Home » Regulation (Page 2)

A ‘paradox of regulation’ in the NHS has opened the neoliberal floodgates

At 493 pages, the ‘Health and Social Care Act’ is a massive piece of legislation. Writing a blogpost on it would be like trying to summarise the contents of ‘War and Peace’ in a single tweet. From that perspective, it might seem as if the NHS is over-regulated, and certainly the number of guidelines and policies relating to the NHS has exploded. The Act has no provisions on patient safety, apart from the abolition of the “National Patient Safety Agency”, and yet Monitor is expected to publish a huge armoury of regulation of ‘competitive activity’ in the market. The full-frontal marketisation, together with outsourcing and privatisation of the NHS, is considered totally unacceptable to many reasonable onlookers, especially socialists. Market failure is a very important concept in economics, on the other hand. Market failure is a concept within economic theory describing when the allocation of goods and services by a free market is not efficient. That is, there exists another conceivable outcome where a market participant may be made better-off without making someone else worse-off. Market failures can be viewed as scenarios where individuals’ pursuit of pure self-interest leads to results that are not efficient – that can be improved upon from the societal point-of-view. The first known use of the term by economists was in 1958, but the concept has been traced back to the Victorian philosopher Henry Sidgwick. The general consensus, now, is not that there is a desperate drive for yet ‘more regulation’ at any cost, but there is a need for a higher standard of effective regulation in the NHS, to which not only top CEOs in NHS management can have full access. This is particularly poignant since the volume of budgeted NHS litigation claims has in fact exploded in recent years.

There is an ideological divide between those on the left-wing and those on the right-wing. The Conservatives promoted themselves on ‘light touch regulation’ at roughly the same time as the Financial Services and Markets Bill was going through parliament. There are two crucial issues now for the adequate regulation of the NHS. Firstly, all parties have a concern in patient safety. The previous failures of the Health Service Ombudsman’s office and that of CQC could be, and even now possibly, be pinned down directly on a lack of sufficient resources needed for them to fulfil their functions, and existing staff there would prefer not to amplify any suggestion that they are failing patients. Neoliberals also have an interest in patient safety, as failures in patient safety threaten competitive advantage, ultimately the profitability of private healthcare companies. Secondly, the failure of adequate market regulation in the water industry (and indeed the privatised utilities) still remains powerfully sobering for any ‘users’ of the National Health Service, a group within the general public formerly known as ‘patients’.

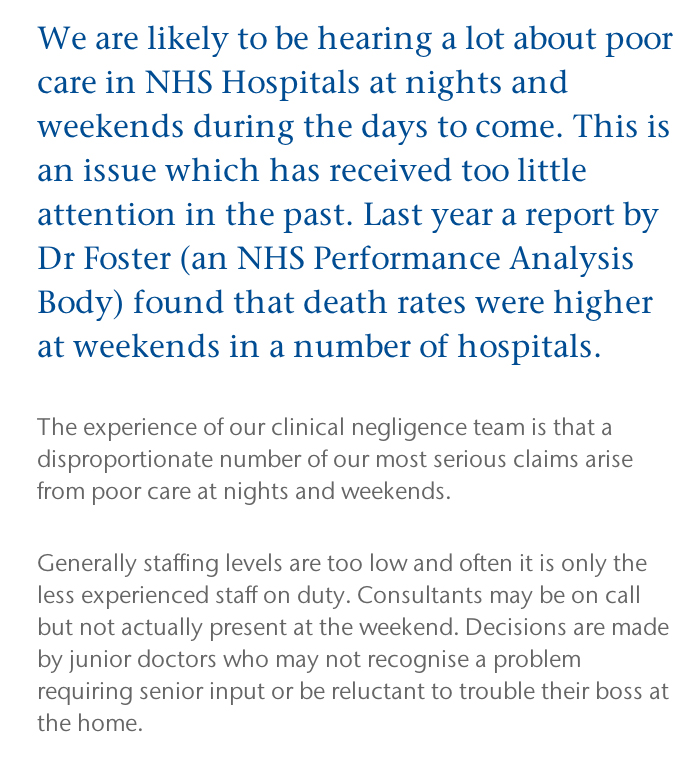

Employment is the first clear example of the ‘law in action’ in the NHS. The NHS, by its own admission, has decided to use compromise and confidentiality agreements in settlement with outgoing employees to prevent them pursuing unfair dismissal claims as is their statutory right. When it comes to a minimum staffing level, the usual riposte from the Right is that the complete answer involves ‘the staffing mix’. However, this is disingeniously to divert from the issue that there is an unsafe staffing level. Despite the fierce debates about the use and statistical reliably of hospital standardised mortality ratios (HMSRs), the clear evidence is that unsafe doctors:bed ratios can shove up the HSMR for weekends both in this jurisdiction and abroad (Dr Foster report 2010-2011, Prof Brian Jarman (personal communication by twitter.)) While the Left (and the Unions particularly) see the minimum staffing levels of nurses as ensuring a safe minimum standard for hospital safety, the Right (and neoliberals) invariably see the safe minimum staffing level as part of ‘the race to the bottom’ to maximise shareholder profitability. Staffing remains the number one issue where more effective regulation in the NHS could make a massive impact on patient safety, and indeed it is likely that this will be addressed as well as the legal duty of candour for hospitals, in Don Berwick’s wideranging report due out tomorrow.

The turbo-charged implementation of the economic market, rejected by true socialists, presents formidable problems for the regulation of the NHS. Traumatic lessons from other sectors, especially the privatised utilities, are particularly helpful here. There are currently twenty one private water companies operating in England, answerable to their shareholders. They are overseen by economic regulator OFWAT. Before 1989, water supply in England and Wales had been in the hands of 10 public regional water authorities, which were then sold off. They are private companies, many are owned by banks, private equity firms or foreign investment funds, like the main supermarkets.Thames Water, for instance, has been owned by Kemble Water Holdings – an investment consortium led by Australian banking and finance group Macquarie, with recent shareholdings taken by the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority and the China Investment Corporation. This democratic deficit of course makes many people angry, whereas the Unions have been the target of malicious smears from virtually all sectors of the media. Similarly, when Cheung Kong Infrastructure was buying Northumbria Water at the end of 2011, it sold Cambridge Water to South Staffordshire Water. South Staffordshire is wholly owned by the US based Alinda Infrastructure Fund.

OFWAT calculates the average water and sewerage bill in England and Wales at £340 for 2011-12, compared to £236 when water was privatised in 1989-90. The Health and Social Care Act and the regulations for implementing it change the nature of the NHS to allocate NHS resources into the private sector, to maximise profitability for shareholders. Private competitive tendering as the default option has seen major contracts being awarded to private sector corporates. The tragedy of this is that some private providers have an atrocious performance record in outsourcing, but because they are able to make slick bids appear to be implementing a ‘winning formula‘ in rent seeking behaviour from the current neoliberal Coalition. Priorities change from patient care to ensuring corporate rights, from spending directly on health care to investor dividends. The UK NHS becomes much more like the corporate-benefit US health care system which has very high spending while many people have no health care.

Any Qualified Provider is a procurement model that CCGs can use to develop a register of providers accredited to deliver a range of specified services within a community setting. The model aims to reduce bureaucracy and barriers to entry for potential providers. The US/EU free trade agreement has been launched, formally called the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP). When TTIP negotiations are completed, unless the neoliberal Coalition manage to negotiate successfully an exemption for the NHS, corporations will have the right to sue the UK government for any attempts at ‘reversals’ that limit future corporate profits. In terms of “ownership”, most of our power generating companies, our airports and ports, our water companies, many of our rail franchises and our chemical, engineering and electronic companies, our merchant banks, an iconic chocolate company – Cadbury, our heavily subsidised wind farms, a vast amount of expensive housing and many, many other assets, all disappeared into foreign ownership. No mainstream party appears to be making any progress in this. Debbie Abrahams, Labour MP for Oldham East and Saddleworth, as a lone voice almost, has lodged a question from David Cameron regarding what exemption (if any) has been negotiated (recorded in Hansard here), and it turns out that Debbie Abrahams has now received a rather unclear reply.

In the EU, there are concerns that liberalising public procurement markets, combined with measures to protect foreign investors from government action, could constrain the power of national governments to decide how public services are provided. Concerns about the status and future of the NHS have been raised in the UK by people from many quarters other than in the Socialist Health Association. In particular, some commentators have claimed that measures to open up the NHS to competition would be made irreversible under the TTIP if its investor protection regime required US companies to be compensated in the event of a change of policy. This is of course a very dangerous situation. The liberalisation of the NHS market through the US-EU would be accelerated through a US-EU Free Trade Agreement. This is something which some corporates have been working very hard on ‘behind the scenes’. To dismiss this issue as scaremongering by the Socialist Health Association, which is supposed to uphold socialist principles and oppose further marketisation and privatisation, would be to turn a blind eye to all the legal evidence and judgments.

The legal arguments against further privatisation of the NHS are overwhelmingly strong, and there is a distinct lack of effective regulation of the NHS currently. Such poor regulation, whilst a boon for profiting private health providers, offends what is actually in the ‘best interests’ of patients.

This should massively concern socialists.

We can’t go on like this.

Where was the Big Society last week in the parliamentary discussion of the Keogh report?

The Big Society was the flagship policy idea of the 2010 UK Conservative Party general election manifesto. It now forms part of the legislative programme of the Conservative through the Liberal Democrat Coalition Agreement. Its stated aim was to create a climate that empowers local people and communities, building a “Big Society” that will take power away from politicians and give it to people.The idea was launched in the 2010 Conservative manifesto and described by The Times as “an impressive attempt to reframe the role of government and unleash entrepreneurial spirit”. The plans include setting up a Big Society Bank and introducing a national citizen service. The stated priorities were to give communities more powers (localism and devolution), encourage people to take an active role in their communities (volunteerism), transfer power from central to local government, support co-ops, mutuals, charities and social enterprises, and publish government data (open/transparent government).

The Big Society remains as vague now, as it did then. Localism has clearly been a frustration of ‘communities taking action’. Both the ‘Save Trafford A&E’ and ‘Save Lewisham A&E’ have been on the receiving end of an argument which urges the need for responsible reconfiguration of NHS services.Whilst campaigners in both situations have urged the need for recognition of their own services, the constant rebuttal has been that in any policy formulation or consultation there are bound to be dissenting views particularly if the sample size of respondents is high. Many people will share the frustration of those who had been encouraged by mechanisms such as the Localism Act (2011), in wider local issues.

There has been a big drive also to encourage ‘social value’ in public services, manifest in the Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012. The fundamental idea behind ‘social value’ is that it is a way of thinking about how scarce resources are allocated and used. It involves looking beyond the price of each individual contract and looking at what the collective benefit to a community is when a public body chooses to award a contract. Social enterprises are businesses that exist primarily for a social or environmental purpose. They use business to tackle social problems, improve people’s life chances, and protect the environment. Healthwatch England has referred to “The NHS Bodies and Local Authorities (Partnership Arrangements, Care Trusts, Public Health and Local Healthwatch) Regulations 2012″.

In relation to the section covering political campaigning, their view is that,

“section 36(2) ensures local Healthwatch has the necessary freedom to undertake campaigning and policy work related to its core activities and believe to do otherwise would be distracting. We do however, appreciate how there could be some confusion due to the nature of the wording in the section.”

Another issue is how failing Trusts have been allow to provide poor care for members of the general public. Accusations have been made of a poor ‘culture of care’, and this issue has become political with accusation-and-counteraccusation. Patient groups are vital in representing the views of patients accurately. I know, because I was resuscitated after a cardiac arrest and successfully kept alive for six weeks in a coma at the Royal Free Hampstead. However, more than a decade ago, I studied my basic medical degree at Cambridge and Ph.D. also in early onset dementia there. The concern is that Trusts are not being altogether transparent in their metrics about care. However, I personally think patient groups to do this responsibly should be free to campaign on behalf of patients for poor care, but without turning the public against all hard-working doctors and nurses. My experience was that junior doctors and nurses feel terrible about episodes of poor care, so they definitely wish to work with the patient groups. This is not at all a ‘them against us’ issue, but the language of ‘service user’ and ‘they’re providing a service we pay for’ have not helped in this narrative, perhaps together with a concept that clinicians ‘carry out orders to maintain managerial targets’. This concept is particularly toxic, as it might appear at first blush consistent with a growing trend towards the deprofessionalisation of medical Doctors and nurses. Patient groups do an extremely worthwhile rôle, and I have the highest regard for them.

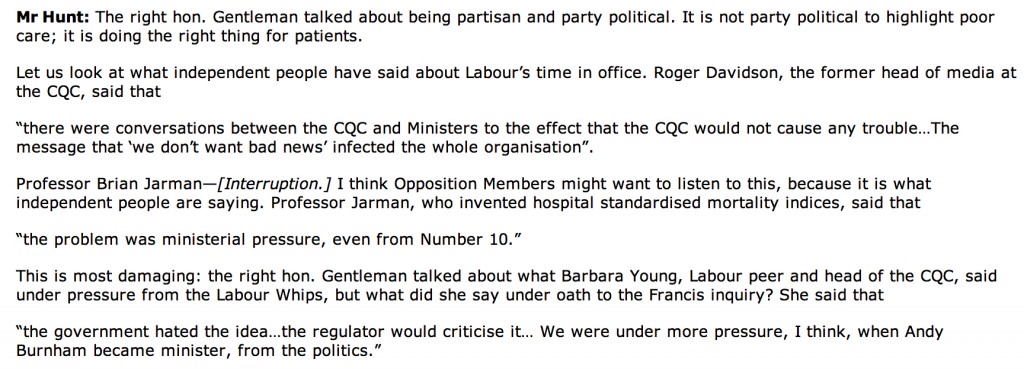

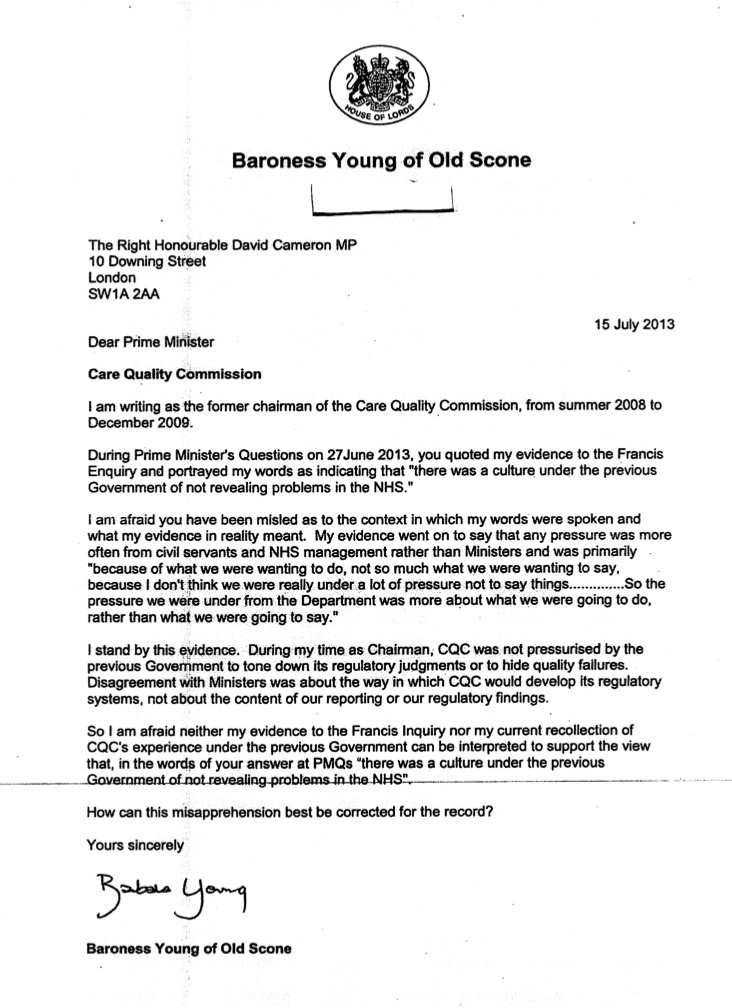

This is why it is all the more important I feel that these issues about the NHS can be held in future in a dignified and balanced manner, without further talk of Hunt ‘politicising the NHS’ or an ‘active smear campaign against Andy Burnham’. Patient groups need to be carefully about their involvement in the media, otherwise they can easily become politicised. The academic issue of whether HSMRs are reliable has become politicised, although the academic debate about HSMR is safely ringfenced in the academic journals such as the British Medical Journal. The limitations of the claims of ‘excess deaths’ or ‘needless deaths’ always needed to be done carefully, and it was left to Sir Bruce Keogh himself and media sources not particularly known for their Conservative loyalty, such as the Guardian or New Statesman, to defuse the panic which had set in following irresponsible reporting of the Keogh mortality report at the weekend.

Political campaigning is defined by the Charity Commission is as follows:

Campaigning: We use this word to refer to awareness-raising and to efforts to educate or involve the public by mobilising their support on a particular issue, or to influence or change public attitudes. We also use it to refer to campaigning activity which aims to ensure that existing laws are observed. We distinguish this from an activity which involves trying to secure support for, or oppose, a change in the law or in the policy or decisions of central government, local authorities or other public bodies, whether in this country or abroad, and which we refer to in this guidance as ‘political activity’.

Further details are given as follows:

“Political activity, as defined in this guidance, must only be undertaken by a charity in the context of supporting the delivery of its charitable purposes. We use this term to refer to activity by a charity which is aimed at securing, or opposing, any change in the law or in the policy or decisions of central government, local authorities or other public bodies, whether in this country or abroad. It includes activity to preserve an existing piece of legislation, where a charity opposes it being repealed or amended.”

It would seem therefore that the definition of ‘political activity’ is not the same as the “rough and tumble” of politics seen in House of Commons debates, nor even on Twitter. However, it is really hard to know what ‘changes in the law’ might follow from Keogh or the Francis Report. This in part, one must to be admitted, needs clear definition what an appropriate ‘outcome’ might be. If the aspiration is “safe staffing”, serious consideration should be put into how enforceable this is, how it could be measured. and what sanctions might follow from an offence regarding it. A clear problem is that stakeholders will always have different views, particularly if there are more of them, and resolving conflicting views is especially difficult. This is all the more significant if you hope a ‘motherhood and mother pie’ approach in keeping with that ‘flagship policy’ of the Big Society. It is clear that some patient groups, indeed the Government, oppose a flat ‘minimum staffing level’ for perfectly rational reasons:

Christina McAnea, UNISON head of health, said this week:

We are pleased that the Keogh Review, as the Francis Report before it, has recognised the relationship between quality care and safe staffing levels. UNISON has been campaigning for safe staffing levels and the right skills mix on wards for many years. This includes in the evenings and at weekends – there is clear evidence that out of hours cover isn’t safe. It is time for the government to start listening and take action by committing to minimum staffing levels. They must also listen to staff and patients who are the best barometer of an organisation.

Spending pressures mean that health workers are losing their jobs. Financial pressures are building up in the NHS just as the demand for healthcare and its cost is rising – trusts are being asked to make obscene savings. Undoubtedly, this will hit standards of patient care hard, and is the direct consequences of decisions made by the government – not by hardworking NHS staff.”

Whilst one clearly not make everyone happy all of the time, it is fortunate that there are so many brilliant stakeholders who ultimately want the best of patients in the NHS. The purpose of the English law is obviously not to get in the way of all the people participating in English health policy at this particularly sensitive time. Politicians can help too by not turning people against other people, and members of the public can help too by not doing the same.

Is it necessary to ‘pierce the corporate veil’ in addressing patient safety in the public interest?

The impact of poor staffing on patient safety in the NHS cannot be underestimated especially now. Paul Sankey, Principal Lawyer (Partner) in Clinical Negligence at the law firm Slater & Gordon LLP, wrote this week as follows:

As hospital services are increasingly outsourced to the private sector, and as NHS Foundation Trusts themselves are financed at a corporate level through mechanisms such as the Private Finance Initiative (PFI), it has become necessary to consider the extent to which such private operations can be scrutinised through freedom of information (FOI) legislation. Generally, private bodies are excluded from FOI across a number of jurisdictions, and there has even be a sectoral approach under scrutiny. It is a well established principle that the company has a separate legal personality from its members. In very limited circumstances, the English courts can ‘pierce the corporate veil’, putting to one side the company’s separate legal personality and holding that its members are subject to the legal consequences of the company’s acts. Obvious examples might include product liability in breast implants (PIP implants), but more subtle is to consider the effect of staffing levels in the operation of private companies or indeed PFI-sourced NHS Foundation Trusts.

As hospital services are increasingly outsourced to the private sector, and as NHS Foundation Trusts themselves are financed at a corporate level through mechanisms such as the Private Finance Initiative (PFI), it has become necessary to consider the extent to which such private operations can be scrutinised through freedom of information (FOI) legislation. Generally, private bodies are excluded from FOI across a number of jurisdictions, and there has even be a sectoral approach under scrutiny. It is a well established principle that the company has a separate legal personality from its members. In very limited circumstances, the English courts can ‘pierce the corporate veil’, putting to one side the company’s separate legal personality and holding that its members are subject to the legal consequences of the company’s acts. Obvious examples might include product liability in breast implants (PIP implants), but more subtle is to consider the effect of staffing levels in the operation of private companies or indeed PFI-sourced NHS Foundation Trusts.

The RCN provide that staffing levels for nursing must be adequate:

“Attention is now focussed more sharply than ever on staffing. Public expectation and the quality agenda demand that the disastrous effects of short staffing witnessed at NHS hospitals such as Mid Staffordshire should not be allowed to happen again. Time and again inadequate staffing is identified by coroners’ reports and inquiries as a key factor. The Health Select Committee 2009 report states: ‘inadequate staffing levels have been major factors in undermining patient safety in a number of notorious cases’. In one year the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) recorded more than 30,000 patient safety incidents related to staffing problems.”

Indeed, as the RCN go on to say, staffing levels constitute part of the wider “business case”:

“The financial context means we need to ensure services are staffed cost-effectively. Many of the identified high impact actions and efficiency measures proposed rely on reducing costs by minimising the expense of avoidable complications such as DVTs (deep vein thrombosis), pressure ulcers and UTIs (urinary tract infections). But ‘avoidable complications’ are only avoidable if effective nursing care is consistently delivered. This relies on having sufficient nurses with the right skills in place – which depends on robust planning in terms of nursing staff resources.”

The Health and Safety Executive provide the following useful information about staffing levels and safety:

“The term ‘staffing levels’ refers to having the right people in the right place at the right time. It is not just a matter of having enough staff, but also ensuring that they have suitable knowledge, skill and experience to operate safely. Economic pressures to save costs and improve productivity, as well as organisational initiatives to delayer, multi-skill and enhance team working, have had the effect of reducing staffing levels. Reductions in staffing levels do not necessarily pose a direct threat to health and safety. Rather, the impact of changes to staffing arrangements on health and safety performance will depend on the quality of the planning, assessment, implementation and monitoring. Health and safety should be managed in the same planned and informed manner as all other elements of reorganisation.”

The issue of whether NHS Foundation Trusts are open to freedom of information requests is complicated. Public authorities often enter into outsourcing and private finance initiative (PFI) arrangements with the private sector to run services or deliver capital projects. These are often the subject of complex requests for information under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FoI). Sometimes the private sector will hold the requested information and the public authority will have access to it but on restricted terms. The question arises: who holds the information for the purposes of FoI? Section 3(2) of the act states: ‘For the purposes of this act, information is held by a public authority if: (a) it is held by the authority, otherwise than on behalf of another person; or (b) it is held by another person on behalf of the authority.’

The guidance of exemptions from the Freedom of Information Act by the Ministry of Justice is extensive (“Guidance”). Section 43 exempts information, disclosure of which would be likely to prejudice the commercial interests of any person. An example of ‘commercially sensitive information might be a “trade secret”. Section 43(1) exempts information if it constitutes a trade secret. The FOI Act does not define a trade secret, nor is there a precise definition in English law. However it is generally agreed that a trade secret must be information used in a trade or business; is information which, if disclosed to a competitor, would be liable to cause real (or significant) harm to the owner of the secret; and the owner must limit the dissemination of the information, or at least, not encourage or permit widespread publication. According to this Guidance, a department’s, or other body’s, commercial interests might, for example, be prejudiced where a disclosure would be likely to: damage its business reputation or the confidence that customers, suppliers or investors; it may have in it have a detrimental impact on its commercial revenue or threaten its ability to obtain supplies or secure finance; or weaken its position in a competitive environment by revealing market-sensitive information or information of potential usefulness to its competitors.

It appears that the research is consistent with the notion that unionised workforces can promote health and safety. For example in “Trade union recognition and the independent health care sector: A literature review for the Royal College of Nursing”, it is proposed that:

“A briefing produced by the TUC (2004) cited a wide range of national and international sources demonstrating the beneficial role played by trade unions in promoting health and safety at work. Workplaces with unions playing a safety role showed injury reduction rates of between 24 and 50 per cent. Observation of health and safety regulations was also shown to be substantially higher in unionised workplaces.”

The answers given by Jeremy Hunt about freedom of information thus far have been extremely unhelpful. See for example the Hansard report of Helen Jones’ question (Helen Jones is the Labour MP for Warrington North) on 11 June 2013 on the subject of “NHS Accountability”:

When the current language has been very much of “parity”, as per the “Fair Playing Field” review of the healthcare economic regulator “Monitor”, it is plainly counterintuitive that freedom of information will apply to some parts of the healthcare sector but not all. Logically, either the whole healthcare sector becomes opaque to freedom of information (as is currently the case), but this does not make sense when only this week Jeremy Hunt was singing the joys of “transparency” in the Commons Health Select Committee. The law generally has been slow to catch up with the formidable challenges in regulating against examples of pathological toxic cultures in the NHS. Clinical negligence can attempt to prove on the balance of probabilities breaches in a duty of care on the law of tort route, and indeed the clinical regulators can in theory encourage Doctors to report other people for a fall in acceptable standards, including adequate resources in hospitals. The law could even prosecute for misuse of public office in theory. However, all of these have proved to be impractical, and the number of sanctions or prosecutions has been relatively low. In this jurisdiction, and elsewhere (particularly the US), there has been a long narrative about whether it is possible to “pierce the corporate veil”, in a fashion of incremental judge-made law, but by far the easiest solution is for Parliament simply to legislate on this. The current Health Select Committee with its formidable membership is well placed to make recommendations to parliament. Certainly, the judiciary would presumably agree that manning a NHS ward with a safe number and quality of nurses is in the public interest, and rather than relying on the judiciary to remedy a suboptimal situation after the event (through intricate consideration of public interest disclosure and whistleblowing and other remedies), it might be more helpful if the legislature could do something before the horse has bolted. The savings in “the Nicholson Challenge” have been described as ‘bureaucratic’ in yesterday’s “Estimates” debate, and there is no sign of this abating (see for example the comment made by Stephen Dorrell MP, head of the Health Select Committee (HSC)):

When the current language has been very much of “parity”, as per the “Fair Playing Field” review of the healthcare economic regulator “Monitor”, it is plainly counterintuitive that freedom of information will apply to some parts of the healthcare sector but not all. Logically, either the whole healthcare sector becomes opaque to freedom of information (as is currently the case), but this does not make sense when only this week Jeremy Hunt was singing the joys of “transparency” in the Commons Health Select Committee. The law generally has been slow to catch up with the formidable challenges in regulating against examples of pathological toxic cultures in the NHS. Clinical negligence can attempt to prove on the balance of probabilities breaches in a duty of care on the law of tort route, and indeed the clinical regulators can in theory encourage Doctors to report other people for a fall in acceptable standards, including adequate resources in hospitals. The law could even prosecute for misuse of public office in theory. However, all of these have proved to be impractical, and the number of sanctions or prosecutions has been relatively low. In this jurisdiction, and elsewhere (particularly the US), there has been a long narrative about whether it is possible to “pierce the corporate veil”, in a fashion of incremental judge-made law, but by far the easiest solution is for Parliament simply to legislate on this. The current Health Select Committee with its formidable membership is well placed to make recommendations to parliament. Certainly, the judiciary would presumably agree that manning a NHS ward with a safe number and quality of nurses is in the public interest, and rather than relying on the judiciary to remedy a suboptimal situation after the event (through intricate consideration of public interest disclosure and whistleblowing and other remedies), it might be more helpful if the legislature could do something before the horse has bolted. The savings in “the Nicholson Challenge” have been described as ‘bureaucratic’ in yesterday’s “Estimates” debate, and there is no sign of this abating (see for example the comment made by Stephen Dorrell MP, head of the Health Select Committee (HSC)):

“It is against that background that the Committee recommends in paragraph 16 of the report on health and social care:

“In our view it would be unwise for the NHS to rely on any significant net increase in annual funding in 2015-16 and beyond. Given trends in cost and demand pressures, the only way to sustain or improve present service levels in the NHS will be to continue the disciplines of the Nicholson Challenge after 2015, focusing on a transformation of care through genuine and sustained service integration.””

As is generally the case in medicine, prevention is better than cure, and it would be most helpful if the law could adopt this approach too. However, the good news is that nurses can participate in the Nursing Times “Speak Out Safely” campaign: “to help bring about an NHS that is not only honest and transparent but also actively encourages staff to raise the alarm and protects them when they do so.” Their Twitter is @NursingTimesSOS.

This inevitably is a complex problem, but requires a solution fast.

Is the answer to abject failure of medical regulation yet more regulation?

There are parallels with the discussion of whether the financial sector was too lightly regulated in the events in the global financial crash. This also happened under Labour’s watch. And Labour got a fair bit of blame for that, despite the Conservatives appearer to wish the regulation in that sector to be even “lighter”. Despite uncertainties about the number of people who actually died at Mid Staffs, for statistical reasons, there is a consensus there are clear examples of care which fell below the standard of the duty-of-care. Such breach caused damage, within an accept time period of remoteness, causing different forms of damage. The problem in this chain of the tort of regulation is that there appears to have been little in the way of damages. It is clear that the regulatory bodies have found it difficult to process their cases in a timely fashion in such a way that even some members of the medical profession and the public have found distressing and unproductive. The medical regulators are, however, fiercely concerned about their reputation, which is why any rumour that you have beeen involved in a cover up, ahead of patient safety, is potentially deadly.

There is a mild sense of panic amongst government ranks, with the introduction of a ‘Chief Inspector of Hospitals’, conducting OFSTED type assessments, and a “legal duty of candour”. It is proposed that this new legal duty might apply to institutions rather than individuals, unless Don Berwick, currently running for Governor of Massachussetts, has any better ideas in the interim. Here is the first problem; the GMC and other clinical councils take a punitive retributive approach (if not restorative), rather than rehabilitative, and Sir Robert Francis QC has emphasised that this is a wider culture malaise where it is difficult to find ‘scapegoats’. Organisations such as Cure however point to the fact that nobody appears to have taken responsibility, and are reported to have a shortlist of people who they’d like to see be in the firing line over Mid Staffs. The GMC is not in the business of blaming organisations, only individuals. In fact, its code (GMC’s “Duty of a Doctor”) is set up so that Doctors can report other Doctors to the GMC, and even report Managers to the GMC.

There is a possibility that NHS managers are not even aware of the professional code of the Doctors who comprise a key part of the workforce, but paragraph 56 of the GMC’s “Duties of a Doctor” is pivotal in demanding Doctors see their patients on the basis of clinical need. This is this clause which provides the tension with the A&E “four hour wait target”, but it is perhaps rather too late for medics to flex their professional muscles over this years after its introduction.

56. You must give priority to patients on the basis of their clinical need if these decisions are within your power. If inadequate resources, policies or systems prevent you from doing this, and patient safety, dignity or comfort may be seriously compromised, you must follow the guidance in paragraph 25b.

Paragraph 25b provides the trigger where Doctors have a duty in their Code to let their NHS manager know:

25. You must take prompt action if you think that patient safety, dignity or comfort is or may be seriously compromised. (b) If patients are at risk because of inadequate premises, equipment*or other resources, policies or systems, you should put the matter right if that is possible. You must raise your concern in line with our guidance11 and your workplace policy. You should also make a record of the steps you have taken.

And indeed following the legal trail, according to the CPS, a person holding “public office” can have committed the offence of “misconduct in a public office” if he or she does not act on such concerns, according to current guidance:

Misconduct in public office is an offence at common law triable only on indictment. It carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. It is an offence confined to those who are public office holders and is committed when the office holder acts (or fails to act) in a way that constitutes a breach of the duties of that office. The Court of Appeal has made it clear that the offence should be strictly confined. It can raise complex and sometimes sensitive issues. Prosecutors should therefore consider seeking the advice of the Principal Legal Advisor to resolve any uncertainty as to whether it would be appropriate to bring a prosecution for such an offence.

(current CPS guidance)

It is a legal point whether a NHS CEO meets the definition of a person holding “public office”. However, few will see little point in a Doctor, however Junior or Consultant, reporting a hospital manager to the GMC for lack of resources. The GMC indeed have a confidential helpline where Doctors can voice concerns about patient safety, even other colleagues, but this itself is fraught with practical considerations, such as when data are disclosed beyond confidentiality and consent, or a duty for the GMC not to encourage an avalanche of vexatious and time-consuming complaints either.

Indeed, the whole whistleblower affair has blown up because whistleblowers feel they have to make a disclosure for the purpose of patient safety in an unsupporting environment, often directly to the media, because nobody listens to them at best, or they get subject to detrimental behaviour (humiliation or bullying, for example) at worst. Clinical staff will not wish to get involved in lengthy GMC investigations about their hospital, and it would be interesting to see how many the actual number which have resulting in any form of sanction actually is. This is even amidst the backdrop that more than half of nurses believe their NHS ward or unit is dangerously understaffed, according to a recent survey, reported in February 2013. The Nursing Times conducted an online poll of nearly 600 of its readers on issues such as staffing, patient safety and NHS culture. Three-quarters had witnessed what they considered “poor” care over the past 12 months, the survey found. Understaffing in clinical wards has been identified as a cause of nurses working at a pace beyond what they are comfortable with, and the subsequent effects on patient safety are succinctly explained by Jenni Middleton (@NursingTimesEd) and colleagues in their video for the “Nursing Times Speak Out Safely” campaign.

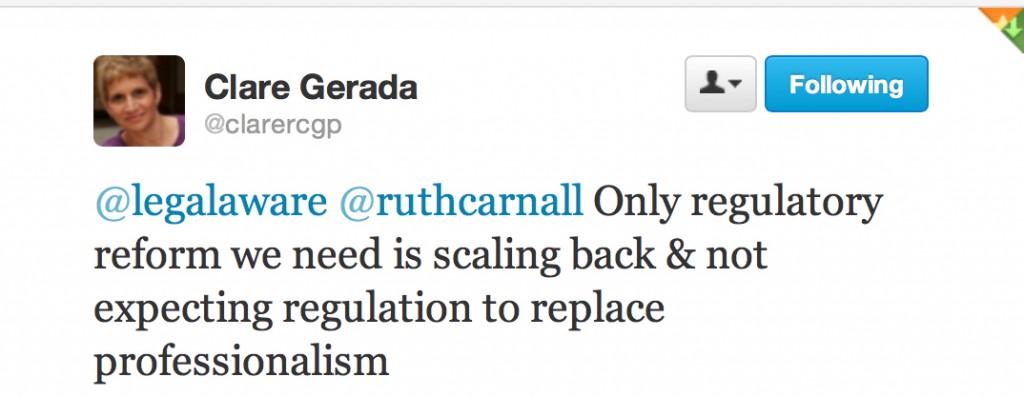

In the same way, the cure for recession may not be more spending (this is a moot point), the answer to a failure of medical regulation may not be yet further regulation. The temptation is to add an extra layer of regulation, such as an OFHOSP body which goes round investigating hospitals, but we have already introduced a ‘Chief Inspector of Hospitals’. At worst, further regulation encourages a culture of intimidation and secrecy, and Prof Clare Gerada clearly does not believe the NHS being caught up in yet further regulation is practicable or advisable:

And yet most would agree, following Mid Staffs and the revelations over CQC at the weekend that ‘doing nothing is NOT an option’ (while conceding that a “moral panic” response cannot be appropriate either.) The fundamental problem is that this policy gives all the impression of being designed in response to a crisis, how acute medics work in ‘firefighting’. Likening patient safety to the economy, it might be more fruitful to focus attentions to the other end of the system. This is the patient safety equivalent of turning attention from redistributive (or even punitive) taxation to predistribution measures such as the living wage. Some advocates call for a greater emphasis on compassion, and reducing the number of admissions seen in the Medical Admissions Unit or A&E, but in a sense we are coming full-circle again in the underlying argument of an under-resourced ward being an unsafe one. Transplant on this a political mantra that the main parties have had divergent views about whether NHS spending is adequate now or has been adequate before, in apparent contradiction to the nearly £3bn savings which were not ploughed back into patient care. or the £2bn suddenly found for the complex implementation of the Health and Social Care Act (2012). The existing regulatory mechanism for complaints to be made about under-resourcing affecting patient safety is there, but the intensity of the incentive for professionals using this mechanism appears to be low. Professionals will argue that they have a professional duty to maintain patient safety regardless of yet further regulation, but professionals have reported the mission creep of deprofessionalism in the NHS for some time now. Here, the medical professions have a mechanism of holding the NHS to account, and, if adverse reports were investigated quickly and acted upon, it is possible that NHS CEOs are not overly rewarded for failure. But if this mechanism is considered unfeasible, along with a “new improved” performance management system incentivising somehow ‘whistleblowing’, it’s back to the drawing board yet again.

To turn the CQC into a “NHS disaster” story is for some hitting a target but totally missing the point

Some very well known people have totally missed the point. They are supposed to be professional commentators or editors. What happened yesterday, with the publication of the long-awaited report by CQC, was not another NHS “disaster story”. Such a story is intended to make you want to go #facepalm at the thought of needing to go into a NHS Trust. It may even be a story to tell you that the NHS is not a “national religion“, and is a ‘sacred cow’ which ought to be sacrificed on the Hayek Altar of Privatisation.

No, I’m being very ironic.

The CQC was set up to expose problems in hospitals and care homes. It had far-reaching powers of inspection which allow it to order reforms or even close health services which put patients at risk. The interviews between James Titcombe and John Humphrys and David Prior, this morning, on the BBC Radio 4 programme are here. The CQC has been found, however, wanting in a drastic way yet again. The BBC TV programme Panorama broadcast evidence of mistreatment on residents of a Castlebeck hospital on May 31, 2011. Despite evidence concerning the same institution having previously been given to the Care Quality Commission, the body failed to act and has since admitted “an unforgivable error of judgment”. Major changes unsurprisingly have been made in the upper echelons of the Care Quality Commission, with a number of senior people leaving the organisation. According to “Caring Times”, its Director of finance and corporate services John Lappin announced he had a new post last year but agreed to stay on to finalise CQC’s budget for 2013/14 and deputy chief executive Jill Finney left CQC in February to take up a senior role in the private sector. Louise Guss, director of governance and legal services, was reported to be set to leave at the end of May, as was director of operations delivery Amanda Sherlock. Director of human resources Allison Beale will apparently leave in September. David Prior is now the Chairman of CQC; his biography is here.

In future, CQC hospital inspections will include 15-20 experienced people for a month, according to David Prior this morning. However, the report published this morning winded an already beleaguered NHS. Regulators apparently deleted the review of their failure to act on concerns about University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Trust, where police are investigating the deaths of at least eight mothers and babies. James Titcombe (@JamesTitcombe) and his wife, Hoa, arrived at the Furness General Hospital at Morecambe Bay, Cumbria, on 27 October 2008. Their son, Joshua, was born that morning. Nine days later, James Titcombe, a nuclear engineer from Barrow-in-Furness, tragically witnessed his son die. Midwives and medical staff at Furness General had failed to detect and monitor an infection, which became so serious that Joshua had to be transferred for intensive care at two different hospitals. Joshua died on 5 November. James has led a very public campaign for a public inquiry into “serious systemic failures” at the University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay Trust which manages Furness General. The horrific story is laid bare by James in this account here.

Kay Sheldon (@kayfsheldon), a director of the Care Quality Commission, also accused its senior managers of “deceit and evasion” in refusing to be straightforward about its failings. Kay sits on the CQC’s board as a non-executive director, and her role is to hold it to account. She has now spoken out, having refused to sign a wide-ranging gagging order in the wake of attempts to have her removed by the former chairman after she gave evidence about its failings to the Mid Staffs inquiry. James was asked about the situation now.

“… One of the key things is… One of the things I need to say John [Humphrys] is how amazingly grateful I am to Kay Sheldon as a non-executive Director. This report would not have come out if it were not for Kay. She was very courageous, and she faced what whistleblowers often face in the NHS, which is a vilification of their actions, ..in quite an appalling way. This report vindicates those concerns, and I think CQC – and David Prior to whom you’re talking afterwards – could demonstrate a commitment to the kind of the culture people want to see. David Prior could publicly reinstate Kay Sheldon and will remain on the board of CQC. That would go a long way. Other than that, I will judge the CQC how it will react in the next few weeks, and lays out its proposals how nothing like this can ever happen again.”

The chairman of the CQC, David Prior, who has been in the post for four months, said he was “desperately sorry” that the situation had arisen.

Particularly in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, all the international financial regulators have reciprocal relationships to help them conduct their duties of public protection by sharing information. Any lack of sharing of information in a facilitatory way may be a fundamental barrier to effective regulation in healthcare, and time will tell. Prior said that,

“Unbeknown to us there was an investigation being held by Pauline Fielding which had been going on for four months, and found the maternity service was dysfunctional and unsafe. Her report was not finished at the time. We were not set up then and we are now set down to inspect hospitals…Our job is to inspect hospitals. We sent people in who had not worked in a hospital before. How could they do a proper job? We have been in the job of giving reassurances to the public.”

Among the various findings, the CQC was “accused of quashing an internal review that uncovered weaknesses in its processes“. David Prior was asked this morning by John Humphrys why one person in the CQC was asked to “destroy” evidence, to which Prior said that the “management board was dysfunctional.”

“I had known for a few months that we were not ‘fit for purpose’ as far as hospital inspections are concerned.”

Humphrys asked repeatedly if anybody who had left CQC were “punished”, and Prior said no. This issue of people moving on from failures in one job in NHS management to get a highly paid job elsewhere continues to haunt the NHS. Caroline Molloy very recently on the ‘Our NHS’ blog has described how this phenomenon has gathered momentum pursuant to the Health and Social Care Act (2012):

“In an increasingly marketised system, the opportunities for financial conflicts of interests are clear. It is curious that the media has chosen to focus on the conflicts of commissioning GPs. Whilst problematic, the sums involved are dwarfed by the huge fortunes to be made by the corporate clients of the big four currently embedding themselves at the heart of policy making.”

In August 2012 David Behan, chief executive of CQC, commissioned a report by management consultants, Grant Thornton. Names of those accused of a cover-up within the CQC were removed from this report. Humphrys explictly asked why the names in this Report had been redacted. Prior answered, “We had to make the decision on Friday to not publish the Report or publish the Report with the names, but we would have been breaching the Health Protection Act.” However, @dbanksy later on Twitter reported that:

Anyone who knows how English law works will know that the English law is there for all parties to interpret freely. A person will pay for legal advice, instruct the lawyer according to what result he or she wants. If a party were to instruct a lawyer to protect the identities of certain individuals, rather than to disclose a narrative which is clearly in the ‘public interest’, that would be perfectly possible. It would also be perfectly possible to instruct a different lawyer with different instructions. Get this – Hunt can sue the CQC if he wants. The NHS and CQC are not the same thing, shock horror!

Incredibly, some accounts failed to mention even Kay Sheldon, a key member of all this. James Titcombe was incredibly impressive as ever, in articulating what is clearly not a vendetta against the NHS, but an earnest desire for everyone in the NHS to learn from its mistakes. There are issues about what happened to Kay’s opinions, why healthcare regulators appear to coordinate poorly their regulatory inquiries, and the concerns of Kay Sheldon and a similar band of people Dr Heather Wood, David Drew, Dr Kim Holt, who have become sacrificial lambs in the whole cathartic process. People who whistleblow tend never to work again in the #NHS, and, for all the heroism, their opinions are marginalised at best, at worst ridiculed and humiliated. This episode is very clearly a debate about the efficacy of healthcare regulation. There is an urgent question to be had about the efficacy of the CQC’s regulation: why does England persist with a non-specialist “one size fits all” generic method of regulation in some parts? To have turned this into a privatisers’ charter was perhaps hitting the target for some, but missing the point, I feel.

Is it appropriate to blame the pilot of the NHS safety-compliant plane?

Please contact @legalaware if you would like to tweet constructively with the author about the ideas contained herewith.

The “purpose” of an air plane crash investigation is apparently as set out in the tweet below:

It seems appropriate to extend the “lessons from the aviation industry” in approaching the issue of how to approach blame and patient safety in the NHS. Dr Kevin Fong, NHS consultant at UCHL NHS Foundation Trust in anaesthetics amongst many other specialties, highlighted this week in his excellent BBC Horizon programme how an abnormal cognitive reaction to failure can often make management of patient safety issues in real time more difficult. Approaches to management in the real world have long made the distinction between “managers” and “leaders” and it is useful to consider what the rôle of both types of NHS employees might be, particularly given the political drive for ‘better leadership’ in the NHS.

In corporates, reasons for ‘denial about failure’ are well established (e.g. Richard Farson and Ralph Keyes writing in the Harvard Business Review, August 2002):

“While companies are beginning to accept the value of failure in the abstract-at the level of corporate policies, processes, and practices-it’s an entirely different matter at the personal level. Everyone hates to fail. We assume, rationally or not, that we’ll suffer embarrassment and a loss of esteem and stature. And nowhere is the fear of failure more intense and debilitating than in the competitive world of business, where a mistake can mean losing a bonus, a promotion, or even a job.”

Farson and Keyes (2011) identify early-on for potential benefits of “failure-tolerant leaders”:

“Of course, there are failures and there are failures. Some mistakes are lethal-producing and marketing a dysfunctional car tire, for example. At no time can management be casual about issues of health and safety. But encouraging failure doesn’t mean abandoning supervision, quality control, or respect for sound practices, just the opposite. Managing for failure requires executives to be more engaged, not less. Although mistakes are inevitable when launching innovation initiatives, management cannot abdicate its responsibility to assess the nature of the failures. Some are excusable errors; others are simply the result of sloppiness. Those willing to take a close look at what happened and why can usually tell the difference. Failure-tolerant leaders identify excusable mistakes and approach them as outcomes to be examined, understood, and built upon. They often ask simple but illuminating questions when a project falls short of its goals:

- Was the project designed conscientiously, or was it carelessly organized?

- Could the failure have been prevented with more thorough research or consultation?

- Was the project a collaborative process, or did those involved resist useful input from colleagues or fail to inform interested parties of their progress?

- Did the project remain true to its goals, or did it appear to be driven solely by personal interests?

- Were projections of risks, costs, and timing honest or deceptive?

- Were the same mistakes made repeatedly?”

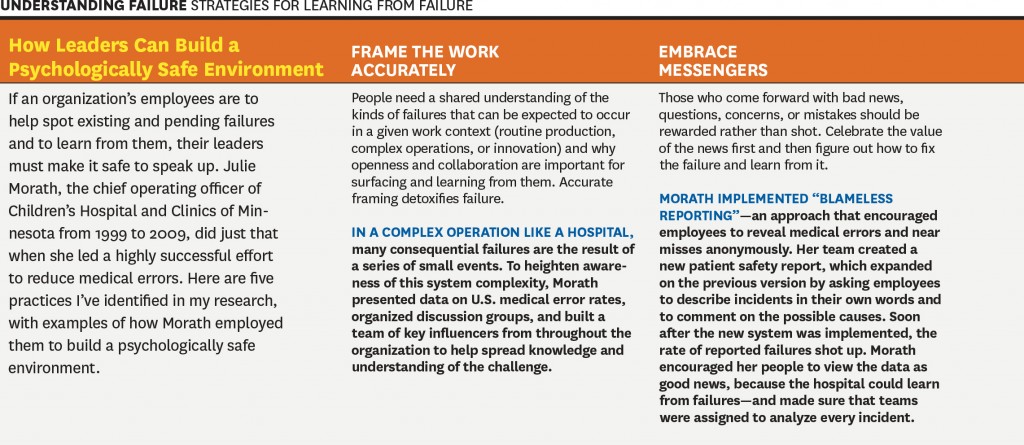

It is incredibly difficult to identify who is ‘accountable’ or ‘responsible’ for potential failures in patient safety in the NHS: is it David Nicholson, as widely discussed, or any of the Secretaries of States for health? There is a mentality in the popular media to try to find someone who is responsible for this policy, and potentially the need to attach blame can be a barrier to learning from failure. For example, Amy C Edmondson also in the Harvard Business Review writes:

“The wisdom of learning from failure is incontrovertible. Yet organizations that do it well are extraordinarily rare. This gap is not due to a lack of commitment to learning. Managers in the vast majority of enterprises that I have studied over the past 20 years—pharmaceutical, financial services, product design, telecommunications, and construction companies, hospitals, and NASA’s space shuttle program, among others—genuinely wanted to help their organizations learn from failures to improve future performance. In some cases they and their teams had devoted many hours to after-action reviews, post mortems, and the like. But time after time I saw that these painstaking efforts led to no real change. The reason: Those managers were thinking about failure the wrong way.”

Learning from failure is of course extremely important in the corporate sectors, and some of the lessons might be productively transposed to the NHS too. This is from the same article:

However, is this is a cultural issue or a leadership issue? Michael Leonard and Allan Frankel in an excellent “thought paper” from the Health Foundation begin to address this issue:

“A robust safety culture is the combination of attitudes and behaviours that best manages the inevitable dangers created when humans, who are inherently fallible, work in extraordinarily complex environments. The combination, epitomised by healthcare, is a lethal brew.

Great leaders know how to wield attitudinal and behavioural norms to best protect against these risks. These include: 1) psychological safety that ensures speaking up is not associated with being perceived as ignorant, incompetent, critical or disruptive (leaders must create an environment where no one is hesitant to voice a concern and caregivers know that they will be treated with respect when they do); 2) organisational fairness, where caregivers know that they are accountable for being capable, conscientious and not engaging in unsafe behaviour, but are not held accountable for system failures; and 3) a learning system where engaged leaders hear patients and front-line caregivers’ concerns regarding defects that interfere with the delivery of safe care, and promote improvement to increase safety and reduce waste. Leaders are the keepers and guardians of these attitudinal norms and the learning system.”

Whatever the debate about which measure accurately describes mortality in the NHS, it is clear that there is potentially an issue in some NHS trusts on a case-by-case issue (see for example this transcript of “File on 4″‘s “Dangerous hospitals”), prompting further investigation through Sir Bruce Keogh’s “hit list“) Whilst headlines stating dramatic statistics are definitely unhelpful, such as “Another nine hospital trusts with suspiciously high death rates are to be investigated, it was revealed today”, there is definitely something to investigate here.

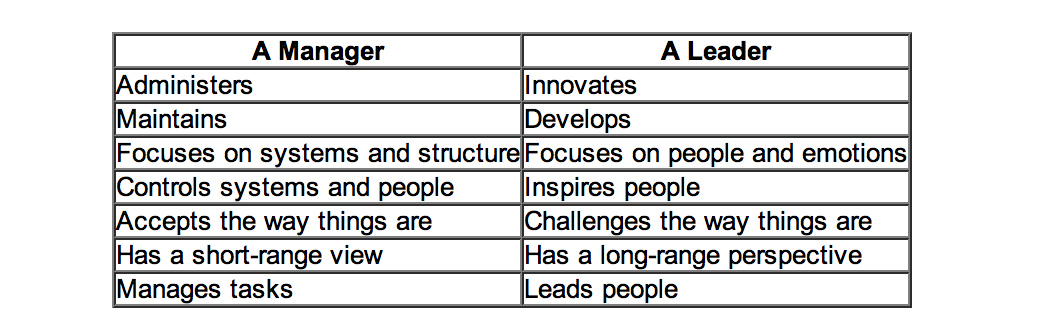

Is this even a leadership or management thing? One of the most famous distinctions between managers and leaders was made by Warren Bennis, a professor at the University of Southern California. Bennis famously believes that, “Managers do things right but leaders do the right things”. It is argued that doing the right thing, however, is a much more philosophical concept and makes us think about the future, about vision and dreams: this is a trait of a leader. Bennis goes on to compare these thoughts in more detail, the table below is based on his work:

Indeed, people are currently scrabbling around now for “A new style of leadership for the NHS” as described in this Guardian article here.

Is patient safety predominantly a question of “teamwork”?

Amalberti et al. (2005) make some interesting observations about teamwork and professionalism:

“A growing movement toward educating health care professionals in teamwork and strict regulations have reduced the autonomy of health care professionals and thereby improved safety in health care. But the barrier of too much autonomy cannot be overcome completely when teamwork must extend across departments or geographic areas, such as among hospital wards or departments. For example, unforeseen personal or technical circumstances sometimes cause a surgery to start and end well beyond schedule. The operating room may be organized in teams to face such a change in plan, but the ward awaiting the patient’s return is not part of the team and may be unprepared. The surgeon and the anesthesiologist must adopt a much broader representation of the system that includes anticipation of problems for others and moderation of goals, among other factors. Systemic thinking and anticipation of the consequences of processes across depart- ments remain a major challenge.”

Weisner et al. (2010) have indeed observed that:

“Medical teams are generally autocratic, with even more extreme authority gradient in some developing countries, so there is little opportunity for error catching due to cross-check. A checklist is ‘a formal list used to identify, schedule, compare or verify a group of elements or… used as a visual or oral aid that enables the user to overcome the limitations of short-term human memory’. The use of checklists in health care is increasingly common. One of the first widely publicized checklists was for the insertion of central venous catheters. This checklist, in addition to other team-building exercises, helped significantly decrease the central line infection rate per 1000 catheter days from 2.7 at baseline to zero.”

M. van Beuzekom et al. (2013) and colleagues, additionally, describe an interesting example from the Netherlands. Teams in healthcare are co-incidentally formed, similar to airline crews. The teams consist of members of several different disciplines that work together for that particular operation or the whole operating day. This task-oriented team model with high levels of specialization has historically focused on technical expertise and performance of members with little emphasis on interpersonal behaviour and teamwork. In this model, communication is informally learned and developed with experience. This places a substantial demand on the non-clinical skills of the team members, especially in high-demand situations like crises.

Bleetman et al. (2011) mention that, “whenever aviation is cited as an example of effective team management to the healthcare audience, there is an almost audible sigh.” Debriefing is the final teamwork behaviour that closes the loop and facilitates both teamwork and learning. Sustaining these team behaviours depends on the ability to capture information from front-line caregivers and take action. In aviation, briefings are a ‘must-do’ are not an optional extra. They are performed before every take-off and every landing. They serve to share the plan for what should happen, what could happen, to distribute the workload efficiently and to prevent and manage unexpected problems. So how could we fit briefings into emergency medicine? Even though staff may be reluctant to leave the computer screen in a busy department, it is likely to be worth assembling the team for a few minutes to provide some order and structure to a busy department and plan the shift.

Briefing points could cover:

- The current situation

- Who is present on the team and their experience level

- Who is best suited to which patients and crises so that the most effective deployment of team members occurs rathe than a haphazard arrangement

- The identification of possible traps and hazards such as staff shortages ahead of time

- Shared opinions and concerns.

The authors describe that, “at the end of the shift a short debriefing is useful to thank staff and identify what went well and what did not. Positive outcomes and initiatives can be agreed.”

Is patient safety predominantly a question of “leadership”?

The literature identifies that overall team members are important who have a good sense of “situational awareness” about the patient safety issue evolving around them. However, it is being increasingly recognised that to provide effective clinical leadership in such situations, the “team leader” needs to develop a certain set of non-clinical skills. This situation demands more than currency in advance paediatric life support or advanced trauma life support; it requires the confidence (underpinned by clinical knowledge) to guide, lead and assimilate information from multiple sources to make quick and sound decisions. The team leader is bound to encounter different personalities, seniority, expectations and behaviours from members of the team, each of whom will have their own insecurities, personality, anxieties and ego.

Amalberti et al. (2005) begin to develop a complex narrative on the relationship between leadership and management (and the patients whom “they serve”):

“Systems have a definite tendency toward constraint. For example, civil aviation restricts pilots in terms of the type of plane they may fly, limits operations on the basis of traffic and weather conditions, and maintains a list of the minimum equipment required before an aircraft can fly. Line pilots are not allowed to exceed these limits even when they are trained and competent. Hence, the flight (product) offered to the client is safe, but it is also often delayed, rerouted, or cancelled. Would health care and patients be willing to follow this trend and reject a surgical procedure under circumstances in which the risks are outside the boundaries of safety? Physicians already accept individual limits on the scope of their maximum performance in the privileging process; societal demand, workforce strategies, and competing demands on leadership will undermine this goal. A hard-line policy may conflict with ethical guidelines that recommend trying all possible measures to save individual patients.”

Conclusion

Even if one decides to blame the pilot of the plane, one has to wonder the extent to which the CEO of the entire airplane organisation might to be blame. The question for the NHS has become: who exactly is the pilot of plane? Is it the CEO of the NHS Foundation Trust, the CEO of NHS England, or even someone else? And rumbling on in this debate is whether the plane has definitely crashed: some relatives of passengers are overall in absolutely no doubt that the plane has crashed, and they indeed have to live with the wreckage daily. Politicians have then to decide whether the pilot ought to resign (has he done something fundamentally wrong?) or has there been something fundamentally much more distal which has gone wrong with his cockpit crew for example? And, whichever figurehead is identified if at all for any problems in this particular flights, should the figurehead be encouraged to work in a culture where problems in flying his plane have been identified and corrected safely? And finally is this is a lone airplane which has crashed (or not crashed), and are there other reports of plane crashes or near-misses to come?

References

Learning from failure

Richard Farson and Ralph Keyes. The Failure Tolerant Leader. Harvard Business Review: August 2002.

Amy Edmondson. Strategies for learning from failure. Harvard Business Review: April 2011.

Patient safety

Amalbert, R, Auroy, Y, Berwick, D, Barach, P. Five System Barriers to Achieving Ultrasafe Health Care Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:756-764.

Bleetman, A, Sanusi, S, Dale, T, Brace. (2012) Human factors and error prevention in emergency medicine. Emerg Med J 2012;29:389e393. doi:10.1136/emj.2010.107698

Federal Aviation Administration. Section 12: Aircraft Checklists for 14 CFR Parts 121/135 iFOFSIMSF.

Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S et al. (2006) An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med 355:2725–32.

van Beuzekom, M, Boer, F, Akerboom, S, Dahan, A. (2013) Perception of patient safety differs by clinical area and discipline. British Journal of Anaesthesia 110 (1): 107–14 (2013)

Weisner, TG, Haynes, AB, Lashoher, A, Dziekman, G, Moorman, DJ, Berry, WR, Gawande, AA. Perspectives in quality: designing the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist. (2010) International Journal for Quality in Health Care Volume 22, Number 5: pp. 365–370

Why are Labour and the National Health Action Party playing so hard-to-get with each other?

This is a totally independent post and does not represent the views of the Socialist Health Association.

Despite being a rather corporate slogan, ‘diversity’ is much valued, and maybe Labour should welcome a new ‘kid on the block’? If the next big thing of 2012 was ‘muscular liberalism’, perhaps Labour should not adopt a stance of ‘divisive socialism’ against newbies, the National Health Action Party (@NHAParty). Why are Labour and the National Health Action Party playing so hard-to-get with each other? This issue has been all-the-more crucial to address with the imminent by-election in the safe Tory/LibDem seat of Eastleigh.

No doubt Labour will have a full frontal range of attitudes and emotions towards the National Health Action Party: in my circle of followers on Twitters, opinions have ranged from, “they’re definitely worth listening to” to “they’ll be lucky if they get 10 votes”. Labour cannot escape from discussing the NHS, even if it feels it can still play a ‘strong hard’, but much like all else they do they run the risk of taking Labour voters for granted on the NHS.

Dr Clive Peedell (@cpeedell) doesn’t want the creeping marketisation of the NHS to go any further. Andy Burnham MP (@andyburnhammp) was the person who ventured out into ‘NHS global’, so that Foundation Trusts could sell their products abroad under the NHS logo, and who continued the march of the NHS Foundation Trust machine.

However, Andy feels now ‘enough-is-enough’. Despite being from the Labour (and some would say “New Labour”) stable, Andy has signalled that he wishes to repeal the Health and Social Care Act (2012). Of course, reversing the changes in it presents a more formidable challenge, but Andy says that he wishes to reverse Part 3 of the Act. This is code for getting rid of the fact that private companies, to which the NHS has been increasingly outsourced, will not be ‘competing’ to do what the NHS is supposed to do, using the NHS logo to maximise their own shareholder dividend. The unfortunate effect of engaging domestic and international competition law has become the ludicrous situation where the NHS cannot be given any preferential treatment for fear of offending European law, ‘distorting’ the market and so on.

There are strong economic arguments for not running the NHS in a fragmented piecemeal outsourced fashion; not least the NHS can benefit economically from ‘economies-of-scale’ and there is hope that with the proper leadership it can further national policy. Unfortunately, Sir David Nicholson and his army have stayed in situ when cultural change, when – in fact – a new charismatic change leader, is need to drive a move away from his failed ‘efficiency savings’. Efficiency was managerial speak for a Frederick Taylor-approach to management, looking at productivity and activity, meaning that one Foundation Doctor would be running around all the geriatric wards for the whole-of-the-night while his or her colleague was doing all the geriatric admissions in Casualty, to save money. The fact that you cannot have ‘something for nothing’, a popular philosophy of Thatcher, is borne out by the 400-1200 deaths in Stafford, where the inaction by the health regulatory bodies has been striking, and the political reaction somewhat confused.

In innovation, it’s possible for a new entrant to dislodge an incumbent by a slight subtlety. That is the basis of the splendid body of work by Prof Clay Christensen at Harvard Business School. However, nobody is expecting the NHA Party, co-founded by Dr Clive Peedell, a NHS oncologist, to dislodge Labour. However, Labour have openly admitted that Eastleigh is 285th on their “hit list”, so many question indeed Ed Miliband’s wisdom in spectacularly losing a safe Hampshire seat.

We have seen coalitions can work for one of the parties within it. We have also seen single-issue parties getting MPs somehow, such as Caroline Lucas in Brighton. If you park aside the perceived differences of NHA Party and Labour, given that Labour is “the party of the NHS” with its own brand loyalty, it might be conceded that Labour not winning does not further the NHS debate. It is possible that, as a protest vote against the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats, the NHA Party do indeed have a fighting chance of getting one MP.

And what is the point of one MP? Well what is the point of a handful of Liberal Democrats? In practice management techniques, such as PRINCE2, it is customary for there to be a ‘senior user’ as well as a ‘senior customer’ on your project board. While many will balk at the idea of ‘customers’ of NHS, unlike Prof Karol Sikora at the weekend on BBC’s “Sunday Politics”, there is a lot to be said, arguably, for input from frontline doctors and other healthcare staff in the NHS debate.

To delve into business management speak, which has possibly crippled the NHS thus far, the NHA Party and Labour have important synergies in values and competences in their outlook on the NHS. Ironically, there is an active debate about how collaboration, as well as (or rather than) competition, should be encouraged. It might be time to ‘think the unthinkable’, and consider the vague possibility that Labour, while desperately trying to fight for an electoral majority in 2015 despite the statistical odds, might benefit from a strategic alliance, or partnership, with the NHA Party. This does not need to be a formal joint venture, but, to expand the business analogy, could be a clever way for Labour to reaffirm its commitment to the NHS and for the NHA Party to gain ‘market entry’. Given that the traditional media appear not to allow the NHA Party to discuss the agenda fully, this may not be a bad thing, I feel.

Please feel free to contact me on @legalaware if you wish to have a constructive debate about any of the issues therein. Many thanks.

A failure of leadership and management: toxic cultures, ENRON and the Francis Report

Robert Francis has an incredibly difficult task. It is difficult for people who have not qualified, even managers and leaders of healthcare think tanks, to understand how this situation has arisen. Being a senior lawyer, his approach will necessarily involve “the law is not enough”. The NHS is currently a “political football”, but the overriding objective must be one of patient safety. Whatever your views about managers following financial targets religiously, and regulatory authorities pursuing their own targets sometimes with equal passion, it is hard to escape from the desire for a national framework for patient safety. This is at a time indeed when it is proposed that the National Health and Patient Safety Agency should be abolished, which indeed has oversight of medical devices and equipment. Indeed, one of the findings of the Francis Inquiry is that essential medical equipment was not always available or working. A general problem with the approach of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) has been the abolition of ‘national’ elements, such as abolition of the Health Protection Authority. (more…)

Robert Francis has an incredibly difficult task. It is difficult for people who have not qualified, even managers and leaders of healthcare think tanks, to understand how this situation has arisen. Being a senior lawyer, his approach will necessarily involve “the law is not enough”. The NHS is currently a “political football”, but the overriding objective must be one of patient safety. Whatever your views about managers following financial targets religiously, and regulatory authorities pursuing their own targets sometimes with equal passion, it is hard to escape from the desire for a national framework for patient safety. This is at a time indeed when it is proposed that the National Health and Patient Safety Agency should be abolished, which indeed has oversight of medical devices and equipment. Indeed, one of the findings of the Francis Inquiry is that essential medical equipment was not always available or working. A general problem with the approach of the Health and Social Care Act (2012) has been the abolition of ‘national’ elements, such as abolition of the Health Protection Authority. (more…)

Monitor has much work to do to produce a cogent analysis of pricing in healthcare

Monitor is in its infancy, but, pardon the pun, I would like to describe an example of childbirth to explain the mountain of problems that the new privatised NHS is yet to experience. Consider this a steep learning-curve that not many of us voted for at the last election.

“The new NHS provider licence: consultation document” was issued by Monitor on 31 July 2012 with a deadline for responses determined as 23 October 2012. According to section 5.1 of this Document on pricing,

“One of Monitor’s new functions will be to set prices for health care services funded by the NHS.Accurate pricing is essential to ensure that providers are paid appropriately for services they provide to patients. Accurate pricing information helps GPs, commissioners and providers to plan and budget for health care services to meet people’s needs. Pricing can also be used to encourage providers to improve the quality of services for patients, and to increase the efficiency with which services are provided. If providers are not properly reimbursed, this can reduce the quality and efficiency of care they offer and may, in some circumstances, threaten the sustainability of their services.”

Pricing is pivotal in markets, and will obviously therefore be expected to the subject of considerable scrutiny by competition regulatory authorities. In future, Monitor will be responsible, in partnership with the NHS Commissioning Board, for setting prices for NHS services.Indeed, according to a statement produced on 20 June 2012,

“The Health and Social Care Act 2012 makes changes to the way health care is regulated in order to strengthen the way patients’ interests are promoted and protected. Monitor’s role will change significantly as we take on a number of new responsibilities. We will become the sector regulator for health care, which means that we will regulate all providers of NHS-funded services in England, except those that are exempt under secondary legislation.”

Take for example the cost to the taxpayer of a provider delivering a baby – not the antenatal or postnatal packages, but the cost of the actual labour and peri-partum process (“the package”). Like any other “product” in the market, a supplier will have to price its product carefully, to ensure that it offers a competitive price, but especially to ensure it does not price itself out of the market by being too costly. The price of “the package” might be determined through a number of different ways.

- Premium pricing (also called prestige pricing) is the strategy of consistently pricing at, or near, the high end of the possible price range to help attract status-conscious consumers. People might buy a premium priced product because they believe the high price is an indication of good quality.

- Cost-plus pricing is the simplest pricing method. The firm calculates the cost of producing the product and adds on a percentage (profit) to that price to give the selling price. This method although simple has two flaws; it takes no account of demand and there is no way of determining if potential customers will purchase the product at the calculated price. You only need to consider the complexity of doing the calculation for the package”, e.g. will the provider use cheap epipdural needs for the anaesthesia, will a foundation year doctor (who is cheaper) perform most of the medicine compared to a specialist registrar (who is more expensive, but more experienced, especially in dealing with medical emergencies).

- Value-based pricing – a price based on the value the product has for the customer and not on its costs of production or any other factor.. The relevant issue is how much would you be prepared to have provider A deliver your baby? This is a subjective issue, not easy to predict.

The problem with premium pricing is that providers can collude lawfully to set their prices as high as possible between them. Price fixing is illegal under Article 101 TFEU of the European Union:

Article 101

(ex Article 81 TEC)

1. The following shall be prohibited as incompatible with the internal market: all agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices which may affect trade between Member States and which have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the internal market, and in particular those which: