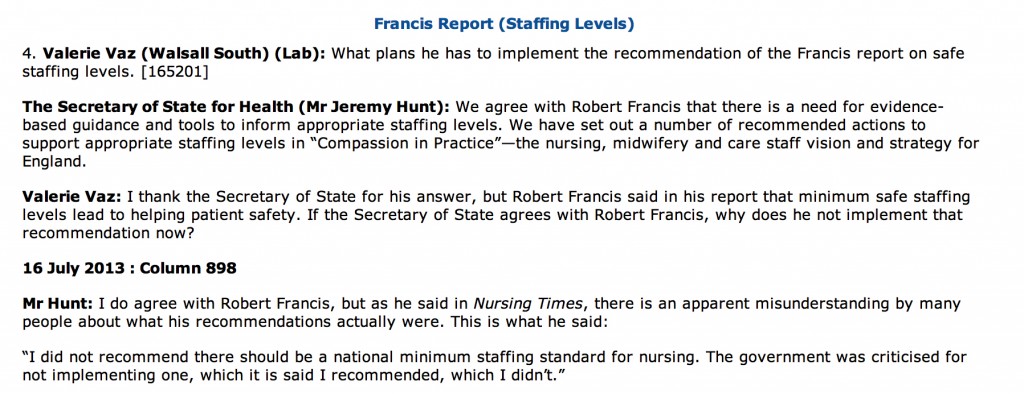

Despite clear differences in opinion about what has happened in the past, patient groups, Andy Burnham, Jeremy Hunt, the Unions, bloggers, experts, other patients, whistleblowers, and relatives at face value appear to want the same thing: a safe NHS where you do not go into hospital as a risky event in itself. The issue of safe staffing in nursing has become the totemic pervasive core issue of secondary care safety, and no amount of parliamentary time one suspects will ever do proper justice to it. In reply to a question from Valerie Vaz, who is herself on the Health Select Committee, Jeremy Hunt immediately quoted the Nursing Times and the Francis Report (from Tuesday 16 July 2013):

The aim of the Nursing Times’ Speak Out Safely (SOS) campaign is to help bring about an NHS that is not only honest and transparent but also actively encourages staff to raise the alarm and protects them when they do so.

They want:

- The government to introduce a statutory duty of candour compelling health professionals and managers to be open about care failings

- Trusts to add specific protection for staff raising concerns to their whistleblowing policies

- The government to undertake a wholesale review of the Public Interest Disclosure Act, to ensure whistleblowers are fully protected.

A very impressive gamut of organisations have supported the “Nursing Times Speak Out Safely” campaign, including Cure the NHS, the Florence Nightingale Foundation, the Foundation of Nursing Studies, Mencap Whistleblowing Hotline, Patients First, Public Concern at Work, Queen’s Nursing Institute, Royal College of Nursing, Unite (including the Community Practitioners and Health Visitors Association and Mental Health Nurses Association), and WeNurses. Also, for example, according to the Royal College of Midwives, maternity staff must be able to publicly raise concerns about the safety of mother and babies without fear of reprisal from their employers, according to the Royal College of Midwives. This college has been the latest organisation to support the Speak Out Safely campaign. They are calling for the creation of an open and transparent NHS, where staff can raise concerns knowing they will be handled appropriately and without fear of bullying.

The pledge of the Speak Out Safely campaign of Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust is a pretty typical example of the way in which this campaign has successfully reached out to all people who have the focused aspiration of patient safety.

“This trust supports the Nursing Times Speak Out Safely campaign. This means we encourage any staff member who has a genuine patient safety concern to raise this within the organisation at the earliest opportunity.

Patient safety is our prime concern and our staff are often best placed to identify where care may be falling below the standard our patients deserve. In order to ensure our high standards continue to be met, we want every member of our staff to feel able to raise concerns with their line manager, or another member of the management team. We want everyone in the organisation to feel able to highlight wrongdoing or poor practice when they see it and confident that their concerns will be addressed in a constructive way.

We promise that where staff identify a genuine patient safety concern, we shall not treat them with prejudice and they will not suffer any detriment to their career. Instead, we will support them, fully investigate and, if appropriate, act on their concern. We will also give them feedback about how we have responded to the issue they have raised, as soon as possible.

It is not disloyal to colleagues to raise concerns; it is a duty to our patients. Misconduct or malpractice should never be tolerated, while mistakes and poor practice may reveal a colleague needs more training or support, or that we need to change systems or processes. Your concerns will be dealt with in an open and supportive manner because we rely on you to ensure we deliver a safe service and ensure patient safety is not put at risk. We also want this organisation to have the confidence to admit to mistakes and to use them as learning opportunities.

Whether you are a permanent employee, an agency or temporary staff member, or a volunteer, please speak up when you feel something is wrong. We want you to be able to Speak Out Safely.”

The Keogh report is in its entirety is an apolitical report, and is very constructive. It identifies problems which Keogh’s team (which currently consists of some brilliantly talented Clinical Fellows) have a realistic chance of tackling. Despite criticisms that Hunt has turned up the ‘political heat’ on this issue, there is a feeling that Labour and Andy Burnham MP should either ‘put up or shut up’. If you park aside the mudslinging over the 13,000 ‘needless deaths’ from irresponsible journalism from parts of the media, the current Department of Health has surely begrudgingly have to be given some credit for instigating appropriate responses such as the Keogh review, and a Chief Inspector of Hospitals. There has been a real effort to clear up the methodology of estimating mortality figures, and while methodology issues will persist, an approach which fully involves and acknowledges the views of patients, whatever their political affiliations, is the only way forward.

As an immediate response to the terms of reference to protect patients from harm, Keogh thrust high up the importance of instigating changes to staffing levels and deployment; and dealing with backlogs of complaints from patients. Keogh identified a basic deficiency in effective performance management in the 14 NHS Trusts under investigation, and these basic performance management techniques are now commonplace in successful corporates. These constitute understanding issues around the trust’s workforce and its strategy to deal with issues within the workforce (for instance staffing ratios, sickness rates, use of agency staff, appraisal rates and current vacancies) as well as listening to the views of staff; Keogh laid down a number of “ambitions”. In ambition 6, Keogh argued that nurse staffing levels and skill mix should appropriately reflect the caseload and the severity of illness of the patients they are caring for and be transparently reported by trust boards.

The review teams especially found a recurrent theme of inadequate numbers of nursing staff in a number of ward areas, particularly out of hours – at night and at the weekend. This was compounded by an over-reliance on unregistered staff and temporary staff, with restrictions often in place on the clinical tasks temporary staff could undertake. There were particular issues with poor staffing levels on night shifts and at weekends. There were also problems in some hospitals associated with extensive use of locum cover for doctors.This observation is interesting as at the end of day an over-reliance on agency staff in both private and public sector from a performance management perspective will guarantee the NHS not getting the best out of its staff, and will further impede hospital CEOs from meeting their ‘efficiency targets’. As set out in the “Compassion in Practice”, Directors of Nursing in NHS organisations should use evidence-based tools to determine appropriate staffing levels for all clinical areas on a shift-by-shift basis. This means that a statutory minimum may be the inappropriate sledgehammer for an important nut. It is proposed that boards should sign off and publish evidence-based staffing levels at least every six months, providing assurance about the impact on quality of care and patient experience. The National Quality Board will shortly publish a ‘How to’ guide on getting staffing right for nursing. Whilst it is easy to argue against a national minimum number for nurses, as one can easily argue that it might encourage a race-to-the-bottom with managers gaming the system such that they only provide the minimum to run their Trust, most people, irrespective of the strong-held and important views of professionals within the nursing profession, believe that running a service with too few nurses is simply too risk for the remaining nurses. At times of high demand, Trusts need to be adaptable and flexible enough to cope, as anyone who has been involved in acute care in national emergencies has been involved (“critical incidents”).

Staffing was a recurrent pathology in the 14 Trusts under investigation. In Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, it was argued that the Trust needs to review current staffing levels for nursing and medical staff. In Buckinghamshire NHS Trust, the panel had a concern over staffing levels of senior grades, in particular out of hours. In Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust, it was found that staffing in some high risk wards needs urgent review. For the Dudley Group NHS Foundation Trust, inadequate qualified nurse staffing levels were identified on some wards, including two large wards which needed to be reviewed in light of concerns raised by the panel. For North Lincolnshire and Goole NHS Foundation Trust, there were concerns over the staffing of key elements of acute care, including recruitment of staff and maintenance of adequate staffing levels and skill mix on the wards. In North Cumbria University Hospital NHS Trust, inadequate staffing levels was identified, as well as an over-reliance on locum cover in some areas of the Trust.

For East Lancashire NHS Trust, the review team considered that staffing levels were low for medical and nursing staff when compared to national standards. Registrar cover and medical staffing in the emergency department was considered poor (this is medical ‘code’ for an overreliance on juniors at Foundation level), and levels of midwifery staff were considered poor too. Certain clinical concerns raised by staff have not been addressed, including known high mortality at the weekends. Whilst some of these actions will take longer to address entirely, assurance in respect of patient flows in A&E and concerns over staffing in the midwifery unit had already been sought by the CQC. For Medway NHS Foundation Trust, a top priority was made of teviewing staffing and skill mix to ensure safe care and improve patient experience, emphasising yet again that there might be false security to be derived from just looking at the overall number. For Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, significant concerns around staffing levels at both King’s Mill Hospital and Newark Hospital and around the nursing skill mix, with trained to untrained nurse ratios considered low, at 50:50 on the general wards. Finally, for United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust, inadequate staffing levels and poor workforce planning particularly out of hours were discovered; concern over the low level of registered nursing staff on shifts in some wards during the unnannounced visit out of hours was escalated to CQC. Further investigation is underway.

This is a matter for all the political parties to get to the bottom of urgently. Party affiliations and tribal politics threaten real substantial progress in this area for all those who work in this area. This is not the time for energised disputes about political leadership in organisations. This is most certainly a time for action. Both the Francis report into the failures of care at Mid Staffs, and The Keogh Review into high hospital mortality rates, highlight how important the right skills mix and sufficient numbers of staff are to providing top quality care. Having the right staff cover is increasingly important out of hours – at evenings and weekends. With all political parties urging a need to work ‘harder and smarter’, or generally under the rubric of working more ‘efficiently’, this is a harsh climate, due to shrinking budgets as the cost of healthcare rises, and because of demands for £20 billion of so-called efficiency savings. Of course, the public are not involved in a genuine public debate at the moment which does not depict the ageing population as a budgetary ‘burden’ on the society, instead pumping in a carefree way billions into the HS2 project with its unclear business case. Billions more have been wasted on a chaotic, unnecessary top down reorganisation of the NHS; the National Audit Office has latterly criticised for the Government for going ‘over-budget’ on these bureaucratic reforms. Frontline staff are obviously rightly angry that this is money that they feel this is money that could and should have gone towards actually caring for patients.

The tragedy is that it really feels as if the NHS has never known, or unlearnt at great speed, basic performance management. One can argue until the cows come home how in this managerial-heavy approach to the NHS such management is extremely poorly done in such a way the CIPD would feel ashamed at possibly. The NHS will deserve to have problems in recruiting the best managers for the NHS so long as the climate of performance management, perhaps affected by an obsession for targets, remains deeply unappealing. It is recognised that good performance management helps everyone in the organisation to know hat the organisation is trying to achieve, their role in helping the business achieve its goals, the skill and competencies they need to fulfil; their role, the standards of performance required, how they can develop their performance and contribute to development of the organisation, how they are doing, and when there are performance problems and what to do about them. The general consensus is that, if employees are engaged in their work they are more likely to be doing their best for the organisation. An engaged employee is someone who:

The actual reality is that currently spending pressures mean that many health workers, sadly, are losing their jobs. Financial pressures are building up in the NHS just as the demand for healthcare and its cost is rising – trusts are being asked to make unconscionable savings. Trusts such as Barts Healthcare are in severe trouble, and the contribution of the failed policy of PFI is a massive scandal in itself. This perfect storm will hit standards of patient care hard, and is the direct consequences of decisions made by various recent governments – not by hardworking NHS staff. The only thing which is set up to work in the Act, apart from outsourcing (section 75) and raising massively the private cap (section 164(1)(2A)) of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 is the legal precision of the various failure or insolvency regimes. In any other sector, this would fall under wrongful or fraudulent trading. Except, it’s the NHS. It does economic activity in a very special way. As the shift in economic and political power shifts from a state well-funded comprehensive healthcare system to a fragmented disorganised piecemeal private integrated system in the next few decades, patient safety must take priority even if not a top priority seemingly in business plans. Initiatives such as the Nursing Times ‘Speak out Safely’ campaign is one of those vital ‘checks and balances’ to ensure that the NHS is working with and for patients and not against them. This means the NHS valuing staff as a top priority, as social capital is the most important thing in any organisation.

Pingback: If Labour 'crushed the culture of care', what do patient groups actually want to do about patient safety? - Socialist Health Association()

Pingback: To deny the need for safe nursing staffing levels is to defend the indefensible - Socialist Health Association()

Pingback: Matthew d’Ancona on the formation of the Coalition: they were the future once()