hard-working people.”

During the time of the previous Labour government, the King’s Fund was head-over-heels promoting competition.

It was known that, by shoehorning competition as a policy, private providers would make a killing.

All you had to do was to bring in a £3bn ‘top down reorganisation’, a 500 page Act of parliament containing no clause on patient safety apart from the abolition of the National Patient Safety Agency, and beef up a new consumer regulator (“Monitor”).

But meanwhile back to payday lending, an evidenced case of market failure.

“We’ve always believed in properly regulated free markets, where there’s competition, but where the market is properly regulated. That’s why we created a new consumer regulator.”

Far from being a loveable buffoon Boris Johnson, Johnson has revealed himself to be the toxic political mess he is.

Suzanne Moore, at the risk of being hyperbolic, called out Johnson as ‘sinister’.

Johnson had launched this week a bold bid to claim the mantle of Margaret Thatcher by declaring that inequality is essential to fostering “the spirit of envy” and hailed greed as a “valuable spur to economic activity”.

In an attempt to shore up his support on the Tory right, as he positions himself as the natural successor to David Cameron, the London mayor called for the “Gordon Gekkos of London” to display their greed to promote economic growth.

He qualified his unabashed admiration for the “hedge fund kings” by saying they should do more to help poorer people who have suffered a real fall in income in recent years.

And what’s wrong with greed being good if this improves patient care in the NHS?

The issue always remains ‘zero sum gain’. It’s a problem as it diverts tax-funded resources directly in the coffers of the private sector.

Arguably, it’s not just the failure of the market which is the problem, but ‘the undeserving rich’ who have never ‘seen it so good’ since Tony Blair’s New Labour period of government.

In August 2009, the then leader of the Opposition and Conservative leader, David Cameron, MP defended a shadow health minister for advising a firm which offers customers an alternative to NHS doctors.

Lord McColl was on the advisory board of Endeavour Health, which promised a quick and convenient access to a network of “top” private GPs.

It was claimed then that Endeavour Health is a company set up by two hedge fund advisers which purported to be Britain’s first comprehensive private GP network.

In a video yet to be deleted off You Tube, David Cameron argued that there was nothing ‘improper’.

This was interpreted at the time that the Conservatives “favoured private alternatives”.

Nonetheless, David Cameron claimed that the Conservatives was ‘totally dedicated to the NHS’, but he wished ‘to expand the NHS so that people don’t have to use the private sector’.

What actually happened was the Health and Social Care Act (2012).

In July 2013 in the British Medical Journal, it was reported that the private sector is in line to secure hundreds of millions in NHS funding from services placed out to the open market under the UK government’s latest competition regulations, a study has shown.

Research by the pressure group the NHS Support Federation found that contracts for around 100 NHS clinical services totalling almost £1.5bn (€1.7bn; $2.2bn) have been advertised since 1 April 2013, with commercial companies winning the lion’s share of those awarded to date.

Data from official tenders websites showed that only two of 16 contracts awarded since the government’s section 75 regulations of the Health and Social Care Act came into force have gone to NHS providers, with the remaining 14 going to the private sector.

A few days ago, it was reported tonight that David Cameron is intending to ban branded cigarette cartons, having originally decided last July not to proceed with the plans.

In the summer the Government said it was waiting to see how plain packaging worked in Australia, which introduced the measures a year ago, before making any changes. It has since maintained it is monitoring the situation.

That is the spin. Behind the scenes, it is well known that tobacco corporates have throttled public health policy.

In the third volume of Law, Legislation and Liberty, Hayek argued that there are not two but three kinds of human values: those that are “genetically ordered and therefore innate”; those that are “products of rational thought”; and values that had triumphed in the course of cultural evolution by demonstrating their suitability to the successful organization of social life.

Hayek believed that these values were a cultural inheritance, survivors of a competitive struggle, and essential conditions for the successful evolution of our society.

David Cameron is indeed right to be worried.

There has been a collapse of the ideological position that he and his predecessors, Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair, stood for.

This is in relation to the markets.

This fundamentally changes the terms of reference for a market-based NHS.

Contagion is likely politically.

If payday lending or the energy markets are anything to go by, there could be trouble ahead.

So what’s the issue? The caller’s problem is that “the markets don’t work”, “they only make you feel worse again”.

And now the caller’s finally worried about the NHS.

My blog on dementia is here: http://livingwelldementia.org

The "everyday" "stack-em-high" culture clearly doesn't work for all of the NHS

Right-wing commentators always attack the NHS by saying that it mustn’t be treated as a “sacred cow”, like a “national religion”. The public don’t wish to see it as a business either. It is not surprising that the Royal College of Surgeons as a College are in favour of the “reforms” increasing the scope for private provision, but most surgeons were indeed also trained by the NHS.

So, if it’s not a business, why are they such pains to keep the NHS branding and logo then? The lettering (even the font, size, colour and slant) is known on the national trademarks register, so is the exact Pantone colour. Why are Virgin and Circle not keen to get rid of the NHS branding and do all their NHS services in their own brand? This is simple. It’s because the NHS brand is incredibly strong, so much so that successive governments have wished to export it.

Tesco everyday burgers contain “no artificial preservatives, flavours or colours”, except some contained horsemeat apparently. Not being able to see inside the box with the benefit of a DNA reader is possibly to blame, but which corporate supplier is providing your hernia operation in future may not be so easy to tell in future either.

One thing is absolutely certain about the NHS “reforms”. It is most definitely a “top-down reorganisation”, it will not address the numerous concerns of the Francis Report, and it gives a clear green light to outsourcing a far greater number of contracts to private sector suppliers who are very slick at producing bids. Even the most unintelligent of spokespeople for the Conservatives’ policy, both official and unofficial, openly concede that it is hard to provide a service that is comprehensive and bitty through this route.

That’s why it best for the profitability of shareholders that the product is delivered in a short-sharp-shock, like an abdominal hernia repair, or a Tesco “everyday burger” containing horsemeat. They choose what offerings they wish to produce. Whilst the Ed Miliband conference speech on ‘predators and producers’ was on-the-whole “panned”, the new healthcare market is perfect for private equity investors. Their freedom to operate in a “liberalised market” is only constrained by the legal and regulatory constraints placed upon them. You can argue “til the cows come” home whether the abolition of the Foods Standards Authority created a climate for such cutting corners to occur – or maybe that should be “til the horses come home”.

While it’s well known that some high street firms have struggled, it’s noticeable that “value brands”, including Tesco everyday value items and Aldi, and “luxury” brands have withstood the recession quite well. There is of course no real market in healthcare, of people “shopping around”, with a customer not paying directly to the supplier of the healthcare product, the supplier using the NHS branding away, and dodgy metrics to judge the ‘quality’ of a healthcare intervention largely dreamt up by a busybody who has never set foot on a busy NHS ward.

However, that the NHS could offer its equivalent of “value” products, but not to enhance shareholder dividend, but for the benefit of treating as many people as possible efficiently to the highest of rigorous medical and nursing standards is a worthy cause. An unfortunate effect of the reaction to the Tesco “horsemeat” saga is that rather demeaning judgements about people who buy “everyday” products have entered through the back door. However, many people are desperately keen to avoid an emergence of a “two tier” service in healthcare where access-to-medical-treatment becomes dependent upon an ability-to-pay.

It’s possible that at the “everyday” end of the NHS, it might be possible to go for the “stack them high” approach which is pervading education and healthcare, which is perfect for private equity investors. However, this system is clearly not ideal for all, and this is clear not a market led by the “end-consumer”. Characteristics of markets where there is poor competition due to lack of participants include an inability of customers to lower prices and an ability for suppliers to increase prices, while providing the essentially the same product. This is what has happened in a whole string of privatised industries, including gas, electricity, water and railways, and the (relatively) “simple” hernia operation is going to be no different. Whose going to benefit from offering a contracted core NHS service? Of course, the corporates whom I don’t dare to name because of their legal teams. Will the patient benefit compared to a NHS ideal of “comprehensive” and “free-at-the-point-of-use”? Absolutely not.

The “Everyday” “stack-em-high” culture clearly doesn’t work for all of the NHS

Right-wing commentators always attack the NHS by saying that it mustn’t be treated as a “sacred cow”, like a “national religion”. The public don’t wish to see it as a business either. It is not surprising that the Royal College of Surgeons as a College are in favour of the “reforms” increasing the scope for private provision, but most surgeons were indeed also trained by the NHS.

So, if it’s not a business, why are they such pains to keep the NHS branding and logo then? The lettering (even the font, size, colour and slant) is known on the national trademarks register, so is the exact Pantone colour. Why are Virgin and Circle not keen to get rid of the NHS branding and do all their NHS services in their own brand? This is simple. It’s because the NHS brand is incredibly strong, so much so that successive governments have wished to export it.

Tesco everyday burgers contain “no artificial preservatives, flavours or colours”, except some contained horsemeat apparently. Not being able to see inside the box with the benefit of a DNA reader is possibly to blame, but which corporate supplier is providing your hernia operation in future may not be so easy to tell in future either.

One thing is absolutely certain about the NHS “reforms”. It is most definitely a “top-down reorganisation”, it will not address the numerous concerns of the Francis Report, and it gives a clear green light to outsourcing a far greater number of contracts to private sector suppliers who are very slick at producing bids. Even the most unintelligent of spokespeople for the Conservatives’ policy, both official and unofficial, openly concede that it is hard to provide a service that is comprehensive and bitty through this route.

That’s why it best for the profitability of shareholders that the product is delivered in a short-sharp-shock, like an abdominal hernia repair, or a Tesco “everyday burger” containing horsemeat. They choose what offerings they wish to produce. Whilst the Ed Miliband conference speech on ‘predators and producers’ was on-the-whole “panned”, the new healthcare market is perfect for private equity investors. Their freedom to operate in a “liberalised market” is only constrained by the legal and regulatory constraints placed upon them. You can argue “til the cows come” home whether the abolition of the Foods Standards Authority created a climate for such cutting corners to occur – or maybe that should be “til the horses come home”.

While it’s well known that some high street firms have struggled, it’s noticeable that “value brands”, including Tesco everyday value items and Aldi, and “luxury” brands have withstood the recession quite well. There is of course no real market in healthcare, of people “shopping around”, with a customer not paying directly to the supplier of the healthcare product, and the supplier using the NHS branding away, dodgy metrics to judge the ‘quality’ of a healthcare intervention largely dreamt up by a busybody who has never set foot on a busy NHS ward.

However, that the NHS could offer its equivalent of “value” products, but not to enhance shareholder dividend, but for the benefit of treating as many people as possible efficiently to the highest of rigorous medical and nursing standards is a worthy cause. An unfortunate effect of the reaction to the Tesco “horsemeat” saga is that rather demeaning judgements about people who buy “everyday” products have entered through the back door. However, many people are desperately keen to avoid an emergence of a “two tier” service in healthcare where access-to-medical-treatment becomes dependent upon an ability-to-pay.

It’s possible that at the “everyday” end of the NHS, it might be possible to go for the “stack them high” approach which is pervading education and healthcare, which is perfect for private equity investors. However, this system is clearly not ideal for all, and this is clear not a market led by the end-“consumer”. Characteristics of markets where there is poor competition due to lack of participants include an inability of customers to lower prices and an ability for suppliers to increase prices, while providing the essentially the same product. This is what has happened in a whole string of privatised industries, including gas, electricity, water and railways, and the (relatively) “simple” hernia operation is going to be no different. Whose going to benefit from offering a contracted core NHS service? Of course, the corporates whom I don’t dare to name because of their legal teams. Will the patient benefit compared to a NHS ideal of “comprehensive” and “free-at-the-point-of-use”? Absolutely not.

Monitor and the regulation of pricing in the NHS

Monitor is in its infancy, but, pardon the pun, I would like to describe an example of childbirth to explain the mountain of problems that the new privatised NHS is yet to experience. Consider this a steep learning-curve that not many of us voted for at the last election.

“The new NHS provider licence: consultation document” was issued by Monitor on 31 July 2012 with a deadline for responses determined as 23 October 2012. According to section 5.1 of this Document on pricing,

“One of Monitor’s new functions will be to set prices for health care services funded by the NHS.Accurate pricing is essential to ensure that providers are paid appropriately for services they provide to patients. Accurate pricing information helps GPs, commissioners and providers to plan and budget for health care services to meet people’s needs. Pricing can also be used to encourage providers to improve the quality of services for patients, and to increase the efficiency with which services are provided. If providers are not properly reimbursed, this can reduce the quality and efficiency of care they offer and may, in some circumstances, threaten the sustainability of their services.”

Pricing is pivotal in markets, and will obviously therefore be expected to the subject of considerable scrutiny by competition regulatory authorities. In future, Monitor will be responsible, in partnership with the NHS Commissioning Board, for setting prices for NHS services. Indeed, according to a statement produced on 20 June 2012,

“The Health and Social Care Act 2012 makes changes to the way health care is regulated in order to strengthen the way patients’ interests are promoted and protected. Monitor’s role will change significantly as we take on a number of new responsibilities. We will become the sector regulator for health care, which means that we will regulate all providers of NHS-funded services in England, except those that are exempt under secondary legislation.”

Take for example the cost to the taxpayer of a provider delivering a baby – not the antenatal or postnatal packages, but the cost of the actual labour and peri-partum process (“the package”). Like any other “product” in the market, a supplier will have to price its product carefully, to ensure that it offers a competitive price, but especially to ensure it does not price itself out of the market by being too costly. The price of “the package” might be determined through a number of different ways.

- Premium pricing (also called prestige pricing) is the strategy of consistently pricing at, or near, the high end of the possible price range to help attract status-conscious consumers. People might buy a premium priced product because they believe the high price is an indication of good quality.

- Cost-plus pricing is the simplest pricing method. The firm calculates the cost of producing the product and adds on a percentage (profit) to that price to give the selling price. This method although simple has two flaws; it takes no account of demand and there is no way of determining if potential customers will purchase the product at the calculated price. You only need to consider the complexity of doing the calculation for the package”, e.g. will the provider use cheap epipdural needs for the anaesthesia, will a foundation year doctor (who is cheaper) perform most of the medicine compared to a specialist registrar (who is more expensive, but more experienced, especially in dealing with medical emergencies).

- Value-based pricing – a price based on the value the product has for the customer and not on its costs of production or any other factor. The relevant issue is how much would you be prepared to have provider A deliver your baby? This is a subjective issue, not easy to predict.

The problem with premium pricing is that providers can collude lawfully to set their prices as high as possible between them. Price fixing is illegal under Article 101 TFEU of the European Union:

Article 101

(ex Article 81 TEC)

1. The following shall be prohibited as incompatible with the internal market: all agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices which may affect trade between Member States and which have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the internal market, and in particular those which:

(a) directly or indirectly fix purchase or selling prices or any other trading conditions;

(b) limit or control production, markets, technical development, or investment;

(c) share markets or sources of supply;

(d) apply dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions with other trading parties, thereby placing them at a competitive disadvantage;

(e) make the conclusion of contracts subject to acceptance by the other parties of supplementary obligations which, by their nature or according to commercial usage, have no connection with the subject of such contracts.

2. Any agreements or decisions prohibited pursuant to this Article shall be automatically void.

3. The provisions of paragraph 1 may, however, be declared inapplicable in the case of:

– any agreement or category of agreements between undertakings,

– any decision or category of decisions by associations of undertakings,

– any concerted practice or category of concerted practices,

which contributes to improving the production or distribution of goods or to promoting technical or economic progress, while allowing consumers a fair share of the resulting benefit, and which does not:

(a) impose on the undertakings concerned restrictions which are not indispensable to the attainment of these objectives;

(b) afford such undertakings the possibility of eliminating competition in respect of a substantial part of the products in question.

It has been incredibly hard to prove price-fixing, but numerous examples exist.

For example, the Daily Mail recently reported price-fixing at the petrol pumps:

“Motorists are being ripped off by profiteering oil companies and speculators, MPs suggested yesterday.They demanded an inquiry into allegations of price-fixing at the pumps, and called for the Government to replace its planned fuel duty rise with a windfall tax on oil company profits.

And last year they reported on the price-fixing of milk:

“Supermarkets and dairy firms have been fined almost £50million over price rigging on milk and cheese that cost families £270million. The collusion put up the price of milk by 2p a litre – 1.2p a pint – and added 10p to the cost of a 500g block of cheese. The punishment was announced by the Office of Fair Trading, following an investigation triggered by whistle blowers at the Arla dairy company. First revealed by the OFT in 2007, the ‘Great Milk Robbery’ took place in 2002 and 2003. But only now has a fine of £49.51million been handed down.”

For Monitor, regulating this will be a mammoth task. Private health providers have much scope for setting between them the most profitable way of delivering the patient’s baby, and it is a great market to be in: the country will never be short of a need for providers of safe deliveries of babies. Whilst other metrics might be important to the clinician, such as mortality or morbidity (infection rates), it could be that private providers are distinguished most themselves by the least cost to a GP practice. Or, it could be that people are genuinely fickle about not caring about who picks up the tab, but the preferred private provider might provide “extra frills”, like en-suite TV with 80 channels.

The problematic issue is what happens if an unconventional problem comes out-of-the-blue. The mother might experience a rare type of headache, such as trigeminal autonomic neuralgia (“TAN”), and there is effectively no “patient choice” involved, save for the GP having to refer the patient to a specialist unit like Great Ormond Street Hospital (“GOSH”). You will notice here that the quality of patient choice is nothing to do with the innovation of the private health provider (can a private provider suddenly make the five stages of labour turn into a more profitable six?), nor indeed how “competitive” the market of private providers of childbirth is (can we get down the speed of the first one from an average of 48 mins to 44 mins?). It is, however, entirely to do with the skill of the clinician in making a rare diagnosis, and having the astuteness of having a specialist unit such as Great Ormond Street Hospital deal with it safely, whatever the cost. You must note that I give this example of TAN at GOSH completely at random, and any similarity to a real-life scenario is of course completely unintentional.

The business model of the company, albeit in the NHS, is not in the national interest

In the new-look National Health Service, certain providers, whether they be private-limited companies or public-limited companies, will be guaranteed work from being able to charge the NHS however they wish to produce their services. They can choose to opt out of all sectors which they consider to be unprofitable, and ‘cherry pick’ what type of work it does. They are mandated by law to maximise shareholder divined.

The UK needs the structure of a National Health Service, with a clear direction about the prioritisation of clinical services at a national level. Otherwise, unprofitable health services will go insolvent and disappear from the NHS, unless the NHS is rigorously regulated.

With the progression of the new Health and Social Care Act, the horrific effect will be, unfortunately, to penalise areas of the UK where health inequalities are known to exist (for example coal miners developing emphysema or chronic obstructive airways disease through their work, or British-Bangladeshis having a high prevalence of heart attacks or strokes in Tower Hamlets through a genetic predisposition to cardiopathic traits such as hypercholesterolaemia).

We have seen precisely this problem with markets before. “Oligopolistic” markets are where there are few competitors. If an oligopolistic market then exists, the customer (or patient as he or she should be known in the NHS) may come last, as the need for shareholder primacy takes over. In gas or water, markets also privatised by the Conservatives, there is actual little competition for the consumer, prices are high, the quality of the service has not vastly improved, and shareholders have made a massive profit. Unfortunately, health is the perfect market where this deception can take place, as metrics appear in health reports, which emphasise waiting times or bed days, as the number of patients with ‘hidden’ problems, often unprofitable to treat, such as dementia or depression go unnoticed.

The real workers in the NHS are doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals, many of whom have difficulty in defining an ‘excellent outcome’ in the NHS even after a lifetime of dedicated hard work often with unbelievable stress and experience. These healthcare workers and employees need the protection of the Unions, particularly over employment rights, and need to feel valued in the NHS. It’s completely wrong if they should become merely ‘disposables’ for venture capital companies to generate a profit; the fact that reports of running roughshod over UNISON exist, and the fact that the Medical Royal Colleges have been steadfastedly opposed to the reforms, means that this is a very dangerous path for the NHS to go down.

Shibley is a member of Labour, and a member of the Socialist Health Association. He has postgraduate degrees in medicine, natural sciences, law and business.

Why is Apple so successful?

I have just completed my marketing course for my MBA. In this course, we have looked at the branding and market positioning of products, and how they are ultimately priced. Apple’s marketing strategy (and distribution channels) continues to interest me. I wonder how it chooses to develop new products, and retains its competitive advantage.