Home » Posts tagged 'Cure the NHS'

Tag Archives: Cure the NHS

Safe staffing, Keogh and the Nursing Times “Speak out safely” campaign

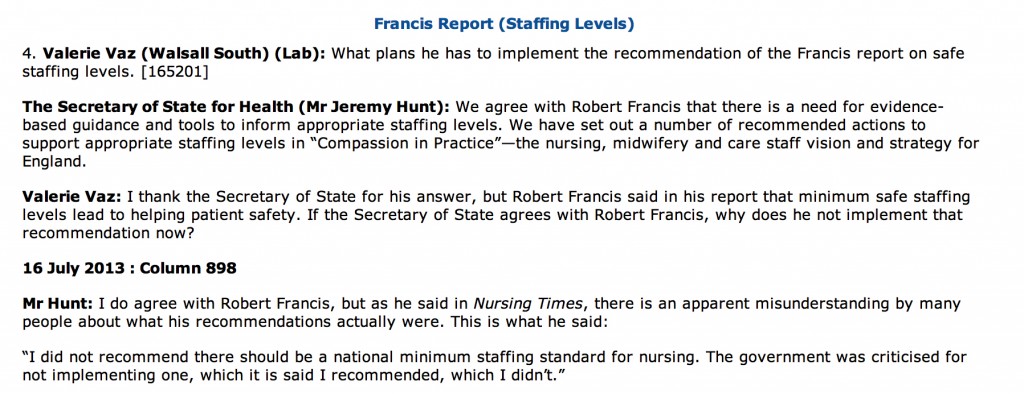

Despite clear differences in opinion about what has happened in the past, patient groups, Andy Burnham, Jeremy Hunt, the Unions, bloggers, experts, other patients, whistleblowers, and relatives at face value appear to want the same thing: a safe NHS where you do not go into hospital as a risky event in itself. The issue of safe staffing in nursing has become the totemic pervasive core issue of secondary care safety, and no amount of parliamentary time one suspects will ever do proper justice to it. In reply to a question from Valerie Vaz, who is herself on the Health Select Committee, Jeremy Hunt immediately quoted the Nursing Times and the Francis Report (from Tuesday 16 July 2013):

The aim of the Nursing Times’ Speak Out Safely (SOS) campaign is to help bring about an NHS that is not only honest and transparent but also actively encourages staff to raise the alarm and protects them when they do so.

They want:

- The government to introduce a statutory duty of candour compelling health professionals and managers to be open about care failings

- Trusts to add specific protection for staff raising concerns to their whistleblowing policies

- The government to undertake a wholesale review of the Public Interest Disclosure Act, to ensure whistleblowers are fully protected.

A very impressive gamut of organisations have supported the “Nursing Times Speak Out Safely” campaign, including Cure the NHS, the Florence Nightingale Foundation, the Foundation of Nursing Studies, Mencap Whistleblowing Hotline, Patients First, Public Concern at Work, Queen’s Nursing Institute, Royal College of Nursing, Unite (including the Community Practitioners and Health Visitors Association and Mental Health Nurses Association), and WeNurses. Also, for example, according to the Royal College of Midwives, maternity staff must be able to publicly raise concerns about the safety of mother and babies without fear of reprisal from their employers, according to the Royal College of Midwives. This college has been the latest organisation to support the Speak Out Safely campaign. They are calling for the creation of an open and transparent NHS, where staff can raise concerns knowing they will be handled appropriately and without fear of bullying.

The pledge of the Speak Out Safely campaign of Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust is a pretty typical example of the way in which this campaign has successfully reached out to all people who have the focused aspiration of patient safety.

“This trust supports the Nursing Times Speak Out Safely campaign. This means we encourage any staff member who has a genuine patient safety concern to raise this within the organisation at the earliest opportunity.

Patient safety is our prime concern and our staff are often best placed to identify where care may be falling below the standard our patients deserve. In order to ensure our high standards continue to be met, we want every member of our staff to feel able to raise concerns with their line manager, or another member of the management team. We want everyone in the organisation to feel able to highlight wrongdoing or poor practice when they see it and confident that their concerns will be addressed in a constructive way.

We promise that where staff identify a genuine patient safety concern, we shall not treat them with prejudice and they will not suffer any detriment to their career. Instead, we will support them, fully investigate and, if appropriate, act on their concern. We will also give them feedback about how we have responded to the issue they have raised, as soon as possible.

It is not disloyal to colleagues to raise concerns; it is a duty to our patients. Misconduct or malpractice should never be tolerated, while mistakes and poor practice may reveal a colleague needs more training or support, or that we need to change systems or processes. Your concerns will be dealt with in an open and supportive manner because we rely on you to ensure we deliver a safe service and ensure patient safety is not put at risk. We also want this organisation to have the confidence to admit to mistakes and to use them as learning opportunities.

Whether you are a permanent employee, an agency or temporary staff member, or a volunteer, please speak up when you feel something is wrong. We want you to be able to Speak Out Safely.”

The Keogh report is in its entirety is an apolitical report, and is very constructive. It identifies problems which Keogh’s team (which currently consists of some brilliantly talented Clinical Fellows) have a realistic chance of tackling. Despite criticisms that Hunt has turned up the ‘political heat’ on this issue, there is a feeling that Labour and Andy Burnham MP should either ‘put up or shut up’. If you park aside the mudslinging over the 13,000 ‘needless deaths’ from irresponsible journalism from parts of the media, the current Department of Health has surely begrudgingly have to be given some credit for instigating appropriate responses such as the Keogh review, and a Chief Inspector of Hospitals. There has been a real effort to clear up the methodology of estimating mortality figures, and while methodology issues will persist, an approach which fully involves and acknowledges the views of patients, whatever their political affiliations, is the only way forward.

As an immediate response to the terms of reference to protect patients from harm, Keogh thrust high up the importance of instigating changes to staffing levels and deployment; and dealing with backlogs of complaints from patients. Keogh identified a basic deficiency in effective performance management in the 14 NHS Trusts under investigation, and these basic performance management techniques are now commonplace in successful corporates. These constitute understanding issues around the trust’s workforce and its strategy to deal with issues within the workforce (for instance staffing ratios, sickness rates, use of agency staff, appraisal rates and current vacancies) as well as listening to the views of staff; Keogh laid down a number of “ambitions”. In ambition 6, Keogh argued that nurse staffing levels and skill mix should appropriately reflect the caseload and the severity of illness of the patients they are caring for and be transparently reported by trust boards.

The review teams especially found a recurrent theme of inadequate numbers of nursing staff in a number of ward areas, particularly out of hours – at night and at the weekend. This was compounded by an over-reliance on unregistered staff and temporary staff, with restrictions often in place on the clinical tasks temporary staff could undertake. There were particular issues with poor staffing levels on night shifts and at weekends. There were also problems in some hospitals associated with extensive use of locum cover for doctors.This observation is interesting as at the end of day an over-reliance on agency staff in both private and public sector from a performance management perspective will guarantee the NHS not getting the best out of its staff, and will further impede hospital CEOs from meeting their ‘efficiency targets’. As set out in the “Compassion in Practice”, Directors of Nursing in NHS organisations should use evidence-based tools to determine appropriate staffing levels for all clinical areas on a shift-by-shift basis. This means that a statutory minimum may be the inappropriate sledgehammer for an important nut. It is proposed that boards should sign off and publish evidence-based staffing levels at least every six months, providing assurance about the impact on quality of care and patient experience. The National Quality Board will shortly publish a ‘How to’ guide on getting staffing right for nursing. Whilst it is easy to argue against a national minimum number for nurses, as one can easily argue that it might encourage a race-to-the-bottom with managers gaming the system such that they only provide the minimum to run their Trust, most people, irrespective of the strong-held and important views of professionals within the nursing profession, believe that running a service with too few nurses is simply too risk for the remaining nurses. At times of high demand, Trusts need to be adaptable and flexible enough to cope, as anyone who has been involved in acute care in national emergencies has been involved (“critical incidents”).

Staffing was a recurrent pathology in the 14 Trusts under investigation. In Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, it was argued that the Trust needs to review current staffing levels for nursing and medical staff. In Buckinghamshire NHS Trust, the panel had a concern over staffing levels of senior grades, in particular out of hours. In Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust, it was found that staffing in some high risk wards needs urgent review. For the Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust, inadequate qualified nurse staffing levels were identified on some wards, including two large wards which needed to be reviewed in light of concerns raised by the panel. For North Lincolnshire and Goole NHS Foundation Trust, there were concerns over the staffing of key elements of acute care, including recruitment of staff and maintenance of adequate staffing levels and skill mix on the wards. In North Cumbria University Hospital NHS Trust, inadequate staffing levels was identified, as well as an over-reliance on locum cover in some areas of the Trust.

For East Lancashire NHS Trust, the review team considered that staffing levels were low for medical and nursing staff when compared to national standards. Registrar cover and medical staffing in the emergency department was considered poor (this is medical ‘code’ for an overreliance on juniors at Foundation level), and levels of midwifery staff were considered poor too. Certain clinical concerns raised by staff have not been addressed, including known high mortality at the weekends. Whilst some of these actions will take longer to address entirely, assurance in respect of patient flows in A&E and concerns over staffing in the midwifery unit had already been sought by the CQC. For Medway NHS Foundation Trust, a top priority was made of teviewing staffing and skill mix to ensure safe care and improve patient experience, emphasising yet again that there might be false security to be derived from just looking at the overall number. For Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, significant concerns around staffing levels at both King’s Mill Hospital and Newark Hospital and around the nursing skill mix, with trained to untrained nurse ratios considered low, at 50:50 on the general wards. Finally, for United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust, inadequate staffing levels and poor workforce planning particularly out of hours were discovered; concern over the low level of registered nursing staff on shifts in some wards during the unnannounced visit out of hours was escalated to CQC. Further investigation is underway.

This is a matter for all the political parties to get to the bottom of urgently. Party affiliations and tribal politics threaten real substantial progress in this area for all those who work in this area. This is not the time for energised disputes about political leadership in organisations. This is most certainly a time for action. Both the Francis report into the failures of care at Mid Staffs, and The Keogh Review into high hospital mortality rates, highlight how important the right skills mix and sufficient numbers of staff are to providing top quality care. Having the right staff cover is increasingly important out of hours – at evenings and weekends. With all political parties urging a need to work ‘harder and smarter’, or generally under the rubric of working more ‘efficiently’, this is a harsh climate, due to shrinking budgets as the cost of healthcare rises, and because of demands for £20 billion of so-called efficiency savings. Of course, the public are not involved in a genuine public debate at the moment which does not depict the ageing population as a budgetary ‘burden’ on the society, instead pumping in a carefree way billions into the HS2 project with its unclear business case. Billions more have been wasted on a chaotic, unnecessary top down reorganisation of the NHS; the National Audit Office has latterly criticised for the Government for going ‘over-budget’ on these bureaucratic reforms. Frontline staff are obviously rightly angry that this is money that they feel this is money that could and should have gone towards actually caring for patients.

The tragedy is that it really feels as if the NHS has never known, or unlearnt at great speed, basic performance management. One can argue until the cows come home how in this managerial-heavy approach to the NHS such management is extremely poorly done in such a way the CIPD would feel ashamed at possibly. The NHS will deserve to have problems in recruiting the best managers for the NHS so long as the climate of performance management, perhaps affected by an obsession for targets, remains deeply unappealing. It is recognised that good performance management helps everyone in the organisation to know hat the organisation is trying to achieve, their role in helping the business achieve its goals, the skill and competencies they need to fulfil; their role, the standards of performance required, how they can develop their performance and contribute to development of the organisation, how they are doing, and when there are performance problems and what to do about them. The general consensus is that, if employees are engaged in their work they are more likely to be doing their best for the organisation. An engaged employee is someone who:

The actual reality is that currently spending pressures mean that many health workers, sadly, are losing their jobs. Financial pressures are building up in the NHS just as the demand for healthcare and its cost is rising – trusts are being asked to make unconscionable savings. Trusts such as Barts Healthcare are in severe trouble, and the contribution of the failed policy of PFI is a massive scandal in itself. This perfect storm will hit standards of patient care hard, and is the direct consequences of decisions made by various recent governments – not by hardworking NHS staff. The only thing which is set up to work in the Act, apart from outsourcing (section 75) and raising massively the private cap (section 164(1)(2A)) of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 is the legal precision of the various failure or insolvency regimes. In any other sector, this would fall under wrongful or fraudulent trading. Except, it’s the NHS. It does economic activity in a very special way. As the shift in economic and political power shifts from a state well-funded comprehensive healthcare system to a fragmented disorganised piecemeal private integrated system in the next few decades, patient safety must take priority even if not a top priority seemingly in business plans. Initiatives such as the Nursing Times ‘Speak out Safely’ campaign is one of those vital ‘checks and balances’ to ensure that the NHS is working with and for patients and not against them. This means the NHS valuing staff as a top priority, as social capital is the most important thing in any organisation.

The Health and Social Care (2012) was not about patient safety: implications for the Keogh report

The Health and the Social Care Act (2012) is a massive tome. It actually reads, for lawyers who are well acquainted with such statutory instruments, like a huge patchwork quilt of commercial and corporate law strands. While voluminous, at 473 pages, it has two critical clauses. The first is section 75, and its concomitant now famous Regulations, which provides the statutory basis for procurement contracts in the NHS to be put up for price competitive tendering as the default option, thus fixing the NHS in a competitive market of an economic activity. This is of course the mechanism for outsourcing NHS services into the private sector, and indeed the vast majority of contracts have now been won by the private sector. This was widely predicted, as the private sector have skills and resources to make slicker bids, irrespective of the bid they ultimately deliver, to transfer a much higher proportion of “NHS services” into the profit-making private sector. All of this costs the NHS more money sadly, as while it may not matter to you ‘who provides your services’, you’re in trouble if the private provider goes bust, and you’re not paying for anything at anywhere near cost-price because of the mark-up for profit. This section 75 clause acts in tandem with section 164(1)(2A) which allows any NHS hospital to receive up to 50% of its income from private sources. Thus the Act, and the £2.4 NHS “reforms”, have been a bonanza for the private sector, and disastrous from the perspective of a state-provider of universal, comprehensive healthcare.

Patient safety is in fact only mentioned once in the Act, in clause 281. That is in reference to the abolition of the National Patient Safety Agency. The National Reporting and Learning System which was hosted by NPSA has a two year stint at Imperial College Hospital NHS Trust, while a tender process is scoped and developed by the Board. NPSA’s responsibilities concerning patient safety will transfer to the NHS England.

The Health and Social Care Act 2012 (c. 7) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is the most extensive reorganisation of the structure of the National Health Service in England to date. It proposes to abolish NHS primary care trusts (PCTs) and Strategic Health Authorities (SHAs). The Act’s proposals were not discussed during the 2010 general election campaign and were not contained in the 20 May 2010 Conservative – Liberal Democrat coalition agreement, which declared an intention to “stop the top-down reorganisations of the NHS that have got in the way of patient care”. However, within two months a white paper outlined what the Daily Telegraph called the “biggest revolution in the NHS since its foundation”. The white paper, Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS, was followed in December 2010 by an implementation plan in the form of Liberating the NHS: legislative framework and next steps. The bill was introduced into the House of Commons on 19 January 2011, and received its second reading, a vote to approve the general principles of the Bill, by 321-235, a majority of 86, on 31 January 2011.

The British Medical Association opposed the bill, and held its first emergency meeting in 19 years, which asked the government to withdraw the bill and reconsider the reforms. A later motion of no confidence in Lansley by attendees at the Royal College of Nursing Conference in 2011, however, succeeded, with 96% voting in favour of the motion. Nurses have consistently been opposed to the the “efficiency savings” measures being undertaken across the NHS, with many raising concerns of their material impact on frontline medical services. “People will die”, Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet, warned in March 2012, as he predicted “unprecedented chaos” as a result of the reforms, with a leaked draft risk-assessment showing that emergencies would be less well managed and the increased use of the private sector would drive up costs.

The Bill is now Law, and where are the measures to deal with this longrunning problem of patient safety, particularly in the acute setting? There are none. The media was sent into overdrive in portraying the NHS has a “death machine”, despite the best attempts of nurses and Doctors to run the service under difficult conditions. The publication of the damning Keogh Report (“Report”), which spelt out the failings of 14 hospital trusts which did not quote “13,000 “needless deaths” since 2005″, is despite exhaustive pre-briefing to the media. The Report depicts a situation in certain trusts where patient safety is poor, with no reference to what action has been taken by the Government and their civil service to remedy this since the General Election in May 2010, which the Conservatives lost. Sir Bruce Keogh, the NHS’s Medical Director, will describe how each hospital let its patients down through poor care, medical errors and failures in management, but the Report is as if the clinical regulatory bodies do not exist, the General Medical Council, the Nursing and Midwifery Council and the Care Quality Commission. How they have escaped blame for this reported ‘scandal’ is incredible, although one suspects the media will catch up with them eventually. It might be that the media for whatever reason known to them do not feel the clinical regulators are in “the firing line”, despite being supposed to be responsible for patient safety, in the same way that lawyers are not responsible for the global financial crisis despite being supposed to regulated on the safety of financial instruments.

From a management point of view, the Keogh Report serves a function for convincing the public of a need to take patient safety extremely seriously. However, to sell the Keogh Report as “Do you now see the need for the NHS reforms?” maybe hitting a target but missing a crucial point. The NHS reforms are all to do with outsourcing and eventual privatisation of the NHS. They are nothing to do with patient safety, as even right-wing think tanks and their spokesmen have previously conceded in public. In fact, it is worse than that. The £2.4 reorganisation which nobody voted for, but which private healthcare companies extensively lobbied for, was a reckless missed opportunity to put resources into something other than frontline care, and the opportunity cost of this piece of legislation will continue to haunt the general public for many years. Unfortunately, the media and the members of the Establishment, some members of which have tenuous links with the institutional shareholders in private healthcare companies, will be more than aware of this hard fact. The Conservatives are desperate to pin every conceivable woe of the NHS on Andy Burnham, and every interview which Burnham now does must feel like “Groundhog Day” for him. He has nothing much more in his defense. Meanwhile, the Conservatives are exasperated that they have been unable to get the Burnham scalp, but there are as yet unresolved issues about what Government departments have done about NHS complaints in the last three years since May 2010. The bottom line is that the Health and Social Care Act is nothing to do with patient safety: even safety campaigners in the NHS know this, and they know of the even worse battle now facing them, of a fragmented privatised NHS which is even harder to regulate from that point of view. The NHS reforms, and more specifically the Health and Social Care Act which underpins them, have nothing to do with patient safety. More disturbingly, the Keogh report, when eventually published, will not stop ‘another Francis’, and it is entirely the Government’s fault we are in this stupid ridiculous position.

Is the answer to abject failure of medical regulation yet more regulation?

There are parallels with the discussion of whether the financial sector was too lightly regulated in the events in the global financial crash. This also happened under Labour’s watch. And Labour got a fair bit of blame for that, despite the Conservatives appearer to wish the regulation in that sector to be even “lighter”. Despite uncertainties about the number of people who actually died at Mid Staffs, for statistical reasons, there is a consensus there are clear examples of care which fell below the standard of the duty-of-care. Such breach caused damage, within an accept time period of remoteness, causing different forms of damage. The problem in this chain of the tort of regulation is that there appears to have been little in the way of damages. It is clear that the regulatory bodies have found it difficult to process their cases in a timely fashion in such a way that even some members of the medical profession and the public have found distressing and unproductive. The medical regulators are, however, fiercely concerned about their reputation, which is why any rumour that you have beeen involved in a cover up, ahead of patient safety, is potentially deadly.

There is a mild sense of panic amongst government ranks, with the introduction of a ‘Chief Inspector of Hospitals’, conducting OFSTED type assessments, and a “legal duty of candour”. It is proposed that this new legal duty might apply to institutions rather than individuals, unless Don Berwick, currently running for Governor of Massachussetts, has any better ideas in the interim. Here is the first problem; the GMC and other clinical councils take a punitive retributive approach (if not restorative), rather than rehabilitative, and Sir Robert Francis QC has emphasised that this is a wider culture malaise where it is difficult to find ‘scapegoats’. Organisations such as Cure however point to the fact that nobody appears to have taken responsibility, and are reported to have a shortlist of people who they’d like to see be in the firing line over Mid Staffs. The GMC is not in the business of blaming organisations, only individuals. In fact, its code (GMC’s “Duty of a Doctor”) is set up so that Doctors can report other Doctors to the GMC, and even report Managers to the GMC.

There is a possibility that NHS managers are not even aware of the professional code of the Doctors who comprise a key part of the workforce, but paragraph 56 of the GMC’s “Duties of a Doctor” is pivotal in demanding Doctors see their patients on the basis of clinical need. This is this clause which provides the tension with the A&E “four hour wait target”, but it is perhaps rather too late for medics to flex their professional muscles over this years after its introduction.

56. You must give priority to patients on the basis of their clinical need if these decisions are within your power. If inadequate resources, policies or systems prevent you from doing this, and patient safety, dignity or comfort may be seriously compromised, you must follow the guidance in paragraph 25b.

Paragraph 25b provides the trigger where Doctors have a duty in their Code to let their NHS manager know:

25. You must take prompt action if you think that patient safety, dignity or comfort is or may be seriously compromised. (b) If patients are at risk because of inadequate premises, equipment*or other resources, policies or systems, you should put the matter right if that is possible. You must raise your concern in line with our guidance11 and your workplace policy. You should also make a record of the steps you have taken.

And indeed following the legal trail, according to the CPS, a person holding “public office” can have committed the offence of “misconduct in a public office” if he or she does not act on such concerns, according to current guidance:

Misconduct in public office is an offence at common law triable only on indictment. It carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. It is an offence confined to those who are public office holders and is committed when the office holder acts (or fails to act) in a way that constitutes a breach of the duties of that office. The Court of Appeal has made it clear that the offence should be strictly confined. It can raise complex and sometimes sensitive issues. Prosecutors should therefore consider seeking the advice of the Principal Legal Advisor to resolve any uncertainty as to whether it would be appropriate to bring a prosecution for such an offence.

(current CPS guidance)

It is a legal point whether a NHS CEO meets the definition of a person holding “public office”. However, few will see little point in a Doctor, however Junior or Consultant, reporting a hospital manager to the GMC for lack of resources. The GMC indeed have a confidential helpline where Doctors can voice concerns about patient safety, even other colleagues, but this itself is fraught with practical considerations, such as when data are disclosed beyond confidentiality and consent, or a duty for the GMC not to encourage an avalanche of vexatious and time-consuming complaints either.

Indeed, the whole whistleblower affair has blown up because whistleblowers feel they have to make a disclosure for the purpose of patient safety in an unsupporting environment, often directly to the media, because nobody listens to them at best, or they get subject to detrimental behaviour (humiliation or bullying, for example) at worst. Clinical staff will not wish to get involved in lengthy GMC investigations about their hospital, and it would be interesting to see how many the actual number which have resulting in any form of sanction actually is. This is even amidst the backdrop that more than half of nurses believe their NHS ward or unit is dangerously understaffed, according to a recent survey, reported in February 2013. The Nursing Times conducted an online poll of nearly 600 of its readers on issues such as staffing, patient safety and NHS culture. Three-quarters had witnessed what they considered “poor” care over the past 12 months, the survey found. Understaffing in clinical wards has been identified as a cause of nurses working at a pace beyond what they are comfortable with, and the subsequent effects on patient safety are succinctly explained by Jenni Middleton (@NursingTimesEd) and colleagues in their video for the “Nursing Times Speak Out Safely” campaign.

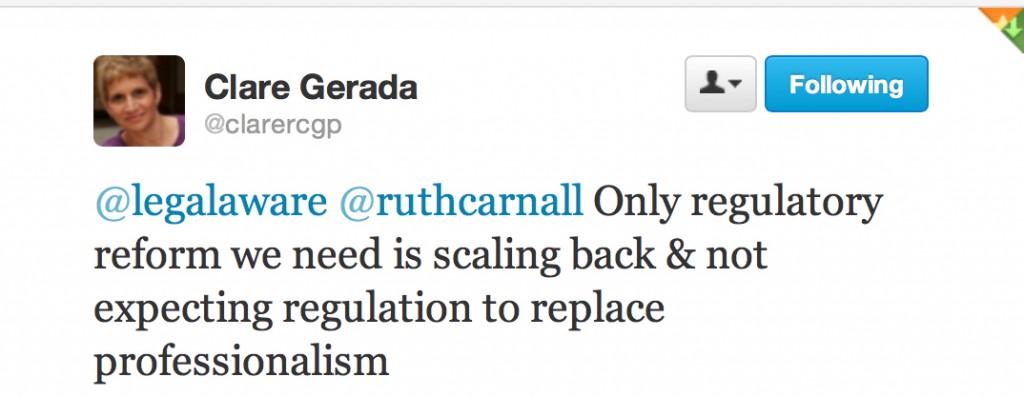

In the same way, the cure for recession may not be more spending (this is a moot point), the answer to a failure of medical regulation may not be yet further regulation. The temptation is to add an extra layer of regulation, such as an OFHOSP body which goes round investigating hospitals, but we have already introduced a ‘Chief Inspector of Hospitals’. At worst, further regulation encourages a culture of intimidation and secrecy, and Prof Clare Gerada clearly does not believe the NHS being caught up in yet further regulation is practicable or advisable:

And yet most would agree, following Mid Staffs and the revelations over CQC at the weekend that ‘doing nothing is NOT an option’ (while conceding that a “moral panic” response cannot be appropriate either.) The fundamental problem is that this policy gives all the impression of being designed in response to a crisis, how acute medics work in ‘firefighting’. Likening patient safety to the economy, it might be more fruitful to focus attentions to the other end of the system. This is the patient safety equivalent of turning attention from redistributive (or even punitive) taxation to predistribution measures such as the living wage. Some advocates call for a greater emphasis on compassion, and reducing the number of admissions seen in the Medical Admissions Unit or A&E, but in a sense we are coming full-circle again in the underlying argument of an under-resourced ward being an unsafe one. Transplant on this a political mantra that the main parties have had divergent views about whether NHS spending is adequate now or has been adequate before, in apparent contradiction to the nearly £3bn savings which were not ploughed back into patient care. or the £2bn suddenly found for the complex implementation of the Health and Social Care Act (2012). The existing regulatory mechanism for complaints to be made about under-resourcing affecting patient safety is there, but the intensity of the incentive for professionals using this mechanism appears to be low. Professionals will argue that they have a professional duty to maintain patient safety regardless of yet further regulation, but professionals have reported the mission creep of deprofessionalism in the NHS for some time now. Here, the medical professions have a mechanism of holding the NHS to account, and, if adverse reports were investigated quickly and acted upon, it is possible that NHS CEOs are not overly rewarded for failure. But if this mechanism is considered unfeasible, along with a “new improved” performance management system incentivising somehow ‘whistleblowing’, it’s back to the drawing board yet again.

“Lessons learned” – If every unemployment statistic is a tragedy, what was every ‘excess death’ at Mid Staffs?

It never fails to amaze me how certain policy strands run in parallel along a disastrous course, but silos in journalism mean that you’ll never get people joining the dots.

One example of this is the competitive tendering in legal services which Chris Grayling MP is currently shoehorning through, despite overwhelming opposition from lawyers including QCs. Everytime the unemployment figures up, or we have another revival in youth employment, Chris Grayling used to be the guy on TV saying that ‘every statistic is of course a personal tragedy’. Curiously you never get this phrase said about any excess death from the NHS which happened out of the ordinary. The concept that it is impossible to measure excess deaths at all will be alien to any professional in clinical negligence, who will be able to follow through the well-worn logic of duty-of-care of a clinician, failure of that duty causing breach, and that breach causing damage provided that there is not remoteness. We all know that the media is prone to hysteria, and indeed John Prescott once advised me not to believe everything written about ‘one’ in the papers. And an issue undoubtedly is that some are using what happened at Mid Staffs for their own agendas. You’d be forgiven for thinking some reports have the sole intention of shutting down the entire NHS as a national health service, blow all its credibility to smithereens, and to prepare its purchase price for the lowest bidder in a Government which has relish in outsourcing and privatisating the State infrastructure.

However, the sensationalism which was embraced whether there were any ‘excess deaths’ or not is perhaps distasteful at best, and frankly rude at worst. Mortality ratios are supposed to be the ‘smoke alarm’, but now that the inferno has happened, it is not time to remove the batteries from the smoke detector. The public inquiries at Mid Staffs I feel were essential. I don’t feel that this is an issue which could have been discussed behind closed doors ‘in camera’. It might be feasible to hold no-one accountable as the ‘culture’ is so widespread, but that has not led professionals to escape liability ever before for fundamental breaches in care, such as poor note-keeping, unprompt investigations, poor conduct and communication, from the professional regulators. The frustration has been there appears to have been very little accountability, and this is significant whether one feels the role of the justice system should be fundamentally restorative, retributive or rehabilitative. A certain amount of hysteria has instead engulfed proceedings at Mid Staffs, with the recently reported hostile behaviour towards Julie Bailey, remarkable campaigner and founder of ‘Cure the NHS’.

However, Julie has never wanted to ‘Kill the NHS’, but is deeply hurt about what happened to her Mum. Deb Hazeldine is very hurt about what happened to her mum. Any reasonable daughter would. These are times for reports of personal tragedies. Whilst we all have to move on, it is important to acknowledge accurately the distress of what happened, and this is precisely what we achieved in the Francis Inquiries. The accounts in those Inquiries are not figments of anyone’s imagination. It is even possible that we may have to learn from what happened there for other NHS Trusts. There is a trail of logic which goes that ‘efficiency savings’ were in fact cuts which included relative staff shortages, despite more being spent on the NHS budget overall including for salaries for certain personnel; this meant that key critical frontline staff were overstretched, there were genuine clinical events in patient safety which went beyond ‘near misses’, but they were not adequately dealt with. The Francis Inquiries should not be used to draw closure on the matters for the Labour administration, which I broadly supported. The reaction to the situation, a real one of personal tragedy, should not in my view a retweet of a blog which says that standard mortality ratios are unreliable, however correct that blog might be. This for me is not in any way personal – I like and respect very much people on all sides of what has been a highly charged discussion. I have known some of them for ages, and I will continue to support them publicly and in private.

We are not at the end of the solution of what happened in Mid Staffs, and for the time-being we should honestly recognise that.

If every unemployment statistic is a tragedy, what was every 'excess death' at Mid Staffs?

It never fails to amaze me how certain policy strands run in parallel along a disastrous course, but silos in journalism mean that you’ll never get people joining the dots.

One example of this is the competitive tendering in legal services which Chris Grayling MP is currently shoehorning through, despite overwhelming opposition from lawyers including QCs. Everytime the unemployment figures up, or we have another revival in youth employment, Chris Grayling used to be the guy on TV saying that ‘every statistic is of course a personal tragedy’. Curiously you never get this phrase said about any excess death from the NHS which happened out of the ordinary. The concept that it is impossible to measure excess deaths at all will be alien to any professional in clinical negligence, who will be able to follow through the well-worn logic of duty-of-care of a clinician, failure of that duty causing breach, and that breach causing damage provided that there is not remoteness. We all know that the media is prone to hysteria, and indeed John Prescott once advised me not to believe everything written about ‘one’ in the papers. And an issue undoubtedly is that some are using what happened at Mid Staffs for their own agendas. You’d be forgiven for thinking some reports have the sole intention of shutting down the entire NHS as a national health service, blow all its credibility to smithereens, and to prepare its purchase price for the lowest bidder in a Government which has relish in outsourcing and privatisating the State infrastructure.

However, the sensationalism which was embraced whether there were any ‘excess deaths’ or not is perhaps distasteful at best, and frankly rude at worst. Mortality ratios are supposed to be the ‘smoke alarm’, but now that the inferno has happened, it is not time to remove the batteries from the smoke detector. The public inquiries at Mid Staffs I feel were essential. I don’t feel that this is an issue which could have been discussed behind closed doors ‘in camera’. It might be feasible to hold no-one accountable as the ‘culture’ is so widespread, but that has not led professionals to escape liability ever before for fundamental breaches in care, such as poor note-keeping, unprompt investigations, poor conduct and communication, from the professional regulators. The frustration has been there appears to have been very little accountability, and this is significant whether one feels the role of the justice system should be fundamentally restorative, retributive or rehabilitative. A certain amount of hysteria has instead engulfed proceedings at Mid Staffs, with the recently reported hostile behaviour towards Julie Bailey, remarkable campaigner and founder of ‘Cure the NHS’.

However, Julie has never wanted to ‘Kill the NHS’, but is deeply hurt about what happened to her Mum. Deb Hazeldine is very hurt about what happened to her mum. Any reasonable daughter would. These are times for reports of personal tragedies. Whilst we all have to move on, it is important to acknowledge accurately the distress of what happened, and this is precisely what we achieved in the Francis Inquiries. The accounts in those Inquiries are not figments of anyone’s imagination. It is even possible that we may have to learn from what happened there for other NHS Trusts. There is a trail of logic which goes that ‘efficiency savings’ were in fact cuts which included relative staff shortages, despite more being spent on the NHS budget overall including for salaries for certain personnel; this meant that key critical frontline staff were overstretched, there were genuine clinical events in patient safety which went beyond ‘near misses’, but they were not adequately dealt with. The Francis Inquiries should not be used to draw closure on the matters for the Labour administration, which I broadly supported. The reaction to the situation, a real one of personal tragedy, should not in my view a retweet of a blog which says that standard mortality ratios are unreliable, however correct that blog might be. This for me is not in any way personal – I like and respect very much people on all sides of what has been a highly charged discussion. I have known some of them for ages, and I will continue to support them publicly and in private.

We are not at the end of the solution of what happened in Mid Staffs, and for the time-being we should honestly recognise that.