Home » Posts tagged 'Kate Swaffer'

Tag Archives: Kate Swaffer

Stigma in dementia poses crucial questions for dementia friendly communities

The literature on stigma is comprehensive.

But Kate Swaffer added to it beautifully in the journal ‘Dementia’, with an article today – on open access – entitled “Dementia: Stigma, language and dementia friendly”.

Kate refers to a blogpost by Ken Clasper, a Dementia Friends Champion, which asks, sensibly, what we are trying to achieve with more ‘awareness’.

And if you scroll down to the end of this tour de force on stigma and dementia, you’ll see exactly why Kate is able to opine with such legitimacy and authority.

I conceded a long time ago – in March 2014, in fact – on this blog that the policy plank of ‘dementia friendly communities’ is an incredibly complex one.

The discussion of stigma seems to be one of perpetuity. We’ve seen numerous attempts at it, including the original work of Goffman (1963) on stigma and ‘spoiled identity’.

It’s been re-incarnated as a Royal College of Psychiatrists campaign on stigma.

This morning there was another bite of the cherry.

The report, New perspectives and approaches to understanding dementia and stigma, published by the think tank International Longevity Centre UK (ILC-UK) is produced by the MRC, Alzheimer’s Research UK, and Alzheimer’s Society; it was also supported by Pfizer.

I’ve thought how I could possibly respond to Kate. And I can’t, as Kate is in every sense of the word an ‘expert’.

But it did get me thinking.

It got me thinking of the happy times I had with Chris and Jayne last week at the Alzheimer Europe conference in the city of my birth in Glasgow.

‘There’s more to the person than the diagnosis” is one of the key five messages of ‘Dementia Friends’, an initiative from the Alzheimer’s Society predominantly (and Public Health England). This is mirrored in a tweet by Chris from this morning.

Chris is also a “Dementia Friends Champion“, and lives well with dementia.

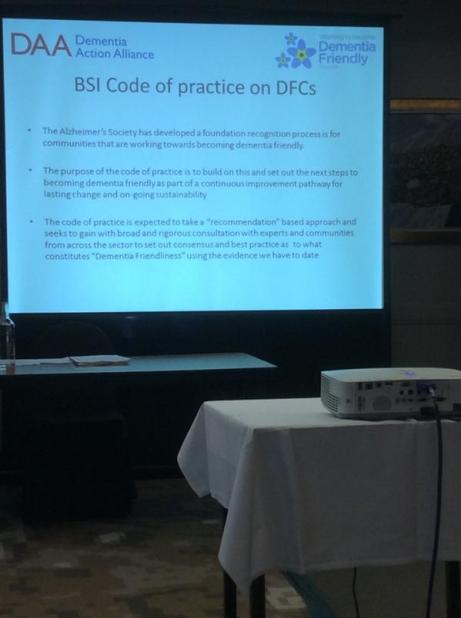

Last week, I attended a brilliant all-day workshop chaired by Karishma Chandaria, Dementia Friendly Communities manager for the Alzheimer’s Society. The progress which has been made on this policy plank is substantial, and I am certain that the next Government will wish to support this policy initiative in the English for 2015-20.

It is stated clearly in Simon Stevens’ “Five Year Plan” for NHS England.

It is a core thread of the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge.

And the ‘coalition of the good’ has seen the dementia friendly communities policy plank develop drawing on work from ‘Innovations in dementia’ and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

And to give the Alzheimer’s Society credit, where it is certainly due, there has been launched an open consultation for a British Code of Practice (currently ongoing), to which anybody can contribute.

But this code of practice does, again, have the potential to be very divisive. It might be painful to make dementia friendly communities, such as the large one in Torbay, ‘fit into this box’.

Torbay in many ways is a beacon of innovation for integration between NHS and care. There is genuine “community bind”, with citizens, shopkeepers, transport, police, for example, contributing.

The article on the BBC website about Norman McNamara (January 2012) predates the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge, (which started in March 2012.)

Any top down way of making bottom-up social groups ‘conform’ will be hugely problematic in the implementation of this approach to dementia-friendly communities, potentially.

The methodology of dementia friendly communities has to be truly inclusive: it is all or nothing.

I agree with Kate, and like her I wish to avoid protracted circular definitions of ‘stigma’. For me, I recognise stigma when you see it, like how the Supreme Court of the US recognises erotica and pornography as per Jacobellis v Ohio [1964].

It is possibly easier to define stigma by its sequelae, such as avoiding wishing to talk about dementia in polite conversation, or not wishing to see your GP about possible symptoms of a dementia in its early stages, or not wanting to socialise with people with dementia who happen to be in your family.

We know these are real phenomena, as demonstrated, for example, by the loneliness of many people on receiving a diagnosis of possible dementia.

And we know stigma can harbour deep-seated irrational prejudice, like the incorrect notion that dementia is somehow contagious like a ‘superbug’.

Stigma can be exhibited in pretty nasty ways in language: such as “snap out of it” or “victim”.

My discussion of whether people living with dementia are ‘sufferers’ tends to go round and round in circles with people who disagree with me.

Suffice to say, I agree it is possible for a person living with dementia, such as a person who has received a diagnosis of Lewy body dementia and who has to put up with terrible “night terrors” and exhaustion the following day.

I think if you live independently, but with full insight into your symptoms, it can be exasperating. I have never been in that position though, and it would be invidious of me to second-guess.

I think if you are close to someone in the latter stages of dementia, you can suffer.

But I’ve written about this all, indeed on this blog, before here.

The only thing that is new is Peanuts’ cartoon (original citation here).

In that workshop, I also sat through Joy and Tone Watson’s brilliant “Dementia Friends” session. Joy lives with dementia. And their session was brilliant.

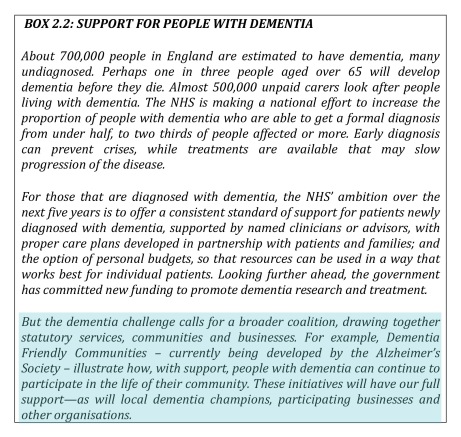

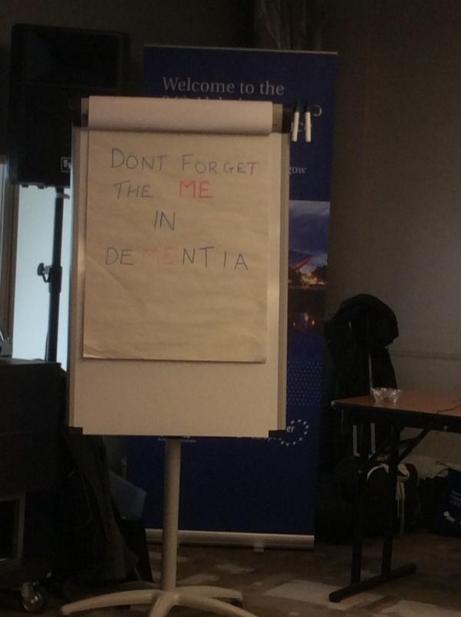

This was the final ‘exhibit’.

I attended a special group session on stigma with Toby Williamson from the Mental Health Foundation during that day. In that session, it was mentioned that ‘rôle models’ of people living well with dementia might help to break down stigma.

Or maybe guidance for the media might help? One cannot help wondering if an article such as in the Daily Mail today might actually put off people from seeking a diagnosis of dementia (completely unintentionally).

But I did bring up something on my mind.

“Stigmata” literally means signs.

But dementia can be, like other disabilities, quite invisible.

Somebody might have insidious change in personality and behaviour, noticed by somebody closest to him or her, with no obvious changes in cognition (nor indeed in investigations).

I showed this in my paper published in Brain in 1999, currently also in the Oxford Textbook of Medicine.

The condition I refer to is in fact one of the more prevalent causes of dementia in the younger age group, called the “behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia“.

If the signs are ‘visible’, then you are obliged legally to make reasonable adjustments for any disability. In England, this includes dementia under the guidance to the Equality Act (2010).

As Toby Williamson says, if you’re obliged to build a ramp for somebody in a wheelchair for a place of work, there’s an equal obligation to produce adequate signage for people who have navigation problems as a result of a dementia such as dementia of the Alzheimer’s type.

There are reams and reams of evidence on equality and the built environment (for example the Design Council or Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment).

I personally think it’s brilliant you can go into certain shops, and the customer-facing staff will, potentially, be able to recognise if a person does need time and space to pay for items.

This is also been tackled in the Scottish jurisdiction through Alzheimer Scotland.

Also, corporate lawyers should be advising large employers about the scope for unfair dismissal claims by people dismissed as they are about to arrive at a diagnosis of dementia (particularly young onset dementia).

The timeline is roughly this. Somebody has health problems – he or she is invited to leave and given a pay off – these health problems turn out to be a diagnosis of probable dementia – by this time the dismissal is not unfair.

I feel confident the ‘dementia friendly communities’ policy strand in England, and across other jurisdictions, is here to stay. I share, though, Kate’s concerns that about the relative ease with which this policy has lifted off, say, compared to how one might feel about ‘gay friendly communities’ or ‘black friendly communities’. One has to be extremely careful about any policy plank which alerts people to divisions, “them against us”.

This is what I know best as the “don’t think of elephants phenomenon” and then you think of elephants.

This policy, anyway, currently has huge momentum. Marc Wortmann is currently Executive Director of Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI), the organisation providing a global voice for dementia and the founder of World Alzheimer’s Month. Wortmann has been instrumental in propelling dementia friendly communities to the foreground of world policy.

But, in firing up ‘dementia friendly communities’ (a term which I think is sub-optimal’), v 2.0, there is plenty of time to get it right.

The 24th Annual Conference for Alzheimer Europe put people with dementia in the driving seat. Deservedly so.

The biggest dementia conference to be taken place in Scotland (“Conference”, attended by 800 professionals, people with dementia and carers) was held in Glasgow last week (20-23 October 2014).

The focus of the conference was Dignity and autonomy in Dementia and the four day event explored in quite some detail how recognising the human rights of people with dementia, their carers, partners and families is key to ensuring dignity and respect, as well as overcoming stigma.

It was the 24th Annual Conference of Alzheimer Europe (@AlzheimerEurope, an umbrella organisation of 36 Alzheimer associations from 31 countries across Europe), supported this year by Alzheimer Scotland, .

The timetable was exacting.

The people there were very special; for example Tommy Whitelaw (@TommyNTour) mentioned in Alex Neil MSP’s speech at the conference. Tommy and Irene Oldfather (@IreneOldfather) happened to be passing through during one of my poster sessions.

And Beth Britton (@BethyB1886).

Well done to the conference organisers for putting it together, especially Gladwys Guillory.

The main conference hall of the venue, the Crowne Plaza in Glasgow, the Argyll Suite, was majestic.

I particularly liked the ‘live Twitter feed’ at the front of the hall, where curiously Kate Swaffer (@KateSwaffer) appeared many times all the way from Australia. Here I am appearing with my ‘selfie’, with somebody well known in the foreground of the photograph.

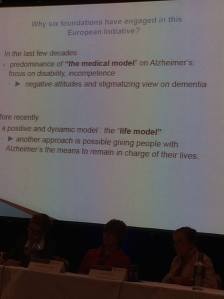

The relative failure of the medical model in addressing the needs of people with dementia and caregivers was a pervasive theme throughout the whole conference.

I had a nice chat with Marc Wortmann (@marcwort) over one of the lunches. Marc is in charge of all aspects of ADI’s work (ADI = Alzheimer Disease (and associated conditions) International; @AlzDisInt). Collaborating with the Board, Marc implements finance and campaign strategies.

Marc represents ADI at international conferences and in the NCD Alliance and takes part in WHO and UN meetings. I was also able to bump into Jean Georges (@JeanGeorgesAE), the Executive Director of Alzheimer Europe.

Cabinet Secretary for Health, Alex Neil, delivered a clear keynote speech to the conference at the Tuesday morning plenary session, in which he paid tribute to the immense contribution of Tommy Whitelaw.

Key to the event was the signing of the Glasgow Declaration: a commitment to promoting the rights, dignity and autonomy of people living with dementia across Europe, as guaranteed in the European Convention of Human Rights and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Here’s a great slide of @alzscot‘s “PANEL” (pic taken by @LauraMcC86).

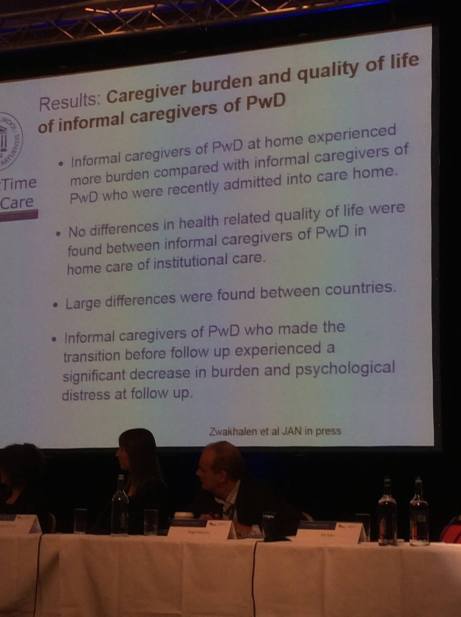

The satellite symposium sessions were well put together, and attracted substantial audiences.

There was an amazing moment when Agnes Houston (@Agnes_Houston), Chair Scottish Dementia Working Group, said to Helga Rohra (@ContactHelga), the Chair of the satellite session and Chair of European Persons With Dementia, “All we people with dementia need is a bit of help — AND A BIT OF TIME!”

A quotation from Agnes – from a previous conference – says it all for me.

The audience burst out laughing.

The reason for this is that Agnes had been originally timetabled to have more time for her slot, apparently.

As the conference was themed around the law, including human rights, invariably discrimination against people with dementia came up in various forms.

I asked about the topic several times.

One talk of the entire programme which I thought was truly outstanding was PL1.3. Gráinne McGettrick (Alzheimer’s Society of Ireland): The UN Disability Convention as an instrument for people with dementia and their carers.

In the English jurisdiction, dementia can count as a disability; therefore there are statutory requirements for ensuring dementia-friendly communities from employers. Also, unfair dismissal of a person on account of being newly diagnosed with dementia will clearly be unlawful.

A member of the audience politely pointed out to me afterwards that a person normally gets sacked first, and then gets his or her diagnosis of dementia confirmed much later, so at the point of dismissal the dismissal does not obviously appear unfair legally.

I found this observation incredibly insightful, as there have been thus far no ‘test cases’ of unfair dismissal on grounds of a diagnosis of dementia in the English jurisdiction.

I had brought along my book ‘Living well with dementia’, but I rarely got a chance to read (or refer) to it during the course of the whole week!

I asked several times why there is no representative of persons living with dementia or caregivers on the World Dementia Council (@WorldDementia). The background to this fiasco is explained here.

I had designed that I would be staying in the same competitively-priced hôtel as Jayne Goodrick (@JayneGoodrick) and Chris Roberts in Glasgow for the 24th Alzheimer Europe conference held in Glasgow, the city where I was born.

It was by chance we gave a lift to Dr Ruth Bartlett (@RuthLBartlett) to the conference venue. Ruth was staying, as it turns out, in the same competitively-priced hôtel.

Ruth is of course well known for her well respected contributions about the citizenship of of people living with dementia, and how this has influenced the ‘involvement’ of people with dementia in policy.

This was us just before the opening ceremony – when we were full of energy.

I really enjoyed speaking with Geoff Huggins (@GeoffHuggins), who gave an excellent speech in the opening ceremony.

I presented my talk on how dementia healthcare would not be best served by a private insurance system, because of the potential problems of ‘moral hazard’ and genetic discrimination.

This talk was, overall, well received.

I was particularly pleased with the wide-ranging, excellent discussion we had after my talk. Thanks especially to Amy Dalyrymple (@Amy_Dalyrymple), Head of Policy for Alzheimer Scotland, whose contributions in all areas of policy were particularly interesting. The work currently being implemented in Scotland represents a culmination of very high quality inclusive work through a number of different stakeholders.

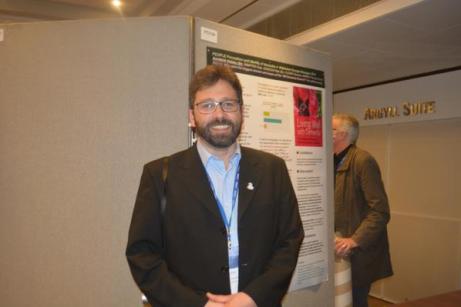

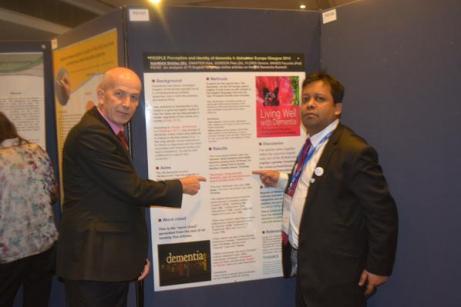

I was also honoured to present two further research posters, which I had co-authored on the perception and identity of the G8 conference.

And here’s co-author Dr Peter Gordon (@PeterDLROW) proudly in front of our poster too!

Chris Roberts (@mason4233) helped me with the poster session. It was in fact Chris who identified that the phrase “living well with dementia” was not used even once in the top 75 web articles on #G8dementia on Google, in about 44000 words odd.

All around the conference were people whose work is directly relevant to my book: for example Silke Kammer – on the arts and music – and Emma Killick (@RealEmmaKillick) who at the excellent MacIntyre leads on children and adults with learning disabilities and/or autism, but is clearly passionate about people with learning disabilities who later have further unaddressed needs on receiving a diagnosis of dementia.

It was terrific to bump into followers everywhere I went. It was great to meet Julie Christie (@juliechristie1) for the first time, whose work on resilience I am much interested in. It was also lovely to see Anna Tatton (@annatatton1) doing so well.

I am well aware of why the Scottish dementia nursing strategy, some say, has become the ‘envy of the world’. It was a huge privilege to meet in person Janice McAlister (@JaniceMcAlister), who was BJN Nurse of the Year Elderly Care 2013. In addition, I found the presentation by Hugh Masters (@HughCMasters), Associate Chief Nursing Officer for the Scottish Government, interesting for insights as to how England might improve its service too.

I happened to meet in the foyer of the Crowne Plaza on Monday night Ann Pascoe, @A_Carers_Voice, somebody who I have not only liked a lot on Twitter, but whose work on rural ‘dementia-friendly communities’ I have massively respected for some time.

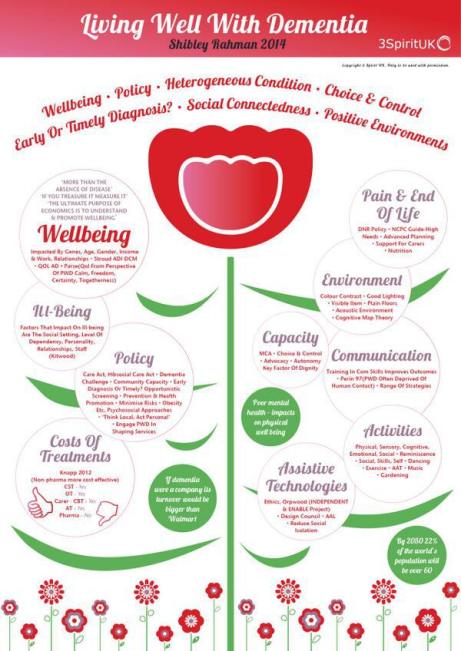

Likewise, it was really nice to catch up with Caroline Bartle (@3SpiritUKNZ), who very kindly once did an infographic of my book ‘Living well with dementia’.

I met in the poster session Prof Mary Marshall to whom the Stirling School in design in dementia owes a huge amount. I owe a huge amount to Prof Marshall too, as the Notting Hill masterclass which I once attended got me first interested in this subject a few years ago (I had a long chat with Prof Marshall there.)

There were not idle tokenistic sops to people living with dementia, and their closest ones, in the whole conference. They were at all times integral to the fabric of the conference.

For example, the seating arrangements in the main Argyll conference suite reflected the special respect given to people with dementia and those closest to them.

The substance of the conference for the most part was of an exceptionally high standard in policy; there was next to no shilling of commercial projects.

The work from Alzheimer Scotland (@alzscot), including, predictably, the work focused on autonomy and dignity, and human rights, was showcased in an impressive way. Their work hangs together as a coherent, forceful narrative of meaningful significance for the Scottish jurisdiction.

It also has clear implications for how England conducts itself south of the border, notably, for example, in a right to timely diagnosis, and a right to timely care and support (including proper coordination of care and support).

In common with Scotland, England is trying to tackle hard the inappropriate use of antipsychotics. Dr Karim Saad (@KarimS3D) gave an excellent talk on this subject, drawing on recent findings from the ALCOVE2 study.

Scotland, in fairness, seems to be having less trouble with its policy than England is.

There was a very good sprinkling of cutting-edge research relevant to all practitioners in the field.

For me, the conference had the feeling of a happy wedding without any of the arguments.

Here are Agnes and Donna.

Whilst originally ‘unkeen’, I ended up having a wonderful time at the “Gala Dinner”. The entertainment – traditional Scottish music and dance – was amazing.

I was able to chat with Agnes and Nancy for some time. What a joy.

Elaine Hunter (@ElaineAHPmh) gave an excellent presentation on the transformative changes which had happened around the workforce in Scotland, including leadership from allied health professionals.

Without doubt, a skilled workforce for the provision of dementia services is essential, not gimmicks.

I consider Helga to be a true friend too. Meeting Helga was akin to being wowed by Lady Gaga.

I had last felt like this when I met Norman McNamara (@norrms) at the Queen Elizabeth II centre in London, Westminster.

I learnt a lot from the all-day workshop on building dementia friendly communities.

Over lunchtime, Joy Watson gave a brilliant ‘Dementia Friends’ (@DementiaFriends) session. I, in fact, was total awe as I am also a ‘Dementia Friends Champion’, and discovered many tips how to run my sessions in future!

This is a brilliant film exhibiting the passion which Joy puts into her Dementia Friends sessions.

Karishma Chandaria (@Karishma1000) chaired this exceptional day’s workshop, called a ‘masterclass’ on dementia friendly communities, which indeed mentioned the code of best practice for dementia friendly communities currently under consultation.

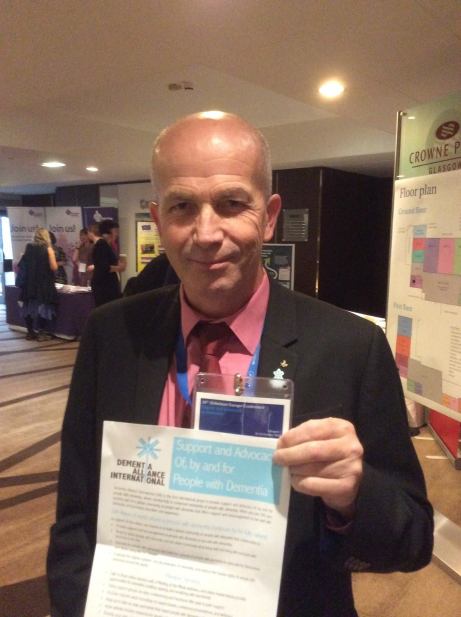

Chris Roberts made time to hand out flyers for membership of the ‘Dementia Alliance International‘, an unique campaigning group run wholly by people living with dementia.

This Conference mapped topics clearly onto people living with dementia and caregivers, for which the organisers of this event must be heavily congratulated.

Next year’s Conference will be in Slovenia. I’ll be there! Bring it on!

The World Dementia Council will be much stronger from democratic representation from leaders living with dementia

There is no doubt the ‘World Dementia Council’ (WDC) is a very good thing. It contains some very strong people in global dementia policy, and will be a real ‘force for change’, I feel. But recently the Dementia Alliance International (DAI) have voiced concerns about lack of representation of people with dementia on the WDC itself. You can follow progress of this here. I totally support the DAI over their concerns for the reasons given below.

“Change” can be a very politically sensitive issue. I remember going to a meeting recently where Prof. Terence Stephenson, later to become the Chair of the General Medical Council, urged the audience that it was better to change things from within rather than to try to effect change by hectoring from the outside.

Benjamin Franklin is widely quoted as saying that the only certainties are death and taxes. I am looking forward to seeing ‘The Cherry Orchard” which will run at the Young Vic from 10 October 2014. Of course, I did six months of studying it like all good diligent students for my own MBA.

I really sympathise with the talented leaders on the World Dementia Council, but I strongly feel that global policy in dementia needs to acknowledge people living with dementia as equals. This can be lost even in the well meant phrase ‘dementia friendly communities’.

Change can be intimidating, as it challenges “vested interests”. Both the left and right abhor vested interests, but they also have a strong dislike for abuse of power.

I don’t mean simply ‘involving’ people with dementia in some namby pamby way, say circulating a report from people with dementia, at meetings, or enveloping them in flowery language of them being part of ‘networks’. Incredibly, there is no leader from a group of caregivers in dementia; there are probably about one million unpaid caregivers in dementia in the UK alone, and the current direction of travel for the UK is ultimately to involve caregivers in the development of personalised care plans. It might be mooted that no one person living with dementia can ever be a ‘representative’ of people living with dementia; but none of the people currently on the panel are individually sole representatives either.

I am not accusing the World Dementia Council of abusing their power. Far from it, they have hardly begun to meet yet. And I have high hopes they will help to nurture an innovation culture, which has already started in Europe through various funded initiatives such as the EU Ambient Assisted Living Joint Programmes (“ALLADIN”).

I had the pleasure of working with Prof Roger Orpwood in developing my chapters on innovation in my book “Living well with dementia”. Roger is in fact one of the easiest people I’ve ever worked with. Roger has had a long and distinguished career in medical engineering at the University of Bath, and even appeared before the Baroness Sally Greengross in a House of Lords Select Committee on the subject in 2004. Baroness Greengross is leading the All Party Parliamentary Group on dementia, and is involved with the development of the English dementia strategy to commence next year hopefully.

Roger was keen to emphasise to me that you must listen to the views of people with dementia in developing innovations. He has written at length about the implementation of ‘user groups’ in the development of designs for assistive technologies. Here’s one of his papers.

My Twitter timeline is full of missives about or from ‘patient leaders’. I feel one can split hairs about what a ‘person’ is and what a ‘patient’ is, and ‘person-centred care’ is fundamentally different to ‘patient-centred care’. I am hoping to meet Helga Rohra next week at the Alzheimer’s Europe conference in Glasgow; Helga is someone I’ve respected for ages, not least in her rôle at the Chair of the European Persons with Dementia group.

Kate Swaffer is a friend of mine and colleague. Kate, also an individual living with dementia, is in fact one of the “keynote speakers” at the Alzheimer’s Disease International conference next year in Perth. I am actually on the ‘international advisory board’ for that conference, and I am hoping to trawl through research submissions from next month for the conference.

I really do wish the World Dementia Council well. But, likewise, I strongly feel that not having a leader from the community of people living with dementia or from a large body of caregivers for dementia on that World Dementia Council is a basic failure of democratic representation, sending out a dire signal about inclusivity, equality and diversity; but it is also not in the interests of development of good innovations from either research or commercial application perspectives. And we know, as well, it is a massive PR fail on the part of the people promoting the World Dementia Council.

I have written an open letter to the World Dementia Council which you can view here: Open letter to WDC.

I am hopeful that the World Dementia Council will respond constructively to our concerns in due course. And I strongly recommend you read the recent blogposts on the Dementia Alliance International website here.

Inspirational people in dementia? I know them when I see them.

My interest in dementia started about 17 years when a graduate student in cognitive neurology at the University of Cambridge.

There’s one thing I can say about brilliant people. They never advertise themselves as brilliant.

Take for example when I showed Prof Trevor Robbins my findings from a group of patients with the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia on a test of ability to switch “cognitive set”.

What’s “cognitive set”?

Say I asked you to think of a colour. “Red”

And another? “Green”

And another? “Blue”

Now tell me the name of a shape.

“Turquoise”

I am unable to shift cognitive set. I am “stuck in set”.

Anyway, it was a bit more complicated than that. I was on the Downing Site in the head of department’s office at the University of Cambridge in 1998.

He said, “That’s amazing!” And then pulled off the top shelf a paper from a journal on psychopharmacology and showed me the virtually same graph from adults who’d been given a ‘low tryptophan drink’. This had depleted a chemical in their brain called serotonin, it’s thought.

That’s brilliant.

Or take another time when I was a hapless junior doctor on Prof Martin Rossor’s dementia and cognitive disorders firm at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery.

I was asked to do the investigations for a man in his 30s who’d presented with a profound change in behaviour and personality over several years, who’d also had some vague memory problems.

I was advised to stick a needle in his back to get some fluid off his spinal cord in virtually a space suit for protection.

I organised the MRI brain scan. I showed it to Dr John Stevens at the National. He said, “You know what is, don’t you?”

“No”

“HIV dementia”

“What does he do out of interest?”

“He’s a lap dancer in Soho.”

That’s brilliant.

You see, I know brilliant people in the dementia arena when I see them, and almost virtually always they never shout about their abilities.

Take for example Kate Swaffer and her brilliant blogpost on dementia and human rights this morning.

Or Beth Britton’s consistent work on raising awareness of issues about caring.

And Ming Ho’s work too. And Darren Gormley’s. And Jo Moriarty’s.

I don’t need book reviews, award ceremonies or conferences to tell me how inspirational or brilliant people are.

I don’t wish to use Twitter for that either.

The phrase “I know it when I see it” was a colloquial expression by which a speaker attempts to categorise an observable fact or event, although the category is subjective or lacks clearly defined parameters.

The phrase was famously used in this sense by United States Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart to describe his threshold test for obscenity in Jacobellis v Ohio (1964).

Dementia is not the same as an obscenity. But the same principles for this test apply, I humbly submit, m’lad.

No one person has taught me more about living well with dementia than Kate Swaffer

When I posted this on my Facebook yesterday

it was on the back of a joke that Chris Roberts and Kate Swaffer, both friends of mine, had GPS trackers on me.

I intend to tackle the potential beneficial use of GPS trackers for some people living with dementia at significant risk of travelling way beyond their local environment.

And travelling beyond my comfort zone is exactly what happened to me at the end of last week.

I ended up at the Alzheimer’s Show in Manchester, to give a 20 minute skit on my book ‘Living well with dementia‘.

Tommy Dunne and Chris Roberts, bosom buddies, sat together in a little section of the workshop. I could spot they were listening to every word.

Jayne Goodrick asked me a gentle question – unlike the question I asked from Prof Stuart Pickering Brown the day previously,

“I’d like to ask Prof Pickering Brown, but this question applies to the rest of the panel too, how the millions spent on Big Data and identifying genetic factors for Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia, like TREM2, can be rationalised in the context of a social care system on its knees, with zero hour contracts and breaches of the national minimum wage?”

I had of course pre-warned the panel that the question would be incomprehensible, as I am disabled.

Jayne said the question was ‘coded’, but Prof Pickering Brown likewise answered in code.

And he took the question well – I had a chance to thank him for all the work he does on frontotemporal dementia, and he asked me to pass on his personal regards to Prof John Hodges.

John is one of THE leading experts in frontotemporal dementia, well respected around the world in academia.

More importantly, he is looking forward to my new book, “Living better with dementia: how champions can challenge the boundaries”.

Chris especially feels, and Tommy agrees, that a much more suitable title would be ‘Living better with dementia.”

Now that Chris has explained it, I completely agree. “Living well with dementia” implies imposition of your judgment as to what living well is.

And whatever your objective level of living might be, nobody can deny a need to live better.

It took me some time to get it, but I did in the end.

A bit like how the penny dropped with Tommy’s joke about urinating with the door open.

But I loved ‘The Alzheimer’s Show’ as it felt truly as if I was amongst friends – and I met people whom I have only met on Twitter, who were truly lovely : Suzy Webster, Natasha Wilson, Chris Roberts, Jayne Goodrick, Tommy Dunne.

And I met some wonderful friends from before: Louise Langham, Carers’ Coordinator for CC2A, and Rachel Niblock.

And I met some brilliant people who’d been following me on Twitter, such as Tracey from CareWatch.

I phoned Nigel Ward, the Show Director, and he was brilliant as usual: “Why did you phone me Shibley? There’s no signal in here, and I was only in the next-door cubicle?”

Anyway, I’ve been on and off in the dementia field for seventeen years, which has taken me on various ups and downs, including three months on the dementia and cognitive disorders firm under Prof Martin Rossor as a junior doctor at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen Square.

It’s also seen me go via a 2 year 10 months PhD at the University of Cambridge. I was the first person in the world to demonstrate reliably risky decision-making behaviour in persons with the behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia. It’s a finding which has been resilient for the last fifteen years, having been replicated and explained through neuroimaging.

I am not really into ‘co-production’, mainly having seen it being used as a cover for legitimising some people’s pre-formed agendas.

But I have been heavily influenced by Kate Swaffer who received a diagnosis of dementia some years ago.

The contents of my new book, to be submitted by the end of October 2014, reflect mutual interests of ours. Kate is more than a cook, former nurse, brilliant blogger, and advocate for Alzheimer’s Australia.

I am honoured she is a close friend of mine. She is not motivated by any narcissistic twang.

She is brilliant.

She has taught me more about dementia than anyone I know.

And it’s her birthday today.

#KoalaHugs

A powerful group led by persons with dementia may be just the disruptive innovation the world needs

This, rather than “The Golden Arches”, is fast becoming a symbol of hope.

The motor vehicle was supposed to be a major disruption for the horse and cart. Paper superseded parchment. The DVD long surpassed the audio cassette.

Progress and innovation, whatever your political philosophy, some might say is pretty inevitable.

In terms of technology, people have recently opined about three ‘industrial revolutions’, and “the shock of the new”.

Innovations can not just be about products. They can be about fundamentally a whole new way of doing things.

The traditional large charity for dementia model has its advantages. It, through economies of scale and large operational efficiencies, can implement large projects, liaise with governments, and have a lot of media backing in the implementation of their projects.

The down-side to this is that it can too easily suffocate innovation from small social enterprises. It can also pursue agendas which are biased in one particular direction.

One example is witnessed in the the appointment of the World Dementia Council.

This Council, quite strangely, does not include any representatives of persons with dementia or representatives of carers. If its primary purpose is to develop new innovations or drugs, they will need to know the efficacy of user adoption at some stage even from a management or industrial basis.

As it is, large charities, in promising to deliver new orphan drugs for dementia one day, can totally ignore the need for high quality research into living well with dementia. They can treat their associated persons with dementia as ‘subjects’ for future drug trials.

This is incredibly problematic and obstructive for those people with dementia – and their supporters including researchers – who wish to pursue an agenda of quality of life in dementia for current people living with dementia.

Even in the press bulletin for the first meeting of the World Dementia Council, dementia is referred to as a ‘timebomb’.

This is incredibly troublesome for some purists who note that the prevalence of dementia across two decades in England may in fact be falling, due to primary care managing successfully the vascular dementias.

So in this specific scenario – a timebomb it is not.

Of course, the ‘holy grail’ for drug companies, and large charities supporting them, is that there exists a ‘pre-dementia’ stage, of people without symptoms, who could be amenable for drug treatment later one day, or advice about lifestyle and risk factors.

Currently, the evidence for the feasibility of this approach is very poor, however.

But something quite amazing, and indeed “disruptive”, happened quite recently. To say it could be explosive for international policy is in fact an understatement.

The 29th International Conference of Alzheimer’s Disease International, entitled “Dementia: Working Together for a Global Solution” held on 1-4 May 2014 at San Juan, Puerto Rico, was beyond reasonable doubt a storming success.

The ADI welcomed Glenn Rees, current CEO of Alzheimer’s Australia, as its Chair-Elect. This is a highly significant appointment, and one which people who promote the living well with dementia philosophy extremely warmly welcome.

So what?

A plucky group of people with dementia emerged, gave talks, and presented cutting-edge research. It was no longer a case of ‘listening to people with dementia’, but rooms packed full of people mesmerised by original contributions from a totally different perspective.

One academic in stigma was overheard to say to a person with dementia: “You don’t look like a person with dementia.”

That person commented that the academic didn’t, either.

Dementia Alliance International is a non-profit group of people with dementia from the USA, Canada, Australia and other countries that seek to represent, support, and educate others living with the disease, and an organisaton that will provide a unified voice of strength, advocacy and support in the fight for individual autonomy and improved quality of life.

Membership in Dementia Alliance International is free and open to people with dementia only, in any country.

Membership is open to any person with dementia who would like to be part of a global community of others with dementia where members support and encourage each other to live well with dementia, or oin others in fighting against the stigma, isolation and discrimination of dementia.

In addition to the larger countries, there has been interest from Taipei, New Zealand, St Maartens, Spain, Puerto Rico, and Japan, to name but a few. Of course, such an initiative is immediately attractive to a lot of other people who have the cash, including world philanthropists who have some personal connection with dementia.

This group has even been ‘noticed’ by the larger corporates and corporate-like entities in dementia, but people close to this group report that they are desperate to keep their autonomy and identity, despite possible (legal) enticements.

They know that they are on the threshold of massively disrupting current policy. They know they won’t be one or two bums occupying seats on research panels of large charities any more, only.

They will be there now leading the pack.

1. ADI staff get recognition for their work.

2. Final panel on Sunday includes person with dementia from USA, Scott Russell.

3. Final Panel with Scott Russell.

4. Person with dementia from Puerto Rico, Julio, speaks out as keynote. He got the only standing ovation of the morning’s speakers.

6. Kate Swaffer, from DAI, before her presentation of her model, “Prescribed disengagement”

Living longer, living better? Lessons from the Australian jurisdiction for dementia policy.

In a missive from the Australian Government, Department of Health, it is stated that,

“Dementia is predicted to become the leading cause of disability in Australia by 2016. For these reasons, the Government will take a proposal to the next meeting of Commonwealth, State and Territory Health Ministers that dementia be added to the existing list of eight National Health Priorities.”

Indeed, their Government is introducing a new Dementia Supplement to provide additional financial assistance for dementia care in recognition of the additional costs involved. There will be a significant increase in the number of people eligible for additional assistance as a result of this measure.

This year, at the #ADI2104 conference currently being held in San Juan, Puerto Rico, Noriyo Washizu from the Alzheimer’s Association Japan described how people with dementia can need support and “care in all areas of life 24/7. To achieve Living well with dementia, both of the social resources to meet the special needs of PWDs and their families and case managements ability to utilize them with a sense of ethics are crucial. Along with the development of an aging society, case management in dementia is required to focus more on the whole community and to be more integrated.”

Considering dementia as a form of disability is an important policy issue. In the English jurisdiction, a disability has to be sustained for a certain arbitrary period of time to satisfy the case law. For a chronic progressive irreversible dementia, i.e. the vast majority of dementias such as Alzheimer’s disease, this is likely to be the case. This therefore throws the legal onus onto one of equality, as disability is a protected characteristic, and away from the more gimmicky offerings popular in the English jurisdiction which in reality offer no additional financial support for people with dementia or their carers.

Kate Swaffer, affiliated in this context to the University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia, had a chance to present her ‘prescribed disengagement’ thesis on September 3 May 2014.

Kate described in November 2012 the following:

“Following diagnosis, my specialists all told me ‘to give up work, give up study, and go home for the time I had left’! I quickly termed this prescribed disengagement, and thankfully I eventually chose to ignore it. Why is it that one day I was studying a double degree, working full time, volunteering, raising a family and running a household with my husband, and the next day, told to give up work, and give up life as I knew it, and start ‘living’? This prescribed dis-engagement sets up a chain reaction of defeat and fear, which negatively impacts a person’s ability to be positive, resilient and proactive.“

She yesterday then described two models of care, one experience supporting continuing engagement, including employment for people with younger onset dementia; the medical model of Prescribed Disengagement versus the disAbility model of Continuing Engagement used in universities.

Following a diagnosis of younger onset dementia, Kate was advised to give up work, give up tertiary studies, and go home to live for the time she had left. It was at this time she termed this Prescribed Disengagement.

Kate writes in her abstract,

“The medical model of care prescribed disengaging from my pre-diagnosis life, which supports and exacerbates social inequality, stigma, isolation and discrimination. If I had been advised to use the disability model of care beyond my university campus, I would have been able to remain in paid employment, and if the symptoms of dementia were seen as disabilities, my employer would have been legally obliged to support continuing employment.”

This is significant from a policy perspective. If there were a system of ‘care coordinators’, perhaps who had especial expertise in advocacy for issues concerning the dementias, it might be that such coordinators could lobby local authorities for financial support so that they could meet their legal obligations in making ‘reasonable adjustments’ for people with dementia. This should not be something that people with dementia should be expected to ‘fight for’. It should be an essential aspect of dementia care and support provision.

Kate also briefly discussed a volunteering project in Adelaide South Australia which supports “the disability model of care.”

Kate writes,

“Treating the symptoms of dementia as disabilities rather than managing them in ways that restrict are vital to well-being, quality of life and motivation. The significant and positive social and financial impact on the person with dementia, their families, and society of being able to stay meaningfully engaged, as well as choosing to remain employed, and its impact on a person’s quality of life, is the final topic of this presentation. ”

And this, ladies and gentlemen, is what I believe policy should be heading to.

Not ‘counting the cost’ of people with dementia, framing the article as a financial burden we should all resent paying for, but valuing the contribution of people with dementia and close caregivers for what they can bring to society in a whole manner of ways.

And of course people with dementia need to be recognised as individuals, with diversity. The massive problem with the term ‘dementia friendly’ is that it encourages a notion of dementia as a homogeneous mass with all one big diagnosis, label and severity, and encourages a ‘them against us’ approach. Being inclusive and integrated are not necessarily the same.

Really proud of my friends living well with dementia at #ADI2014 Puerto Rico

29th International Conference of Alzheimer’s Disease International

Dementia: Working Together for a Global Solution

1-4 May 2014, San Juan, Puerto Rico

ADI and Asociacion de Alzheimer y Desordenes Relacionados de Puerto Rico invite representatives from around the world, from medical professionals and researchers to people with dementia and carers, all with a common interest in dementia.

The conference programme – details given on this website – has streams including research, advocacy and care.

I am particularly proud of my close friend, Kate Swaffer (@KateSwaffer).

Kate is in a volunteer advocacy position, also working as a consumer on the National Advisory Consumers Committee, and the Consumer’s Dementia Research Network.

She contributes so much value to the people who are lucky to know her.

Kate lives in Adelaide, Australia. She loves cats like me. She has a formidable interest and experience in many things such as academia, media, clinical quality, and cuisine. She happens to live with first-hand experience of living with a dementia, and is a sheer joy to learn off.

Dementia Alliance International is a non-profit group of people with dementia from the USA, Canada, Australia and other countries that seek to represent, support, and educate others living with the disease, and an organization that will provide a unified voice of strength, advocacy and support in the fight for individual autonomy and improved quality of life.

Their membership is open to anyone with any type of dementia. Click here to inquire about membership.

PHOTOS ALL BY KATE SWAFFER APART FROM THE ONES WITH KATE IN THEM

Kate sporting a very important message for those of us who are passionate about a person-centred approach promoting living well with dementia.

This philosophy does not give undue priority to a medical model which pushes drugs which currently have very modest effects, or certain vested interests.

Living well with dementia in the English jurisdiction is a policy plank I’ve extensively reviewed for the English jurisdiction here.

A wonderful picture of Kate and Gill (@WhoseShoes). I am very proud of them having made this global journey to Puerto Rico.

Kate Swaffer’s “Prescribed Disengagement”, “the sick role” and living with dementia

“Re-investing in life after a diagnosis of dementia” was a blogpost written by Kate Swaffer on January 20th 2014.

Kate’s experiences are fairly typical unfortunately.

“Following a diagnosis of dementia, most people are told to go home, give up work, in my case, give up study, and put all the planning in place for their demise such as their wills.”

“Their families and partners are also told they will have to give up work soon to become full time ’carers’. Considering residential care facilities is also suggested.”

“All of this advice is well-meaning, but based on a lack of education, and myths about how people can live with dementia. This sets us all up to live a life without hope or any sense of a future, and destroys our sense of future well being; it can mean even the person with dementia behaves like a victim, and many times their care partner as a martyr.”

Kate Swaffer has termed this “Prescribed Disengagement”, and it is clear to Kate from the huge numbers of people with dementia who are standing up and speaking out as advocates that there is still a good life to live even after a diagnosis of dementia.

Kate, who herself is a person living actively with a dementia, has suggested quite, at first sight, startling advice.

She advises everyone, “who has been diagnosed with dementia and who has done what the doctors have prescribed, is to ignore their advice, and re-invest in life.”

“I’m not talking about money, but about living well and continuing to live you pre-diagnosis life for as long as possible. Sure, get your wills and other end of life issues sorted out because dementia is a terminal illness, but there is no need not to fight to slow down the deterioration.”

“Alzheimer’s Disease International have a Charter that says “I can live well with dementia”, and this is not a joke, it can be done. They are serious about, and I am serious about it.”

And this advice from a person with dementia poses severe difficulties for the traditional narrative of dementia, needing medicalisation as a long-term condition.

In the 1950s, a founding father of medical sociology, Talcott Parsons, described illness as deviance -as health is generally necessary for a functional society – which thrust the ill person into the sick role (Parsons, T. The Social System. 1951. Glencoe, IL: The Free Press).

This role afforded the afflicted certain rights, but also certain obligations, which were described by Parsons in his four famous postulates:

- The person is not responsible for assuming the sick role.

- The sick person is exempted from carrying out some or all of normal social duties (e.g. work, family).

- The sick person must try and get well – the sick role is only a temporary phase.

- In order to get well, the sick person needs to seek and submit to appropriate medical care.

It is worrying that people with dementia should be forced to adopt an ‘out of sight out of mind’ position in society. This may be a reaction to the stigma and discrimination that people with dementia can experience.

These postulates, and societal attitudes towards illness, were vividly captured in the films such as Doctor in the House and Carry on Doctor.

The patient, in gown or pyjamas (thereby identifying and labelling them as ill), listened anxiously to the dispassionate words of the august surgeon who kindly attended their bedside, desperate for any clue as to when he or she might be released from hospital back into ‘normal’ society.

Dr Kate Granger (@KateGranger) recently described the powerful effect of pyjamas here.

I think all drs should be made to lie in a hospital bed wearing PJs & be stood over. See what it feels like. #vulnerability #powerbalance

— Kate Granger (@GrangerKate) February 26, 2014

Dementia is not on the whole ’caused’ by a ‘bad lifestyle’ – many individuals with dementia have had a strong genetic component of sorts. However, changes in the environment can be helpful for a long term condition such as dementia.

Marked environmental change for a person with dementia can of course be extremely unsettling, causing both physical and mental distress. However, appropriate signage in the environments, attractive design of homes and wards, and supportive built environments, can all, for example, improve wellbeing in dementia.

The medical profession has accordingly had to adapt to the demise of the traditional sick role. We no longer expect the subservient patient to submit to our bedside capture.

Subjecting persons with dementia to a whole variety of drugs that do not work that well for many, such as potentially anti-depressants, anti-psychotics or anti-memory loss is a subtle attempt at medicalisation capture, but is indeed living on borrowed time as other professions take over where the medics have failed.

Whole person or integrated care will do a lot here to help.

Assistive technology and internet technologies can in combination encourage independence as well as participation with wider social networks, but criticially may now bee at the convenience of persons in coming with health and illness services, rather than the convenience of the service.

Kate Swaffer advises other people with dementia that they should consider empowerment perhaps through groups who genuinely care.

I’m of course proud that the Scottish Dementia Working Group is serious about it. The European Dementia Working Group is serious about it. The Alzheimer’s Australia Dementia Advisory Committee is also serious about.

People with dementia make up the membership of these groups. And please don’t forget the Dementia Alliance International group, plus Kate’s page here which also highlights how to help with their important fundraising initiatives at a practical level.