Home » Posts tagged 'leadership'

Tag Archives: leadership

You hate Corbyn if you want to but do you really want to live in a right-wing dictatorship?

Hate is such a strong word.

But passions do indeed ‘run high’ at election time, even if this is the third plebiscite in two years. Indeed, today is the anniversary of the 2015 general election.

The EU referendum was a landmark event in British politics for all the reasons which have been well rehearsed elsewhere. But why it is particularly noteworthy is that it somehow managed to galvanise members of the Conservative party into a strongly anti-EU party under the rationale of ‘will of the people’.

It is this ‘will of the people’ argument which has totally ignored the will of 48% (and even some of the 52%) who have never had an official way to articulate what it wanted to be on exiting the European Union. A perfectly possible position for the Labour Party to take would have been to be side opposite to UKIP but still respected the ‘verdict’ of the referendum.

We all have differing views of ‘leadership’. Angela Eagle MP had her chance to articulate her views of ‘real leadership’ last year at a time when the Labour Party was faced with a bland option of Owen Smith and Angela Eagle, or rather than supporting Jeremy Corbyn.

I heard a new Labour person sneer on the radio the other day, “I’d be surprised if Jeremy Corbyn had a smartphone.”

Let’s get this straight – this is not debate, this is BLATANT AGEISM.

Jeremy Corbyn clearly hasn’t done everything right – but he has been dealt a very bad hand. His 172 MPs are revolting in every sense and, with a few exceptions, have been sitting on their hands and sticking fingers in their ears, when they haven’t been openly slagging off Corbyn as is the wont of Alas Kinnock and Woodcock.

There was never a coherent debate within the parliamentary Labour Party of how the potential policy arms could be reconciled with Middle England.

Let’s be blunt. The behaviour of the ‘liberal press’ has been far from liberal. It’s given a disproportionate time to certain voices and the expense of annihilating the character and reputation of Jeremy Corbyn.

I would list at this point all the Guardian journalists who have been snide, antagonistic, pathetic, vituperative, negative, snide, smarmy, malicious, nasty, uncooperative, arrogant, unpleasant, but I can’t be bothered with them as human beings.

The Guardian has successfully, with others, turned England into a far right dictatorship, where it is acceptable to put up with robotic words such as ‘coalition of chaos’ and ‘strong and stable’ in the absence of a lack of debate about lack of meeting NHS targets including A&E times, the burdgeoning PFI bills, the closure of mental and physical health beds, the lack of access to your local GP, the anger amongst junior doctors over their new contract, the pain of junior nurses with training and cost of living pressures.

The Guardian are the Daily Mail of the left, except with the odd veneer of pseudointellectualism which is now fooling no-one. They spew bile and hatred towards any well meaning debate from left, and it’s pure hatred – in the name of Corbyn being an ineffective leader.

And for a couple of years this has been mainstreamed, and nobody bats an eyelid. The plan B to make UKIP a big force in politics has failed (apart from the fact that racist, elderly bigots have now been safely rehoused in the Conservative party).

The plan C to make the Liberal Democrats the third party has been doomed due to unnecessarily hostile tribalism from its leadership, and problems on its position over gay sex. Also, nobody at all can take their position on an extra penny on income tax for health and social care seriously after their Herculean somersault on tuition fees.

I salute the journalists in Guardian for not only carrying out the most complete character assassination of the left in my living times, but also for trying to extinguish the hopes and dreams of people like me who felt completely stuck in the rut of the same failed policies by the same hierarchy.

And all this for a woman who will not debate her policies, can only go to empty warehouses in England by helicopter, and who thinks that regurgitating the same memes wherever she goes is worthy of her second class degree from Oxford.

That woman can be intensely proud of her pathetic attack on the leadership of the European Union, but I for one thinks that she will get a firm two fingers salute from their leadership when she comes to negotiate the UK position. And 28 are more powerful than 1.

None of Corbyn’s critics can mount a coherent criticism against any of his domestic policies.

Call it what it is, please – this is simply a personal hate campaign with very sinister aspects of ageism.

I have no time for the new emboldened Tory, Unionist and UKIP Party. The Guardian can go to hell too.

Many Labour MPs are on suspended sentence – and they know it

It’s impossible to escape the conclusion that the failed coup (and it wasn’t even that in the end) did quite a lot of damage to the perception of Labour. At a time when the UK was reaching an existential crisis, as to whether it should be a Union or part of it, Hilary Benn made himself into a political Archduke Ferdinand and precipitated world war within Labour. Benn Junior’s legacy was a real “* you” to the membership, given that it is ubiquitously accepted that the general public will always punish divided parties as a rule of Newtonian classical dynamics.

The post-truth era for Jeremy Corbyn had of course begun long before his second election as Labour’s elected leader. It’s no mean feat for Rafael Behr or James O’Brien to continue their boring whingeing about Corbyn all the time, but to give them credit they need to pay their mortgages. But other people need a Labour government. The meme ‘Britain needs a strong opposition’ laying the blame at Corbyn of course is completely laughable given the torrent of abuse at Corbyn from all of the mainstream media, whether it’s on the inclination of his bowing in official ceremonies, the lack of singing at the National Anthem, or the alleged refusal to kneel and kiss at the Privy Council inauguration ceremonies.

Corbyn does not have the Twitter following with the magnitude of Donald Trump. He would not wish to boast about ‘expanding his arsenal’ either (pardon the unintentional pun about the Holloway Road in Islington). Nor is he best friends with Vladimir Putin. Talking of which, all of the pseudo-commentators who were spitting bullets at Corbyn’s morality seem to have gone deadly quiet about Trump’s ‘locker room’ banter, did you notice?

For all the talk about strong leadership, Jeremy Corbyn is no Adolf Hitler, Donald Trump or Nigel Farage. It’s hard to disagree with his ten pledges, which include the ‘bread and butter’ for many of us on the left wing of politics. Take for example the pledge ‘full employment and an economy that works for all’. George Osborne’s legacy, possibly not meriting a CBE, was to produce one giant ‘gig economy’, with workers having desperately and deliberately poor employment rights, many on zero hour contracts, and many being topped up with ‘working tax credits’ (hence becoming the ‘working poor’). Unsurprisingly, this has done very little to tackle the poor productivity of the UK in general, and the poor tax receipts have been a shocker for running public services safely.

A second pledge is impossible to disagree with. That is, “Secure our NHS and social care”. The emphasis of the current Conservative government has been a traditional one of ‘getting more bang for your buck’ and the euphemistically termed “delivery”, but the crisis in social care has been due to a toxic combination of imposition of private markets and lack of funding matched to demand since 2010. Even Conservative MPs are concerned about the parlour state of social care, which is also having a cost in the economy in people of working adult working age being unable to lead independent lives because of the need to care for “dependents”, for example people living with dementia with substantial caring needs. For a very long time, A&E departments nationally have been unable to meet their targets, and delayed discharges have gone through the roof. But this is not headline stuff due to a corrupt mainstream media – hellbent on their character assassination of Jeremy Corbyn.

No poll, even up until the night of Donald Trump’s eventual election, had predicted accurately the scale of the Republican victory. The general public are continuously being told about the unelectability of Jeremy Corbyn, however, even though British pollsters have a formidably catastrophic recent polling record, for example in the EU referendum or the 2015 general election. No amount of fiasco is too large to displace the vitriolic attacks on Corbyn, whether that be the failure of privatised rail services, the corruption of captains of industry for well known high street brands, an ability to curb the excesses of unconscionably paid people, and so on. But Corbyn himself would be the last person to bank on a three full terms with him as Prime Minister. He is currently 67 – not being ageist, but he would be over 80 if he completed three full terms for Labour. The succession planning for Tony Blair was an unmitigated disaster, reputedly because many of the successors did not want to ‘succeed’ taking up profitable jobs elsewhere.

Talking of which, Jamie Reed is doing himself and Labour simultaneously a favour. There is more of a chance of a pig landing on Mars, than there is a chance of Reed winning in the strongly Brexit seat of Copeland. It is a fact that Labour cannot triangulate itself into making itself very pro European Union for the benefit of many in Scotland and London, while also being anti European Union for very many in England. Whilst there are a few with extreme opinions such as ‘send Muslims back’, there are some who hold the opinion that EU workers are ‘stealing the jobs’ of indigenous citizens due to being able to work at lower salary rates. Theresa May MP has been consistently unable to stick to immigration targets, and Hilary Benn MP would have been better off campaigning on this than sticking the political knife into Jeremy Corbyn? It’s pretty unlikely that Theresa May will be able to deliver on both exiting completely out of the single market and exempting itself from free movement of people, meaning that there’ll be a lot of disappointed people around.

The LibDems have already made their bed, which they intend to lie in. The possibility of another Tory-LibDem coalition beckons (particularly if Kezia Dugdale keeps up her triumphant work of Armageddon in the Scottish labour vote; this catastrophe long predates the Corbyn factor). They in case are not the party of the 52% or the 100%, but the 48%.

I suspect people who claim to want a ‘strong opposition’ want nothing of the sort. They are prepared to continue to undermine Jeremy Corbyn at all costs in 2017, and are fully prepared to see Theresa May secure a mandate for a hardline exit from the European Union.

Jeremy Corbyn for the time being has taken back control of the Labour Party, but his strategy has paradoxically been to make himself not dependent on others to the point of being isolationist. But the strength for Labour will be, as always, when the whole works for the collective good, and is larger than the sum of individual parts. If some people with big egos don’t feel they wish to suffer the indignity of losing under Corbyn for their own beliefs, and want to leave, that can only be interpreted as a good thing. If they can offer constructive criticism as leading Commons select committees, that I suppose is good potentially too. Strictly isn’t bad either.

But if they’re just going to whinge holding onto minor London seats, or larger, they’re better off getting out for the sake of all of us.

Why the level of vitriol against Jeremy Corbyn?

Whilst literally a derivative of metals, ‘vitriol’ according to the Oxford Dictionary, means bitter criticism or malice.

I quite enjoyed the pantomime of yesterday’s Prime Minister’s Questions, the last appearance in that context from David Cameron. The body language on the front row was somewhat tense between Theresa May MP, about to be invited by the Queen to form a new government later that afternoon, and George Osborne MP, about to be sacked by the new Prime Minister.

Osborne, the Chancellor or ‘Chancer’ as he affectionately came to be known, had an atrocious record in government. This included at various points downgrading of the national credit rating, missing of all his self-set targets, and a ballooning national debt which in a few years of his tenure had even superseded the total which Labour had amassed in thirteen years.

Craig Oliver, close to the Cameron government, called Cameron the ‘quiet revolutionary’. It was a genuine belief, it appears, of that incoming Government in 2010, that they were coming together in the national interest to deal with a large financial deficit left by Labour. Much of the Ed Miliband time in government was spent in critics of Labour drawing attention to this deficit, without Ed Balls doing much to address how it came about, arguably leading to his personal defeat and the Labour Party’s defeat in 2010.

And yet the economic performance of Osborne was bad. He was personally blamed in the sense that he was boo-ed at the Olympics. David Cameron, as it happens, was boo-ed twice this week, first with his mother at the Wimbledon final on Sunday, and second yesterday with Sam and children as they left Downing Street.

However, approval ratings of Cameron ‘as a leader’ have been consistently high. Even there was no putsch to get rid of Osborne, despite his atrocious performance. Cameron could always point to other aspects of the macroeconomy, but mainly a record level of employment. The qualification to this routinely trotted out by Labour was that this was mainly due to zero-hour contracts, but the Conservatives were able to combat this criticism with various statistics. Not once was it ever conceded that a record level of employment might have been due to a free movement of persons, something which you could credit the EU for.

Nobody openly asked for Osborne to be sacked. There was no coup against Osborne. Osborne and Cameron, despite the reality of the situation, were keen not to portray any psychodrama as had dogged the days of Brown with accusations of throwing Nokia phones. Such a schism would have done much to destabilise a Government, now with a wafer-thin majority. Any destabilisation might have set in process events which could cause a motion of no-confidence in the Prime Minister leaving due to the Fixed Term Parliaments Act (although this statutory instrument was first devised to stop the LibDems from leaving the coalition.)

The contemporary meaning of vitriol these days is ‘bitter criticism’ or ‘malice’. Through the way that the defamation law works in England, you can’t sue me if I say something that’s true, or fair comment; or said perhaps in a court of law or parliament (even if the accusation is a strong one like being a ringleader of a pornography ring). But defamation is defeated by malice.

For supporters of Jeremy Corbyn, which includes non-exclusively ‘Corbynistas’, it has always been difficult to tell how much of the criticism is motivated by malice. People who haven’t experienced first hand the working style of Jeremy Corbyn will find it difficult to opine on his team building ability. However, when you get criticisms like ‘the leader’s office won’t even pick up the phone’, one is forced to wonder how much experience such critics have of the real world. I, for example, normally find it impossible to get hold of anyone in a large organisation. I don’t think I’d even know where to start in finding someone at the BBC or the NHS , let alone parliament.

Therefore, it has become easy to approach criticism of Jeremy Corbyn, even if valid roots, with much cynicism. For example, when you have Lucy Powell on the airwaves talking about how Corbyn doesn’t leave the bunker, or Angela Eagle saying he is shut behind ‘closed doors’, this produces massive cognitive dissonance with the numerous images of Corbyn addressing confidently large rallies in public.

Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership hustings appearances are available for all to see on You Tube. In fact, I recommend you watching them with the benefit of hindsight of who actually won. It’s obvious how the presenters undermine his existence at these debates by “begging up” the three other candidates (Kendall, Burnham and Cooper), of good New Labour stock compared to him, in both unspoken ways and spoken ways (“Jeremy Corbyn sneaked onto the ballot and had the fewest nominations by far“).

Corbyn has never been popular in the parliamentary party. In his heyday, he amassed 36 nominations, and this included Dame Margaret Beckett who was later to yield a verbal machete to him saying she had been a ‘moron’ a term widely used by John McTernan. McTernan mysteriously had become the self-selected expert of campaigns despite his heavy recent defeats in Scotland and in Australia. McTernan’s mission was to make Jim Murphy the Scottish heir to Blair, but of course that went belly up. The number of people who did not vote ‘no confidence’ (who logically do not necessarily hold confidence) was 40 the other week.

The late not so great Margaret Thatcher used to have a phrase ‘oh he’s one of us’. Corbyn is clearly not one of them, not having graduated through Fabian Women (joke), or Progress. He did not go to Oxford or Cambridge.

Corbyn has voted for what he has perceived as ‘good law’, and in fact these tend to be the same examples Blairites use to describe their successes. such as the Equality Act or the national minimum wage. He has, however, voted on principle against the whip on matters he disagrees with, including the Iraq War. Tony Blair somehow managed to give an hour’s speech the other day in response to Chilcot without proferring an apology for the hundreds of thousands of innocent deaths, or the argued lack of due process in going to war including rigid observance of international law.

Corbyn was attacked for his perceived lack lustre performance in the EU referendum campaigning, even though he says he toured flat out to argue for the benefits of staying in a reformed Europe. This was exactly the same pitch as the Prime Minister’s, knowing that most of the country were fundamentally 50/50 or by a smidgeon ‘reluctant Brexiteers’. Cameron achieved 10% less than Corbyn “remainers” in their parties. Margaret Hodge MP representing a constituency profoundly Brexit blamed Corbyn and launched the no-confidence motion in him. But everyone knows that there were unresolved local issues in Barking and Dagenham, due to community disquiet about immigration.

All of this narrative is to frame Corbyn as a ‘failure’, and personally responsible for 52/48 vote in the EU Ref. But there were many other actors in the EU Ref, such as Alan Johnson MP whose own campaigning really was dismal. And the ‘failure’ narrative is catalysed by the idea that somehow voters are gullible or stupid, and it’s Corbyn’s fault not to have put his heart into setting out the case. Or even worse, many of his own voters are actually closet racists, and wanted to leave the EU, but Corbyn’s relative silence had somehow tipped them over the edge. It could be possible, for example, for all the best will in the world that many Labour voters consider themselves internationalist rather than attached to the EU – for example, Liz Kendall and Yvette Cooper specifically referred to themselves as ‘internationalist’ as regards the UK’s place in the world in the Labour Leadership hustings last year.

This is not only profoundly insulting to Corbyn but also to the voters in the UK who voted for Brexit. Worryingly, it seems to be phenotypic of an arrogance, or at least out-of-touchness, of a part of Labour political class which does not really understand the immigration issue. Labour MPs are either intensely stupid or highly fraudulent to ‘blame’ Corbyn for that. Hilary Benn also might like to ‘react’ to the fact that the Conservative Party have just appointed two SoS Dr Liam Fox and David Davis MP as International Trade and Brexit ministers respectively – are the Tory Party getting chummy with UKIP voters because they think this holds the key to winning?

The reality is, nonetheless, that there have been moves afoot to undermine Corbyn and to get rid of him from day one. This is not paranoia. This is evidenced fact. Yesterday, John Mann had stated openly that he had been approached by a member of Owen Smith MP’s team about a possible leadership challenge six months ago. There has apparently been a Gmail list so people can co-ordinate action against Corbyn. All the media papers have taken a strong line against Corbyn, even though he has met all his local election challenges and has had a number of high publicity policy successes (e.g. on working tax credits).

We know that the Corbyn team has been undermined from day 1, and even before the actual announcement of the result of the election. As Tony McNulty MP correctly pointed out the other day there is a difference between ‘lack of solidarity’ and ‘people who simply disagree with you’. But it has to be remembered that potential key players has refused to work with Corbyn even pre-dating the result including Cooper, Reeves and Umunna. This of course has been incredibly frustrating for the Corbyn team.

The premise for the rejection of Jeremy Corbyn’s positioning is that his policies are radical, dangerous or plain weird. The outstanding problem is they are hugely popular with vast swathes of the current blossoming membership of Labour – for example improving the quantity and quality of social housing, doing something about the unconscionable poor value for money PFI contracts in the NHS, tackling at long last the failure of numerous success governments in tackling aggressive tax avoidance, not using austerity as an excuse to impose policy damaging the most vulnerable in society (such as welfare benefits for citizens who are physically disabled).

There is little real appetite to airbrush genuine serious inclusion problems in Labour which pre-date Corbyn. Unfortunately, some of the accusations of anti-semitism have been confused with genuine criticisms of the Netanyu government. It has been deeply unpleasant for people like me on Twitter, who are not anti-semitic at all, to be accused of being immoral for appearing to support Jeremy Corbyn.

Another “guilt by association” is the conflation of being a supporter of Corbyn with being a member of Momentum – and the meme that all members of Momentum are violent and aggressive Trots. Such high standards of guilt by association are not held, for example, for Thatcher and Pinochet, or certain people in Saudi Arabia Tony Blair has been photographed with with less than great records on human rights.

The ‘not one of us’ legitimises a reluctance to integrate with Jeremy Corbyn, meaning that there is little outward motivation it seems for the Labour parliamentary party to work with their leader. This is of course incredibly demoralising for people who have legitimately voted for Corbyn. Not all ‘entyists’ are people who know nothing about politics – many are indeed ‘returnists’ who have finally found a political philosophy they can agree with, from which they had felt disenfranchised.

For all the talk of Hilary Benn of winning, who has a vested interest in protecting the reputation of the policy of New Labour, there were serious flaws in policy in the New Labour era. One clear example is a target-driven culture, together with a rush to regulation and imposed financial constraints, which led to problems such as Mid Staffs, arguably. But there were others, such as disabled citizens feeling Rachel Reeves MP had very little interest in standing up for their interests. The decline of social care had become legitimised under New Labour, which is a massive problem as the NHS and social care operate in one ecosystem. This is all objectively captured in Labour progressively losing shares of the vote, even while ‘winning’. And the implosion in Scotland is undeniable.

The ‘not one of us’ narrative is incredibly pervasive. One of the attacks of Cameron, one of his more popular ones, was the report of his mum saying Corbyn’s choice of suit in #pmqs was unprofessional.

Corbyn yesterday was wearing a much more expensive suit, and Cameron was happy. It is uncertain what other personal sacrifices Corbyn has had to make to placate the mass media, like brushing the Queen’s hand when he became a Privy Councillor, nodding at a respectable inclination to the Queen, singing with gusto the National Anthem, and so on. These are not reasons to hate Corbyn – merely bully-boy excuses.

Margaret Hodge has repeatedly referred to the culture of ‘intimidation and bullying’ under Corbyn, and yet it is precisely a culture of intimidation and bullying demonstrated by Labour MPs touring TV studios trying to humiliate publicly Corbyn. They could spend more time doing their actual work.

All of this is a far cry from the murder of Jo Cox only recently. But for Hilary Benn ringing round collecting signatures of people who couldn’t work with Corbyn to relay to Corbyn in his face, Benn probably would not have been sacked. And the ludicrous situation would not have occurred where the NEC by only four votes allowed Corbyn to go automatically onto the ballot paper. It is pretty certain Corbyn will now win, with 171 parliamentary MPs having declared ‘no confidence’ in him. It is even more likely that he will win if the Eagle and Smith votes split the opposition. Owen Smith MP is not naturally attractive to core Labour voters because of his stance on NHS privatisation. Much core support for Labour has been lost of late in their lack of perceived defence of public services.

“The member of Parliament for Pontypridd, Owen Smith, has been outed as a supporter of greater private involvement in the NHS, only hours before his wife Liz Smith asks for the support of the people of Llantrisant in voting for her.”

“Prior to standing for election Owen Smith worked as a lobbyist for drugs firm Pfizer. During that time, Owen Smith called for more involvement of such private firms in the NHS. “We believe that choice is a good thing and that patients and healthcare professionals should be at the heart of developing the agenda,” he said on behalf of the firm.”

“Asked to explain why he sought public office whilst earning a six-figure sum from Pfizer, Owen Smith said Pfizer were “extremely supportive” of him seeking to enter Parliament. Speaking about the early-day motion to reduce the involvement of Pfizer in the NHS, Owen Smith added: “We (he and Pfizer) feel that their (other wholesalers’) campaign to mobilise opposition to our proposals is entirely motivated by commercial self-interest.“”

On PFI, Smith declares, “I’m not someone, frankly, who gets terribly wound up about some of the ideological nuances.” These ‘ideological nuances’ have instead caused much taxpayers’ money to leach out into the private sector at an unconscionable rate, stripping the NHS bare of money for frontline staff.

If it quacks like a duck, it probably is a duck.

So – if the party is intensely relaxed about City-friendly policies, and the culture of the parliamentary party is fundamentally different to the membership, the logical conclusion is that the leaders for the overall party and the parliamentary party are not necessarily the same. But in a case of ‘who gets to keep the china’ in divorce proceedings, there is a legitimate question of whether Unions should sponsor MPs who are perceived to undermine the leadership.

“Representatives from the CWU Bristol branch, which has 3,000 members, voted unanimously to halt payments to all three MPs last Wednesday and the decision was ratified this week. Their plans were announced at a pro-Corbyn rally on June 29.

Wotherspoon said: “If someone wishes to stand against the leader there is a process for that – and there will be an election, which is entirely fair. We would expect Jeremy to be returned with an increased mandate.

“These MPs did not bother to meet with their local parties or supporting trade unions before getting involved in this failed coup, who would have overwhelmingly opposed such action.””

Be in no doubt – Corbyn is the victim of real toxic leadership from other Labour MPs and ‘media friends’ of theirs.

Whereas his critics are making much noise, Corbyn looks set to a peaceful ‘quiet revolutionary’.

But he will need to neutralise at least the vitriol of others aimed at others, like the very dangerous levels of nastiness at female MPs – from a class of misogynist terrorists. The very least is that he should expel them after due process from the Labour Party if at all connected. The stand on this has not been strong at all, giving the impression that Corbyn does not actually care (which is presumably not the case). Also, there has been very little in the way of detail for Corbyn’s policies as opposed to grandstanding on pretty unobjectionable socialist (but moderate) policies. Much of the fear that these policies are extremist I feel could be mitigated against if Corbyn had a crack team of intelligent policy people who could work out how to operationalise his strategy, for example on negotiating PFI or tackling aggressive tax avoidance. This does mean a universe more substantial than the leaders’ office, and possibly substantially more resourcing unless there has been a boom in Paul Mason post capitalism. Corbyn and McDonnell have made huge inroads in economic policy, despite some casualties, but health and social care would be a one to target next. Furthermore, it will be necessary to draw on existent work, including the anticipated work on #Brexit from May’s government and the civil service. If #Brexit is going to be the big issue in the next four years, there might NOT be much time, money or inclination to turn the UK into a socialist superstate nirvana anyway.

The situation is rather tragic actually, but, as someone who has voted Labour for the last 26 years for all of my adult life, I can say confidently it is all of the parliamentary Labour Party’s making. Just look to see the humiliation Corbyn had to go through with the NEC, when the rules were perfectly clear that he would be entitled automatically to be on the ballot.

Jeremy Corbyn might even win in 2020, so get over it.

And so, as Mahatma Gandhi said once, “First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.”

I remember watching the BBC Newsnight Labour leadership hustings when they first happened, quite some time ago. I recall Jeremy Corbyn MP being introduced derisively as the old candidate who’d only just managed to make it onto the ballot sheet. And yet as I listened to Jeremy’s responses it became clear to me that his answers were addressing that significant electorate; those people who felt totally disenfranchised by Labour in the last ten years.

The odd thing about ‘choice’, so exuberantly espoused by both the Conservatives and Labour Party, in recent years is that you come in for rather heavy abuse, some of it of a rather personal nature, if your choice disagrees with someone else. I really can’t rationalise how Tony Blair came to think it was acceptable to state that if your heart is with Jeremy Corbyn you need a heart transplant. But as the campaign has progressed, things have been increasingly desperate. Every man and his dog from New Labour, including Alastair Campbell and David Blunkett, have been wheeled out to deride Corbyn. I am particularly puzzled how David Blunkett came to think he could produce the deal maker for the Blair era, when he has been happy being paid as an advisor on corporate social responsibility for the Murdoch operations.

That the main Union leaders wish to support Corbyn does not surprise me. That Keynesian heavyweight Lord Skidelsky has produced a coherent argument to explain why ‘Corbynomics‘ is not as extreme as some present does not surprise me either. That serious heavyweights in economics wish to lend their support to Corbynomics is not a shock, in addition. This was to be expected with the huge social movement which accompanied the work of Prof Kate Pickett and Prof Richard Wilkinson, for example “The Spirit Level”.

What I was seriously caught out by is how wise leading commentators, particularly at the Guardian, were so keen to sneer at Corbyn. I can understand the thing about not wanting to jump on the bandwagon, but their position was totally untenable. There was little attempt to engage with the actual policies, or to query why so many members of the general public had engaged in what was patently more than a mass hysteria ‘Corbynmania’. This does disappoint me, as some of the commentariat included bright people, sympathetic to the aims of New Labour and the Blair governments, who really could not meet half way with Corbyn.

If it happens that Jeremy Corbyn wins, and let’s face it the polls have been wrong before, I am hoping that members of Labour will pull ranks to help Corbyn. I as it happens have voted in this election, as I was entitled to as a Labour member. Not being offensive, but it might have helped that I haven’t left tweets and Facebook posts banging on about how wonderful the Greens are.

Rupert Murdoch commented in a tweet that Murdoch seems to be the only one who seems to be very clear about what he stands for. Corbyn has had plenty of time to rehearse the arguments in the front of the bathroom mirror, but I dare say he has thought exactly why he felt unable to support tuition fees, Iraq, or the private finance initiative, even having been elected on the same ‘disastrous’ Michael Foot manifesto which first saw him elected together with Tony Blair.

The arguments are very well worn. If there is money for war, why is there no money for social care? The criticism should not be why Corbyn is able to go over the same territory as the 1980s politically, but why these arguments have particular traction now. It is simply the case that the opposition from Labour has been unacceptably weak on the destruction of social care, which is a calamity in itself, but also disastrous from the perspective of how the National Health Service functions.

Repeated apologies for misdemeanours and misfeasance from the past have their place, but only if correct and authentic. The candidates for the Labour leadership have clearly been unable to settle with united voice on the actual reason Labour should be criticised; despite ambitious spending on public services (such as Sure Start or the infrastructure of hospitals), it was unable to regulate the City of London stringently enough. It happens that the Conservatives agreed with this light-touch regulation, and levels of public spending too, but that is not really the point as they were neither in office nor in government at the time.

Labour has never ‘apologised’ for the Iraq War, despite the sequelae, presumably on the basis that it feels it has nothing to apologise for. But there were screw ups in decisions from Labour. Many in the general public find it inconceivable that the Labour leadership, apart from Jeremy Corbyn, aren’t making more of a noise about the destruction of the Independent Living Fund; and abstaining on the welfare reform bill is testament to how some feel there is no alternative to austerity.

Currently a large proportion of NHS Foundation Trusts are in deficit. Many feel that some Trusts, in chasing targets and wanting to become Foundation Trusts, became extremely dangerous from a patient safety perspective, and this legacy from New Labour must not go unchallenged either. Whether or not Jeremy Corbyn can actually win in 2020 is in a way irrelevant to the huge strides forward in re-establishing socialist principles back on the political map. It could indeed be the case that Sir Keir Starmer QC MP is parachuted in just before the 2020 general election, but the ‘political left’ should not by this stage feel disappointed about their progress here. This progress might not have been what Progress wanted, but giving disenfranchised people a voice is a meritorious goal too.

And he might even win with the clarity of his arguments, even if you disagree with them. So get over it.

Change

Somebody once advised me in my 20s that destiny is when luck meets preparation.

When I was younger, I used to think that you could prepare yourself out of any situation. But wisdom and events proved me wrong. I soon discovered that what you did yesterday though can affect today, and what can affect today can affect tomorrow. The only thing you can predict pretty comfortably, apart from death and taxes, is change. When I was younger, I used to think I could live forever. All this changed when I woke up newly physically disabled, after a six week coma on a life support machine on the Royal Free Hampstead. The National Health Service saved my life. Indeed, the on call Doctor who led the crash team the day of my admission, when I had a cardiac arrest and epileptic seizure was in fact a senior house officer with me at a different NHS trust in London.

This feeling of solidarity has never left me. I do also happen to believe that anything can happen to anybody at any time. I studied change academically in my MBA in the usual context of change management and change leadership. It’s how I came to know of Helen Bevan’s work. I’ve thought a lot about that and the highly influential Sirkin paper. But I don’t think I honestly ‘got‘ change until this year. In 2007, I was forced to change, giving up alcohol for life. I realised that if I were to have another drink ever I would never press the off switch; I would either end up in a police cell or A&E, and die. This is no time for hyperbole. It was this forced change, knowing that I had an intolerance of alcohol as serious as a serious anaphylactic shock on eating peanuts, that heralded my life in recovery. I later came to describe this to both the legal regulator and the medical regulator as the powerful driver of my abstinence and recovery, rather than a ‘fear based recovery‘ from either professional regulator.

But I feel in retrospect my interpretation of this change, as due totally to an externality, is incorrect. As I used to attend my weekly ‘after care’ sessions with other people newly in abstinence from alcohol or other toxins, or from gambling, or sex, I discovered that the only person who can overcome the addiction is THAT person; and yet it is impossible to read about this path of recovery from a book, i.e. you can’t do it on your own. So ‘command and control’ is not the answer after all. Becoming physically disabled, and a forced change of career and professional discipline, and a personal life which had become obsessed by alcohol, meant I had no other choice. I had to ‘unclutch’ myself gear-wise from the gear that I was in, and move into a different gear. But I did find my new life, living with mum, and just getting on with my academic and practitioner legal and business management training intensely rewarding.

In 2014, I attended a day in a hotel close to where I live, in Swiss Cottage. One of the speakers was Prof Terence Stephenson. After his speech, I went up to thank him. I found his talk very moving. He was later to become the Chair of the General Medical Council (GMC). I was later to become regulated once again by the GMC. Two lines of his has kept going through my mind repeatedly since then. The subject of the day was how sick doctors might get salvation despite the necessary professional regulation process. Stephenson claimed: “If you’re not happy about things, I strongly urge you to be part of the change. You being part of the change will be much more effective than hectoring on the sidelines.” This was not meant as any threat. And as I came to think more and more about this I came to think of how much distress my behaviour had caused from my illness, how I wish I had got help sooner, and how looking for someone to something to blame was no longer a useful use of my energies. I am now physically disabled. I get on with pursuing a passion of mine, which is promoting living better with dementia. But if there are any people who are worthy of retribution I later decided then their karma might see them implode with time. Not my problem anyway.

I now try to encourage others where possible if they feel that they have hit rock bottom; I strongly believe that it’s never too late for an addict to break out of the nasty cycle. If you think life is bad, it unbelievably could be much worse. I think businesses like persons get comfortable with their own existence and their own culture, but need to adapt if their environment needs it. I think no-one would wish to encourage actively social care on its knees such that NHS patients cannot be discharged to care, if necessary, in a timely fashion. I don’t think anyone designing the health and care systems would like them to be so far apart deliberately, with such bad communication between patients, persons and professionals. Above all, I feel any change has to be authentic, and driven by people who really desperately want that change. I think change is like producing a work of cuisine; you can follow the recipe religiously in the right order, but you can recognise whether the end result has had any passion put behind it. For me, I don’t need to ‘work hard’ at my recovery, any more. I haven’t hit the ‘pink cloud‘ of nirvana, but I am not complacent either. Change was about getting from A to B such that I didn’t miss A, I was in a better place, and I didn’t notice the journey. If I had super-analysed the change which was required to see my recovery hit the seven year mark this year, I doubt I would have achieved it.

How badly does Ed Miliband want the job?

Ed Miliband has often remarked that he views his pitch for being Prime Minister being like a job interview. This is not a bad way of looking at the situation he finds himself in, one feels.

The “elevator pitch” is a construct where you’re supposed to sell yourself in the space of a short journey in an elevator. What would Ed Miliband have to do to convince you that he means business?

This question is not, “Would you like to be stuck in a lift with Ed Miliband?” But that is undoubtedly how the BBC including Andrew Neil, Andrew Marr or David Dimbleby would like to ask it.

On Facebook yesterday, Ed presented his potted ‘here’s what I stand for in four minutes’ pitch.

It’s here in case you missed it.

Presumably advisers have recommended to Ed in interviews that he must look keen to do the job. But presumably there is a limit to looking ‘too keen': i.e. desperate.

Ed being given the job depends on what the other candidates are like: and Nigel Farage, Nick Clegg and David Cameron are not the world’s most capable candidates.

It’s said that most HR recruiters ‘google’ the candidates before shortlisting. Will Ed Miliband survive the stories about him eating a butty? Or being public enemy no. 1?

Does Ed Miliband have issues he wants to bring to the table?

Yes he does: repeal of the loathed Health and Social Care Act (2012), abolition of the despised bedroom tax, a penalty for tax avoidance, and so on.

Will the media give him a fair hearing?

No.

Does Ed Miliband have a suitable background? Well, he got at least a II.1 – this is all anyone seems to care about these days. (I, for the record, think that the acquisition of a II.1 in itself is meaningless, but that’s purely a personal opinion.)

Would Ed take the job if offered it? Yes.

Will he have OK references? Not if you ask Andrew Marr, but if you ask somebody like James Bloodworth, Sunny Hundal, or Dr Éoin Clarke, yes.

Can Ed return something to his stakeholders? Possibly more than David Cameron can return to his. All Ed has to do is to win.

It’s going to be difficult. This general election on May 7th 2015 is incredibly unpredictable. The main factors, apart from Ed Miliband’s two critics, are whether the LibDem vote will collapse, how well UKIP might do, whether Scotland will be a ‘wipeout’, and so on.

But Ed Miliband’s government repealing the Health and Social Care Act (2012) is far more significant than whether he can eat a butty.

The World Dementia Council will be much stronger from democratic representation from leaders living with dementia

There is no doubt the ‘World Dementia Council’ (WDC) is a very good thing. It contains some very strong people in global dementia policy, and will be a real ‘force for change’, I feel. But recently the Dementia Alliance International (DAI) have voiced concerns about lack of representation of people with dementia on the WDC itself. You can follow progress of this here. I totally support the DAI over their concerns for the reasons given below.

“Change” can be a very politically sensitive issue. I remember going to a meeting recently where Prof. Terence Stephenson, later to become the Chair of the General Medical Council, urged the audience that it was better to change things from within rather than to try to effect change by hectoring from the outside.

Benjamin Franklin is widely quoted as saying that the only certainties are death and taxes. I am looking forward to seeing ‘The Cherry Orchard” which will run at the Young Vic from 10 October 2014. Of course, I did six months of studying it like all good diligent students for my own MBA.

I really sympathise with the talented leaders on the World Dementia Council, but I strongly feel that global policy in dementia needs to acknowledge people living with dementia as equals. This can be lost even in the well meant phrase ‘dementia friendly communities’.

Change can be intimidating, as it challenges “vested interests”. Both the left and right abhor vested interests, but they also have a strong dislike for abuse of power.

I don’t mean simply ‘involving’ people with dementia in some namby pamby way, say circulating a report from people with dementia, at meetings, or enveloping them in flowery language of them being part of ‘networks’. Incredibly, there is no leader from a group of caregivers in dementia; there are probably about one million unpaid caregivers in dementia in the UK alone, and the current direction of travel for the UK is ultimately to involve caregivers in the development of personalised care plans. It might be mooted that no one person living with dementia can ever be a ‘representative’ of people living with dementia; but none of the people currently on the panel are individually sole representatives either.

I am not accusing the World Dementia Council of abusing their power. Far from it, they have hardly begun to meet yet. And I have high hopes they will help to nurture an innovation culture, which has already started in Europe through various funded initiatives such as the EU Ambient Assisted Living Joint Programmes (“ALLADIN”).

I had the pleasure of working with Prof Roger Orpwood in developing my chapters on innovation in my book “Living well with dementia”. Roger is in fact one of the easiest people I’ve ever worked with. Roger has had a long and distinguished career in medical engineering at the University of Bath, and even appeared before the Baroness Sally Greengross in a House of Lords Select Committee on the subject in 2004. Baroness Greengross is leading the All Party Parliamentary Group on dementia, and is involved with the development of the English dementia strategy to commence next year hopefully.

Roger was keen to emphasise to me that you must listen to the views of people with dementia in developing innovations. He has written at length about the implementation of ‘user groups’ in the development of designs for assistive technologies. Here’s one of his papers.

My Twitter timeline is full of missives about or from ‘patient leaders’. I feel one can split hairs about what a ‘person’ is and what a ‘patient’ is, and ‘person-centred care’ is fundamentally different to ‘patient-centred care’. I am hoping to meet Helga Rohra next week at the Alzheimer’s Europe conference in Glasgow; Helga is someone I’ve respected for ages, not least in her rôle at the Chair of the European Persons with Dementia group.

Kate Swaffer is a friend of mine and colleague. Kate, also an individual living with dementia, is in fact one of the “keynote speakers” at the Alzheimer’s Disease International conference next year in Perth. I am actually on the ‘international advisory board’ for that conference, and I am hoping to trawl through research submissions from next month for the conference.

I really do wish the World Dementia Council well. But, likewise, I strongly feel that not having a leader from the community of people living with dementia or from a large body of caregivers for dementia on that World Dementia Council is a basic failure of democratic representation, sending out a dire signal about inclusivity, equality and diversity; but it is also not in the interests of development of good innovations from either research or commercial application perspectives. And we know, as well, it is a massive PR fail on the part of the people promoting the World Dementia Council.

I have written an open letter to the World Dementia Council which you can view here: Open letter to WDC.

I am hopeful that the World Dementia Council will respond constructively to our concerns in due course. And I strongly recommend you read the recent blogposts on the Dementia Alliance International website here.

Lots of small gains will see our shared vision for living better with dementia shine through

When I asked Charmaine Hardy (@charbhardy) if she would mind if I could dedicate my next book, ‘Living better with dementia’ to her, I was actually petrified.

Obviously, Charmaine had every right to say ‘no’. You see, I met Charmaine through Beth on Twitter, and I saw the three letters ‘PPA’ in Charmaine’s Twitter profile. Charmaine’s Twitter timeline is simply buzzing with activity. It’s hard not to fall in love with Charmaine’s focused devotion everywhere, nor with how much she adores her family. This passion, despite daily Charmaine working extremely hard, itself generates energy. People are attracted to Charmaine, as she never complains however tough times get. She thinks of ways to go forwards, not backwards, even when she had trouble with her roses recently. She basically creates a lot of good energy for all of us. As Charmaine’s Twitter profile clearly states, “I’m a carer to a husband with PPA dementia.”

Things are not right with the external world though. We have millions of family unpaid caregivers rushing around all the time, trying to do their best. Seeing these relationships in action, as indeed Rachel Niblock and Louise Langham must do at the Dementia Carers’ Call to Action (@DAACarers), must be a fascinating experience. There’s a real sense of shared purpose, often sadly against the “system”.

Contrary to popular opinion, perhaps, I have a strong respect for the hierarchy I find myself in. I have asked Prof Alistair Burns (@ABurns1907), a very senior academic in old age psychiatry, to write one of my Forewords. He also happens to be England’s lead for dementia, but I hope to produce my book as a work of balanced scholarship, which does not tread on any policy toes.

But underlying my book is a highly energised social network (@legalaware), based on my 14000 followers on Twitter. My timeline is curation of knowledge in action, in real time as my #tweep community actively share knowledge on a second-by-second basis. There’s a real change of us breaking down the barriers, and changing things for the better. Sure, some things of course don’t go to plan, but with innovation you’re allowed to crack a few eggs to make an omelette. I have enormous pleasure in that in this network people on the whole feel connected and with this power might produce a big change for the better.

My new book is indeed called ‘Living better with dementia: champions challenging the boundaries‘ – and I feel Kate Swaffer (@KateSwaffer) and Chris Roberts (@mason4233) are doing just that. They continually explain, reasonably and pleasantly, how the system could be much improved from their perspectives of living well with dementia, such that we could end up with a ‘level playing field’. And of course the fact we know what each is up to, for example pub quizzes or plane flights, means that we end up being incredibly proud even if we have the smallest of wins.

My proposed contents of this book are as follows: here.

I am not going to write a single-silo book on living better with dementia, however much the medics would like that.

For many of us in the network, dementia is not a ‘day job’. This shared vision is not about creating havoc. It’s simply that we wish the days of the giving the diagnosis of dementia as ‘It’s bad news. it’s dementia. See you in six months’, as outnumbered. That’s as far as the destruction goes. We want to work with people, many of whom I used to know quite well a decade ago, who felt it was ‘job done’ when you diagnosed successfully one of the dementias from seeing the army of test results. I would like the medics and other professionals not to kill themselves over our urge for change, and work with us who believe in what we’re doing too.

Whenever I chat with Kate and Chris, often with a GPS tracker myself in the form of Facebook chat, I am struck by their strong sense of equity, fairness and justice. And I get this from Charmaine too. The issue for us is not wholly and solely focused on how a particular drug might revolutionise someone’s life with dementia. The call for action is to acknowledge friends and families need full help too, and that people living with dementia wish to get the best out of what they can do (rather than what they cannot do) being content with themselves and their environment. We’re looking at different things, but I feel it’s the right time to explain clearly the compelling message we believe in now.

These values of course take us to an emotional place, but one which leads us to want to do something about it. For me, it’s a big project writing a massive book on the various contemporary policy strands, but one where I’ve had much encouragement from various close friends. For me, the National Health Service kept me alive in a six week coma, taught me how to walk and talk again, when I contracted meningitis in 2007. As I am physically disabled, and as my own Ph.D. was discovering an innovative way of diagnosing a type of frontotemporal dementia at Cambridge in the late 1990s, I have a strong sense of wishing to support people living with dementia; especially since, I suspect, many of my friends living well with dementia will have experienced stigma and discrimination at some time in their lives.

I understand why medics of all ranks will find it easier to deal with what they are used to – the prescription pad – in the context of dementia. But I do also know that many professionals, despite some politicians and some of the public press, are excellent at communicating with people, so will want to improve the quality of lives of people who’ve received a diagnosis. We need to listen and understand their needs, and build a new system – including the service and research – around them. I personally ‘wouldn’t start from here’, but this sadly can be said for much for my life. Every tweet on dementia is a small but important gain for me in the meantime. Each and every one of us have to think, ultimately, what we’ve tried to do successfully with our lives.

Suggested reading

Read anything you can by @HelenBevan, the Chief Transformation Officer for the NHS.

Her work will put this blogpost in the context of NHS ‘change’.

Our new white paper is finally out! “The new era of thinking & practice in change & transformation”. Download at http://t.co/83ZFUO1z99

— Helen Bevan (@helenbevan) July 5, 2014

If you say ‘no decision about me without me’ too much, it’ll become meaningless

It seems to have become a ‘bomb proof mantra’.

No self-respecting policy wonk on the healthcare circuit can be seen without the words ‘no decision about me without me’ stitched into the lapel of their jackets.

But if you repeat something enough times, people will believe you.

Conversely, it might become meaningless.

It of course is motherhood and apple pie, and not an ethos which you could fundamentally disagree with. Normally, that is.

This current parliament saw parliament introduce section 75 of the Health and Social Care Act (2012), and its associated regulations. It was a significant departure from previous statutory instruments enacted under previous governments.

This current Government wish to demonstrate in flashing lights their commitment to ‘localism’. This plainly became very hollow when Jeremy Hunt saw fit to contest the Lewisham case in both the High Court and Court of Appeal, against the loud wishes of stakeholders, at taxpayers’ expense.

The NHS in England is still reeling from this catastrophic policy decision, touted by a number of high profile think tanks and their corporate masters. It gave rocket boosters to competitive tendering to the private sector.

In any market, there are winners and losers. For every winner, there’s a loser. There’s a finite amount of cake we are being told. So in this climate it is no wonder that providers, including social enterprises, wish to seek an unique selling point in marketing.

The slogan “no decision about me without me” happily trips off the tongue for the purpose. There is very hard for any reasonable person to argue against the design of research programmes and the service without the views of the end-users.

But this all depends on your precise definition of ‘involvement’. For example, I have been successfully living with two chronic long term conditions, physical disability and mental recovery from a severe alcohol dependence. But in this climate of ‘co-production’ and ‘distributed leadership’, and even shared decision-making, nobody has had the decency to ask me for my opinions about these services.

One can adopt the stance that it is up to me to make my views know, rather than be merely a passive recipient of a service. And of course I do make my views known in non-symbolic ways.

The fact is that patients are all too often liable to made into cannon fodder for other people’s purposes. This might to be to sell a product or service in dementia.

Or they could be used to promote how wonderful ‘community services’ are in a London borough, for the personal gain of those promoting them, but at the expense of shifting resources away from severely under-resourced secondary care hospital units.

And not all stakeholders can be correct, and have an equal say in strategy. Reams and reams and reams have been written on this in the field of ‘corporate social responsibility’. For example, some social enterprises have found real difficulty in rationalising the drive to maximising shareholder dividend with community value and outcomes, however so defined.

And how corporates show responsibility (or rather “don’t behave badly”) has become a hotbed for corporate strategists. For example, Prof Michael Porter, a strategy Chair at the Harvard Business School, published a highly influential review with Mark Kramer on society and strategy.

Large charities – operating strategically in a corporate-like manner – can, it can be argued under this construct, be obtaining their “moral fitness to practise” by involving people they raise large funds for in their mission, whether that is for ‘friendly communities’, ‘care’ or ‘research’.

So the pen is indeed mightier than the sword. Like pornography though, I can recognise real involvement and empowerment when I see it.

Some people aspiring, rather than battling or fighting, to live with dementia do wish to have ownership and control their dreams.

But in this crazy world of ‘dyadic relationships’, and other similar convoluted terms, some persons with dementia for example have their own beliefs, concerns and their expectations. They are not joined at the hip to the carers.

“No decision without me about me” is one of the latest political catchphrases in relation to the health service, in our jurisdiction, and describes a vision of healthcare where the patient is – if not an equal partner – then certainly an active participant in treatment decisions.

In 2002 the independent Wanless report recommended that, in order to cope with rising demand and costs, the NHS should move to ensure that all patients were “fully engaged” in managing their health status and healthcare.

It has a laudable aim, but, like many of these slogans, is at real danger of trivialising what is a profoundly serious policy issue.

Simon Stevens. Is it not where you’ve come from, but where you’re going to?

The new NHS England Chief Executive is Simon Stevens.

Hailed as a ‘great reformer’, the first accusation for Simon Stevens is that he has been parachuted in to change the culture of the NHS. For all the recognition of patient leaders and home-grown leaders in the NHS Leadership Academy, it is striking that NHS England has made an appointment not only from outside the NHS but also from a huge US corporate. Indeed, Christina McAnea, head of health at the union Unison, told the Today programme on BBC Radio 4: “I am surprised that they haven’t been able to find someone within the NHS.”

A person like Stevens is likely to bring a breadth of managerial experiences, although he has never done a hospital job. He is no expert in land economy either. Despite the drama, the transition of the NHS to a neoliberal one has been on a fairly consistent course, as I explained previously in a now quite famous blogpost. I have also discussed how competition was introduced as a major plank in the Health and Social Care Act (2012) despite the overwhelming evidence against its implementation, known at the time; and how the section 75 and associated regulations would be the mechanism to achieve the ‘final blow’ for liberalising the NHS market. Where possibly English health policy experts have failed, perhaps, in their overestimation of the predeterminism that has taken place in England’s health policy since 1997. Changes of government have brought with it various changes in emphasis, such as the Blairite need to ‘reform public services’, possibly away from a socialist centre of gravity. The changing health policy has also had to take on board changes in politics, economics and legal considerations in the last few decades.

The suggestion that NHS England could have chosen ‘a more socialist CEO’ in itself is fraught with criticisms. Can you ‘a bit’ socialist or ‘half socialist’? Indeed, can you implement a ‘socialist NHS’ without implemented a sharing of resources across various sectors, including education or housing? People who don’t wish to engage with such arguments often end up with extremist Aunt Sally arguments referring to socialism as a state like pregnancy or like a religion, but the ideological question still remains can you have state provision of the NHS on a sliding scale from 0-99% private provision? With the current debate about whether Labour would renationalise the railways, in light of the fact that monies are potentially found out of nowhere for foreign military strikes at the drop of a hat, this discussion has never been more relevant potentially. One of David Cameron’s famous phrases, somewhat ironic given his background at Eton and Oxford, is, apparently: “It’s not where you’ve come from – it’s where you’re going to.” This may apply to not only Stevens but the whole of NHS England, especially if you hold the alternative viewpoint that the NHS could and/or should jettison its ‘founding principles’.

It is all very easy to play the ‘man’ not the ‘ball’, and certainly NHS England already has its strategic goals. Nonetheless, it is critically important for any organisation, particularly the NHS, to think about how much of its strategic aims have to be driven from the very top. Attention has turned to the US company he has spent the last decade with as a senior executive: United HealthCare. There is no point, however, being necessarily alarmist. Pro-NHS campaigners will be mindful of this now largely discredited campaign. Resorting to such emotive messaging may distort the genuine discussion which needs to be had about the future of the NHS in England.

Mr Stevens, 47, was Tony Blair’s health advisor between 2001 and 2004, and before that advisor to then-health secretary Alan Milburn. Simon Stevens’ CV reveals that he was a Trustee from The Kings Fund, London (a health charity) between 2007 – 2011 after being a Councillor for Brixton, south London London Borough of Lambeth 1998 – 2002 (4 years). It has even been alleged that Stevens has been a member of the Socialist Health Association. The NHS budget has been notionally protected – it is rising 0.1% each year at the moment – the settlement still represents the biggest squeeze on its funding in its history. Labour has criticised previously how the Coalition has misrepresented the current state of NHS spending. The currently chief executive of the English NHS, David Nicholson, recently called for politicians to be “completely transparent about the consequences of the financial settlements” for the NHS. Nicholson’s point perhaps was that, although politicians say the NHS has been protected financially, this was only relative to real cuts in other areas of government and, crucially, not in terms of the demands on healthcare.

A clue as to how Mr Stevens will run the NHS could be seen earlier this year when he co-authored a report for UHC arguing that the Obama administration could save $500bn in Medicare and Medicaid funding over the next 10 years by more aggressively coordinating medical care for pensioners and the poor. This pitch will have been very attractive to Sir Malcolm Grant. Mr Stevens said instead of concentrating on either cutting benefits or cuts to doctors and hospitals, the US healthcare debate should focus on a “third way”: cutting costs while improving care. A similar challenge awaits him at the NHS. However, the Keogh mortality report identified that safe staffing was a pivotal reason why NHS Trusts had failed un basic patient safety. Stevens is definitely unlikely to find a “third way” between balancing budgets to provide unsafe clinical staffing levels and adequate patient safety.

Some ministers have repeatedly praised Blair’s attempts to reform services, in the earlier period of their administration. In a speech to the Tory party conference earlier this month, Jeremy Hunt highlighted the efforts of Mr Blair and Mr Milburn to increase the use of the independent sector to reduce waiting times. However, Mr Stevens is also associated with the introduction of NHS targets, and helped create the key plan which brought them in. This NHS “target culture” which have been repeatedly attacked by the Coalition as playing a part in scandals such as that at Mid-Staffordshire, as a root cause of the ‘bully boy’ tactics (allegedly) by some NHS CEOs to achieve Foundation Trust and receive personal bonuses. Particularly important then for Labour is not where it has come from but where it is going to.

Andy Burnham MP, Shadow Secretary of State for Health, has repeatedly stated that a Labour Government will repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2012) in its first Queen’s Speech in 2015. It has also been made clear that Labour will do this, even if Burnham is recruited laterally to a different job. For any corporate strategy, a number of drivers will be essential to remember: for example environment, socio-cultural, technological, legal and economics. With the appointment of Stevens “just in time” for the privateers – quite possibly, it is still remarkable that working out the legal niceties of working out ‘mission creep’ in the special administrator powers of NHS configurations is ‘work in progress’. Only this week, it was reported that the Royal Colleges of Physicians have genuine concerns about whether other amendments to the Care Bill are in the patients’ interest, pursuant to the current high-profile mess in Lewisham. Both Stevens and Grant are fully aware that they will have to deal with the political landscape, whatever that is, on May 8th 2015 and afterwards.

Strategic demands of the NHS

Currently NHS England has a number of powerful strategic demands, which could even appear at first blush inherently contradictory. For example, a purpose of patient safety management will be to minimise risk of harm to patients, whereas successful promotion of innovation can be achieved through encouraging risk taking in idea creation. Whatever Stevens’ ultimate vision – and this is why the implementation of Health and Social Care Act (2012) has been so cack-handed – it is essential that industry-acknowledged frameworks for change management are considered at the least. For example, in Kotler’s model of change management, the leader (Stevens) will not only have to ‘create a powerful vision’ but ‘communicate the vision well’.

Patient safety

There is no doubt that the Mid Staffs scandal was a very low point in the NHS. But there’s nothing like a good scandal for focusing the mind? In a general article in June 2009 by James O’Toole and Warren Bennis in the Harvard Business Review (“HBR”), the authors that no organisation could be honest with the public if it’s not honest with itself. This simple principle has been slow to come into the English law, though it has been introduced as an amendment in the Care Bill (2013). A notion has arisen that members of senior management turn a blind eye to failings deliberately (“wilful blindness“), but interestingly the authors draw on the work on Malcolm Gladwell. In his recent book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell had reviewed data from numerous airline accidents. Gladwell remarks, “The kinds of errors that cause plane crashes are invariably errors of teamwork and communication. One pilot knows something important and somehow doesn’t tell the other pilot.” The question is, necessarily, what a CEO can do about it. The authors propose two solutions inter alia. One is to “reward contrarians”, arguing that an organisation won’t innovate successfully if assumptions aren’t challenged. The authors advise organisations, to promote a ‘duty of candour’, to find colleagues who can help, who can be promoted, and who can be publicly thanked. The authors also advise finding some protection for whistleblowers: this might even include people because they created a culture of candour elsewhere. Initiatives such as the Nursing Times ‘Speak Out Safely’ are likely to be highly influential in catalysing a change, but a lot depends on the legal protection for whistleblowers given the current perceived inadequacies of the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998.

There is a growing realisation of implementation of patient initiatives has to be ‘top down’ as well as ‘bottom up’. For example, for Diane Cecchettini, president and CEO of MultiCare Health System, Tacoma, Washington, the key to patient safety has been achieved through leader engagement. She has developed an over-arching strategic framework for quality and safety that has served as the catalyst for the development of multi-year strategic quality and safety improvement plans throughout the MultiCare Health organisation.

Innovation

Innovation is another thorny subject. Innovation (and integration) is always going to be on a dangerous path if primarily introduced as an essential ‘cost cutting measure’, rather than bringing genuine value to the healthcare pathways. Nonetheless, the issue of financial sustainability of NHS England is a necessary consideration, even if the term ‘sustainability’ is open to abuse as I argued previously.

Innovation means different things to different people. As there is no single authoritative definition for innovation and its underlying concepts, including the management of innovation, any discussion on the topic becomes difficult and even meaningless unless the parties to the discussion agree on some common terminology. Innovation requires breaking away from old habits, developing new approaches, and implementing them successfully. It is an ongoing, collaborative process that needs considerable teamwork and skilled leadership. CEOs’ ability to lead their top management team successfully may provide the guidance and inspiration needed to support others to overcome obstacles and innovate. CEOs must provide effective leadership for top management teams to help organizations innovate.

It has been argued that, “There is no innovation without a supportive organisation”. Reviewed in the “International Journal of Organizational Innovation” by de Waal, Maritz, and Shieh (2010), innovation scholars have proposed numerous factors that, to a greater or lesser degree, have the potential to make organisations more conducive to innovation:

- A culture that encourages creative thinking, innovation, and risk-taking

- A culture that supports and guides intrapreneurial liberty and growing a supportive and interconnected innovation community

- Cross-functional teams that foster close collaboration among engineering, marketing, manufacturing and supply-chain functions

- An organisation structure that breaks down barriers to innovation (flat structure, less bureaucracy, fast decision-making, etc.)

- Managers at all levels that support innovation

- A reward system that reinforces innovative and entrepreneurial behaviour

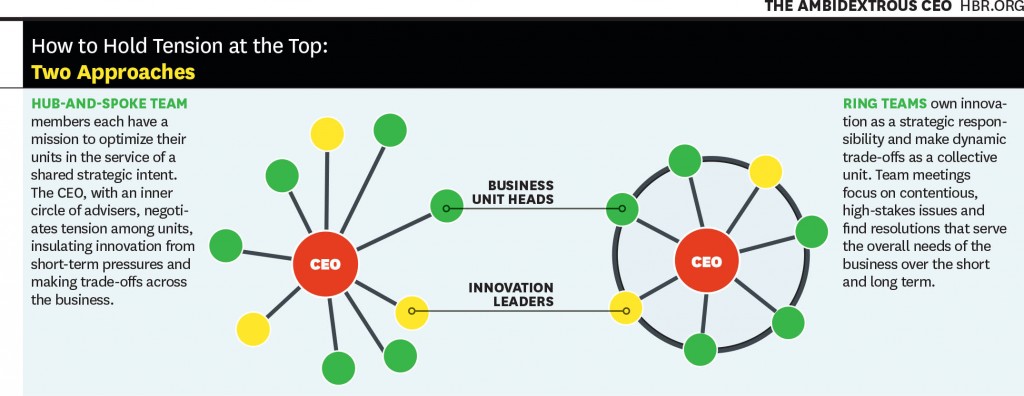

Communicating the vision, as described earlier, is also important for innovation management. This is a potential problem with KPMG’s Mark Britnell’s thesis of how raising the private income cap could promote innovation, as NHS and private wards nearly always co-exist in separate hospitals in ‘NHS Trusts’. It is argued in an interesting article in the Harvard Business Review (2011) entitled, “The ambidextrous CEO”, conflicts in innovation management are best resolved at the very top, and this could be filtered to the rest of the organisation through models such as “hub and spoke”.

It’s probably fair to say that a lot actually rests on the shoulders of CEOs in how innovative they wish their organisation to become. And certainly the ‘high-profile transfer of CEOs’, almost akin to the transfer of footballers, has attracted considerable recent interest, such as Burberry’s Angela Ahrendts joining Apple.

Thomas D. Kuczmarski in a rather sobering paper entitled, “What is innovation? The art of welcoming risk” identifies the CEO even as a potential ‘barrier-to-innovation’ (as far back as in 1996):

If you are like most CEOs, you are in a state of denial. Most CEOs express a fervent belief in new ideas and claim to be committed to innovation, but actions speak louder than words.

The truth is that most CEOs and senior managers are intimidated by innovation. Viewing it as a high-risk, high-cost endeavor, that promises uncertain returns, they are afraid to become advocates for innovation. However, because it clearly represents challenge and opportunity, most CEOs deny their reluctance to embrace innovation. They deny that their new product programs are underfunded or understaffed. They deny that they are closed to new ideas or ways of doing business. They deny that they fail to encourage or reward innovative thinking among their employees. Most of all, they deny that they have created within their organizations a fear of failure that stymies the urge to innovate.

All this denial is not good. It sends mixed messages throughout the organization and sets up the kind of second-guessing and playing politics that can undermine even the best developed business strategies. Unwilling to be measured by their failures, employees are reluctant to take risks that the successful development of new ideas demands and, as a result, even the desire to innovate diminishes.

Stevens (2010) himself has publicly expressed concerns on failure to innovate. For example, in the Harvard Business Review, he discussed how information on new clinical treatments spreads across the world quite fast, and how healthcare systems which fail to be flexible enough on picking up on this are likely to fail. Stevens’ example is striking:

However, the rate at which innovations are being translated into actual improvements is agonizingly slow — a frustrating problem that dates back to the world’s first controlled clinical trial in 1754. It proved that lemons prevented sailors from getting scurvy, but it then took another 41 years for a navy to act on the results. Wind the clock forward to today, and 15 years or so after e-mail became common, it turns out that most patients still can’t communicate with their doctors that way.

Deutsch (1973, 1980) proposed that how individuals consider their goals are related, very much affects their dynamics and outcomes. The basic premise of the theory is that the way goals are structured affects how people interact and the interaction pattern affects outcomes. Goals may be structured so that people promote the success of others, obstruct the success of others, or pursue their interest without regard for the success or failure of others. Deutsch identified these alternatives as cooperation, competition, and independence. In cooperation, people believe that as one person moves toward goal attainment, others move toward reaching their goals. They understand that others’ goal attainment helps them; they can be successful together. In competition, people, believing that one’s successful goal attainment makes others less likely to reach their goals, conclude that they are better off when others act ineffectively. When others are productive, they are less likely to succeed themselves. They pursue their interests at the expense of others. They want to ‘win’ and have the other ‘lose’. With independent goals, people believe that their effective actions have no impact on whether others succeed. Researchers have long debated whether cooperation or competition is more motivating and productive (Johnson, 2003). As regards the thrust of what happens in reality following 2015, therefore, the political landscape does very much happen. If Labour wish to promote collaboration perhaps through integration of health and social care, the entire nature of this dialogue will change. And the new CEO of NHS England will have a pivotal rôle in the organisational learning of the whole of NHS England.

Further implications for Labour in general policy