Home » Posts tagged 'behaviour'

Tag Archives: behaviour

Dementia is caused by diseases of the brain

“Dementia Friends” is an initiative from the Alzheimer’s Society and Public Health England. In this series of blogpost, I take an independent look at each of the five core messages of “Dementia Friends” and I try to explain why they are extremely important for raising public awareness of the dementias.

That ‘Dementia is caused by diseases of the brain’ may seem like a pretty innocuous statement.

There have been numerous attempts at looking at the numbers of the different causes of dementia, varying in overall success over the years.

One study “Prevalence of dementia subtypes: A 30-year retrospective survey of neuropathological reports” came from Hans Brunnström, Lars Gustafson, Ulla Passant and Elisabet Englundemail in 2008.

The authors investigated the distribution of neuropathologically defined dementia subtypes among individuals with dementia disorder.

The neuropathological reports were studied on all patients (n?=?524; 55.3% females; median age 80, range 39–102 years) with clinically diagnosed dementia disorder who underwent complete post mortem examination including neuropathological examination within the Department of Pathology at the University Hospital in Lund, Sweden, during the years 1974–2004.

The neuropathological diagnosis was Alzheimer’s disease in 42.0% of the cases, vascular dementia in 23.7%, dementia of combined Alzheimer and vascular pathology in 21.6%, and frontotemporal dementia in 4.0% of the patients.

Different types of dementia (and factsheets about them) are summarised in this page from the Alzheimer’s Society.

Part of the problems with the statement comes from the definition of ‘dementia’.

For example, a WHO definition is provided thus:

“Dementia is a syndrome – usually of a chronic or progressive nature – in which there is deterioration in cognitive function (i.e. the ability to process thought) beyond what might be expected from normal ageing. It affects memory, thinking, orientation, comprehension, calculation, learning capacity, language, and judgement. Consciousness is not affected. The impairment in cognitive function is commonly accompanied, and occasionally preceded, by deterioration in emotional control, social behaviour, or motivation.”

However academics and practitioners over the years have squabbled over the nuances of the definition. Should the definition compulsorily include memory in the early stages? Most people I think would agree ‘no’, if only because of the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia where individuals present with an insidious progressive change in behaviour and personality in the early stages can report no changes in their memory. And can it be reversible?

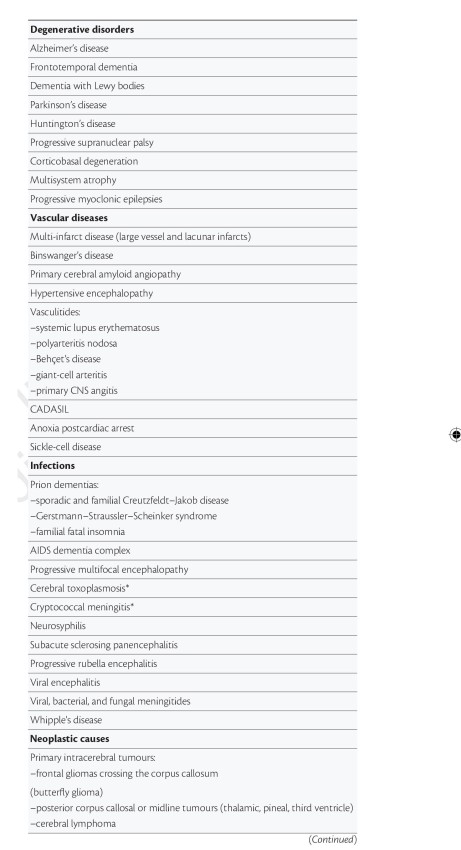

This is Prof John Hodges’ list of the dementias presented in the current Oxford Textbook of Medicine, which is helpful.

But problems in metabolism from the rest of the body can cause problems in brain function. The list is a long one, and an introduction to this topic here.

And antibodies raised in cancers which haven’t revealed themselves yet can cause a dementia-like picture.

Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis (PLE) is a rare disorder characterized by personality changes, irritability, depression, seizures, memory loss and sometimes dementia.

This diagnosis is difficult because clinical markers are often lacking, and symptoms usually precede the diagnosis of cancer or mimic other complications.

A range of tumours outside of the brain can be implicated in this complicated conditions, including oesophagus, lung, bladder, colon, lung, thymus and breast.

This is for example a helpful summary table from Gultekin and colleagues in Brain. 2000 Jul;123 ( Pt 7):1481-94.

They can be associated with markers in the fluid surrounding the spinal cord, and in magnetic resonance imaging of the brain. But to call them “diseases of the brain” would be a massive over-simplification?

And there might not be a biological disease at all causing profound symptoms.

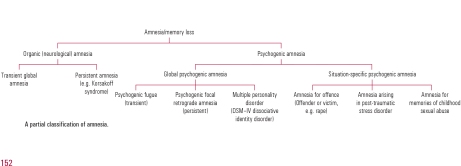

McKay and Kopelman’s article “Psychogenic amnesia: when memory complaints are medically unexplained” in Advances in psychiatric treatment (2009) [vol. 15, 152–158 doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.105.001586] is an extremely useful introduction.

Amnesia is a particular cognitive problem. Amnesia has been defined as ‘an abnormal mental state in which memory and learning are affected out of all proportion to other cognitive functions in an otherwise alert and responsive patient’ (Victor 1971).

According to them, “A number of terms have been used to describe medically unexplained amnesia, including ‘hysterical’, ‘psychogenic’, ‘dissociative’ and ‘functional’. Each requires the exclusion of an underlying neurological cause and the identification of a precipitating stress that has resulted in amnesia. Unfortunately, the presence of amnesia may make it difficult to identify the stress until either informants have come forward or the amnesia itself has resolved”.

They helpfully provide this scheme for looking at the causes.

Hans J. Markowitsch looked at “Psychogenic amnesia” in an extremely useful article in NeuroImage 20 (2003) S132–S138.

Markowitsch, a world leader in memory, kicked off with the realisation that sometimes a disease of the brain, in terms of an identifiable pathology, often could not be located for quite profound symptoms.

“Commonly, memory disturbances are related to organic brain damage. Nevertheless, especially the old psychiatric literature provides numerous examples of patients with selective amnesia due to what at that time was preferentially named hysteria and which implied that both environmental circumstances and personality traits influence bodily and brain states to a considerable degree. Awareness of the existence of relations between cognition, soma, and psyche has increased especially in recent times

and has created the research branch named cognitive neuropsychiatry.”

Mizutani and colleagues (2014) have indeed reported a case which could to all intents-and-purposes have been caused by a disease of the brain.

Its cause is an overactive thyroid, a gland in the neck.

“We report the case of a 20-year-old Japanese woman with no psychiatric history with apparent dissociativesymptoms. These consisted of amnesia for episodes of shoplifting behaviors and a suicide attempt, developing together with an exacerbation of Graves’ hyperthyroidism. Patients with Graves’ disease frequently manifest various psychiatric disorders; however, very few reports have described dissociative disorder due to this disease. Along with other possible causes, for example, encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroid disease, clinicians should be aware of this possibility.”

Dissociative disorders can take many forms – see this factsheet from Mind.

It is thought that dissociative amnesia is amnesia caused by trauma or stress, resulting in an inability to recall important personal information.

Therefore ‘Dementia is caused by diseases of the brain’ is not in fact an innocuous statement. But for the purposes of “Dementia Friends”, it is.

Further references

Victor M, Adams RD, Collins GH (1971) The Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome. F.A. Davis.

Mizutani K, Nishimura K, Ichihara A, Ishigooka J. Dissociative disorder due to Graves’ hyperthyroidism: a case report. (2014) Gen Hosp Psychiatry, Mar 19. pii: S0163-8343(14)00073-5. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.03.010.

Dr Shibley Rahman : review of "Keeper" by Andrea Gillies

Andrea Gillies argues that dementia is ill-understood and remains so stigmatized that the government fails to treat it with the same urgency as other illnesses such as cancer. The historical lack of prioritization of dementia in the UK is indeed based on substantial fact and is utterly surprising, but it seems that all political parties have now pledged to remedy this despite the necessary age of financial austerity.

In her book ‘Keeper’, Andrea Gillies describes moving but unsentimental terms the day-to-day experience of caring for Nancy, her mother-in-law affected by Alzheimer’s disease. I felt the book was outstanding, explaining how a person is changed because of a real underlying disease. This book is the only one I know of which charts brilliantly a person’s cognition, personality and behaviour extremely accurately, and which is entirely in keeping of decades of research of the progression of the disease in cognitive neuroscience.

The Wellcome Trust and George Orwell prizes – richly deserved

The book has already won two prestigious awards – the Wellcome Prize, in recognition of its dispassionate analysis of the effects the disease has on the brain, and the George Orwell Prize, recognizing the author’s anger at a medical and social care system that is failing to support sufferers and their carers. The Orwell Prize is the pre-eminent British prize for political writing, and previous winners include Raja Shehadeh and Peter Hennessy.I think that the anger should be viewed in terms of improving dementia care, something which I feel passionate about, rather than any criticisms of the system. Confidence will only be undermined unless we address coherently these weaknesses.

On the Orwell panel, English PEN director Jonathan Heawood, writer Francine Stock and Andrew Holgate, literary editor of The Sunday Times, provided that Keeper is a ‘startlingly honest and vivid‘ work which goes beyond being just a memoir to examine issues such as identity and memory. ‘[Gillies] argues powerfully for change in the way we deal with age and senility, a looming political issue for the 21st century,’ the panel also commented.

While some Alzheimer’s books, such as John Bayley’s “Elegy for Iris,” are enmeshed with memories of the person before illness, Andrew Gillies intersperses her narrative with smart, very accessible narratives on the history and science of the Alzheimer’s syndrome.

Overview

At the outset of ‘Keeper’, Nancy wakes “to find that she has aged 50 years overnight, that her parents have disappeared, that she does’t know the woman in the mirror, nor the people who claim to be her husband and children, and has never seen the series of rooms and furnishings that everyone around her claims insistently is her home.”

The transition from full cognition to the cognitive and the neuropsychiatric deficits found in Alzheimer’s disease is likened to stepping through “Alice’s looking glass”.

Andrea Gillies explains that the most distressing period is when you are moving from one side to the other:

“She had one foot through the looking glass and she couldn’t make those two worlds – dementia reality, and normal life – gel at all …It was really quite science fiction in a way. Complete strangers coming into the house and saying ‘How are you today? Shall we go and have a walk?’ Obviously your reaction is going to be ‘What are you talking about? I’ve no idea who you are.’ She would awake in the morning not knowing who the man in the next bed was and she was afraid. Strangers would come into her bedroom and hand her clothes she had never seen before.”

Andrea Gillies and her husband, facing his parents’ declining health, purchased a spacious Victorian home on the Scottish coast large enough for all of them: Andrea Gillies, her husband, their three children and Nancy and her husband, Morris. The property had several acres; they kept dogs, a large garden, chickens and horses. From inside the house, they could see the rocky coast and windblown sea. ??This book is a journal of life in this wild location, in which Andrea Gillies tracks Nancy’s progression through a powerfull disease.

Memory

Early on, Nancy could express herself, but she needed help dressing, a sign of the disease’s grip. In the new house her difficulties increased: her short-term memory was degraded so that she had a hard time recognizing where she was. Indeed, problems in spatial memory is supposed to be a recognized hallmark early symptom of the disease, as the disease is centred around the medial temporal lobe initially (a part of the brain near the ear). The pattern of memory deficit is exactly as described in the seminal work of Ribot (1881), where memory for old events is relevantly preserved, compared to the encoding of new memories which is relatively impaired. “She couldn’t map her new home. Every morning she woke up thinking she had just arrived and she didn’t know where the kettle was or how to get to the bathroom. This made her angry and afraid,” according to Gillies.

In the book, it is also described that doctors initially prescribed Nancy drugs designed to stay the loss of memory, but it is not clear that these had much effect. The evidence has been that the cognitive effects of a popular group of dementia symptom-improving drugs for memory and attention, the cholinesterase inhibitors, have overall been modest, but the effects have been variable amongst recipients (with some patients, and their immediates, noting remarkable improvements).

The environment

Personally, I found the account of the enormous significance of the environment to patients with dementia incredibly powerful. the resemblance of Nancy’s new home to her childhood home provided, instead of comfort, confusion: she sometimes insisted her long-dead father was nearby. It swiftly becomes clear that they cannot look after themselves in their new home, so Gillies and her husband decide to sell up their own family home and buy a big Victorian house on a remote Scottish peninsula, moving their 10-old-year son, Jack, and his two teenage sisters into new schools and creating two separate establishments in one home, connected by a communal kitchen. The role of empowering patients with their environment instead of being unsettling can potentially be utilized to improve the quality-of-life of patients with their dementia, but this work has yet to make the huge advances it is worthy of in my opinion. Amazing progress has already been made, on a positive note.

Personality and behaviour

What makes this book special is that although it is very much an exploration of episodic memory, its loss and the subsequent erosion of personality, it is also a very useful chronicle of the effects that the onset of Alzheimer’s disease can unleashe on the extended family. It is also a chronicle of Gillies’ own unravelling, as the exhausting, realities of a carer’s role overwhelm her. Most powerful, however, is Nancy’s own voice, carefully recorded by Gillies in nightly diary entries, a voice that is at times cantankerous, bewildered, but defiant. Reading these monologues, we get very close to understanding what it feels like to experience this illness.

As the disease progresses through the brain, other areas, controlling personality and behaviour in the frontal lobes, can change a person in dementia. Some patients are mystically described by immediates as ‘changing for the better’, but Gillies is unable to give such a view of Nancy. Nancy deteriorates from a somewhat benignly forgetful doting grandmother to a raging harpy, who slaps her granddaughters, calls her beloved grandson variously a bastard, arsehole and bitch, cannot remember how to use cutlery, prefers not to wash, tucks used bits of loo paper up her sleeve, squats on the floor to pee and hides her own turds behind paperbacks in the bookshelves (“the kind of discovery that’s unexpected late at night when you’re looking for something to read”). For me, the accounts of late Alzheimer’s disease were very reminiscent of what happens, in terms of profound behavioural and personality changes, in early behavioural frontal variant frontotemporal dementia. On one occasion recounted in the book, Nancy surprises Australian guests over breakfast when she marches through the dining room wearing nothing more than a large pair of lilac briefs; they are too polite to complain.) The transformation of her mother-in-law’s personality sets Gillies on an investigation into the way the brain controls personality, concluding that identity is biological. “Selfhood isn’t something separate from your biological self,” she writes. “The brain is where your self is made.”

Reviews

“Andrea Gillies’s account of living with Alzheimer’s is the perfect fusion of narrative with enough memorable science not to choke you. It’s a fantastic book – down to earth and darkly comic in places. The judges found it compelling.” Jo Brand, Chair of the judges of the Wellcome Prize, 2009

“A wonderful book ¬– honest, upsetting, tender, sometimes angry, often funny – which takes us on a journey into dementia and explores what it means to be human.” Deborah Moggach

“Terrific, terrifying, absolutely powerful in every choice of word, every sentence… completely unflinching” Quentin Cooper

“This is one of the most moving and important books that I have read on Alzheimer’s.” John Bayley

“Thoughtful, informative and true… a very good, very necessary book.” Sir Richard Eyre, Patron of the Alzheimer’s Research Trust

“Andrea Gillies is a brilliant prose stylist with a poet’s facility for metaphor and a brave wit born of exasperation and sadness.” Professor Raymond Tallis

You can purchase “Keeper: a book about memory, identity, isolation, Wordsworth and cake…” by Andrea Gillies (www.shortbooks.co.uk) here.

Dr Shibley Rahman trained in cognitive neurology at Cambridge and in London. Although he is not a practising physician, he is an international expert in the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia, and is a freelance researcher in London.