“Dementia Friends” is an initiative from the Alzheimer’s Society and Public Health England. In this series of blogpost, I take an independent look at each of the five core messages of “Dementia Friends” and I try to explain why they are extremely important for raising public awareness of the dementias.

That ‘Dementia is caused by diseases of the brain’ may seem like a pretty innocuous statement.

There have been numerous attempts at looking at the numbers of the different causes of dementia, varying in overall success over the years.

One study “Prevalence of dementia subtypes: A 30-year retrospective survey of neuropathological reports” came from Hans Brunnström, Lars Gustafson, Ulla Passant and Elisabet Englundemail in 2008.

The authors investigated the distribution of neuropathologically defined dementia subtypes among individuals with dementia disorder.

The neuropathological reports were studied on all patients (n?=?524; 55.3% females; median age 80, range 39–102 years) with clinically diagnosed dementia disorder who underwent complete post mortem examination including neuropathological examination within the Department of Pathology at the University Hospital in Lund, Sweden, during the years 1974–2004.

The neuropathological diagnosis was Alzheimer’s disease in 42.0% of the cases, vascular dementia in 23.7%, dementia of combined Alzheimer and vascular pathology in 21.6%, and frontotemporal dementia in 4.0% of the patients.

Different types of dementia (and factsheets about them) are summarised in this page from the Alzheimer’s Society.

Part of the problems with the statement comes from the definition of ‘dementia’.

For example, a WHO definition is provided thus:

“Dementia is a syndrome – usually of a chronic or progressive nature – in which there is deterioration in cognitive function (i.e. the ability to process thought) beyond what might be expected from normal ageing. It affects memory, thinking, orientation, comprehension, calculation, learning capacity, language, and judgement. Consciousness is not affected. The impairment in cognitive function is commonly accompanied, and occasionally preceded, by deterioration in emotional control, social behaviour, or motivation.”

However academics and practitioners over the years have squabbled over the nuances of the definition. Should the definition compulsorily include memory in the early stages? Most people I think would agree ‘no’, if only because of the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia where individuals present with an insidious progressive change in behaviour and personality in the early stages can report no changes in their memory. And can it be reversible?

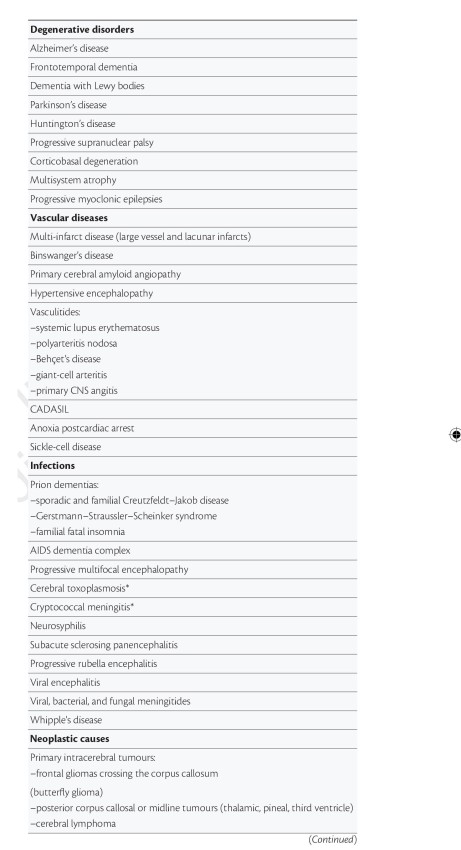

This is Prof John Hodges’ list of the dementias presented in the current Oxford Textbook of Medicine, which is helpful.

But problems in metabolism from the rest of the body can cause problems in brain function. The list is a long one, and an introduction to this topic here.

And antibodies raised in cancers which haven’t revealed themselves yet can cause a dementia-like picture.

Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis (PLE) is a rare disorder characterized by personality changes, irritability, depression, seizures, memory loss and sometimes dementia.

This diagnosis is difficult because clinical markers are often lacking, and symptoms usually precede the diagnosis of cancer or mimic other complications.

A range of tumours outside of the brain can be implicated in this complicated conditions, including oesophagus, lung, bladder, colon, lung, thymus and breast.

This is for example a helpful summary table from Gultekin and colleagues in Brain. 2000 Jul;123 ( Pt 7):1481-94.

They can be associated with markers in the fluid surrounding the spinal cord, and in magnetic resonance imaging of the brain. But to call them “diseases of the brain” would be a massive over-simplification?

And there might not be a biological disease at all causing profound symptoms.

McKay and Kopelman’s article “Psychogenic amnesia: when memory complaints are medically unexplained” in Advances in psychiatric treatment (2009) [vol. 15, 152–158 doi: 10.1192/apt.bp.105.001586] is an extremely useful introduction.

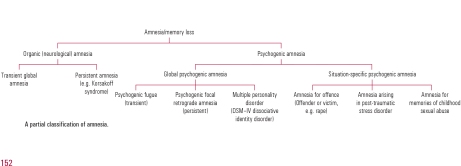

Amnesia is a particular cognitive problem. Amnesia has been defined as ‘an abnormal mental state in which memory and learning are affected out of all proportion to other cognitive functions in an otherwise alert and responsive patient’ (Victor 1971).

According to them, “A number of terms have been used to describe medically unexplained amnesia, including ‘hysterical’, ‘psychogenic’, ‘dissociative’ and ‘functional’. Each requires the exclusion of an underlying neurological cause and the identification of a precipitating stress that has resulted in amnesia. Unfortunately, the presence of amnesia may make it difficult to identify the stress until either informants have come forward or the amnesia itself has resolved”.

They helpfully provide this scheme for looking at the causes.

Hans J. Markowitsch looked at “Psychogenic amnesia” in an extremely useful article in NeuroImage 20 (2003) S132–S138.

Markowitsch, a world leader in memory, kicked off with the realisation that sometimes a disease of the brain, in terms of an identifiable pathology, often could not be located for quite profound symptoms.

“Commonly, memory disturbances are related to organic brain damage. Nevertheless, especially the old psychiatric literature provides numerous examples of patients with selective amnesia due to what at that time was preferentially named hysteria and which implied that both environmental circumstances and personality traits influence bodily and brain states to a considerable degree. Awareness of the existence of relations between cognition, soma, and psyche has increased especially in recent times

and has created the research branch named cognitive neuropsychiatry.”

Mizutani and colleagues (2014) have indeed reported a case which could to all intents-and-purposes have been caused by a disease of the brain.

Its cause is an overactive thyroid, a gland in the neck.

“We report the case of a 20-year-old Japanese woman with no psychiatric history with apparent dissociativesymptoms. These consisted of amnesia for episodes of shoplifting behaviors and a suicide attempt, developing together with an exacerbation of Graves’ hyperthyroidism. Patients with Graves’ disease frequently manifest various psychiatric disorders; however, very few reports have described dissociative disorder due to this disease. Along with other possible causes, for example, encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroid disease, clinicians should be aware of this possibility.”

Dissociative disorders can take many forms – see this factsheet from Mind.

It is thought that dissociative amnesia is amnesia caused by trauma or stress, resulting in an inability to recall important personal information.

Therefore ‘Dementia is caused by diseases of the brain’ is not in fact an innocuous statement. But for the purposes of “Dementia Friends”, it is.

Further references

Victor M, Adams RD, Collins GH (1971) The Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome. F.A. Davis.

Mizutani K, Nishimura K, Ichihara A, Ishigooka J. Dissociative disorder due to Graves’ hyperthyroidism: a case report. (2014) Gen Hosp Psychiatry, Mar 19. pii: S0163-8343(14)00073-5. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.03.010.

Pingback: The five key messages of ‘Dementia Friends’ | Living well with dementia()