Home » Accountability

Golden handcuffs

“Golden handcuffs” in corporate land are normally financial incentives to stop employees from leaving.

My friend described to me yesterday a different type of “golden handcuffs” at play in his NHS Foundation Trust. I spent an hour with him, a youngish NHS Consultant in England. He works as a general physician. He also has direct links to the RCP, of which he is a senior member. As you would expect, he was knowledgeable about what is happening to the National Health Service, which he adores. But he feels that the system in his Trust has gone very badly wrong. Whilst autonomy and independence of NHS Foundation Trusts are both key features of the policy, he feels it likely that similar behaviours are being emulated in other Trusts. He feels there to be a rife ‘target culture’, led by non-clinicians. This, he attributes, occurred when the new management took over in the Trust, rather than when there was any change in central party politics.

He feels essentially that he and colleagues in the NHS are being ‘bought with silence’. He feels, rather perversely, that awards which promote, say, excellence, leadership or innovation are in fact having an unwanted effect. People, he says, with numerous awards, even if they have strong misgivings about the system, are far less likely to raise concerns. Raising concerns makes it more difficult to get an award; and awards impact on your assessment for clinical excellence awards. The Trust he works in is described as having ‘clinical leaders’ who are essentially ‘yes men’ or ‘wing men’, who “protect” higher management. He’s adamant that management have become really focused on one thing: their own reputation management. However, he does want his tale to be heard, as he feels that there are lessons to be learnt about how clinicians interact with management in the English NHS. He feels that the English NHS has become a joke in the way the system is basically rigged towards not identifying good practice, and not sharing any issues with patients.

The background to this is as follows. To be honest, the coverage of the problems in the NHS had washed over me when it veeered towards a complicated statistical debate. I watched the news coverage like many of us did. We all got a bit sidetracked with the thousands of excess or needless deaths allegations. We wondered about its statistical validity. We wondered about the truth of some of more hyperbolic claims in the media. Some people that it was all a ruse to picture the NHS in a permanent state of turmoil and disaster, interspersed with some quality gems about how fantastic the NHS is. He feels that the NHS as a public service could be superb, but has concerns that the public-run NHS has allowed itself ‘to get into this mess’.

When I mentioned his remarks to someone, that person even said, “Is this guy for real? It’s too good an account. Isn’t it fiction?”

What he described truly shocked me. I’m an avid supporter of the NHS, but what he described was very clearly a system in his Trust which had gone very badly wrong. Even worse, it was extremely unlikely that patients would know about poor quality care because of the resistance of clinical staff and managers to tell the patients. His Foundation Trust is one of the best performing hospital units in England, with one of the best figures for the 4 hour wait. The management is indeed very keen to trumpet loudly this figure. And yet the way the acute medical takes are being run are utterly shambolic, according to him.

He feels that it’s become impossible to monitor the quality of his team’s clinical decision making. There’s no way of ascertaining whether patients were given the best available management steps, as the service is totally uninterested in discussing cases openly. The management prefer to rely on targets instead, and increasingly they’ve stopped measuring certain targets (such as length of stay). A poor length of stay figure in his Trust will invariably be spun as problems in discharging a patient to the community, rather than the notion that the patient was not properly given the correct management in hospital. A mention of ‘C difficile’ on the death certificate would trigger a root cause analysis, however. Because of staffing issues, he only has a skimpy foundation years team, and one Staff Grade; he has no Registrar. Apart from things blatantly going wrong, generating a complaint, there’s no way of telling whether other Doctors are exercising poor judgment in clinical decision-making.

But he does “blame” various people. He blames his management for refusing to acknowledge any bad news, let alone offering any solutions. He doesn’t blame the majority of nurses whom he perceives as being worn out and demoralised by the conditions they’re working in. But he does blame the senior nurses who are trying to spread the idea that everything’s great, for not risking their bonus. And most of all he blames other Consultants for mostly keeping silent about the poor medical management of the patients. He says he presents his findings at the Grand Round, and senior consultants often come up to him to thank him for being problems. But in the same breath he says nothing of ‘them’ report the same problems. He says of all the people it’s the junior medics who are likely to raise complaints. That’s because they don’t get any experience in medicine of clerking and managing a patient, so it’s in their interests to express their training concerns. And bear in mind this a “University teaching hospital” too. My Consultant friend was even able to raise an audit of these concerns at the tail end of a meeting with the Deanery and management staff. The management staff had no idea that they were about to be ambushed, and had presented an unblemished account. But the manoeuvre worked, as the Deanery is now receiving detailed feedback from my Consultant friend. And, particularly, the junior doctors didn’t mind raising these concerns as they are mostly looking forward to leaving the Trust, as it’s felt that they’re there on a ‘merry go round’ basis.

He says the culture is insufferable. “You keep your head down. You merely survive.”

He writes e-mails to his senior clinicians, but he never receives replies. People who raise concerns are first ignored, then discredited, then attacked, and starved of any mechanism for career progression. He says the management is ‘totally uninterested’ in his views on clinical quality control. He describes a ‘really horrible’ culture of exclusion if you voice any concerns. He says nothing can disrupt the script between the clinical leadership and the management, of how to paint the performance of the Trust in public.

He says the whole Emergency Room is set up wrong, as it has too few beds, and there’s no choice but to shunt patients to any ward within four hours. He explains a team of mainly Emergency Room (ER) doctors see the patient. Towards the end of the four hour window, a Specialist Registrar will do a minimalistic thirty minute clerking, only to be followed by a brief assessment by ER Consultant as a ‘sign off’. When the patient is received by him on a medical ward, often the basic admission investigations like bloods and chest x-ray haven’t even been done. He says he often deletes inappropriate medications off drug charts, and orders outstanding investigations. But he feels exasperated at firefighting.

He feels the complaints procedure in his Trust is virtually non-existent. Whilst patients receive a ‘welcome pack’ from the nursing staff about how to make a complaint, the staff actively do not explain to patients how they can complain about this care. This I think is a complete anethema compared to the solicitors’ regulatory code where solicitors should explain the complaints procedure on their first meeting. He says complaints are never actioned upon anyway. There’s no critical feedback loop from primary care to hospital care, or vice versa. He finally adds that the Friends and Families Test is not going anywhere in his Trust, as patients aren’t told when they receive bad care at all. If anything this test is being used by management to promote how excellent the Trust is, as management benefits from such positive reporting.

He says he’s had incomprehensible messages appearing to come from management how his discharge letters should use preferred terms such as “urosepsis” to “UTI”, or “NSTEMI” to “acute coronary syndrome”; and nobody can work out why apart from how his FT gets paid. As to what to do next, he freely admits having drawn blanks with his own NHS FT’s management and clinical ‘leaders’. He’s reported it so far to the Medical Protection Society, so I suppose he’s waiting to hear what happens. He feels that the BMA are utterly irrelevant to his concerns. He knows that the mandate for an external review from the Royal College of Physicians can only come from management. And unsurprisingly they haven’t asked for an external review. So he intends to by-pass management, being completely at the end of his tether, by asking the College directly. This reckons is a fatal flaw in the system, but one which is easily remediable.

I asked him why he hadn’t gone to the press. I thought he’d come up with the usual Doctor-patient relationship, but surprisingly he explained he hadn’t deliberately just in case it would give the Trust’s management to ‘cover their tracks’. He did look genuinely upset at this thought. He’s been invited to become an Inspector for the Care Quality Commission. He feels this is the only way now to voice his concerns.

But most of all he blames other Consultants for Mid Staffs. He feels it was up to the Consultants ‘to say something about it‘. Those who did were victimised. Those who didn’t survived. He says he can’t put up with the situation any longer because patient safety is being compromised simply so the management can ‘look good’. He feels quite paradoxically that ‘competition’ has resulted in this mess: competition amongst health professionals not to whistleblow, and competition amongst hospital managers who don’t give a toss for patient quality of care as long their national rankings for key metrics are good.

And he feels that his personal situation is not unrepresentative. This, above all, is the thing that I find the most scary.

Are integrated care packages like M&Ms? Expect a competition law armageddon.

Somewhere along the path of the subconscious of this current Government they realised competition law, as the trojan horse for implementing the private market of the NHS, would be the ‘nuclear option’ gone too far.

After the original set of section 75 NHS regulations had been humiliatingly scrapped, Norman Lamb and other LibDem members in the Upper and Lower House had to ferret around for another way to sell this discredited policy. They found ‘integration’.

The idea of co-ordinated care bundles, delivering outcomes across a range of different domains, seems like an attractive one. For the privateers, their uncanny similarity to the Kaiser Permanente Integrated Care Plan is of course enticing.

Thrust on this that private providers can cobble together au “uber contract”, subcontracting bits of it to various bods, through the ‘prime contractor model’ – and job done.

However, this way of integrating services is a ‘red rag’ to the bull of the competition authorities both here and across the pond.

You have to have been living on the Planet Mars to escape the screw-ups of the regulation of the energy market in the UK.

In 2008, the Telegraph reported the following:

Regulator tells Treasury it has found no evidence that energy companies colluded to increase bills…

Energy watchdog Ofgem has dismissed suggestions that the UK’s six largest energy companies colluded to increase gas and electricity bills. The regulator has also demanded that those alleging price-fixing should produce the evidence.

Alistair Darling, the Chancellor, summoned Ofgem chairman Sir John Mogg and chief executive Alistair Buchanan after Npower, owned by the German giant RWE, last week increased gas prices by 17pc and electricity prices by 13pc.

Mr Buchanan said yesterday: “We have no evidence of anti-competitive behaviour. We see companies gaining and losing significant market share, record switching levels and innovative deals.”

That was unbelievably five years ago.

It was once famously said that, “Integration…is like M&Ms…a thin, sugary veneer of medical ‘science’ over a yummy core of price fixing…” (US Healthcare Executive).

In the US, health care providers are generally converge upon the view that competition concerns – namely the fear of violating competition law – have had a significant chilling effect on progress toward increased integration in the delivery of health care. This, it is claimed, has led to relative ‘conservatism’ over formal partnerships.

What happens in the UK depends on how ‘light touch’ Monitor ends to be – or whether it will be relatively supine. It is still claimed by some that the light touch regulation of the City, originally introduced by the Margaret Thatcher Conservative government, led to the City spiralling out of control.

Cartels are when companies act together to behave in a way together at the expense of the customer.

Quite irrespective of their clandestine character, cartels are difficult to prove due to their varying characteristics. Cartels can be evidentially complex in the sense that the duration and intensity of participation and the subsequent anti-competitive conduct on the market may vary and take different forms.

These specificities impose a near unbearable threshold for competition authorities to prove in detail an infringement, let aside to impose an appropriate sanction reflecting the cartelists’ real participation.

Montesquieu, in his seminal work ‘De l’esprit des lois’ observed that ‘natural equity demands that the degree of proof should be proportionable to the greatness of the accusation’. While the ‘greatness of the accusation’ in cartel infringements is undisputed – especially in light of the magnitude the incurred sanctions – it appears less clear to what extent this should affect the ‘degree of proof’ of those infringements, especially having regard to their specificities.

Article 101(1) TFEU sets out the European competition law position:

The following shall be prohibited as incompatible with the internal market all agreements between undertakings, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices which may affect trade between Member States and which have as their object or effect the prevention, restriction or distortion of competition within the internal market, and in particular those which:

(a) directly or indirectly fix purchase or selling prices or any other trading conditions;

(b) limit or control production, markets, technical development, or investment;

(c) share markets or sources of supply;

(d) apply dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions with other trading parties, thereby placing them at a competitive disadvantage;

(e) make the conclusion of contracts subject to acceptance by the other parties of supplementary obligations which, by their nature or according to commercial usage, have no connection with the subject of such contracts.

In a famous case called Bayer v Commission, the Court of the First Instance, for the first time ventured to define the term ‘agreement’ as a concept that ‘centres around the existence of a concurrence of wills between at least two parties, the form in which it is manifested being unimportant so long as it constitutes the faithful expression of the parties’ intention’.

Over two centuries ago, Adam Smith, the dean of free market economics, warned: “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but tbe conversa- tion ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivanee to raise prices.” ‘^

The costs of violating price-fixing laws are very high: lawyers’ fees, government fines, poor morale, damaged public image, civil suits, and now prison terms.

While the appearance of price collusion or price fixing may seem bad in the energy market, and unproven, what will happen behind ‘closed doors’ for procedures outsourced in the NHS is likely to be a hidden scandal.

There is some truth in making the energy market more ‘competitive’. One, often rarely discussed solution, way is to ‘differentiate the product’, such that they are not all selling the same thing.

For such a homogeneous item such as gas, it is difficult to propose to do this.

Differentiating hernia operations, the bread-and-butter of the cherrypicked NHS for ‘high volume, low cost procedures’, is easier. You can vary the quality of en-suite ‘refreshments’. It’s well known that cinemas attract clients not on the basis of the quality of films, but on their range of things to go with their popcorn.

It may be intrinsically more easy to distinguish different ‘integrated care packages’, by varying the relative proportions of physical healthcare, social care, and social care (the components of what Andy Burnham MP might call “whole person care”).

The “we’ve been doing it for years” phenomenon of collusive practices is a tougher nut to crack. But in some fairness, the new private health providers haven’t been “doing it for years”, as the jet engines for the Health and Social Care Act (2012) for competitive tendering – the section 75 regulations – have only just been legislated for.

Amazingly enough, some producers of ‘folding boxes’ were given hefty fines in the United States in the 1970s. The experience there was that executives in the convicted paper companies acknowledge that the lack of contact between them and company lawyers made it hard to apply the law.

Direct contact between operating managers and members of the legal staff seemed to be less frequent in the companies that were more heavily involved in the conspiracy.

As they say, we live in ‘interesting times’, but, helpfully on this occasion, the experience from other jurisdictions may be quite helpful. Don’t blame me – Le Grand and Propper started it!

Will looking for blame in the ‘prime contractor model’ end up like one giant “pass-the-parcel”?

In a previous article of mine, “Outsourcing has become a policy drug, and they need to kick the habit”, I explained how the aspiration to have a smaller State had led to “reform” of the public services where the situation was now far worse.

Public money is being siphoned off into private sector shareholder dividends. Worse still, some performance monitoring of ongoing contracts is terrible. Furthermore, many outsourcing companies are currently embroiled in criminal allegations of one sort of another, mainly fraud.

It does seem a laudable aim to integrate healhcare (including mental health care) and social care. Indeed, by calling it ‘whole person care’, you temporarily get round the comparison to the ‘integrated shared care plans” of the United Staes.

The Health and Social Care Bill initially started life as the tr0jan horse of competitive markets into the NHS. Once this approach under Earl Howe blatantly fell apart, Norman Lamb was left to bring up the policy rear by talking about “integrated care”. However, the problem with integrated care is that it is yet again being launched as a launchpad for private providers to rustle together huge packages across a number of different areas through subcontracting.

Of course, one can argue that it’s great that a private provider can take control of so many different diverse services. But remember when the same argument was used to attack the NHS as ‘outdated’, ‘bloated’ and ‘Stalinist’? Such arguments for economies of scale or promotion of a coherent national health policy were jettisoned in favour of a fetish for introducing the market into the NHS at high speed. Unfortunately this policy has been totally discredited.

On the “prime contractor model”, the eminent health commentator Roy Lilley remarks:

Is this novel contacting or dumping the problem on someone else. Imaging trying to unpick a problem in the pathway. Everyone will blame someone else. This is a giant game of pass the parcel, isn’t it? The prime contractor may be accountable but they will pass the accountability up the line, delays will occur in getting answers. They will become a CCG-lite.

The prime contractor model involves a single organisation subcontracting work to other providers to integrate services across a pathway. A proportion of payments is dependent on the achievement of specific outcomes. Dozens of clinical commissioning groups are already said to be devising “innovative” contracts in which a lead provider receives an outcomes based payment to integrate an entire care pathway. For example, if the £120m deal is finalised, Circle ? which also runs Hinchingbrooke Health Care Trust ? will be financially and clinically accountable to commissioners for the whole pathway. The CCG said this previously involved 20 contracts across primary, secondary and community services. That news came after Bedfordshire CCG was named private company Circle as its preferred bidder to be “prime contractor” for an integrated musculoskeletal service.

Outsourcing companies don’t particularly appear to care what sectors they operate in, whether it’s in the running of healthcare, asylum seeking or probation services. Such an approach therefore lends itself easily to each citizen becoming a number not a name. The idea of us all having a special ‘services mastercard’ is not that far-fetched now, and if one day NHS budgeting is linked up with benefits, we’ll be yet closer to this ‘brave new world’.

In March 2012, G4S won a massive £30 million UK Border Agency contract to house asylum-seekers in the Midlands, the East of England, the North East, Yorkshire and Humberside. Using the “prime contractor model”, which G4S tells investors is “attractive”, the company granted subcontracts to UPM and the charity Migrant Help. And yet, in July 2013, Stephen Small, G4S managing director for Immigration and Borders, and Jeremy Stafford, Serco CEO for the UK and Europe were forced to defend their record before the Home Affairs Committee into the asylum system.

Serco’s evidence to the Committee revealed that in the North West it directly manages homes for asylum seekers through what the chair Keith Vaz described as ‘around twenty subcontractors from Happy Homes Ltd to First Choice Homes and Cosmopolitan Housing’.

Jeremy Stafford of Serco claimed this apparent recipe for housing management disaster was in fact a proven way of outsourcing and privatisation. It is ‘a very effective model and we do that in a number of the services we deliver’, he said.

This confidence in the ‘new delivery model’ of privatisation in the COMPASS contracts seems somewhat misplaced in the context of the JRF evidence. For it reveals that Reliance, the other security company with asylum housing contracts in London, the South West and Wales, sold on the privatised contracts after only two months to Capita and Clearel. The new provider, Clearel, did not fulfil the requirements of the contracts as tendered.

Only this week, the Serco boss quit. Four of the government’s biggest suppliers – G4S, Serco as well as rivals Capita and Atos – have been called to appear before a committee of British lawmakers next month for questioning about the outsourcing sector. Serco, which makes annual revenue of around 4.9 billion pounds, has continued to win deals in its other markets, such as a 335 million pound tie-up to run Dubai’s metro system, though it has encountered some problems abroad.

But back to G4S. There is even some reference to problems in the past on the G4s Welfare to Work website:

G4S Welfare to Work knows that most of the services needed to support workless people into meaningful, progressive employment in the UK already exist. What has been missing is an effective structure for managing and coordinating that provision.

… We are:

…

Operating a unique model for the delivery of welfare-to-work services that learns from mistakes made in previous Prime Contracting models, and builds on what works.

As I have described also in a previous article on this blog, one facet of globalisation is that it has become extremely difficult to regulate the behaviour of multinational corporations involved in healthcare.

G4s has now been ‘accused of “shocking” abuses and of losing control at one of South Africa’s most dangerous prisons‘. The South African government has temporarily taken over the running of Mangaung prison from G4S and launched an official investigation. It comes after inmates claimed they had been subjected to electric shocks and forced injections. G4S says it has seen no evidence of abuse by its employees. However, the BBC has obtained leaked footage filmed inside the high security prison, in which one can hear the click of electrified shields, and shrieking. It also shows a prisoner resisting a medication.

I have previously on this blog described the legal problems with the “prime contractor” model.

I have said before, and I will say it again. Especially since these contracts can be of such a long duration (for example, ten years), it is absolutely essential there are rigorous mechanisms for ongoing and continuous monitoring of performance. This way commissioners can spot easily and early on when providers are running into difficulties.

The English law gives a complex message on whether a private provider can still take the money and run, even if it doesn’t fulfill part of its side of the bargain in a contract.

Take for example the case of Sumpter v Hedges [1898] 1 QB 673 in the English Court of Appeal.

This was a matter where the plaintiff was contracted to erect certain buildings on the grounds of the defendant for a lump sum of 565 pounds, but the plaintiff was only able to do part of the work to a value of 333 pounds, with the defendant subsequently completing the rest of the work. As a result, the plaintiff sued on quantum meruit (as much as he or she has earned) appealing from the judgment of the trial judge who awarded the plaintiff for the value of the materials used, but nothing in respect to the work done.

The Court of Appeal upheld the trial judge’s decision and held that the plaintiff could not recover from the defendant in respect to the work done as part of quantum meruit due to the fact that the contract was for a lump sum, and there was no evidence that an agreement for part performance was formed.

While spinners are giving themselves multiple orgasms over ‘transparency and disclosure’ in the new Jerusalem of the NHS, it appears that “the fair playing field” of private and public health providers regarding basic patient safety is a complete fiasco.

Grahame Morris MP recently reviewed the gravity situation on the influential “Our NHS” website:

While public services are being outsourced to the private sector, especially in the NHS, Freedom of Information responsibilities are not following the public pound. Private health care companies can hide behind a cloak of commercial confidentiality when barely transparent contracts are awarded.

At the start of the bidding process private providers already receive a competitive advantage due to unequal disclosure requirements.

Private companies are free to use the Freedom of Information Act to gain detailed knowledge of a public sector provider, which can then be used to undercut or outbid the same public body when the contract is put out for tender.

NHS bodies must answer Freedom of Information requests relating to costs, performance and staffing. Yet a private provider has no similar duty of disclosure despite the fact they could have treated private patients for many years.

Once a contract is awarded, there is little that can be done if a private provider refuses to supply details to allow commissioning bodies to answer Freedom of Information requests. As they are not subject to Freedom of Information laws, the Information Commissioner has no power to investigate private contractors. They cannot serve notices for an investigation, and neither can they take enforcement action if a contractor destroys information or fails to comply with a request.

As a result of the decision in Sumpter and other similar decisions, the common law had subsequently recognised some exceptions to the general rule other than that performance of a contract must be exact and complete according to the terms. Furthermore, there is nothing preventing parties to a contractual relationship to vary or discharge the agreement, and can do so in a few ways.

One such way is “mutual discharge”, where both parties agree to release one another from what was agreed upon before either party has performed any of the acts promised. Another way is “release by one party”, where one party has completed their contractual promise, and agrees to release the other party from further performance of the contract.

Anyway, the “pass the parcel” analogy may not be entirely accurate.

It more be of the case that someone is holding a highly explosive bomb eight years into a ten year “prime contractor model” contract when it suddenly blows up.

And you can bet your bottom dollar that the Secretary of State for Health will definitely not be to blame.

The “NHS prime contractor model”: why the legal liability of subcontractors matters

At a time when “every penny counts”, it seems rather disgusting that thousands and millions of pounds should be diverted from frontline care (which we apparently can’t afford judging by the cuts in nursing jobs) to the commercial and corporate lawyers. Management consultants, politicians and staff in CCGs have no expertise in commercial law. Now that it turns out that commissioners could be freed to award work to a “prime contractor” over five to 10 years from 2014-15, according to the Department of Health, the issue of what happens if a subcontractor commits an offence in tort (negligence) or contract (breach of contract) is highly significant. The subcontractor’s damage could cause loss to the ultimate patient. Instead, commissioning pitches are full of inane garbage such as, “we need to do much better with much less“, when you consider that £20bn efficiency savings, aided and abetted by cuts in nursing staffing, is dwarfed by the new £80bn cost of #HS2. It is reported, for example, in the Health Services Journal, that,

At a time when “every penny counts”, it seems rather disgusting that thousands and millions of pounds should be diverted from frontline care (which we apparently can’t afford judging by the cuts in nursing jobs) to the commercial and corporate lawyers. Management consultants, politicians and staff in CCGs have no expertise in commercial law. Now that it turns out that commissioners could be freed to award work to a “prime contractor” over five to 10 years from 2014-15, according to the Department of Health, the issue of what happens if a subcontractor commits an offence in tort (negligence) or contract (breach of contract) is highly significant. The subcontractor’s damage could cause loss to the ultimate patient. Instead, commissioning pitches are full of inane garbage such as, “we need to do much better with much less“, when you consider that £20bn efficiency savings, aided and abetted by cuts in nursing staffing, is dwarfed by the new £80bn cost of #HS2. It is reported, for example, in the Health Services Journal, that,

“If the £120m deal is finalised, Circle ? which also runs Hinchingbrooke Health Care Trust ? will be financially and clinically accountable to commissioners for the whole pathway.”

but forgetting the spin (and one should really do that in the best interest of patients), this cannot be true if the subcontractors are excluded from liability under English law.

A useful starting point is the NHS Commissioning Board’s own “The NHS Standard Contract: a guide for clinical commissioners.”

This instrument defines the “prime contractor” as follows:

“Contract with prime contractor who is responsible for management and delivery of whole care pathway, with parts of care pathway subcontracted to other providers (Prime Contractor model). The prime contractor may not be the largest provider in the pathway but the role is focused on the pathway service delivery”.

However, the document perpetuates the notion of subcontractors’ accountability which the English Courts are likely to have difficulty with:

“The commissioner retains accountability for the services commissioned but is reliant on the prime contractor to hold subcontractors to account.”

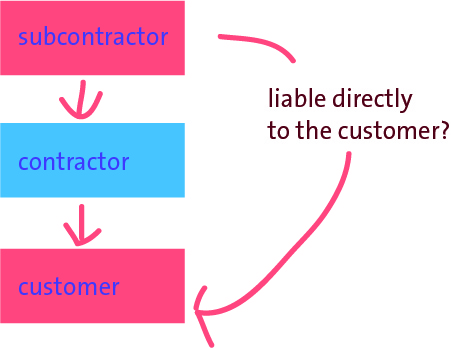

Understanding both the management principles about the safety culture in management and the legal implications of subcontracting converges on one particular industry: the construction industry. A main contractor may engage another person in order for that subcontractor to undertake a specific part of the main contractor’s works. Subcontracting is favoured in the house building industry because it offers main contractors flexibility and cost efficiencies (Ireland, 1988). However, parallels are confounded by the fact that commissioning NHS services is not the same as making buildings, the lessons from different jurisdictions are different, the degree of ‘commerciality’ of the actual contract (e.g. residential building can even be different from corporate building), the actual material facts of how close the parties are legally vary, subtle differences in the nature of contractual terms, the finding that the nature of loss may not be the same, and so it goes on. It is increasingly clear from any rudimentary analysis that the subcontractor cannot be easily accountable to the patient at all, because of a number of well settled legal principles.

A study of safety culture among subcontractors in the domestic housing construction industry using in depth semi structured interviews with 11 subcontractors from six different trades by Phil Wadick from Bellingen, Australia found that subcontractors place an enormous amount of trust in their own common sense to help inform their safety judgements and decisions (Wadick et al., 2010). According to their study, subcontractors have a deep respect and trust for the safety knowledge gained from years of practice, and a distrust of safety courses that attempt to privilege paper/procedural knowledge over practical, embedded and embodied safety knowledge.

In the law of tort, a party does not need to have a contract with another to be liable directly to that party in negligence. The legal principle of privity of contract, as stated below from Treitel, does not preclude third parties from suing contracting parties in tort.

“The doctrine of privity of contract means that a contract, as a general rule, confer rights or impose impositions arising under it on any person except the parties to it.” (GH Treitel, “The Law of Contract”)

This privity of contract is the root cause of the personal tragedy depicted in this video from the US jurisdiction, of Wendell Potter and Nataline Sarkisian: there is no direct contract between insurer and insuree.

You can see the smoking gun all too easy for this jurisdiction, where the CCGs are state insurance schemes. In England, there’s no contract between patient and provider, but only between provider and CCG and (implicitly) between CCG and NHS England. As stated correctly by Nicholas Gould, a Partner in Fenwick Ellott (the largest construction and energy law firm in the UK), there is no direct contractual link between the employer and the subcontractor by virtue of the main contract for the construction scenario. In other words, the main contractor is not the agent of the employer and conversely the employer’s rights and obligations are in respect of the main contractor only. The employer therefore cannot sue the subcontractor in the event that the subcontractor’s work is defective, is lacking in quality, or delays the works. The subcontractor situation therefore merits some particular scrutiny in the law of tort, where it is necessary to establish a breach of a duty of care, with sufficient cauality, to prove negligence on the balance of probabilities.

Typically, in their contracts, the “prime contractor” will limit its liability to a customer to a patient ultimately, and in turn the subcontractor will limit its liability to the prime contractor. In the 2004 case of Rolls-Royce New Zealand Ltd v Carter Holt Harvey Ltd [2004] NZCA 97; [2005] 1 NZLR 324 (23 June 2004) “Rolls Royce”, the Court of Appeal of New Zealand decided that the subcontractor in that construction case could not be liable to the customer. In Rolls Royce, the Court of Appeal said that whether or not a duty of care should be recognised in New Zealand depended on whether, in all the circumstances, it was just and reasonable that such a duty is imposed. This, in turn, involves two broad fields of inquiry. First is the degree of proximity or relationship between the parties, and second is whether there are any wider policy considerations that might negate or restrict or strengthen the existence of a duty in any particular class of case.

But can a duty-of-care by the subcontractor be held in tort in the English law? The House of Lords attempted to establish a general duty of care in respect of pure economic loss resulting from a negligent act, based on the closeness of the relationship between the parties and reliance by the claimants on the defendants’ skill and experience, in Junior Books Ltd v Veitchi Co Ltd [1982] UKHL 4 (15 July 1982). This Scottish case represents the high water mark for liability in tort for subcontractors to employers in respect of negligence. In this case a contractor was engaged to construct a factory for the building owner. The defendant subcontractors were engaged to lay a specialist composite floor. The floor was defective and began to crack almost immediately. However, there was no danger to the health and safety of the occupants, nor any danger to other property of the building owner. Regardless, the floor needed replacement because of the defects. There was no direct contract between the employer and the subcontractor, but the building owner sought the costs of replacement and loss of profit while the flooring was being relayed from the subcontractor, and succeeded in the House of Lords. Lord Keith of Kinkel advised about the need to avoid extrapolating too widely from the ratio of this case:

But can a duty-of-care by the subcontractor be held in tort in the English law? The House of Lords attempted to establish a general duty of care in respect of pure economic loss resulting from a negligent act, based on the closeness of the relationship between the parties and reliance by the claimants on the defendants’ skill and experience, in Junior Books Ltd v Veitchi Co Ltd [1982] UKHL 4 (15 July 1982). This Scottish case represents the high water mark for liability in tort for subcontractors to employers in respect of negligence. In this case a contractor was engaged to construct a factory for the building owner. The defendant subcontractors were engaged to lay a specialist composite floor. The floor was defective and began to crack almost immediately. However, there was no danger to the health and safety of the occupants, nor any danger to other property of the building owner. Regardless, the floor needed replacement because of the defects. There was no direct contract between the employer and the subcontractor, but the building owner sought the costs of replacement and loss of profit while the flooring was being relayed from the subcontractor, and succeeded in the House of Lords. Lord Keith of Kinkel advised about the need to avoid extrapolating too widely from the ratio of this case:

“Having thus reached a conclusion in favour of the respondents upon the somewhat narrow ground which I have indicated. I do not consider this to be an appropriate case for seeking to advance the frontiers of the law of negligence upon the lines favoured by certain of your Lordships. There are a number of reasons why such an extension would, in my view, be wrong in principle.”

The courts began, however, to retreat from the implications of Junior Books almost immediately. The leading speech was given by Lord Roskill and he based his analysis on Lord Wilberforce’s infamous two stage test for establishing a duty of care set out in Anns v Merton London Borough Council [1977] UKHL 4 (12 May). This approach was of course overruled in Murphy v Brentwood District Council [1990] UKHL 2 (26 July). In Southern Water Authority v Carey [1985] 2 All ER 1077, the work was defective and the entire sewerage scheme failed. The Authority sued the subcontractor in negligence, and yet the High Court decided that the subcontractor was not liable in tort as a result of the terms of the main contract.

Nonetheless, there are a variety of general principles applicable to subcontractor relationships. First, the main contractor remains responsible to the employer for a number of diverse aspects of the subcontract. In other words, the main contractor is still responsible for time, quality and paying the subcontractor in accordance with the contract between the main contractor and subcontractor regardless of any issue that could arise between the main contractor and the employer. This will of course depend upon the terms of the contract between the main contractor and a subcontractor, and might also depend on the separate contract between the employer and main-contractor. However, they are nonetheless two separate contracts, and the legal doctrine of privity of contract applies in this jurisdiction as in many jurisdictions for the “prime contractor model”, and the matching or integration of similar “back to back” obligations is often unsatisfactory. Clever drafting can even lead to the subcontractors escaping liability altogether. For example, quite recently, it is reported that a dredging subcontractor, Van Oord, escaped liability for the design of dredging works due to the exclusion clause in its tender (Mouchel Ltd. v Van Oord (UK) Ltd., [2011] EWHC 72).

With all this uncertainty, it is quite unhelpful that there is also much uncertainty about how a subcontractor will have been deemed to have ‘failed': the so-called “outcomes-based commissioning“. It could be that there could also be patient feedback indicators built into the deal, which commissioners hope will enable them to hold the lead provider to account if people’s experience of services suffers. “Soft intelligence” from GPs could also be used. The legal cases will certainly turn on their own material facts, but, with a time window which could be as large as 10-15 years and with fairly strong private providers financially (important for business continuity), it is likely that the English law courts will be asked at some stage to decide upon whether the subcontractor can be legally ‘accountable’ to the patient. The answer is very likely to be “no”, and there will be then many very angry intelligent people who will feel that they simply have been misled. A lot of liability rests with the CCG accountable officer position – but if all goes wrong such officers can simply move onto other well-paid jobs in other sectors. When you consider the death of legal aid for clinical negligence, some might say this a real mess.

Not to worry – it’s business as usual.

Further reading

Ireland, V. (1988), Improving Work Practices in the Australian Building Industry. A Comparison with the UK and USA, Master Builders Federation of Australia.

Wadick, P (2010), Safety culture among subcontractors in the domestic housing construction industry, Structural SurveyVol. 28 No. 2, pp. 108-120

What the Lewisham decision is about, and, more importantly, what it isn’t about

R (on the application of LB of Lewisham and others) v Secretary of State for Health and the TSA for South London Hospitals NHS Trust High Court of Justice (Queen’s Bench Division) Administrative Court [2013] EWHC 2329 (Admin)

Judgment here

None of this of course was ever meant to happen (except it was, because the history is elegantly deciphered in “NHS SOS”, edited by Tallis and Davis). Remember this?

The Lewisham decision was taken relating to a specific legal problem, in a particular place at a particular time. Judge Silber therefore applied the law to that particular situation, and he specifically did not wish to go into the merits of the case. He just looked at how the decision was taken, which was a bad mess. Jeremy Hunt, the Secretary of State for Health, either received bad legal advice, or chose to ignore the legal advice he was given. There are useful lessons to be learnt from the judgment (“Judgment”) though, which is a beautiful piece of work. Certain issues were avoided altogether, such as how next to proceed (is there a need for a reconsultation? who should now make the decision? The Judgment does not discuss whether neoliberal economics produces the best outcome for patients in the National Health Service, nor does it opine on the eventual consequences of failure regimes around the country. It takes the case law further, but the danger is that too much can be read into its significance. However, in terms of morale and confidence, this was undoubtedly a much needed ‘boost’ for the patients, public and clinicians of Lewisham.

At the root of the problem, the Prime Minister had said:-

“What the Government and I specifically promised was that there should be no closures or reorganisations unless they had support from the GP commissioners, unless there was proper public and patient engagement and unless there was an evidence base. Let me be absolutely clear: unlike under the last Government when these closures and changes were imposed in a top-down way, if they do not meet those criteria, they will not happen.”

The draftsman of the parliamentary legislation is aware of the problem posed by the Secretary of State having a duty to provide a comprehensive NHS. This is, of course, the major faultline in English health policy, with both the Conservatives and Labour truly adamant about ‘comprehensive, free-at-the-point of use, universal’, while stories appear all the time – in a drip-drip fashion – about the manifestations of rationing. Again, Silber can only refer to the law as it was at the time in para. 61:

61 All these matters have to be considered against the background that under Section 1 of the 2006 Act, the Secretary of State has the duty of continuing the promotion in England of a comprehensive health service. Section 3 of the 2006 Act specifies the Secretary of State’s duty to provide or arrange the provision of a wide range of services (including hospital accommodation and services) to such extent as he considers necessary to meet all reasonable requirements. Section 2 gives the Secretary of State the power to provide other services as he considers appropriate for the purpose of discharging any duties conferred on him by the 2006 Act.

Against this is the backdrop that each NHS Trust is a separate financial and clinical entity, allowing for units to be ‘ringfenced’ as or when they run into financial or clinical problems. The problem has emerged where the parliamentary draftsman has found himself producing every voluminous legislation to cover any eventual possibility, which is why Silber is able to state confidently as a point of legal fact at para. 76:

76 It is clear that each NHS Trust is a separate entity, and this issue raises questions of statutory interpretation.

The tension in reconciling the needs of the entire National Health Service and local resource of allocation, of course, had to be addressed, and indeed it was. What is certain is the extent to which national policy will be sketched out for the strategic and operational management of the entire NHS, calling into question the mantra of Andy Burnham MP, “putting the ‘N’ back into NHS”.

81 Third, the Parliamentary draftsman chose to distinguish between “the interests of the Health Service” and those of the Trust.

What clearly emerged yesterday was that any-old promise does not produce a ‘legitimate expectation’ in this jurisdiction. This of course will also be great news for Nick Clegg after his tuition fees fiasco. Indeed, in my blogpost of July 7th 2013 for the “Socialist Health Association”, I wrote the following:

“And what about the actual law? R v. Inland Revenue Commissioners ex parte MFK Underwriting Agents Limited (1991) WLR 1545 in which Bingham LJ and Judge J stated that, for a statement to give rise to a legitimate expectation, it must be:

“clear, unambiguous and devoid of relevant qualification” (para. 1570)

The promise has to be made by the decision maker: R (on the application of Bloggs) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2003] EWCA Civ 686, [2003] 1 WLR 2724. Further the promise must be made by someone with actual, or ostensible, authority, otherwise the decision will be ultra vires: South Buckinghamshire DC v Flanaghan [2002] EWCA Civ 690, [2002] 1 WLR 2601. The promise has to be made by the decision maker: R (on the application of Bloggs) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2003] EWCA Civ 686, [2003] 1 WLR 2724. Further the promise must be made by someone with actual, or ostensible, authority, otherwise the decision will be ultra vires:South Buckinghamshire DC v Flanaghan [2002] EWCA Civ 690, [2002] 1 WLR 2601.”

Justice Silber felt, like me, that there could be no legitimate expectation:

99. In this case, the Secretary of State was merely saying that he intended to rely on the Chapter 5A regime which is a rapid decision-making process in which services can be properly configured, but only provided that certain requirements were met. Indeed in his statement, the Secretary of State was saying nothing more than that he proposed to rely on the statutory regime which included certain requirements to consult. This was uncontroversial and does not alter what the Secretary of State was obliged to do.

100. In my view, the Minister’s statement relied on by the Campaign cannot give rise to a legitimate expectation because as a matter of general principle the undertaking or promise which gives rise to the alleged legitimate expectation must be, in the words of Bingham LJ, “clear, unambiguous and devoid of relevant qualification” (R v Inland Revenue Commissions, ex parte MFK Underwriting Agencies Limited [1991] WLR 1545 at 1569).

Having said there was no ‘legitimate expectation’, I felt it was quite generous of Silber nonetheless to consider the ‘promise’ in para 112:

112. The four reconfiguration requirements were designed for local service reconfigurations and not for decisions under Chapter 5A of the 2006 Act, which is, as I have explained, an expedited and emergency procedure. Paragraph 39 of the Statutory Guidance states that:-

“In assisting the Secretary of State to make a final decision on the future of the organisation, [the TSA] should have regard to the Secretary of State’s four key tests for service change in developing his or her recommendations i.e. local reconfiguration plans must demonstrate support from GP commissioners, strengthened public and patient engagement, clarity on the clinical evidence base and support for patient choice.”. (Emphasis added)

And all of this is a legacy of the Lansley bygone era. Lansley’s “promise” may have been politically expedient at the time, but clearly had not escaped the attention of Silber:

109. In an article in the Daily Telegraph on the following day, Mr Andrew Lansley, M.P., who was then the Secretary of State, explained the new principles stating that they “will not merely be another tick-box exercise – it will be a tough test which every proposal must pass if it is to succeed”.

It had even been sufficient for Sir David Nicholson to confirm this:

123 The Claimants point out that after his initial letter of 20 May 2010, Sir David Nicholson wrote again to all NHS Chief Executives on 29 July 2010 referring again to these four new requirements explaining that “the Secretary of State has also made it clear that GP Commissioners will lead local changes in the future”.

124. The letter also attached a document entitled “Applying the Reconfiguration Test”. Under the heading entitled “Support from GP Commissioners”, the process is defined in this way and with emphasis added:-

“Local commissioners and consortia should review the current evidence of engagement with GPs and the level of support and consensus for a proposed service change. As GP/practice based commissioning structures vary across the country, local commissioners will need to take an appropriate view as to how best to gather this evidence, with PCTs supporting this process where required. Commissioners will need to consider the engagement that may need to take place with practices whose patients will be significantly affected by the case for change, inviting views and facilitating a full dialogue were necessary”.

Where the Judgment really comes into its own is at this point. It first of all accepts that the consultation which took place, in terms of patient engagement, “worked”:

141 The engagement with patients and the public also occurred through patient and public advisory groups as well as in individual meetings with representatives of many local involvement networks and focus groups. There was also formal consultation on the draft recommendation with 27,000 full consultation documents and 10,000 summary documents distributed through 2000 locations across South East London.

However, the judicial consideration of the extent to which ‘patient choice’ matters is clearly set out in para. 166. While this might seem like a rather terse exercise in statutory interpretation, it is obviously significant as to whether any one group of patients, however articulate, can ‘veto’ a progress of policy. This wider nuanced interpretation is very helpful, in that it allows clinicians also to have their say about patient issues legitimately:

166. Mr Phillips submits correctly that this requirement to be “consistent with” in this requirement cannot and does not mean “the same as”. The Secretary of State was quite entitled to accept the view that concentrating clinical sites to drive up clinical quality so that although it inevitably reduces patient’s choice, it still increases choice between high quality services.

There are discussions to be had about whether CCGs will be impressed about the ‘snake oil’ nature of ‘more for less’ (which is rapidly becoming ‘less for less’, or even ‘less for more’, as some NHS budgets become subsumed in paying off high-interest loans for PFI arrangements). The ‘more for less’ philosophy is of course pervasive in the pitches for CCGs in the philosophy of making existant staff ‘working more effectively’ or working ‘more imaginatively’. Whilst integrated teams, downsizing clinical specialisms, may appear to save money to make Nicholson savings work, coupled with unsafe doctor:bed or nursing:bed ratios, a highly toxic mix of ‘front door firefighting’ might emerge, leaving only HSMRs much later down the line to pick up any damage done possibly. Of course, the platitude that it can all be done in the community might sound nice, but it is not so much if the decisions of Consultants leads to quick-fix TIA management leading to full-blown haemorrhagic strokes. This of course is a personal tragedy for the patient, as well as a hole in the budget for NHS managers. Nor indeed, a quick-fix unstable angina management leading to a full-blown coronary artery bypass graft. The NHS will remain crippled with the implementation of a “jam tomorrow” philosophy, but there are lots of clever salesmen out there to pull the wool over the eyes of vulnerable people.

However, the Lewisham result is monumental. It restores faith in the idea that the views of clinicians, public and the patients matter. It is hugely important that the judiciary should say to the legislature that the Secretary of State acted outside the law – he actually UNLAWFULLY. It restores faith in the idea that somebody will listen to it all fairly. It restores faith in the idea that nobody is above the law. Whilst the focus of the Lewisham judgment was focused on Lewisham policy issues, there are, as argued above, huge implications for the rest of English health policy, and, crucially, the manner and style in which it is conducted. Lack of even ‘shotgun diplomacy’ is no longer an option. Certain people, especially Jeremy Hunt, will have to tread very carefully. Finally, I should like to pay a personal tribute a huge army of people involved in this. It would be unfair to single out particular individuals, but please do allow me to say thank you to @jos21, @carolmbrown, @drmarielouise, @lewishamcouncil, @goonerjanet, @savelewishamAE, @snigskitchen and @drjackydavis (list not to be read “expressio unius est exclusio alterius” as the lawyers say.)

The “Friends and Family Test” – lessons from the “Do you masturbate often?” question

In whatever way you wish to ask the question from an expert statistician, a reasonable statistician will spit bullets at the methodology of “The Friends and Family Test”. Like Trip Advisor, it is susceptible to a phenomenon called ‘shilling’, where fake respondents bias the sample with their fake appraisals. The Friends and Family Test (FFT) is a single question survey which asks patients whether they would recommend the NHS service they have received to friends and family who need similar treatment or care. Conceptually, it is of course a terrific idea to ask the patient what they think of the NHS, but it is susceptible to too many uncontrolled variables for the result to be particularly meaningful; for example, how long after the clinical event should you ask the patient to ‘rate’ the episode? The responses to the FFT question are used to produce a score that can be aggregated to ward, site, specialty and trust level. The scores can also be aggregated to national level.

Most people in the public are very slightly interested in the geeky way in which statisticians produce the results, The scores are calculated by analysing responses and categorising them into promoters, detractors and neutral responses. The proportion of responses that are promoters and the proportion that are detractors are calculated and the proportion of detractors is then subtracted from the proportion of promoters to provide an overall ‘net promoter’ score. NHS England has not prescribed a specific method of collection and decisions on how to collect data have been taken locally. Each trust has been able to choose a data collection method that works best for its staff and people who use services. The guidance suggests a range of methods that can be adopted including tablet devices, paper based questionnaires and sms/text messages, amongst others. How you collect the data adds a further level of complexity to the meaningless nature of these data.

There is a phenomenon in statistics called the “social desirability responding” (“SDR”), a tendency of respondents to answer questions in a manner that will be viewed favorably by others. It can take the form of over-reporting “good behaviour” or under-reporting “bad,” or undesirable behaviour. The tendency poses a serious problem with conducting research with self-reports, especially questionnaires. This bias interferes with the interpretation of average tendencies as well as individual differences. There might be an age-related effect; older patients have tended to hold the NHS with greater reverence, whatever their political loyalties might be, compared to younger patients who believe in a market and/or believe they are ‘entitled’ to the NHS.

Topics where socially desirable responding (SDR) is of special concern are self-reports of abilities, personality, sexual behaviour, and drug use. When confronted with the question “How often do you masturbate?”, for example, respondents may be pressured by the societal taboo against masturbation, and either under-report the frequency or avoid answering the question. Therefore the mean rates of masturbation derived from self-report surveys are likely to be severe underestimates. Social desirability bias tends to be highest for telephone surveys and lowest for web surveys. This makes web surveys particularly well suited for studies of sexual behaviour, illicit activities, bigotry, or particularly threatening topics. Fundamentally, respondents do not answer questions the same way in person, on the phone, on paper or via the web. Different survey modes produce different results. Robert Groves, in his 1989 book “Survey Errors and Survey Costs“, argues that each survey mode puts respondent into a different frame of mind (a mental “script”). Face-to-face surveys prompt a “guest” script. Respondents are more likely to treat face-to-face interviewers graciously and hospitably, leading them to be more agreeable. Phone interviews prompt a “solicitor” script. Respondents are more likely to treat phone interviews the way they treat calls from telemarketers, making them more likely to go through the motions of answering questions in order to get the interviewer off the phone.

That is why reasonable statisticians take care when comparing the results of surveys conducted by different modes. Humans process language differently when reading, when listening to someone over the phone, or when listening to someone in the same room (when visual cues and body language kick in). It is no surprise that these different modes lead to different behavior by respondents. The lack of a standardised methodology in the FFT means that there are likely to be, what are known as, mode effects. Mode effect is a term used to describe the phenomenon of different methods of administering a survey leading to differences in the data returned. For example, we may expect to see differences in responses at a population level when comparing paper based questionnaires to tablet devices. On a positive note, mode effects do not prevent trusts from comparing their own data over time periods when they have conducted the test in the same way, as any biases inherent in the individual approaches are constant over the period.

Much money has been pumped into the FFT, and one wonders whether the FFT would stop another Harold Shipman or Mid Staffs. Even Trusts with excellent ratings, such as Lewisham, are in the “firing line” for being shut down. So one really is left wondering what on earth is the point of flogging this dead policy horse?

Compromise agreements, redundancy and efficiency – the ingredients of a ‘perfect storm’ in the NHS?

The NHS spent £15 million in three years on gagging whistleblowers, according to the Daily Mail. In just three years there were 598 ‘special severance payments’, almost all of which carried draconian confidentiality clauses aimed at silencing whistleblowers. They cost the taxpayer £14.7million, the equivalent of almost 750 nurses’ salaries.

Whistleblowers have found them at the end of such agreements, and why the NHS culture is not one of transparency and trust is a damning observation. Compromise agreements have also been used in ‘genuine’ situations of redundancy. Redundancy arises when an employer either:

- Closes the place of work; or

- Reduces the number of employees which are employed by it.

The employer is under an obligation to pay a redundancy award to any employee who is dismissed by reason of redundancy if that employee has two years’ service or more. From an employee’s perspective, it is quite common that when employment ends, you and your employer agree to enter into a “Compromise Agreement”. The purpose of the compromise agreement is to regulate matters arising from the termination. A compromise agreement is a legal document that records the agreement between an employee and employer whereby the employee agrees to ‘compromise’, or not to bring, a claim against the employer in relation to any contractual or statutory claims they may have in relation to their employment or the manner of its termination. This type of agreement is typically in return for the payment of a sum of money from the employer to the employee. It may also contain details of additional ancillary agreements between the parties on topics such as: ongoing confidentiality/ restrictions, agreed form references etc.

Compromise Agreements can be very effective and, in essence, amount to a ‘clean break’ that, hopefully, benefit both parties and enable everyone to move on. They are enshrined in law through s.203 Employment Rights Act (1996). A dismissal by reason of redundancy can amount to an unfair dismissal. There are other statutory reasons for unfair dismissal which are allowed, which are cited earlier in the Employment Rights Act.

A dismissal by reason of redundancy can amount to an unfair dismissal. Issues which render such dismissal unfair often include:-

- The selection of a pool of employees from which the redundant candidate is chosen;

- The criteria for such selection; and

- Failure to consult appropriately.

The House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts published a document “Department of Health: progress in making NHS efficiency savings: Thirty-ninth Report of Session 2012–13″ on 13 March 2013. The discussion between Meg Hillier and Mike Farrar talks about redundancy payments, but interestingly this document does not refer to ‘compromise agreements’ once.

“Q29 Meg Hillier: Maybe at chief executive level, but I know for a fact that there are people out there who have taken generous redundancy payments—they may genuinely have thought they were not going to work in the NHS again—but there is such demand for their skills and services that they have been brought back in. There seems to be no real ability to have safeguards. I know they are your members, so maybe it is in your interests for them to get these positions, but this is about all taxpayers’ money, and in the end it affects everyone.

Mike Farrar: We have tried to support the management of people through the system to the best possible place to get the best value for taxpayers; that is what we would want to see. The reforms have abolished authorities and organisations. People have not been able to take redundancy unless they were eligible for redundancy on the basis that their organisation has been abolished. That has allowed management cost savings of a significant level—

Q30 Chair: Well, we do not know, because you might have had a whole load of management costs in terms of redundancy, with people then re-emerging elsewhere. We are very sceptical.

Mike Farrar: I think the reforms of this House are responsible for certain people having been eligible for redundancy. There is a notion that those individuals leapt at the chance to be made redundant in order to deploy their services back, but that has only been created in terms of an opportunity because of reforms passed by the House. Some of these points were made during the passage of the Bill. “

HM Government has never published its “Risk Register” for the Health and Social Care Act (2012), despite the guidance involving the Information Commissioner. Today’s Report published by the National Audit Office on the use of compromise agreements makes for depressing reading:

“There is a lack of transparency, consistency and accountability in the use of compromise agreements in the public sector and little is being done to change this situation, an investigation by the National Audit Office has found.

Public sector workers are sometimes offered a financial payment in return for terminating their employment contract and agreeing to keep the facts surrounding the payment confidential. The contract is often terminated through the use of a compromise agreement and the associated payment is referred to as a special severance payment.

The spending watchdog highlights the lack of central or coordinated controls over the use of compromise agreements. The NAO was not able to gauge accurately the prevalence of such agreements or the associated severance payments. This was down to decentralized decision-making, limited recording and the inclusion of confidentiality clauses which mean that they are not openly discussed. No individual body has shown leadership to address these issues; the Treasury believes that there is no need for central collection of this data.”

It could be there that there is a fundamental faultline in how performance management in the NHS is currently being implemented, in which commercial lawyers are not quite silent bystanders. That is, the NHS has found itself in a situation where it is generating efficiency savings, which do not get ploughed back into frontline care. A reasonable place to start is also the implementation of the Health and Social Care Act (2012), and this complex strategic restructuring has obviously had its opportunity cost, even as described on Wikipedia here:

When you have CEOs and NHS Foundation Trusts being judged by their ‘efficiency savings’ which may involve redundancies (though these parties will argue that many of these staff are mostly employed back), the performance management system is heavily weighted against long-serving staff with experience and skills of working in the NHS who ought to be cherished for ‘adding value’. This is clearly a massive fault with how the NHS rewards ‘success’ in the NHS (and if the CQC’s recent scandal and more are anything to go by does not appear to punish ‘failure’ in the regulatory system, either.) And when you add to that that the experience of NHS whistleblowers, often at the receiving end of compromise agreements with suboptimal legal advice (whereas the NHS has access to the best commercial and corporate lawyers), is that whistleblowers tend to get humiliated and marginalised to such an extent that they never work again, you can see how compromise agreements, while certainly enshrined in law for a legitimate person, along with an alleged lack of teeth of the Public Interest Disclosure Act (1998), has successfully allowed a ‘toxic culture’ to perpetuate very successfully indeed?

“Lessons learned” – If every unemployment statistic is a tragedy, what was every ‘excess death’ at Mid Staffs?

It never fails to amaze me how certain policy strands run in parallel along a disastrous course, but silos in journalism mean that you’ll never get people joining the dots.

One example of this is the competitive tendering in legal services which Chris Grayling MP is currently shoehorning through, despite overwhelming opposition from lawyers including QCs. Everytime the unemployment figures up, or we have another revival in youth employment, Chris Grayling used to be the guy on TV saying that ‘every statistic is of course a personal tragedy’. Curiously you never get this phrase said about any excess death from the NHS which happened out of the ordinary. The concept that it is impossible to measure excess deaths at all will be alien to any professional in clinical negligence, who will be able to follow through the well-worn logic of duty-of-care of a clinician, failure of that duty causing breach, and that breach causing damage provided that there is not remoteness. We all know that the media is prone to hysteria, and indeed John Prescott once advised me not to believe everything written about ‘one’ in the papers. And an issue undoubtedly is that some are using what happened at Mid Staffs for their own agendas. You’d be forgiven for thinking some reports have the sole intention of shutting down the entire NHS as a national health service, blow all its credibility to smithereens, and to prepare its purchase price for the lowest bidder in a Government which has relish in outsourcing and privatisating the State infrastructure.

However, the sensationalism which was embraced whether there were any ‘excess deaths’ or not is perhaps distasteful at best, and frankly rude at worst. Mortality ratios are supposed to be the ‘smoke alarm’, but now that the inferno has happened, it is not time to remove the batteries from the smoke detector. The public inquiries at Mid Staffs I feel were essential. I don’t feel that this is an issue which could have been discussed behind closed doors ‘in camera’. It might be feasible to hold no-one accountable as the ‘culture’ is so widespread, but that has not led professionals to escape liability ever before for fundamental breaches in care, such as poor note-keeping, unprompt investigations, poor conduct and communication, from the professional regulators. The frustration has been there appears to have been very little accountability, and this is significant whether one feels the role of the justice system should be fundamentally restorative, retributive or rehabilitative. A certain amount of hysteria has instead engulfed proceedings at Mid Staffs, with the recently reported hostile behaviour towards Julie Bailey, remarkable campaigner and founder of ‘Cure the NHS’.

However, Julie has never wanted to ‘Kill the NHS’, but is deeply hurt about what happened to her Mum. Deb Hazeldine is very hurt about what happened to her mum. Any reasonable daughter would. These are times for reports of personal tragedies. Whilst we all have to move on, it is important to acknowledge accurately the distress of what happened, and this is precisely what we achieved in the Francis Inquiries. The accounts in those Inquiries are not figments of anyone’s imagination. It is even possible that we may have to learn from what happened there for other NHS Trusts. There is a trail of logic which goes that ‘efficiency savings’ were in fact cuts which included relative staff shortages, despite more being spent on the NHS budget overall including for salaries for certain personnel; this meant that key critical frontline staff were overstretched, there were genuine clinical events in patient safety which went beyond ‘near misses’, but they were not adequately dealt with. The Francis Inquiries should not be used to draw closure on the matters for the Labour administration, which I broadly supported. The reaction to the situation, a real one of personal tragedy, should not in my view a retweet of a blog which says that standard mortality ratios are unreliable, however correct that blog might be. This for me is not in any way personal – I like and respect very much people on all sides of what has been a highly charged discussion. I have known some of them for ages, and I will continue to support them publicly and in private.

We are not at the end of the solution of what happened in Mid Staffs, and for the time-being we should honestly recognise that.

Is socialism consistent with judicial review?

The simplest answer to, ‘Is socialism consistent with judicial review?’ might be ‘Yes absolutely – it’s a very useful way to hold authorities to account’.

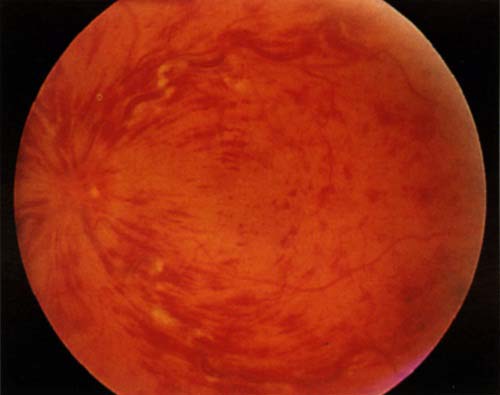

To my knowledge, “central retinal vein occlusion” is still a popular ‘spot diagnosis’ in the clinical examination for the Royal Colleges of Physicians of the UK.

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (“NICE”), as a public body with statutory powers from law, makes decisions about treatments in the NHS, and a number of its decisions have been subject to ‘judicial review’ in the past. Judicial review is a procedure in English law by which the courts in England and Wales can supervise the exercise of public power on the application of an individual. A person who feels that an exercise of such power by a government authority, such as a minister, the local council or a statutory tribunal, is unlawful, perhaps because it has violated his or her rights, may apply to the Administrative Court (a division of the High Court) for judicial review of the decision and have it set aside (quashed) and possibly obtain damages.

NICE concluded in July 2011 that dextramethasone-intravitreal implants implants, that are installed every six months and help prevent sight deterioration, and represented a cost-effective use of NHS resources. The macular is the central part of the retina responsible for colour vision and perception of fine detail. Macular oedema is where fluid collects in the retina at the macular area, which can lead to severe visual impairment. Straight lines may appear wavy, and one may have blurred central vision or sensitivity to light. However, according to a recent article in the Guardian newspaper, a survey of 125 hospital trusts in England with eye health services conducted by the Royal National Institute of Blind People in February found that of the trusts that responded, 45 were providing a full service and 37 were providing either a restricted service or no service. In his article, Sir Michael Rawlins in the Health Services Journal said he had advised the RNIB to make an application to the high court and seek a judicial review.

Socialism and judicial review, however, have not historically been natural ‘soulmates’. In EP Thompson’s “Whigs and Hunters” (1975), it is argued that judicial review (and ‘rule of law’) has been an useful way of exerting influence in capitalist ideologies, particular in the context of ‘abuse of power’. It can be argued that judicial review and ‘the rule of law’ go hand-in-hand in that the ‘rule of law’ fundamentally provides that nobody is above the law, and that the law is supreme. To that extent, everyone has an equal say, and judicial review can therefore represent the needs of underprivileged members of society. To that extent, it might be very reconcilable with socialism; sufferers of dementia might be considered some of the more disadvantaged members of society, and a decision to make cholinesterase inhibitors available for amelioration of cognitive symptoms might be a meritorious one in terms of fairness.