Home » society

Personal images of Shibley Rahman around London

I love London, which is the city in which I live.

Here are some personal pictures of me in London, taken very recently. They are not also available in my Gallery, but I should love you to look at my Gallery.

Christina Zaba's Top 15 writers

You’ve probably all seen the game on Facebook. Christina Zaba, whose journalism first came to my attention through her writings on data protection (see example here), took part in this game.

The game goes as follows:

Here’s a nice game if you’re inclined to play for a few moments. Don’t take too long to think about it. List fifteen authors (poets included) who’ve influenced you and who will always remain with you. List the first fifteen that spring to mind in no more than fifteen minutes. Tag at least fifteen friends, including me. This is the first facebook “game” I’ve taken part in, because I’m really curious to see which authors people consider to have been personally important to them. (To do this, go to your Notes tab on your profile page, paste these rules in a new note, cast your fifteen picks, and tag people under Tags below the note.) Thanks for playing.

William Shakespeare

Emily Bronte

Scott Fitzgerald

Joseph Conrad

Anna Sewell

TS Eliot

Clarissa Pinkola Estes

JRR Tolkien

Thomas Malory

John Donne

William Blake

Alan Garner

Emily Dickinson

Germaine Greer

William Golding

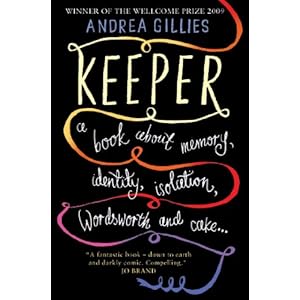

Dr Shibley Rahman : review of "Keeper" by Andrea Gillies

Andrea Gillies argues that dementia is ill-understood and remains so stigmatized that the government fails to treat it with the same urgency as other illnesses such as cancer. The historical lack of prioritization of dementia in the UK is indeed based on substantial fact and is utterly surprising, but it seems that all political parties have now pledged to remedy this despite the necessary age of financial austerity.

In her book ‘Keeper’, Andrea Gillies describes moving but unsentimental terms the day-to-day experience of caring for Nancy, her mother-in-law affected by Alzheimer’s disease. I felt the book was outstanding, explaining how a person is changed because of a real underlying disease. This book is the only one I know of which charts brilliantly a person’s cognition, personality and behaviour extremely accurately, and which is entirely in keeping of decades of research of the progression of the disease in cognitive neuroscience.

The Wellcome Trust and George Orwell prizes – richly deserved

The book has already won two prestigious awards – the Wellcome Prize, in recognition of its dispassionate analysis of the effects the disease has on the brain, and the George Orwell Prize, recognizing the author’s anger at a medical and social care system that is failing to support sufferers and their carers. The Orwell Prize is the pre-eminent British prize for political writing, and previous winners include Raja Shehadeh and Peter Hennessy.I think that the anger should be viewed in terms of improving dementia care, something which I feel passionate about, rather than any criticisms of the system. Confidence will only be undermined unless we address coherently these weaknesses.

On the Orwell panel, English PEN director Jonathan Heawood, writer Francine Stock and Andrew Holgate, literary editor of The Sunday Times, provided that Keeper is a ‘startlingly honest and vivid‘ work which goes beyond being just a memoir to examine issues such as identity and memory. ‘[Gillies] argues powerfully for change in the way we deal with age and senility, a looming political issue for the 21st century,’ the panel also commented.

While some Alzheimer’s books, such as John Bayley’s “Elegy for Iris,” are enmeshed with memories of the person before illness, Andrew Gillies intersperses her narrative with smart, very accessible narratives on the history and science of the Alzheimer’s syndrome.

Overview

At the outset of ‘Keeper’, Nancy wakes “to find that she has aged 50 years overnight, that her parents have disappeared, that she does’t know the woman in the mirror, nor the people who claim to be her husband and children, and has never seen the series of rooms and furnishings that everyone around her claims insistently is her home.”

The transition from full cognition to the cognitive and the neuropsychiatric deficits found in Alzheimer’s disease is likened to stepping through “Alice’s looking glass”.

Andrea Gillies explains that the most distressing period is when you are moving from one side to the other:

“She had one foot through the looking glass and she couldn’t make those two worlds – dementia reality, and normal life – gel at all …It was really quite science fiction in a way. Complete strangers coming into the house and saying ‘How are you today? Shall we go and have a walk?’ Obviously your reaction is going to be ‘What are you talking about? I’ve no idea who you are.’ She would awake in the morning not knowing who the man in the next bed was and she was afraid. Strangers would come into her bedroom and hand her clothes she had never seen before.”

Andrea Gillies and her husband, facing his parents’ declining health, purchased a spacious Victorian home on the Scottish coast large enough for all of them: Andrea Gillies, her husband, their three children and Nancy and her husband, Morris. The property had several acres; they kept dogs, a large garden, chickens and horses. From inside the house, they could see the rocky coast and windblown sea. ??This book is a journal of life in this wild location, in which Andrea Gillies tracks Nancy’s progression through a powerfull disease.

Memory

Early on, Nancy could express herself, but she needed help dressing, a sign of the disease’s grip. In the new house her difficulties increased: her short-term memory was degraded so that she had a hard time recognizing where she was. Indeed, problems in spatial memory is supposed to be a recognized hallmark early symptom of the disease, as the disease is centred around the medial temporal lobe initially (a part of the brain near the ear). The pattern of memory deficit is exactly as described in the seminal work of Ribot (1881), where memory for old events is relevantly preserved, compared to the encoding of new memories which is relatively impaired. “She couldn’t map her new home. Every morning she woke up thinking she had just arrived and she didn’t know where the kettle was or how to get to the bathroom. This made her angry and afraid,” according to Gillies.

In the book, it is also described that doctors initially prescribed Nancy drugs designed to stay the loss of memory, but it is not clear that these had much effect. The evidence has been that the cognitive effects of a popular group of dementia symptom-improving drugs for memory and attention, the cholinesterase inhibitors, have overall been modest, but the effects have been variable amongst recipients (with some patients, and their immediates, noting remarkable improvements).

The environment

Personally, I found the account of the enormous significance of the environment to patients with dementia incredibly powerful. the resemblance of Nancy’s new home to her childhood home provided, instead of comfort, confusion: she sometimes insisted her long-dead father was nearby. It swiftly becomes clear that they cannot look after themselves in their new home, so Gillies and her husband decide to sell up their own family home and buy a big Victorian house on a remote Scottish peninsula, moving their 10-old-year son, Jack, and his two teenage sisters into new schools and creating two separate establishments in one home, connected by a communal kitchen. The role of empowering patients with their environment instead of being unsettling can potentially be utilized to improve the quality-of-life of patients with their dementia, but this work has yet to make the huge advances it is worthy of in my opinion. Amazing progress has already been made, on a positive note.

Personality and behaviour

What makes this book special is that although it is very much an exploration of episodic memory, its loss and the subsequent erosion of personality, it is also a very useful chronicle of the effects that the onset of Alzheimer’s disease can unleashe on the extended family. It is also a chronicle of Gillies’ own unravelling, as the exhausting, realities of a carer’s role overwhelm her. Most powerful, however, is Nancy’s own voice, carefully recorded by Gillies in nightly diary entries, a voice that is at times cantankerous, bewildered, but defiant. Reading these monologues, we get very close to understanding what it feels like to experience this illness.

As the disease progresses through the brain, other areas, controlling personality and behaviour in the frontal lobes, can change a person in dementia. Some patients are mystically described by immediates as ‘changing for the better’, but Gillies is unable to give such a view of Nancy. Nancy deteriorates from a somewhat benignly forgetful doting grandmother to a raging harpy, who slaps her granddaughters, calls her beloved grandson variously a bastard, arsehole and bitch, cannot remember how to use cutlery, prefers not to wash, tucks used bits of loo paper up her sleeve, squats on the floor to pee and hides her own turds behind paperbacks in the bookshelves (“the kind of discovery that’s unexpected late at night when you’re looking for something to read”). For me, the accounts of late Alzheimer’s disease were very reminiscent of what happens, in terms of profound behavioural and personality changes, in early behavioural frontal variant frontotemporal dementia. On one occasion recounted in the book, Nancy surprises Australian guests over breakfast when she marches through the dining room wearing nothing more than a large pair of lilac briefs; they are too polite to complain.) The transformation of her mother-in-law’s personality sets Gillies on an investigation into the way the brain controls personality, concluding that identity is biological. “Selfhood isn’t something separate from your biological self,” she writes. “The brain is where your self is made.”

Reviews

“Andrea Gillies’s account of living with Alzheimer’s is the perfect fusion of narrative with enough memorable science not to choke you. It’s a fantastic book – down to earth and darkly comic in places. The judges found it compelling.” Jo Brand, Chair of the judges of the Wellcome Prize, 2009

“A wonderful book ¬– honest, upsetting, tender, sometimes angry, often funny – which takes us on a journey into dementia and explores what it means to be human.” Deborah Moggach

“Terrific, terrifying, absolutely powerful in every choice of word, every sentence… completely unflinching” Quentin Cooper

“This is one of the most moving and important books that I have read on Alzheimer’s.” John Bayley

“Thoughtful, informative and true… a very good, very necessary book.” Sir Richard Eyre, Patron of the Alzheimer’s Research Trust

“Andrea Gillies is a brilliant prose stylist with a poet’s facility for metaphor and a brave wit born of exasperation and sadness.” Professor Raymond Tallis

You can purchase “Keeper: a book about memory, identity, isolation, Wordsworth and cake…” by Andrea Gillies (www.shortbooks.co.uk) here.

Dr Shibley Rahman trained in cognitive neurology at Cambridge and in London. Although he is not a practising physician, he is an international expert in the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia, and is a freelance researcher in London.

Robin Lane Fox's badger

Firstly, may I recommend profusely Robin Lane Fox’s brilliant “Thoughtful Gardening“, subtitled, “Great plants, great gardens, great gardeners“.

The book is fascinating to anyone interested in gardens, but also I reckon the book will be of enormous interest to people with more than a mere passing interest in the classics, politics and psychopharmacology.

Why psychopharmacology?

Suddenly, out of the blue, on page 120, Lane Fox provides an account of his “badger experiment”.

“Prozac is supposed to cure gloom and isolation, especially as the years pass. If an ageing badger is socially miserable, why not cheer him up? At dead of night, I did it. I crushed Prozac in the food mixer and spooned into lumps of crushed peanut butter which fellow sufferers tell me is the supreme badger-attractor. I put sixteen heaps of the mixture at intervals around the lawn. The next morning they were all gone. I feel half ashamed and half proud about what happened next. Two days later I returned late at night from work and, with due astonishment, found a badger trotting down the road off which my drive runs. I caught him in the headlights and, obligingly, he swung right up my drive. How fast can a badger run on Prozac?“

I would humbly submit that there are two very interesting observations to be made from this for any human psychopharmacologist. Firstly, it can be assumed that fluoxetine, a drug that boosts serotonin (a chemical in the brain), is postulated to have the same mode of action in the badger as in the human and other animals. This, one assumes, is through being a selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor. The second element of this first observation is the speed with which the prozac has a possible effect in the badger. Experiments from rats suggest that fluoxetine can have had an almost instantaneous effect in the rat, which is rather at odds to the onset of its antidepressant effects in human (typically 4-6 weeks). Secondly, why exactly was the badger rushing out in front of a car’s headlights? One hopes that it was merely a lifting of the badger’s mood. More sinister is the hypothesized effect of this class in drugs in actually promoting suicidal behaviour, which remains an extremely controversial area of neuroscience. I am not saying for one moment the pellets caused this badger to behave as it did, please note.

Book: Robin Lane Fox, Thoughtful Gardening: Great Plants, Great Gardens, Great Gardeners

Available on the UK Amazon here.

Dr Shibley Rahman is a non-practising academic, research physician and research lawyer by training.

Queen’s Scholar, BA (1st.), MA, MB, BChir, PhD, MRCP(UK), LLB(Hons.), FRSA

Director of Law and Medicine Limited

Member of the Fabian Society and Associate of the Institute of Directors