Home » Posts tagged 'fragmentation'

Tag Archives: fragmentation

A lot more unites us in English dementia policy than divides us, potentially

It’s sometimes hard to see the big picture in the policy of England regarding dementia.

I don’t mean this in terms of the three key policy strands of the strategy, which is currently the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge. This extra layer was added onto the English dementia strategy, “Living well with dementia”, from 2009-2014.

There will be a renewal of this strategy next year. We currently don’t know what Government will be in office and power in 2015. But I am hoping the overall direction of travel will be a positive one. I would say that, wouldn’t I?

There are 3 dementia challenge champion groups, each focusing on 1 of the main areas for action: driving improvements in health and care, creating dementia friendly communities and improving dementia research.

But it is in my political philosophy to encourage a pro-social approach, not a fragmented one.

I’d like to see people working together. This can all too easily be forgotten in competitive tendering for contracts.

And things can be just as competitive in the third sector as for corporates.

This is the clinical lead for dementia in England, Prof Alistair Burns, who has oversight over all these complicated issues.

But we need to have a strong focus for the public good, especially as regards looking after the interests of people living with dementia, and their closest including all caregivers. State-third sector initiatives can work brilliantly for particular outcomes, such as encouraging greater sharing of basic information about dementia, but all concerned will hopefully feel that the people whose interests we want to protect the most benefit from a plural space with many stakeholders.

There is definitely a huge amount which has been achieved in the last few years. I do definitely agree with Sally Greengross, Chair of the All Party Parliamentary Group for dementia, that we should really take stock of what has worked and what hasn’t worked so well in the last five years, in our wish to move forward.

I say this, as it has come to my attention while reviewing the current state-of-play in policy and in research that there are potentially problematic faultlines.

1. One is diagnosis.

On the one hand, some people feel that we are under diagnosing dementia, and that there are people languishing in England waiting for a diagnosis for weeks or months.

Chris Roberts, himself living with a dementia, and a greater advocate for people living with dementia, often warns that it is essential that, despite the wait, that the diagnosis is correct.

I know of someone else in the USA who has battled on for years while waiting for a diagnosis of dementia, despite having symptoms of dementia.

On the other hand, there are concerns, particularly if teams in primary care are financially incentivised for doing so, that there might be a plethora of over diagnosed cases.

The concern here is that there might be alternative interests for why such people might be diagnosed, such as being recipients of compounds from drug companies which attach to proteins in the brain, and which might be useful in diagnosing dementia.

Or we are building a ‘new model army’ of people who are ageing, but being shoehorned into the illness model because of their memory problems?

2. Another is potential ‘competition’ between dementia charities.

Essentially, all dementia charities in England want the same thing, and will need to attract an audience through various ‘unique selling points’ through that awful marketing terminology.

But in the next few years we may see commissioning arrangements change where the NHS may involve the third sector doing different complementary rôles, such as advising and providing specialist nursing, in the same contractual arrangement.

The law might force people to work together here.

3. Another is the ‘cure versus care’ schism.

This debate has accelerated in the last few years, with the perception – rightly or wrongly – that cure – in other words the drive to find a magic bullet for dementia – is vying for attention with care. This narrative has a complicated history in fact, in parallel with moves in the US which likewise have overall seen a trend towards some people wishing for a ‘smaller state’.

But claims about finding a cure for dementias have to be realistic, and, while comparisons can be made with HIV and cancer about the impact of a cure has for absolving stigma potentially, such a debate has been done incredibly carefully.

For example, attention for cures and collaboration between Pharma and ‘better regulation’ constitute a diversion of resources away from care, potentially. In the NHS strategy for England, with social care on its knees, a drive towards personalised medicine on the back of advances from the Human Genome Project can end up looking vulgar.

I’ve also seen with my own eyes how the ‘cure vs care’ schism has seen different emphases amongst different domestic and international dementia conferences, with some patently putting people with dementia in the driving seat, and some less so (arguably).

4. Another is the exact emphasis of ‘dementia friendly communities’.

It is impossible to object to the concept of inclusivity and accessibility of communities, with recognition of the needs of people living with the various dementias.

But the term itself is possibly not quite right; as Kate Swaffer says, a leading international advocate on dementia, you would never dream of ‘black friendly communities’ or ‘gay friendly communities’ as a term.

Another issue is what the precise emphasis of dementia friendly communities is: whether it is an ideological ‘nudge’ for companies and corporates to enable competitive advantage, or whether it is driven by a more universal need to enshrine human rights and equality law.

As Toby Williamson from the Mental Health Foundation mooted, the need for an employer to make reasonable adjustments for cognitive disAbility is conceptually and legally is actually the same as the need for an employer to build an access ramp for a person who is in a wheelchair and physically disabled?

There can also be a problem in who wishes to be “the dominant stakeholder”. Is it the person with dementia? Or unpaid caregiver? Or paid carer? Or professional such as CPN, physio, OT, speech and language therapist, neurologist, physician or psychiatrist? Is it a dementia adviser or specialist nurse?

If we are to learn the lessons from the Carers’ Trust/RCN “Triangle of Care”, it is essential to learn from all stakeholders in the articulation of a personalised care and support plan? I feel this is important in whole person care if we are to have such plans in place, which recognise professional pro-active clinical help, in trying to assist in avoidable admissions to hospital.

But here we have to be extremely careful. An admission to hospital or appearance at A&E should not always be sign of ‘failure’ of care in the community.

5. Yet another source of division is that we all do our own things.

This is problematic, if we do our own things. We end up being secretive about which people we’re talking to. Or which conferences we’re going to.

Or if countries don’t talk to each other, even if they have similar aims in diagnosis, and post-diagnostic care and support (including the global dementia friendly communities policy). Or if we don’t share lessons learnt (such as, possibly, the beneficial impact of treating high blood pressure on dementia prevalence in one country).

Or if certain people become figureheads in dementia. But no man is an island.

I still feel that there’s a lot more that unites us than divides us.

Anyway, I’ll leave it to people on the frontline, and in communities, much more able than me, to work out what they want.

Keogh: Is the solution to failed outsourcing more failed outsourcing?

Sir Bruce Keogh has published a report on the first stage of his review of urgent and emergency care in England. You can read more about the review as it progresses on NHS Choices.

There are various potential causes of the current A&E problems. One reason might be that many people anecdotally seem to have trouble in getting a ‘routine’ GP appointment.

Labour says the crisis has been made worse by job cuts under this Government — such as the loss of 6,000 nursing posts since the election, and decisions to axe NHS Direct and close walk-in centres.

Sir Bruce says the current system is under “intense, growing and unsustainable pressure”. This is driven by rising demand from a population that is getting older, a confusing and inconsistent array of services outside hospital, and high public trust in the A&E brand.

Invariably, the response, from either those of are of a political inclination, or uneducated about macroeconomics, or both, is that “we cannot afford it”. This is dressed up as “sustainability”, but the actual macroeconomic definition of sustainability is being bastardised for that purpose.

Unite, which has 100,000 members in the health service, said this year that it wanted the “Pay Review Body” to “grasp the nettle” of declining living standards of NHS staff. “The idea behind the flat rate increase is that the rise in the price of a loaf of bread is the same whether you are a trust chief executive or a cleaner. Why should the CEO get a pay increase of more than ten times that of the cleaner, as would be the case if you have a percentage increase,” said Unite head of health Rachael Maskell.

According to one recent report, the boss of a failing NHS trust was awarded a £30,000 pay rise as patients were deprived of fluids and forced to wait in a car park because A&E was full. Karen Jackson, chief executive of Northern Lincolnshire and Goole Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, is reported to have accepted a 20% increase last year, taking her salary from £140,000 to £170,000.

Even if you refute that the global financial crash was due to failure of the investment banking sector, it’s impossible to deny that the current economic recovery is not being ‘felt’ by many. Indeed, some City law firms have unashamedly reported record revenues in recent years. Many well-known multi-national companies have yet further managed to avoid paying corporation tax in this jurisdiction.

Sir Bruce Keogh has himself admitted that extra money and “outsourcing” of some services to the private sector will be used to attempt to head off an immediate crisis, but will say the whole system of health care needs to be redesigned to meet growing long-term pressures.

This is on top of an estimated £3bn reorganisation of the NHS which the current Government has denied is ‘top down'; in their words, it is a ‘devolving’ reorganisation; similar to how the ‘bedroom tax’ should be a ‘spare room subsidy’ according to the Government and the BBC.

A poet who uses language far better than either the current Coalition or the BBC is Samuel Taylor-Coleridge. One of his poems, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”, relates the experiences of a sailor who has returned from a long sea voyage.

The poet uses narrative techniques such as repetition to create a sense of danger, the supernatural, or serenity, depending on the mood in different parts of the poem.

Water, water, every where,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, every where,

Nor any drop to drink.

Like the manner of this poem, the mood of the NHS changes with the repetition of certain language triggers such as ‘sustainability’.

More than £4bn of taxpayer funds was paid out last year to four of Britain’s largest outsourcing contractors – Serco, Capita, Atos and G4s – prompting concerns that controversial firms have become too big to fail, according to the National Audit Office.

But according to the National Audit Office, increasingly powerful outsourcing companies should be forced to open their books on taxpayer-funded contracts, and be subject to fines and bans from future contracts in the event that they are found to have fallen short. The report estimates that the four groups together made worldwide profits of £1.05bn, but paid between £75m and £81m in UK corporation tax. Atos and G4S are thought to have paid no tax at all.

“[This report] raises some big concerns: the quasi-monopolies that have sprung up in some parts of the public sector; the lack of transparency over profits, performance and tax paid; the inhibiting of whistleblowers; the length of contracts that taxpayers are being tied into; and the number of contracts that are not subject to proper competition,” said Margaret Hodge, chair of the public accounts committee, who commissioned the NAO to carry out the study.

As for the NHS, Keogh describes it as ‘complete nonsense’ that his proposals are a ‘downgrading’ or ‘two tier system’. As an example, Keogh says there has been 20% increased survival rate in major trauma by treatment in a specialist treatment on the basis of his 25 designated trauma centres. Keogh’s focus is on major trauma, stroke or heart attack.

This is a perfectly reasonable observation, in the same way that the existence of the tertiary referral medicine centres for clinical medicine, such as the Brompton, the Royal Marsden or Queen Square, for highly specialist medical management of respiratory, palliative and neurological medicine should not be interpreted as the NHS Foundation Trust ‘tier’ offering a second-rate service on rare conditions. Developed after an extensive engagement exercise, the new report proposes a new blueprint for local services across the country that aims to make care more responsive and personal for patients, as well as deliver even better clinical outcomes and enhanced safety.

Keogh advocates a system-wide transformation over the next three to five years, saying this is “the only way to create a sustainable solution and ensure future generations can have peace of mind that, when the unexpected happens, the NHS will still provide a rapid, high quality and responsive service free at the point of need.”

But it is highly significant that this ‘beefed up system’ is building on the rocky foundation for the NHS since May 2010, where the Coalition has ‘liberalised the market’. Far from giving the NHS certainty, the Health and Social Care Act (2012), as had been widely anticipated, has liberated anarchy and chaos.

There are many more private providers delivering profit for their shareholders.

However, the National Health Service has been propelled at high speed into a fragmented, disjointed service with numerous providers not sharing critical information with each other let alone the public.

Only this week, Grahame Morris, Labour MP for Easington, warned yet again about how private providers are able to hide behind the ‘commercial sensitivity’ corporate veil when it comes to freedom of information act requests. This wouldn’t be so significant if it were not for the fact that ‘beefing up’ the NHS 111 system is such a big part of Keogh’s plan.

NHS 111 was launched in a limited number of regions in March 2013 ahead of a planned national launch in April 2013. This initial launch was widely reported to be a failure. Prior to the launch the British Medical Association – affectionately referred to by the BBC as “The Doctors’ Union” – had sufficient concern to write to the Secretary of State for Health requesting that the launch be postponed. On its introduction, the service was unable to cope with demand; technical failures and inadequate staffing levels led to severe delays in response (up to 5 hours), resulting in high levels of use of alternative services such as ambulances and emergency departments. The public sector trade union UNISON had also recommended delaying the full launch.

The service has run by different organisations in different parts of the country, with private companies, local ambulance services and NHS Direct, which used to operate the national non-emergency phone line, all taking on contracts last year. The problems led to the planned launch date being abandoned in South West England, London and Midlands (England). In Worcestershire, the service was suspended one month after its launch in order to prevent patient safety being compromised. The 111 non-emergency service has faced criticism since a trial was launched in parts of England last month. Some callers said they had struggled to get through or left on hold for hours.

Andy Burnham, Labour’s shadow health secretary, at the time accused the Government of destroying NHS Direct, “a trusted, national service” in an “act of vandalism”. “It has been broken up into 46 cut-price contracts,” he said. “Computers have replaced nurses and too often the computer says ‘go to A&E’.”

Clare Gerada, also at the time, said that the introduction of 111 had “destabilised” a system that was functioning well under NHS Direct and called for non-emergency phone services to be operated in closer collaboration with local GP services.

“The big problem about 111 is of course money,” she said. “It was the lowest bidders on the whole that won the contracts… If you pay £7 a call versus £20 a call you don’t have to be an economist to see that something’s going to be sacrificed. What’s sacrificed is clinical acumen.”

Keogh is keen to put a different gloss on the situation now. He admits that people wish to talk to clinician if they are worried, rather than an “unqualified call handler”. He says that this is possible ‘but we need to put the infomatics in place’. 40% of patients need reassurance, according to Keogh. Keogh then argues that, if there is a concern, an ambulance can be called up, or a GP appointment can be arranged.

However, for this system to work, people offering out-of-hours services will not just be dealing with a third degree burn in the absence of any previous medical history at all. There will be patients with long-term conditions like diabetes, asthma and chronic heart disease, who might not have to use A&E services so frequently if they were supported to manage their health more effectively.

Some of these patients will be ‘fat filers’, where it’s impossible to know what a medical presentation might be without access to complex medical notes; e.g. a cold in a profoundly immunosuppressed individual is an altogether different affair to a cold in a healthy individual. Likewise, individuals with specific social care needs will need to be recognised in any out-of-hours service.

The aim of ‘beefing up’, as Keogh puts it, the ‘National Health Service’ was to make it a coherent service across all disciplines, with clinicians – as well as top CEOs – adequately resourced out of general taxation.

As it is, it is pouring more money into people who have not delivered the goods thus far.

The solution to failed outsourcing cannot be more failed outsourcing. As one interesting article in ‘Computer Weekly’ explained recently, the “NHS 111 chaos is a warning to organisations outsourcing”.

The report has also made a case for improved training and investment in community and ambulance services, so that paramedics provide more help at the scene of an incident, with nurses and care workers dispatched to offer support in the home, so fewer patients are taken to hospital. This can work extremely well, provided that resources are allocated to such services first, and there is a proven improvement in quality (which seems very likely.)

And if somebody tells you it’s all about sustainability – tell them there’s water water everywhere, and there’s not a drop to drink as this recent event provoked.

What’s best for a person isn’t necessarily what’s best for a hospital

It is pretty clear that the NHS as currently engineered puts Foundation Trusts on an elevated platform. Hospitals, being paid on the basis of activity involved for any one patient, can act for a sink for funding, when the health of any particular person is not easily matched to the aggregate level of activity for that person in a hospital.

The problem with ‘money following the patient‘ is it depends on whether you view it to be a success or failure that more money is spent on you the more ill you become. When a patient is admitted for an acute medical emergency in England, the care pathway can be pretty unambiguous. Most reasonable doctors on hearing about a history of cough, sputum and temperature, for a person with new breathing difficulties, on seeing the appropriate chest x-ray, would embark on a management of pneumonia; depending on the hospital, the course of antibiotics would be pretty standard from i.v. to oral, and the person would end up being discharged.

However, ‘activity based costing‘ and ‘payment by results‘ for hospital totally ignore the health of a person outside hospital. And if a healthcare model is to shift with time to ‘whole person care‘, what happens to a person outside of hospital is going to become increasingly important. If a person is better ‘controlled‘ for diabetes in the community, it is hoped that emergency admissions, such as for the diabetic ketocacidotic coma, can be avoided; or for example if a person is able to monitor their breathing peak flow in the community and notice the warning signs (such as a change in the colour of sputum), an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease may be headed off at the pass.

Medicine is not an exact art or science, and the approach of ‘payment-by-results’, of a managerial accounting approach of activity-based costing, is at total odds to how decisions are actually made. Even in complex economics, within the last decade or so, the idea of “bounded rationality” has conceded that in decision-making, rationality of individuals is limited by the information they have, the cognitive limitations of their minds, and the finite amount of time they have to make a decision. Many ‘decision makers’ are not in fact perfectly rational, and it is likely that even the best doctors will differ in exact details for management of a patient in hospital for any given set of circumstances.

In health care, value is defined as the patient health outcomes achieved per pound spent. Value should be the pre-eminent goal in the health care system, because it is what ultimately matters for patients. Value encompasses many of the other goals already embraced in health care, such as quality, safety, patient centeredness, and cost containment, and integrates them.

However, despite the overarching significance of value in health care, it has not been the central focus.

The failures to adopt value as the central goal in health care and to measure value are arguably the most serious failures of the medical community.

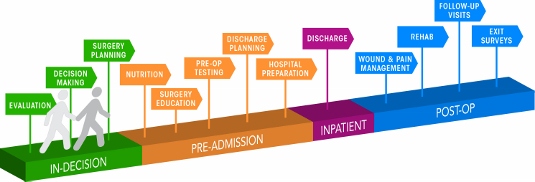

Health care delivery involves numerous organisational units, ranging from hospitals, to departments and divisions, to physicians’ practices, to units providing single services. The fundamental failing has been not to acknowledge how all these units interact in the “patient journey”.

In health care, needs for specialty care are determined by the patient’s medical condition. A medical condition is an interrelated set of patient medical circumstances — such as breast cancer, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, asthma, or congestive heart failure — that is best addressed in an integrated way. Therefore, a patient can be ‘plugged into the system’, as Mr X attending the specialist cystic fibrosis clinic at a local hospital. However, it is equally true to say that there are many patients with many different conditions, which interact either in disease process or treatment. And there are people who may later develop a medical illness who are perfectly well at any one ti,e.

For primary and preventive care, value could be measured for defined patient groups with similar needs. Patient populations requiring different bundles of primary and preventive care services might include, for example, healthy children, healthy adults, patients with a single chronic disease, frail elderly people, and patients with multiple chronic conditions. Each patient group has unique needs and requires inherently different primary care services which are best delivered by different teams, and potentially in different settings and facilities. However, life is clearly not so simple, and the beauty about the National Health Service is that it does not consider a person as the sum of his individual insurance packages.

Care for a medical condition (or a patient population) usually involves multiple specialties and numerous interventions. The most important thing here is that value for the patient is created not by any one particular intervention or specialty, but by the combined efforts of all of them. (he specialties involved in care for a medical condition may vary among patient populations. Rather than “focused factories” concentrating on narrow sets of interventions, we need integrated practice units accountable for the total care for a medical condition and its complications. To give as an example, optimal glucose control for diabetes in the community could possibly mean fewer referrals to the specialist eye clinic for the condition of diabetic retinopathy, an eye manifestation of diabetes, or to the vascular surgeon for a gangrenous toe requiring amputation.

A major barrier to delivering this care will be a fragmented, outsourced or privatised, NHS. In care for a medical condition, then, value for the patient is created by providers’ combined efforts over the full cycle of care — not at any one point in time or in a short episode of care. The only way to accurately measure value, then, is to track individual patient outcomes and costs longitudinally over the full care cycle. And this will be difficult the more care providers there are for any one patient.

Although outcomes and costs should be measured for the care of each medical condition or primary care patient population, current organisational structure and information systems make it challenging to measure (and deliver) value. Thus, most providers fail to do so. Providers tend to measure only the portion of an intervention or care cycle that they directly control or what is easily measured, rather than what matters for outcomes. For example, current measures often cover a single department (too narrow to be relevant to patients) or outcomes for a hospital as a whole, such as infection rates (too broad to be relevant to patients). Or providers measure what is billed, even though current reimbursement is for individual services or short episodes.

A way to get round this problem is to consider “indicators” which are are biological measures in patients that are predictors of outcomes, such as glycated hemoglobin levels (“HBA1c”) measuring blood-sugar control in patients with diabetes. Indicators can be highly correlated with actual outcomes over time, such as the incidence of acute episodes and complications. A HbA1c can be a good indicator of the compliance of an individual with diabetes with his or her medication or diet.

Indicators also have the advantage of being measurable earlier and potentially more easily than actual outcomes, which may be revealed only over time.

This is where over-focus on the wrong measure can be unhelpful. The launch of the ‘friends and family test’, which has seen an explosion of innovative technologies being sold to NHS Foundation Trusts over all the land, may be an important means of ensuring patient safety. Or it may not. We don’t know, as the data on this doesn’t exist.

However, patient satisfaction has multiple meanings in value measurement, with greatly different significance for value. It can refer to satisfaction with care processes. This is the focus of most patient surveys, which cover hospitality, amenities, friendliness, and other aspects of the service experience. Though the service experience can be important to good outcomes, it is not itself a health outcome. The risk of such an approach is that focusing measurement solely on friendliness, convenience, and amenities, rather than outcomes, can distract providers and patients from value improvement.

Value measurement in health care today in the English NHS is rather limited, and highly imperfect. Most physicians lack critical information such as their own rates of hospital readmissions, or data on when their patients returned to work. Not only is outcome data lacking, but understanding of the true costs of care is virtually absent. Most physicians do not know the full costs of caring for their patients — the information needed for real efficiency improvement.

In the recent target-driven culture of the English NHS, senior physicians are well aware of how length-of-stay has been gamed so there has been a ‘quick in and quick out’ mentality, seeing readmission rates for certain patients with cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease sky-high.

At worst, what could have been a properly managed non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome ultimately ends up being a full-blown heart attack. Or what could have been a minor transient ischaemic attack ends up being a full-blown haemorrhagic stroke, causing a patient to be in a wheelchair and numerous healthcare teams looking after him or her.

Today, measurement focuses overwhelmingly on care processes. Processes are sometimes confused or confounded not only with outcomes, but with structural measures as well. Radiologists focus on the accuracy of reading a scan, for example, rather than whether the scan contributed to better outcomes or efficiency in subsequent care. Cancer specialists are trained to focus solely on survival rates, overlooking crucial functional measures in which major improvements vital to the patient are possible.

Cost is among the most pressing issues in health care, and serious efforts to control costs have been under way for decades. At one level, there are endless cost data at all levels of the system. However, as an ongoing project with Robert Kaplan makes clear, we actually know very little about cost from the perspective of examining the value delivered for patients.

Understanding of cost in health care delivery suffers from two major problems. The first is a cost-aggregation problem. Today, health care organisations measure and accumulate costs for departments, physician specialties, discrete service areas, and line items (e.g. supplies or drugs). As with outcome measurement, this practice reflects the way that care delivery is currently organised and billed for. Today each unit or department is typically seen as a separate revenue or cost centre. Proper cost measurement is challenging because of the fragmentation of entities involved in care.

To understand costs properly, they must be aggregated around the patient rather than for discrete services, just as is the case with outcomes. It is the total costs of providing care for the patient’s medical condition (or bundle of primary and preventive care services), not the cost of any individual service or intervention, that matters for value. If all the costs involved in a patient’s care for a medical condition — inpatient, outpatient, rehabilitation, physiotherapy, dietician, occupational therapy, diagnostic services, pharmacy, physician services, equipment, facilities — are brought together, it is then finally possible to compare the costs with the outcomes achieved.

Proper cost aggregation around the patient will allow us to distinguish charges and costs, understand the components of cost, and reveal the sources of cost differences.

Today, most physicians and provider organisations do not even know the total cost of caring for a particular patient or group of patients over the full cycle of care. There has been no reason to know, and Doctors resent turning their profession of medicine into one of bean-counting.

In aggregating costs around patients and medical conditions, we quickly arrive at the second problem: “the cost-allocation problem“. Many, even most, of the costs of health care delivery are shared costs, involving shared resources such as physicians, staff, facilities, equipment, and overhead functions involved in care for multiple patients. Even costs that are directly attributable to a patient, such as drugs or supplies, often involve shared resources, such as units involved in inventory management, handling, and set-up (e.g., the pharmacy). Today, these costs are normally calculated as the average cost over all patients for an intervention or department, such as an hourly charge for the operating room. However, individual patients with different conditions and circumstances can utilize the capacity of such shared resources quite differently.

The NHS in England has latterly become obsessed by its “funding gap”. Much health care is delivered in over-resourced facilities. Routine care, for example, is delivered in expensive hospital settings. Expensive space and equipment is underutilised, because facilities are often idle and much equipment is present but rarely used. Skilled physicians and staff spend much of their time on activities that do not make good use of their expertise and training. It is not uncommon for junior doctors to end up spending hours in a hospital taking blood, putting in catheters, or putting in venflons.

It is likely that ‘payment-by-results’ will at some stage have to go. Reimbursement should cover a period that matches the care cycle. For chronic conditions, bundled payments should cover total care for extended periods of a year or more. Aligning reimbursement with value in this way rewards providers for efficiency in achieving good outcomes while creating accountability for substandard care.

Improvements in outcomes and cost measurement will greatly ease the shift to bundled reimbursement and produce a major benefit in terms of value improvement. Current organisational structures, practice standards, and reimbursement create obstacles to value measurement, but there are promising efforts under way to overcome them.

The “payment-by-results” model is a complete anethema to how decisions are made in the real world. Prospect theory is a behavioral economic theory that describes the way people choose between probabilistic alternatives that involve risk, where the probabilities of outcomes are known. The theory states that people make decisions based on the potential value of losses and gains rather than the final outcome, and that people evaluate these losses and gains using certain heuristics. The model is descriptive: it tries to model real-life choices, rather than optimal decisions. The theory was developed by Daniel Kahneman, a professor at Princeton University’s Department of Psychology, who won the Nobel Prize for economics in 2002.

It is a pity that the payment-by-results ideology has been so overwhelming, perhaps powerfully pushed for by the accountants and management consultants wishing to drive ‘efficiency’ in the NHS, taking the media with them on this escapade. However, it is poorly aligned to how healthcare, psychiatric care and social care professionals make decisions in the real world.

Critics will correctly argue that value is notoriously difficult to measure, and might be virtually impossible to measure across a ‘care cycle’. Indeed the original criticism of the Kaplan and Cooper (1992) account of ‘activity based costing’ warned against organisations allocating excessive resources to collecting information which they are then able to make use of properly.

We are quickly coming to an age where it is going to be a ‘good outcome’ to keep a frail patient out of hospital through high quality care in the community through integrated teams. By that stage, the ideological shift from cost to value will have needed to have taken place, and funding models will have to reflect more the drive towards value and ultimate clinical outcome.

#Lab13 Stop #NHS2?

Whilst many of us find the concept of the NHS being outsourced and privatised to the highest bidder quite revolting, there is also a vocal minority, with cumulatively sufficient numbers of them to hold office if not power, who believe that the Health and Social Care Act (2012) and concomitant “top down reorganisation” bring innovative, free market forces to make the NHS a “global brand leader” in the competitive world of healthcare. They believe it’s simply about making the new NHS, ‘NHS2′, “fit for purpose”, and it was only a matter of time under the two main parties (Labour and Conservative) that yet a further reorganisation of the NHS would become necessary. Arguably, the public would learn to love its benefits. Similarly, the public would learn to love HS2, “high speed 2″. Problematically, despite supportive noises from Osborne and Hammond about HS2, HS2 could still become derailed.

As the UK Labour Party hit their latest debacle of a Philip Morris stand at conference, having wished to make a stance on standard packaging of cigarettes, the tensions between populist stances maximising Labour’s electoral chances on May 7th 2015 and highly principled strategic stances based on policy have arguably never been stronger. If you’re not in Brighton for the Labour Party Conference, you might have caught sight of the “#stopHS2″ campaign in the social media. Also, if you have been spending time looking at tweets about Labour’s health and social care policy, you can see the criticism of Labour over the accelerated privatisation of the NHS is not without its critics. Even intelligent well-meaning Labour supporters have been collecting electronic clippings of the continued interest in the private finance initiative (and the involvement of Coopers and Lybrand in the Major and Blair governments) and the independent sector treatment centres of the Blair government. At a time when Labour is seeking to restore faith in the political process under Lord Ray Collins of Highbury, the question that Labour is so strapped of cash that it needs Philip Morris support remains an irritating one? The notion of the ‘democratic deficit’ is seen in both HS2, as such a policy issue not even mooted in the 2010 general election which seems to have gathered cross-party support (a bit like ‘personal health budgets), and in ‘NHS2′, the top-down NHS reorganisation implemented by the Conservatives with the Liberal Democrats aiding and abetting. So if nobody voted for either policy, where did the policies from? It might not be quite the “smoke-filled rooms of beer and sandwiches”, but powerful lobbying of private commercial interests are likely to have been proven influential in the past.

Whatever the official party positions on HS2 (and this has been subject to flux in recent months), both HS2 and NHS2 have formidable national grassroot campaigns in places. Stop HS2 is the national grassroots campaign against HS2, the proposed new High Speed Two railway. Theri mission is To Stop High Speed Two by persuading the Government to scrap the HS2 proposal and to facilitiate local and national campaiging against High Speed Two.Their supporters come from a wide range of backgrounds and from across the political spectrum. The “Stop Section 75 campaign” from 38 degrees aimed at thwarting the major competitive tendering construct of the Health and Social Care Act (2012), but it was ultimately unsuccessful. 38 Degrees is the one of the UK’s biggest campaigning communities, with over 1 million members. They share a desire for a “more progressive, fairer, better society”. They tried to argue earlier this year to all MPs and members of the House of Lords that our NHS is precious – and the public overall don’t want it privatised. Privatisation for both HS2 and NHS2, here, essentially means diverting of state resources into private sector hands.

Both HS2 and NHS2 are staggeringly expensive projects in this day when we keep on having austerity rammed down our throats, but admittedly the scale of spending of each project is different. Nonetheless by anyone’s standards, £32 billion as an estimate for #HS2 is an eye-watering amount of cash. It works out at well over £1,000 for every single family up and down the United Kingdom, and large numbers of us remain unconvinced that this will be money well spent. The exact cost of the NHS2 top down reorganisation is in its own different way unclear. Following on from Labour’s claims of ‘hidden costs’ last November, Shadow Health Secretary Andy Burnham claimed that the reorganisation planned in the Government’s Health and Social Care Bill (as it was then) amounted to costs of £3.5 billion, far more than the £1.2 – £1.3 billion claimed by the Government. Minister of State for Health Simon Burns branded this figure a ‘mistake’, reasserting the Government’s own figures as the correct estimate.

Also, both policies HS2 and NHS2 are “unpopular” with the general public. This is reflected by the fact they have never been openly discussed with the public before implementation. The public remain unconvinced about the actual rationale for HS2 to bring greater equity between London and regions of England (critics argue that the plan would benefit London more than the regions). Likewise, at a time when the ‘cost of living’ has been thrust into pole position by Ed Miliband, the cost of non-NHS providers providing NHS products and services for a cost which enhances shareholder dividend, the case for pimping out the NHS to the private sector has never been more badly timed. A YouGov poll into spending cuts commissioned by the TaxPayers’ Alliance last summer found that 48 per cent of people supported cancelling plans for HS2, with barely a third wanting to press ahead with the scheme. And it’s hardly surprising that the public remains so reluctant to support it. Andrew Lansley’s NHS reorganisation is unpopular both with the public and health service staff. Such a large scale reorganisation (likened to “throwing a grenade into the NHS”, by Conservative MP Dr Sarah Wollaston) would be difficult even in the Blair years of increased funding.

Research published by the TaxPayers’ Alliance last year into the hidden costs of HS2 further set alarm bells ringing, highlighting, for example, the billions of additional funding that would be necessary to mitigate the environmental effects of the line by running more of it underground or through tunnels. Andy Burnham, Shadow Health Secretary, spoke of a “bruised and battered” NHS that was in a “fragile” state. Burnham believes there is now a choice to be made about whether we want to allow the inexorable advance of competition in the market, or whether we want to hold on to a planned national system that many successive generations in England have benefited from.

Both HS2 and NHS2 pose fundamental problems for the Labour policy review, still currently underway. They poses problems for the UK economy – how much benefit are we actually going to get from this surge of spending to implement them? They also pose problems for the public’s institutions. Both the railway network and the NHS are cherished by the public but in different ways. Many citizens, whether they are Labour voters, think that the privatised railway industry has become costly, fragmented and essentially a shambles following Tory privatisation, and some would fundamentally like it in state ownership. While Burnham has consistently said the dichotomy between public and private is a false dichotomy, he has also reiterated his affirmation for the ‘NHS preferred provider’ policy which is a small attempt to mitigate against the loss of a state-run comprehensive universal National Health Service.

Both HS2 and NHS2 are ‘elephants in the room’, and it is merely a question of time for how long they may remain hidden.

The Tories have never had any ideology, so it's not surprising they've run out of steam

A lot of mileage can be made out of the ‘story’ that the Coalition has “run out of steam”, and this week two commentators, Martin Kettle and Allegra Stratton, branded the Queen’s Speech as ‘the beginning of the end’. There is a story that blank cigarette packaging and minimum alcohol pricing policies have disappeared due to corporate lobbying, and one suspects that we will never get to the truth of this. The narrative has moved onto ‘immigration’, where people are again nervous. This taps into an on-running theme of the Conservatives arguing that people are “getting something for nothing”, but the Conservatives are unable to hold a moral prerogative on this whilst multinational companies within the global race are still able to base their operations using a tax efficient (or avoiding) base. Like it or now, the Conservatives have become known for being in the pockets of the Corporates, but not in the same way that the Conservatives still argue that the Unions held ‘the country to ransom’. Except things have moved on. The modern Conservative Party is said to be more corporatilist than Margaret Thatcher had ever wanted it to be, it is alleged, and this feeds in a different problem over the State narrative. The discussion of the State is no longer about having a smaller, more cost-effective State, but a greater concern that ‘we are selling off our best China’ (as indeed the late Earl of Stockton felt about the Thatcherite policy of privatisation while that was still in its infancy). The public do not actually feel that an outsourced state is preferable to a state with shared responsibility, as the public do not feel in control of liabilities, and this is bound to have public trust in privatisation operations (for example, G4s bidding for the probation service, when operationally it underperformed during the Olympics).

It is possibly this notion of the country selling off its assets, and has been doing so under all administrations in the U.K., that is one particular chicken that is yet to come home to roost. For example, the story that the Coalition had wished to push with the pending privatisation of Royal Mail is that this industry, if loss making, would not ‘show up’ on the UK’s balance sheet. There is of course a big problem here: what if Royal Mail could actually be made to run at a profit under the right managers? Labour in its wish to become elected in 1997 lost sight of its fundamental principles. Whether it is a socialist party or not is effectively an issue which seems to be gathering no momentum, but even under the days of Nye Bevan the aspiration of Labour was to become a paper with real social democratic clout. One of the biggest successes was to engulf Britain in a sense of solidarity and shared responsibility, taking the UK away from the privatised fragmented interests of primary care prior to the introduction of the NHS. The criticism of course is that Bevan could not have predicted this ‘infinite demand’ (either in the ageing population or technological advances), but simply outsource the whole lot as has happened in the Conservative-led Health and Social Act (2012) is an expedient short-term measure which strikes at the heart of poverty of aspiration. It is a fallacy that Labour cannot be relevant to the ‘working man’ any more, as the working man now in 2013 as he did in 1946 stands to benefit from a well-run comprehensive National Health Service. Even Cameron, in introducing his great reforms of the public sector in 2010/1 argued that he thought the idea that the public sector was not ‘wealth creating’ was nonsense, which he rapidly, unfortunately forgot, in the great NHS ‘sell off’.

The Conservatives have an ideology, which is perhaps outsourcing or privatisation, but basically it comes down to making money. The fundamental error in the Conservative philosophy, if there is one, is that the sum of individual aspiration is not the same as the value of collective solidarity and sharing of resources. This strikes to the heart of having a NHS where there are winners and losers, for example where the NHS can run a £2.4 bn surplus but there are still A&E departments shutting in major cities. Or why should we tolerate a system of ‘league tables’ of schools which can all too easily become a ‘race to the bottom’? Individual freedom is as relevant to the voter of Labour as it is to the voter of the Conservative Party, but if there is one party that can uphold this it is not the Conservatives or the Liberal Democrats. No-one on the Left can quite ignore why Baroness Williams chose to ignore the medical Royal Colleges, the RCN, the BMA or the legal advice/38 degrees so adamantly, although it does not take Brains of Britain to work out why certain other Peers voted as they did over the section 75 regulations as amended. But the reason that Labour is unable to lead convincingly on these issues, despite rehearsing well-exhausted mantra such as ‘we are the party of the NHS’, is that the general public received a lot of the same medicine from them as they did from the Conservatives or the Liberal Democrats. Elements of the public feel there is not much to go further; the Labour Party will still be the party of the NHS for some (despite having implemented PFI and NHS Foundation Trusts), and the Conservatives will still be party of fiscal responsibility for some (despite having sent the economy into orbit due to incompetent measures culminating in avoidance of a triple-dip).

It doesn’t seem that Labour is particularly up for discussion about much. It gets easily rumbled on what should be straightforward arms of policy. For example, Martha Kearney should have been doing a fairly uncontroversial set-piece interview with Ed Miliband in the local elections, except Miliband came across as a startled, overcaffeinated rabbit in headlights, and refused doggedly to explain why his policy would not involve more borrowing (even when Ed Balls had said clearly it would.) Miliband is chained to his guilty pleasures of being perceived as the figurehead of a ‘tax and spend’ party, which is why you will never hear of him talking for a rise in corporation tax or taxing excessively millionaires (though he does wish to introduce the 50p rate, which Labour had not done for the majority of its actual period in government). It uses terms such as “predistribution” as a figleaf for not doing what many Labour voters would actually like him to do. Labour is going through the motions of receiving feedback on NHS policy, but the actual grassroots experience is that it is actually incredibly difficult for the Labour Party machine even to acknowledge actually well-meant contributions from specialists. The Labour Party, most worryingly, does not seem to understand its real problem for not standing up for the rights of workers. This should be at the heart of ‘collective responsibility’, and a way of making Unions relevant to both the public and private sector. Whilst it continues to ignore the rights of workers, in an employment court of law over unfair dismissal or otherwise, Labour will have no ‘unique selling proposition’ compared to any of the other parties.

Likewise, Labour, like the Liberal Democrats, seems to be utterly disingenious about what it chooses to support. While it seems to oppose Workfare, it seems perfectly happy to vote with the Government for minimal concessions. It opposes the Bedroom Tax, and says it wants to repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2012), but whether it does actually does so is far from certain; for example, Labour did not reverse marketisation in the NHS post-1997, and conversely accelerated it (admittedly not as fast as post-2012). No-one would be surprised if Ed Miliband goes into ‘copycat’ mode over immigration, and ends up supporting a referendum. This could be that Ed Miliband does not care about setting the agenda for what he wants to do, or simply has no control of it through a highly biased media against Labour.

Essentially part of the reason that the Conservatives have ‘run out of steam’ is that they’ve run out of sectors of the population to alienate (whether that includes legal aid lawyers or GPs), or run out of things to flog off to the private sector (such as Circle, Serco, or Virgin). All this puts Labour in a highly precarious position of having to decide whether it wishes to stop yet more drifting into the private sector, or having to face an unpalatable truth (perhaps) that it is financially impossible to buy back these industries into the public sector (and to make them operate at a profit). However, the status quo is a mess. The railway industry is a fragmented disaster, with inflated prices, stakeholders managing to cherrypick the products they wish to sell to maximise their profit, with no underlying national direction. That is exactly the same mess as we have for privatised electricity, or privatised telecoms. That is exactly same mess as we will have for Royal Mail and the NHS. The whole thing is a catastrophic fiasco, and no mainstream party has the bottle to say so. The Liberal Democrats were the future once, with Nick Clegg promising to undo the culture of ‘broken promises’ before he reneged on his tuition fees pledge. UKIP are the future now, as they wish to get enough votes to have a say; despite the fact they currently do not have any MPs, if they continue to get substantial airtime from all media outlets (in a way that the NHS Action Party can only dream of), the public in their wisdom might force the Conservatives or Labour to go into coalition with UKIP. There is clearly much more to politics than our membership of Europe, and, while the media fails to cover adequately the destruction of legal aid or the privatisation of the NHS, the quality of our debate about national issues will continue to be poor. Ed Miliband must now focus all of his resources into producing a sustainable plan to govern for a decade, the beginning of which will involve an element of ‘crisis management‘ for a stagnant economy at the beginning. The general public have incredibly short memories, and, although it has become very un-politically correct to say so, their short-termism and thirst for quick remedies has led to this mess. Ed Miliband seems to be capable of jumping onto bandwagons, such as over press regulation, but he needs to be cautious about the intricacies of policy, some of which does not require on a precise analysis of the nation’s finances at the time of 7th May 2015. With no end as yet in sight for Jon Cruddas’ in-depth policy review, and for nothing as yet effectively Labour to campaign on solidly, there is no danger of that.

'Work in progress' : Andy Burnham's 2012 conference speech throws up tough challenges

Andy Burnham has vowed to reverse the “rapid” privatisation of NHS hospitals in England if Labour wins power. In particular, Mr Burnham said he feared the new freedom for hospitals to earn 49% of their income from private work would “damage the character and culture” of the NHS and take it closer to an American model.

The issue of fragmentation of the NHS is a genuine problem in the NHS, as enacted this year. This is manifest in a number of different guises, such as lack of clarity as to which private entity owns what for local services, the abolition of statutory bodies involved in healthcare (such as the National Patient Safety Agency and the Health Protection Agency), and the phenomenon of “postcode lottery” in healthcare provision.

Andy Burnham clearly wishes “Labour values” of collaboration and solidarity to be pervasive in an equitable National Health Service, rather than competition, where there are winners and losers. This is particularly interesting from a business management sense, as it has long been a source of academic interest in innovation management how the “innovators’ dilemma” is solved in the private sector. This is the practical business question posed by Prof Clay Christensen, professorial fellow in innovation at Harvard, as to how it is possible, that, amongst private entities in the market place, business entities can secure competitive advantage, while working together sharing knowledge in seamless collaboration.

It seems pretty likely that, even if Labour win the 2015 general election and the Health and Social Act (2012) is repealed, commissioning will exist in some form, with Labour taking forward ‘best practice’ from the experiences of clinical commissioning groups (CCGS). There is no inkling that, whilst certain structures are in the process of being abolished for some time (such as the PCTs and SHAs), the CCGS and NHS Foundation Trusts will follow suit. Indeed, Professor Brian Edwards, special adviser to the Institute of Healthcare Managers, said he was “appalled and frustrated” at news the Francis Report would not be published until January 2013, and called it “a cruel blow” to the families of victims. This report discusses the failings at hospitals in Mid Staffordshire between 2005 and 2009, and is anticipated to be invaluable in developing further NHS foundation trusts.

Integration in person-centred care has always been a hallmark of excellent medical care, and Burnham keens to bring this out as a dominant theme in components of his new Health Bill in 2015 or 2016 if elected. When patients present to their G.P., they simply do not present as isolated medical diagnoses. For example, if an elderly patient, who may incidentally have a probable diagnosis of dementia, falls, a GP would be concerned with the patient is at risk of a fracture due to underlying osteoporosis, has poor eyesight due to a cataract for example, or leads a life in a cluttered home environment due to lack of social care. There are a plethora of problems which are likely to cause an individual to come into contact with the NHS, and the integration of health and social care is indeed entirely in keeping with Nye Bevan’s original aspiration for the NHS. The ideal would be of course to have an integrated health and social care service, but much time (and money) has been lost by the Coalition kicking the Dilnot review ‘into the long grass’ when we were already supposedly meant to be looking for greater efficiencies through the Nicholson Challenge.

Moves are clearly afoot as to who is providing the services, with various morphologies in terminology (for example “NHS preferred provider”, “any willing provider”, or “any qualified provider”). Closer to home for the current delegates in Manchester, patients will be taken to hospital by a bus company after the North West Ambulance Service (NWAS) failed to win a contract. It will not affect 999 emergency call-outs. Arriva, which run bus services throughout Greater Manchester, will replace NWAS which currently runs the service but was outbid by Arriva after the the service was put out to tender.

Chris Ham, Chief Executive of the Kings Fund, has concerns which are perfectly fair, in response:

“Andy Burnham has outlined a vision for the future of health and social care which accentuates the differences between the Labour Party and the government on the NHS. He is right to stress the need for fundamental change in health and social care services. Our own work has made the case for radical changes to ensure the NHS is fit to meet the challenges of the future as the population ages and health needs change.

This includes moving care closer to people’s homes and re-thinking the role of hospitals which must change to improve the quality of specialist services and better meet the needs of older patients. We also welcome his emphasis on delivering integrated care – the challenge now is to move integrated care from the policy arena and make it happen across the country at scale and pace.

However, while the long term vision is ambitious, the details of Labour’s plans are sketchy. A number of questions will need to be answered in the policy review announced today. For example, it is not clear how local authorities could take on the role of commissioning health care without further structural upheaval. And despite the Shadow Chancellor’s pledge earlier in the week, it is not clear how Labour would ensure adequate funding for social care.”

Text of speech given this morning in Manchester.

Conference, my thanks to everyone who has spoken so passionately today and I take note of the composite.

A year ago, I asked for your help.

To join the fight to defend the NHS – the ultimate symbol of Ed’s One Nation Britain.

You couldn’t have done more.

You helped me mount a Drop the Bill campaign that shook this Coalition to its core.

Dave’s NHS Break-Up Bill was dead in the water until Nick gave it the kiss of life.

NHS privatisation – courtesy of the Lib Dems. Don’t ever let them forget that.

We didn’t win, but all was not lost.

We reminded people of the strength there still is in this Labour movement of ours when we fight as one, unions and Party together, for the things we hold in common.

We stood up for thousands of NHS staff like those with us today who saw Labour defending the values to which they have devoted their working lives.

And we spoke for the country – for patients and people everywhere who truly value the health service Labour created and don’t want to see it broken down.

Conference, our job now is to give them hope.

To put Labour at the heart of a new coalition for the NHS.

To set out a Labour alternative to Cameron’s market.

To make the next election a choice between two futures for our NHS.

They inherited from us a self-confident and successful NHS.

In just two years, they have reduced it to a service demoralised, destabilised, fearful of the future.

The N in NHS under sustained attack.

A postcode lottery running riot – older people denied cataract and hip operations.

NHS privatisation at a pace and scale never seen before.

Be warned – Cameron’s Great NHS Carve-Up is coming to your community.

As we speak, contracts are being signed in the single biggest act of privatisation the NHS has ever seen.

398 NHS community services all over England – worth over a quarter of a billion pounds – out to open tender.

At least 37 private bidders – and yes, friends of Dave amongst the winners.

Not the choice of GPs, who we were told would be in control.

But a forced privatisation ordered from the top.

And a secret privatisation – details hidden under “commercial confidentiality” – but exposed today in Labour’s NHS Check.

Our country’s most-valued institution broken up, sold off, sold out – all under a news black-out.

It’s not just community services.

From this week, hospitals can earn up to half their income from treating private patients. Already, plans emerging for a massive expansion in private work, meaning longer waits for NHS patients.

And here in Greater Manchester – Arriva, a private bus company, now in charge of your ambulances.

When you said three letters would be your priority, Mr Cameron, people didn’t realise you meant a business priority for your friends.

Conference, I now have a huge responsibility to you all to challenge it.

Every single month until the Election, Jamie Reed will use NHS Check to expose the reality.

I know you want us to hit them even harder – and we will.

But, Conference, I have to tell you this: it’s hard to be a Shadow when you’re up against the Invisible Man.

Hunt Jeremy – the search is on for the missing Health Secretary.

A month in the job but not a word about thousands of nursing jobs lost.

Not one word about crude rationing, older people left without essential treatment.

Not a word about moves in the South West to break national pay.

Jeremy Hunt might be happy hiding behind trees while the front-line of the NHS takes a battering.

But, Conference, for as long as I do this job, I will support front-line staff and defend national pay in the NHS to the hilt.

Lightweight Jeremy might look harmless. But don’t be conned.

This is the man who said the NHS should be replaced with an insurance system.

The man who loves the NHS so much he tried to remove the tribute to it from the Opening Ceremony of the Olympic Games.

Can you imagine the conversation with Danny Boyle?

“Danny, if you really must spell NHS with the beds, at least can we have a Virgin Health logo on the uniforms?”

Never before has the NHS been lumbered with a Secretary of State with so little belief in it.

It’s almost enough to say “come back Lansley.”

But no. He’s guilty too.

Lansley smashed it up for Hunt to sell it off with a smile.

But let me say this to you, Mr Hunt. If you promise to stop privatising the NHS, I promise never to mispronounce your name.

So, Conference, we’re the NHS’s best hope. Its only hope.

It’s counting on us.

We can’t let it down.

So let’s defend it on the ground in every community in England.

Andrew Gwynne is building an NHS Pledge with our councillors so, come May, our message will be: Labour councils, last line of defence for your NHS.

But we need to do more.

People across the political spectrum oppose NHS privatisation.

We need to reach out to them, build a new coalition for the NHS.

I want Labour at its heart, but that means saying more about what we would do.

We know working in the NHS is hard right now, when everything you care about is being pulled down around you.

I want all the staff to know you have the thanks of this Conference for what you do.

But thanks are not enough. You need hope.

To all patients and staff worried about the future, hear me today: the next Labour Government will repeal Cameron’s Act.

We will stop the sell-off, put patients before profits, restore the N in NHS.

Conference, put it on every leaflet you write. Mention it on every doorstep.

Make the next election a referendum on Cameron’s NHS betrayal.

On the man who cynically posed as a friend of the NHS to rebrand the Tories but who has sold it down the river.

In 2015, a vote for Labour will be a vote for the NHS.

Labour – the best hope of the NHS. Its only hope.

And we can save it without another structural re-organisation.

I’ve never had any objection to involving doctors in commissioning. It’s the creation of a full-blown market I can’t accept.

So I don’t need new organisations. I will simply ask those I inherit to work differently.

Not hospital against hospital or doctor against doctor.

But working together, putting patients before profits.

For that to happen, I must repeal Cameron’s market and restore the legal basis of a national, democratically-accountable, collaborative health service.

But that’s just the start.

Now I need your help to build a Labour vision for 21st century health and care, reflecting on our time in Government.

We left an NHS with the lowest-ever waiting lists, highest-ever patient satisfaction.

Conference, always take pride in that.

But where we got it wrong, let’s say so.

So while we rebuilt the crumbling, damp hospitals we inherited, providing world-class facilities for patients and staff, some PFI deals were poor value for money.

At times, care of older people simply wasn’t good enough. So we owe it to the people of Stafford to reflect carefully on the Francis report into the failure at Mid-Staffordshire Foundation NHS Trust.

And while we brought waiting lists down to record lows, with the help of the private sector, at times we let the market in too far.

Some tell me markets are the only way forward.

My answer is simple: markets deliver fragmentation; the future demands integration.

As we get older, our needs become a mix of the social, mental and physical.

But, today, we meet them through three separate, fragmented systems.

In this century of the ageing society, that won’t do.

Older people failed, struggling at home, falling between the gaps.

Families never getting the peace of mind they are looking for, being passed from pillar to post, facing an ever-increasing number of providers.

Too many older people suffering in hospital, disorientated and dehydrated.

When I shadowed a nurse at the Royal Derby, I asked her why this happens.

Her answer made an impression.

It’s not that modern nurses are callous, she said. Far from it. It’s simply that frail people in their 80s and 90s are in hospitals in ever greater numbers and the NHS front-line, designed for a different age, is in danger of being overwhelmed.

Our hospitals are simply not geared to meet people’s social or mental care needs.

They can take too much of a production-line approach, seeing the isolated problem – the stroke, the broken hip – but not the whole person behind it.

And the sadness is they are paid by how many older people they admit, not by how many they keep out.

If we don’t change that, we won’t deliver the care people need in an era when there’s less money around.

It’s not about new money.

We can get better results for people if we think of one budget, one system caring for the whole person – with councils and the NHS working closely together.

All options must be considered – including full integration of health and social care.

We don’t have all the answers. But we have the ambition. So help us build that alternative as Liz Kendall leads our health service policy review.

It means ending the care lottery and setting a clear a national entitlement to what physical, mental and social care we can afford – so people can see what’s free and what must be paid for.

It means councils developing a more ambitious vision for local people’s health: matching housing with health and care need; getting people active, less dependent on care services, by linking health with leisure and libraries; prioritising cycling and walking.

A 21st century public health policy that Diane Abbott will lead.

If we are prepared to accept changes to our hospitals, more care could be provided in the home for free for those with the greatest needs and for those reaching the end of their lives.

To the district general hospitals that are struggling, I don’t say close or privatise.

I say let’s help you develop into different organisations – moving into the community and the home meeting physical, social and mental needs.

Whole-person care – the best route to an NHS with mental health at its heart, not relegated to the fringes, but ready to help people deal with the pressure of modern living.

Imagine what a step forward this could be.

Carers today at their wits end with worry, battling the system, in future able to rely on one point of contact to look after all of their loved-one’s needs.

The older person with advanced dementia supported by one team at home, not lost on a hospital ward.

The devoted people who look after our grans and grand-dads, mums and dads, brothers and sisters – today exploited in a cut-price, minimum wage business – held in the same regard as NHS staff.

And, if we can find a better solution to paying for care, one day we might be able to replace the cruel ‘dementia taxes’ we have at the moment and build a system meeting all of a person’s needs – mental, physical, social – rooted in NHS values.

In the century of the ageing society, just imagine what a step forward that could be.

Families with peace of mind, able to work and balance the pressures of caring – the best way to help people work longer and support a productive economy in the 21st century.

True human progress of the kind only this Party can deliver.

So, in this century, let’s be as bold as Bevan was in the last.

Conference, the NHS is at a fork in the road.

Two directions: integration or fragmentation.

We have chosen our path.

Not Cameron’s fast-track to fragmentation.

But whole-person care.

A One Nation system built on NHS values, putting people before profits.

A Labour vision to give people the hope they need, to unite a new coalition for the NHS.

The NHS desperately needs a Labour win in 2015.

You, me, we are its best hope. It’s only real hope.

It won’t last another term of Cameron.

NHS.

Three letters. Not Here Soon.

The man who promised to protect it is privatising it.

The man who cut the NHS not the deficit.

Cameron. NHS Conman.

Now more than ever, it needs folk with the faith to fight for it.

You’re its best hope. It’s only hope.

You’ve kept the faith.

Now fight for it – and we will win.