Home » Posts tagged 'duty of candour'

Tag Archives: duty of candour

Fears and smears – wilful inattention from healthcare journalists?

In an article today in the Independent, subtitled “Fears and smears”, Ed Miliband MP writes:

“They want to distract attention from the issues that matter. With the support of a determined section of the press, they have decided that mudslinging matters more than the futures of millions of families across this country.”

Discussion of the NHS is an incredibly sensitive area and yet it has been done incredibly badly by many journalists and politicians.

Mid Staffs was an unacceptable disaster. It was THE low point in the NHS.

Relatives of loved ones have shown incredible bravery and resilience in the face of an unbelievably tragic intolerable event.

For many, the issues in Mid Staffs appeared to be simply brushed under the carpet for political purposes, and real patients and relatives suffered.

The claim over professional codes and a duty of candour

On Thursday, Jeremy Hunt gave an answer on Mid Staffs on the BBC programme ‘Question Time‘. Regarding making it easier for people to speak out, “people are going to be given protection in their professional codes which have happened before.”

Mr Hunt is therefore speaking as if this has sprung up from nowhere.

Not true, even from the briefest scan of ‘Five Minute Digest – Duty of Candour’ in ‘Pulse Today‘:

The claim that Burnham opposed an inquiry

There are two inquiries – when you read the rest of this article, be mindful that

- November 2009 – Robert Francis QC begins hearing evidence in private as part of his independent inquiry

- February 2010 – Robert Francis QC publishes his independent inquiry report into the poor care at Mid Staffordshire Foundation Trust

- May 2010 – Change of government and Health Secretary

- November 2010 – The public inquiry begins to hear evidence

- December 2011 – The public inquiry finishes hearing evidence after more than 12 months

In Question Time last week, regarding Mid Staffs, Mr Hunt explained, “Your party opposed a public inquiry. Andy Burnham decided to oppose a public inquiry.”

The Executive Summary of the Report of the public inquiry, published in 2013, is here.

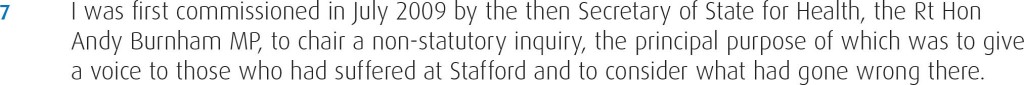

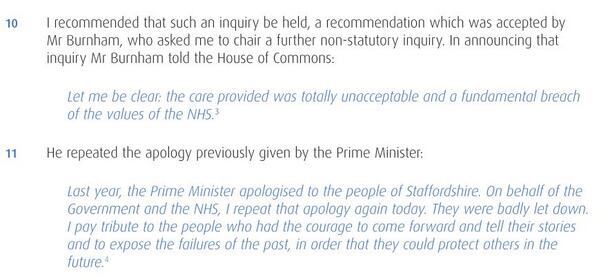

The way the original private inquiry was set up by Andy Burnham MP, the then Secretary of State for Health, is described in the 2013 Francis report as follows.

A new Government was elected in the UK in May 2010. The way in which Andrew Lansley MP, the then Secretary of State for Health, set up a public inquiry is provided in the 2013 Francis report as follows.

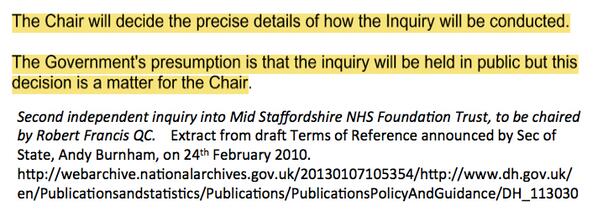

This actually came as no surprise, as Andy Burnham MP had already stated that the second Inquiry would be held in public, as cited here.

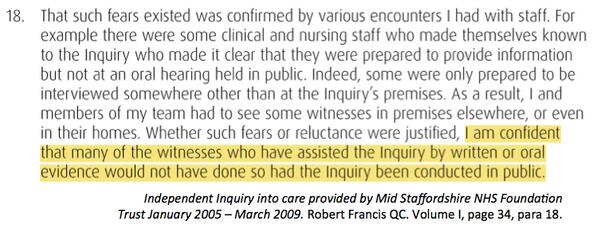

Francis himself did not want the first inquiry to sit in public for the first time, and is even reported as being satisfied with the arrangements, as cited here.

The problem here is in the media at large the genuine message that Burnham set up the first inquiry in 2009 ‘to give patients a voice’ has been swamped by the toxic meme from some, and they know who they are, that ‘Burnham blocked an inquiry’.

The claim that Burnham never apologised

Another blatant classic lie is that Burnham has never ‘apologised for Mid Staffs’.

This is addressed too, as cited here.

The claim that Burnham resisted an inquiry under the Inquiries Act

Burnham obviously did not have any powers as Secretary of State for Health after the General Election of May 2010. The decision for the second public inquiry comes after that date.

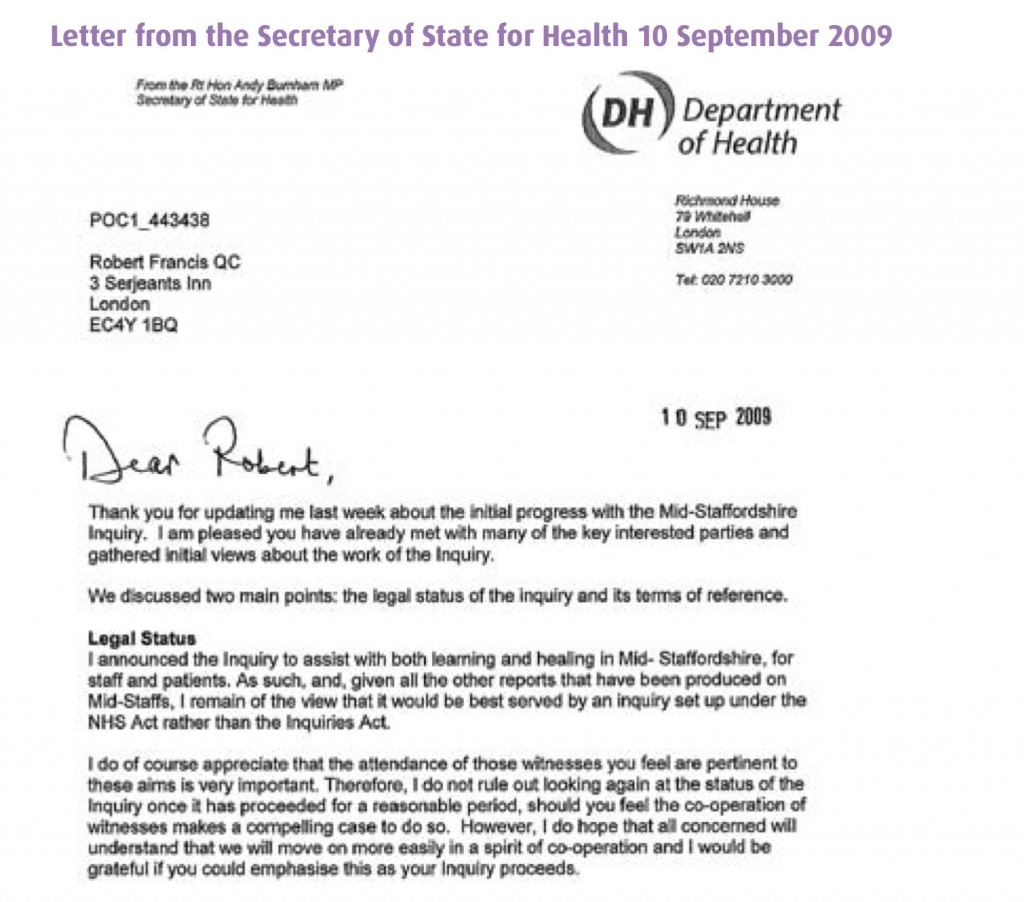

It has been claimed furthermore that Andy Burnham MP resisted his inquiry to take place under the auspices of the Inquiries Act, but Burnham did actually leave it all times to be directed by Francis, the Chair of the Inquiry.

This legally is a somewhat obtuse claim, as it was a Labour government which enacted the Inquiries Act in 2005 in the first place.

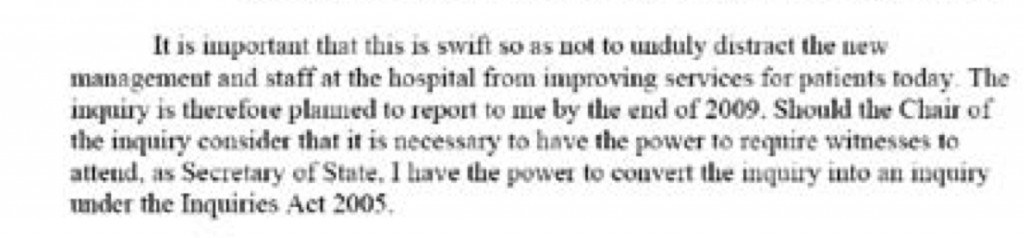

In Appendix 1 of the bundle of documents entitled “Independent Inquiry into care provided by Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust January 2005-March 2009 Volume 1″ Appendix 2, Andy Burnham MP as the then Secretary of State for Health in his Written Ministerial statement (21 July 2009) first cites his perceived need to set up an inquiry “swift so as not to unduly distract the new management and staff at the hospital from improving services for today”, but that he has the power to convert the Inquiry to one under the Inquiries Act should the Chair of the Inquiry (Robert Francis QC) should demand it.

This exact text of the statement is indeed evidenced in Hansard, for 21 July 2009 Column WS188 as per here.

In Appendix 2 of the bundle of documents entitled “Independent Inquiry into care provided by Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust January 2005-March 2009 Volume 1″ Appendix 2, Andy Burnham MP as the then Secretary of State for Health repeats (10 September 2009) his willingness for his inquiry to be set up under the Inquiries Act not the NHS Act.

This is the evidence that Burnham gave to Francis 2 on 6 Sep 2011, page 178:

Indeed, parsimoniously, the option of ‘converting another form of inquiry’ into an Inquiry as under the Inquiries Act at any time is clearly good application of the law, under section 15 Inquiries Act (2005).

The claim that ‘wilful neglect’ legislation is a fundamental new shift in the law

The Berwick Report itself was all about constructive organisational learning, and only introducing a statutory crime of ‘wilful neglect’ for the most extreme cases.

Some vocal campaigners in Mid Staffs clearly desire targeted retributive justice, but the media thus far have refused to cover why the law of ‘wilful neglect’ in the form of section 44 Mental Capacity Act (2005) has failed to see a flurry of successful criminal prosecutions in Mid Staffs. We have instead discusssed it here. ‘Wilful neglect’ is NOT a fundamental new shift in the law, unless it can now be applied to adults with full capacity.

The claim that ‘there was a culture of cruelty in the NHS and no-one noticed”

Staff in various NHS Trusts have voiced loudly their resentment as being targeted in some sort of ‘hate campaign’.

Jeremy Hunt last week specifically referred to how a culture of cruelty ‘became normal in our NHS’, not in any particular Trust.

as cited in Hansard 19 November 2013.

Summary

The problem in this imbalance of irresponsible reporting is that it creates a culture of fear in NHS nurses, even in those ‘who have nothing to hide’. It is not a mature discussion of the technical problems in the law. It is instead ‘red meat’, ‘dog whistle’ politics of the worst kind, of a particular political inclination. As a result of memes about the Inquiry, candour and putting clinical staff in the clink, an irresponsible media has diverted attention from important issues.

By allowing copious air time for lies, the important discussion of why A&E is experiencing difficulties, a lack of a stated minimum level of safe staffing, why social care cuts have been so dangerous, or why NHS 111 has failed so dramatically, have not been explored in any level of acceptable detail.

Sadiq Khan MP tried valiantly to bring up how staffing levels had been so low, and ‘without the doctors and nurses, it’s all talk and no action.” But the stench of the narrative above diverted him from discussing the critical issues as much as he would have liked, although he did get in an official statistic about a cut in nursing numbers.

Real staff are none-the-wiser. Patient campaigners are led down the river without a paddle. Voters are completely bamboozled.

This is an unholy disgusting mess from those responsible. Call it wilful inattention.

Thanks to the public tweets of @gabrielscally for many of the extracts cited in the article.

Why speaking out safely and safe staffing are important moral issues for the NHS

A culture where staff and patients can speak openly about successes and failures in the NHS, as well as more specifically on safe staffing issues, is essential for the NHS to move forward. Perhaps most intriguingly, the failure of the English law to cherish the need to ‘speak out safely’ in the NHS can be tracked back to four Acts of parliament ranging in the last thirty years uptil the present day.

A culture where staff and patients can speak openly about successes and failures in the NHS, as well as more specifically on safe staffing issues, is essential for the NHS to move forward. Perhaps most intriguingly, the failure of the English law to cherish the need to ‘speak out safely’ in the NHS can be tracked back to four Acts of parliament ranging in the last thirty years uptil the present day.

The focus recently has tended to be about whether things would or would not work, and have either been economic or regulatory in perspective.

The Health and Social Care Act (2012), all 493 pages of it, is fundamentally a statutory instrument which proposes the mechanism for competitive tendering in the NHS (through the now infamous section 75), the financial failure regimes, and the regulatory mechanisms to oversee an emboldened market. It is therefore a gift for the corporate lawyers. It does, though, successfully mandate in law the abolition of the National Patient Safety Agency in s. 281.

There is therefore not a single clause on patient safety in this voluminous document. Patients, and the workforce of the NHS, are however at the heart of the NHS.

The language has been overridden by economic concepts misapplied. “Sustainability” is a very good example. Too often, sustainability has been used as a synonym for ‘maintained’, usually as a precursor for an argument about shutting down NHS services. It quite clearly from the management literature means a future plan of an entity with due regard to its whole environment.

Discussion about regulators can lead to a paralysis of policy.

No sanctions against Doctors have yet been made by the GMC over Mid Staffs, which does rather appear to be a curious paradox given the widespread admissions of undeniably ‘substandard care’. The regulator needs to have the confidence of the public too. One of their rôles is commonly cited to be to ‘protect the public‘, and this is indeed enshrined in law under s.1(1A) Medical Act (1983).

It is of regulatory interest how precisely the GMC ‘protected the public’ over Mid Staffs, whatever the operational justifications of their legal processes in this particular case.

Strictly speaking, promoting the safety of the public might include promoting the ability of clinical staff ‘to speak out safely’, and this could be an important manifestation of a core legal objective of that particular regulator?

On the other hand, confidence in the regulator is never achieved by any regulator on the basis of conducting “show trials“. This can be always be a big danger, as GMC cases on occasions attract wider general media interest. This will, of course, be to the detriment of defendants with complicated mental health issues.

There is little fundamental dispute about the need for clinicians to be open about medical errors in their line of work. Even the Compensation Act (2006), if you need to cite the law, provides that an apology does not mean an admission of liability in section 2.

There can be disputes about upon whom the ‘duty of candour’ should fall, whether this might be the Trust or an individual clinician, and who is going to enforce it.

But just because there are legal issues about the practicality of it, a civilised society must use the law to reflect the society it wishes for.

There is currently, for example, a statutory duty for company directors to maximise shareholder dividend of a company with due regard to the environment (as per s.172 Companies Act (2006)). There is no corresponding duty for hospitals to minimise morbidity or mortality on their watch.

“Whistleblowers” are often accused of raising their complaints too late.

Whistleblowers can find themselves becoming alien for NHS organisations they are devoted to.

Often, there is a ‘clipboard mentality’ where ‘colleagues’ will raise issues to discredit the whistleblowers. Often these ‘colleagues’ are protecting their own back. Regulators should not collude in such initiatives.

And yet it is clear that the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998 fails both patients and whistleblowers.

There are ways to bring about change. Most often regulation is not in fact the answer.

A cultural change is definitely needed, and this appears to go beyond corrective mechanisms through English jurisprudence.

This in the alternative requires staff and patients from within the NHS prioritising speaking out safely.

The information which can be provided by ‘speaking out safely’ should be treated like gold dust – and be used for improvement for patient safety in the NHS, as well as in the performance management of all clinicians involved.

Arguably the precise information is much more useful than an estimate such as the ‘hospital standardised mortality ratio’ which does not operate on a case-by-case basis anyway.

A new-found desire to speak openly might also include a wider policy discussion about safe staffing levels. Regulating a minimum staffing level might shut down important debates about ‘what is safe’, such as the skill mix etc. And yet there are equally important issues about how to prioritise this in the law.

The hypothesis that unsafe staffing levels or poor resources generally lead to poor patient safety in some foci of the NHS has not been rejected yet. It’s essential that managers allow staff to be listened to, if they have genuine concerns. Not everything is vexatious.

Most of all, society has to be seen to reward those people who have been strong in putting the patient first.

Small steps such as Trusts in England supporting the Nursing Times’ “Speak Out Safely” campaign are important.

Critically, such support is vital, whatever political ideology you hail from.

It could well be that the parliamentary draftsmen produce a disruptive innovation in jurisprudence, such that speaking out safely is correctly valued in the English law, and thenceforth in the behaviour of the NHS.

Hopefully, an initial move with the recent drafting of a clause of the “legal duty of candour” in the Care Bill (2013) we will begin to see a fundamental change in approach at last.

A ‘paradox of regulation’ in the NHS has opened the neoliberal floodgates

At 493 pages, the ‘Health and Social Care Act’ is a massive piece of legislation. Writing a blogpost on it would be like trying to summarise the contents of ‘War and Peace’ in a single tweet. From that perspective, it might seem as if the NHS is over-regulated, and certainly the number of guidelines and policies relating to the NHS has exploded. The Act has no provisions on patient safety, apart from the abolition of the “National Patient Safety Agency”, and yet Monitor is expected to publish a huge armoury of regulation of ‘competitive activity’ in the market. The full-frontal marketisation, together with outsourcing and privatisation of the NHS, is considered totally unacceptable to many reasonable onlookers, especially socialists. Market failure is a very important concept in economics, on the other hand. Market failure is a concept within economic theory describing when the allocation of goods and services by a free market is not efficient. That is, there exists another conceivable outcome where a market participant may be made better-off without making someone else worse-off. Market failures can be viewed as scenarios where individuals’ pursuit of pure self-interest leads to results that are not efficient – that can be improved upon from the societal point-of-view. The first known use of the term by economists was in 1958, but the concept has been traced back to the Victorian philosopher Henry Sidgwick. The general consensus, now, is not that there is a desperate drive for yet ‘more regulation’ at any cost, but there is a need for a higher standard of effective regulation in the NHS, to which not only top CEOs in NHS management can have full access. This is particularly poignant since the volume of budgeted NHS litigation claims has in fact exploded in recent years.

There is an ideological divide between those on the left-wing and those on the right-wing. The Conservatives promoted themselves on ‘light touch regulation’ at roughly the same time as the Financial Services and Markets Bill was going through parliament. There are two crucial issues now for the adequate regulation of the NHS. Firstly, all parties have a concern in patient safety. The previous failures of the Health Service Ombudsman’s office and that of CQC could be, and even now possibly, be pinned down directly on a lack of sufficient resources needed for them to fulfil their functions, and existing staff there would prefer not to amplify any suggestion that they are failing patients. Neoliberals also have an interest in patient safety, as failures in patient safety threaten competitive advantage, ultimately the profitability of private healthcare companies. Secondly, the failure of adequate market regulation in the water industry (and indeed the privatised utilities) still remains powerfully sobering for any ‘users’ of the National Health Service, a group within the general public formerly known as ‘patients’.

Employment is the first clear example of the ‘law in action’ in the NHS. The NHS, by its own admission, has decided to use compromise and confidentiality agreements in settlement with outgoing employees to prevent them pursuing unfair dismissal claims as is their statutory right. When it comes to a minimum staffing level, the usual riposte from the Right is that the complete answer involves ‘the staffing mix’. However, this is disingeniously to divert from the issue that there is an unsafe staffing level. Despite the fierce debates about the use and statistical reliably of hospital standardised mortality ratios (HMSRs), the clear evidence is that unsafe doctors:bed ratios can shove up the HSMR for weekends both in this jurisdiction and abroad (Dr Foster report 2010-2011, Prof Brian Jarman (personal communication by twitter.)) While the Left (and the Unions particularly) see the minimum staffing levels of nurses as ensuring a safe minimum standard for hospital safety, the Right (and neoliberals) invariably see the safe minimum staffing level as part of ‘the race to the bottom’ to maximise shareholder profitability. Staffing remains the number one issue where more effective regulation in the NHS could make a massive impact on patient safety, and indeed it is likely that this will be addressed as well as the legal duty of candour for hospitals, in Don Berwick’s wideranging report due out tomorrow.

The turbo-charged implementation of the economic market, rejected by true socialists, presents formidable problems for the regulation of the NHS. Traumatic lessons from other sectors, especially the privatised utilities, are particularly helpful here. There are currently twenty one private water companies operating in England, answerable to their shareholders. They are overseen by economic regulator OFWAT. Before 1989, water supply in England and Wales had been in the hands of 10 public regional water authorities, which were then sold off. They are private companies, many are owned by banks, private equity firms or foreign investment funds, like the main supermarkets.Thames Water, for instance, has been owned by Kemble Water Holdings – an investment consortium led by Australian banking and finance group Macquarie, with recent shareholdings taken by the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority and the China Investment Corporation. This democratic deficit of course makes many people angry, whereas the Unions have been the target of malicious smears from virtually all sectors of the media. Similarly, when Cheung Kong Infrastructure was buying Northumbria Water at the end of 2011, it sold Cambridge Water to South Staffordshire Water. South Staffordshire is wholly owned by the US based Alinda Infrastructure Fund.

OFWAT calculates the average water and sewerage bill in England and Wales at £340 for 2011-12, compared to £236 when water was privatised in 1989-90. The Health and Social Care Act and the regulations for implementing it change the nature of the NHS to allocate NHS resources into the private sector, to maximise profitability for shareholders. Private competitive tendering as the default option has seen major contracts being awarded to private sector corporates. The tragedy of this is that some private providers have an atrocious performance record in outsourcing, but because they are able to make slick bids appear to be implementing a ‘winning formula‘ in rent seeking behaviour from the current neoliberal Coalition. Priorities change from patient care to ensuring corporate rights, from spending directly on health care to investor dividends. The UK NHS becomes much more like the corporate-benefit US health care system which has very high spending while many people have no health care.

Any Qualified Provider is a procurement model that CCGs can use to develop a register of providers accredited to deliver a range of specified services within a community setting. The model aims to reduce bureaucracy and barriers to entry for potential providers. The US/EU free trade agreement has been launched, formally called the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). When TTIP negotiations are completed, unless the neoliberal Coalition manage to negotiate successfully an exemption for the NHS, corporations will have the right to sue the UK government for any attempts at ‘reversals’ that limit future corporate profits. In terms of “ownership”, most of our power generating companies, our airports and ports, our water companies, many of our rail franchises and our chemical, engineering and electronic companies, our merchant banks, an iconic chocolate company – Cadbury, our heavily subsidised wind farms, a vast amount of expensive housing and many, many other assets, all disappeared into foreign ownership. No mainstream party appears to be making any progress in this. Debbie Abrahams, Labour MP for Oldham East and Saddleworth, as a lone voice almost, has lodged a question from David Cameron regarding what exemption (if any) has been negotiated (recorded in Hansard here), and it turns out that Debbie Abrahams has now received a rather unclear reply.

In the EU, there are concerns that liberalising public procurement markets, combined with measures to protect foreign investors from government action, could constrain the power of national governments to decide how public services are provided. Concerns about the status and future of the NHS have been raised in the UK by people from many quarters other than in the Socialist Health Association. In particular, some commentators have claimed that measures to open up the NHS to competition would be made irreversible under the TTIP if its investor protection regime required US companies to be compensated in the event of a change of policy. This is of course a very dangerous situation. The liberalisation of the NHS market through the US-EU would be accelerated through a US-EU Free Trade Agreement. This is something which some corporates have been working very hard on ‘behind the scenes’. To dismiss this issue as scaremongering by the Socialist Health Association, which is supposed to uphold socialist principles and oppose further marketisation and privatisation, would be to turn a blind eye to all the legal evidence and judgments.

The legal arguments against further privatisation of the NHS are overwhelmingly strong, and there is a distinct lack of effective regulation of the NHS currently. Such poor regulation, whilst a boon for profiting private health providers, offends what is actually in the ‘best interests’ of patients.

This should massively concern socialists.

We can’t go on like this.